6 OER as Assessment; Assessment as OER: Collaborative OER Creation and Assessment in language and culture courses

Michael Tadeusz Dabrowski and Angela George

Abstract

This chapter describes the transformative integration of Open Educational Resources (OER) utilized as assessments in language courses at two distinguished Western Canadian universities. It explores how OER, underpinned by a commitment to collaborative learning and evaluation, reshape educational practices. Through collaborative maps, peer editing, and renewable assignments, educators and students collectively contribute to the creation of a repository of knowledge, embracing a pedagogical paradigm that values student engagement and deepens their understanding of OER. This process demonstrates the ability of OER to redefine academic assessment and collaboration, showcasing how OER can transform the educational experience into a more engaging, enriching, and equitable journey.

Keywords: OER-Enabled Pedagogy, OER Assessment, Mapped Learning, Student Authorship, OER Creation

Introduction

Open Education and Open Educational Resources (OER) have become increasingly recognized among educators over the past several years. Peter and Deimann (2013) trace the origins of open education back to the late Middle Ages when student-led demands for education, driven by learners’ growing curiosity and societal demand for widespread knowledge access, caused universities to emerge. By the 15th century educational control shifted from students to professors and centralized authorities. The 17th and 18th centuries saw the arrival of coffee houses and self-education societies that utilized peer-teaching as a gateway to open education. Finally, the arrival of the 19th and early 20th centuries meant the emergence of various institutions characterized by different degrees of openness (Peter & Deimann, 2013).

Weller et al. (2018) argue that the open education movement predates commonly recognized milestones such as the 2012 UNESCO declaration or Wiley’s (2014) emphasis on the 5Rs: reuse, revise, remix, redistribute, and retain. Their research extends the timeline of open education from the 1970s to the present, uncovering a multifaceted field marked by distinct, often isolated, sub-topics. Weller et al. (2018) note a tendency within open education research to focus introspectively, largely overlooking contributions and developments before the 1970s – a decade notable for the popularization of open pedagogy in the UK and the establishment of the Open University.

Historically, the success of open movements has often stemmed from student-led initiatives or efforts to meet students’ needs, suggesting that the student experience offers valuable insights into the societal impact of open educational pedagogy. Although the benefits of open pedagogy and OER for educators and institutions are well documented (Paskevicius, 2018), the student perspective remains underexplored. Engaging with students in open educational practices presents distinct challenges for instructors and institutions, and understanding these experiences is crucial for appreciating the full scope and potential of the open education movement.

This chapter will discuss the interplay among students as key players in open pedagogy and OER-based assessment strategies. These strategies were part of a series of language courses taught via in-person, hybrid, and online formats at two Western Canadian public universities. The activities discussed throughout this chapter remain fundamentally the same across delivery platforms; however, make allowances for differences due to synchronous or asynchronous instruction and assignments. Although our experience with OER as an assessment is limited to university Spanish courses, these examples can be extended to other disciplines. While we will rely mostly on the development of language skills and cultural awareness for our examples, we hope that the readers will be able to envision how these techniques could be applied in their specific academic sphere.

Collaborative Learning and Assessment

Traditionally, cultural activities within language courses have primarily depended on cultural content authored in textbooks, engaging students in a largely passive manner through reading or listening to materials. This approach typically culminates at examination time, where students’ retention and memorization skills are evaluated to determine how effectively they have internalized the content. While there have been opportunities for discussion and peer work to facilitate some degree of interaction, the fundamental premise has remained that all students are tasked with learning the same cultural content. This method positions the acquisition of cultural knowledge as a uniform experience, with individual learning paths converging on a standard set of culturally themed information deemed essential within the language learning framework. Over the decades, the cultural components of textbooks have remained relatively static while broadly taking advantage of the affordances provided by technology and media to enhance the delivery.

