College of Health

30 Lifestyle Interventions, Physical Function, and Cancer Survivorship

Maren Curtis and Adriana Coletta

Faculty Mentor: Adriana Coletta (Health, Kinesiology, and Recreation, University of Utah)

Abstract

Introduction: Engagement in regular exercise is effective in improving physical function, and subsequently survival, among individuals living with and beyond cancer (i.e., a cancer survivor). Lifestyle (e.g., exercise and diet)interventions aimed at maximizing the benefits of the intervention to improve physical function are needed, especially among survivors on active treatment. Additionally, there is a gap in knowledge evaluating lifestyle interventions specifically for older cancer survivors (e.g., 2: 60 years) and the prevalence of older cancer survivors is growing.

Purpose: The purpose of this honors thesis project is to address the two aforementioned issues within the field of exercise oncology related to lifestyle interventions, physical function, and cancer survivorship. The first project will evaluate the feasibility of manipulating the time of day of exercise engagement on physical function among women with stage I-III breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. The second project will map the literature on the current stateof evidence related to lifestyle interventions aimed to improve physical function in older cancer survivors of all cancer types and stages.

Methods: Two studies were carried out, “A Scoping Review of Diet and Exercise Interventions on Function in Older Cancer Survivors” and “Feasibility of Manipulating Exercise Timing in Breast Cancer Survivors on Chemotherapy”(IRB number 00162526). The scoping review will search multiple databases and follow the PRISMA-scoping review extension guidelines to synthesize the literature related to the impact of exercise and/or diet interventions onphysical function in interventions exclusive to older cancer survivors. The second study aims to determine thefeasibility of assigning breast cancer patients on active treatment to exercise in a given time window, either themorning hours (5-10 am; AM group) or afternoon/evening hours (3-8 pm; PM group) for a 4-week intervention. For this project, I will carry out descriptive statistics in Excel to characterize the nutrient timing of these patients. This data will help inform the study design and intervention of the next, larger scaled trial.

Results: The scoping review found that one dietary intervention did not improve or maintain physical function. Another diet-only intervention was associated with the maintenance of physical function. Among 30 exercise-onlyinterventions, 22 improved physical function, five maintained it, one slowed the rate of functional decline, and twofound a decline regardless of the intervention. Among eight combined exercise and diet interventions, four improvedphysical function, three maintained physical function, and one found that exercise was positively associated with physical function and that physical function was inversely associated with symptom severity. The exercise timing feasibility study is still ongoing, but preliminary results pertaining to nutrient timing reveal that 13 of the 23 participants enrolled so far withdrew from the study. Ten of these were participant withdrawals, while three were withdrawn by the study. Six participants have completed the study so far. Self-reported data of their meal timing and sleep length during the study revealed a mean and median of 12 hours for weekday overnight fast (range: 9-15 hours). Their weekend overnight fast was a mean of 12.2 and a median of 12.5 (range 8-15 hours). Their weekday sleep length was a mean and median of nine hours (range 8- 11 hours). Their weekend sleep length was a mean of 10 hours and a median of nine hours (range 8-15 hours).

Introduction

Definitions

Cancer is a term for a group of genetic diseases in which body cells grow uncontrollably and spread to multiple parts of the body (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2022). Cells that are likely to replicate in this fashion are typically destroyed by the body’s immune system before they become cancerous. However, the body’s ability to eliminate potentially cancerous cells declines with age, which is part of the reason cancer is more prevalent in older adults (National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2021). Cancers are classified by their site of origin (typically an organ) and sometimes by the cell that formed them (NCI, 2021). Cancer survivor is a term for anyone with a history of cancer. It applies from diagnosis to the rest of a patient’s life, even if they are considered cancer-free (NCI, 2022). Lifestyle interventions are those which include dietary and/or exercise components. Their impacts on cancer will be explored in this paper.

