College of Social and Behavioral Science

142 Comparative Osteology of Canidae Species and Domestic Dogs in Nawthis Village

Auriana Dunn; Brian Codding; and Kathryn Sokolowski

Faculty Mentor: Brian Codding (Anthropology, University of Utah)

Abstract

The study of ancient animals can be very informative to the study of ancient people. In the case of Canidae species, this extends to domestic dogs, whose ancient uses provide insight into subsistence strategies and cultures of the associated human populations. However, the study of ancient Canidae species is difficult, as remains are often incomplete, and there are few postcranial differences between species. Previous studies focus on the differences in the crania and mandibles, with little emphasis on long bones or other body bones. My project examines four Canidae species and their postcranial differences. While some of the bones studied did not have any defining differences, the humeri and vertebrae of the domestic dogs show clear differences when compared to Canis lupus and Canis latrans. These differences must be substantiated to see if they are interspecies differences, or simply individual or breed differences. Mandibles were also compared, which emphasized already known differences. After the comparative osteology, the findings were applied to remains recovered from Nawthis Village, a Fremont site in the Great Basin. Using comparative osteology to determine specific species at archaeology sites is important for studying the environment and cultures of ancient peoples.

Keywords: comparative osteology, Canidae, domestic dogs, Fremont archaeology, zooarchaeology, Nawthis Village Site

Comparative Osteology of Canidae Species and Domestic Dogs in Nawthis Village Background Comparative Anatomy

Domestic dogs have been found at sites in North America, which date as far back as approximately ~9,900 years ago. The first domestic dogs likely came with humans dispersing from Asia (Ní Leathlobhair et al, 2018). Evidence from Fremont archaeological sites confirm the presence of domestic dogs in the Great Basin (Lupo et al, 1994). Studying these ancient domestic dogs is exceptionally difficult because there are few defining features that separate them from their canidae relatives, such as coyotes and foxes, which are also often found around Fremont sites. Additionally, few studies have been conducted on interspecies osteology of canids.

However, there are morphological differences in post-cranium canidae skeletons that could provide insight into differentiating them. Previous research has focused on vertebra shape (Martins et al, 2021) as well as long-bone anatomy (Bello et al, 2021). Others compare domestic dogs with wolves (Coli et al, 2023) as well as domestic dogs with coyotes (Calaway, 2001). That said, there is still wide interspecies variation that needs to be considered in osteology comparatives (O’Keefe et al, 2013).

Here, I outlined comparative anatomy between domestic dogs (Canis familiaris), coyotes (Canis latrans), wolves (Canis lupus) and foxes (Vulpes sp.) with specific focus on postcrania. Then, I applied this method to analyze canid remains from Nawthis village, a Fremont archaeological site in the Great Basin.

Nawthis Village Site

In 1976, the University of Utah Archaeology Center excavated at the Nawthis Village site, a Fremont village site occupied from 800 – 1150 AD. Nawthis Village has been dated to a period just before the Fremont people switched from agriculture, back to hunting and gathering (Coltrain et al, 2002). This switch is a unique one; for other groups, once hunter-gatherers begin agriculture, they stay agriculturists because agriculture can support large population sizes.

The Fremont people of the Great Salt Lake Basin and surrounding areas started to incorporate farming into their lifestyles ~1,500 years ago (Coltrain et al, 2002). After the shift back, the Fremont people dispersed and returned to reliance on wild food (Janetski, 1997).

Methods

This paper looks at the comparative osteology of five canid species. The specimens studied include bones from 12 specimens: three wolves (Canis lupus), three coyotes (Canis latrans), two domestic dogs (Canis familiaris), two red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), and one kit fox (Vulpes macrotus). The comparatives were conducted on four types of bones: mandibles, os coxae, humeri (posterior), and cervical vertebrae.

