College of Social and Behavioral Science

167 Maternal Sensitivity and Infant Behavior in the Still-Face Paradigm: A Cross-Cultural Comparison between Hispanic and White/Non-Hispanic Mother-Infant Dyads

Andrew Parker and Lee Raby

Faculty Mentor: Lee Raby (Psychology, University of Utah)

Background

The Still Face Paradigm was designed by Tronick, Als, Adamson, Wise, and Brazelton (Tronick, E., Als, H., Adamson, L., Wise, S., & Brazelton, T. B, 1978). The Still Face Paradigm consists of three different interactions between the child and mother: a baseline episode (in which the mother and infant watch a 2-minute video together), the still face episode (in which the mother becomes unresponsive, keeping a neutral facial expression), and the reunion episode (in which the mother interacts normally with the baby). The order of the episodes is baseline, still face, and reunion. The still-face has “been found to evoke marked changes in infant behavior, now known as the still- face effect” (Mesman, van Ijzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2009). The still-face effect involves infants exhibiting reduced positive affect and increased negative affect during the still face episode compared to the baseline episode. There is also a carry-over effect in the reunion, which also involves reduced infant positive affect and increased negative affect when compared to the baseline (Mesman, van Ijzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2009). However, there tends to be a partial recovery during the reunion episode.

Not all infants respond the same way to the Still Face Paradigm though. A particularly potent predictor of these individual differences is the degree to which the mothers respond to their infants’ signals in a timely and appropriate manner (i.e., sensitively). Indeed, meta-analyses of the Still Face Paradigm have found that higher maternal sensitivity was a predictor for more positive affect from the infant during the still face (Mesman, van Ijzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2009).

The Still Face Paradigm has been used for various purposes in dozens of studies, but there are still many areas of research using the Still Face Paradigm that need to be examined further. One of those areas is examining the influence of potential cultural differences of the mother and baby.

Research findings suggest that culture influences infant emotion expression (Li et. al, 2019). For example, a Still Face Paradigm study in Asia displayed different results in regard to the still-face effect when compared to infants from Western cultures (Li et. al, 2019). The infants in the Asian cultures tended to have an increase in negative affect throughout each episode with no recovery (Li et. al, 2019).

In addition, various studies have found that there are cultural differences with maternal responsiveness to children’s signals (Lowe et. al, 2016). For example, Lowe and colleagues (2016) report Hispanic mothers living in the United States engaged more in attention seeking touch during the Still Face Paradigm than non-Hispanic mothers, which significantly increased infant negative affect compared to playful touch. The most effective kind of touch with increasing child positivity after stressors was found to be playful touch (Lowe et. al, 2016). Results from this study supported that the kind of touch an infant receives plays a large role in infant emotional regulation, and that maternal- infant touch varies across different cultures (Lowe et. al, 2016). These examples of cross-cultural differences could potentially influence results from the Still Face Paradigm procedure.

Minimal research using the Still Face Paradigm has been conducted with the Hispanic population living in the United States. The White Hispanic population is currently the second fastest growing population in the United States with a growth of 1.24% in between 2020 and 2021. In contrast, the White/non-Hispanic population has declined in growth by 0.03% during that time (Harris, 2022). Utah has become increasingly racially and ethnically diverse, with a 3.1% increase in minority population from 2020 to 2021 (Harris, 2022). The second-largest racial population in Utah is the White Hispanic population, which increased by 3% in 2020 to 2021 and accounted for 63% of the minority growth in Utah (Harris, 2022). The presence and continued increase of Hispanic population indicate an increased need for research related to this population.

Understanding how maternal sensitivity and infant behavior may differ across cultures is important to be able to better understand child development and how to create effective intervention and prevention programs (Huang, Caughy, Genevro & Miller, 2005). Understanding maternal sensitivity is also important in order to be able to “enhance maternal sensitivity and to maximize the developmental potential of infants” (Shin, Park, Ryu & Seomun, 2008).

Aims of the Current Study

The purpose of this study is to examine three research questions. The first is whether there are differences in infant behavior during the Still Face Paradigm for White/Non-Hispanic and Hispanic infants. The second question is whether there are differences in levels of maternal sensitivity during the free-play interactions for Hispanic and White/Non-Hispanic mothers. The third question is if the associations between maternal sensitivity and infant behavior differs for Hispanic and White/Non- Hispanic mother-infant dyads.

Design Plan Study Type

- Observational study

Blinding

- No blinding is involved in this study.

