College of Social and Behavioral Science

151 Examining Maternal Emotional Dysregulation Associated with Variability in Infans’ RSA Responses to the Still Face Paradigm at the Home Versus the Lab

Amanda Holt and Lee Raby

Faculty Mentor: Lee Raby (Psychology, University of Utah)

Background

The Still Face Paradigm (SFP) is designed to study how infants contribute to social interactions, especially how mothers and infants work together to regulate the infant’s negative emotions (Tronick et al., 1978). The SFP consists of three episodes lasting two minutes each. In the first episode, the mother is instructed to play with their infant as normal. In the second, the mother is instructed to maintain a blank facial expression and not engage with their infant. During the third episode, known as the reunion, normal interactions resume (Mesman et al., 2009). Most research using the SFP model has only been used to look at infant behavioral and physiological responsiveness. For example, a meta-analysis of over eighty empirical studies that used the SFP demonstrated that during the still-face, infants had reduced positiveaffect and gaze, increased negative affect, and that there was a carry-over of those affective states into the reunion episode (Mesman et al., 2009). Similarly, research has shown that infants in the SFP typically display increased physiological stress responses, including elevated heart rate and cortisol levels, as well as vagal regulation, which are indicators of stress (Moore et al., 2009). The Still-Face Paradigm (SFP) has been instrumental in developmental psychology research, shedding light on parent-infant interactions and early emotional development. This research tool has consistently unveiled a distinctive physiological response pattern in infants, marked by a significant reduction in Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA) during the still-face episode, followed by partial recovery during the reunion episode.

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) is a valuable tool developed to assess the various challenges individuals face in regulating their emotions effectively (Hallion et al., 2018). Comprising 36 items divided into six subscales, the DERS offers a comprehensive evaluation of emotion regulation difficulties. The first subscale, Nonacceptance of Emotional Responses, gauges individuals’ tendencies to resist or avoid their emotions rather than accepting and processing them constructively (Hallion et al., 2018). Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior assesses the extent to which emotions interfere with individual’s ability to stay focused andpursue their objectives. Impulse Control Difficulties highlight challenges in managing impulsive reactions triggered byintense emotions. Lack of Emotional Awareness measures individuals’ awareness and understanding of their emotional experiences (Hallion et al., 2018). Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies evaluates the availability and utilization of adaptive coping mechanisms. Lastly, Lack of Clarity of Emotional Responses assesses confusion or uncertainty regarding emotions. By identifying specific areas of difficulty, the DERS facilitates tailored interventions aimed at enhancing emotion regulation skills (Hallion et al., 2018).

Research suggests that parental emotional regulation plays a role in shaping the infant’s emotional development and regulatory abilities (Gao et al., 2022). Parents who have difficulties regulating their own emotions may struggle to provide consistent and responsive caregiving, which can impact the infant’s ability to regulate their own emotions effectively (Hallion et al., 2018). Infants may be sensitive to fluctuations in parental emotional expression, which can influence their physiological responses. In this context, the DERS could serve as a predictor of infant respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) in the Still Face Paradigm by indirectly reflecting the caregiver’s emotional regulation abilities (Gao et al., 2022). Caregivers who score high on the DERS, indicating greater difficulties in emotion regulation, may exhibitless consistent emotional responsiveness during the still face episode. This inconsistent responsiveness could potentially lead to greater fluctuations in the infant’s physiological arousal, including RSA (Gao et al., 2023). Caregivers with higher DERS scores may struggle to regulate their emotions potentially lead to greater fluctuations in the infant’s physiological arousal, including RSA (Gao et al., 2023). Specifically, caregivers with higher DERS scores may struggle to regulate their emotional expressions during the still face episode, leading to periods of heightened emotional arousal or disengagement that disrupt the infant’s regulatory processes (Gao et al., 2023). Infants may show altered patterns of RSA, reflecting fluctuations in their parasympathetic nervous system activity in response to these emotional dynamics (Gao et al., 2022).

