7 Confidentiality and Security

Laura K. Garner-Jones

Chapter 7 Overview

- History of privacy and security legislation

- Confidentiality practices for nurses

- Security and data privacy: Healthcare organizations

- Security and data privacy: Patients

Introduction

Protecting patient information is both a legal obligation and a core ethical duty for all healthcare providers, including nurses. Patients place their trust in us, and part of honoring that trust means safeguarding their personal health information (PHI). When individuals fear their private information might be mishandled or shared inappropriately, they may withhold important details or avoid care altogether, putting their safety and outcomes at risk (Carter-Templeton et al., 2025).

The American Nurses Association Code of Ethics (2024) affirms our responsibility to uphold patient rights, stating, “The nurse establishes a trusting relationship and advocates for the rights, health, and safety of recipient(s) of nursing care.” Similarly, the “Patient Bill of Rights and Responsibilities” details the expectation of confidential communication with healthcare providers (U.S. Department of State, n.d.). In addition, healthcare organizations must develop and communicate clear privacy practices through a “Notice of Privacy Practices.” The notice details the organization/provider’s duty to protect the patient’s privacy, the use and disclosure of their private health information (PHI), along with the patient’s rights regarding their medical records.

To ensure that patients’ privacy is protected and electronic health records are secure, federal legislation such as HIPAA and HITECH was enacted to set strict standards around the privacy and security of health information. Let’s take a closer look at what these laws require and how they directly impact nursing practice.

History of Privacy & Security Legislation

Because electronic health records (EHRs) are connected to the Internet, we must be concerned with protected health information (PHI) so that it is secure when used or shared with other healthcare providers. Two important pieces of legislation enacted to protect PHI include the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 and the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009. “It is important to be aware that the HITECH Act and HIPAA are separate and independent laws. However, because some provisions of HITECH strengthened existing HIPAA standards and mandated breach notifications, HITECH is often (incorrectly) regarded as part of HIPAA” (HIPAA Journal, 2023).

Definition: Protected health information (PHI) is defined as individually identifiable health information that is transmitted or maintained in any form or medium (electronic, oral, or paper) by a covered entity or its business associates, excluding certain educational and employment records (National Institutes of Health, 2007b).

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996

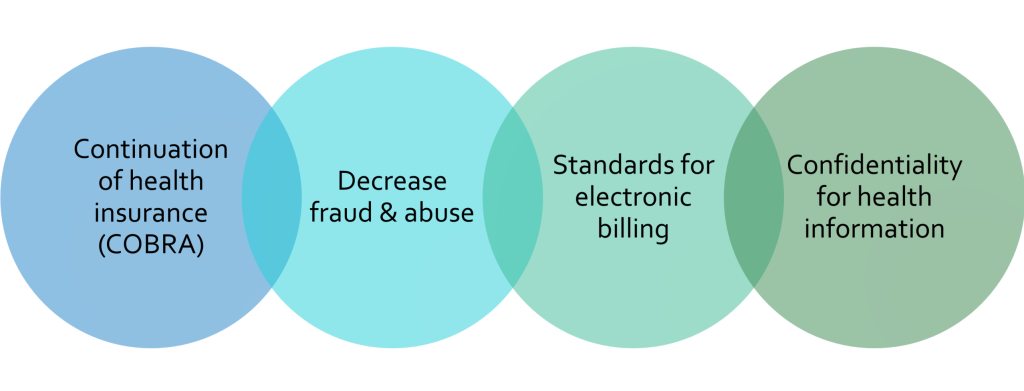

HIPAA is a federal law requiring the creation of national standards to protect sensitive patient health information from being disclosed without the patient’s consent or knowledge (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). HIPAA privacy and security rules grew out of two statutes in the 1970s that addressed the concerns for confidential patient information: first, the Comprehensive Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Act of 1970, and then the Drug Abuse Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Act of 1972 (Health & Human Services, 1994). Protecting the identities of people seeking treatment for addiction was a catalyst for our “current need to know” policies that define many of our information security strategies. According to HealthIT (2021), HIPAA was signed into law in 1996. In addition to privacy and security, HIPAA also includes the ability to continue health insurance when someone changes or loses their employment (COBRA). Further, HIPAA created standards for electronic healthcare transactions, measures to decrease fraud and abuse, including national identifiers for healthcare providers, insurers, and employers (See Graphic 7.1).

