Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine

61 The Social Determinants of Mental Health Stigma and The Role of Social Influence

Hannah Berrett

Faculty Mentor: Michelle Vo (Psychiatry, University of Utah)

Abstract

Social influence is our response to the social environment, encompassing thoughts, emotions, actions, and our tendency to follow norms, conform, and obey authority. Three types of social influence including normative (i.e., conformity to groups), informational (i.e., seeking advice or information), and authority influence (i.e., obedience to authority figures) were examined in relation to one another and social identity (an individual’s self-concept derived from perceived membership in a relevant social group). Further, social influence and aspects of social identity (age, generation, gender, religion, race/ethnicity, and student/faculty status) were examined in relation with comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceptions of mental health stigma within the community, and help-seeking behavior. The study aimed to (1) explore if specific aspects of social identity and types of social influence were correlated; and (2) identify factors (i.e., type of social influence and social identity) that correlate to perceptions of mental health stigma in the community, comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, and help-seeking behavior. The study recruited 86 University of Utah student and faculty participants ranging from 18-64 years old to participate in a 13-question online survey. Findings confirmed a correlation between comfort discussing mental health with family/friends and perception of stigma within the community, indicating that greater ease in discussing mental health may reduce perceived stigma. However, no correlations were found with help-seeking behavior among aspects of social identity, types of social influence, comfort levels discussing mental health challenges, and perceptions of mental health stigma within the community. Comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends were correlated with gender, with men expressing higher discomfort than women. Christians reported higher levels of authoritative social influence compared to Agnostics, indicating potential differences in obeying authority among religious groups. The study’s findings revealed associations between perceptions of mental health stigma, discomfort discussing mental health issues with family and friends, and social identity factors like gender and religious affiliation. These insights emphasize the need for targeted interventions to foster open dialogue and combat stigma in discussions of mental health, further examine the correlation between authoritative social influence and religion, and additionally explore roles that social influence and social identity generally play in daily decision-making.

Both social influence and social identity play substantial roles in daily decision-making and opinions regarding mental health stigma and help-seeking behavior. Heinzen and Goodfriend (2019) define social influence as the way we react to our social environment, which includes our thoughts, emotions, and actions, as well as our inclination to comply with social norms, conform to others, and obey those in positions of authority. A person’s social identity, an individual’s self-concept derived from perceived membership in a relevant social group, encompasses various aspects such as age, generation, gender, religion, race/ethnicity, and student/faculty status. Exploring the likely correlation between a person’s social identity and social influence could offer insight into how these traits shape an individual’s attitudes, opinions, group conformity, and daily decisions.

Further, by specifically examining the aspects of a person’s social identity and types of social influence, numerous potential attitudes and judgements concerning mental health stigma and help-seeking may arise. Based on our hypotheses, we expect find positive correlations between normative and informational social influence, as well as between these influences and authority influence. We also anticipate that factors like age, gender, and race/ethnicity will be associated with attitudes towards mental health stigma and help-seeking behaviors. Additionally, we predict differences in stigma and help-seeking behaviors between college students and faculty members, as well as across different age groups and racial/ethnic backgrounds.

Social Influence

Deutsch and Gerard (1954) defined normative social influence as when a person follows and joins a group intending to try to fit in with that group. In other words, individuals feel the need to conform their attitudes and opinions to be liked in a group. With this kind of motivation, people join groups for safety, power, desire to form a certain impression, or out of fear or embarrassment (Deutsch & Gerard, 1954). Normative influence, also known as implicit social influence, is the idea of following subtle, unwritten rules that are communicated nonverbally (Heinzein & Goodfriend, 2019). One explanation provides that normative social influence can explain peer group pressure, leading to emotional and attitudinal shifts, resulting in heightened levels of attitude modification (Guimond, 1997).

Informational social influence is when a person conforms to a group to gain knowledge, or because they believe that someone else is right (Deutsch & Gerard, 1954). By extension, informational influence (also known as explicit social influence) often involves doing something due to compliance or obedience (Heinzein & Goodfriend, 2019). These things are done through agreeing to someone’s request or obedience by following an order of an authority figure (Heinzein & Goodfriend, 2019). For example, informational social influence could be seen in a classroom setting where students are discussing a complex topic.

One student, unsure of the correct answer, observes that most of their peers seem to agree on a particular viewpoint. To gain knowledge, the student decides to agree with the group’s opinion, even if it differs from their initial beliefs. It is acknowledged that people who are informationally influenced do not join the group out of necessity, but rather out of choice to try and gain something they think that they lack (Heinzein & Goodfriend, 2019). For example, studies have shown that people’s sensitivity to informational influence, which is driven by a desire for information, is intensified during group discussions (Werner et al., 2008). Additionally, research has revealed that heightened information exchange within these discussions led to a greater likelihood of opinion change and group conformity to a single perspective (Mallinson & Hatemi, 2018; Werner et al., 2008).

Authoritative influence (an extension of informational influence) refers to the influence that individuals with perceived expertise or individuals in a position of power have on the opinions and behaviors of others (Heinzein & Goodfriend, 2019). One study that initially demonstrated this idea was Asch’s 1951 study (Asch, 1951) which demonstrated the power of authoritative influence in an experiment where participants were asked to judge the length of lines. When participants of both studies gave clearly incorrect responses, participants conformed to the group’s opinion, even when it contradicted their own perceptions regarding the length of the line. This effect was particularly strong when the stooges (participants placed to carry out the experimenter’s instructions for the purpose of the research) were perceived as having greater knowledge or expertise than another participant, which Deutsch and Gerard (1954) further identified as participants also experiencing informational influence. These studies highlight the role that both power and authority figures play in shaping the opinions and behaviors of others. Additionally, these studies introduce how individuals perceive social roles, conformity, and obedience.

Since conformity is closely linked to social influence, indicating that people frequently adjust their behavior, beliefs, or opinions to align with perceived correctness. Individuals often seek conformity to adhere to social norms, fulfill a social role, align with a group, or a combination of these factors. Furthermore, obedience aligns closely with conformity, highlighting the direct association between various types of social influence (such as normative, informational, and authoritative social influence) within groups (Heinzein & Goodfriend, 2019). In most situations, the desire to be right and to be liked act together, therefore both normative and informational social influence often coincide. By extension, normative and informational social influence often coincide with the decision of an authority figure, forming their connection to authoritative influence. In other words, an authority figure’s power and status gives them the ability to influence others through both normative and informational social influence. This connection between authority and social influence highlights the importance of considering the role of authority in understanding how people make decisions and behave in social situations.

Building upon the interconnected nature of various forms of social influence, this study hypothesizes that there exists a positive correlation between normative and informational social influence among individuals. Specifically, individuals who conform to social norms out of a desire to be liked (normative influence) are likely to also seek information from others to validate their beliefs or actions (informational influence). Moreover, it is hypothesized that both normative and informational social influence will demonstrate a positive correlation with authoritative social influence, as individuals may be more inclined to conform to social norms or seek information from others when directed by an authority figure. This hypothesis is grounded in the premise that authority figures possess the power and expertise to form others’ opinions, attitudes, and values through normative and informational social influence.

