2 Frederick Taylor

Scientific Management, Taylorism, Time and motion studies

Resa Wise; Rick Hardcopf; and Mike Dixon

Frederick Taylor (1856 – 1915)

Scientific Management, Taylorism, Time and motion studies

Nineteenth century America can be described as a period of growth. Land mass grew via the Louisiana purchase, population grew through immigration, civil rights gained momentum after the Civil War, and the economy grew through industrialization [1]. Factories became popular, especially in the northern states and Frederick Taylor was a pioneer in facilitating the growth of that industrialization.

Taylor was born March 20, 1856 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy and graduated at the top of his class. Although he was accepted to Harvard, he did not attend for medical reasons. In 1883 he earned a mechanical engineering degree and started his career as an apprentice patternmaker and machinist at Enterprise Hydraulic Works. He subsequently worked for the Midvale Steel Company, in many positions, including machine shop laborer, shop clerk, foreman, engineer, and manager. In 1890 he left Midvale to work for the Manufacturing Investment Company and eventually he became a consulting engineer in management [2].

By the end of his life, Taylor had become very accomplished. He held over forty patents, was elected President of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, earned an honorary Doctor of Science from the University of Pennsylvania, and published a paper titled The Art of Cutting Steel, which featured over 30,000 experiments from his time at Midvale [2], [3]. Through his work experience, Taylor became very interested in perfecting the manufacturing process, and he took a very scientific approach to increase productivity. His ideas are known as Scientific Management, or Taylorism. In 1911 he published his ideas in the book, the Principles of Scientific Management.

Scientific Management

During his time at Midvale, Taylor noticed the workers were not always efficient, costing the company money. This led him to begin conducting time studies to find the one most efficient way to complete any activity. Taylor believed in the division of labor idea popularized by Adam Smith, i.e., every employee should be given one task to complete and become experts at. He took the idea a step further and purported that all parts of a job could be scientifically studied to identify the proper equipment and process steps to complete a task. After watching laborers work, he documented their movements and created scientific experiments, on the shop floor, to determine the optimal manner to do very specific subtasks.

“In the past the man has been first; in the future the system must be first.”

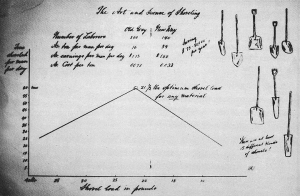

In 1898, he conducted one of his most famous experiments for Bethlehem Steel to improve the efficiency of 600 shovelers at their plant. He set off to find the size of shovel and manner to work that would optimize the employees’ efforts. Using a stopwatch, he measured the time it took for hired men to move dirt from a pile. The next day, he trimmed the size of the shovel and again record the time the men moving the pile. He repeated this with different sizes of shovels until he found the shovel size the completed the job fastest. He reported that with the optimal size shovel (21.5 lbs) output per shoveler doubled. Any shovel heavier or lighter would reduce the output of the employees.

“ For a first-class shoveler there is a given shovel load at which he will do his biggest day’s work. What is this shovel load? Will a first-class man do more work per day with a shovel load of 5 pounds, 10 pounds, 15 pounds, 20, 25, 30, or 40 pounds?”

Taylor believed there was a single best way to complete any task [4] and that the one best way should be standardized into the processes and culture of a company. He taught that in many fields the “rule of thumb” about how a task should be completed is often far from optimal. Taylor described that managers rely heavily on “gut feelings” and personal preference rather than data [5], but that in order to increase productivity they should standardize every process, cost, and tool based on a systematic and scientific approach to management.

Impact on Employees

Taylor taught that in addition to process and tools, workers should be selected scientifically as well. With the most suitable person, the output of a give task should improve. He noted that, left unchecked, most workers will work at the slowest rate that will go unnoticed. He pointed out that workers don’t have interest in working harder or faster than is expected a principle he called “soldering” implying workers just go at the pace of those around them. Although often ignored by some of his disciples in what was later caller Taylorism, he suggested that highly productive employees should be rewarded for their work usually through a piece work pay scheme. In this way, employees will share from the companies benefit if they work better than those around them.

Taylorism, evolved into making clear distinctions between workers and managers forming a belief that workers should be responsible for carrying out the workload while managers should plan and supervise workers. While Taylor taught that managers needed to be experts who studied production and should exercise control over employees, much of his teaching about fairness and cooperation with employees was passed over by his contemporaries that carried the banner of Scientific Management into various industries.

Critics of Taylorism point out that the Scientific Management could lead to authoritarian leadership. Taylor wrote, “A high-priced man does what he’s told to do and no back talk . . .. When [the manager] tells you to walk, you walk; when he tells you to sit down, you sit down . . .,” [3]. The “one best way” approach to work meant work could become monotonous, and workers left with little dignity and lack of motivation to take individual initiative. This criticism came to a head when Harrington Emerson testified before the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United State purporting that the railroad industry could improve by one million dollars a day if Scientific Management principles were put into place. This brought national attention to Taylor’s ideas and ignited some labor disputes in several industries that claimed Taylorism efficiency gains depended solely on the backs of workers without any renumeration for their increased productivity.

Although Taylorism’s beliefs about worker rights and responsibilities were harsh, and outdated by today’s standards, they were effective. Taylorism is touted for doubling or even tripling some factories’ productivity in the first decades of the 1900s.

The Big Idea for Operations Management

We will see that many of his predecessors refined his ideas about employee treatment; however, modern operations still prioritize efficiency and productivity and Taylor’s ideas about labor specialization and stadardization heavily influenced Henry Ford and the development of the assembly line. Further, the fundamental idea that workers who specialize in a single task are more productive, at least in the short term, is an accepted truth. Many companies use this fact when designing operational systems and processes. The scientific method is also still heavily used to test out new ideas about how to improve and simplify processes and create systems that have consistent quality output.

Sources

[1] Oxford Reference, “Timeline: 19th century,” Oxford Reference, 2012. https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780191735622.timeline.0001;jsessionid=F53387F9E3A226975C8FE14D6E28E9EE (accessed Sep. 02, 2023).

[2] J. F. Mee, “Frederick W. Taylor – American inventor and engineer,” Britannica, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Frederick-W-Taylor (accessed Sep. 02, 2023).

[3] D. Hounshell, “The Same Old Principles in the New Manufacturing,” Harvard Business Review, 1988. https://hbr.org/1988/11/the-same-old-principles-in-the-new-manufacturing

[4] C. Strange, “The secret was in the shovel,” Cricket, vol. 19, no. 9, pp. 25–29, 1992.

[5] J. Gordon, “Scientific Management Theory – Explained,” The Business Professor, 2022. https://thebusinessprofessor.com/en_US/management-leadership-organizational-behavior/what-is-scientific-management-theory (accessed Sep. 02, 2023).