College of Social and Behavioral Science

156 An Analysis of Social Class Representation in America

Max Lepore

Faculty Mentor: James Curry (Political Science, University of Utah)

When we make the decision of who to vote for in elections, we may consider voting for candidates who share similarities with us. If such similarities exist, these candidates may hypothetically pursue, advocate, and vote for policies we support. In her 1999 work “Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? Contingent ‘Yes,’” Jane Mansbridge explores this concept of representation and defines it as “descriptive representation” (p. 629). Descriptive representation entails representatives who share specific characteristics with the people who they represent (Mansbridge, 1999): Black Americans representing their black constituents, women representing women, and so on. In the aggregate, this type of representation can be measured by its level of success, or in other words, how proportionally a group is descriptively represented in an elected body compared to their abundance in the electorate. However, one key element of this concept for Mansbridge is that this is not limited to purely visible characteristics like race or gender but also “shared experience,” an idea that “lies at the core of descriptive representation (p. 629). For example, farmers can descriptively represent their constituents that are farmers. Mansbridge gives a strong and digestible conceptualization of descriptive representation, and it serves as a strong theoretical framework to apply to practical situations of the representation of different groups in our country.

However, it must be recognized that descriptive representation is not always the final goal of representation as we cannot assume it will guarantee substantive representation, a term that addresses if a group’s interests are being pushed for in elected bodies (Mansbridge, 1999). How these two types of representation interact is key, and it must not be assumed a relationship between them exists for every identifiable characteristic. Rather, the presence and nature of such relationships must be investigated in differing contexts of representation.

In some situations, descriptive representation can be directly connected to substantive representation, which should be the primary goal of political representation for historically underrepresented groups because it actually focuses on policy actions and outcomes that impact people’s lives. To show how this relationship can potentially exist, Mansbridge tells the story of Carol Moseley-Braun, who was the only black U.S. senator in 1993 (Mansbridge, 1999). When a white male senator presented an amendment aiming to renew a design patent for a confederate flag, Moseley-Braun was the only legislator who took a stand. Mansbridge uses this example to show how descriptive representation can be valuable in politics. In speaking to the Senate, Moseley-Braun addressed the fact that she understood how black people in America were constantly reminded that their ancestors were treated as property (Oh, 2015). Even though this was an issue that had not been discussed during her campaign, Moseley-Braun was able to speak on behalf of her black constituents. Her “shared experience” as a black woman afforded Moseley-Braun the “sensibility” to represent her black constituents, making a difference in how she represented her constituents in the Senate (Mansbridge, 1999, 647). In fact, Moseley Braun’s objection was so important that it ended up changing the outcome of this amendment, showing that here, her descriptive representation directly resulted in substantive representation (Clymer, 1993).

However, it is not always sufficient to settle for descriptive representation on its own. In doing so, we can end up with people like George Santos, a gay former congressman from New York who criticized the parenting of same-sex couples, supported Florida’s infamous “Don’t Say Gay” bill, and partnered with far-right organizations throughout his career (Kane, 2023; Baska, 2023). His frequent attacks on the LGBTQ+ community serve as an important reminder that we should not assume descriptive representation translates into substantive representation. In looking to improve our country’s treatment of historically marginalized groups, we must analyze this relationship and determine whether descriptive representation achieves beneficial and substantive policy outcomes for specific groups.

Working-Class Representation

A significant amount of research has been conducted on this connection between descriptive and substantive representation in regard to race and gender, but one significant aspect that has not been thoroughly explored is social class (Carnes, 2013). This lack of research is problematic because while women and racial minorities have increased their congressional representation over the last century, the extreme descriptive underrepresentation of working-class individuals has not improved. These blue-collar workers, who “worked as manual laborers, service industry workers, or union officials before entering politics” made up 54% of our nation’s population at the beginning of the 21st century, but were descriptively represented at a rate of just 2% in Congress around the same time (Carnes, 2013, p. 7). This group is also severely underrepresented in local government, with recent data showing just 3% of state legislators and 9% of city council members held a working-class job prior to their election (Carnes, 2013). These great disparities led Nicholas Carnes to collect and analyze data to see if this lack of representation is consequential. In his 2013 book White-Collar Government: The Hidden Role of Class in Economic Policy Making, Carnes examines a plethora of datasets to explore the question that matters in this discipline: Does the underrepresentation of the working class in our country have a significant impact on political outcomes, and thus, the lives of everyday Americans?

Carnes measures working-class representation through occupation because occupation is a strong predictor of other measures of social class, such as income (Carnes, 2012). In this way, he argues that occupation is a predictor of “shared experience,” a key to descriptive representation for Mansbirdge (Mansbridge, 1999, p. 629). Carnes uses the framework of descriptive and substantive representation to explore whether this shared experience leads to substantive outcomes for the working class. If so, it is certainly consequential that this socioeconomic group has been represented at a rate 25 times lower than it proportionally might be in our nation’s highest legislative body (Carnes, 2013).

Ultimately, Carnes finds our lack of working-class representative to be consequential as our government pushes forward policies that harm working-class people at higher rates than they would if we had proportional representation. He conducts this analysis by looking at two data sets, including a detailed data set that looks at the full occupational histories of members of Congress from 1999-2008, and a simpler one that analyzes the most recent pre-election occupation of all members of Congress who served prior to 1997. Despite having two different sets of data, Carnes comes to several of the same findings. He discovers that blue- collar workers in general tend to be more liberal on economic issues, based on several roll-call based metrics. Specifically, he finds that lawmakers from working-class backgrounds “cast the most liberal votes” when compared to legislators from other professional backgrounds (Carnes, 2013, p. 46). Now, that is an important finding, but does the representation of this shared experience matter? Does it actually have an impact on policy outcomes in the United States? Carnes does acknowledge that this can be somewhat hard to measure as there is significantly limited data on working-class lawmakers. However, his data analysis shows that if the working class was proportionally represented in our nation’s highest legislative body, it would result in “one to six more major progressive economic policy outcomes in each Congress” (Carnes, 2013, p. 56). Thus, the underrepresentation of the working class results in less favorable policy outcomes for the group.

As just a few members of Congress come from the working class, it is very difficult to achieve policy outcomes for this group, with Carnes finding that although these representatives likely work harder to pass their economic bills, “the bills they introduce are killed off at an exceptionally high rate” (Carnes, 2013, p. 81). The presence of this underrepresentation in all levels of our nation’s legislatures causes tax policies to be more regressive, business regulations to be more relaxed, and social safety net programs to be less generous, all policy outcomes that negatively impact the lives of working-class Americans (Carnes, 2013). Carnes concludes that there are real consequences of having such severe underrepresentation of the working class in our country’s elected bodies. The ultimate outcome of this phenomenon is a white-collar government that is mostly focused on white-collar problems.

Connection of the Representation Problem to Mansbridge’s Work

When examining Carnes, we can use Mansbridge’s work to explain that the white- collar Congress substantively represents the interests of white-collar Americans because of their shared experience (Mansbridge, 1999). Despite making up less than 7% of our country’s current population, millionaires hold a majority in both chambers of Congress (Fleck 2023; Carnes, 2018). Carnes’ findings thus also relate closely to Mansbridge’s theoretical work that can help guide the scholarly discussion on descriptive and substantive representation through a more general lens. He shows his utilization of this framework in explaining how legislators, despite many pressures, have “their own values and beliefs influence what they do in office” (Carnes, 2013, p. 11). As such, having that shared experience leads to shared personal values that then leads to aligned preferences, ultimately impacting legislative behavior. As such, the work of Mansbridge helps show that for a disproportionately white-collar Congress, it makes sense that legislative behavior would be disproportionately focused on and in favor of white- collar preferences.

Political Participation and Symbolic Benefits of Descriptive Representation

Another issue with the underrepresentation of working-class citizens in America’s modern political institutions is that people with lower incomes are much less likely to vote in national elections than those with higher incomes (Stevens, 2020). As mentioned above, about 54% of the country belonged to the working class at the beginning of the 21st century, so, if they voted more often for working-class candidates, they could hypothetically have a very large sway in elections (Carnes, 2013). And interestingly enough, lower income Americans have been found to be more likely to distrust the government (Kasperkevic, 2015). Furthermore, part of the issue of our lack of representation of the working class, as Carnes explores in his 2018 book The Cash Ceiling: Why Only the Rich Run for Office–and What We Can Do about It, is that blue-collar workers do not run for office very often (Carnes 2018). So, that shared experience is lacking not only in elected bodies, but also in the ballot box, thus not giving us an opportunity to make an impact in addressing this severe underrepresentation.