After the comparative was completed, the results were applied to canid remains found at the Nawthis Village site in central Utah. Those specimens include a partial humerus, a cervical vertebra, and an ilium of a juvenile canidae.

| Specimen # | Species | Part | AGE | Location | Museum | notes |

| UMNH.VP.34467 | Canis lupus | Mandible | ~500 yrs. | Owl Cave | NHMU | |

| UMNH.VP.34472 | Canis lupus | Left humerus | ~500 yrs. | Owl Cave | NHMU | |

| IMNH R–884 | Canis lupus | Skeleton | modern | unknown | IMNH | male |

| UMNH.VP.34471 | Canis

lupus |

Left

humerus |

~500 yrs. | Owl Cave | NHMU | |

| UMNH 31972 | Canis latrans | Skeleton | modern | Box Elder Co.

Lakeside |

NHMU | male |

| Catalog No. 012 | Canis latrans | Skeleton | modern | unknown | ZOOARCH LAB | |

| Catalog No. 006 | Canis

latrans |

Skeleton | modern | Lander Co.

NV |

ZOOARCH

LAB |

juvenile |

| Catalog No. 038 | Canis familiaris | Skeleton | modern | Yavapai Co. AZ | ZOOARCH LAB | |

| Catalog No.

29647 |

Canis

familiaris |

Skeleton | modern | Elko Co.

NV |

NHMU | |

| Catalog No. 29365 | Vulpes vulpes | Skeleton | modern | Salt Lake CO. UT | NHMU | |

| UMNH 32690 | Vulpes vulpes | Skeleton | modern | Salt Lake CO. UT | NHMU | |

| Catalog No.

29662 |

Vulpes

macrotus |

Skeleton | modern | unknown | NHMU |

Table 1. Specimens used in the comparative analysis. Specimens were borrowed from the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU), the University of Utah’s Zooarchaeology Lab (ZOOARCH LAB), and the Idaho Museum of Natural History.

| AD

Specimen # |

Field # | Part | Family | Recovered | Location |

| AD 33B | FL 7 33 | Cervical vertebra | Canidae | 1971 | Nawthis Village Site |

| AD 33C | FL 7 33 | Ilium | Canidae | 1971 | Nawthis Village Site |

| AD 33D | FL 7 33 | Humerus distal fragment | Canidae | 1971 | Nawthis Village Site |

Table 2. Canid remains recovered from Nawthis Village site near Fish Lake.

Results

Mandibles

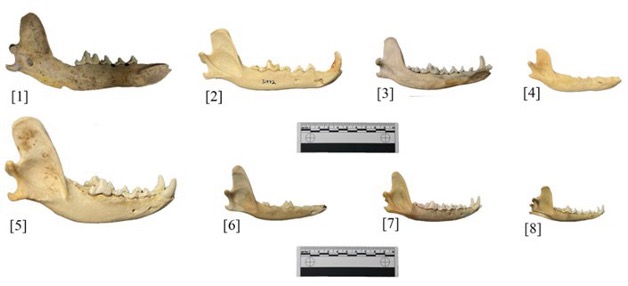

The domestic dog had the largest mandible of the group, which indicates that it is likely a larger breed. The domestic dog also shows slightly reduced prognathism when compared to the others. The rest of the jaws have similar overall shapes, the main variation between them being the angle and breadth of the mandibular ramus, where the mandible articulates with the cranium. The domestic dog mandible (Fig. 1 [5]) has a longer ramus from top to bottom, and a shallower angle between ramus and buccinator. While others, like the C. lupus are similar in size, they have sharper ramus angles. Additionally, the shape of the coronoid process is much wider in the domestic dogs. The process of C. latrans (Fig. 1 [2]) is also wider, while the rest of the specimens have processes that come to a distinct point. However, the main difference is the overall size of the jaws. The domestic dog is the largest, however this trait is known to vary amongst breeds.

Os coxae (right side view)

The shape of the iliac crests (ilium) is generally the same. However, the domestic dog specimen (Fig. 2 [4]), as well as the juvenile C. latrans (Fig. 2 [3]) and first V. vulpes (Fig. 2 [5]) are more ovular, while the rest are more circular. Additionally, the domestic dog ilium has an almost rectangular shape with a notch on the lower posterior side of the crest. The whole os coxae of the dog, and C. latrans are also narrower, with the pubic symphysis being out of view. This could be due to photograph angle, or something to do with specialization of the os coxae.