Graphic 7.1 – HIPAA Components

HIPAA Privacy and Security Standards

-

- HIPAA Privacy Rule: Establishes national standards to protect individuals’ medical records and other personal health information. It applies to health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, and healthcare providers that conduct certain healthcare transactions electronically. The rule applies safeguards to protect the privacy of personal health information and sets limits and conditions on the uses and disclosures of such information without patient authorization. The rule also gives patients rights over their own health information, including the right to examine and obtain a copy of their records and request corrections (Health Information Management Systems Society, 2021).

- HIPAA Security Rule: Sets national standards for protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronically protected health information. Compliance with the Security Rule was required as of April 20, 2005. The rule addresses the technical and non-technical safeguards that “covered entities” must have to secure an individual’s electronic health information. Before HIPAA, there were no generally accepted requirements or security standards for protecting health information (Health Information Management Systems Society, 2021).

Covered Entities

Protecting electronic patient information requires a definition of who is required to follow HIPAA privacy and security requirements. Under HIPAA, only a covered entity is required to be HIPAA-compliant and responsible for data breaches. Covered entities are defined in the HIPAA rules as:

-

- Health plans that provide or pay the cost of medical care,

- Health care clearinghouses, such as a billing system or health management information system, and

- Health care providers (National Institutes of Health, 2007a).

In general, a covered entity is any entity that provides, bills, or receives payments for healthcare services as part of its normal business activities. For example, if a clearinghouse processes or facilitates the processing of health information from nonstandard or standard formats into standard or nonstandard formats, this qualifies them as a covered entity. Private group healthcare benefit plans and insurers that provide or pay for the cost of medical care qualify these groups as a covered entity. An exception is that if the benefit plan has fewer than 50 participants and is self-administered, it is not a covered entity. Supplemental Medicare policies and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) are covered entities.

Considering these definitions, health insurance companies, HMOs, employer-sponsored health plans, Medicare, Medicaid, military, and veterans’ health programs are covered entities. Health Data Clearinghouses, doctors, clinics, psychologists, dentists, chiropractors, nursing homes, and pharmacies are covered entities.

Suppose a covered entity uses the services of a third party, such as a Cloud Service Provider. In that case, they must have a written Business Associates Agreement (BAA) contract that establishes what this third party has been engaged to do and identifies and controls the amount of access a vendor could have to protected health information (CMS, 2016). Some other examples are a third party that helps with health plan claims processing, utilization review consultants, and independent medical transcriptionist services for physicians (Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2021a).

Safeguards

Before HIPAA became law in 1996, there was no accepted standard for protecting health information. The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) outlined the policies and procedures needed to protect patient information. Security is one of the primary concerns organizations have in protecting patient health information (PHI), and sharing it with other organizations in health information exchanges. Three security safeguards are used to secure an organization’s protected health data: administrative, physical, and technical.

-

-

- Administrative safeguards demonstrate appropriate written policies, procedures, and job descriptions, including sanctions for violations, so staff are aware and can be properly trained.

-

- Physical safeguards define user access, training, disaster planning, backup, facility inventory, safeguards for unauthorized physical access or tampering, and contingency plans.

-

- Technical safeguards include unique user-identified password policies, user access allowed, automatic log-off, email policies, encryption, and data transmission protocols.

-

With the increased adoption of EHRs, there is an increased vulnerability to data breaches. HIPAA administrative, technical, and physical safeguards must be implemented to keep protected health information (PHI) confidential, private, and secure (HealthIT, 2017).

Threats

Inside the healthcare organization, security training for all staff accessing the information system is critical to protecting health information. The threats to information security can be intentional or unintentional. The threat source is either internal or external to the organization. Intentional exposure of patient information without authorization can result from a hacker or a disgruntled employee using malicious software – malware. Intentional destruction of data or network disruption can result from various forms of malware, including viruses, Trojan Horses, spyware, worms, Ransomware, and rootkits. Organizations must provide, at a minimum, annual security training so that the health information systems that staff are using are less likely to be compromised (Conn, 2016). In addition, the appropriate password complexity and security must be enforced for each user of the system. The security precautions to prevent an internal breach include not sharing passwords and not downloading information or unauthorized software from insecure or forbidden sites.

