College of Fine Arts

24 Non-Objective and Subject Matter-Dependent Visual Stimuli In Artwork Therapy: Investigating Heart Rate Variability in Vunerable Populations

Pablo Cruz-Ayala

Faculty Mentor: John Erickson (Art & Art History, University of Utah)

Introduction

Individuals across cultures, countries, and communities are faced with daily stressors. These stressors, if left untreated, can lead to myriads of health-related conditions that negatively impact standards of living. Whether those individuals can maintain their mental and physical well-being is heavily connected to their ability to emotionally regulate (ER) [1]. Emotional regulation and stress-fighting resources are available to many individuals through health care, community support, and a general sense of psychological belonging [1,2]. Access to these systems allows individuals to have robust healthy reactions to challenges faced in life. Undocumented immigrants (UI) in the United States face many barriers to stress management care and thus require alternative accessible opportunities to better their ER.

As of 2019, Utah was home to approximately 89,000 UI. Immigrants in the United States face growing challenges that negatively impact their emotional and physical well-being daily [1]. Persistent stressors encountered by UI’s encompass a range of challenges; socioeconomic adversity, unstable living conditions, rigorous work demands, work abuse, social stigmatization, racial discrimination, deportation, and constrained access to social and public health services [2]. Systemic barriers undermine UI’s ability to improve and support their ER. Limited aid forces these populations to experience long- term health effects of isolation, stress, and mental illnesses without direct paths of accessible treatment [1, 2, 3]. Therefore, the possibility of integrating accessible therapies and ER-improving experience into publicly accessible spaces could be considered a valuable resource to strengthen an otherwise unsupported population.

This research aims to utilize a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to collect and interpret heart rate variability (HRV) data through a public program. HRV is defined as the root mean square variability of the time steps between individual heartbeats over a signal duration. Usually, heart rate signals are collected for the duration of treatment or stress-inducing stimulus. HRV samples for this research will be collected in two visual stimulus experience periods. Art that visualizes immigrant subject matter will be one stimulus, and abstract nonobjective artwork will function as a second stimulus. The HRV theory suggests that inducing rhythmic brain activity, along with increased heart rate oscillations, enhances functional connectivity in emotion regulation-related brain networks via the autonomic nervous system [5]. Heart rate patterns are induced via the sinoatrial/atrioventricular nodes and are further regulated by the sympathetic nervous system. Impulses have been linked to human innate stress reactions and longitudinal emotional regulation patterns. Where higher HRV values are linked to greater ER capabilities and lower HRV are associated with decreased ER capabilities. In this research study, the interactions between individuals’ connections with visual stimulus and their HRV and whether they benefit each other positively. Visual stimulus has yet to be explored to impact an individual’s HRV similarly to other physical therapies.

Previous CBPR has shown promise in fields like art therapy, environmental design, medicine, and studies involving similar at-risk population targets [1,2,6]. The community partners of this project felt that art exposure therapy offers potential insights into improving the mental health and cultural well- being of the UI populations in Salt Lake City. Demonstrating community value to explore how UI’s emotionally respond to immigrant subject matter vs abstract or nonrepresentational artwork. This study aims to link a positive HRV response to a stimulus that they positively identify and connect with increasing from a control no stimulus HRV expected value. A hypothesis this research hopes to test is if individuals who identify with the visual art stimulus show an improvement/increase in their HRV scores from the current accepted no-stimulus values. A positive increase in HRV would mean an improved autonomic nervous response to stress acutely and chronically [5]. Ultimately this would signify a way to create publicly accessible mental health treatments to better overall standards of living for individuals who struggle to access healthcare like UI individuals.

This study aims to address the research gap within Heart Rate Variability (HRV) implementation utilizing visual stimulus rather than physical art creation as well as subject matter significance. By analyzing visual stimulus/gallery experiences along with HRV, this research will contribute to a better understanding of HRV applications and limitations within public spaces. Ultimately this research aims to access a new model for accessible ER therapies and patient-specific treatments.

Background

Current ER research explores the benefits and connections of art-based therapies in conjunction with induced controlled stressors/stimuli on an individual’s treatment [4]. Historically, ER research explores emotional changes within individuals on the autism spectrum, children of abuse, and those with mental health disorders like trauma-induced depression [4]. ER can be physiologically and emotionally quantified through heart rate variability (HRV) analysis. This analysis is conducted via wearable electrocardiogram leads, pulse oximeters, or heart rate applications. HRV is defined as the root mean square variability of the time steps between individual heartbeats over some time. Usually, heart rate signals are collected for the duration of treatment or stress-inducing stimulus. The HRV theory suggests that inducing rhythmic brain activity, along with increased heart rate oscillations, enhances functional connectivity in emotion regulation-related brain networks via the autonomic nervous system [5]. Heart rate patterns are induced via the sinoatrial/atrioventricular nodes and is further regulated by the sympathetic nervous system. Impulses have been linked to human innate stress reactions and longitudinal emotional regulation patterns. Where higher HRV values are linked to greater ER capabilities and lower HRV are associated with decreased ER capabilities.