Os coxae (ventral view)

There are not many differences between the os coxae when looking at the ventral view. There are only slight variations in the angle of the iliac crests, the width between the iliac crests, and the width of the posterior (bottom of figure) side. For example, the Canis lupus specimen (Fig. 3, [1]) has iliac blades that flare outward, while the Canis latrans specimen (Fig. 3, [2]) has sharp upward turning points on the ischial tuberosity. These variations may be due to interspecies differences in daily activities. However, they may not be species specific; the differences may be due to natural variations between individuals.

The main determining difference between the os coxae is size, although that is harder to apply when considering different domestic dog breeds.

Humeri (Posterior view)

The primary difference between the various humeri is the size. The Canis familiaris humeri (Fig. 4, [5], [6]) are larger than all the other ones. This makes sense when considering that the domestic dog specimens are overall larger in size across all elements, likely due to them being large breeds. The first Canis latrans specimen is also larger; both wolf humeri (Fig. 4., [1][2]) are only slightly longer than the adult coyote humeri (Fig. 3, [3]). Additionally, the domestic dog humeri have much larger deltoid ridges, where the deltoid muscles would have attached. This could provide insight into the breeds of the dogs, and if they were used for heavy labor. The juvenile coyote humerus [4] is clearly unfused and missing the head and epicondyle.

Cervical Vertebra

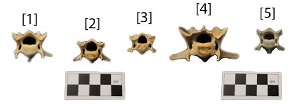

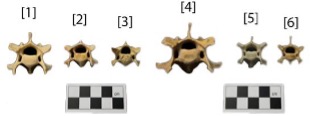

For each of the vertebrae specimens studied, I placed them into one of four categories depending on general shape. The vertebrae are grouped with others of a similar shape, and no vertebras from the same specimen are in the same category. There are only four groups as atlas and axis were not compared, and no specimen had complete sets of cervical vertebras, making differentiation between which cervical vertebrate was present, difficult. The vertebrae are oriented with dorsal side at the top of the figures.

Category one: Transverse processes (bottom flares) are the flattest and all are long and downward sloping. The prezygopophysis and postzygopophysis (top flares) are more angular with distinct points.

Category two: Transverse processes are more upturned, though not significantly, and have a slight bowl shape. They may simply be at a less downward angle than the category one vertebra. The dorsal sides have distinct spinous process and wider prezygopophysis and postzygopophysis.

Category three: The transverse processes are even more turned upward, and the spinous process is longer than those in category two.

Category four: Transverse processes have the most upturned angle, some having top points going straight upward. The processes also have two distinct points unlike the other categories. In many, the spinous process is the tallest of the vertebras associated with it.

In all instances the domestic dog vertebras are thicker with a wider breadth than the others. In categories three and four the domestic dog vertebras have transverse processes that flare outward farther than the tops of the vertebrae do. This is not the case with the other specimens, which have even flares. These differences may come from size, however, the one wolf vertebra (Fig. 8, [1]) does not have as flared of transverse processes despite being the largest vertebra of the group. Additionally, the domestic dog vertebrae have unusually thick spinous processes.

The wolf vertebra is significantly larger than any others. This could be due to the Idaho specimen (Fig. 8 [1]) simply being a larger wolf compared to the specimens from Owl Cave, or the fact that the C. latrans (UMNH 31972) is a male, and therefore would have larger long bones. It would be worthwhile to compare sizes between various wolves, as well as other dog breeds. Another notable feature is the slightly different size of the foramen between specimens. In the larger species, the domestic dogs and the wolf, the two cervical foramens are larger relative to the vertebral foramen. The smaller species, however, have larger vertebral foramen relative to the cervical foramens.

Nawthis Zooarchaeological Application

Cervical vertebra

The Nawthis canid vertebra (Fig. 9) looks the most like the category 4 vertebrae due to the upturned angle of the fragmented transverse processes.