- This was an observational study, so participants were not assigned to treatment groups. Individuals who coded maternal sensitivity were blind to information about infant behavioral responses to the SFP and vice versa. Both groups of coders were blind to information about infant race/ethnicity other than what could be inferred from the video-taped observations. In addition, all individuals who collected the data and coded the observations were blind to the aims and hypotheses of the current study.

Study Design

Mother-infant pairs participated in the Still-Face Paradigm when infants were approximately 7- months-old. Infant behavior was observed and coded during the Still-Face Paradigm. Afterwards, mothers and infants were observed during a free-play interaction, and maternal parenting quality was rated. The race and ethnicity of the infant was reported by the mother by using an online questionnaire.

Sampling Plan

Data collection procedures

The original sample size was 385. This study is a longitudinal cohort where mothers were recruited to the study when they were pregnant. This study is focused on the subsample of mother-infant dyads who participated when the infant was 7-months old. During the 7-month visit, the mother-child dyad participated in the Still-Face Paradigm and a 15-minute free-play.

Sample size:

Participants must: (1) Have maternal parenting quality ratings, (2) have codes for infant behavior during the play, still-face, and reunion episodes of the Still-Face Paradigm, and (3) infants must be either White/non-Hispanic or Hispanic in race/ethnicity.

Sample size rationale

Power analysis was used to determine the original sample size of 385. The current sample size is the subset of participants who have the necessary data to answer these research questions.

Variables

Manipulated variables

– No manipulated variables

Measured variables

Precisely define each variable that you will measure. This will include outcome measures, as well as any measured predictors or covariates.

• Infant race/ethnicity: Mothers were provided an online questionnaire and asked a series of questions about the infant’s race and ethnicity. This included a yes/no question about if the infant was Hispanic/Latino or not. A separate question asked if the baby was White, Asian, etc. These questions identified infants who White/non-Hispanic and Hispanic. All other participants were excluded from this research.

• Maternal sensitivity: Maternal sensitivity was rated based on mother-infant interactions during free-play. The dyadic play sessions occurred at the end of the visit where the mother and her child played together for 10 minutes with toys provided by the research assistants. Interactions were recorded and were coded later using four, 5-point scales capturing maternal sensitivity to non-distress, intrusiveness, detachment, and positive regard. These scales were adapted from the Observational Record of the Caregiving Environment and (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1996).

• Infant behavior: Infant behaviors during each of the 2-minute episodes of the Still Face Paradigm were coded on a second-by-second basis using Infant and Caregiver Engagement Phases (ICEP; Weinberg & Tronick, 1999) coding system. The ICEP includes the 8 infant codes: (1) Negative Engagement, (2) Protest, (3) Withdrawn, (4) Object/Environment

Engagement, (5) Social Monitor, (6) Social Positive Engagement, (7) Sleeping, and (8) Unscorable. Coders used Noldus’s The Observer to code the videos. Coders were trained over the course of 4 weeks by coding 16 Still Face cases with the goal of achieving an average of 80% reliability when compared to a highly reliable coder. Coders who achieved this goal were permitted to code new data.

Indices:

• Maternal behavior: a composite measure representing overall maternal sensitivity during the free-play interactions will be created by averaging the five ratings of maternal behavior during the reunion episodes (after reverse scoring maternal intrusiveness and detachment).

• Infant behavior: The number of times that each code is assigned to an infant during each episode will be summed such that the potential range will be 0-120 per code per episode. These sum scores will then be divided by 120 minus the number of Unscorable codes for each episode. This will result in a variable representing the percentage of time each code was assigned within each episode. The codes for Negative Engagement, Protest, and Withdrawn will be summed within each episode to create a composite measure of infant distress during each of the three episodes of the SFP. Likewise, the codes for Social Monitor and Social Positive Engagement will be summed within each episode to create a composite measure of infant sociability during each of the three episodes of the SFP.

Analysis Plan

Statistical models:

• In order to address whether there are differences in infant behavior during the Still Face Paradigm for White/Non-Hispanic and Hispanic infants (Aim 1), a repeated-measures ANOVA will be used.

o Infant behavior is the dependent variable.

o Infant race is the independent variable.

• In order to address whether there are differences in levels of maternal sensitivity during the free-play interactions for Hispanic and White/Non-Hispanic mothers (Aim 2), a one-way ANOVA test will be used.