Dechert and Kastner (1989) investigated German language textbooks geared towards undergraduate students aiming to align the cultural topics in these first- and second-year German language textbooks with the interests of the students. The findings revealed that while there was general agreement on the importance of incorporating culture into language learning, the cultural topics of most interest to students were not always well represented in textbooks. With these findings in mind, we explored technologies and assessments that would allow students to be the drivers of content being studied rather than the textbook authors. In turn, this led us to the benefits offered through collaborative practices.

The term ‘collaborative learning’ can be misused, obscuring the practices and methodologies which it encompasses. Essentially, collaborative learning involves any learning activity where two or more individuals engage together, distinct from individual and cooperative learning. In this model, all participants contribute to and benefit from a shared pool of knowledge, enhancing their personal understanding through mutual exchange (Dillenbourg, 1999; McInnerney & Roberts, 2009; Ploetzner et al., 1999; Teasley & Roschelle, 1993; Vygotsky, 1978). Echoing the Socratic method, one member articulates their knowledge and catalyzes others to understand the material, prompting the original member to deepen their comprehension in a reciprocal teaching environment. This process assumes that all participants bring diverse skills and knowledge levels to the table, enriching the learning experience through shared insights, with learning transfer facilitated by conflict resolution techniques like argumentation (Littleton & Häkkinen, 1999). Such interdependence fosters accountability among students for individual contributions to collective knowledge creation (Teasley & Roschelle, 1993). While there is some ambiguity surrounding the details of collaborative learning, the consensus is that it involves multiple individuals leveraging each other’s input.

The integration of peer assessment into collaborative learning, especially in the context of rapid technological progress, has been extensively examined in recent research. This body of work, including studies by Altınay (2017), Alzaid (2017), Pantiwati and Husamah (2017), Ratminingsih et al. (2017), and the concept of “learning-oriented peer-assessment” introduced by Keppell et al. (2006), has underscored the significant advantages that self- and peer-assessment brings to collaborative learning environments. One of the recurring themes in this research is how technology facilitates the implementation of anonymous peer assessment, enhancing the learning experience (Ashenafi, 2017; Li, 2016) and spotlighting the utility of peer assessment in distance learning scenarios (Davies, 2000; Tenório et al.,2016). Furthermore, considerable attention has been given to the role of peer assessment in Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), with studies by Boudria et al. (2018), Meek et al. (2017), and Suen (2014) illustrating how these collaborative online environments support a continuous feedback loop on student assignments, even in the absence of constant instructor presence. Yet, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding applying these peer assessment practices within OER-enabled pedagogical frameworks, suggesting an area ripe for future exploration. Ironically, OER-enabled pedagogy fully permits a wide array of collaborative activities, which are often stifled by adherence to copyright laws.

Even in collaborative environments, the majority of assignments and assessments have been and continue to be disposable assignments, a term coined and argued against by Wiley (2013). However, many open educators are working to develop renewable assignments (Jhangiani, 2016; Seraphin et al., 2018; Wiley, 2016) to counter what Wiley defined as “assignments that add no value to the world – after a student spends three hours creating it, a teacher spends 30 minutes grading it, and then the student throws it away. Not only do these assignments add no value to the world, they actually suck value out of the world” (n.p.) Renewable assignments are the cornerstone of his expanded 5Rs (Retain, Revise, Remix, Reuse, Redistribute) OER-enabled pedagogy and are designed to benefit the learning commons through harnessing the intellectual efforts of students. This approach values student work as a continuing resource that can enrich the educational community, rather than just a learning exercise for the individual. Through this strategy, the efforts put into assignments and assessments are transformed into OER, further extending the reach and impact of educational materials to the learning commons. Wiley (2016) optimistically states: “Over time, we could see a transition to a place where the majority of content and assessments a learner encounters were created “by students, for students” with editorial support from faculty (i.e., “grading”) (n.p.).