The vertebra is close in size to the adult coyote specimens, and slightly larger than the fox specimens. It has unfused areas, such as between the body and spinous process, which substantiate this determination. The fact it is likely a juvenile makes other comparisons difficult.

It looks the most like a large canid due to the overall wide breadth and size, the breadth of the prezygopophysis and postzygopophysis, the breadth of the cervical foramens, as well as the relatively smaller vertebral foramen. However, I cannot infer transverse process size or breadth due to them being missing, so it is nearly impossible to assign it to a species.

Ilium:

This specimen (Fig. 10) is represented by an iliac blade. It is also likely a juvenile since the blade is unfused with the rest of the os coxae. The crest is generally a more ovular shape, like

C. latrans Catalog No. 006, domestic dog Catalog No. 29647, and V. vulpes Catalog No. 29365.

The rest of the crests, however, are more circular. This difference in morphology may not be species specific. It may be more indicative of use, or individual variation.

Humerus fragment:

This specimen (Fig. 11) is an unfused distal humerus. It has been assigned to the genus Canis due to the presence of olecranon foramen. There is not enough of the humerus to compare the morphology with the other canid species. The humerus is also likely a juvenile due to the humerus being unfused with the epicondyle. All the specimens, due to their association, similar age, and similar wear conditions, may have come from the same individual.

Discussion

Canidae species differentiation

In the comparisons, certain features were distinct between the specimens. In the humeri, the domestic dogs had distinct deltoid ridges that set them apart from the other specimens. In the cervical vertebrae, the domestic dogs had unique general shapes, which had little overlap with the shapes of the other vertebrae. These differences, though distinct, would need to be substantiated to define them as interspecies differences, as opposed to being produced by differences in size or breed morphologies. In the cases of the os coxae, there were no differences significant enough to differentiate the species.

Application at Nawthis Village

Applying the comparative findings to the Nawthis specimens did not garner any new insights. However, with further study it may be beneficial to future zooarchaeological findings. Canid species can inform researchers of past climatic and cultural conditions. If the remains found are confirmed to be domestic dogs, it could allow a glimpse into the lives of ancient people, in how they hunted, worked, or simply those they spent their company with. Not counting the specimens looked at in this study, there has been evidence of domestic dogs found at Fremont sites across the Great Basin. This evidence indicates that dogs were not used often, while some findings even indicate domestic dogs living separate from humans (Lupo et al, 1994). If the specimen I looked at, through later testing, is confirmed to be a domesticated dog, then this idea can be substantiated. The dog being found on its own, substantiates that the people nearby wouldn’t have many dogs. Additionally, the fact the dog is juvenile might indicate that few dogs were supported by humans so that they reached adulthood.

Conclusion

Differentiating domestic dogs from coyotes and wolves in the archaeological record remains an important endeavor for understanding past peoples. Comparative osteology tells us that there are morphological variations between canids, particularly in the crania, but even postcranially. However, there isn’t enough data in this present study to tell if this is interspecies variation, or simply variation between individuals or between different sexes.

Figure 1: Mandibles [1] UMNH.VP.34467, Canis Lupis [2] UMNH 31972, Canis latrans [3] Catalog No. 012, Canis latrans [4] Catalog No. 006, Canis latrans [5] Catalog No. 29647, Canis familiaris [6] Catalog No. 29365, Vulpes vulpes [7] UMNH 32690, Vulpes vulpes [8] Catalog No. 29662, Vulpes macrotus

Figure 2: Iliac crests [1] IMNH R —884, Canis lupus [2] UMNH 31972, Canis latrans [3] Catalog No. 012, Canis latrans [4] Catalog No. 29647, Canis familiaris [5] Catalog No. 29365, Vulpes vulpes [6] UMNH 32690, Vulpes vulpes [7] Catalog No. 29662, Vulpes macrotus

Figure 3: Pelvis, anterior [1] IMNH R—884, Canis lupus [2] UMNH 31972, Canis latrans [3] Catalog No. 29647, Canis familiaris [4] Catalog No. 29365, Vulpes vulpes [5] UMNH 32690, Vulpes vulpes [6] Catalog No. 29662, Vulpes macrotus