• In order to address whether the associations between maternal sensitivity and infant behavior differ for Hispanic and White/Non-Hispanic mother-infant dyads (Aim 3), two repeated measure ANOVAs will be conducted, one for White/non- Hispanic mother-infant dyads and one for Hispanic mother-infant dyads. For each, sensitivity will be a continuous predictor variable and infant behavior during the three episodes of the SFP will be the outcome variable. The results of the two ANOVAs will be compared.

Inference criteriaFor all analyses, a criterion of p < .05 (two-tailed test) will be used to determine if the results are significantly different from those expected if the null hypotheses were correct.

Data exclusion

No data will be excluded.

Missing data

Participants must have complete data for the variables used in the analyses.

Research Questions

1. Do White/Non-Hispanic and Hispanic infants have different behaviors during the Still-Face Paradigm?

2. Are there differences in levels of maternal sensitivity during the free-play interactions for Hispanic and White/Non-Hispanic mothers?

3. Is the association between maternal sensitivity and infant behavior different for Hispanic and White/Non-Hispanic mother-infant dyads?

Methods

Participants (109 mother-infant dyads)

– 24 infants were Hispanic

– 85 infants were White/Non-Hispanic Measures

– Maternal Sensitivity: Rated on a 5-point scale based on mother-infant interactions during a 10- minute free-play interaction with toys.

– Infant Behavior: Distress was coded on a second-by-second basis and was averaged for each of the 2-minute episodes of the Still-Face Paradigm.

Results

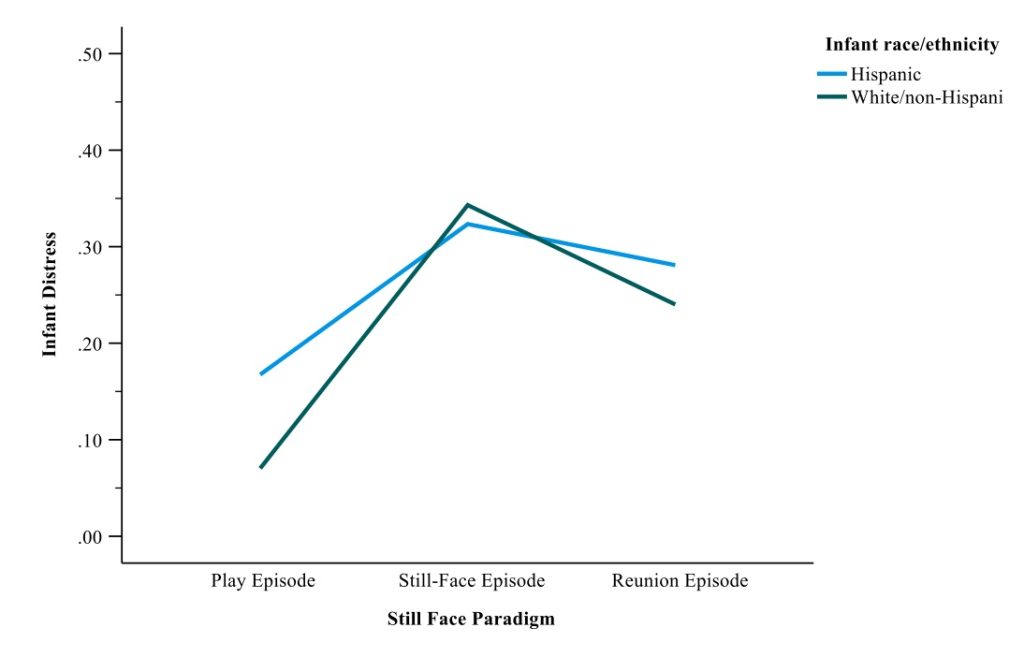

Question 1: Infant behavior during the Still-Face Paradigm

– A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a quadratic change in infant distress during the Still- Face Paradigm (p < 001).

– There was not a significant difference based on infant race/ethnicity.

– See Graph 1: Question 1 Results.