Cancer Rates

International Data

The Global Cancer Observatory of the World Health Organization estimates there were approximately 19.3 million new cases of cancer globally in 2020 (Sung et al., 2021). The estimate of cancer incidence, or the number of new cases of cancer per year, is 222 cases per 100,000 people in 2020. There are disparities in international cancer incidence by sex and age. Females have an incidence rate of 186 per 100,000, while males’ cases are only 120.8 per 100,000. The most common cancer site for these new cases was breast, at 11.7% of all new cases, followed by lung (11.4%) and prostate (7.3%). It should be noted that although this data, from the Global Cancer Observatory of the World Health Organization, was published in 2020, the data is based on extrapolations from previous years and therefore was not impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic (Sung et al., 2021).

National Data

There are high rates of cancer incidence in the U.S. population. Although data is available up until the year 2020, U.S. cancer incidence rates were significantly impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic as lockdowns and restrictions reduced screenings and diagnoses (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program [SEER], 2023a). Therefore, this paper will use 2019 data for incidence rates and data from 2019 and earlier for prevalence rates, or the number of people alive with cancer. In 2019, the incidence rate for cancers of all sites in U.S. adults was 459.5 per 100,000 (SEER, 2023b). On January 1st, 2020, there were approximately 17.1 million U.S. adults living with cancer, which represents a prevalence rate of about 5,213 per 100,000 people (Population Reference Bureau [PRB], 2020; SEER, 2023b). The incidence of breast cancer in the U.S. in 2019 was 134.4 cases per 100,000, making it the most common cancer site in the country (SEER, 2023b).

Some demographics of adults have higher incidence rates than others. The rate among males in 2019 was 499.6 per 100,000, while female adults had a much lower rate of 433. Non Hispanic White Americans are the racial/ethnic group with the highest incidence (493.4) followed by Non-Hispanic Black (479.5) and Non-Hispanic American Indian/ Alaska Native (464.1). The racial/ethnic groups with the lowest incidence are Hispanic Americans of any race (371.1) and Non-Hispanic Asian / Pacific Islander Americans (324.6) (SEER, 2023b).

The most significant demographic discrepancy is age. The 2019 incidence rate for U.S. adults under 65 was 467.7 per 100,000 adults, while the rate for individuals 65 or older is 2036.6 per 100,000 adults (SEER, 2023b). In future years, the number of older cancer survivors in the U.S. is projected to increase to a prevalence of 2.4 million in 2040, up from 15.5 million in 2016 (Bluethmann et al., 2016). The growing population of cancer survivors over 65 warrants more research focused on interventions for this group.

The benefits of lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors

Higher levels of diet quality as measured by the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), a measure of diet quality, alternative Mediterranean Diet (aMED), and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) can reduce cancer mortality and all-cause mortality in cancer survivors (Park et al., 2022). Higher HEI scores have been associated with reduced cancer-related fatigue for breast cancer survivors (George et al., 2014).

Physical activity is beneficial for cancer survivors. It can improve treatment outcomes and reduce the risk of developing other cancers (NCI, 2023b; Patel et al., 2019). Studies have shown that engagement in exercise can reduce cancer cell proliferation and increase markers of apoptosis, or programmed cell death, which is one method by which the body combats cancer (Patel et al., 2019). Cancer survivors who are being treated for their cancer should continue to exercise, as physical activity is recommended during active cancer treatment by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (Ligibel et al., 2022).

Physical function, defined as physical mobility and the ability to perform basic daily tasks (Garber et al., 2010) is an important measure for cancer survivors. A 2015 study found that physical function as objectively measured by the short physical performance battery (SPPB) predicted cancer mortality, with each one-unit increase in SPBB score reducing mortality risk by 12% (Brown et al., 2015). Among cancer survivors 60 years or older, greater physical function reduces the risk of all-cause mortality by 55% (Ezzatvar et al., 2021).

Physical activity can improve physical function in cancer survivors. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) in a 2019 round table reviewed the evidence for the impact of physical activity on certain cancer outcomes (Campbell et al., 2019). To improve physical function, they found strong evidence that self-reported physical function in cancer survivors is significantly improved by moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, resistance training, or a combination of the two performed three times a week for 8-12 weeks (Campbell et al., 2019).

