College of Humanities

41 Picking Your Partner: an Exploration into the Heterosexual Matrix in the Dating Simulator Genre

Chris Jun

Faculty Mentor: Allison Segal (Writing & Rhetoric, University of Utah, Asia Campus)

Interactive possibilities and choices within digital art give audiences the ability to actively participate within its environment. In particular to video games, the player explores and performs actions that change the game’s NPCs, digital environment, and player avatars. These player actions are realized within the environment that fulfill desires or fantasies that shape their avatar’s identity or their experience in play. For this reason, analyzing player actions that influence interactive possibilities and choices within games are deeply exploratory into categories of identities (races, genders, disabilities, sexualities). As players’ interactions shape the digital environment, player actions can perform categories of identity, especially of queerness and gender. A player can choose to perform their interpretation of gender based on interactions with their romantic partner. Utilizing Judith Butler’s theories on the “heterosexual matrix” and “gender performativity,” the digital environments of dating simulators are analyzed to argue the instability of player avatar genders wherein the heterosexual matrix does not create interpretive genders for player avatars but instead interpretive player actions within gameplay loops distinguish gender from the avatar’s unstable gender.

Judith Butler, in her seminal book Gender Trouble, argues that current culture, society, and community efforts enforce a “heterosexual matrix” that promotes heterosexual and gender normativity. Explained through her biting critiques of other theories’s expressions on sex’s relation to gender, Judith posits and defines her theory of the matrix as:

“[…] that grid of cultural intelligibility through which bodies, genders, and desires are naturalized… to characterize a hegemonic discursive/epistemic model of gender intelligibility that assumes that for bodies to cohere and make sense there must be a stable sex expressed through a stable gender (masculine expresses male, feminine expresses female) that is oppositionally and hierarchically defined through the compulsory practice of heterosexuality.” (Butler, 1983)

Here, Butler suggests that in both rational assumptions (epistemic) and a wide range of concepts (discursive), the heterosexual matrix establishes a “stable sex expressed through a stable gender.” For example, under an epistemic and discursive viewing of a person whose physiology is presumably a male and whose performance aligns with masculine performant concepts, the gender of that person must be male. The same person viewed as not a strict understanding of both masculine physiology and performances, however, is understood as the opposite. That person’s gender is unstable. This is what Butler establishes to be a consequent binary between “stable sex” through a “stable gender” and unstable sex expressed through unstable gender. These binary views within the matrix are addressed to be problematic of heterosexual and gendered normativities. Afterall, if a stable gender is preferred over an unstable gender, it becomes socially wrongful for a person within the heterosexual matrix to be instably gendered. Therefore the matrix enforces heteronormative sexualities that then exert expressions of normative male and female genders.

It is pertinent that, as the paper will explore, video game environments do lack the regulatory structures in such digital environments. Most video game player avatars and NPCs discursively or epistemically lack regulatory structures to establish heterosexual matrixes. This matrix is utilized by Butler to critique our environment’s understanding on gender, and so videogames, as a product of our understandings of gender, are interpretively explorational for whether they conform or contradict the matrix. To this effect, this paper will focus on aspects of the discursive and epistemic structures. The first, how do video game environments understand gendered romances within a vanishingly absent discursive structure. The second, how do indeterminate sexes within epistemic structures become interpretive based on the player’s avatar and gender performances.

Alongside the release of early Nintendo video games, the 90’s Japanese game production and distribution markets initially created the dating simulator genre. Later, foreign markets, using and subverting standard game structures of Japanese dating sims, nurtured the growth of the genre and the digital environments that influence player actions. One of the touchstone games of these Japanese dating sims, specifically under the popular bishoujo (beautiful girl) subgenre, was Tenshitachi no Gogo (1985). Simulating the dating experiences of an unnamed male-orientated player whose goal is to “seduce [the bishoujo] in the tennis club, by befriending and gathering information from her friends” (Enloade, 2019), Tenshitachi no Gogo (1985)’s digital environment focused on interactions with the NPC bishoujo through a menu-based system that feature multiple reactions or questions. This became a hit. Bishoujo games and other dating simulator subgenres (Otome, Yaoi, and Yuri) structured their digital environments after Tenshitachi no Gogo’s and expanded on the different sexualities and genders that players were able to romance. Players were able to explore and experience more diverse possibilities through these expanded subgenres and choices. In short, new subgenres within the Japanese market expanded player actions as a result of Tenshitachi no Gogo (1985). This touchstone game’s structure, or gameplay loop, set the future of modern dating sim structures and how they would change and subvert it.