More information on HIPAA: Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

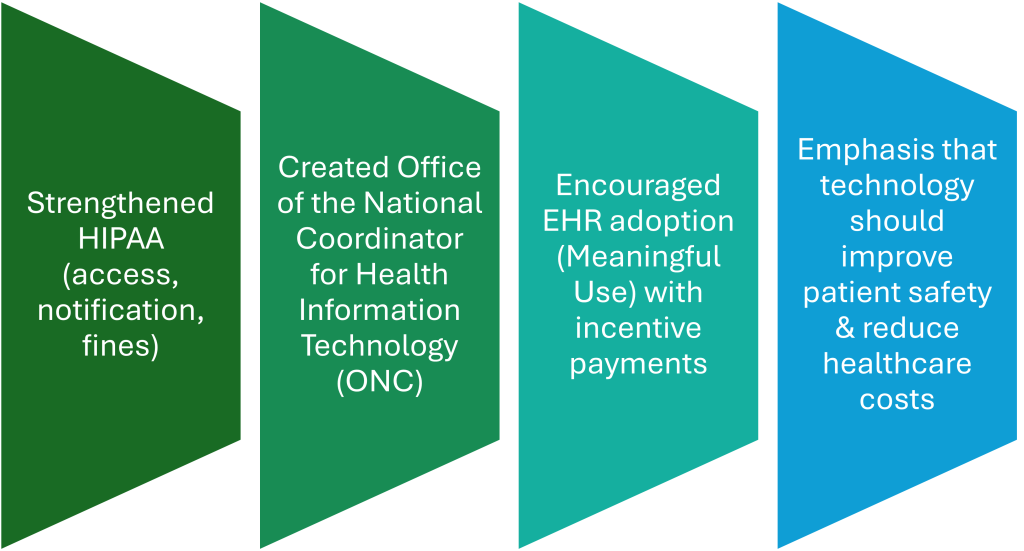

Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) of 2009

HITECH was part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), which provided the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) the authority to create programs that would improve quality, safety, and efficiency in the exchange of health information (USDHHS, 2017). HITECH expanded the adoption of Health IT, such as EHRs, by providing funding through incentive payments authorized by Medicare and Medicaid, among other things (See Graphic 7.2). Funding was provided to hospitals and clinicians who could demonstrate the “Meaningful Use” of EHRs by integrating clinical quality measures in patient care (USDHHS, 2017).

Graphic 7.2 – HITECH Components

Meaningful Use is defined as “the use of certified electronic health record by healthcare providers to improve the safety, efficiency, and quality of care. It includes the:

-

-

Use of certified EHR technology in a meaningful manner (e.g., e-prescribing).

-

Use of certified EHR technology in a manner that provides for the electronic exchange of health information to improve the quality of care.

-

Use of certified EHR technology to submit clinical quality measures (CQM) and other measures” (Henricks, 2011).

-

To be eligible for the incentive payments, organizations/participants had to demonstrate the “Meaningful Use” of the certified EHR to improve the quality of healthcare by achieving clinical quality measures to meet meaningful use objectives. The Meaningful Use Incentive Program included privacy and security requirements that PHI would be protected from unauthorized access and that the patients would have access to their medical information (HealthIT, 2015).

HITECH not only encouraged the adoption of Certified EHRs but also removed loopholes in HIPAA by making the language describing HIPAA Rules more robust (HealthIT, 2015; HIPAA Journal, 2023). For example:

- Prior to the HITECH Act of 2009, there was no enforcement of a written business associate agreement (BAA), and covered entities could avoid sanctions in the event of a breach of PHI by a Business Associate by claiming they did not know the Business Associate was not HIPAA-compliant. Since Business Associates could not be fined directly for HIPAA violations, many failed to meet the standards demanded by HIPAA and were placing millions of health records at risk (HIPAA Journal, 2023).

Promoting Interoperability

In April 2018, CMS renamed the Meaningful Use Incentive Program the Promoting Interoperability Program. The change moved the program’s focus beyond the requirements of Meaningful Use to the interoperability of EHRs to improve data collection and submission, and patient access to health information (HIPAA Journal, 2023). As mentioned in Chapter 6, Interoperability is defined as the ability of two or more systems to exchange health information and use the information once it is received (HealthIT, 2013).

EHR Interoperability enables better workflows and reduced ambiguity, and allows data transfer among EHR systems and healthcare stakeholders. Ultimately, an interoperable environment improves healthcare delivery by making the right data available at the right time to the right people.

Want to know more? Medicare Promoting Interoperability 2021.