These findings were primarily derived from controlled laboratory settings, offering insights into infant emotional regulation (Gao et al., 2023). However, the global onset of the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a seismicshift in the field of developmental psychology research, particularly in studies related to the SFP, maternal emotional regulation, and infant development (Mesman et al., 2009). The pandemic necessitated an abrupt transition to remote data collection methods, which challenged the established norms of in-person SFP studies (Tabachnick et al., 2022).Researchers were compelled to adapt their protocols, often guiding caregivers through video calls to administer the SFP at home. This adaptation introduced novel variables, such as potential distractions and caregiver compliance, which could affect the ecological validity of the results (Gao et al., 2023). Additionally, the closure of research facilities and laboratories during lockdowns disrupted ongoing SFP studies and impeded the initiation of new research projects. Experiments reliant on specialized equipment and controlled environments were put on hold, requiring researchers to develop alternative strategies to continue their work (Tabachnick et al., 2022). The pandemic also presented ethical dilemmas regarding the safety of research participants, particularly infants, and caregivers, and raised concerns about the risks associated with in-person data collection. Researchers had to balance the scientific value of their studies with the well-being of their subjects, all while adhering to physical distancing guidelines. The COVID-19 pandemic introduced new stressors, including health concerns, economic instability, and social isolation, which have had a significant impact on maternal emotional regulation (Gao et al., 2022). This emerging focus on maternal mental health as a critical variable in the SFP research exemplifies the need to account for the influence of caregiver emotional states on infant physiological responses and emotional development (Gao et al., 2022). Researchers have also faced the challenge of adapting their data collection and analysis methods to accommodate the specific limitations introduced by remote data collection (Tabachnick et al., 2022). These adjustments have been necessary to address the variability inherent in remote interactions, which differ markedly from the controlled laboratory conditions typically used in SFP studies (Gao et al., 2023). An emerging area of concern is the potential long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on infant development and caregiver-infant interactions. Researchers are increasingly investigating whether the stressors and changes in caregiving routines brought about by the pandemic might have enduring effects on child development and emotional regulation (Tabachnick et al., 2022).

Hypotheses

- Infants’ RSA responses to the Still-Face Paradigm will differ based on whether it was completed in the home versus the lab. Specifically, infants will exhibit a less pronounced reduction in RSA levels during the still-face episode when the Still-Face Paradigm is completed at home versus in the lab. Both groups ofinfants will exhibit partial recovery in RSA levels during the reunion episode.

- Maternal emotional dysregulation, measured using DERS, will be associated with infants’ RSA responses to the SFP regardless of whether the SFP was completed in the home versus in the lab. Specifically, infants of mothers with higher DERS scores will exhibit damped RSA reactivity during the still-face episode and minimal recovery during the reunion episode.

Design Plan

Study Type

Observational study

Blinding

No blinding is involved in this study.

This is an observational study so as a result, participants were not assigned to treatment conditions. However, researchers who were assisting with collecting the RSA data were unaware of the mothers’ DERS scores.

Study design

This study used data collected from a longitudinal study. Specifically, the study focused on RSA data from the Still Face Paradigm and DERS questionnaire responses collected when infants were approximately 7 months old.

Sampling Plan

Explanation of existing data:

Registration prior to analysis of the data: As of the date of submission, the data exists and I have accessed it, though no analysis has been conducted related to the research plan (including calculation of summary statistics). A common situation for this scenario when a large dataset exists that is used for many different studies over time, or when a dataset is randomly split into a sample for exploratory analyses, and the other section of data is reserved for later confirmatory data analysis. Separate files containing the variables that will be used in the current study have been created. However, summary statistics for the variables have not been examined yet. In addition, the data files have not yet been merged. Therefore, the research questions have not yet been answered using these data.

Data collection procedures:

7-month-old infants’ RSA levels were recorded during the 3 episodes of the Still Face Paradigm. 121 infants completed the visit in the lab and 66 completed it remotely from their homes. Mothers’ self- reported emotion dysregulation was measured using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale.

Sample size:

Participants will be included if the infant have usable RSA data as well as DERS questionnaire responses at the 7-month visit.

Sample size rationale:

The current study is using archival data. Therefore, the quantity of participants has been predetermined.

Variables

Manipulated variables:

No manipulated variables

Measured variables:

Predictors: maternal emotion dysregulation (DERS), at home vs lab experiment

Infant physiological stress reactivity (Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia), at home vs lab experiment.

Analysis Plan

Statistical model:

I ran a couple of repeated measures ANOVAs that included infant RSA during the three phases of the Still Face Paradigm (play, still-face, and reunion) as the outcome variable. To test my first hypothesis, the location of the Still Face Paradigm was included as a between-subjects variable. To test my second hypothesis, maternal emotional dysregulation was also entered as a continuous predictor of infant RSA outcomes.

Inference criteria:

For all analyses, a criterion of p < .05 (two-tailed test) will be used to determine if the results are significantly different from those expected if the null hypotheses were correct.

Data exclusion:

No data will be excluded.

Missing data:

Participants must have complete data for the variables used in the analyses.

