College of Humanities

39 Case Study of Vowel Development in a Bilingual Hard of Hearing Child

Addison Bethards and Tanya Flores

Faculty Mentor: Tanya Flores (World Languages & Cultures, University of Utah)

Abstract

Due to impeded speech perception in hard of hearing children (Bruggeman et al. 2021), their acquisition of vowel sounds may be distorted, which could cause them to produce vowels differently from fully hearing children. Bilingual children follow different paths of speech acquisition, perhaps merging their two vowel systems (Hambly et. al 2012). This case study focuses on the development and production of vowel sounds in a HHH (Hispanic Hard of Hearing) child from a Spanish-English bilingual home. The goal was to track early vowel development and compare the vowel productions of this child in both English and Spanish. This time period corresponded to the first two years of the child wearing hearing assistive devices, thus receiving oral language input for the first time. Through data acquisition and acoustic analysis, we investigated how this child differentiated and/or merged Spanish and English equivalent vowel sounds. Using data gathered for a larger study over a time period of four academic semesters (Flores 2017-2019), we analyzed vowel productions from one male HHH preschool-aged child. The data consisted of storytelling and lexical identification tasks in both English and Spanish at each data collection point. Results of the acoustic analysis showed evidence of emerging bilingualism with differentiation between Spanish and English vowels, as well as the centralization of English sounds. This data demonstrates a unique path of vowel development during early stages of language acquisition for one HHH bilingual child.

Introduction

Linguistically developing children, ages 3 to 8, can encounter multiple factors that may affect or even delay phonetic acquisition. Hard of hearing children tend to have a more delayed speech sound production and perception compared to normal hearing children (Bruggeman et. al 2021). As speech perception can be easily impeded in hard of hearing children, their acquisition of vowel sounds may be distorted, which could cause them to produce vowels differently from fully hearing children. It is not unusual that deaf and hard of hearing children can learn two languages at a time (Bennet 1988; Cohen et al. 1990; Cummins 1992, García-Vázquez et al. 1997; Collier & Thomas 2004; Genesee 2007; Ertmer et al. 2012; Flores 2020). Children who are exposed to two or more languages at a young age can experience crossover between the languages (Hambly et. al 2012). It may be possible that children who are developing phonologically in two languages create their own sound inventory that combines the phonetic and phonological rules/patterns of both languages and their sounds. This case study focuses on the development and production of vowel sounds in a Hispanic hard of hearing child from a Spanish-English home. The goal was to track early vowel development and compare the vowel productions of this child in both English and Spanish over a two-year period. Through data acquisition and acoustic analysis, this research aims to investigate how this child differentiated and/or merged Spanish and English equivalent vowel sounds.

Literature Review

“Bennet (1988) indicates that children of minority groups tend to face more difficulty in school compared to their non-minority peers. Research among deaf and hard of hearing students within a minority group is necessary in order to provide the bilingual language support that is lacking (Guardino & Cannon 2016) due to the many barriers that this community faces. The Utah School for the Deaf and Blind (USDB) served 936 students in the 2015-2016 school year, of which at least 530 were children. In the past few years, about 30% of these children served came from Spanish-speaking homes (Salazar 2016). Children of the HHH community face delayed medical intervention–while the majority of hard of hearing children receive a hearing aid by age one, most of the Latino children don’t receive a hearing aid until after the age of two. Due to this delay, their bilingual development (in both English and Spanish) is impeded, which causes these Hispanic students to stay in the LSL program longer (about 2-4 years) than their non-Hispanic peers.”

This impeded bilingual development was mostly due to a general lack of information and limited access to materials in both Spanish and English (Flores 2020).