Confidentiality Practices for Nurses

As a general rule, nurses should not disclose or access PHI unless there is a “need to know,” which primarily means that it is necessary for treatment, payment, or healthcare operations. There are some exceptions. PHI disclosures are permitted without the patient’s consent when:

-

- Required by law (examples: organ donation, court order, suspicious death that could be related to a crime, to inform law enforcement about a crime and/or the location of the victims and perpetrator).

- For the public good (examples: prevention or control of disease, injury, disability, abuse and neglect, reporting adverse events related to FDA-regulated products, work-related injuries, research).

- To prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to health or safety when such disclosure is made to someone they believe can prevent or lessen the threat (including the target of the threat). May also disclose to law enforcement if the information is needed to identify or apprehend an escapee or violent criminal.

(USDHHS, 2025).

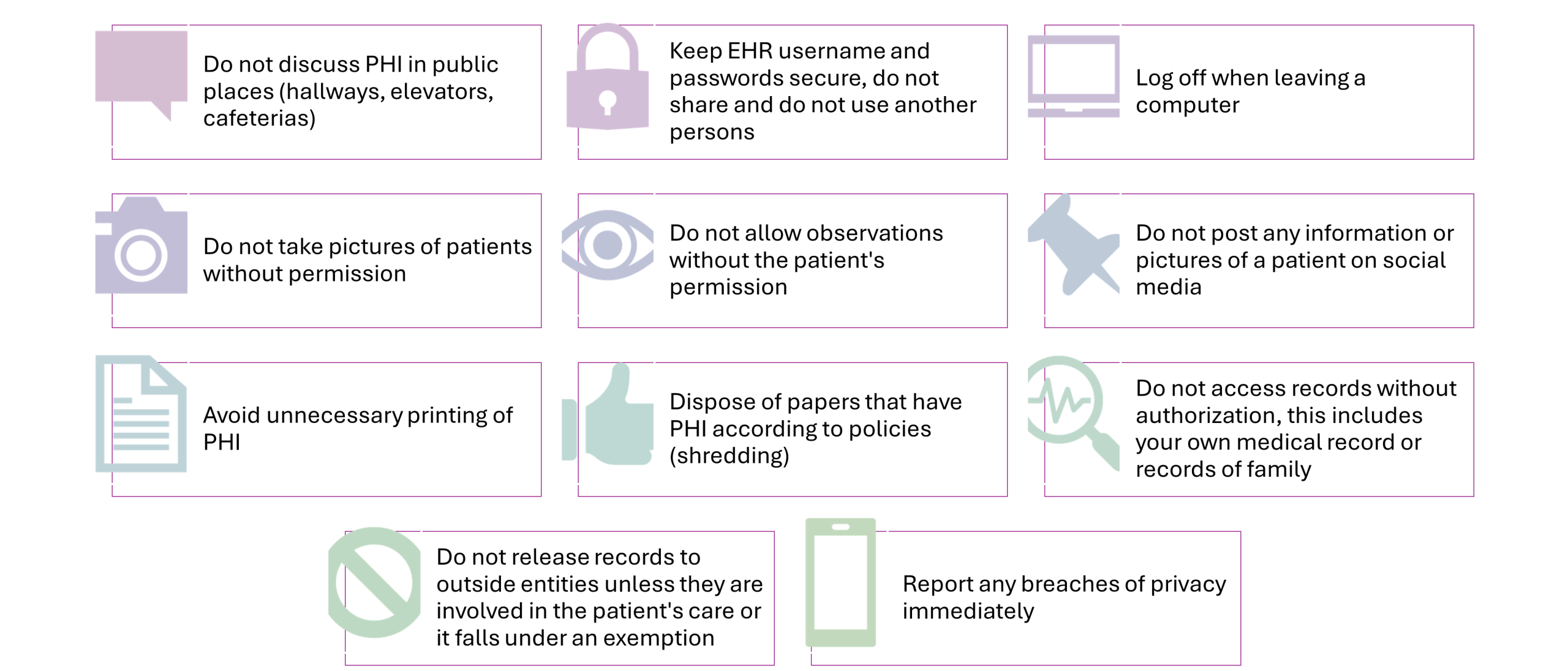

Practical Tips for Maintaining Confidentiality

Security and Data Privacy: Healthcare Organizations

Cybersecurity and data privacy are ongoing concerns as the adoption and use of innovative technologies increase. According to the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (2023), “Cybersecurity in healthcare involves the protection of electronic information and assets from unauthorized access, use, and disclosure. There are three goals of cybersecurity: Protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information, also known as the CIA triad.” Examples of technologies that healthcare organizations must protect include: EHR, including CDSS and CPOE, radiology information systems, smart infusion pumps, and remote patient monitoring devices (Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, 2023).