Along with exercising in general, particular attention to the time of day of exercise may serve utility in terms of the efficacy of the training to improve physical function. In a previous study of cancer survivors of all types, it was found that exercise taking place in the afternoon or evening hours (e.g., PM exercise) was associated with greater improvements in physical function as well as cardiorespiratory fitness and both upper and lower body muscular endurance (Coletta et al., 2021a). This is consistent with research in the general population that found that there is greater capacity for exercise during PM hours (Duglan & Lamia, 2019). Potential mechanisms to explain this relationship include natural diurnal fluctuations in body temperature and hormones that aid in muscle recovery after exercise (Coletta et al., 2021a; Duglan & Lamia, 2019; Ezagouri, et al, 2019; Gabriel & Zierath, 2019).

Needed interventions and research

Despite the benefits, 35.5% of adult U.S. cancer survivors in 2020 were not engaging in any physical activity. Female cancer survivors were even less active, with 37.7% being sedentary as compared to 33.2% of male survivors. A total of 41% of cancer survivors aged 65 and older did not engage in physical activity, as compared to 24.4% of survivors aged 18-44 and 29.1% of those 45 to 63. These are similar to the rates seen in the general U.S. population, which are 38% in those 65 and older, 27.3% in those 45-64, and 21.3% in those 18-44 (NCI, 2023b). Researchers clearly need to find creative ways to facilitate physical activity engagement in this population. Manipulating exercise timing could be a method to encourage exercise, while also promoting greater changes in outcomes important to survivors, such as physical function.

Manipulating exercise timing also has the advantage of being an easy recommendation for a physician to give to a patient, as it does not require the time or expertise involved in creating a detailed exercise prescription. Evaluating whether changing the time of day of exercise makes a meaningful difference in physical function and other treatment-related side-effects would result in a more efficient way to leverage the benefits of exercise and improve health outcomes in cancer patients. The exercise timing pilot study will address this gap, along with understanding nutrient timing of women living with breast cancer.

Along with this, considering the low engagement in physical activity among cancer survivors of all ages, increased prevalence of older cancer survivors, and the benefits of exercise (and other lifestyle interventions) to improve physical function, research is needed to understand how diet and exercise can improve physical function among older cancer survivors. To address this, we carried out a scoping review of the literature on the impact of lifestyle interventions on physical function among older cancer survivors.

Taken together, the purpose of this honors thesis project was to evaluate lifestyle interventions for cancer survivors of all ages and types of cancer on physical function. This was done by carrying out two studies: “A Scoping Review of Diet and Exercise Interventions on Function in Older Cancer Survivors” (Hardikar et al., 2024) and “Feasibility of Manipulating Exercise Timing in Breast Cancer Survivors on Chemotherapy” (Coletta et al., 2024).

Additionally, an analysis of dietary timing from data collected in the exercise timing study will also be conducted. The purpose of this analysis is to characterize nutrition timing for the patients participating in this study and provide information for a future, larger trial.

Methods

Scoping Review

The scoping review mapped the current literature on the impact of diet, exercise, or a combination of diet and exercise interventions on physical function in older cancer survivors (Coletta et al., 2022). Literature published by June of 2022 was compiled by searching multiple databases. The PRISMA-scoping review extension guidelines were followed for reporting results. There are five steps in this protocol: identifying the research question, identifying relevant articles, study selection, charting the data, and collating, summarizing, and reporting of results. Only randomized control trials and feasibility studies were included. Additionally, participants had to be 60 years or older with a cancer diagnosis but could be any gender and could be diagnosed with any cancer type or stage (Coletta et al., 2022). For this project, I screened articles for eligibility and extracted data from the articles. I also contributed to the manuscript by reviewing and providing feedback on drafts in preparation for submission to a peer-reviewed journal.

Exercise Timing Feasibility Study

The study’s main purpose was to determine the feasibility and acceptability of assigning breast cancer patients to either morning (AM) or afternoon/evening (PM) exercise for a 4-week exercise intervention. Secondary outcomes include evaluating the impact of the intervention on physical function and human performance and characterizing the meal and sleep timing of this patient population.