There may be symbolic ways to address these negative feelings toward the political process. Matthew Hayes and Matthew V. Hibbing, in their 2017 article “The Symbolic Benefits of Descriptive and Substantive Representation,” find there are symbolic benefits associated with descriptive representation. In research with white and black Americans, the authors found that minority groups are more likely to see democratic representation as legitimate if they are descriptively represented: “To make decision-making more legitimate in the eyes of minorities and other disadvantaged groups, we should ensure that those groups have a fair say in the decision-making process” (Hayes & Hibbing, p. 47).

Mansbridge comments on this topic as well, saying that descriptive representation can improve “communication in contexts of mistrust” for both deliberation between constituents and representatives and between representatives themselves (Mansbridge, 1999, p. 628). She also argues benefits unrelated to direct substantive representation, in increasing social meaning for historically disadvantaged groups and increasing political institutions’ de facto legitimacy, can result from descriptive representation. These give background to Hayes and Hibbing’s data and put forth descriptive representation as a potential solution to the issue of distrust of lower-income Americans with our government. Because of both the data and background, Hayes and Hibbing’s conclusions are important and relevant to the discussions of these types of representation. There are symbolic benefits that come from descriptive representation, and substantive representation is not the only positive outcome of having more descriptive legislative bodies. This, combined with Carnes’ research on the connection between working-class descriptive and substantive representation, shows that descriptive representation can benefit the working class on multiple levels.

Phillips (2012) further explores the symbolic benefits of descriptive representation, giving a theoretical and textual analysis of descriptive representation. She concludes that “descriptive representation is not just a tool for achieving better substantive representation. It is something that matters in and of itself” (p. 516). Descriptive representation matters because “of what it symbolizes to us in terms of citizenship and inclusion- what it conveys to us about who does and who does not count as a full member of society” (p. 517). Thus, she argues descriptive representation allows historically marginalized groups to understand their worth in a society that does not always prioritize them. As lower-income Americans are more likely to distrust our government, descriptive representation conveying who matters as a citizen is vital. These symbolic benefits should not be taken lightly, especially for groups such as the working class that are so extremely underrepresented throughout America’s political institutions.

Further work may be done to show whether or not the symbolic benefits of descriptive representation, such as government being seen as more “fair and legitimate” by a group, leads to increases in political participation among the group (Hayes & Hibbing, 2017, p. 32). In turn, it could be discovered if electing more working-class people could lead to more political participation among such a group, which could yield multiple benefits. This potential gives a strong argument for why this other potential benefit of descriptive representation should be explored.

Perceptions of Working-Class Candidates

It is also vital to recognize if working-class candidates are perceived as capable by voters. Carnes explores this in both his second book and later 2016 article “Why are there so few working-class people in political office? Evidence from state legislatures,” ultimately finding that voters care most about personal characteristics in political candidates, not any specific background. And in analyzing data, he finds blue-collar workers possess some of these qualities more than white-collar workers and some of them less, with neither differing too significantly. In fact, working-class candidates are not even less likely to win elections, but rather “qualified workers rarely run in the first place” (Carnes, 2018, p. 71). This leads to Carnes concluding that we should focus on “‘demand- side’ forces” rather than “the supposed ‘supply-side’ shortcomings of the working class” (Carnes, 2016, p. 84). He thus argues that this lack of representation is not due voter’s preferences but rather institutional shortcomings.

Hoyt and DeShields (2020) also explore the perceptions of political candidates who come from less wealthy backgrounds, finding that voters tend to perceive these candidates as more liberal, likable, and trustworthy. Interestingly enough, liberal respondents indicated more positive evaluations toward these candidates, while the social class of the candidates did not influence the evaluation of more conservative respondents. Ultimately, Hoyt and DeShields agree with Carnes that “class-based biases do not play a central role in the overrepresentation of the elite in elected office” (Hoyt & DeShields, para. 77). Their data furthers this idea that it is not due to voter’s preferences that workers are not elected as many voters even perceive blue-collar candidates more positively. As such, it suddenly places even more issue with the lack of workers in our elected bodies. While witnessing our current level of underrepresentation and keeping in mind some of these favorable views of working-class candidates, it becomes clear our country’s “demand-side” problems are significant (Carnes, 2016, p. 84). Thus, these two texts show that one should not focus on voters’ preferences as the source of this representation problem. If anything, working-class candidates are perceived more favorably by some, and it would thus be incorrect to view voter perception as a real barrier to change.

Barriers to Working-Class Representation

If not voter preferences, what leads to working-class underrepresentation? Carnes (2018, 119) finds it is because working-class people run for office less often as they are “less likely to be recruited by political and civic leaders.” However, this is not due to “ambition,” which did not seem to be a consequential factor in the insufficient number of blue-collar workers in public office (Carnes, 2018, p. 117). In fact, Carnes finds that when working-class individuals are connected to recruiters in campaign and party staffs, they are more likely to end up holding office. However, elite recruiters tend to look to their own circles while recruiting, thus excluding working-class people from this important part in the election process. Furthermore, blue-collar workers cannot always overcome the political hurdles and provide the time and resources needed to campaign (Carnes, 2018). After all, “many qualified working-class Americans simply can’t put their jobs and lives on hold to campaign” (Carnes, 2018, p. 119). The realities of working-class people’s lives impact their ability to run for office. Carnes’ work finds that workers hold fewer offices in cities with more burdensome elections and more workers run and succeed in states with stronger labor unions. All in all, his work helps show the barriers to working-class individuals running in elections and ultimately holding political office.

The Importance of Labor Unions

Carnes’ point about labor unions is one that is very relevant to this discussion. In discussing unions, he states that they “close the social gaps that normally keep workers out of sight and out of mind to candidate recruiters” (Carnes, 2018, p. 152). The presence of unions can help “talented blue-collar Americans” to be involved and connected with different actors significant to elections (Carnes, 2018, p. 151). The data Carnes analyzes shows that in the most unionized states in the country, blue-collar workers have historically held two percent more state legislative seats while running for three percent more of such seats. Even when controlling for other factors of indirect ways unions might encourage the election of working- class candidates, this relationship is strong. This relationship should be all that surprising.

Unions serve as a form of substantive representation outside of traditional political institutions for workers. In regard to the pushing forward of a group’s interests, unions focus heavily on this task and how they can be used to better the lives, rights, and conditions of workers. They allow people to participate in pushing for their interests, so they better focus on this participatory role that we have defined as key to a successful democracy. As such, we can see how increasing worker participation could lead to eventual improvements in the descriptive representation of workers in our more traditional political institutions. Unions have the ability to mobilize people while pushing for the better treatment of workers, including their descriptive representation. As we know this is connected to substantive representation inside political institutions, unions in a way achieve substantive representation for the working class both within and outside of legislative bodies.

Additionally, labor unions can also address the issue of the lack of political participation among the working class. Francia (2012) finds that unions are significant to elections as they increase voter turnout, despite recent declines in the percentage of the workforce that are members of unions. Carnes describes how labor scholars have often argued that unions help members of the American working-class learn “civic values and political skills” (Carnes, 2018, p. 151). Francia’s analysis falls in line with this as he explains how research has found that “participation in organizations… provides individuals with opportunities to develop their civic skills and to improve their political knowledge and awareness” (p. 6). He relates this to the context of unions, where membership helps to increase voter turnout. Furthermore, Francia shows that unions also increase turnout for low and middle-income individuals. He articulates the importance of this quite well by explaining “this not only has potentially important electoral consequences, but arguably fosters a healthier democracy by making the electorate more representative of the larger population” (p. 20). Here, descriptive representation is shown of the people who are present at the polls. And when these people that may belong to the working class are involved in unions, it can be hoped that their improved likelihood of politically participating leads to growth in both the descriptive and substantive representation of the working class in America’s actual political institutions as opposed to the country’s current white-collar government. These effects of union membership help create democratic representation that is more participatory, and they thus show the importance of unions in achieving improvements in working-class representation.

Furthermore, Francia touches on how union households have and still do strongly support Democratic candidates for federal elected positions (Francia, 2012). This can be connected to Carnes’ findings that working-class people and officeholders tend to be more liberal specifically toward economic issues. Ultimately then, Francia and Carnes show that unions increase political participation and the descriptive and thus substantive representation of the working class. With an increased focus on strengthening unions in the future, we could look to address our country’s representation problems by mobilizing workers to encourage and help other workers run for and win office. There is certainly more work that needs to be done on exactly how unions increase working-class descriptive representation in 2023, but Carnes and Francia’s findings stage unions as a promising mechanism for addressing this extreme underrepresentation problem in America.