Social Identity

Social identity is generally defined as what makes up a person’s external group identity, including things such as age, generation, gender, religion, race/ethnicity, and student/faculty status as aforementioned (Hogg et al., 2017). Social identity is determined by the attributes shared with other members of a social category (Hogg et al., 2017), while personal identity is determined by terms of personal attributes and relationships (Hogg et al., 2017). Additionally, three forms of self are identified including the individual self, relational self, and collective self. The individual self exemplifies personal traits that differentiate oneself from others, the relational self focuses on one’s qualities derived from personal relationships, and the collective self is an individuals’ aspects based on membership in social groups or categories (Hogg et al., 2017). Each of these forms of self entail social identity and demonstrate how social identity is shaped.

Correspondingly, self-categorization determines how a person chooses to belong to and identify with groups (Mackie et al., 2008). It can also dictate a person’s emotions and their outlooks on certain decisions in group settings. For example, while attending school, a student who identifies themselves as a high- achieving academic may experience positive emotions such as pride and satisfaction while attending school, while a student who categorizes themselves as a struggling learner may experience negative emotions such as frustration and self-doubt. The intergroup emotions theory presents ideas on how people can experience different emotions through self-categorization depending on whether they see themselves as unique individuals or as members of a group (Mackie et al., 2008). Social identity theory suggests that people categorize themselves into various social groups to build their own social identity (Hogg et al., 2017). Similarly, the intergroup emotions theory indicates that when a specific social identity is activated, individuals interpret events based on their impact on the group rather than on a personal level (Mackie et al., 2008). Together, these theories highlight how both social and personal categorizations can influence an individual’s choice to identify with groups or on an individual level. Further, it determines how social identity plays into self-categorization within groups, thus answering the question on how the social identity of an individual can contribute to their decisions where social influence is involved.

Social Identity and Social Influence

The idea of an association between social influence and how individuals form ideas, opinions, and values that motivate their choices in group settings allows for further research. In group settings, it has been determined that someone will conform to the norms and values of the group to be accepted or to not witness disapproval of others (Heinzein & Goodfriend, 2019). These acts of conformity are especially strong when the group represents an important aspect of an individual’s social identity. Since a person’s social identity is derived from their membership in a particular social group or category, we can see the link between social identity and individuals’ decisions, opinions, values, and ideas within groups (Hogg et al., 2017). There is gap in research on if normative, informational, or authoritative social influence are directly tied to specific aspects of social identity such as age, generation, gender, religion, race/ethnicity, and student/faculty status. The social identity of individuals may contribute to their sensitivity to social influence, but to what extent remains unclear.

Grounded in the premise that social identity influences individuals’ sensitivity to social influence within group settings, this study hypothesizes that specific aspects of social identity, including age, generation, gender, race/ethnicity, religion, and student/faculty status, are directly tied to particular types of social influence. It is anticipated that individuals will exhibit higher levels of a certain type of social influence (normative, informational, or authoritative) to group norms and values when those norms align closely with their social identity dimensions. For instance, younger individuals may be more inclined to conform to peers of the same age group to be liked (normative social influence). The study will also examine if participants perceive themselves as sensitive to social influence in general (general social influence) to assess their awareness and responsiveness to external influences on their behaviors and decisions.

Mental Health Stigma and Help-Seeking Behavior

Stigma can be defined as deeply discrediting attribute that lessens a person from a healthy, whole person to a tainted, discounted one (Goffman, 1963). Mental health stigma refers to negative attitudes and perceptions that society holds towards mental illness and those who experience it. Many social psychologists hypothesize social influence is the root cause of stigma (Ahmedani, 2011). Without the social norms put in place by groups, individuals would not feel the influence of their peers, and thus stigma might not be as immense of an issue. Specifically in relation to mental health stigma, people wouldn’t feel judgement, disapproval, or fear in utilizing help-seeking behaviors (Klik et al., 2018).

Help-seeking behavior can be defined as the actions that individuals take to seek support and assistance when they are experiencing mental health issues. An example of help-seeking behavior is when a person who is struggling with a mental health issue seeks professional counseling or therapy to address their concerns. The two concepts of help-seeking behavior and mental health stigma are closely related because mental health stigma can act as a barrier to help- seeking behavior. People may feel ashamed or embarrassed to admit that they are struggling with mental health issues, and they may worry about the negative consequences of seeking help, such as discrimination or social rejection based on their social identity (Hogg et al., 2017).

Multiple research studies have shown correlations between various measures of mental health stigma and help-seeking behavior. For example, it has been found that mental illness stigma impacts help-seeking (Klik et al., 2018) and that stigma is negatively associated with medication use, counseling/therapy visits, and informal support (Gaddis et al., 2018). Another research study found that help-seeking for individuals with mental illness and mental health stigma must be considered with its connection to family and friends’ perceptions of mental health stigma and the perceptions of stigma within their community (Shefer et al., 2012). Similarly, another study found that perceived community attitudes of mental health influence help-seeking intentions (Chen et al., 2016). These studies prove useful because they found correlations with mental health stigma and help-seeking behavior, and further focus on how this correlation could exist because of beliefs held by family, friends, and the community. Our hypotheses regarding mental health stigma in this study include: (1) Perceptions of mental health stigma may be correlated with comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with friends and family; (2) Help-seeking behavior is correlated with perceptions of mental health stigma and comfort level discussing mental health challenges with family and friends.

Social Identity, Mental Health Stigma, and Help-Seeking Behavior

There is research on how aspects of social identity are associated with mental health stigma. Stigma associated with mental illness often leads to negative self-perceptions and a reluctance to seek help (Corrigan et al., 2014; Klik et al., 2018; Vogel, et al., 2007). However, individuals may be more likely to seek help when they identify with social groups that support seeking treatment because of the presence of social influence (Klik et al., 2018). This is seemingly especially the case among those within the same age groups (Knoll et al., 2017). Evidence suggests that in surveys and resurveys of groups of younger and older people over the span of several years, that attitudes of older people typically show less change than do those of younger people (Myers & Twenge, 2022).

Further research on older adults has shown that those between the ages of 55 and 74 generally hold positive attitudes and beliefs about treatment, making such beliefs unlikely to hinder help-seeking behavior (Corey et al., 2008). Other research has found that the ability to resist social conformity pressure is enhanced across the adult life span due to improved emotional regulation with age (Castrellon et al., 2023). However, contradicting research provides the idea that those with self-identified with having a mental illness, specifically faculty at the university level, may prolong stereotypes that mental illnesses are intrinsic weaknesses, and that seeking help is a barrier to academic success (Smith et al., 2022). This specific study by Smith and his colleagues (2022) provides insight for this study’s purposes because of the university population.