Addressing language acquisition where two languages are present in the child’s life is necessary because subtractive second language learning (eventual loss of first language) can have negative cognitive effects. Research has shown that students who enroll in intervention earlier tend to have a greater academic success rate (Bennet 1988; Cohen et al. 1990; Cummins 1992, García-Vázquez et al. 1997; Collier & Thomas 2004; Genesee 2007; Ertmer et al. 2012). Speech production accuracy is also correlated to the amount of time the child can access audio signals with a hearing device. Additive bilingualism (in which both languages develop simultaneously) has positive cognitive effects on language development. Thus, for HHH children who are learning two languages, research in bilingual language acquisition (in this case, vowel sound acquisition and development) is necessary to address and better understand their language development.

The current study involves creation and analysis of vowel spaces of a bilingual hard of hearing child. Vowel spaces (Figure 1 data) indicate tongue placement within the mouth when producing the sounds (Hualde & Colina 2014). The vertical plane (F1) indicates height of the tongue; a higher F1 value is lower in the mouth and lower F1 value is higher tongue placement. The horizontal plane (F2) indicates tongue position in the mouth. Lower F2 indicates posterior tongue position; middle F2 is a central position and higher F2 is an anterior position. A typical target Spanish vowel space consists of five vowels arranged in a triangle (Hualde & Colina 2014): two high vowels /u o/, two middle /e o/ and one low /a/. In the horizontal dimension, there are two anterior /i e/, one central /a/ and two posterior /u o/. A typical target English vowel space consists of multiple vowels in a quadrilateral-like shape (Disner & Ladefoged 2012). Some of these vowels include high anterior /i/, middle anterior /ɛ/, low anterior /æ/, central /ə/, low back /a/, and high back /u/.

Methods

The subject of the case study was one of the participants in Flores’ (2020) study. This hard of hearing child was male and 7 years old (at the time of the study), from a family with at least one parent who is a native Spanish speaker. Over a time period of four semesters (two years’ worth of data that were analyzed from Flores’ project beginning in 2018), we analyzed speech production through recorded storytelling samples of the child in English and Spanish. Where target vowel sounds were lacking in the storytelling samples, we extracted word samples from recorded phonetic tasks (the child stating the corresponding word when presented with a flash card). We created word lists (clearly produced words) from the recordings from every semester in Spanish and English. Target vowel sounds were identified from these lists. We analyzed these vowel sounds using Praat software to measure the vowel properties, finding F1 and F2. These measurements were taken for all target vowel sounds. Average F1 and F2 were calculated for each vowel sound to create corresponding vowel spaces for English and Spanish for every semester. This was followed by comparison and analysis of vowel spaces across the four-semester period.