Art therapy is an interdisciplinary field that explores the therapeutic potential of individual or communal artistic expression in addressing psychological and emotional challenges. Grounded in both psychology and the arts, this modality can utilize various artistic mediums. Expressions such as painting, drawing, sculpture, music, self-expression, emotional processing, and overall mental well-being [8, 20]. The current gaps in art therapy require the exploration of the relationships between subject matter, visual stimulus, and public participation viability Art as therapy has gained recognition for its effectiveness in diverse clinical settings, Previous work has also focused on improved overall mental health in vulnerable patient populations like children who have traumatic events [14]. Interdisciplinary research initiatives have identified gaps in understanding arts engagement within public spaces [2]. A recent study involving a population sample of 470 individuals demonstrated positive experiences and increased social interactions associated with active engagement in various art forms [2]. This exploration, while focusing on older demographics with dementia, holds promising implications for broader utility in community engagement initiatives. While art therapy traditionally focuses on individual therapeutic interventions, its broader applications extend to public health contexts, where it can be harnessed to enhance community well-being and mental health via ER research.

CBPR was a key collaborative and action-oriented approach to this research that involved partnerships between researchers and community members. Encouraging future consideration and developments that incorporate the UI’s populations and community members impacted. CBPR has made developments to increase the number of vulnerable or at-risk populations in public health research to challenge health inequalities [23]. The needs assessment, design, and research intervention were tailored to meet community challenges and stressors discussed via community cohort meetings of UI’s [3, 23]. This approach helps ensure that this research benefits the communities it intends to serve and promotes equitable and sustainable solutions to societal challenges that are too complex to address immediately.

The concept of public space psychological development refers to how individuals’ mental and emotional well-being is influenced and shaped by their interactions with public spaces and environments [13, 15, 19, 20]. Public spaces encompass a wide range of environments, from parks and urban plazas to museums and health centers. These spaces serve as platforms for social interactions, community engagement, and personal growth [19, 20]. Space development reaches into every facet of people’s day- to-day lives. Whether that is in the advertisements in public transportation, the concrete infrastructure of office spaces, or even the art displayed in clinical waiting rooms. Understanding public space psychological development is crucial for creating inclusive, supportive, and mentally enriching public spaces that contribute positively to individuals’ overall well-being.

Through preliminary community insights, we recognized gallery settings as ideal environments capable of fostering inclusivity, amplifying voices, and cultivating a more comprehensive understanding of cultural heritage. Gallery spaces possess the unique ability to invite marginalized communities to engage in discussion and shared experiences [14, 16, 18, 20]. This research project was driven by the desire to transform a public space into a platform that not only acknowledged but also elevated the narratives, art, and contributions of the surrounding UI communities in Salt Lake City. With the invaluable support of the Salt Lake City Arts Council, Finch Lane Gallery emerged as the perfect home for this project, offering a free, accessible space for community participants to engage with this research project.

Within this community-centric art space, we employed pulse oximetry in wearable finger devices as a primary electrocardiogram signal collector. Pulse oximetry stands out as a medical technology that seamlessly measures oxygen saturation levels in the blood along with heart rate signals. Wearable data- collecting devices are used as a non-invasive method and are widely utilized in healthcare settings. Wearable systems, at times, rely on reflectance readings that may be influenced by heart rate, skin tone, and uncontrollable parameters, necessitating careful consideration in later research methods and discussions to ensure the accuracy and validity of the collected physiological data.

For this research project, two fundamental categories of art need to be defined for visual stimulus. Objective and non-objective artworks. Objective artwork, represented tangible and recognizable cultural subject matter, providing viewers with identifiable imagery or content related to the undocumented immigrant experience. In contrast, non-objective artwork/ abstract/non-representational art diverges from concrete depictions to focus on color, form, and value. Non-objective artwork served as a control stimulus to contrast subject matter-dependent stimulus impact on HRV and further validate if visual stimulus benefits HRV values regardless of subject matter or personal connection. In this exhibition, nonobjective work was limited to textile quilts focusing on blocks of color and simple shapes. Objective artwork, focused on portraits, landscapes, or still-life compositions, offers viewers a clear and direct connection to the visual immigrant subject matter. Both forms of artistic expression for this research were developed with collected experiences and themes from local undocumented communities in the Salt Lake Valley.