Another study by Vogel, Wade, and Hackler (2007) found that college students who perceived greater stigma surrounding mental health issues were less likely to seek help for their own mental health concerns. Similarly, a study by Corrigan, Druss, and Perlick (2014) found that public stigma towards mental illness was associated with lower levels of engagement with mental health services among individuals with serious mental illness. Choudhry and his associates (2016) noted that in college settings, there tends to be a negative perception of mental health and seeking support for it, partly because of the prevailing societal emphasis on physical health over mental well-being in institutional policies and practices. Further, studies have shown that younger college students often experience higher levels of personal stigma toward mental health issues, which is negatively associated with their help-seeking behavior (Eisenberg et al., 2009). This stigma contributes to a tendency to pass judgement on those who have mental health issues or are seeking out mental health resources.

From this, it is hypothesized that college students, regardless of age, will exhibit higher levels of perceptions of mental health stigma within the community compared to faculty members. Additionally, it is hypothesized that students will exhibit higher levels of discomfort discussing mental health challenges with family and friends and lower levels of help-seeking behavior. Conversely, it is hypothesized that faculty members will demonstrate both lower levels of stigma and lower levels help-seeking behavior compared to students. Furthermore, based solely on age as a predictor, this study hypothesizes that there is a significant correlation between age and mental health stigma, as well as age and help-seeking behavior. This study hypothesizes that distinct age groups will exhibit varying attitudes and behaviors towards mental health issues. Further based on previous research indicating age-related differences in attitudes toward mental health (Corey et al., 2008; Knoll et al., 2017; Myers & Twenge, 2022), it is hypothesized that people ages 18-30 are more likely to feel uncomfortable talking about mental health with family and friends. Additionally, they may perceive a higher stigma associated with mental health in their community and are less likely to seek help compared to those ages 31-64.

It is acknowledged that mental health stigma is relevant in other contexts of social identity including gender (Ahmedani, 2011). Research has linked men’s silence regarding mental health stigma to be specifically difficult when discussing it with one’s spouse, other family members, friends, and in the community (Herron et al., 2020). The same research study showed how often men have increased difficulty discussing their mental health with their fathers and other men (Herron et al., 2020). Additionally, Herron and his colleagues (2020) discussed how seeking help for mental health issues may be viewed as a deviation from traditional gender roles that could lead to feelings of shame, isolation, or fear. This is consistent with prior research suggesting that seeking help for mental health issues might be seen as departing from traditional masculinity or gender norms. Such norms, often associated with role-bound activities that emphasize individualism in men, can make them less inclined to discuss their mental health openly with others (Diekman & Early, 2000; Juvrud & Rennels, 2016). From this research, it is hypothesized that gender will exhibit a correlation with comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, with men expressing higher levels of discomfort. It is also anticipated that there will be variations in perceptions of mental health stigma within the community between genders.

Further, it is often indicated that race/ethnicity exhibits correlations with mental health stigma (Ahmedani, 2011). For example, one study found that cultural values related to race/ethnicity are important regarding mental health stigma, specifically in Asian Americans and African Americans (Abdullah & Brown, 2011; Cheng et al., 2018). These studies found that factors such as life experiences, perceptions of dangerousness of mental illness, and historical injustices and mistreatments by the healthcare system significantly impact stigma levels in these communities. Additionally, discussion has often leaned to how ethnic minority people have poorer mental health outcomes compared to White majority populations (Kapadia, 2023). However, other research has discussed that there were no correlations between mental health stigma, help-seeking behavior, and racial/ethnic minority status (Tran, 2021). For this study, it is hypothesized that there will be differences across racial/ethnic groups in comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, differences in perceptions of mental health stigma within the community, and help-seeking behavior for mental health issues. Specifically, it is expected that individuals from different racial or ethnic backgrounds will exhibit varying levels of comfort, perceptions of stigma, and engagement in help-seeking behaviors related to mental health issues.

Overview of the Current Research

Understanding how diverse kinds of social influence and social identity play into individuals’ daily decision-making processes within groups is fundamental. This study aims to examine the correlation between factors of social influence and social identity to determine if certain aspects of social identity are more strongly correlated with aspects of social influence.

Understanding these connections could demonstrate the dynamics shaping individual behavior within social contexts, such as mental health stigma and help- seeking behavior. With an increasing prevalence of mental health concerns and the appreciation of stigma as a barrier to help-seeking behaviors, this study further aims to explore if factors of social influence and social identity discourage positive mental health attitudes and help-seeking behavior.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited using University of Utah’s Study Locator Website, in-person contact, written advertising (flyers, website postings), and social media advertising. University-approved flyers were strategically placed across campus, including official University of Utah building bulletin boards and online platforms. Social media and online advertising were exclusively posted on official University of Utah accounts. For this study, two inclusion criteria were used: participants had to be over the age of 18 and participants had to be a student or faculty member at the University of Utah.

Measures and Procedure

After giving informed consent, participants completed the survey titled “Factors of Mental Health and Social Influence”. The survey included 43 questions, but only 13 were used for data analysis in this study. Some quantitative questions used close-ended scales with 5-point Likert-type responses (where 1 is very low and 5 is very high) while others used binary yes and no response options. Correlations were examined to determine if social identity factors including age, generation, gender, religion, race/ethnicity, and student/faculty status were significantly correlated with comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceptions of mental health stigma within the community, and help-seeking behavior based on initial hypotheses. Other hypotheses were tested by examining correlations between aspects of social identity (age, generation, gender, religion, race/ethnicity, student/faculty status) and four types of social influence (normative, informational, authoritative, general). Correlations among the four types of social influence were also examined, along with if these four types of social influence were correlated with comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceptions of mental health stigma within the community, and help-seeking behavior for further study related to our hypotheses. The study was administered online on Qualtrics through personal computers or phones and took approximately 15 minutes to complete. The nature of the survey was entirely anonymous. Due to the anonymity of the survey, participants were not compensated.

All participants (N = 86) initially completed demographic questions, including questions about age, generation, gender, religion, race/ethnicity, and student/faculty status at the University of Utah. The sample size of 86 participants was determined based on respondents who completed at least 90% of the survey. Out of the initial pool of 96 participants, those who met this completion threshold were included in the sample to ensure data quality for analysis. Participants were then prompted to complete further questions on normative social influence, informational social influence, authoritative social influence, general social influence, help-seeking behavior, and mental health stigma that were developed solely for this research.

Social Influence Questions

One question aimed to assess normative social influence based on its definition by asking whether participants had ever felt the need to conform to the behavior or beliefs of a group they belong to, with response options being “yes” or “no”. To assess informational social influence, one question inquired whether participants had ever relied on information or advice from others to make decisions or form their opinions, with response options being “yes” or “no”. To assess authoritative social influence, participants were asked to indicate how important it was for them to respect and obey the instructions of authority figures on a scale of importance from 1 (indicating “very low”) to 5 (indicating “very high”). An additional question was asked regarding social influence in general, which was referred to as general social influence, asking participants to consider their overall sensitivity to social influence on a scale from 1 (indicating “very low”) to 5 (indicating “very high”).