Want to know more? Visit: Cybersecurity in Healthcare and/or Improving the Cybersecurity Posture of Healthcare in 2022.

Security and Data Privacy: Patients

As healthcare becomes increasingly digital, patients are interacting with technology more than ever—whether through online support groups, patient portals, personal health records (PHRs), or telehealth services. These tools offer powerful ways to access care, manage health, and stay connected with providers. However, with these benefits come serious responsibilities and risks related to data privacy, security, and confidentiality.

Patients are often required to share personal health information online or through digital platforms—sometimes without fully understanding where that information goes, how it’s used, or who can access it. This section explores how patients can take an active role in safeguarding their health information. Nurses don’t just care for patients; part of our role is also providing education. Educating patients and families on privacy, security, and confidentiality will further validate why nursing is the most trusted profession.

In this section, we will examine privacy concerns and best practices related to Online Support Groups (OSGs), Patient Portals and Personal Health Records (PHRs), and various forms of telehealth—including telemedicine and mHealth technologies. By understanding both the opportunities and the risks, patients can make informed decisions and engage in care more safely and confidently.

Online Support Groups (OSG)

OSGs are a great resource for patients who are dealing with a major illness or who are caring for family members who are ill. Support groups help bring people together who are going through similar experiences so they can relate to each other, share stories, coping mechanisms, and helpful information (Mayo Clinic, 2025). Even though OSGs are invaluable for those suffering from physical and psychological hardships, privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity are paramount concerns. This is especially true for those suffering from substance abuse or domestic violence, where the risk of being identified can be a deterrent (Feldstern, 2022).

Sharing personal medical and health information online involves risk (Carter-Templeton et al., 2025). To protect their privacy, patients should be mindful about what they choose to share and consider using anonymous usernames or accounts when possible. It’s also essential that they use secure devices—those with strong passwords, up-to-date software, and reliable antivirus protection. When seeking online support, patients should look for online support groups that maintain strict confidentiality and anonymity policies (Feldstern, 2022). Ideally, these groups should be hosted on private, secure platforms that restrict access to verified participants and facilitators, with all members agreeing to maintain the confidentiality of discussions and shared personal information (Safety Net Project, 2020).

- Review this website to learn more about the benefits and drawbacks of support groups.

- Review this website on being safe when using video conferencing software.

- Review this website on protecting privacy and security when online.

Patient Portals and Personal Health Records (PHR)

We reviewed information on patient portals and PHRs in Chapter 5. As a reminder, patient portals are a personal health record that’s tied to an EHR (Mayo Clinic, 2024). Patient portals are managed by providers or healthcare organizations that give you the ability to access your medical records and seamlessly communicate with providers. Sometimes, patients can add information to patient portals.

PHRs are health records that patients manage independently. They are not tied to EHRs or healthcare organizations. Users have to input all data into PHRs independently. They can also share PHRs with family members, caregivers, and healthcare professionals (Mayo Clinic, 2024).

- Review this website for more information on how patients can be safe when using Patient Portals.

- Review this website for information on how to keep sensitive health information (PHR) on devices safe.

Telehealth

We discussed telehealth in detail in Chapter 2. Telehealth is an umbrella term that includes a wide range of technologies and services designed to deliver healthcare remotely. Its subcategories include telemedicine (real-time care from healthcare providers), asynchronous (store-and-forward technologies like sending images or messages for later review), remote patient monitoring (tracking vital signs and health data from home), and mHealth (mobile health apps that support wellness and disease management).

Telehealth Privacy, Security, and Confidentiality: Telemedicine

Even though telemedicine has become an essential tool for expanding access to care, there are valid concerns around privacy, security, and confidentiality. Patients are often required to share sensitive health information, sometimes from their own homes, using personal devices and perhaps unsecured networks. Without proper protections in place, there is an increased risk of data breaches, unauthorized access, or accidental disclosures. These concerns can lead to hesitancy in using telehealth services, which may ultimately impact patients’ willingness to seek care or disclose important information. For telehealth to be both effective and trustworthy, healthcare providers must prioritize data privacy and security—and patients must be educated on how to protect themselves when engaging in virtual care.