ER encompasses many aspects understood within an individual’s well-being. The psychosocial aspects of belonging encompass the complex interplay between an individual’s ER and their experiences within a social and cultural context. Belongingness is a fundamental human need, and it plays a pivotal role in shaping one’s mental health and overall life satisfaction [3, 7, 12, 18]. Socially, ER affects an individual’s interactions and relationships with others. It can influence social behaviors, including cooperation, empathy, and prosocial actions, as individuals strive to maintain their sense of connection within a group. Additionally, a person’s ability to cope with stressors can dictate self-efficacy and ability to reach out for help [15, 20]. A healthy sense of belonging can contribute to the development of social norms and values within a community [15]. Psychosocial aspects of belonging delve into questions of inclusion, acceptance, and connectedness within various social groups, including family, community, and larger societal contexts [20]. Understanding these psychosocial dynamics is vital for addressing mental health disparities, promoting social cohesion, and fostering a sense of belonging that contributes positively to UI community health.

Methods

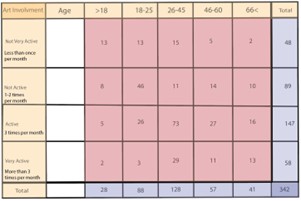

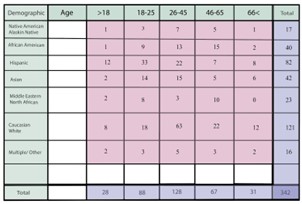

This IRB-approved project aims to gather 300 participating individuals and was able to sample a participating cohort of 342 individuals for an overall powered study. Some of the defining criteria for individuals to participate were age, sex, ethnicity, and health. Individuals with heart conditions or complications were excluded from participating in this research as their HRV results would create outlier data samples. Ultimately, we collected from the surrounding Salt Lake Valley community, immigrant empowerment-focused organizations, and the University of Utah student bodies. The Salt Lake City Arts Council’s Finch Lane Gallery generously provided the space and partial funding for this project. Data collection was collected during regular gallery hours, from August 18th to September 22nd.

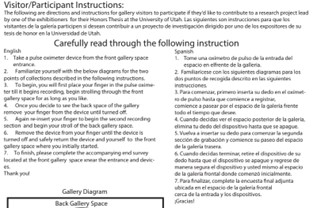

Participants engaged in a structured experience debriefed comprehensively and provided informed consent before the commencement of data collection. To reduce sequential bias we utilized a random number generator (restricted to 1 or 2 on a TI 84 graphing calculator) to assign participants to either the front or backspace first. Participants first experienced the front or backspace, which was dictated by a random number generator (restricted to 1 or 2 on a TI 84 graphing calculator). The gallery layout, participant walking path, and covered entranceways are detailed in Figure 3. Curtains were utilized for entranceways to ensure minimal visual stimulus contamination.

All instructions, surveys, and exhibition writings were presented in both English and Spanish. At the start of their gallery experience, participants were told to choose from three labeled iHealth Air Pulse Oximeters 2023. Participants were instructed to write their device identifier on the back of their end survey, along with starting and ending times, this would be used for data pairing. A two-tailed t-test (P<0.05) was used to determine the statistical difference between different stimuli and the control. Stratification by age was a key analytical approach, recognizing that HRV ranges exhibit variations and narrowing across age groups, as depicted in the decreasing sloped range illustrated in research reference 24.

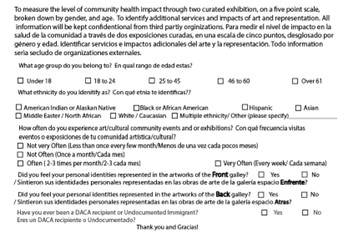

To investigate potential biases regarding specific subject matter related to Latin American identities, we stratified participants by self-identified immigrant status. This stratification aimed to mitigate confounding variables and isolate the true impact of art stimulus exposure on HRV changes by identity. Moreover, we stratified participants by their feelings of representation and connection through a binary option of yes or no to identify with a certain stimulus artwork as seen in Figure 2. This allowed us to analyze trends among individuals who identified or did not identify with the objective vs non-objective artwork, particularly focusing on any significant changes or improvements in their HRV scores.

To ensure clarity in data segmentation, this project incorporated two distinct points of device interaction for participants, demarcating the time range of each data collection period. The first data collection period initiated as participants entered their first designated gallery space, while the second period commenced during the transition to the second gallery space, whether front or back, based on their original designation. Participants concluded their gallery experience by returning the pulse oximeter devices and completing the corresponding end survey.