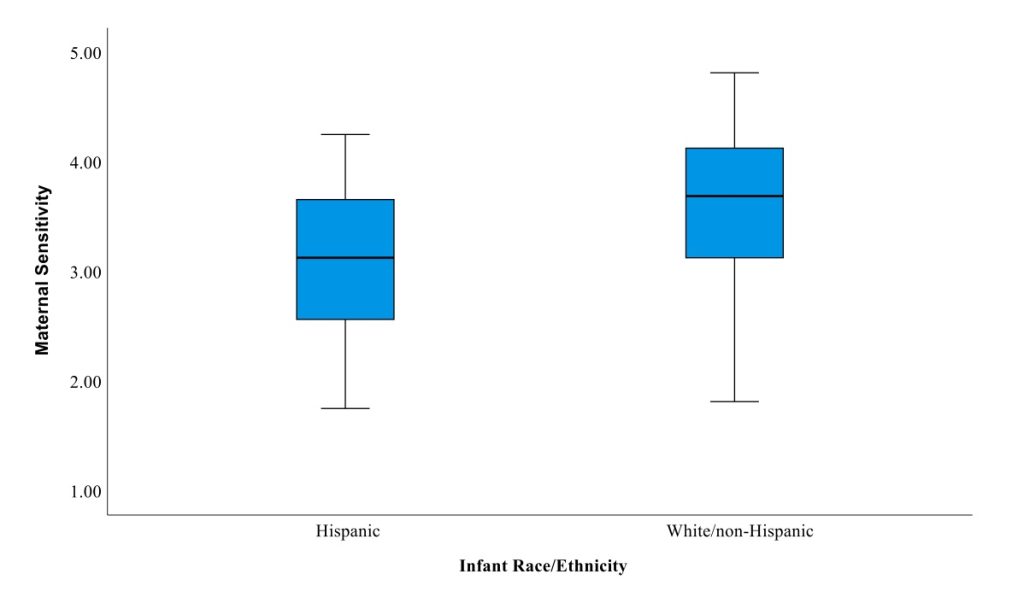

Question 2: Maternal sensitivity during free-play interaction

– A one-way ANOVA revealed that mothers of White/Non-Hispanic infants were significantly more sensitive than mothers of Hispanic infants (p = 0.003).

– See Graph 2: Question 2 Results.

Question 3: Association between sensitivity and infant distress

– Maternal sensitivity during free-play interaction was not significantly associated with infant distress during the Still-Face Paradigm for White/Non-Hispanic or Hispanic infants.

Conclusions

1. Hispanic and White/Non-Hispanic infants did not behave differently when distressed.

2. Hispanic and White/Non-Hispanic infants did experience different levels of maternal sensitivity. Further research is needed to understand the reasons for this difference.

3. The level of maternal sensitivity did not predict infant behavior while distressed, regardless of the infant’s race/ethnicity. Further research using measures of maternal sensitivity during the Still-Face Paradigm episodes instead of free-play session would be useful.

Graph 1: Question 1 Results

Graph 2: Question 2 Results

References

Conradt, E. & Ablow, J. (2010). Infant physiological response to the still-face paradigm: Contributions of maternal sensitivity and infants’ early regulatory behavior. Infant Behavior and Development, 33, 251-265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.01.001

Harris, E. (2022). U.S. Census Bureau estimates for race and Hispanic origin, Vintage 2021. Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute, The University of Utah.

Huang, K., Caughy, M. O., Genevro, J. L. & Miller, T. L. (2005). Maternal knowledge of child development and quality of parenting among White, African-American, and Hispanic mothers. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 26, 149-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2004.12.001

Huang, Z. J., Lewin, A., Mitchell, S. J. & Zhang, J. (2012). Variations in the relationship between maternal depression, maternal sensitivity, and child attachment by race/ethnicity and nativity: Findings from a nationally representative cohort study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16, 40-50.

Li, W., Woudstra, M., Branger, M., Wang, L., Alink, L., Mesman, J., & Emmen, R. (2019). The effect of the still-face paradigm on infant behavior: A cross-cultural comparison between mothers and fathers. Infancy, 24, 893-910. DOI: 10.1111/infa.12313

Lowe, J. R., Coulombe, P., Moss, N. C., Rieger, R. E., Aragon, C., MacLean, P. C., Caprihan, A., Phillips, J. P. & Handal, A. J. (2016). Maternal touch and infant affect in the Still Face Paradigm: A cross-cultural examination. Infant Behavior and Development, 44, 110-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2016.06.009

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (1996). Characteristics of infant child care: Factors contributing to positive caregiving. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 11, 269–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2006(96)90009-5

Mesman, J., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2009). The many faces of the Still-Face Paradigm: A review and meta-analysis. Developmental Review, 29, 120-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2009.02.001

Shin, H., Park, Y., Ryu, H., & Seomun, G. (2008). Maternal sensitivity: a concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 64, 304-314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04814.x