Figure 4: Humeri, posterior [1] UMNH.VP.34471, Canis lupus [2] UMNH.VP.34472, Canis lupus [3] UMNH 31972, Canis latrans [4] Catalog No. 006, Canis latrans [5] Catalog No. 038, Canis familiaris [6] Catalog No. 29647, Canis familiaris [7] Catalog No. 29365, Vulpes vulpes [8] UMNH 32690, Vulpes vulpes [9] Catalog No. 29662, Vulpes macrotus

Figure 5: Cervical vertebra, category one [1] UMNH 31972, Canis latrans [2] Catalog No. 012, Canis latrans [3] Catalog No. 006, Canis latrans [4] Catalog No. 29647, Canis familiaris [5] Catalog No. 29365, Vulpes vulpes

Figure 6: Cervical vertebra, category two [1] UMNH 31972, Canis latrans [2] Catalog No. 012, Canis latrans [3] Catalog No. 006, Canis latrans [4] Catalog No. 29647, Canis familiaris [5] Catalog No. 29365, Vulpes vulpes [6] UMNH 32690, Vulpes vulpes

Figure 7: Cervical vertebra, category three [1] UMNH 31972, Canis latrans [2] Catalog No. 006, Cantis latrans [3] Catalog No. 038, Canis familiaris [4] Catalog No. 29647, Canis familiaris [5] Catalog No. 29365, Vulpes vulpes [6] UMNH 32690, Vulpes vulpes [7] Catalog No. 29662, Vulpes macrotus

Figure 8: Cervical vertebra, category four [1] IMNH R—884, Canis lupus [2] UMNH 31972, Canis latrans [3] Catalog No. 006, Canis latrans [4] Catalog No. 038, Canis familiaris [5] Catalog No. 29647, Canis familiaris [6] Catalog No. 29365, Vulpes vulpes [7] UMNH 32690, Vulpes vulpes [8] Catalog No. 29662, Vulpes macrotus

Figure 9: Nawthis cervical vertebra

Figure 10: Nawthis ilium fragment

Figure 11: Nawthis distal humerus fragment

Works Cited

Bello, A., & Wamakko, H. H. (2021). Comparative anatomy of selected bones of forelimb of local Mongrelian Dog (Canis lupus familiaris) in Sokoto, Nigeria. Insights in Veterinary Science, 5(1), 026-031.

Calaway, M. (2001). A possible index to distinguish between Canis latrans and Canis familiaris. Coli, A., Prinetto, D., & Giannessi, E. (2023). Wolf and Dog: What Differences Exist? Anatomia, 2(1), 78–87.

Coltrain, J. B., & Leavitt, S. W. (2002). Climate and diet in Fremont prehistory: economic variability and abandonment of maize agriculture in the Great Salt Lake Basin. American Antiquity, 67(3), 453-485.

Janetski, J. C. (1997). Fremont hunting and resource intensification in the eastern Great Basin. Journal of Archaeological Science, 24(12), 1075-1088.

Lupo, K. D., & Janetski, J. C. (1994). Evidence of domesticated dogs and some related canids in the eastern Great Basin. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 199-220.

Martins, F. P., Souza, E. C., Bernardes, F. C. S., Abidu‐Figueiredo, M., Kasper, C. B., & de

Souza‐Junior, P. (2021). Anatomical variations in cervical vertebrae in two species of neotropical canids: What is the meaning?. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia, 50(1), 212-217.

Ní Leathlobhair, M., Perri, A. R., Irving-Pease, E. K., Witt, K. E., Linderholm, A., Haile, J., … & Frantz, L. A. (2018). The evolutionary history of dogs in the Americas. Science, 361(6397), 81-85.

O’Keefe, F. R., Meachen, J., Fet, E. V., & Brannick, A. (2013). Ecological determinants of clinal morphological variation in the cranium of the North American gray wolf. Journal of Mammalogy, 94(6), 1223-1236.