Other Potential Mechanisms for Addressing Working-Class Underrepresentation

Beyond his discussion of unions, Carnes also addresses that it is a waste of time to focus on unrealistic reforms such as quotas based on social class or random selection of politicians (Carnes, 2018, p. 207). Furthermore, other potential reforms that may be proposed by people, such as pay raises and public financing, are not useful as they do not actually help workers get into office (Carnes, 2018). Instead, ideas for reforms that have more potential include “candidate training programs for workers, scholarships for working class candidates, and seed money programs targeting workers” (Carnes, 2018, p. 207). Continued research into these reform ideas will be beneficial in determining how our country can most effectively address and remedy our extreme underrepresentation of the working class.

Comprehensive Effects of Descriptive Representation

Descriptive representation of the working class may also lead to other changes in lawmaker actions. Makse (2019) uses state legislator data to analyze “perspective[s]” of lawmakers from different occupational backgrounds, which he finds do not just impact the traditional measure of roll-call voting, but also how they perceive their constituencies, campaign, communicate with their electorates, and view their roles (p. 324). This is important because it shows that social class changes how legislators act in a very broad sense. If one sets any value to having diverse perspectives in elected bodies, which is important for a country with diverse populations, then leaving out a shared perspective that such a large portion of our country possesses is doing a great injustice to that group. And as Mansbridge shares, especially during deliberation where agendas are set for what elected bodies will focus on, “perspectives are less easily represented by nondescriptive representatives” (Mansbridge, 1999, p. 365). Makse’s conclusions show it is important to increase the diversity of deliberation among representatives within American elected bodies, but also outside of them, where representatives communicate with their electorate and become aware of their beliefs, concerns, and perspectives.

The Potential Drawback of Descriptive Representation

It is necessary to address the potential drawback of prioritizing descriptive representation with any characteristic. Jones (2016), for instance, discovers how descriptive representation can reduce accountability for lawmakers. In analyzing data from respondents, Jones found that descriptive representation, in terms of race, can increase the perception of substantive representation being performed by legislators regardless of their actual policy actions, thus lessening the accountability they face. He thus concludes there is a “need to reevaluate the normative value of descriptive representation,” showing we must assess representation in a more comprehensive way (p. 697). This overall conception can be related to George Santos. If he was assessed on his descriptive characteristics rather than his actions, his accountability would be reduced and members of the LGBTQ+ community might support him despite the fact he acted in harmful ways toward this group he should have hypothetically been representing the substantive interests of during his time in office. Unlike Carol Moseley-Braun, his representation did not result in substantive outcomes that benefited the group he descriptively represented.

While Jones makes an important point in how descriptive representation cannot be treated as an end in itself, the good news is that data primarily supplied through Carnes shows that descriptive representation of working-class individuals in our elected bodies is directly linked to substantive representation of the working class. Direct data on the perceptions of the substantive representation of working-class representatives may not be readily available, but their actual substantive representation ensures reduced accountability is not a problem in this context. Blue-collar representatives vote more for policies that look to benefit the working class, they cosponsor economic bills more often, they devote more time and resources to these issues, and more (Cannes, 2013). At the end of the day, the data Carnes engages with shows that descriptive representation of working-class people in our political institutions has led to substantive representation. While Jones provides data showing the risk of relying too much on descriptive representation, his points are not relevant in this context of the representation of the working class as data shows the strong relationship between descriptive and substantive representation of working-class people.

The Importance of Intersectionality

Discussions of this topic must address a complexity of representation that exists in intersectionality. In going back to Phillips’s work, she discusses how we cannot address the underrepresentation of historically underprivileged groups without addressing the intersections of this underrepresentation (Phillips, 2012). Intersectionality, a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in her 1998 work “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics,” describes how social classifications are interdependent in their discriminations against people. So, when it comes to America’s working class, it must be recognized that some workers possess identities with intersecting forms of discrimination. This relates to representation as not all the individual identities of working-class people are represented in government to the same extent. Representation disparities exist in measures such as race, gender, religion, and sexuality in our current Congress, and we must consider these when discussing working class representation (Schaeffer, 2023). Overall, viewing the working class as homogeneous limits our analysis of the impacts of underrepresentation on different people within this group.

Phillips addresses intersectionality but brings up an important point. She shares “it is no easy matter to identify mechanisms that can adequately reflect the intersectionality of all relevant forms of political exclusion” (Phillips, 2012, p. 516). In regard to this, a truly proportional political institution would require complex analysis of all possible measures just to figure out what the complexion would look like. The ultimate point is that it is probably impossible to have a truly proportional political institution in a country with our diverse identities. That being said, the implication of intersectionality in analyses of the underrepresentation of the working class must be considered as research goes forward. If the reality of intersectionality is ignored when it comes to the underrepresentation of the working class, it will not be fair toward certain individuals that are more underrepresented than others within this group. If the goal is to increase representation of all groups, discussions must be had on how the working class, and the complexities within the group, can be represented comprehensively. This demands addressing intersectionality and representation for all, even if it may not be practical to achieve it at a perfect level.

Literature Review Conclusion

Ultimately, the available literature makes it clear that America faces a representation problem. The country’s working class is greatly underrepresented in its legislative bodies, which has a direct effect on people’s lives. Its modern democracy is failing because ordinary people do not possess political power. If their shared experiences are not being represented, one cannot be confident that their needs will be either. And with all of this, intersectionality is an issue that must be kept in mind when discussing how to improve representation for historically marginalized groups. What is clear is that America’s government is a severely limited representation of its actual population. There are various barriers to working-class people running for office, and potential reforms exist as well that further research can give a better understanding of.

As such, there is still work to be done. Despite a strong analysis by Carnes, his first book is a decade old. As the world continues to progress, it is necessary to assess any change in working-class representation and the factors associated with it. Ultimately, the American working-class deserves better descriptive and substantive representation in the country’s political institutions, and more effort must be paid to achieving this end to create a more representational government that serves all Americans.

Data Analysis

Introduction to Data on Furthering Carnes’ WorkIn hoping to address this, I began by working to fill in the gaps since Carnes’ initial research. The primary work done in White-Collar Government focuses on working-class representation in our country’s history up to the 110th Congress, which took place from January 3, 2007 to January 3, 2009 (Carnes, 2013). As such, working-class representation has not been so comprehensively studied since this time, and I began this section of my research by looking at such representation from the 111th Congress through the current 118th Congress (2009-2024). Using Congressional Quarterly’s House Profiles files, published journals from the Almanac of American Politics, and Carnes’ CLASS dataset, I was able to collect prior occupational data on every member of the House of Representatives in the past eight Congresses (excluding non-voting members). This resulted in 996 unique members from the past 15 or so years. I marked whether or not these individuals were ever “blue-collar” workers according to Carnes’ criteria of manual labor, service-industry, or union workers, and this helped me develop descriptive data on the working-class occupation of Congress since 2009. To simplify the coding, I ascertained whether or not each representative had any working- class experience. Although Carnes coded blue-collar workers as those that spent at least a quarter of their prior career in blue-collar occupations or those that last worked in a blue-collar occupation, due to data limitations, I could not view such specifics of the occupational histories of every member of Congress since 2009. Nevertheless, as I will show, even my generous coding of “working class” shows greatly limited representation for this social group.

One quick note to make is that I did not analyze senators and their occupations from each of these Congresses. I initially did so for the ongoing 118th Congress, but found that it was not as productive as collecting data on the House of Representatives as senators are elected for six-year terms. Thus, the composition does not change nearly as frequently. From the data on the Senate in the 118th Congress, I found that just two senators, New Mexico’s Ben Ray Luján and Iowa’s Chuck Grassley, had any working-class experience prior to entering office (Carnes, 2016; Congressional Quarterly, 2010). These senators worked as a casino dealer and an assembly line worker, respectively. However, the remaining 98 members of the Senate in the current Congress held no working-class profession prior to entering their office. Thus, the body as a whole had just 4% of its members have blue-collar experience.

Turning the attention back to the House of Representatives, the 996 unique members served a total of 3,480 terms over the course of the last eight Congresses.1 Of these 3,480 terms, 188 were served by an individual with some blue-collar experience prior to their election or appointment. The other 3,292 did not have any working-class experience as listed in their professional histories from the various sources. This is a rate of 5.4% for the descriptive representation of blue-collar workers in Congress, which again is nowhere near proportional to the general working-class population of the country. In fact, this number is about ten times less than what Carnes finds to be the proportion of America that belongs to the working class. Again, Carnes’ 2% representation is lower than my 5.4% due to our different criteria for measuring working-class representation, but this brings up an important point. I have a lower threshold for what counts as working-class experience, but I still see great disparities with my 5.4%. For a country that has had at least half of its population belong to the working class since the start of the 20th century, this remains incredibly inadequate (Carnes, 2018). So, while this number might look like progress at first, regardless of differences in measuring, it is still clear that we are nowhere near proportional representation of working-class Americans in our nation’s highest legislative bodies. Furthermore, if we find substantive representation to exist for this group, then it would show that people who have any working-class experience are more well-suited to represent the working class. As such, my methods are not identical to those of Carnes, but they have the potential to provide their own significant insight nonetheless.