Given this research sample population surpasses 30 and exhibits general normalcy trends when plotted on a scatter plot, a two-tail T-test is deemed appropriate. Assuming that the true population means remain similar to previous research findings from reference 24, this analysis centers on testing the null hypothesis that there is no discernible difference between the HRV means of individuals experiencing the front versus back gallery space and from the control mean of no stimuli. To validate results for both responses, samples representing individuals who visited the backspace first versus the front space first were confirmed to originate from the same sample population mean and do not impart a corollary impact on HRV via similar T-testing. Further analyses explored potential variations in HRV based on participants’ identification with either gallery exhibition and investigated the statistical significance of HRV results among those who identified as undocumented or DACA recipients compared to the rest of the sampled population.

The curation of artworks, spanning both nonobjective and immigrant-focused themes, was informed by focus groups involving undocumented immigrants, immigrant support organizations, and firsthand experiences. This studies primary investigator painted 15 of the total immigrant-focused artworks. This collaborative approach ensured the construction of a diverse collection of 30 artworks, aligning with the authentic narratives and perspectives of the immigrant community.

Figure 1: English Gallery diagram of front and back space with points of collection highlighted and routes for visitors.

Figure 2: End Survey questions

Figure 3: Finch Lane promotional material for the exhibition.

Figure 4: Briefing and instructional pamphlet included at the front of the gallery space.

Results

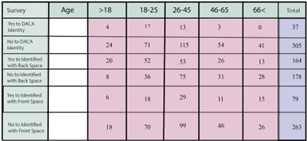

Table 1: Frequency of community arts participation by age and total sample size.

Table 1: Frequency of community arts participation by age and total sample size.

Table 2: Self-identified ethnicities by age range and sample size.

Table 3: Bullion survey question responses against age range and sample size.

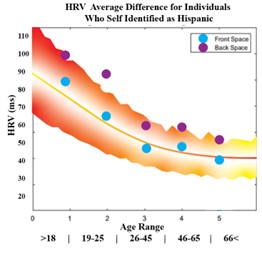

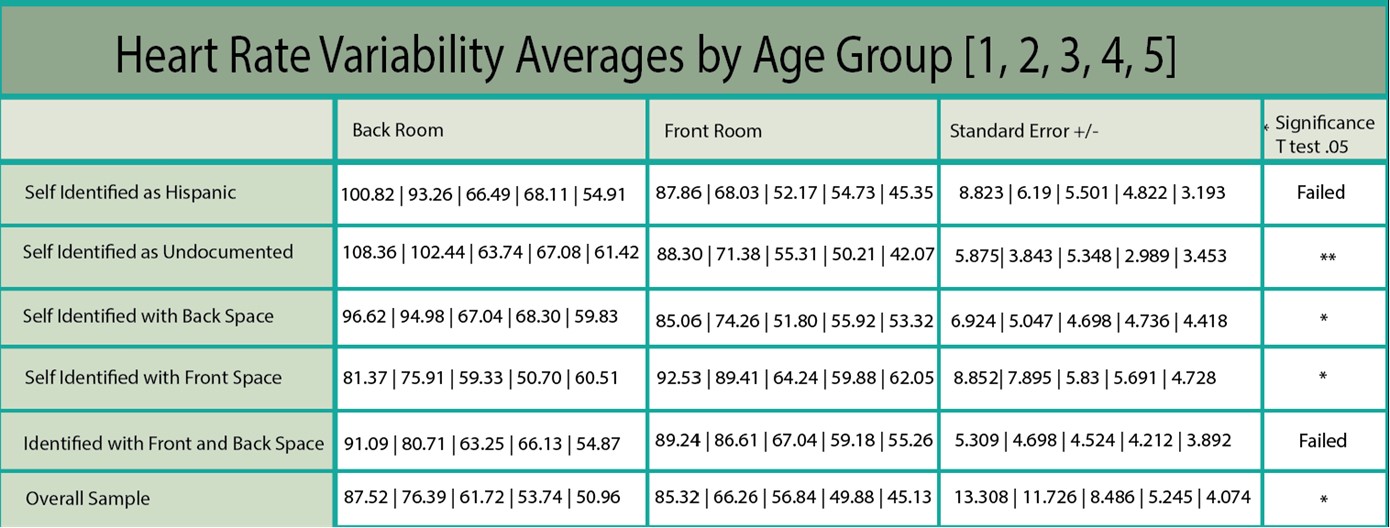

Figure 5: HRV averages by age range for individuals who identified as Hispanic. Individuals regardless of identifying with or not with certain artwork stimuli, were included.