-

Review this website for information on how patients can protect their data and privacy when using telehealth.

-

Review this website for information on patient telehealth privacy and security tips.

Telehealth Privacy, Security, and Confidentiality: mHealth

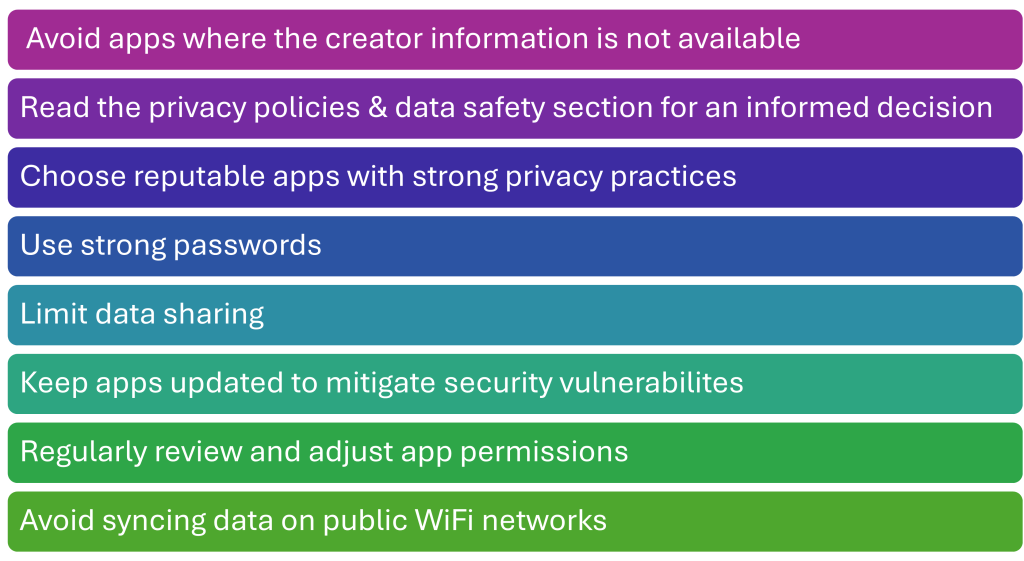

We discussed mHealth in detail within Chapter 5. Unfortunately, like all technology, mHealth technology may have potential security issues. mHealth apps collect a plethora of personal information, much more than users realize. This data is used for a variety of purposes, including personalization of plans and health recommendations, research on health trends and potential new interventions, and targeted advertising relevant to user interests (University of British Columbia, 2025). The developer informs the user of the terms of use (including the use of personal health information) and requires a confirmation agreement before the app can be used.

In a recent study, 48% of mHealth users and 84% of non-mHealth users expressed concern about sharing data within mHealth applications (Kheirinejad et al., 2022). Privacy risks associated with mHealth apps include data breaches from cyberattacks, sharing your data with third-party companies, and retaining data indefinitely even if you delete the app (University of British Columbia, 2025). Graphic 5.1 details practical security tips you and your patients can utilize when using mHealth apps.

Graphic 5.1 – mHealth Security Tips

-

Review this website for tips when using mHealth apps.

-

Review this website for more details on privacy and security when using mHealth apps.

-

Review this website for information on the privacy and security of wearable tech.

Conclusion

In today’s rapidly evolving digital healthcare environment, safeguarding patient privacy and securing health information is more critical than ever. Nurses, as trusted professionals and patient advocates, play a pivotal role in ensuring that legal standards are upheld when it comes to protecting patient data. Understanding key legislation such as HIPAA and HITECH is foundational to maintaining compliance and trust in the healthcare system.

However, security and privacy are not only the responsibility of healthcare organizations and providers; patients need to understand the risks and be proactive. Nurses are uniquely positioned to educate patients about these risks and empower them to make safe, informed decisions about their health information.

Ultimately, maintaining the confidentiality and security of protected health information (PHI) protects not just individual patients but the integrity of the healthcare system as a whole. By combining policy, technology, and education, we can create a safer, more transparent, and more patient-centered healthcare experience, one where privacy and trust are never compromised.