Help-Seeking Behavior & Mental Health Stigma Questions

To assess help-seeking behavior among participants, one question asked if participants had sought professional help or support if they had experienced any mental health challenges or concerns, with response options of “yes” or “no”. Two questions were designed to assess participants’ perceptions of and experiences with mental health stigma. Participants were first asked to rate their comfort level in discussing mental health challenges with family or close friends on a scale from 1 (indicating “very low”) to 5 (indicating “very high”). In their own opinion, participants were asked to assess how stigmatized seeking professional help for mental health issues was in their community, rating it on a scale from 1 (indicating “very low”) to 5 (indicating “very high”).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The study examined five continuous variables: age, comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceived mental health stigma within the community, authoritative social influence, and general social influence. All continuous variables had 86 respondents, except comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends (75 respondents) and perceived mental health stigma within the community (74 respondents). Age ranged from 18 to 64 years old with a median age of 25 (M = 29.63, SD = 11.77).

Comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends yielded a median score of 4 (M = 3.68, SD = 1.34). This median score falls above the midpoint of the scale, indicating that, on average, respondents generally felt somewhat comfortable discussing mental health challenges with their family and friends. Scores for perceived mental health stigma within the community revealed a median score of 3.5, (M = 3.07, SD = 1.24), suggesting that respondents perceived a moderate level of mental health stigma within their community.

Authoritative social influence had a median score of 4 (M = 3.81, SD = 1.13) indicating that respondents exhibited a moderate level of obedience to authority on average. General social influence had a median score of 3 (M = 2.70, SD = 1.11). This mean score is slightly below the midpoint of the scale, suggesting that, on average, respondents perceived a lower level of themselves being sensitive to social influence.

Additionally, demographic variables (along with information about religious affiliation and University of Utah student or faculty status) were analyzed to determine frequencies and percentages for 86 participants (excluding 3 respondents who didn’t identify with provided generational options). In the distribution, 44 (51.2%) individuals identified as women, and 42 (48.8%) identify as men. Among generations, 18 (21.7%) are Generation X, 21 (25.3%) are Generation Y, and 44 (53%) are Generation Z.

Regarding religion, 35 (40.7%) identify as Christianity, 31 (36.0%) as Agnostic, 2 (2.3%) as Hinduism, 2 (2.3%) as Buddhism, 2 (2.3%) as Judaism, 7 (8.1%) as not religious, 5 (5.8%) as spiritual, and 2 (2.3%) as Atheist. In terms of race/ethnicity, the majority are White (73 individuals, 84.9%), followed by 4 (4.7%) who identify as Asian, 4 (4.7%) as Hispanic or Latino, 3 (3.5%) as Black or African American, 1 (1.2%) as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and 1 (1.2%) as American Indian or Alaska Native. In student/faculty status, 51 (59.3%) are students, and 35 (40.7%) are faculty/staff members at the University of Utah.

For types of social influence, normative social influence is reported by 48 (55.8%) participants, while informational social influence is reported by 69 (80.2%) participants. Additionally, 58 (67.4%) participants reported seeking help for mental health issues (exhibiting help-seeking behavior), while 18 (20.9%) did not, with 10 missing responses.

Skewness

The distribution of our sample data for age was found to be positively skewed, with a skewness statistic of 1.17 (SE = 0.26), indicating a tail towards lower values (where skewness is a measure of asymmetry of the probability distribution of a variable). Skewness for comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends (-.72, SE = 0.27), perceived mental health stigma within the community (-3.07, SE = .27), ASI (-0.87, SE = 0.26), and general social influence (-0.10, SE = 0.26) were negative, indicating a tail toward lower values. This skewness suggests that the data are not normally distributed, which may influence the interpretation of parametric statistical tests. The sample under study exhibits a balanced distribution in terms of gender, with 51.2% identified as women and 48.8% as men. However, 84.9% of the sample identifies as White, indicating a predominant racial demographic. A nearly balanced distribution was exemplified through student/faculty status, with 59.3% participants identifying as students and 40.7% identifying as faculty. Lastly, the percentages for generation (21.7% Generation X, 25.3% Generation Y, 53% Generation Z) shows a slightly uneven distribution.