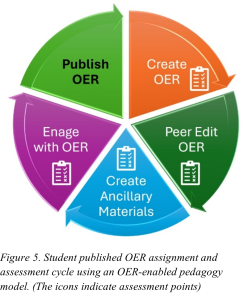

OER-enabled pedagogy facilitates the repurposing of OER created into learning assessment methods. At the same time, peer- and instructor-led assessments of OER elements fulfill an editorial role in developing OER. Assessing (grading) and editing becomes synonymous, and this work is leveraged to produce higher-quality resources for future learners.

Embracing the cyclical nature of Hilton III et al.’s (2010) original 4Rs [Reuse, Redistribute, Revise, Remix] and Wiley’s (2014) expanded 5R model, Athabasca University and the University of Calgary have incorporated collaborative OER Creation and Assessment into multiple courses through collaborative map assignments and multiple peer-editing activities. These assignments then become OER for future use.

Collaborative Maps

In educational settings, globes and maps have long served as indispensable tools, bridging the gap between theoretical learning and geographical reality (Bartz, 1970). These resources enable students to visualize our planet’s vast and varied terrains, thus enhancing their understanding of different regions, cultures, and the intricacies of global geography. Indigenous Peoples’ connection to land and place goes beyond mere physical space; it encompasses a deep-seated cultural, spiritual, and historical significance (First Nations Education Steering Committee, 2015). By integrating globes and maps into the learning process, educators facilitate a better comprehension of geographical concepts while also respecting and acknowledging the profound bond between Indigenous communities and their ancestral lands. This approach to learning emphasizes the importance of place in the cultivation of knowledge, ensuring that students gain a more holistic and respectful awareness of the world’s diversity and the unique perspectives of its inhabitants.

With the advent of digital technologies, interactive maps can serve as an instructional tool in various ways at the postsecondary level, enabling students to direct their own learning while maintaining this link to geography (Matias et al, 2013, p. 231). Matias et al. (2013) discuss and advocate for the use of static content in educational resources, which is when students are limited to viewing the map without the ability to edit or contribute to it. This approach recreates the traditional textbook model and only utilizes map technology advances to deliver pedagogical content more interactively. Free and Ingram (2018) provide ideas for how maps can be implemented in the future student-created content in their French theatre course.

Google Maps,  with its capability to geolocate information and allow for multiple editors, provides versatility across various educational contexts. This technology is a powerful tool for creating and sharing cultural, historical, political, and personal points of interest. By enabling this level of interaction and content creation, Google Maps facilitates a unique educational experience where knowledge and insights have the potential to reach a global audience rather than being confined to individual classes or cohorts. Allowing students to contribute to and benefit from interconnected information across different disciplines broadens educational impact and enriches learning experiences beyond what traditional map-based educational resources could provide.

with its capability to geolocate information and allow for multiple editors, provides versatility across various educational contexts. This technology is a powerful tool for creating and sharing cultural, historical, political, and personal points of interest. By enabling this level of interaction and content creation, Google Maps facilitates a unique educational experience where knowledge and insights have the potential to reach a global audience rather than being confined to individual classes or cohorts. Allowing students to contribute to and benefit from interconnected information across different disciplines broadens educational impact and enriches learning experiences beyond what traditional map-based educational resources could provide.

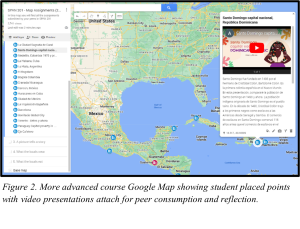

This activity enables large student groups to collaboratively build a map, where they can add points accompanied by text and multimedia descriptions that appear when these points are hovered over. The activity’s complexity can be tailored to match the course’s themes and the students’ proficiency levels. For beginners, the focus is on researching cultural elements and synthesizing information into English for others. At a more advanced level, students create presentations like those given in a traditional class, which their peers can view asynchronously. Initially, this task merges cultural research with developing writing and speaking skills in the target language. Students then listen to these presentations for summarization, gaining additional cultural insights. This listening component enhances their comprehension skills. Finally, writing a response re-engages them in the writing process, completing the skills development cycle.