References:

- Alexander, S. Frith, K. H., & Hoy, H. (2019). Applied clinical informatics for nurses (2nd ed.), Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- American Nurses Association. (2024). Code of ethics for nurses. https://codeofethics.ana.org/provisions

- Burke, T. (2010). The health information technology provisions in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009: implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974), 125(1), 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491012500119

- Carter-Templeton, H., Alexander, S., & Frith, K. (2025). Applied clinical informatics for nurses (3rd ed.). Jones and Bartlett Learning.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/hipaa.html

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2016). Security risk analysis tip sheet: Protect patient health information. https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/legislation/ehrincentiveprograms/downloads/2016_securityriskanalysis.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2021a). Are you a covered entity? https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Administrative-Simplification/HIPAA-ACA/AreYouaCoveredEntity

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2021b). Medicare Promoting Interoperability program requirements for 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/pi-requirements-infographic-2021.pdf

- Conn, J. (2016). Hospital pays hackers $17,000 to unlock EHRs frozen in “ransomware” attack. http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20160217/NEWS/160219920

- Feldstern, N. (2022). Assessing anonymity: Privacy in online mental healthcare and support groups. Tulane Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property, 24. https://journals.tulane.edu/TIP/issue/view/422

- Health Information Management Systems Society. (2021). Interoperability in healthcare. https://www.himss.org/resources/interoperability-healthcare

- Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society. (2023). Cybersecurity in healthcare. https://www.himss.org/resources/cybersecurity-healthcare

- HealthIT. (2013). The path to interoperability. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/factsheets/onc_interoperabilityfactsheet.pdf

- HealthIT. (2015). Guide to privacy and security of electronic health information. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/privacy/privacy-and-security-guide.pdf

- HealthIT. (2017). Permitted uses and disclosures: Exchange for health oversight activities 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 164.512(d). https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/phi_permitted_uses_and_disclosures_fact_sheet_012017.pdf

- HealthIT. (2021). Health IT legislation. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/laws-regulation-and-policy/health-it-legislation

- Henricks, W. H. (2011). “Meaningful use” of electronic health records and its relevance to laboratories and pathologists. Journal of Pathology Informatics, 2(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.4103/2153-3539.76733

- HIPAA Journal. (2023). What is the HITECH Act? https://www.hipaajournal.com/what-is-the-hitech-act/

- Kheirinejad, S., Alorwu, A., Visuri, A., & Hosio, S. (2022, September 6). Contrasting the expectations and experiences related to mobile health use for chronic pain: Questionnaire study. JMIR Human Factors 9(3):e38265. https://doi.org/10.2196/38265

- Mayo Clinic. (2024, August 15). Personal health records and patient portals. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/personal-health-record/art-20047273

- Mayo Clinic. (2025, March 27). Support groups: Make connections, get help. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/support-groups/art-20044655

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2025a). Know the science: Finding health information on mobile health apps. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/know-science/finding-and-evaluating-online-resources/finding-health-information-on-mobile-health-apps/introduction

- National Institutes of Health. (2007a). To whom does the privacy rule apply and whom will It affect? https://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/pr_06.asp

- National Institutes of Health. (2007b). What health information is protected by the privacy rule? https://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/pr_07.asp

- Safety Net Project. (2020). Online support groups for survivors. National Network to End Domestic Violence. https://www.techsafety.org/online-groups

- University of British Columbia, (2025, May 1). Balancing wellness and privacy: A guide to digital health apps. https://privacymatters.ubc.ca/news/balancing-wellness-and-privacy-guide-digital-health-apps

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1994). Confidentiality of patient records for alcohol and other drug treatment. http://adaiclearinghouse.net/downloads/TAP-13-Confidentiality-of-Patient-Records-for-Alcohol-and-Other-Drug-Treatment-103.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). HITECH Act enforcement interim final rule. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/hitech-act-enforcement-interim-final-rule/index.html

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). Improving the cybersecurity posture of healthcare in 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/blog/2022/02/28/improving-cybersecurity-posture-healthcare-2022.html

- U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). Patient bill of rights. Retrieved August 3, 2025 from https://www.state.gov/patient-bill-of-rights-and-responsibilities

Media Attributions:

- Discover Virtual Support Groups by Mental Happy is licensed under a Creative Commons-Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.

- Gavel and Stethoscope by George Hodan has a public domain license.

OER Resources Utilized in this Section:

- Valaitis, K. (2023). Exploring the U.S. healthcare system. University of West Florida. Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.uwf.edu/ushealthcaresystem/ Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

The use of telecommunication and information technology to provide access to health assessment, diagnosis, intervention, consultation, supervision, and information across distance.

Transmission of health information and services via mobile technology.