One last point to make on this pure descriptive data really helps illustrate the fact that we are nowhere near having descriptive representation for the working class in America.

[1)Through the end of 2023, for terms with members who retired, passed away, or left office for any other reason, I only gathered data on the member who served the largest portion of the term as the member serving that term.]

When I analyzed the 62 new members of the House of Representatives that were elected for and served in the 117th Congress, not a single individual had working-class experience prior to their election (Congressional Quarterly, 2020). The fact that this many individuals did not have any working-class experience in such a recent election cycle makes it abundantly clear that we are nowhere close to solving this problem in America. It is almost unfathomable that such a trend would exist, but the validity of Carnes’ conception of our country’s white-collar government certainly continues to live on.

Descriptive Findings

Party

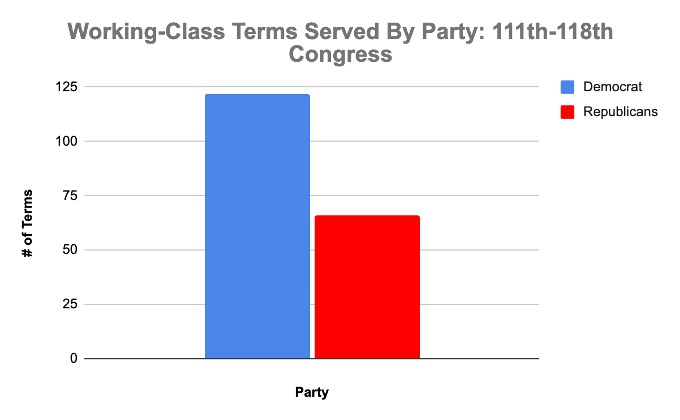

By using the dataset I created, I found that from the 111th Congress until now, 1,704 terms have been served by Democratic representatives while 1,776 terms have been served by Republican ones. As mentioned above, 188 of the 3,480 total terms served since 2009, or 5.4%, have been my members with any experience in blue-collar occupations. After finding this basic descriptive data, I hoped to analyze how the party variable was related to the working-class representation variable. As can be seen in Figure 1, from the 188 terms served by representatives from working-class backgrounds, 122 of them were served by Democrats while just 66 were served by Republicans.2 This is an interesting finding as Republicans even have a slight edge in the number of terms served since 2009, yet the number of terms served by individuals with blue-collar experience is significantly higher for Democrats than Republicans. As such, it is clear that there is a significant difference with regards to party between working-class representatives and non-working-class representatives that serve terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. From face-value, this would seem to indicate that working-class representation is significant because of such an extreme partisan difference. The underrepresentation of the working-class would mean the underrepresentation of these particular perspectives and views that are associated more so with Democrats than Republicans. Again, analyzing substantive representation is more important than descriptive party representation, and it will be addressed momentarily. This data remains significant though, and it shows one clear difference between the general set of all terms that leans slightly Republican, and the set of blue-collar representative terms that has a heavy leaning toward Democrats.

[2) A chi-squared test found this relationship to be statistically significant: x2 = 19.456, p < 0.01]

Figure 1: Working-Class Terms Served by Party: 111th-118th Congress

State

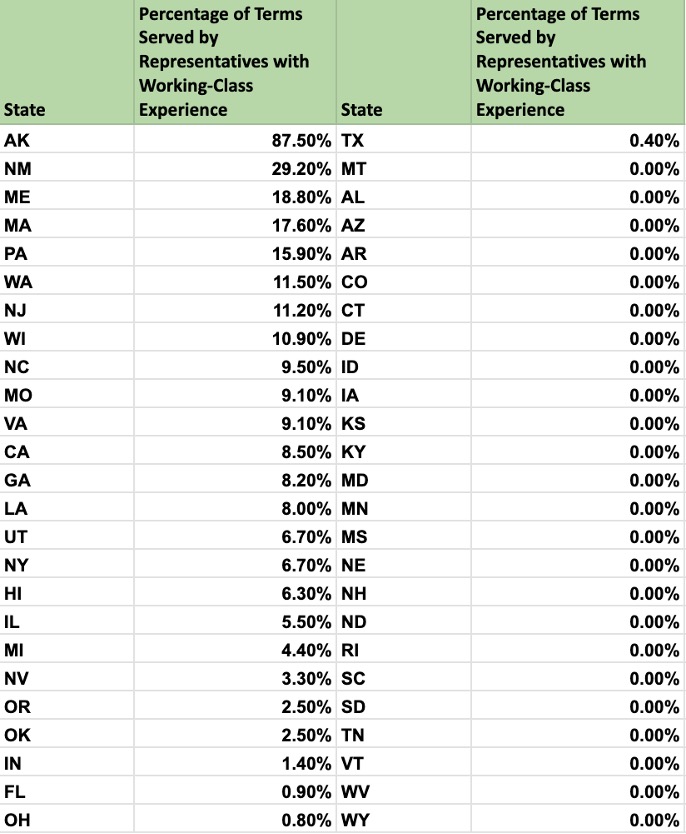

I also collected data on the states of all members of the House of Representatives since 2009, and in turn calculated and analyzed the proportion of these terms for each state that was served by a member with working-class experience. Notably, 24 out of the 50 states did not have a single working-class representative serve for any term in the last eight Congresses. One state that was noteworthy among these was Tennessee, which has had 72 terms served in that timeframe without a single one of them being served by a prior member of the working class. Another state of note is Texas, which has had 282 terms in this timeframe with just a single term being served by a member of the working class. This term is currently being served by former labor organizer Democrat Greg Casar in the 118th Congress (Congressional Quarterly, 2023).

On the opposite side, some states had notable proportions of representation from working-class representatives. Alaska had 88% of their terms being served by such candidates since 2009, although this is just 7 out of the 8 possible terms due to the long-serving Don Young. New Mexico also had 7 out of 24 terms served by working-class representatives, for a total of 29%. Some states with higher percentages of working-class representation with larger overall delegations include 17.6% of the 74 terms served in Massachusetts, 11.5% of the 78 terms served in Washington, 11.2% of the 98 terms served in New Jersey, and 15.9% of the 145 terms served in Pennsylvania. While these data are limited, they do reveal that certain states have yielded more terms where representatives with working-class experience are present. Figure 2 shows each states’ percentage of working-class representation in the terms served since the start of the 111th Congress.

Updated Data on Working-Class Americans’ Views

While the descriptive underrepresentation of the working class is still severe, it is again important to turn to substantive representation when looking at these issues. Before viewing that, however, all of this should be addressed in relation to the general views of current working-class Americans. Carnes states how blue-collar Americans tend to be more liberal on economic issues, so I hoped to investigate this as well (Carnes, 2013). A 2023 HarrisX poll for Deseret News was conducted that focused on members of the country’s working class and their current perceptions of America (Collins & Bates, 2023). The results of this poll made it clear that working-class Americans are still clearly frustrated with the country, matching with what I had discussed earlier with this distrust toward the American government. In total, 64% of registered voters who identified as belonging to the country’s working class said that they believe America was “on the wrong track” as opposed to 27% who believe it was currently on the right track. However, just 57% of all registered voters felt the country was on the wrong track while 32% felt it was on the right track. Furthermore, 52% of working-class voters stated that their personal finance situation was becoming worse, while 20% said it was getting better. Just 40% of all registered voters felt their personal financial situation was becoming worse, while 31% said it was becoming better. While there was not a lot of clarity on the direct political leanings of the working class from this poll, it was rates than all registered voters taken together did.

In a 2018 brief titled “The Working-Class Push for Progressive Economic Policies,” authors Alex Rowell and David Madland analyze data concerning working-class Americans. Using survey data from four major surveys conducted in 2016 and 2017, the authors analyzed the political views of members of the country’s working class, defining it as being made up of individuals who do not possess a college degree. Although this was a different definition than that of Carnes, it still helped illustrate the views of many of these Americans. It was found that 58% of white working-class individuals supported raising the country’s minimum wage, while Black and Hispanic working-class individuals supported this policy at rates of 81% and 68%, respectively. When it comes to “expanding access to paid leave,” white working-class members supported such a pursuit at a rate of 63%, Hispanic working-class members at 69%, and black working-class members at 72%. Requiring equal pay for men and women saw white, black, and Hispanic working-class individuals supporting the policy at 86%, 82%, and 85%, respectively. Similarly high rates were found for supporting government health care for the sick, increased government spending on health and retirement, free public college tuition, raising taxes on the rich, and more. Thus, the brief’s data collection shows that there are many economic-based issues that working-class people tend to lean more liberal on, with many of the data on these issues showing that members of the working-class who experience intersectionality are even more in favor of these liberal policies.