Instructors initiate the process by setting up  a shared Google Map which includes a sample entry. Once this is created, the students are invited as editors to augment the map with additional points. Leveraging the contributions made by their peers—which now serve as an OER—students engage in a reflective exercise that forms a critical component of the assignment. This approach fosters collaborative learning and encourages students to critically engage with the content through the lens of their peers’ perspectives, enriching their educational experience.

a shared Google Map which includes a sample entry. Once this is created, the students are invited as editors to augment the map with additional points. Leveraging the contributions made by their peers—which now serve as an OER—students engage in a reflective exercise that forms a critical component of the assignment. This approach fosters collaborative learning and encourages students to critically engage with the content through the lens of their peers’ perspectives, enriching their educational experience.

By evolving the traditional educational approach from a singular, textbook-led pedagogical model to a more interactive and engaging dialogue among students, using maps as the central element of discussion, students are empowered to harness the value of peer work. This methodology transforms peer work into an OER, shifting towards a collaborative learning environment that fosters deeper academic engagement and cultivates essential interpersonal skills among students. Drawing upon the research conducted by scholars in intercultural competence, the NCSSFL-ACTFL (2017) speaks about the importance of integrating a structured framework that emphasizes reflective activities. Such a framework is designed to extend learning beyond the confines of the classroom, encouraging students to embark on profound reflective exercises in either the target language or a mutually understood common language. These activities aim to provide students with a more nuanced understanding of the content through in-depth reflections, thereby fostering a more holistic and enriched educational experience.

in intercultural competence, the NCSSFL-ACTFL (2017) speaks about the importance of integrating a structured framework that emphasizes reflective activities. Such a framework is designed to extend learning beyond the confines of the classroom, encouraging students to embark on profound reflective exercises in either the target language or a mutually understood common language. These activities aim to provide students with a more nuanced understanding of the content through in-depth reflections, thereby fostering a more holistic and enriched educational experience.

This map-based assignment can be extended with González-Lloret’s (2020) Google Earth task by allowing students to delve deeper into the cultural aspect of the assignment, even at the beginning level. In her “Planning a Tour of the City Task”, novice learners play a guessing game with landmarks they identify, intermediate learners collaboratively select a few important landmarks to describe to the class, and advanced learners prepare a tour of a city (González-Lloret, 2020, p. 266). All these activities allow learners to take individual journeys into the OER content created by their peers while providing the possibility for in-class activities driven by learner interest.

Under a conventional educational framework, such assignments would typically provide a singular opportunity for assessment that focuses on the individual cultural research of each student. However, transforming these outputs into OER opens avenues for multiple assessment opportunities. Beyond merely evaluating initial activities, this approach incorporates peer-review critique or editing as an additional, secondary form of assessment. Depending on the comfort level of the instructor and class, a reflective exercise can serve as a third layer of evaluation, allowing students to reflect on their own work and peer feedback. This multifaceted assessment strategy diversifies the evaluation process and enriches the learning experience by encouraging more profound engagement with material through various perspectives and critical feedback mechanisms.

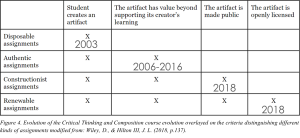

Collaborative Publishing

Collaborative publishing is used in university textual analysis and composition courses using the same resource materials. When taught for the first time in 2003, the course followed the structure previously established by department colleagues, emphasizing individual assignments. This traditional approach involved students completing assignments independently and submitting them to the instructor for evaluation and feedback, using the textbook as a guide for various writing styles, exemplars, and activities. Aiming to foster greater involvement in the writing and editing phases, the course was revamped in 2006 to incorporate group work. This change aimed to enhance course outcomes by enabling students to share, read, and provide feedback on each other’s drafts. It soon became apparent that for this collaborative approach to be practical, students needed to pre-read drafts prior to class so that in-class discussions were productive. As the course evolved, its structure was adjusted to include in-class collaborative editing under instructor guidance alongside in-class group discussions about at-home revisions. However, this pedagogical approach took a significant turn after encountering the works of Wiley (2016) leading to an exploration of the potential of open pedagogy. In 2018, OER were integrated into the course, marking the transition to an OER-enabled pedagogical model. The framework of Wiley and Hilton III’s (2018) which highlights the shift from disposable to renewable assignments was adapted to chart the transformative journey of assignment design within this course over the years, highlighting the pedagogical evolution from traditional to open practices.