Results

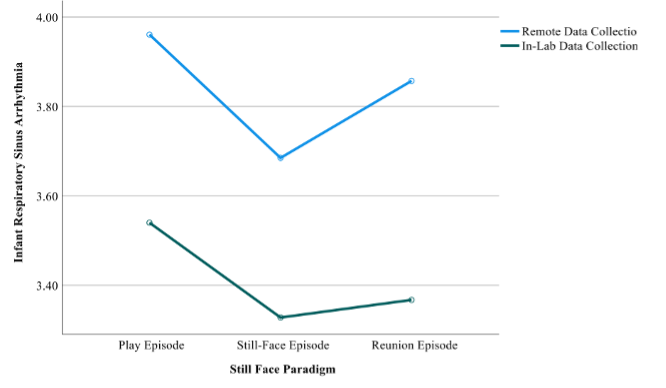

- A repeated measures ANOVA indicated that infants’ RSA levels exhibited quadratic changes during the StillFace Paradigm (p = .007) regardless of whether it was completed in the lab or the home.

- However, infants’ overall RSA levels were lower when the Still Face Paradigm was completed in the lab versus the home (p = .003)

- Maternal emotional dysregulation was not significantly associated with infants’ RSA levels, regardless of whether the SFP was conducted at home or in the lab.

Conclusion

- Contrary to our first hypothesis, infants RSA responses to the Still Face Paradigm did not differ based on whether the data were collected in the home versus the lab. In both contexts, infants’ RSA levels decreased during the still-face episode and then slightly increased during the reunion episode.

- However, infants did have higher RSA levels, indicative of increased parasympathetic activity, in their homes compared to the lab setting.

- Contrary to our second hypothesis, maternal emotional dysregulation was not associated with infant RSA responses to the Still-Face Paradigm.

Relevance to Society

Understanding how infants respond to stressors like the Still-Face Paradigm in different environments holds significant implications for parenting, childcare, and mental health support. By delving into how infants’ physiological responses are shaped by their surroundings, this research contributes to current data, aimed to enhance early childhood experiences and promote emotional regulation during stress inducing tasks.

References

Ablow, J. C., Marks, A. K., Feldman, S. S., & Huffman, L. C. (2013). Associations Between First-TimeExpectant Women’s Representations of Attachment and Their Physiological Reactivity to Infant Cry. Child Development, 84(4), 1373–1391. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12135

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129836

Gao, M., Saenz, C., Neff, D., Santana, M. L., Amici, J., Butner, J., … & Conradt, E. (2022). Bringing the laboratory into the home: A protocol for remote biobehavioral data collection in pregnant women with emotion dysregulation and their infants. Journal of health psychology, 27(11), 2644-2667.

Gao, M., Vlisides‐Henry, R. D., Kaliush, P. R., Thomas, L., Butner, J., Raby, K. L., & Crowell, S. E. (2023). Dynamicsof mother‐infant parasympathetic regulation during face‐to‐face interaction: The role of maternal emotion dysregulation. Psychophysiology, 60(6), e14248.

Hallion, L. S., Steinman, S. A., Tolin, D. F., & Diefenbach, G. J. (2018). Psychometric properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) and its short forms in adults with emotional disorders. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 539.

Jones-Mason, K., Alkon, A., Coccia, M., & Bush, N. R. (2018). Autonomic nervous system functioning assessed during the still-face paradigm: A meta-analysis and systematic review of methods, approach and findings. Developmental Review, 50, 113–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.06.002

Leerkes, E. M., Supple, A. J., O’Brien, M., Calkins, S. D., Haltigan, J. D., Wong, M. S., & Fortuna, K. (2014). Antecedents of Maternal Sensitivity During Distressing Tasks: Integrating Attachment, Social Information Processing, and Psychobiological Perspectives. Child Development, 86(1), 94–111.https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12288

Mesman, J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2009). The many faces of the Still-Face Paradigm: A review and meta-analysis. Developmental review, 29(2), 120-162.

Moore, G. A., Hill-Soderlund, A. L., Propper, C. B., Calkins, S. D., Mills-Koonce, R. W., & Cox, M. J. (2009). Mother-Infant Vagal Regulation in the Face-To-Face Still-Face Paradigm Is Moderated byMaternal Sensitivity. Child Development, 80(1), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01255.x

Philliber, S. G., & Graham, E. H. (1981). The impact of age of mother on mother-child interaction patterns. Journal of Marriage and Family, 43(1), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.2307/351421

Tabachnick, A. R., Sellers, T., Margolis, E., Labella, M., Neff, D., Crowell, S., … & Dozier, M. (2022). Adapting psychophysiological data collection for COVID‐19: The “virtual assessment” model. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43(1), 185-197.

Tronick, E., Brazelton, T. B., & Als, H. (1978). The structure of face-to-face interaction and its developmental functions. Sign Language Studies, (18), 1-16.