While some of the direction of the overall political leanings of working-class Americans are unclear toward one side or the other, data discussed in this brief shows support for specific liberal economic policies that often seek to address the economic disparities that exist in this country (Rowell & Madland, 2018). Perhaps even more clear is the fact that members of the working class feel that the country and its government does not support them (Collins & Bates, 2023). The distrust of the government seems to have a strong consensus among the working class, and that may be at least partially a result of this group not being prioritized in Congress. So, when we analyze how working-class representatives represent these constituents, it is key to see how they vote, and if it is different from members who did not belong to the working class prior to their elections. If we find a relationship as Carnes did, then it shows that the absence of working-class representatives in Congress is consequential to the substantive representation of this social class and the policy outcomes they would hope for.

Substantive Findings: Methodology

Following in the footsteps of Carnes, I utilized first dimension DW- NOMINATE scores for each member of Congress as a measure of their overall liberal to conservative (or left to right) voting record on economic issues. DW-NOMINATE is a scaling measure that compares the roll call voting behavior of each member to every other member, and then scales those differences on n-dimensions. The first dimension, though not expressly measuring the preference of members of Congress on just economic issues, is typically interpreted as capturing the differences among members of Congress in their voting on standard left-to-right political-economic dimension. I collected these data for all 992 House members across the 111th-118th congresses from Voteview’s Congressional Roll-Call Votes Database3. Then, combined with my prior work in gathering occupational data, I was able to see whether or not there were significant differences between members who had previously held working-class occupations and members who had not in their roll call voting. For these scores, negative numbers are associated with more liberal voting, while positive ones are associated with conservative voting.[3) https://voteview.com/data]

I also collected data on AFL-CIO’s Legislator Voting Records for each member in my dataset via the AFL-CIO’s website. I found the lifetime scores to be most useful in my analysis as individual Congress scores did not exist for all members, especially in regard to partial terms. The AFL-CIO states that their voting scores “let[] you know where your lawmakers stand on issues important to working families, including strengthening Social Security and Medicare, freedom to join a union, improving workplace safety and more” (AFL- CIO, 2024). These scores are measured by percentages, where higher percentages are typically associated more pro-worker voting while lower percentages are typically associated less pro- worker voting.

Finally, I collected data on Cook Political Report’s Partisan Voter Index (PVI) Scores, which measure each congressional district’s partisan leanings during a given congress. This is important to take into account as members of Congress are individuals who often seek reelection and thus have incentive to be responsive to the political leanings of their districts (Mayhew, 1974). In other words, we can expect and see from the data that members representing more left-leaning (or Democratic-leaning) districts tend to vote more liberally and more pro-worker. For members during the 112th and 117th Congresses where major redistricting would happen for the following Congress, I used the PVI scores for the seats or districts which the members would run in for the next Congress. If the district was abolished and a member did not succeed in a different district, I just used its current PVI score for that district. If the district did not yet exist that a member would then represent or be succeeded in, I used the district’s PVI score in the next Congress. I also adjusted PVI scores for Pennsylvania between the 115th to 116th Congresses as they underwent significant redistricting in 2019.

Furthermore, as partially discussed above, I collected various data on each member of Congress, including their states, party, districts, several identification codes, members who served incomplete terms, and years of prior experience in Congress during the time measured. I collected these measures from the various sources I used to collect data on working-class representation and voting scores as listed above. After collecting all this data, I conducted many different tests on the data to analyze the strength of different relationships between various variables.

Bivariate Findings

First, I will analyze any relationship between working-class backgrounds of members of Congress and their voting behavior in a bivariate fashion. I ran each analysis for all 3,480 member-congress observations, but also for just the terms that were served by members who had complete terms in office. However, there was not too much variation here between the averages and relationships for the data with all of the terms and the data with only the complete terms. I denoted in parentheses the average voting scores for members who only served complete terms. Due to the low level of variation between these two sets of data, all figures shown display the dataset that include all terms I analyzed. Furthermore, I ran both linear regression models and t-tests for means for all the data I looked at, and the results of the tests for the data group with all of the terms served are included in figures below.[4)All t-tests for means assume equal variance.]

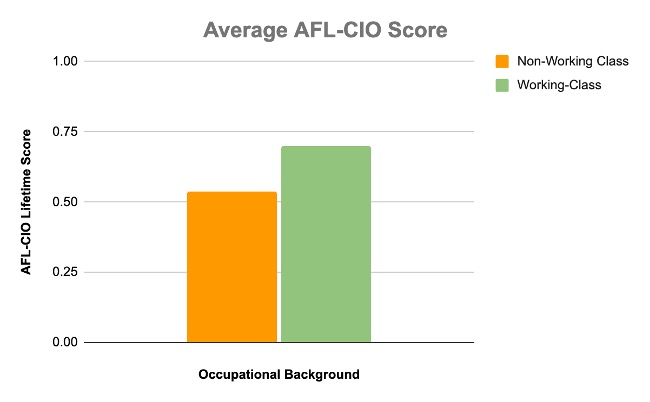

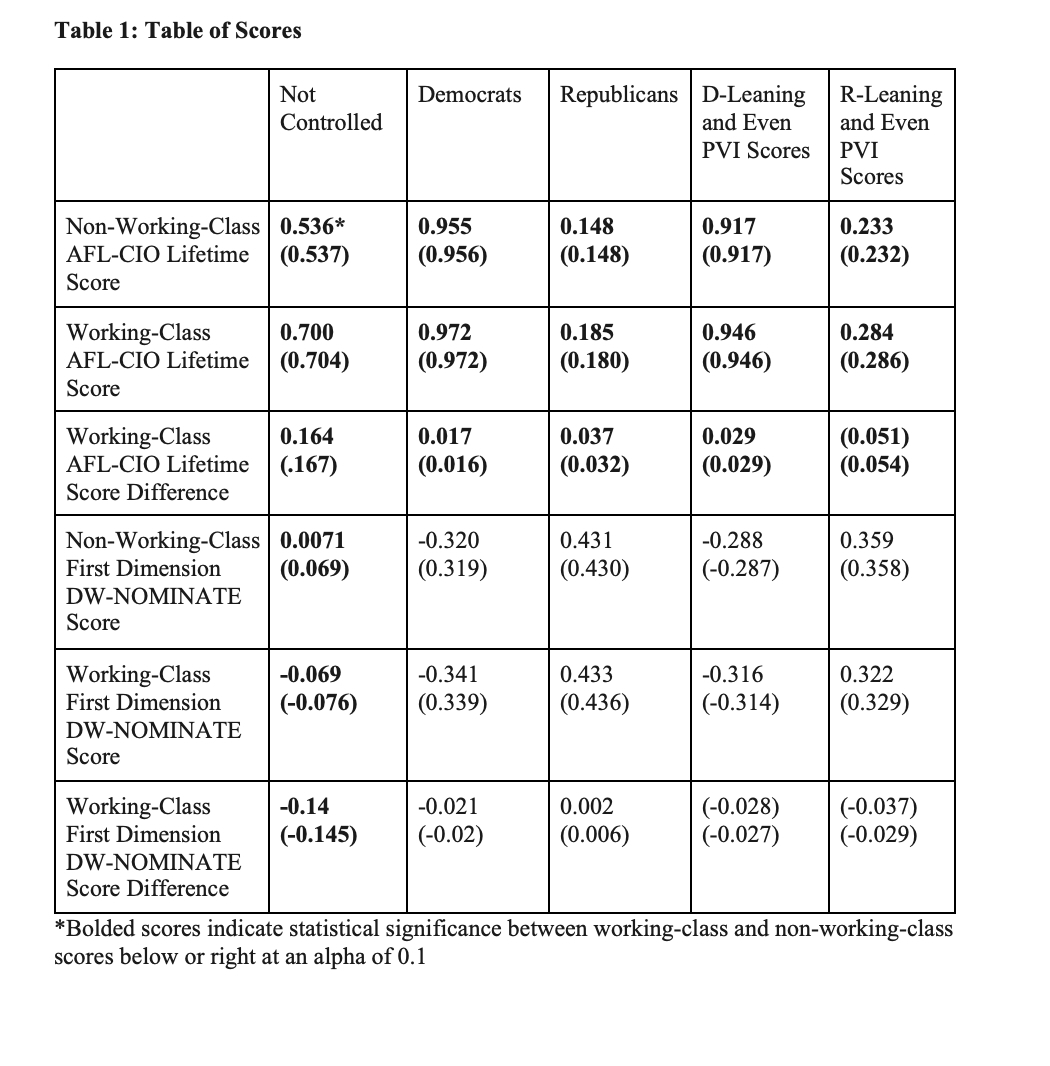

Again, Carnes found that, in regard to economic issues, working-class representatives “cast the most liberal votes” when compared to representatives from other occupational backgrounds (Carnes, 2013, p. 46). And when looking at AFL-CIO lifetime scores, this trend seems to have continued. The mean AFL-CIO lifetime score for non-working-class members was 0.536 (0.537), while it was 0.700 (0.704) for members who had working-class experience. This difference for the full-term members can be seen in Figure 3. As the scores were higher on the AFL-CIO scale, this indicates more liberal voting on the issues important to working families, which largely relate to economic issues. The linear regression models and t-tests both gave me the same answer: the difference in means and the linear relationship between working-class experience and AFL-CIO lifetime scores was statistically significant.[5 (t = -5.1481, p = 2.7773-07)] As such, without controlling for any variables, a relationship can definitely be concluded between these two variables.