Due to copyright issues, the textbook used for 15 years could not provide the flexibility that open pedagogy promised and so began the transition in 2018 from the previous textbook to OER-enabled pedagogy. The course syllabus no longer specified a textbook. Instead, it outlined a table of contents for chapters to be authored by the students and a series of activities to be completed. A foundational OER was developed within two-course iterations, serving as the new textbook. Over time, students refined and expanded the textbook and its associated activities, culminating in a formal publication of the OER in 2023.

Embracing the fourth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 4), which emphasizes quality education for all, this course integrates learning about open education, the open commons, and OER creation with OER-enabled pedagogy at the heart of all aspects of learning. To provide the maximum thematic flexibility to students, the Sustainable Development Goals became the chapter topics and the thematic arc of the course. In addition to a few non-renewable assignments like personal presentations and short written texts, students created case studies of NGOs that addressed Sustainable Development Goal objectives in Latin American communities alongside original short stories loosely tied to the SDGs. Since these assignments were peer-edited, and some were later integrated into the OER, they provided an initial point of assessment during the creation process.

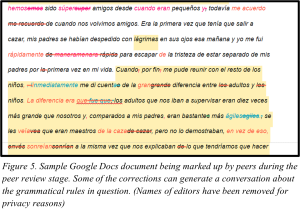

Students begin the process by composing their draft of the assignment. These initial submissions were informally reviewed by the instructor to ensure they were relevant and then students were provided direction for the content or structure. The reworked assignments were shared with the entire class, opening the door for a peer review phase. During this phase, classmates engaged in detailed examination of each other’s work, focusing on identifying and correcting grammatical errors and offering constructive feedback on strengthening the text’s structure and coherence. This interactive and collaborative approach to assessment encouraged students to take an active role in the learning process. By participating in giving and receiving feedback, students developed a stronger sense of accountability for their educational journey. This heightened sense of responsibility often increased motivation and effort as students aimed to improve their work and contribute to their peers’ learning and development. More importantly, this peer review process was integral to the assessment of the students’ work, both the substance of the initial assignment and the quality and helpfulness of the peer feedback. Emphasis was placed on peers providing clear explanations for grammatical corrections and structural suggestions. This requirement ensured that the review process was educational and constructive rather than critical.

The collaborative nature of this assessment strategy  played a significant role in fostering a sense of community within the classroom. Students were encouraged to view learning as a shared endeavour through which they could work together towards common educational goals. This communal approach not only enhanced the learning experience for each individual student but also built a supportive and engaging classroom environment where students felt connected and invested in each other’s success. In this way, the assessment process was experienced as a collaborative learning opportunity.

played a significant role in fostering a sense of community within the classroom. Students were encouraged to view learning as a shared endeavour through which they could work together towards common educational goals. This communal approach not only enhanced the learning experience for each individual student but also built a supportive and engaging classroom environment where students felt connected and invested in each other’s success. In this way, the assessment process was experienced as a collaborative learning opportunity.

Following the peer review, authors integrated the suggested revisions into their work, culminating in submitting a polished final version for assessment. Unlike disposable assignments, which tend to be linear with the objective of submitting something for evaluation, this revision process promoted a cyclical approach to writing and research that focused on the quality of final outputs for public consumption. While an unanticipated benefit when first utilized, this iterative strategy limited the use of generative AI, or at the very least encouraged teachers and students to use technology intelligently to benefit their creative processes.