The exercise intervention used by the study was the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah’s (HCI) hospital-based exercise oncology program, called the Personal Optimism With Exercise Recovery (POWER) program (Coletta et al., 2021b). POWER consists of individualized exercise prescriptions of both aerobic and resistance training. The program also offers a variety of facilitation options to meet patients’ needs and preferences. They can choose to exercise in person at HCI, supervised from home via telehealth, or entirely unsupervised, following their exercise prescription in their own time (Coletta et al., 2021b). This flexibility is important to the many patients served by HCI who live very far away from Salt Lake City. This feasibility study used the standard POWER protocol for assessments and the telehealth delivery method for exercise training.

Participants were randomized to AM or PM exercise, with stratification for age (>/= 65 years), cancer stage, and hormone status, after enrolling in the trial. In the AM exercise group, workout start times had to fall between 5 am and 10 am. In the PM exercise group, workout start time had to fall between 3 pm and 8 pm. Exercise training was individualized for each participant based on an initial assessment that occurred at the start of the study. The same assessment was carried out at the end of the study. These assessments were part of standard POWER protocol and carried out by a physiatrist and exercise physiologist. Procedures in these assessments included the following physical function and human performance measures: cardiorespiratory fitness measured by either treadmill test or a 6-minute walk test, a timed up and go test, and a handgrip strength test. The resistance training was supervised via telehealth and was scheduled by the participants within their assigned time window. Participants chose their form of aerobic exercise and kept a detailed log of their exercise. Meal and sleep timing data were also collected in order to provide more information that will contribute to the design of a larger, future trial. These data were collected via the Ultra-Short Munich Chronotype Questionnaire and the Modified ACS Meal Timing Grid. For this project, I prescreened patient medical charts to determine eligibility for the trial. I also used data from the trial to conduct my diet timing analysis.

Results

Scoping Review

The review found only two studies that evaluated the effect of dietary interventions alone on physical function. One study found that increased calories and protein did not improve or maintain physical function in cancer survivors of many types. The other used high-dose vitamin D supplementation for 24-weeks in prostate cancer survivors in active treatment and found an association between the intervention and maintenance of physical function. The review found 30 studies that evaluated the effect of exercise interventions on physical function. 22 of the 30 observed an improvement in physical function, five found maintenance, one found a slowing in the rate of functional decline, and two found a decline regardless of the intervention. Eight of the studies evaluated by the review applied an intervention that involved both diet and exercise. Four studies found an improvement in physical function, three saw maintenance, and one found that exercise was positively associated with physical function and that physical function was inversely associated with symptom severity. We concluded that future research requires more adequately powered trials and more trials exclusive to older cancer survivors. We also identified a gap in trials examining the impact of diet and exercise in combination or diet alone on physical function in older cancer survivors (Hardikar et al., 2024).