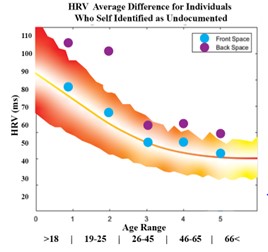

Figure 6: HRV averages by age range for individuals who identified as or have been undocumented immigrants. Data is for all UI individuals who identified with the objective immigrant artwork and then did not identify with the nonobjective abstract artwork.

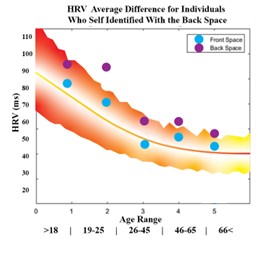

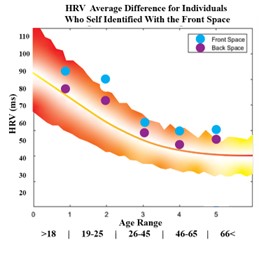

Figure 7: HRV averages by age range for individuals who identified with the backspace exhibition. Data is from any individual who said yes to identifying with the back space’s immigrant-focused artwork and no to identifying with the front space’s abstract non-objective artwork.

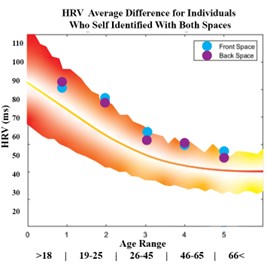

Figure 8: HRV averages by age range for individuals who identified with the front space exhibition. Data for all participants who responded yes to identifying with the abstract nonobjective artwork and no to identifying with the immigrant-focused artwork.

Figure 9: HRV averages for participants who identified with both spaces across age ranges. All individuals who said yes to identifying with the nonobjective abstract artwork and the immigrant- focused artwork.

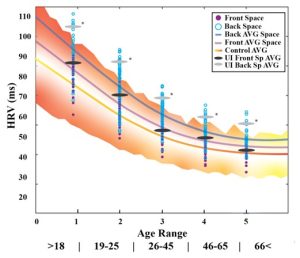

Figure 10: Lines of best fit for whole sample HRV responses to front space stimulus (purple) and backspace stimulus (blue). Averages by age for individuals who identified as undocumented are provided as black (front) and grey (back) ovals regardless of identifying with a specific stimulus.

Table 4: We find no statistically significant difference in HRV between participants who experienced the front space first and the backspace second, and those who experienced the back space first and the front space second. Additionally, we reject the null hypothesis that there is no change in heart rate for participants experiencing the front or back gallery space artworks for the overall sample and UI- identifying participants. Similarly, we reject the null hypothesis that there is no statistical difference in HRV between participants who identified with the backspace artwork and those who did not. However, we fail to reject the null hypothesis regarding participants’ identification with the front space and backspace artwork. Furthermore, the sample means for the front stimulus are statistically different from the overall mean for the back-room stimulus, particularly among participants identifying as undocumented immigrants. Nonetheless, we find no significant difference in heart rate between undocumented immigrant participants and the overall sample mean for both front and back-room stimuli at the .05 significance level, but at a lower tolerance of .1 significance.

Discussion

The UI population in the United States faces numerous challenges, including socioeconomic adversity, social stigmatization, and limited access to essential services, all contributing to significant stressors that threaten their mental and physical well-being. With inadequate support systems in place, interventions aimed at positively impacting the emotional regulation of undocumented immigrants are essential. This study explores the impact of objective and non-objective artwork on heart rate variability (HRV) in this community, hypothesizing that identity-specific artwork can enhance emotional regulation by increasing HRV values after viewing visual stimuli that pertain to their immigrant identities.

Employing a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, we collected HRV samples from undocumented immigrants in a public gallery space. Utilizing pulse oximetry wearable finger devices for HRV analysis, participants were exposed to both objective and non-objective artwork, informed by focus groups of undocumented immigrants. The data, collected from a diverse cohort, involved randomizing participants to experience either immigrant subject matter-based or non-objective artwork first.

These findings indicate a statistically significant improvement in HRV among participants exposed to immigrant subject matter-based artwork in both population samples (Table 3). Although we did not reject the null hypothesis for a statistical difference in HRV response to back-room stimulus between undocumented immigrants (UI) and the sample mean, we did observe a correlation that warrants further investigation, especially at an alpha level of .1 (Table 3). Moreover, the statistical difference revealed in the two-tailed t-test comparing responses to back and front stimuli encourages a stronger association with improved HRV based on subject matter-dependent artwork (Table 3). The fact that the means of this study’s samples for both stimuli were above the non-stimulus mean validates the use of visual stimulus in impacting an individual’s HRV, supporting this study’s hypothesis and suggesting that visual art-based interventions, particularly those culturally relevant, may significantly enhance emotional well- being within the undocumented immigrant community.