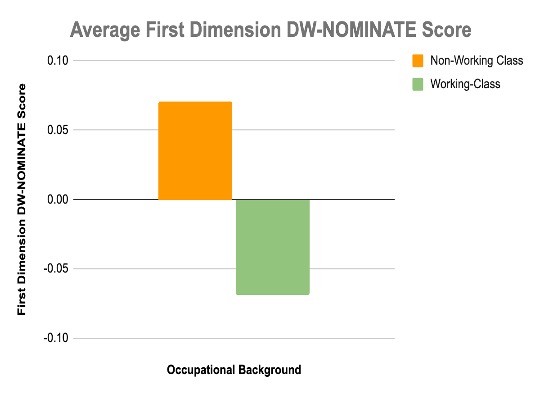

When it comes to first dimension DW- NOMINATE scores, I largely came to the same findings when not controlling for any variables. The average score for non-working-class members was 0.071 (0.069), while it was -0.069 (-0.076) for working-class members. This showed a conservative leaning for members with no working-class experience, while a liberal leaning for members with working-class experience. These can be seen in Figure 4. Again, this relationship was found to be statistically significant. [6 (t = 4.1146, p = 3.968e-05)]

When it comes to first dimension DW- NOMINATE scores, I largely came to the same findings when not controlling for any variables. The average score for non-working-class members was 0.071 (0.069), while it was -0.069 (-0.076) for working-class members. This showed a conservative leaning for members with no working-class experience, while a liberal leaning for members with working-class experience. These can be seen in Figure 4. Again, this relationship was found to be statistically significant. [6 (t = 4.1146, p = 3.968e-05)]Just like AFL-CIO lifetime scores, working-class experience seemed to have a clear relationship with voting records that followed the same liberal direction that Carnes found in his work.

Figure 4: Non-Controlled First Dimension DW-NOMINATE Scores Controlling for Party

Controlling for Party

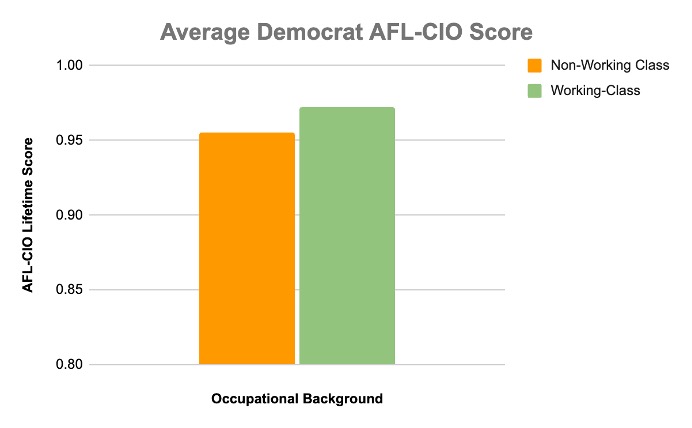

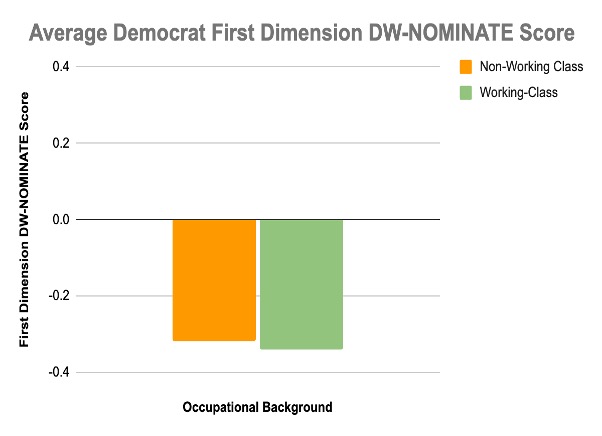

Figure 5: Democrat AFL-CIO Lifetime Scores When it comes to First Dimension DW-NOMINATE scores, the mean score for non- working-class Democrats was -0.320 (-0.319), while the score for working-class Democrats was -0.341 (-0.339). This relationship is shown in Figure 6, and again shows a liberal difference in means. However, this relationship was not found to be statistically significant.8

When it comes to First Dimension DW-NOMINATE scores, the mean score for non- working-class Democrats was -0.320 (-0.319), while the score for working-class Democrats was -0.341 (-0.339). This relationship is shown in Figure 6, and again shows a liberal difference in means. However, this relationship was not found to be statistically significant.8

Figure 6: Democrat First Dimension DW-NOMINATE Scores 7 (t = -2.3818, p = 0.01734)

7 (t = -2.3818, p = 0.01734)

8 (t = 0.91759, p = 0.359)

Republicans

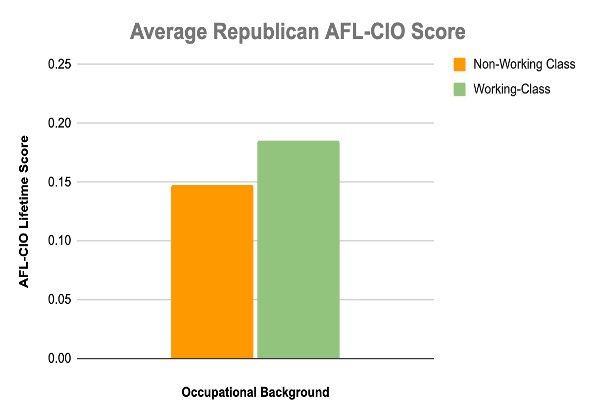

For Republicans, the mean AFL-CIO lifetime score was 0.148 (0.148) for non- working-class Republicans, while it was 0.185 (0.180) for working-class Republicans. This is shown in Figure 7, and, again, it shows another difference in means that leans more liberal for working-class representatives. This relationship was also found to be statistically significant.9

Figure 7: Republican AFL-CIO Lifetime Scores

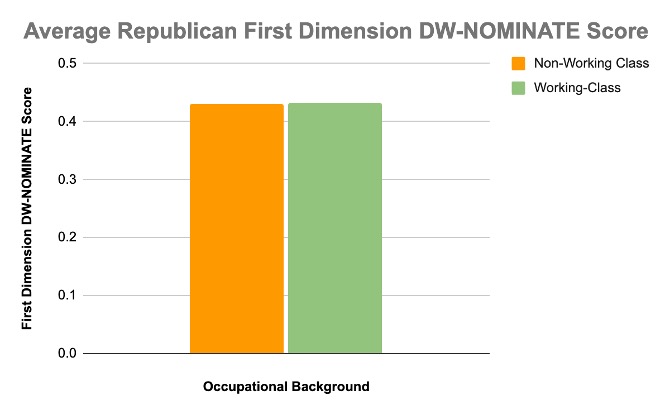

For First Dimension DW-NOMINATE scores, the mean score for non-working-class Republicans was 0.431 (0.430), while the mean score for working-class Republicans was

For First Dimension DW-NOMINATE scores, the mean score for non-working-class Republicans was 0.431 (0.430), while the mean score for working-class Republicans was

0.433 (0.436). This relationship is shown in Figure 8, and it actually shows a slight conservative leaning for the working-class representatives of the Republican party. However, this relationship was not found to be statistically significant at all with tests resulting in an extremely high p-value.10

Figure 8: Republican First Dimension DW-NOMINATE Scores PVI Scores

PVI Scores

After controlling for party in running this data, I did the same for PVI scores. I decided to stratify the scores by separating all of the Democrat-leaning and even districts with the Republican-leaning and even districts. Democrat-leaning districts are those with PVI scores

9 (t = -2.5685, p = 0.0103)

10 (t = -0.052235, p = 0.9583)

that have a partisan leaning toward the Democrat side, while Republican-leaning districts are those with a leaning toward the Republican side. Even districts are those with partisan leanings in between the two sides. I ran the data for each of these sides along the even districts to appropriately account for the even districts while seeing if each side still maintained a relationship between working-class experience and voting record when controlling for district PVI scores.