Exercise Timing Feasibility Study and Diet Timing Analysis

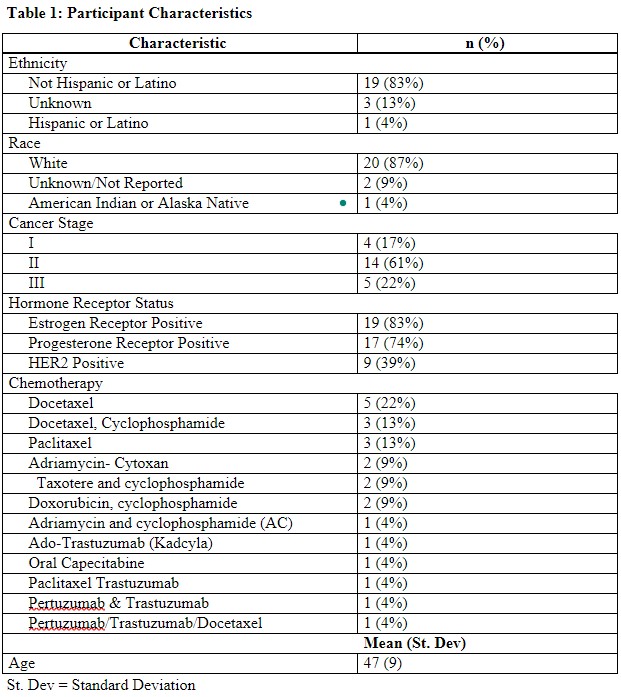

The Exercise Timing Feasibility Study is still ongoing. As of March 27, 2024, there are 23 participants enrolled in the study. The majority of participants are not Hispanic or Latino. At least 87% of the participants are white. The average age of the participants is 47, with a standard deviation of nine years (see Table 1).

Patients participating in the Exercise Timing Study had to be undergoing chemotherapy and be in the first half of their prescribed chemotherapy treatment. There was great variation in the type of chemotherapy participants were being treated with. The most common chemotherapy, which was being used to treat 22% of participants, was Docetaxel. The second most common treatment method was Docetaxel in combination with Cyclophosphamide, which was seen in 13% of participants (Table 1).

The majority of participants had stage II breast cancer, at 61%. Twenty-two percent were stage III, and 17% were stage I. There are different subtypes of breast cancer defined by their hormone receptor status. Of the 23 participants enrolled so far, 83% of participants are estrogen receptor positive, 74% are progesterone receptor positive, and 39% are HER2 Positive (Table 1).

Table 1: Participant Characteristics

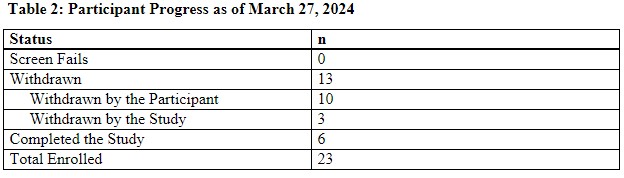

Of the 23 participants, there were no screen failures. Thirteen participants were withdrawn from the study. Ten participants chose to withdraw themselves, while three were withdrawn by the study team (Table 2). Of the 10 participants who withdrew, four withdrew due to other obligations such as work and family. Another four participants withdrew due to chemotherapy side effects. One participant withdrew due to a combination of weather impacting her ability to drive and her chemotherapy side effects. One participant withdrew due to difficulty scheduling telehealth exercise visits around her employment.

Of the three participants that were withdrawn by the study, two advanced beyond the halfway point of their prescribed chemotherapy, which made them ineligible for the study. The last participant was withdrawn due to a lack of response to the study team’s attempts to contact them. Six participants so far have completed the study (Table 2).

Table 2: Participant Progress as of March 27, 2024

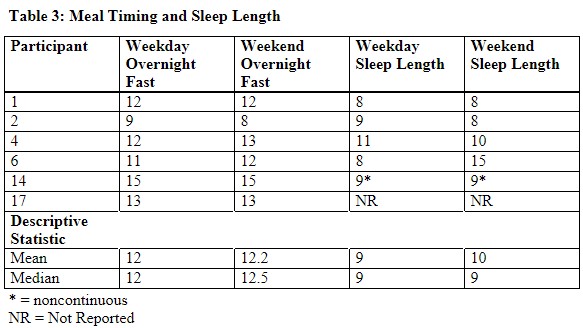

Among the six participants who have completed the trial thus far, a questionnaire about their sleep and meal timing behaviors during the 4-week intervention was administered at the end of the study. I analyzed their self-reported data on length of overnight fast and nightly sleep.

Overnight fast is the length of time between the last meal or snack consumed at night and the first meal or snack consumed the next day. For both overnight fast and sleep length, participants were asked to describe their typical timing on weekdays and on weekends. Their weekday overnight fast was an average of 12 hours and a median of 12 hours (range 9-15 hours). On weekends, they typically fasted slightly longer, with an average of 12.2 hours and a median of 12.5 hours (range 8-15 hours). Sleep length for weekdays was a mean and median of 9 hours (range: 8-11 hours). On weekends, they had similar results, with a mean length of 10 hours and a median length of nine hours (range 8-15 hours).