Sample randomization minimized response bias through the order of visual stimulus exposure (Table 3), ensuring that these results avoided bias associated with linked stimulus exposure for future observations. The lack of statistical difference in HRV response to the front stimulus between undocumented immigrants and the overall sample mean suggests that abstract artwork without subject matter can positively impact HRV in a diverse population (Table 3). Furthermore, individuals who identified with either the front or back-space exhibited a statistically significant increase in HRV compared to the control group, indicating a positive effect of artwork identification on HRV (Table 3). The statistically significant difference in HRV response to back and front stimuli (Table 3) and the positive increase in HRV response to abstract artwork compared to the control general population (Table 3) confirm the effectiveness of both stimuli in impacting HRV. Additional data confirms that the HRV responses to back and front stimuli come from comparable population means (Table 3), suggesting a link between personal identity and reflected subject matter concerning HRV responses.

There was a visual positive trend for those who identified as immigrants and identified with the subject matter artworks (Fig 10). It is important to note that of the 37 DACA-identifying individuals, all identified with the backspace stimulus (Table 2). All individuals who identified with the front space and backspace showed elevated levels of HRV values (Fig 8,9). HRV values for UI individuals followed the natural trend expected with age (Fig 7). Stratifying HRV values for Hispanic-identifying individuals showed an increase in subjects’ specific responses over abstract works (Fig 6). An aspect that could be further researched is the stratification and focus of the impact of ethnicity on HRV to visual stimulus and subject matter. Along with other metrics within the initial survey, some questions have yet to be analyzed on their impact or relationships with the collected HRV data. Including ethnicity, frequency of art interaction, or primary language spoken that could impact the response of an individual’s HRV.

This study contributes to the existing literature on art therapy, specifically in the context of emotion regulation and HRV applications. Drawing from the foundations laid by previous research [8, 26], extending beyond assessing emotions to explore the implications of emotion regulation assessment in public spaces and among undocumented populations. The growing applications of HRV, traditionally employed in brain imaging, facial recognition, and stress regulation, open new avenues for understanding emotional regulation [25]. This aligns with the evolving landscape of health and community interventions [9, 10, 33], particularly relevant as aging populations and undocumented immigrant communities face increasing stressors [6, 7, 8, 2, 3].

In contrast to the current focus on individual emotion assessment development, this research delves into the practical applications of emotion regulation assessment in real-world settings, shedding light on the potential role of art modalities in enhancing mental well-being on a community scale. This exploration of emotional pathways through HRV, coupled with the consideration of parasympathetic pathways, contributes to modeling community interactions and support systems [9, 10, 33]. This aligns with the broader movement towards integrated health, community, and arts programming, emphasizing the need for innovative praxis [10, 15]. This study extends the understanding of emotional regulation by identifying gaps in existing research, specifically in identity interactions and immigrants’ emotional regulation abilities. While past research has provided insights into the metrics of cardiac chronotropy about emotional regulation and psychological improvement [27], this work highlights the need for identity-specific investigations and a more nuanced examination of vulnerable populations, mirroring efforts in therapeutics for children [17].

However, it’s essential to acknowledge the limitations of this study compared to the broader literature. The relatively smaller and potentially skewed sample size, along with limitations in ethnic diversity, emphasizes the necessity for future research to address these gaps and refine the comprehension of the intricate relationship between emotion regulation and physiological metrics. In summary, this study aligns with key areas in emotion measurement, HRV applications, and their unique intersection in the realm of quantitative physiology-based assessments, offering valuable contributions to the evolving landscape of mental health and community research.

The practical implications of these findings are significant, demonstrating how art-based interventions can be applied in public spaces to support the emotional well-being of marginalized communities. But are limited by the span and availability in which members of the community could interact with the study. Some individuals in the community may not have been able to make the gallery hours due to work or the cost of travel. Other individuals might have been out of town for the two months the exhibition was open so possibly increasing that period would also be beneficial in the future. This study site was public transportation accessible and near a university campus but had limited parking space and was only open from 8 am to 5 pm from Monday to Friday. Additionally, most participants were collected by voluntary choice which could have left the data set devoid of certain individuals who are still important to the overall research aim. In future iterations, a larger space and more accessible location within a population would be ideal to gather as many participants of the community as possible.