Since some of these texts will be added as primary OER reading materials for future course iterations, they also provided multiple possibilities for derivative assessments. After students read a text, they were required to create content questions to demonstrate their understanding of the text, discussion topic questions that expanded on themes in the texts to generate classroom conversation, and vocabulary lists that became part of an integrated glossary to help students navigate complete texts without using online tools or dictionaries. Each derivative assignment was assessed and, if appropriate, was added to the OER, completing the activities, and reading supports complementing each text. The questions and discussion topics were then utilized as a tertiary level of assessment for students to demonstrate their understanding of the text by responding to the questions and discussions either in written format or verbally in class.

Written assignments go through  iterative editing processes involving peers’ work as a form of assessment for the creator and the editor, thus allowing the same OER text to provide an assessment point for multiple students. These open assessments are dialogic and create an environment where students can support each other’s learning, sharing insights and resources. This approach provides learning opportunities for everyone involved and future students who utilize the material.

iterative editing processes involving peers’ work as a form of assessment for the creator and the editor, thus allowing the same OER text to provide an assessment point for multiple students. These open assessments are dialogic and create an environment where students can support each other’s learning, sharing insights and resources. This approach provides learning opportunities for everyone involved and future students who utilize the material.

As mentioned, post-text work involves collaboratively creating supporting questions, discussion topics and a list of difficult words with translations. Students working in a shared document create these supporting materials, review them, make changes, and finalize them as part of their collaboration assessment. Each major assignment has one or more collaboration objectives that have to be met in order to receive evaluation by the instructor. The reflective practice of highlighting vocabulary that poses a personal problem enhances the acquisition of new words, provides an assessment point, and provides a peer-generated list of “challenging” words. This overcomes the often-impossible task for educators, with decades of teaching experience and likely native or native-like language fluency, to identify words that are challenging to students at a particular level of competence. The collaborative vocabulary list provides what the peers need, rather than conforming to lists made by instructors or ones that are found in textbooks.

Like all OER, this material benefits from the ongoing opportunity for iterative enhancement, allowing students to continuously refine and polish the texts. Unlike a static textbook, any improvements can be directly incorporated into the OER, enabling a constant capability for copy-editing and updating.

Knowing that peers will review their work motivates students to consider their audience more carefully. Targeting their writing at their skill level potentially improves the clarity and impact of their writing on peers. Additionally, if the course’s thematic content allows, the students can learn different writing styles, vocabulary, research methodologies, and ways of thinking by reviewing the work of their colleagues.

Conclusions

By discussing the various assessments used in our courses, we hope to have demonstrated some of the benefits of using OER as part of an assessment strategy. OER offer several benefits to assessment practices in education, enabling approaches and methodologies that are often challenging or impossible to implement with traditional assessment formats. Beyond traditional assessment strategies, like essays, quizzes, exams and presentations, OER-enabled assessments include interactive, synchronous, asynchronous, peer, and project-based activities that utilize, manipulate, and create open resources. This flexibility can help to accommodate different learning styles and abilities.

Teachers and educators can co-create or adapt existing OER assessments, fostering a culture of sharing and collaboration across institutions and borders. At the same time, students can contribute to or co-create OER as part of their learning process, encouraging engagement and a deeper understanding of the subject matter. One significant benefit of integrating OER into the assessment process is that students can utilize it within a personal portfolio, showcasing their skills and knowledge in a format that has real value for future educational purposes.

This investigation into the integration of OER for assessment purposes in language courses at two universities in Western Canada underscores a strong commitment to collaborative learning and evaluation. Emphasizing active peer participation and the innovative application of renewable assignments, this strategy nurtures an educational setting that is not only sustainable but also deeply rooted in open pedagogy principles. Furthermore, by adopting and contributing to OER, educational institutions can markedly decrease the expenses related to developing, licensing, and distributing educational content. This approach enhances the learning experience and represents a cost-effective solution for educational materials.