Discussion

Applications

Scoping Review

The vast majority of studies that involved a physical activity component improved physical function. This indicates that physical activity interventions are effective in improving physical function in older cancer survivors. Clinicians treating this population should prescribe exercise to their patients, and exercise oncology programs such as POWER should continue to operate and serve cancer survivors of all ages.

Feasibility Study and Diet Timing Analysis

Clinicians have limited time to make lifestyle recommendations to cancer survivors. There is value in having specific, uncomplicated recommendations that are proven to be effective in improving physical function, an important measure of quality of life. Manipulating meal and exercise timing, if proven to be effective, could be one of these simple and low -risk recommendations made by clinicians to improve treatment outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths and Limitations of Scoping Review

The review was meticulously conducted and relied on established protocols to conduct an effective literature search. However, the review had some weaknesses. It excluded many feasibility trials in the review which do not provide as conclusive evidence as randomized controlled trials. Articles in languages other than English were also excluded from this review. Finally, no quality assessment of the articles included was performed.

Strengths and Limitations of Feasibility Study and Diet Timing Analysis

The study so far has a low number of participants which makes it statistically underpowered. Additionally, the study is still ongoing, so any results are preliminary and could change with new data. Finally, meal timing and sleep length were only reported during the intervention. No baseline data was collected to determine typical sleep length or meal timing.

References

American Cancer Society (ACS). (2022, February 14). What is Cancer? https://www .cancer.org/cancer/understanding-cancer/what-is-cancer.html.

Brown, J.C., Harhay, M. 0., & Harhay, M. N. (2015). Physical function as a prognostic biomarker among cancer survivors. British journal of cancer, 112(1), 194-198. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.568

Bluethmann, S.M., Mariotto, A.B. & Rowland, J.H. (2016). Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence Trajectories and Comorbidity Burden among Older Cancer Survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 25(7). p. 1029-36

Campbell, K.L., Winters-Stone, K.M., Wiskemann, J., May, A.M., Scheartz, A.L., Courneya, K.S., Zucker, D.S., Matthews, C.E., Ligibel, J.A., Gerber, L.H, Morris, G.S., Patel, A.V., Hue, T.F., Perna, F.M., Scmitz, K.H. (2019, November). Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Round table.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 51(11):p 2375-2390, DOI: 10.1249/MSS.00000000000021 l 6

Coletta, A. M., Playdon, M. C., Baron, K. G., Wei, M., Kelley, K., Vaklavas, C., Beck, A., Buys,

S.S., Chipman, J., Ulrich, C. M., Walker, D., White, S., Oza, S., Zingg, R. W., & Hansen, P. A. (2021). The association between time-of-day of habitual exercise training and changes in relevant cancer health outcomes among cancer survivors. PloS one, 16(10), e0258135. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258135

Coletta, A. M., Rose, N. B., Johnson, A. F., Moxon, D.S., Trapp, S. K., Walker, D., White, S., Ulrich, C. M., Agarwal, N., Oza, S., Zingg, R. W., & Hansen, P.A. (2021). The impact of a hospital-based exercise oncology program on cancer treatment-related side effects among rural cancer survivors. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(8), 4663-4672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06010-5

Coletta, A. M., Hardikar, S., McFarland, M. M., Casucci, T., Ehlers, D., Dolgoy, N., Williams, G., & Poh Loh, K. (2022, July 1). Effects of Diet and Exercise Interventions on Physical Function in Older Adults with Cancer: A Scoping Review Protocol. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/r6ejn.

Coletta, A.M., Dunston, E., Curtis, M., Taylor, S., Chipman, J., Kristen, K., & Saviers-Steiger,

C. Feasibility of Manipulating Exercise Timing in Breast Cancer Survivors on Chemotherapy. (2024). Ongoing, IRB number 00162526. Clinical Trial Number NCT05821244.

Duglan, D., & Lamia, K. A. (2019). Clocking In, Working Out: Circadian Regulation of Exercise Physiology. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM, 30(6), 347-356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2019.04.003

Ezagouri, S., et al. (2019). Physiological and Molecular Dissection of Daily Variance in Exercise

Capacity. Cell Metab, 30(1): 78-91.e4.