Additionally, the consideration of inviting specific groups and project-provided transportation or additional open hours would increase the accessibility of participation. This research took approximately 2 years from conception to execution of the exhibition, with the understanding that some art programs take decades to execute projects this was a quick turnaround that could have benefited from more time and collaboration within that more traditional timeline. The incorporation of a visual video that demonstrated the key instructions for participants could have also increased the accessibility for individuals who found it challenging to navigate the space possibly causing disruptions in their original pulse oximeter data and subsequent HRV results evident in some data outliers.

Looking beyond visual stimuli, the future holds the potential for expanding accessible art therapy research to incorporate a broader spectrum of sensory experiences. Integrating sound environments, and interactive artworks, and tailoring interventions to subject-specific demographics could offer a more personalized and holistic approach. Future research directions may involve expanding sample sizes, exploring additional demographic factors, and refining interventions. Collaboration with health institutions, community centers, and arts programs is crucial for the continued success of this research, aiming to establish permanent installations and spaces tailored to specific communities. Expanding research to incorporate a broader spectrum of sensory experiences, beyond visual stimuli, aligns with the dynamic nature of art therapy and offers innovative applications of HRV. This evolution aligns with the dynamic nature of art therapy, paving the way for innovative applications of HRV in diverse environments under varying stimuli.

References

[1] Garcini L.M. 2018. “Kicks Hurt Less; Discrimination Predicts Distress Beyond Trauma among Undocumented Mexican Immigrants”, Psychology of Violence. Vol 8(6)

[2] K. Hacker, M. Anies, BL. Folb, L. Zallman, 2015, October 30, “Barriers to health care for undocumented immigrants: a literature review”, Risk Manag Healthc Policy, 8:175-83

[3] Garcini L.M. Mental disorders among undocumented Mexican immigrants in high-risk neighborhoods: Prevalence, comorbidity, and vulnerabilities. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017;85(10):927–936. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000237.

[4] S. Haiblum, J. Czamanski, and G. Galili, (2018), “Emotional Response and Changes in Heart Rate Variability Following Art Making With Three Different Art Materials”, Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 9.

[5] M. Mather, J. Thayer, “How heart rate variability affects emotion regulation brain networks” Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2018 Feb;19:98-104.

[6] B. Groot, L. de Kock, Y. Liu, C. Dedding, J. Schrijver, T. Teunissen, M. van Hartingsveldt, J. Menderink, Y. Lengams, J. Lindenberg, and T. Abma, 2021, “The value of active arts engagement on health and well‐being of older adults: A nation‐wide participatory study” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15).

[7] G. E. C. Thomas, S. J. Crutch, and P. M. Camic, 2018, “Measuring physiological responses to the arts in people with dementia”, International Journal of Psychophysiology, (Vol. 123).

[8] M. Pelowski, P.S Markey, J.O Lauring, and H. Leder, 2016, “Visualizing the impact of art: An update and comparison of current psychological models of art experience”, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10.

[9] C. R. Davies, M. Rosenberg, M. Knuiman, R. Ferguson, T. Pikora, and N. Slatter, 2012, “Defining arts engagement for population-based health research: Art forms, activities and level of engagement”, Arts and Health, 4(3)

[10] H. L. Stuckey, and J. Nobel, 2010,”The Connection Between Art, Healing, and Public Health: A Review of Current Literature” American Journal of Public Health, 100(2)

[11] S. Galea, 2021, “The Arts and Public Health: Changing the Conversation on Health”, Health Promotion Practice, (Vol. 22, Issue 1_suppl)

[12] C. Parkinson, and M. White, 2013, “Inequalities, the arts and public health: Towards an international conversation”, Arts and Health, 5(3)

[13] K. Li, & S. Warren, 2012, “A wireless reflectance pulse oximeter with digital baseline control for unfiltered photoplethysmograms”, IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems, 6(3).

[14] R. Yousefi, M. Nourani, S. Ostadabbas, and I. Panahi, 2014, “A motion-tolerant adaptive algorithm for wearable photoplethysmographic biosensors”, IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 18(2).

[15] C.L. Ford, and C.O. Airhihenbuwa, 2010, “Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: Toward antiracism praxis”, American Journal of Public Health, (Vol. 100, Issue SUPPL. 1),

[16] I. R Fatikhov, A. H, Sharafetdinov, T. P, Vasilyeva, A. M, Magomedova, A. H, Fayzullaev, T. V, Tazina, . 2023, “Issues of Treatment and Prevention of Occupational Diseases of Workers in Various Fields of Activity by Art Therapy”, Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results, 14(2), 2306–2308.

[17] L. Steinhardt, 1993. “Children in art therapy as abstract expressionist painters”. American Journal of Art Therapy, 31(4), 113.