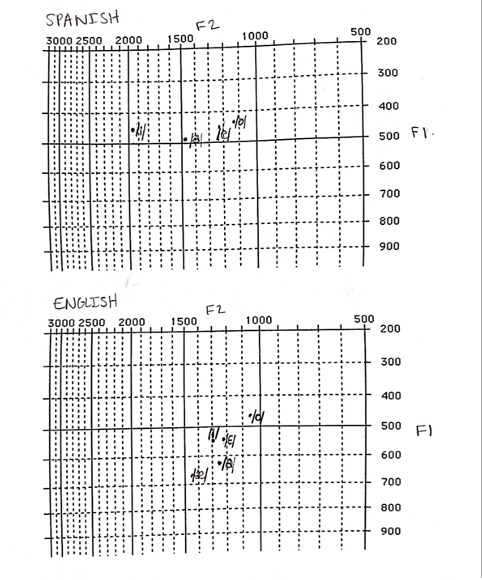

Figure 1: Fall 2017 Vowel Spaces

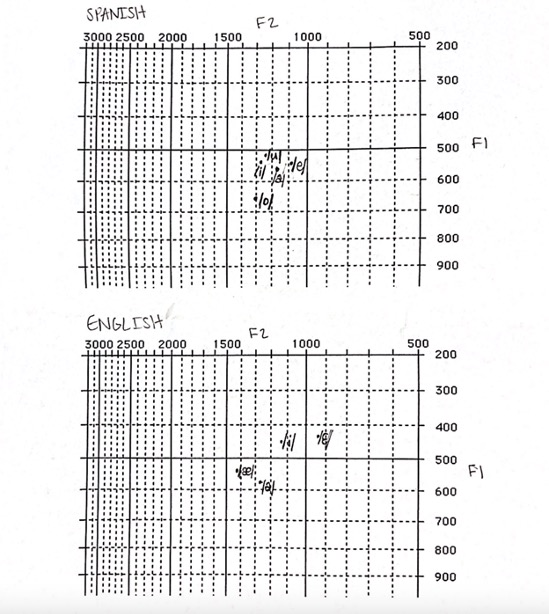

Figure 2: Spring 2018 Vowel Spaces

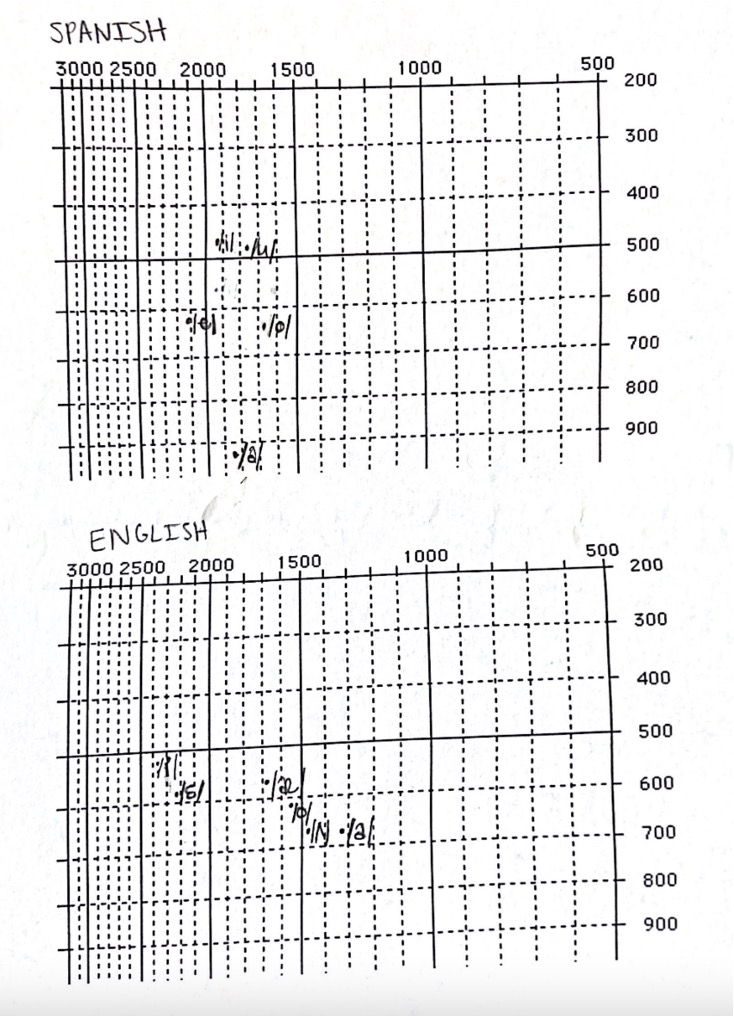

Figure 3: Fall 2018 Vowel Spaces

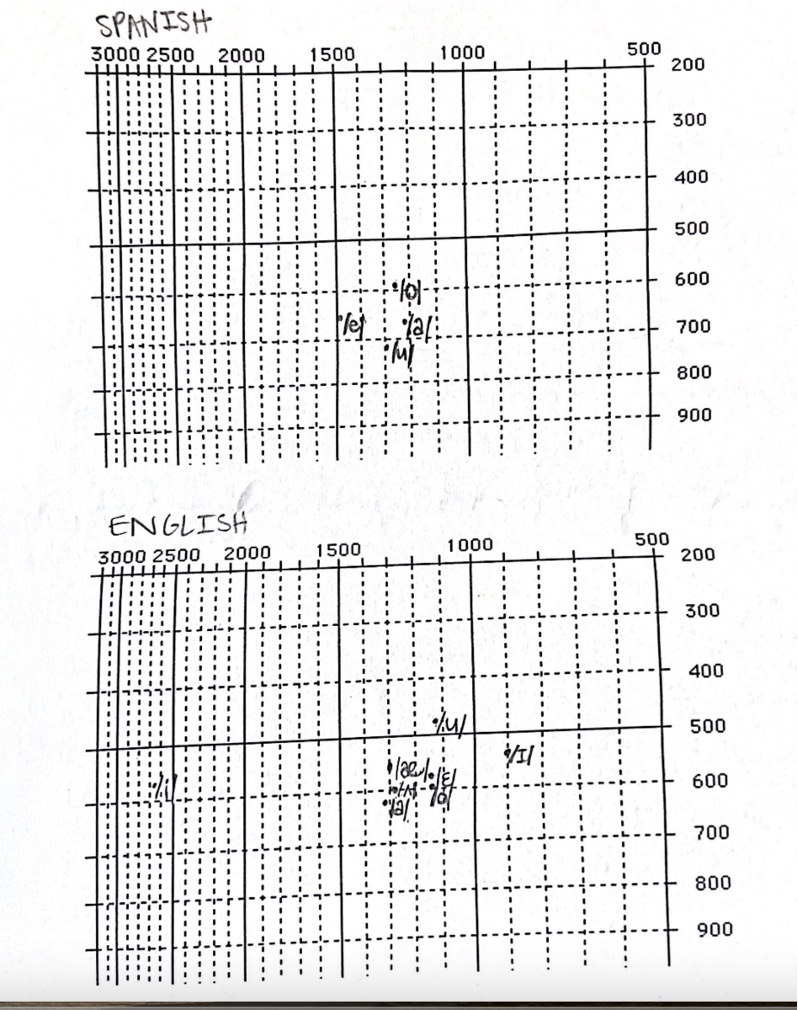

Figure 4: Spring 2019 Vowel Spaces

Results

Results of the acoustic analysis (formant measurements calculated by Praat and plotted vowel spaces based on average F1 and F2 measurements) showed evidence of emerging bilingualism with differentiation between Spanish and English vowels, as well as the centralization of English sounds. The following data (as obtained from Spanish and English vowel spaces) demonstrates a unique path of vowel development during early stages of language acquisition for one HHH bilingual child.

First semester data (Fall 2017) show relative target-like Spanish vowel distinctions (lower /a/, higher /o/, and higher /i/). The /e/ vowel appears further back than a target-like position. English vowel space shape does not follow the typical quadrilateral shape. The vowel space is not target-like; /æ/ is lower than /a/.

As shown in the vowel spaces for Spring 2018, the entire Spanish vowel space moves further downward, both F1 and F2 lowering. Additionally, /e/ has moved back and appears to be at a more central position. The English vowel space spreads further apart. English /a/ has dropped lower in F1.

In the following semester (Fall 2018), the Spanish vowel space has moved forward, all vowels showing higher F2s. The differentiation between Spanish vowels in relation to each other in the vowel space is target-like. The English vowel space has moved forward as well, showing higher F2s. There appears to be more trouble with vowel differentiation between sounds /o/, /a/, and /ʌ/.

In the final semester, Spring 2019, the Spanish vowel space drops lower and further back than its position in Fall 2018, with evidence of some vowel centralization. Differentiation is clear but /u/ is still lower than a target-like position. The English vowel space has moved back; however, the /i/ sound remains forward, with a higher F2 in relation to all other vowels. Evidence of vowel centralization is present. There appears to be trouble with placement of high sounds /u/ and /i/.