Mental Health Stigma and Help-Seeking Behavior

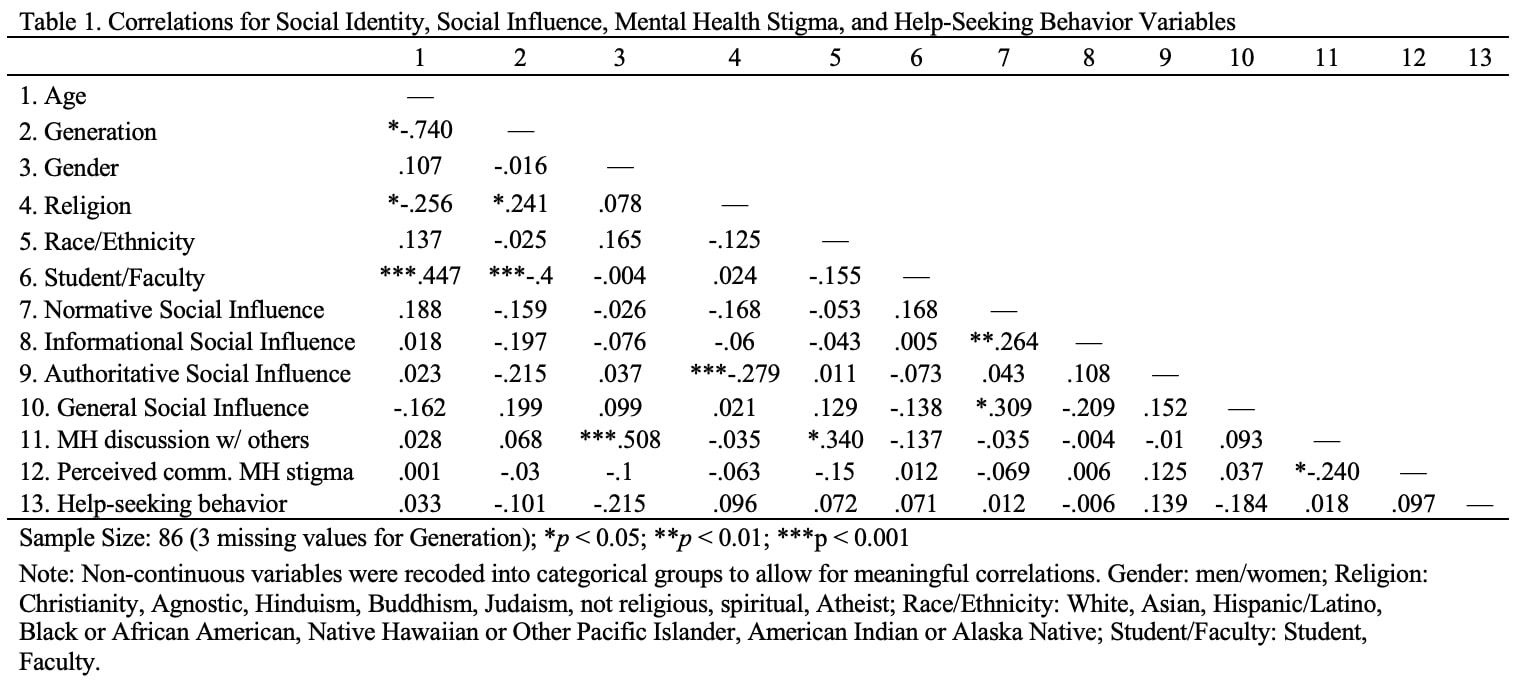

The initial analysis aimed to examine the correlation between comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends along with perceived mental health stigma within the community and help-seeking behavior using a bivariate 2-tailed Pearson correlation as reported in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, the correlation coefficient indicated no significant correlation at the 0.05 level between comfort levels of discussing mental health challenges with family and friends and help-seeking behavior (r (73) = 0.02, p = 0.88) and perceptions of mental health stigma within the community and help-seeking behavior (r (72) = 0.10, p = 0.41). However, a statistically significant negative correlation at the 0.05 level between comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends and perceived mental health stigma within the community r (72) = -0.24, p = 0.04) was revealed as predicted.

Social Identity and Mental Health Stigma/Help-Seeking Behavior

Aspects of social identity were analyzed using bivariate 2-tailed Pearson correlations between comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceived mental health stigma within the community, and help-seeking behavior as a first step as indicated in Table 1. The analysis between age with comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends (r (73) = 0.03, p = 0.81), perceived mental health stigma within the community (r (72) = 0.001, p = 0.99), and help-seeking behavior (r (74) = 0.03, p = 0.77) revealed no significant correlations. To test age groups, an independent samples t-test was run at the 0.05 level revealing no significant differences between younger adults (18-30) and older adults (31-64) with comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends (t (73) = -0.42, p = 0.53), perceived mental health stigma within the community (t (72) = -0.63, p = 0.43), and help-seeking behavior (t (74) = -0.47, p = 0.52). Additionally, no significant correlations were found between comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceived mental health stigma within the community, and help-seeking behavior with generation. Given that race/ethnicity is not a continuous variable, it was recoded into categorical groups to allow for meaningful comparisons. However, both gender and race/ethnicity showed statistically significant positive correlations with comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to assess the differences in comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends among different race/ethnicity groups. However, the ANOVA yielded no statistically significant result among the means of comfort levels, F (7, 74) = 1.22, p = 0.05. This indicates that there were no significant differences in comfort levels across the various race/ethnicity groups. Following the ANOVA, a post-hoc test, specifically a Bonferroni correction, was employed to compare the means of comfort levels between specific race/ethnicity groups further revealing no difference in means for racial and ethnic groups, ensuring accurate identification and interpretation of any potential differences or lack thereof among the groups.

For gender and comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, the correlation coefficient revealed r (73) = 0.51, p < 0.001, indicating that women may feel more at ease discussing mental health issues with their family and friends compared to men within the sample. To further describe this indication between gender and comfort levels discussing mental challenges with family and friends, an independent samples t-test revealed a statistically significant difference (t (73) = -5.04, p < 0.001; d = 1.17) with men reporting higher levels of discomfort discussing mental health challenges with family and friends (M = 4.33, SD = 0.93, n = 39) compared to women (M = 2.97, SD = 1.38, n = 36).

An independent samples t-test at the 0.05 level analyzed differences among means between students (M = 3.6, SD = 1.35, n = 42) and faculty (M = 3.79, SD = 1.36, n = 33) of comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends and found no statistically significant difference (t (73) = – 0.61, p = 0.27; d = 1.35). Another independent samples t-test at the 0.05 level analyzed the difference among means between students (M = 3.22, SD = 1.06, n = 41) and faculty (M = 2.88, SD = 1.43, n = 33) and perceptions of mental health stigma within the community (t (72) = 1.18, p = 0.12; d = 1.23) and also found no statistically significant difference. Lastly, an independent samples t-test at the 0.05 level revealed no statistically significant difference (t (74) = -0.10, p = 0.46; d = 0.43) between students (M = 1.23, SD = 0.43, n = 43) and faculty (M = 1.24, SD = 0.44, n = 33) exhibiting help-seeking behavior. The findings indicate that students and faculty in the sample share similar levels of comfort discussing mental health challenges, perceptions of mental health stigma within the community, and personal experiences of mental health stigma.

Social Identity and Social Influence

Bivariate 2-tailed Pearson correlations among variables of social identity were run as indicated in Table 1 to examine if there were statistically significant relationships between different variables of social identity, providing insights into the interplay and potential influences among these factors within the study population. Generation provided statistically significant correlations with religion at the 0.05 level (r (81) = 0.24, p = 0.03) suggesting that individuals from certain generations are more likely to identify with specific religious groups than others. As expected, student/ faculty status was significantly correlated with age (r (84) = 0.45, p < 0.001) and generation (r (81) = -0.4, p < 0.001).

Further bivariate 2-tailed Pearson correlations were run between variables of social identity (age, generation, gender, race/ethnicity, religion, student/faculty) and types of social influence (normative, informational, authoritative, general) as reported in Table 1. To clarify, religion was categorically coded based on participant’s self-reported religious affiliations or beliefs. A statistically significant negative correlation was found at the 0.05 level between religion r (84) = -0.28, p < 0.001 and authoritative social influence. An independent samples t-test using only participants identifying as Christian or Agnostic revealed a statistically significant difference (t (64) = 3.66, p < 0.001) with Christians reporting higher levels of authoritative social influence (M = 4.26, SD = 0.95) compared to (M = 3.26, SD = 1.26; d = 1.11) suggesting that Christians exhibit a stronger inclination towards such influence compared to Agnostics within the sample. Additionally a post-hoc test using the Bonferroni correction was employed to account for multiple comparisons. This correction reduces the likelihood that multiple comparisons with a particular error rate will yield at least one unreliable finding.

Social Influence

Bivariate 2-tailed Pearson correlations were run to see if types of social influence to examine the extent to which different types of social influence variables (normative, informational, authoritative, and general) are correlated, providing insights into the associations of various forms of social influence.

Statistically significant correlations were found between normative social influence and informational social influence at the 0.05 level, r (84) = 0.26, p = 0.01, along with normative social influence and general social influence at the 0.05 level, r (84) = 0.31, p = 0.04.