It is therefore necessary to understand this change and subversion by first briefly explaining gameplay loops in dating sims. Gameplay loops, also known as compulsion loops, are any repetitive cycles that are designed to provide engagement to the player. They are a principle of four different structures that analyze how player actions are transformed to a realization of the player’s desires or fantasies. In a graph created to explain this concept, Daniel Cook expresses this as such:

“The player starts with a mental model that prompts them to apply an action to the game system and in return receives feedback that updates their mental model and starts the loop all over again. Or kicks off a new loop.” (Cook, 2012).

Figure 1: A visual of Daniel Cook’s “Gameplay Loop” graph explaining a mental model that prompts a player action to be transformed into player feedback.

Figure 1: A visual of Daniel Cook’s “Gameplay Loop” graph explaining a mental model that prompts a player action to be transformed into player feedback.

Gameplay loops thus point toward a four structure environment in video games: Model, Action, Rules, and Feedback. Applying this to standard dating simulator environments: Model is the romance option and the player’s desire for their affection; Action is the interactive menu choices of questions or responses; Rules are the game system’s pre-scripted parameters; Feedback is the realization or reward from the player’s action. These standard dating simulator environments are dominant in many iterative titles. But as the dating simulator began new production in different markets, Model and Feedback structures were dissimilar to their Japanese counterparts. Hatoful Boyfriend (2011) is an early example of these new dating sims. In a strange interpretation of the genre, Hatoful Boyfriend (2011) is a dating sim where “all of the [romantic partners] are birds but retain human speaking capabilities and common otome game personality tropes.” (Enloade, 2019). This early example thus profoundly changes the Model and Feedback structures of the dating sim. Model, although still a romance option that the player desires to achieve affection, is drastically altered to anthropomorphically speaking avians; Feedback, although still rewarding the romance option’s affection, is drastically altered as affection that’s unlike dating simulators prior to its release. Therein lies the new inspiration for Action structures and change in player actions from the new developments on Model and Feedback structures. From these alterations from the traditional dating simulator environment, the player’s actions to understand new mental models of avian partners and the feedback rewarded from their choices meaningfully changes. Hatoful Boyfriend (2011) would inspire these same changes in many different environments for other iterations of the genre: Doki Doki Literature Club! (2017), Heaven Will Be Mine (2018), and Class of 09’ (2021). Of the many games, the two dating simulators chosen for this analysis are Hades (2018) and Monster Prom (2018).