Dem-Leaning and Even Districts

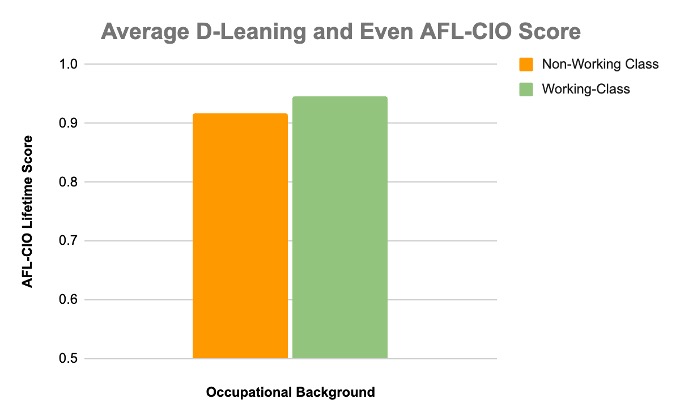

For members of Congress in Dem-leaning or even districts, the mean AFL-CIO lifetime score was 0.917 (0.917), while it was 0.946 (0.946) for working-class members. This relationship shows a liberal difference as shown in Figure 9. This relationship was found to be just statistically significant when using an alpha of 0.1.11

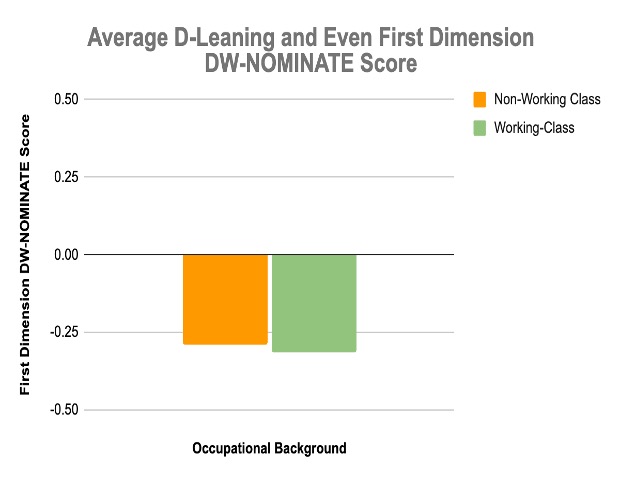

Figure 9: AFL-CIO Lifetime Scores for D-Leaning and even districts For First Dimension DW-NOMINATE scores, members of Congress from D-leaning or even districts who did not come from working-class backgrounds had an average score of – 0.288 (-0.287), while those from working-class backgrounds had an average score of -0.316 (- 0.314). This is a yet another liberal difference as shown in Figure 10. However, this was not found to be statistically significant.1211 (t = -1.6469, p = 0.0977)

For First Dimension DW-NOMINATE scores, members of Congress from D-leaning or even districts who did not come from working-class backgrounds had an average score of – 0.288 (-0.287), while those from working-class backgrounds had an average score of -0.316 (- 0.314). This is a yet another liberal difference as shown in Figure 10. However, this was not found to be statistically significant.1211 (t = -1.6469, p = 0.0977)

12 (t = 0.98434, p = 0.3251)

Figure 10: First Dimension DW-NOMINATE Scores for D-Leaning and even districts R-Leaning and Even Districts

R-Leaning and Even Districts

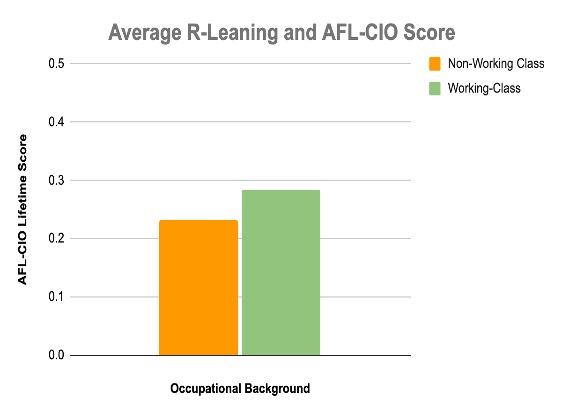

Finally, for members of Congress in R-leaning or even districts, the mean AFL-CIO lifetime score was 0.233 (0.232), while it was 0.284 (0.286) for working-class members. This relationship shows yet another liberal difference as shown in Figure 11. Models I ran found the p-value to be just above 0.1, so I believe an argument could be made for statistical significance for this relationship at an alpha of 0.1.13

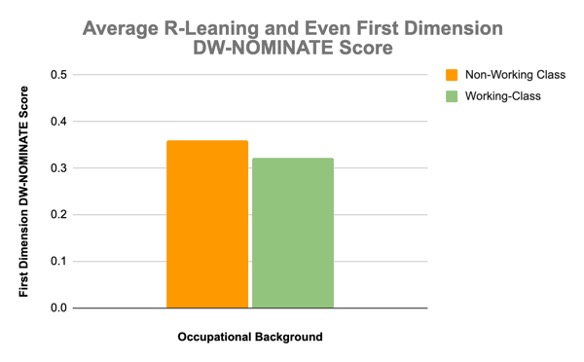

Figure 11: AFL-CIO Lifetime Scores for R-Leaning and even districts For First Dimension DW-NOMINATE scores, members of Congress from R-leaning and even districts who did not come from working-class backgrounds had an average score of0.359 (0.358), while those from working-class backgrounds had an average score of 0.322 (0.329). This is another liberal difference as shown in Figure 12. However, this was not found to be statistically significant.14

For First Dimension DW-NOMINATE scores, members of Congress from R-leaning and even districts who did not come from working-class backgrounds had an average score of0.359 (0.358), while those from working-class backgrounds had an average score of 0.322 (0.329). This is another liberal difference as shown in Figure 12. However, this was not found to be statistically significant.14

13 (t = -1.6067, p = 0.1083)

14 (t = 0.68587, p = 0.4929)

Figure 12: First Dimension DW-NOMINATE Scores for R-Leaning and even districts

*Bolded scores indicate statistical significance between working-class and non-working-class scores below or right at an alpha of 0.1

Discussion

From these results, as clearly laid out in Table 1 with the same format as the discussion of data above, we can come to a few conclusions. First off, working-class experience is definitely significantly correlated both with AFL-CIO lifetime scores and First Dimension DW-NOMINATE scores without controlling for any variables. Second, even when we do control separately for party and PVI scores, we still see statistical significance with the relationship between working-class experience and AFL-CIO lifetime scores. This is not seen for DW-NOMINATE scores however, which may be explained more so by party and PVI scores. However, even when keeping this in mind, seven out of the eight measures I looked at white controlling for either party of PVI score found working-class representatives to vote more liberally than non-working-class representatives, with the one exception being working- class Republicans on DW-NOMINATE scores (with a minute conservative difference of 0.002 that was nowhere close to being statistically significant). Thirdly, we can note that the differences between non-working-class members’ votes and those of working-class members are generally larger in Republicans than in Democrats. This is interesting as it shows how working-class experience may be especially influential for the GOP.

All in all, we can see that working-class experience clearly has both a direct impact on AFL-CIO scores, and a more indirect impact on First Dimension DW-NOMINATE scores, where it influences party and PVI scores which then heavily influence these scores. I find AFL-CIO scores as AFL-CIO defines them to be a more accurate measure of working-class experience and views, and these scores certainly have a relationship with working-class experience for members of Congress.

As Carnes and I may have had a different threshold for what constituted working-class experience, my findings hold some unique significance. Carnes clearly showed that in the past, members of Congress with significant blue-collar backgrounds tended to vote more liberally on economic issues. Now, with my work, this trend has been shown to continue in the last 15 years for members with any working-class experience. This shows that any time spent working in blue-collar occupations tends to lead to more liberal voting on economic issues for members. As such, a general conclusion falls in line with Carnes’ previous findings and even goes a bit further by showing the relationship to exist for members with any working-class experience. Both indirectly or directly, working-class experience leads to more liberal voting on economic issues. And, with our findings about working-class Americans’ views on many economic issues as well as those of Carnes’ work, we can conclude that descriptive representation for the American working class certainly leads to better substantive representation for the American working class.