Discussion

Mental Health Stigma and Help-Seeking Behavior

The goal of this study was to explore the association between social influence and social identity, with a specific focus on how these factors are associated with attitudes toward mental health, mental health stigma, and help- seeking behavior across different demographic groups. As expected, analyses supported the idea that individuals’ comfort level discussing mental health challenges with their family and friends and their perception of mental health stigma in their community are negatively correlated, which is consistent with previous literature (Cheng et al., 2018; Rüsch et al., 2014; Shefer et al., 2012). Thus, this finding may suggest that those who feel more at ease discussing mental health topics with their family and friends are likely to perceive lower levels of stigma associated with mental illness or help-seeking behaviors within their community (Cheng et al., 2018). Further, this correlation could reflect the influence of social support and acceptance, as individuals who experience greater support from their family and friends may view mental health issues as less stigmatized in their broader community (Rüsch et al., 2014).

The absence of a correlation between comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends and help-seeking behavior did not support the initial hypothesis. Moreover, the absence of a correlation between the perception of stigma within the community and help-seeking behavior also did not support our initial hypothesis. Previous research has shown correlations between mental health stigma and help-seeking behavior, regardless of whether mental health stigma shows a positive or negative correlation with help-seeking behavior, which does not align with our findings (Cheng et al., 2018; Gaddis et al., 2018; Juvrad & Rennels, 2017; Klik et al., 2018; Michaels et al., 2015; Shefer et al., 2012). The unexpected findings could be because the sample included only students or faculty from the University of Utah, where student/faculty status did not exhibit any correlations with comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceptions of mental health stigma in the community, and help-seeking behavior.

Social Identity, Mental Health Stigma, and Help-Seeking Behavior

The absence of statistically significant correlations between age with help- seeking behavior, comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, and perceptions of mental health stigma in the community diverged from the initial hypothesis of the study. Despite the expectation that age would exhibit meaningful correlations with these variables, the data did not substantiate these anticipated correlations. Further, age groups (younger adults ages 18-30 and older adults 31-64) also did not exhibit meaningful correlations with comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceptions of mental health stigma, and help-seeking behavior, which also did not support our initial hypothesis that younger adults would exhibit higher levels of mental health stigma and lower levels of help-seeking behavior. While age has been postulated to impact individuals’ attitudes toward mental health stigma (Bradbury, 2020), and help-seeking behavior in previous research (Corey et al., 2008; Myers & Twenge, 2022), the lack of significant correlations in this study suggests age alone may not be a strong predictor of these outcomes within our sample, even when stratifying participants into different age groups.

In addition to age, gender emerged as another potential influencing factor in attitudes toward mental health stigma and help-seeking behavior. The initial hypothesis that gender would produce a significant result with comfort level discussing mental health challenges with family and friends and/or perceptions of mental health stigma within the community aligned with the result that men have higher levels of discomfort discussing mental health challenges among family and friends. This may be aligned with research indicating that men have said that they could not speak with their parents, specifically their fathers because they would not “get it” (Herron et al., 2020). Further, this aligns with previous research on how seeking help for mental health issues may be viewed as a deviation from traditional gender roles and could lead to feelings of shame or isolation (Buffel et al., 2014) along with stereotypes of masculinity reflected by observations of men in social roles (Caraballo, 2023; Diekman & Eagly, 2000; Juvrud & Rennels, 2016).

However, the initial hypothesis that specific races/ethnicities would show differences in comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceptions of mental health stigma within the community, and help- seeking behavior was not supported, suggesting potential limitations in the sample’s diversity or representation. While some literature supports this finding (Jimenez et al., 2013), other literature supports our result saying that these attitudes and perceptions are associated with other demographic constructs and not race/ethnicity (Abdullah & Brown, 2011). In additional studies, there was no support for lower use of mental health services or higher mental health stigma by some ethnic minority groups (Kapadia, 2023) (Tran, 2021).

In further analysis of the results concerning variables of social identity and both aspects of mental health stigma and help-seeking behavior, no significant correlations were observed in association with generation among comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceptions of mental health stigma in the community, and help-seeking behavior, though no hypothesis was formed about this. However, regarding student/faculty status, no differences were found among levels of comfort discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceptions of mental health stigma within the community, and help-seeking behavior. The findings did not align with the initial hypothesis proposing that both students and faculty would hold negative views regarding help-seeking behavior, contrary to previous research (Chen et al., 2016; Gaddis et al., 2018), Michaels et al., 2015).

Moreover, the hypothesis suggesting differences in scores of comfort levels when discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, as well as variations in perceptions of mental health stigma within the community between students and faculty, was not supported by the data, contradicting previous research on the same concepts (Chen et al., 2016; Gaddis et al., 2018; Michaels et al., 2015). Since only University of Utah students and faculty could participate in this research, this could suggest that the University of Utah possesses specific institutional characteristics, such as a strong emphasis on mental health awareness and support services. The presence of campus resources such as counseling centers, mental health outreach programs, and student-led initiatives may contribute to a more supportive environment for mental health and help-seeking behavior among both students and faculty which is consistent with the broader implications of other research associated with campus culture serving as an important role in personal mental health treatment beliefs (Chen et al., 2016).

Social Identity Correlations: Age, Generation, Student/Faculty Status, Religion

In our study, age demonstrated correlations with generation, student/faculty status, and religion. Age, age groups, student/faculty status, and generation being correlated could be expected given that they are interconnected demographic variables. Further, generation showed statistically significant correlations with student/faculty status, which also may make sense given that age is associated with generation and individuals within certain generational cohorts are often found among students or faculty members. Unexpectedly, there was a positive correlation between generation and religion, indicating that individuals from different age groups tend to have consistent differences in their religious beliefs or affiliations. This suggests that there may be notable connections between an individual’s religious beliefs, practices, or affiliations and their stage in the lifespan, (Manoiu et al., 2022). As an alternate explanation, this correlation could imply that religious attitudes, values, or behaviors undergo shifts or developments as individuals progress through different life stages, where people in older generations may be more likely to engage in religious or spiritual practices (Manoiu et al., 2022).

Social Identity and Social Influence Dynamics

The initial hypothesis that specific aspects of social identity, such as generation, gender, race/ethnicity, religion, and student/faculty status, are directly tied to self-reported types of social influence was partially supported. The negative correlation between religious affiliation and obedience to authority figures (authoritative social influence) could suggest that individuals who identify with certain religious beliefs or affiliations, such as Christianity, may hold more negative attitudes toward obeying authority figures. This may be because religious priming has been found to facilitate compliance to authority figures requests and conformity (Saroglou et al., 2009; Van Cappellen et al., 2011).