Ezzatvar, Y., Ramirez-Velez, R., Saez de Asteasu, M. L., Martinez-Velilla, N., Zambom Ferraresi, F., Izquierdo, M., & Garcia-Hermosa, A. (2021). Physical Function and All Cause Mortality in Older Adults Diagnosed With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 76(8), 1447-1453. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa305

Gabriel, B.M. and J.R. Zierath, (2019). Circadian rhythms and exercise- re-setting the clock in metabolic disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 15: 197-206.

Garber, C.E., Greaney, M.L., Riebe, D. et al. (2010). Physical and mental health-related correlates of physical function in community dwelling older adults: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr 10, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-10-6

George, S. M., Alfano, C. M., Neuhauser, M. L., Smith, A. W., Baumgartner, R. N., Baumgartner, K. B., Bernstein, L., & Ballard-Barbash, R. (2014). Better postdiagnosis diet quality is associated with less cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors.

Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice, 8(4), 680-687. https://doi.org/10.1007/sl 1764-014-0381-3

Hardikar, S., Dunston, E., Winn, M., Winterton, C., Rana, A., Locastro M., Curtis, M., Mulibea,

P., Maslana, K., Kerschner, K., McFarland, M., Casucchi, T., Ehlers, D., Dolgoy, N., Williams, G., Poh Loh, K., Coletta, A. (2024). A Scoping Review of Diet and Exercise Interventions on Function in Older Cancer Survivors. Under review by the Journal of Geriatric Oncology.

Ligibel, J. A., Bohlke, K., May, A. M., Clinton, S. K., Demark-Wahnefried, W., Gilchrist, S. C., Irwin, M. L., Late, M., Mansfield, S., Marshall, T. F., Meyerhardt, J. A., Thomson, C. A., Wood, W. A., & Alfano, C. M. (2022). Exercise, Diet, and Weight Management During Cancer Treatment: ASCO Guideline. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 40(22), 2491-2507. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.00687

National Cancer Institute (NCI). (2021, October 11). What is Cancer? National Institutes of Health (NIH). https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer.

National Cancer Institute (NCI). (2022, November 17). Definitions. Office of Cancer Survivorship, National Institutes of Health (NIH) https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/definitions.

National Cancer Institute (NCI). (2023, July). Aging and Cancer. National Institutes of Health (NIH). https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/bbpsb/aging-and-cancer.

National Cancer Institute (NCI). (2023, August). Cancer Survivors and Physical Activity.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). https://progressreport.cancer.gov/after/physical_activity.

Park, S. Y., Kang, M., Shvetsov, Y. B., Setiawan, V. W., Boushey, C. J., Haiman, C. A., Wilkens, L. R., & Le Marchand, L. (2022). Diet quality and all-cause and cancer-specific mortality in cancer survivors and non-cancer individuals: the Multiethnic Cohort Study. European journal of nutrition, 61(2), 925-933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-02 l- 02700-2

Patel, A.V., Friedenreich, C.M., Moore, S.C., Hayes, S.C., Silver, J.K., Campbell, K. L., Winters-Stone, K., Gerber, L.H., George, S. M., Fulton, J.E., Denlinger, C., Morris, G. S., Huge, T., Schmitz, K. H., Matthews, C. E. (2019, November). American College of Sports Medicine Round table Report on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and

Cancer Prevention and Control. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 51(11):p 2391- 2402, DOI: 10.1249/MSS.00000000000021 l 7

Population Reference Bureau (PRB). (2020). U.S. Indicators: Total Population. https://www.prb.org/usdata/indicator/population/snapshot/.

Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 71(3), 209-249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER). (2023, May 17). Impact of COVID on 2020 SEER Cancer Incidence Data. Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute (NCI). https://seer.cancer.gov/data/covid-impact.html.

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER). (2023, November 16). SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics. Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute (NCI). https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics network/explorer/.