ConclusionMy work has found that the descriptive representation of the working class is still unfortunately very lackluster. However, it has also discovered that the representation that does exist leads to better substantive representation for this social group. As our country looks to improve the lives of its different underrepresented groups, we must realize that not only is the working class underrepresented, but increasing representation for it leads to better outcomes for the group. Whether for symbolic descriptive representation benefits or outcome-focused substantive representation benefits, increasing representation of the working class in our country will directly improve the lives of this group, and thus we must start making a stronger effort to elect candidates to Congress who come from the same backgrounds as everyday Americans.

References

AFL-CIO. (2024). Legislator voting records: AFL-CIO. https://aflcio.org/scorecard/legislators Baska, M. (2023, January 24). Gay Republican George Santos has a grim anti

LGBTQ+ record. PinkNews. https://www.thepinknews.com/2023/01/24/george-santos-gay- republican lgbtq-issues/

Barone, M., & Cohen, R. E. (2009). The almanac of American politics 2010 : the senators, the representatives and the governors : their records and election results, their states and districts. National Journal Group ; University Presses Marketing [distributor].

Barone, M., & McCutcheon, C. (2011). The almanac of American politics 2012 : the senators, the representatives and the governors : their record and elections results, their states and districts. University of Chicago Press. https://login.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/publicati on/54645?accountid=14677&decadeSelected=2020+-

+2029&yearSelected=2012&monthSelected=01&issueNameSelected=02012Y0 1Y01$232012

Barone, M. (2013). Almanac of American politics 2014. University of Chicago Press. https://login.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/publicati on/54645?accountid=14677&decadeSelected=2020+-+2029&yearSelected=2014&monthSelected=01&issueNameSelected=02014Y0 1Y01$232014

Carnes, Nicholas. 2016. Congressional Leadership and Social Status (CLASS) Dataset, Version 1.9 [computer file]. Durham, NC: Duke University. Available online from www.duke.edu/~nwc8/class.html.

Carnes, N. (2018). The Cash Ceiling: Why Only the Rich Run for Office–and What We Can Do about It. Princeton University Press.

Carnes, N. (2016) Why are there so few working-class people in political office? Evidence from state legislatures, Politics, Groups, and Identities, 4:1, 84-109, doi:10.1080/21565503.2015.1066689

Carnes, N. (2013). White-collar government: The hidden role of class in economic policy making. The University of Chicago Press.

Carnes, N. (2012). Does the Numerical Underrepresentation of the Working Class in Congress Matter? Legislative Studies Quarterly, 37(1), 5–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41719830

Clymer, Adam. “Daughter of Slavery Hushes Senate.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 23 July 1993, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/07/23/us/daughter-of slavery-hushes-senate.html.

Cohen, R. E., Barnes, J. A., Cook, C., Barone, M., Jacobson, L., & Peck, L. F. (2019). The almanac of American politics : members of Congress and governors: their profiles and election results, their states and districts. Columbia Books & Information Services, National Journal. https://login.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/publicati on/54645?accountid=14677&decadeSelected=2020+-+2029&yearSelected=2020&monthSelected=01&issueNameSelected=02020Y0 1Y01$232020

Cohen, R. E., Barnes, J. A., Cook, C., Barone, M., Jacobson, L., & Peck, L. F. (2017). The Almanac of American Politics 2018 : members of Congress and governors: their profiles and election results, their states and districts. Columbia Books &

Information Services : National Journal. https://www.proquest.com/publication/54645?OpenUrlRefId=info:xri/sid:primo &accountid=14677&parentSessionId=3ZlPEsgZ%2Ff72nMVo7ZR6SrQOsaEl% 2BB3YwGqGBkDjnPU%3D&decadeSelected=2020%20-%202029&yearSelected=2018&monthSelected=01&issueNameSelected=02018 Y01Y01%24232018

Cohen, R. E., Barnes, J. A., Holland, K., Cook, C., Barone, M., Jacobson, L., & Peck, L. (2015). The almanac of American politics 2016 : members of Congress and governors: their profiles and election results, their states and districts. Columbia Books & Information Services (CBIS) ; National Journal. https://login.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/publicati on/54645?accountid=14677&decadeSelected=2020+-+2029&yearSelected=2016&monthSelected=01&issueNameSelected=02016Y0 1Y01$232016

Cohen, R. E., Cook, C. E., & Barone, M. (2021). The almanac of American politics 2022 : members of Congress and governors: their profiles and election results, their districts and states (Commemorative edition). Columbia Books & Information Services, National Journal. https://login.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/publicati on/54645?accountid=14677&decadeSelected=2020+-+2029&yearSelected=null&monthSelected=01&issueNameSelected=$B

Collins, L. M., & Bates, S. (2023, June 5). Who are the working class and how will they vote in 2024?. Deseret News. https://www.deseret.com/2023/6/4/23735084/who-are-the- working-class-voting-2024/

Congressional Quarterly. (2018, December 5). Member Fact Sheet [114th Congress]. CQ. https://plus.cq.com/report/53664?6

Congressional Quarterly. (2018a, November 12). CQ Guide to the 116th Congress. CQ. Congressional Quarterly. (2020, December 9). CQ Guide to the 117th Congress. CQ. Congressional Quarterly. (2023, February 16). Member Fact Sheet [115th Congress]. CQ. Congressional Quarterly. (2023, January 17). Member Fact Sheet [118th Congress]. CQ.https://plus.cq.com/report/78592?2

Cook Political Report. (2024). The cook partisan voting index (Cook PVISM). The Cook Political Report With Amy Walter. https://www.cookpolitical.com/cook-pvi

Crenshaw, K. (1998). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics.

Feminism And Politics, 314–343. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198782063.003.0016

Fleck, A. (2023, August 25). Infographic: The number of millionaires has skyrocketed. Statista Daily Data. https://www.statista.com/chart/30671/number-of-millionaires and-share-of-the-population/

Francia, P. (2012). Do Unions Still Matter in U.S. Elections? Assessing Labor’s Political Power and Significance. The Forum, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/1540- 8884.1497 Gallup. (2023, August 17). Congress and the public. Gallup.com. https://news.gallup.com/poll/1600/congress-public.aspx

Hayes, M., & Hibbing, M. V. (2017). The Symbolic Benefits of Descriptive and Substantive Representation. Political Behavior, 39(1), 31–50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48693868

Hoyt, C. L., & DeShields, B. H. (2020). How social‐class background influences perceptions of political leaders. Political Psychology, 42(2), 239–263.https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12697

Jones, P. E. (2016). Constituents’ Responses to Descriptive and Substantive Representation in Congress. Social Science Quarterly, 97(3), 682–698. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26612345

Kane, C. (2023, January 20). George Santos: Same-sex parents undermine the family unit. Los Angeles Blade: LGBTQ News, Rights, Politics, Entertainment. https://www.losangelesblade.com/2023/01/20/george-santos-same-sex-parents undermine-the-family-unit/

Kasperkevic, J. (2015, January 9). Poor Americans are less likely to vote and more likely to distrust government, study shows. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/money/us-money-blog/2015/jan/09/poor-americans-are- less-likely-to-vote-and-more-likely-to-distrust-government-study-shows

Makse, T. (2019). Professional Backgrounds in State Legislatures, 1993‐2012. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 19(3), 312-333. doi:10.1177/1532440019826065

Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? Contingent “Yes.” The Journal of Politics, 61(3), 628–657. https://doi.org/10.2307/2647821

Mayhew. (1974). Congress : The Electoral Connection.

Oh, I. (2015, June 23). Watch the first black woman who served in the US senate go off on the Confederate Flag. Mother Jones. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/06/carol-moseley-braun-confederateflag-video/.

Phillips, A. (2012). Representation and Inclusion. Politics & Gender, 8(4), 512-518. doi:10.1017/S1743923X12000529

Rowell, A., & Madland, D. (2024, April 15). The working-class push for progressive economic policies. Center for American Progress Action. https://www.americanprogressaction.org/article/working-class-push-progressive- economic- policies/#:~:text=Data%20from%20the%20ANES%20found,support%20raising%20the%20minimum%20wage.&text=Black%20and%20Hispanic%20members%20of%20the%20working%20class%20show%20even,increasing%20the%20m inimum%20wage%2C%20respectively.

Schaeffer, K. (2023, February 7). The changing face of congress in 8 charts. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/02/07/the- changing-face-of congress/#:~:text=Despite%20this%20growing%20racial%20and,at%20an%20a ll%2 Dtime% 20high.

Stevens, M. (2020, August 11). Poorer Americans have much lower voting rates in national elections than the nonpoor, a study finds. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/11/us/politics/poorer-americans-have-much- lower voting-rates-in-national-elections-than-the-nonpoor-a-study-finds.html

UCLA Department of Political Science. (2024a). UCLA presents Voteview.com beta. Voteview. https://voteview.com/data