Further, Christians reported higher levels of authoritative social influence compared to Agnostics. The finding that Christians reported higher levels of authoritative social influence compared to Agnostics further exhibits the potential influence of religious affiliation on attitudes toward authority within social contexts, which could suggest that individuals who identify as Christians may be more inclined to perceive authoritative figures or sources of influence as credible and persuasive compared to those who identify as Agnostics (Saroglou et al., 2009; Van Cappellen et al., 2011). The alternative explanation for this correlation may show that individuals’ pre-existing attitudes toward authority guide their choice of religious affiliation. Despite limited research on the topic, individuals who tend to be more susceptible to authoritative sources of influence may have a higher likelihood of identifying as Christians or with religious belief systems in general (Saroglou et al., 2009; Van Cappellen et al., 2011).

The correlation between normative social influence and informational social influence supports the initial hypothesis that there exists a positive correlation between normative and informational social influence. However, our initial hypothesis that normative and informational social influence will demonstrate a correlation with authoritative social influence was unsupported. The correlation between normative social influence and informational social influence may suggest that individuals who are more sensitive to normative influence may also be more likely to seek out and rely on informational cues from others (Heinzein & Goodfriend, 2019; Mallinson & Hatemi, 2018; Werner et al., 2008). This connection can be understood within the framework of social psychology, where individuals often engage in conformity behaviors not only to fit in with the group but also to gain information and clarity about the situation (Deutsch & Gerard, 1954).

The correlation between normative social influence and general social influence, which is a person’s self-recognition of their sensitivity to social influence, provides insights into individuals’ perceptions of their own susceptibility to social pressures and their tendency to conform to group norms. This finding, though unanticipated, could suggest that individuals who perceive themselves as more sensitive to social influence are also more likely to conform to group norms to gain social acceptance or approval (Deutsch & Gerard, 1954; Mallinson & Hatemi, 2018). Additionally, individuals who perceive themselves as sensitive to social influence may experience greater pressure to conform to group norms, as they are more aware of the potential consequences of deviating from those norms (Mallinson & Hatemi, 2018).

Limitations

While some findings align with previous research, further investigation is necessary to fully understand the multifaceted dynamics between social influence, social identity, mental health stigma, and help-seeking behavior. While our study reaffirms the established relationship between comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends and perceptions of stigma, it presents unexpected findings regarding the absence of correlations with help-seeking behavior. Reliance on correlational data introduces inherent limitations in establishing causality, and the lack of significant associations between age, gender, race/ethnicity, and help-seeking behavior contradicts prior research.

The study’s narrow focus on a specific university population may limit its applicability to broader societal dynamics, potentially compromising external validity. Nonetheless, this study represents a crucial step in integrating research on social identity, social influence, mental health stigma, and help-seeking, offering promising insights into factors (such as religion or gender) associated with social influence and social identity within the context of mental health stigma.

Although we implemented multiple different participant recruitment strategies, most participants in the study were White, early 20-year-olds. It is important to consider that the absence of a difference of means comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, perceptions of mental health stigma within the community, and help-seeking behavior among racial/ethnic groups may stem from the overrepresentation of white participants relative to non-white participants in our sample, which might have reduced the statistical power to discern noteworthy variances among racial/ethnic groups.

Further, the sample size of the study was relatively small. Such homogeneity within the sample limits generalizability. Given the perception and experience of social identity, social influence, stigma, and help-seeking behavior are different in various cultures, the results should be interpreted with this limitation in mind. For this reason, among others, replication is key, and future studies should be conducted among larger and more heterogeneous samples.

Another limitation is the novelty of the survey questions. The absence of prior testing means that the reliability and validity of these questions remain unknown. Furthermore, the utilization of different response formats, such as Likert scales and yes/no responses, adds complexity to data analysis and interpretation. While Likert scales offer a nuanced understanding of participants’ attitudes and perceptions, yes/no responses provide binary information that may lack granularity.

Moreover, these questions may be subject to varying interpretations. For instance, the inquiry regarding individuals’ perceptions of mental health stigma within their community could encompass diverse interpretations. Participants might define their community as comprising close family and friends, their school or workplace community, or even their city’s population. Similarly, the question concerning comfort levels in discussing mental health challenges with family and friends could be understood differently depending on individuals’ definitions of family and friends.

Another limitation of this study was the decision of certain participants to refrain from answering the survey questions concerning mental health stigma and help-seeking behavior. Specifically, out of our original sample of 86 participants, only 75 reported their comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, 74 expressed their perceived mental health stigma within the community, and 76 expressed their engagement in help- seeking behavior. Notably, these participants responded to all other inquiries. This selective participation suggests a potential prioritization of less sensitive topics and discomfort with directly addressing mental health stigma and help- seeking behavior.

Future Research

Exploring gender differences in discussing mental health challenges with family and friends is another area deserving of analysis. While previous research has examined differences between men and women in this context, further investigations can delve into the underlying reasons for men’s discomfort in discussing mental health challenges with family and friends related to other aspects of their social identity. Specifically, research could delve into how other aspects of men’s social identity, such as cultural background, socioeconomic status, occupational roles, or adherence to traditional masculine norms, influence their attitudes and behaviors surrounding mental health discussions. Further, these aspects of men’s social identity and their attitudes and behaviors surrounding mental health discussions could be investigated through the lens of social influence. Understanding the sociocultural norms, expectations, and psychological factors influencing men’s attitudes toward mental health discussions can inform targeted interventions aimed at promoting open dialogue and support-seeking behaviors among groups of men.

Additionally, it would be valuable to include an exploration of mental health stigma and help-seeking behavior among nonbinary and atypical presentations of gender. This aspect was a limitation due to the relatively small sample size in our study. Understanding the unique challenges and experiences of nonbinary individuals and those with atypical gender presentations can provide insights into developing more inclusive and effective mental health support strategies.

Investigating how stigma and societal expectations impact help-seeking behaviors among these groups can contribute to the development of interventions that address their specific needs and promote a more inclusive approach to mental health support.

The exploration of the correlation between authoritative social influence and religion presents a multifaceted area suitable for in-depth investigation. By conducting systematic inquiries into how authoritative social influence manifests within different religious affiliations, future research could unveil dynamics that shape belief systems, behaviors, and social interactions within these religious communities. Furthermore, exploring the correlations between religion, generation, and age can provide insights into how religious beliefs and practices evolve across the lifespan as there seems to be a lack of research on this subject. Building on our findings related to diverse identities, it would be compelling to examine the association between social influence and mental health stigma within multiple, various religious belief systems. A more diverse and expanded sample size could offer clarity on whether similar associations exist across different religious contexts.

Further research on understanding how normative and informational social influence interact in shaping attitudes toward mental health stigma and help- seeking behavior can inform the development of nuanced models and interventions aimed at challenging stigma and promoting positive help-seeking behaviors. Exploring individuals’ awareness and sensitivity to social influence, especially concerning their ability to recognize it within themselves, offers another avenue for research to understand how external factors, such as peer pressure, media portrayal, or cultural norms influence self-perceptions, behaviors, and self-awareness in decision-making. Finally, exploring the association between perceived mental health stigma within communities and individuals’ comfort levels in discussing mental health challenges with their social networks can reveal socio-cultural dynamics impacting help-seeking behaviors, which may inform interventions aimed at destigmatizing mental health issues and fostering supportive environments for help-seeking.