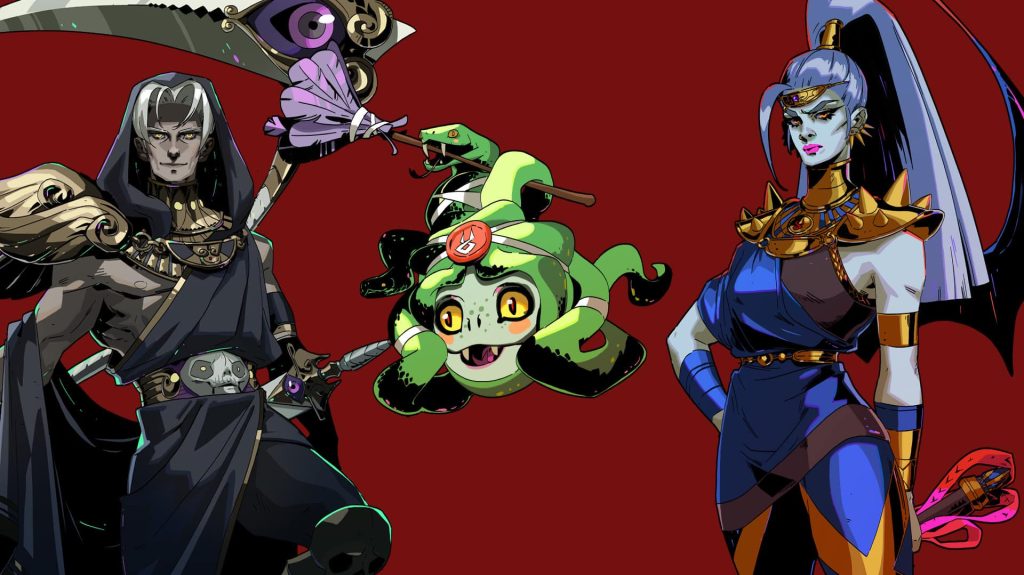

This first game, Hades (2018), explores the heterosexual matrix through the player avatar Zagreus’s unstable gender and his relationships with NPCs. Though the game denotes Zagreus’s epistemic male physiology, the game’s environment is absent of tacitly discursive structures and the epistemic physiologies of a select few NPCs. Therein player actions to romance NPCs in the dating simulator gameplay loop strongly distinguish Zagreus’s masculine and feminine gender performances despite his unstable gender. The gameplay loop’s Model and Feedback structure creates interactive player actions through investing gift items to target NPCs. The Model structure encourages the player to invest gift items (nectar and ambrosia) to earn a number of hearts with an NPC. The Feedback structure rewards Zagreus’s progression with the NPC’s relationship. Between these two structures, players engage with the game’s Action structures: choosing investments in relationships with target NPCs. Moreover, Model structures in the game’s environment have heterosexual or homosexual relationships between its many NPCs. Hades and Persephone, Achilles and Patroclus, Orpheus andEurydice each represent straight, gay, lesbian relationships that the player can then mimic from Model structures and understand discursive sexualities. Mimicking this, player actions to romantically involve themselves in a heterosexual or homosexual relationship are wherein discursively masculine and feminine gender performances can be interpretively understood. Therefore, the three romantic relationships Thanatos, Dusa, and Megaera are most significant in the player avatar Zagreus’s gender performances and therefore their unstable gender identity.

Figure 2: A triptych of Hades (2018)’s three romantic partners: Thanatos, Dusa, and Megaera.

Figure 2: A triptych of Hades (2018)’s three romantic partners: Thanatos, Dusa, and Megaera.

The male-romantic and female-romantic relationships from investments to romance with Thanatos or Maegera distinguish Zagreus’s sexuality. Other than romantic relationships established between NPCs, other discursive representations of masculine and feminine are vanishingly represented in the game’s coding, writing, or social structures. Normally, tacit associations with masculine or feminine performances are key in discursive structures. For example, certain actions of strength, endurance, and charisma are often understood to be tacitly masculine. In Hades (2018)’s game environment, however, many of these tacit actions are shared between both genders. Maegera is a fair example of this: (1) her strength and endurance is shown as an early boss in the Zagreous’s playthrough and (2) her charismatic approaches towards Zagreus are described as “competitive” and “dominatrix[-like]” as the player chooses actions to invest in her relationship. With this understanding that tacit discursive associations are shared rather than distinguished, the decision with either character discursively accentuates as the player can either choose to be romantically bonded with either or both characters. The player and their actions romancing Thanatos, Megaera, or both, interpret Zagreus’ sexuality from an otherwise instably gendered identity in accordance to the heterosexual matrix model.