[18] E. Ghasemi, R. Majdzadeh, F. Rajabi, A. Vedadhir, R. Negarandeh, E. Jamshidi, A. Takian, & Z. Faraji. 2021, “Applying Intersectionality in designing and implementing health interventions: a scoping review.” BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–13

[19] C.B. Robey, W.R. McCullough, and D.K. El Reda. 2022. “Critical Race Theory for Public Health Students to Recognize and Eliminate Structural Racism.” American Journal of Public Health 112 (6): 850–52

[20] H. Gentile, and S. Salerno. 2019. “Communicating Intersectionality through Creative Claims Making: The Queer Undocumented Immigrant Project.” Social Identities 25 (2): 207–23

[21] R.L. Deitz, L.H. Hellerstein, S.M. St. George, D. Palazuelos, and T.E. Schimek. 2020. “A Qualitative Study of Social Connectedness and Its Relationship to Community Health Programs in Rural Chiapas, Mexico.” BMC Public Health 20 (1): 1–10

[22] R. Perkins, A. Mason-Bertrand, U. Tymoszuk, N. Spiro, K. Gee, A. Williamon, 2021, “Arts engagement supports social connectedness in adulthood: findings from the HEartS Survey”. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–15

[23] J. L. Ohayon, S. Rasanayagam, R. A. Rudel, S. Patton, H. Buren, T. Stefani, J. Trowbridge, C.Clarity, J. G. Brody, & R. Morello-Frosch, 2023, “Translating community-based participatory research into broadscale sociopolitical change: insights from a coalition of women firefighters, scientists, and environmental health advocates”, Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 22(1), 1–14.

[(24)] L Garavaglia, D. Gulich, M. Defeo, M. Thomas, I. M Irurzun, 2021, “The effect of age on the heart rate variability of healthy subjects”. PloS one, 16(10)

[25] J. Czamanski-Cohen, K. L Weihs. 2016, “The Bodymind Model: A platform for studying the mechanisms of change induced by art therapy”, The Arts in psychotherapy, 51, 63–71.

[26] M. Bradley, P. Lang. (1994) “Measuring emotion: the Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential.” J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. Mar;25(1):49-59. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9. PMID: 7962581.

[27] J. Allen, A. Chambers, D. Towers. (2007) “The many metrics of cardiac chronotropy: a pragmatic primer and a brief comparison of metrics.” Biol Psychol. Feb;74(2):243-62. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.08.005. Epub 2006 Oct 27. PMID: 17070982.

[28] M. Adrian, J. Zeman, G. Veits. (2011) “Methodological implications of the affect revolution: A 35- year review of emotion regulation assessment in children.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, Volume 110, Issue 2, Pages 171-197.

[29] Adrian M, Zeman J, Veits G. (2011) “Methodological implications of the affect revolution: a 35- year review of emotion regulation assessment in children.” J Exp Child Psychol. Oct;110(2):171-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.03.009. Epub 2011 Apr 22. PMID: 21514596.

[30] Abbing A, de Sonneville L, Baars E, Bourne D, Swaab H. (2019) “Anxiety reduction through art therapy in women. Exploring stress regulation and executive functioning as underlying neurocognitive mechanisms.” PloS one, 14(12), e0225200.

[31] King JL, Parada FJ. (2021) “Using mobile brain/body imaging to advance research in arts, health, and related therapeutics.” The European journal of neuroscience, 54(12), 8364–8380.

[32] Pham T, Lau ZJ, Chen SH, Makowski D. (2021) “Heart Rate Variability in Psychology: A Review of HRV Indices and an Analysis Tutorial.” Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 21(12), 3998.

[33] Gitler A, Vanacker L, De Couck M, De Leeuw I, Gidron Y. (2022) “Neuromodulation Applied to Diseases: The Case of HRV Biofeedback.” Journal of clinical medicine, 11(19), 5927

[34] Castaldo R, Montesinos L, Melillo P, James C, Pecchia L. (2019) “Ultra-short term HRV features as surrogates of short term HRV: a case study on mental stress detection in real life.” BMC medical informatics and decision making, 19(1), 12

[35] Steffen PR, Bartlett D, Channell RM, Jackman K, Cressman M, Bills J, Pescatello M. (2021) “Integrating Breathing Techniques Into Psychotherapy to Improve HRV: Which Approach Is Best?.” Frontiers in psychology, 12, 624254.

[36] Ratajczak E, Hajnowski M, Stawicki M, Duch W. (2021) “Novel Methodological Tools for Behavioral Interventions: The Case of HRV-Biofeedback. Sham Control and Quantitative Physiology- Based Assessment of Training Quality and Fidelity.” Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 21(11), 3670.