Conclusion

Overall, the findings presented in the current study are among the first to explore the role of associations among aspects of social identity, social influence, perceptions about mental health stigma in the community, comfort levels discussing mental health challenges with family and friends, and help-seeking behavior. The findings demonstrate that both social identity and social influence are important factors that are associated with each other. Our findings demonstrated that religious affiliation may play a role in how people respond to social influence. For example, individuals with certain religious beliefs, such as Christians, may be more likely to obey authority figures. This correlation offers new insights into how religious beliefs might shape individuals’ responses to authority within social contexts.

Further, findings show that men are less comfortable discussing mental health challenges with family and friends compared to women. Men reported lower levels of comfort discussing mental health issues with family and friends, aligning with previous research suggesting barriers due to traditional gender roles and stereotypes of masculinity. This suggests that the presence of stigma and discomfort surrounding mental health discussions can hinder the willingness to reach out for help or support from trusted social groups, even though there was no correlation between help-seeking behavior and men.

Furthermore, the findings that men reported higher levels of discomfort discussing mental health challenges highlight the critical need for targeted interventions aimed at reducing stigma and fostering open dialogue about mental health within communities, thereby promoting greater accessibility to support resources and fostering a more supportive environment for individuals experiencing mental health challenges. Accounting for and continuing to explore aspects of social identity and social influence through a lens of mental health awareness, understanding, and support may provide new insights about combatting mental health stigma and motivations to seek treatment.

References

Abdullah, T., & Brown, T. L. (2011). Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 934–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003

Ahmedani B. K. (2011). Mental Health Stigma: Society, Individuals, and the Profession.

Journal of social work values and ethics, 8(2), 41–416.

Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. Groups, leadership and men. Carnegie Press.

Bradbury, A. (2020). Mental Health Stigma: The impact of age and gender on attitudes.

Community Mental Health Journal, 56(5), 933–938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597- 020-00559-x

Castrellon, J. J. (2023, September 8). Adult age-related differences in susceptibility to social conformity pressures in self-control over daily desires. OSF. https://osf.io/4kf3a/

Chen, J. I., Romero, G. D., & Karver, M. S. (2016). The relationship of perceived campus culture to mental health help-seeking intentions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(6), 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000095

Cheng, H., Wang, C., McDermott, R. C., Kridel, M. M., & Rislin, J. L. (2018). Self-Stigma, mental health literacy, and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling and Development, 96(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12178

Choudhry, F. R., Mani, V., Ming, L. C., and Khan, T. M. (2016). Beliefs and perception about mental health issues: a meta-synthesis. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Volume 12, 2807–2818. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s111543

Corrigan, P. W., Druss, B. G., and Perlick, D. A. (2014). The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15(2), 37-70.

Deutsch, M., and B. Gerard, H. (1954). A Study of Normative and Informational Social Influences Upon Individual Judgement. Research Center for Human Relations.

Diekman, A. B., & Eagly, A. H. (2000). Stereotypes as dynamic constructs: women and men of the past, present, and future. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(10), 1171–1188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167200262001

Eisenberg, D., Downs, M. F., Golberstein, E., & Zivin, K. (2009). Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Medical Care Research and Review, 66(5), 522–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558709335173

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Prentice-Hall. Guimond, S. (1997). Attitude Change During College: Normative or Informational Social

Influence? Social Psychology of Education, 2(3/4), 237–261. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009662807702

Heinzen, T. E., and Goodfriend, W. (2019). Social Psychology.

Herron, R., Ahmadu, M., Allan, J. A., Waddell, C., & Roger, K. (2020). “Talk about it:” changing masculinities and mental health in rural places? Social Science & Medicine, 258, 113099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113099

Hogg, M. A., Abrams, D., and Brewer, M. B. (2017). Social identity: The role of self in group processes and intergroup relations. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 20(5), 570–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217690909

Juvrud, J., & Rennels, J. L. (2016). “I Don’t Need Help”: Gender Differences in how Gender Stereotypes Predict Help-Seeking. Sex Roles, 76(1–2), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0653-7

Kapadia, D. (2023). Stigma, mental illness & ethnicity: Time to centre racism and structural stigma. Sociology of Health & Illness, 45(4), 855–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467- 9566.13615

Klik, K. A., Williams, S. L., and Reynolds, K. J. (2018). Toward understanding mental illness stigma and help-seeking: A social identity perspective. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 35(7), 524-547.

Mackie, D. M., Smith, E. R., and Ray, D. G. (2008). Intergroup Emotions and Intergroup Relations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(5), 1866–1880. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00130.x

Mallinson, D. J., and Hatemi, P. K. (2018). The effects of information and social conformity on opinion change. PLOS ONE, 13(5), e0196600. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196600

Manoiu, R., Hammond, N. G., Yamin, S., & Stinchcombe, A. (2022). Religion/Spirituality, Mental Health, and the Lifespan: Findings from a Representative Sample of Canadian Adults. Canadian Journal on Aging, 42(1), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0714980822000162

Myers, D. G., Twenge, J. M. (2022). Social Psychology. McGraw-Hill Companies.

Rüsch, N., Brohan, E., Gabbidon, J., Thornicroft, G., & Clément, S. (2014). Stigma and disclosing one’s mental illness to family and friends. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (Print), 49(7), 1157–1160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0871-7

Saroglou, V., Corneille, O., & Van Cappellen, P. (2009). “Speak, Lord, your servant is listening”: religious priming activates submissive thoughts and behaviors. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 19(3), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508610902880063

Shefer, G., Rose, D., Nellums, L. B., Thornicroft, G., Henderson, C., & Evans-Lacko, S. (2012). ‘Our community is the worst’: The influence of cultural beliefs on stigma, relationships with family and help-seeking in three ethnic communities in London. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(6), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764012443759

Smith, J., Smith, J., McLuckie, A., Szeto, A. C. H., Choate, P., Birks, L. K., Burns, V., & Bright, K. (2022). Exploring Mental Health and Well-Being Among University Faculty Members: A Qualitative study. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 60(11), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20220523-01

Tran, A. G. T. T. (2021). Race/ethnicity and Stigma in Relation to Unmet Mental Health Needs among Student-athletes. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy (Online), 36(4), 392–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2021.1881859

Van Cappellen, P., Corneille, O., Cols, S., & Saroglou, V. (2011). Beyond mere compliance to authoritative figures: religious priming increases conformity to informational influence among submissive people. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion/the International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 21(2), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2011.556995

Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., and Hackler, A. H. (2007). Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 40-50.

Werner, C. M., Sansone, C., and Brown, B. B. (2008). Guided group discussion and attitude change: The roles of normative and informational influence. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.10.002