The transition towards OER-based assessment strategies demonstrates the versatility of using these resources and how they foster a participatory and inclusive educational setting. Through the strategic implementation of collaborative maps, peer editing, and the use of renewable assignments, in keeping with Wiley’s (2016) call to action, we can harness the collective intellectual efforts of students toward creating a repository of knowledge that benefits the broader learning community.

The discussion about the potential of OER to limit the reliance on generative AI in assignments and encourage the intelligent use of technology underscores a critical aspect of contemporary education. By advocating for an iterative approach to writing and research, educators are equipping students with the skills necessary to navigate the digital landscape judiciously. Through this, students are better equipped to utilize technology to enhance their creative and analytical capabilities rather than relying on it as a crutch. This strategic alignment with technological advancements ensures that the educational experience remains relevant and responsive to the evolving needs of the digital age.

Through the continued exploration and expansion of OER-enabled pedagogies, educators and students alike can contribute to a dynamic and evolving educational landscape that not only meets learners’ immediate needs but also anticipates future challenges and opportunities. The journey into OER-enabled pedagogy detailed in this chapter is a testament to the transformative power of OER in redefining the parameters of academic assessment and collaboration. By embracing the full spectrum of opportunities presented by OER-enabled pedagogy, from creating renewable assignments to fostering a collaborative classroom environment, educators can pave the way for a more engaging and enriching educational experience in which assessment is genuinely integrated with the learning process.

References

Altınay, Z. (2017). Evaluating peer learning and assessment in online collaborative learning environments. Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(3), 312–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2016.1232752

Alzaid, J. M. (2017). The Effect of Peer Assessment on the Evaluation Process of Students. International Education Studies, 10(6), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v10n6p159

Ashenafi, M. M. (2017). Peer-assessment in higher education—Twenty-first century practices, challenges and the way forward. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(2), 226–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1100711

Bartz, B. S. (1970). Maps in the classroom. Journal of Geography, 69(1), 18-24.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00221347008981738

Boudria, A., Lafifi, Y., & Bordjiba, Y. (2020). Collaborative Calibrated Peer Assessment in Massive Open Online Courses. In I. Management Association (Ed.), Learning and Performance Assessment: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications (pp. 1408-1434). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-0420-8.ch065

Davies, P. (2000). Computerized Peer Assessment. Innovations in Education & Training International, 37(4), 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/135580000750052955

Dechert, C., & Kastner, P. (1989). Undergraduate Student Interests and the Cultural Content of Textbooks for German. The Modern Language Journal, 73(2), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.2307/326573

Dillenbourg, P. (1999). What do you mean by collaborative learning? In P. Dillenbourg (Ed.), Collaborative Learning: Cognitive and Computational Approaches (pp. 1–19). Oxford: Elsevier.

First Nations Education Steering Committee. (2015). First Peoples Principles of Learning [Poster], Retrieved from http://www.fnesc.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/PUB-LFP-POSTER-Principles-of-Learning-First-Peoples-poster-llxl7.pdf

Free, R., & Ingram, M. (2018). Collaborative Mapping to Enhance Local Engagement and Interdisciplinary Dialogue in a Short-term Study Abroad Program. International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing, 12(1), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.3366/ijhac.2018.0202

González‐Lloret, M. (2020). Collaborative tasks for online language teaching. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 260-269. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12466

Hilton III, J. L., Wiley, D., Stein, J., & Johnson, A. (2010). “The four R’s of openness and ALMS Analysis: Frameworks for Open Educational Resources.” Open Learning: The Journal of Open and Distance Learning, 25(1), 37-44, https://doi.org/10.1080/02680510903482132

Jhangiani, R. (2016). Ditching the “Disposable assignment” in favor of open pedagogy [Preprint]. Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/g4kfx

Keppell, M., Au, E., Ma, A., & Chan, C. (2006). Peer learning and learning-oriented assessment in technology-enhanced environments. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(4), 453-464. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930600679159

Li, L. (2016). The role of anonymity in peer assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(4), 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1174766

Littleton, K., & Häkkinen, P. (1999). Learning Together: Understanding the Process of Computer-Based Collaborative Learning. In P. Dillenbourg (Ed.), Collaborative Learning: Cognitive and Computational Approaches (pp. 20–30). Oxford: Elsevier.