Discussion

Differences between Fall 2017 and Spring 2018 vowel spaces indicate /e/ movement forward. During this period, the child’s hearing has improved due to implementation and wearing of hearing aids. As /e/ is more central; bilingualism seems to be emerging. Correction of /a/ as it drops further in Spring 2018 is apparent. Differences between languages show processes of both differentiating and merging of vowels. In Fall 2018 we see some accomplishments on differentiation between English and Spanish but a target-like vowel space for English is still emerging. More English centralization is present in Spring 2019; the child may recognize it is more acceptable in English to use similar sounds (approximating an /ə/ sound) using little differentiation. Spanish vowels have vowel placements similar to English but with less centralization, thus bilingualism is emerging.

Overall data from acoustic analysis indicates that in early vowel development of this bilingual hard of hearing child, there is emerging bilingualism with differentiation between Spanish and English vowels, as well as the centralization of English sounds. This case study uses both phonetic tasks and storytelling samples. Further research can be done to represent vowel development more accurately in running speech, using only storytelling samples. As it is a case study, expanding research to a greater population of bilingual hard of hearing children could support this project with more examples and information on vowel development.

The purpose of this study was to find out if a bilingual hard of hearing child differentiated or merged Spanish and English vowel sounds across a time period of four semesters. In early stages, vowel placements appear to merge, and later sessions indicate developed vowel differentiation. The child has distinguished between Spanish vowel sounds and English vowel sounds at the end of these semesters. These findings may provide insight on bilingual speech sound acquisition among hard of hearing children and can contribute to providing information and helpful resources for those who come from Spanish-speaking homes.

References

Bennett, A. T. (1988). Gateways to powerlessness: Incorporating Hispanic deaf children and families into formal schooling. Disability, Handicap & Society, 3(2), 119–151.

Bruggeman, L., Millasseau, J., Yuen, I., & Demuth, K. (2021). The acquisition of acoustic cues to onset and coda voicing contrasts by preschoolers with hearing loss. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(12), 4631–4648. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_jslhr-20-00311

Cohen, O. P., Fischgrund, J. E., & Redding, R. (1990). Deaf children from ethnic, linguistic and racial minority backgrounds: An overview. American Annals of the Deaf, 135(2), 67–73.

Collier, V. P., & Thomas, W. P. (2004). The astounding effectiveness of dual language education for all. NABE Journal of Research and Practice, 2(1), 1–20.

Cummins, J. (1992). Bilingual education and English immersion: The ramírez report in theoretical perspective. Bilingual Research Journal, 16(1-2), 91–104.

Disner, S.F., & Ladefoged, P. (2012). Making English Vowels. In Vowels and consonants. essay, Wiley-Blackwell.

Ertmer, D. J., Kloiber, D. T., Jung, J., Kirleis, K. C., & Bradford, D. (2012). Consonant production accuracy in young cochlear implant recipients: Developmental sound classes and word position effects. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(4), 342–353.

Flores, T. (2020). A community-based participatory research project involving Latino families of deaf and hard-of-hearing children. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 12(2).

García-Vázquez, E., Vázquez, L. A., López, I. C., & Ward, W. (1997). Language proficiency and academic success: Relationships between proficiency in two Languages and achievement among Mexican American students. Bilingual Research Journal, 21(4), 334–347.

Genesee, F. (2007). French immersion and at-risk students: A review of research evidence. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(5), 654–687.

Guardino, C., & Cannon, J. E. (2016). Deafness and diversity: Reflections and directions.

American Annals of the Deaf, 161(1), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2016.0016 Hambly, H., Wren, Y., McLeod, S., & Roulstone, S. (2012). The influence of bilingualism on

speech production: A systematic review. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48(1), 1–24.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00178.x

Hualde, J. I., & Colina, S. (2014). Vocales. In Los Sonidos del Español. essay, Cambridge University Press.

Salazar, J. (2016-2017). USDB Listening and Spoken Language Director. Personal communication with Dr. Flores.