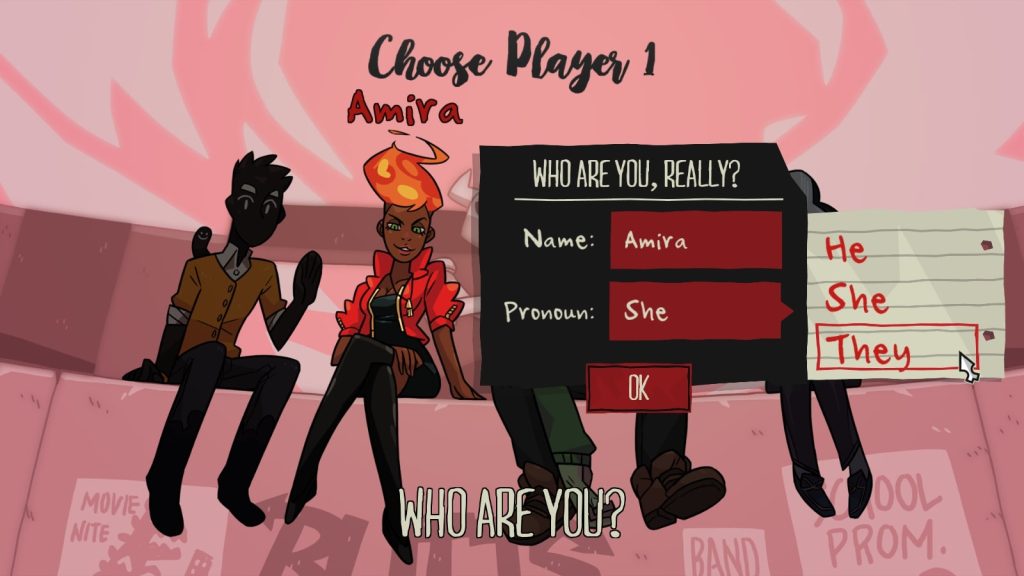

It is also important to note Zagreus’s romantic relationship with Dusa. The disembodied floating head of Medusa is an unstably gendered romance option with an unconventional romantic relationship. In the exploration of twenty two relationships between Zagreus and NPCs, Dusa is one of the few characters with no epistemic physiological sex. With no primary or secondary sex traits make Dusa the game’s only physiologically indeterminate romance option. Player actions to invest in this romantic relationship are transgressive in the models of a heterosexual matrix and more fruitfully explored in the second game analyzed in this paper: Monster Prom (2018). Developed by game studio Beautiful Glitch, The Monster Prom franchise is a series of multiple games that explore fictional monster player avatars romancing other fictional monster NPCs. Their first game Monster Prom (2018) is exploratory into monster romances and how their game environment lacks epistemic understandings of sex characteristics. Again, this gameplay loop is structured similarly to most traditional dating sim environments, but one interesting change is the Feedback structure. In the character selection menu, players can choose to alter the playable character’s name, pronouns, and therefore identity. This change intends to present these characters to be inclusive to the player’s choice of identity and provide an environment where sex doesn’t determine gender. A physiological female sex monster, for example, can be played as a character with a male name, male pronouns, and therefore male gender identity. Otherwise, the game’s Model, Action, and Rules systems don’t differ from the actions possible for every playable character. This arguably could be understood as a lack of a discursive structure —a dating simulator with a fully absent heterosexual matrix— but many other examples of masculine and feminine traits are represented in the player avatar’s expressions and NPC characters unlike Hades. Epistemically, however, referring to an epistemically female character with a male name and pronouns shows that monsters do not identify with their epistemic natures. Likewise, the epistemic models of this game are found to be undeniably loosely-based on the indeterminate sex of Oz, a playable player avatar who’s character expressions are also interpretable based on the feedback of the player’s actions.

Figure 3: screengrab of Monster Prom (2018)’s character selection menu

Figure 3: screengrab of Monster Prom (2018)’s character selection menu

Monsters in this game are diverse, but, for the focus of this analysis, are centered on playable characters and identity performed by their actions. From a first glance, the epistemologies of the player characters’ sexes are roughly determinate with the character’s physiologies except one. Whereas the one Frankenstein-like monster has a distinct masculine bulkiness and the two Frankenstein’s bride-like and genie monsters have distinct feminine slenderness, Oz is distinctly identified in-game as an “indeterminate sex.” His epistemology as a “body [created from] singular phobias” not only makes the monsters in the game understood under a loose epistemic structure, but also allows players to interpret Oz’s gender performances from the feedback from their player actions. As the game functions with the Feedback structure responses of Oz performing actions based on player actions, this indeterminate sex is able to perform indeterminate performances. The player actions to dance, study, play dodgeball, practice acting, and clean toilets are represented in Oz engaging in these activities wherein players are more free to interpret Oz’s expressions as feminine, masculine, or neither. Thus, making the epistemic model mostly absent from the game’s heterosexual matrix allows for the player to be more interpretive of Oz’s gender performances. Understanding this, it could be extended that all monsters are free to be indeterminate sexes. Afterall, even though many of these monsters have a distinct physiologies from the art shown, epistemic understandings may not be developed within this game environment with such characters as Oz and the plurality of monsters without epistemic sexes. It is therefore more interpretable to understand the gender of the player avatar from the player’s actions rather than the heterosexual matrix model.

This paper began with a claim on the exploratory identity interpretations in digital environments and Judith Butler’s critiques of her heterosexual matrix. It’s for this reason that, without regulated discursive and epistemic structures of the matrix, dating simulators and other game environments are able to be analyzed by their player actions and gameplay loops. The two dating simulators Hades (2018) and Monster Prom (2018) are especially fruitful explorations of gender for their player avatars and gameplay loop structures that lack discursive and epistemic structures. Therefore, each gameplay is uniquely individualized. Player actions, instead, identify gender identities from an unstable gender. Choosing a partner in a dating simulator opens many different explorable identities. So, in your playthrough, what partner will you pick?

References

Butler, J. (1989). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

Cook, D. (2023, March 1). Loops and arcs. LOSTGARDEN. https://lostgarden.home.blog/2012/04/30/loops-and-arcs/

Doki Doki Literature Club! (PC version) [Video game]. (2017). Team Salvato.

Enloade, L. (2019, February 4). The quest for love: Dating sims over the years. Medium. https://medium.com/@tpeng3/the-quest-for-love-dating-sims-over-the-years-af5fd4e81ce5

Field, M. (2021) Class of 09’ (PC version) [Video game]. SBN3. Hades (PC version) [Video game]. (2018). SuperGiant Games.

Hart, A. (2020, September 29). Here are all the Hades romance options. Gayming Magazine. https://gaymingmag.com/2020/09/here-are-all-the-hades-romance-options/

Hatoful Boyfriend (PC version) [Video game]. (2011). PigeoNation Inc.

Heaven Will Be Mine (PC version) [Video game]. (2018). Worst Girls Games. Monster Prom (PC version) [Video game]. (2018). Those Awesome Guys.

Super Metroid (SNES version) [Video game]. (1994). Nintendo.