Matias, A., Aird, S. M., & Wolf, D. F. (2013). Innovative teaching methods for using multimedia maps to engage students at a distance. In L. A. Wankel & P. Blessinger (Eds.), Increasing Student Engagement and Retention using Multimedia Technologies: Video Annotation, Multimedia Applications, Videoconferencing and Transmedia Storytelling (pp. 215-234). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2044-9968(2013)000006F011

McInnerney, J. M. & Roberts, T. S. (2009). Collaborative and Cooperative Learning. In P. Rogers, G. Berg, J. Boettcher, C. Howard, L. Justice, & K. Schenk (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, Second Edition (pp. 319-326). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-198-8.ch046

Meek, S. E. M., Blakemore, L., & Marks, L. (2017). Is peer review an appropriate form of assessment in a MOOC? Student participation and performance in formative peer review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(6), 1000–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1221052

NCSSFL-ACTFL. (2017). Reflection: Intercultural communication. https://www.actfl.org/sites/default/files/can-dos/Intercultural%20Can-Dos_Reflections%20Scenarios.pdf

Pantiwati, Y., & Husamah (2017). Self and Peer Assessments in Active Learning Model to Increase Metacognitive Awareness and Cognitive Abilities. International Journal of Instruction, 10(4), 185-202. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2017.10411a

Paskevicius, M. (2018). Exploring educators experiences implementing open educational practices (Thesis, University of Victoria). https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/CA77BB

Peter, S., & Deimann, M. (2013). On the role of openness in education: A historical reconstruction. Open Praxis, 5(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.5.1.23

Ploetzner, R., Dillenbourg, P., Preier, M., & Traum, D. (1999). Learning by Explaining to Oneself and to Others. In P. Dillenbourg (Ed.), Collaborative Learning: Cognitive and Computational Approaches (pp. 103–121). Oxford: Elsevier.

Ratminingsih, N. M., Artini, L. P., & Padmadewi, N. N. (2017). Incorporating Self and Peer Assessment in Reflective Teaching Practices. International Journal of Instruction, 10(4), 165-184. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2017.10410a

Seraphin, S. B., Grizzell, J. A., Kerr-German, A., Perkins, M. A., Grzanka, P. R., & Hardin, E. E. (2018). A Conceptual Framework for Non-Disposable Assignments: Inspiring Implementation, Innovation, and Research. Psychology Learning & Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725718811711

Suen, H. K. (2014). Peer assessment for massive open online courses (MOOCs). The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(3). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i3.1680

Teasley, S. D., & Roschelle, J. (1993). Constructing a joint problem space: The computer as a tool for sharing knowledge. In S. P. Lajoie & S. J. Derry (Eds.), Computers as Cognitive Tools (pp. 229–257). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Tenório, T., Ibert Bittencourt, I., Isotani, S., & Silva, A. P. (2016). Does peer assessment in on-line learning environments work? A systematic review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.020

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Weller, M., Jordan, K., DeVries, I., & Rolfe, V. (2018). Mapping the open education landscape: Citation network analysis of historical open and distance education research. Open Praxis, 10(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.2.822

Wiley, D. (2013). What is Open Pedagogy? Iterating toward Openness. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975

Wiley, D. (2014) “The Access Compromise and the 5th R” – Iterating Toward Openess https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/3221

Wiley, D. (2016). Toward Renewable Assessments. Iterating toward Openness. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/4691

Wiley, D., & Hilton III, J. L. (2018). Defining OER-Enabled Pedagogy. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(4). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i4.3601

Media Attributions

- google maps

- google maps 2

- google maps 3

- google maps 4

- google maps 5

- google maps 6