5 Digital Patient Engagement

Laura K. Garner-Jones

Chapter 5 Overview

- Patient engagement & empowerment and shared decision-making

- Tools to support and engage patients

- MHealth applications

- Social media

- Personal Health Records (PHRs)

- Health literacy

Introduction

We are living in the information age, where people expect quick access to knowledge and immediate answers. This expectation extends to healthcare. Patients increasingly prefer not to rely solely on providers for information. Instead, they turn to technology to independently research health conditions, explore treatment options, and access their personal health data. This shift reflects a growing movement known as patient engagement. Patient engagement refers to a patient’s willingness and ability to actively participate in their care by engaging and collaborating with healthcare providers. When patients are able to engage and collaborate with providers, it ensures that their unique perspective is reflected in their care plan and enhances both their health outcomes and overall healthcare experience. To support this, healthcare professionals must be prepared to listen to patients’ ideas, preferences, and limitations while also offering expert guidance (McGonigle & Mastrian, 2025).

Similarly, patient empowerment is a process that supports a patient’s active participation in making informed healthcare decisions to improve their quality of life (Acuna Mora et al., 2022). Patient empowerment includes shared decision-making and is especially valuable in managing chronic diseases. Wiles et al. (2022) indicated that when patients are involved in decisions about their health and can access tools that can help them understand, cope, and manage health in their lives, it can increase compliance with their plan of care.

Technology can play a vital role in providing and supporting patients in their healthcare journey. To provide patients with access to their medical records and educational resources, patient portals are used. Health information on the internet and social media can provide videos, interactive graphics, and written materials that can help patients better understand their conditions and treatment options. Mobile applications and wearable devices can be used to help patients track their health status, monitor symptoms, and adhere to treatment plans (Buvik et al., 2019). Technology has the potential to enhance patient education, patient engagement, and patient empowerment. It can also facilitate shared decision-making and improve health outcomes by providing patients with timely and accessible educational resources, increasing their engagement in their own care, and promoting better communication between patients and healthcare providers.

Tools to Support Patient Engagement and Self-Management

In today’s digital world, patients have more opportunities than ever to take an active role in managing their health. Tools such as mobile health (mHealth) applications, social media platforms, and personal health records (PHRs) empower individuals to monitor their well-being, access reliable health information, communicate with providers, and make informed decisions about their care. These technologies support patient engagement and self-management by offering convenient, user-friendly ways to stay connected, educated, and proactive about personal health. This section explores how each of these tools (mHealth, social media, and personal health records) contributes to improved outcomes, greater autonomy, and enhanced collaboration between patients and healthcare professionals.

Mobile Health (mHealth)

As discussed briefly in Chapter 2, mHealth is a subdivision of telehealth and is defined as the use of mobile devices to deliver healthcare services and information (Rowland et al., 2020). It is estimated that there are over 350,000 mobile apps and 63.4% of adults in the U.S. have used a mHealth app in the past year (National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, 2025a).

mHealth uses mobile technologies, including smartphones, tablets, and computers, to utilize health applications that can help support user engagement and self-management in their health. In addition, some apps can provide education, digital therapies, and support clinical diagnosis or decision-making (Rowland et al., 2020). Sometimes the mobile technologies are connected to equipment or wearables that collect data; examples include smartwatches and smart scales. Common mHealth apps can help users with mental health, provide reminders to take medications, and track health and fitness.

mHealth is different, but closely associated with Remote Patient Monitoring (RPM), also discussed in Chapter 2. Both mHealth and RPM fall under the telehealth umbrella. The difference between mHealth and RPM is in who manages the data. In mHealth, applications are intended for individual use and are related to monitoring or informing about a variety of healthy activities, such as calorie counting or exercise (Aungst et al., 2014; Martinez-Pérez et al., 2013). Some mHealth apps can share data with healthcare providers, but ultimately, the app, data, and permissions are managed by the user.

RPMs are managed by companies or healthcare providers, and data is collected and transmitted to a healthcare provider in a remote location. RPMs are typically utilized for monitoring, chronic disease management, and diagnosis (Carter-Templeton et al., 2025). An example of RPM is diabetic systems that track blood sugar and insulin and send data to the remote provider. Other examples include home care patients whose heart rhythm and vital signs are monitored remotely, and remote fetal monitoring for high-risk pregnancies. The patient may be involved in working with equipment, but all data is automatically transmitted and evaluated by healthcare providers.

mHealth Benefits

mHealth has the potential to radically change the way healthcare services are delivered (Carter-Templeton et al., 2025). mHealth apps are widely accessible, low in cost, and can help promote healthy behaviors (Deniz-Garcia et al., 2023). Currently, the evidence surrounding mHealth is not abundant. There are only a few published studies that suggest that mHealth use improves patient outcomes, and most studies are short-term, not long-term studies. As a result, sustained improvements and long-term outcomes are unknown.

Despite this, the evidence is starting to emerge that connects mHealth applications to significant improvements in morbidity and mortality outcomes in specific cases. Preliminary evidence of mental health applications that deliver Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) indicates no outcome difference between CBT from the app versus face-to-face delivery. Preliminary evidence also shows benefits to mHealth education intervention apps for patients with heart disease, inflammatory bowel disease, pediatric tonsillectomy and forearm fractures, and in those with breast, colon, lung, prostate, and stomach cancers (Rowland et al., 2020). mHealth applications have also been connected to a moderate improvement in glycemic control (Chakranon et al., 2020).

mHealth users like participating, engaging, and using mHealth apps and find them beneficial, specifically with treatment adherence apps that offer education and medication reminders (Rowland et al., 2020). Additionally, 39% of mHealth users indicated that using mHealth apps made interacting with healthcare professionals easier (Kheirinejad et al., 2022) and helped them cope with the management of their illness (Vo et al., 2019). However, benefits can vary based on the app, the functions, and user engagement and vigilance. Table 5.1 provides a brief overview of some of the evidence and effectiveness, based on the mHealth app function.

Table 5.1 – Effectiveness of mHealth Applications (Rowland et al., 2020)

| Function | Common Use | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Support decision-making or clinical diagnosis | Self-triage

Diagnosis by using data from sensors, symptom checkers. and/or photographs |

Appropriate advice was given 80% of the time in emergent cases and 55% of the time in non-emergent cases

Diagnosis accuracy based on symptoms 34% Improved screening based on self-reported symptoms Photographic diagnosis of melanoma 82% |

| Improve clinical outcomes through behavior change and adherence with treatment | Prevention and treatment of disease through goal setting, dosing reminders, self-monitoring, and gamification | Health and fitness apps are connected to a significant reduction in body weight and BMI

Some improvements in medication adherence based on the level of user engagement and correct use of the app |

| Deliver digital therapies | Self-management of mental health conditions and insomnia by using digital therapies | Significant improvement in outcomes in the management of depression, anxiety, and stress

Improved quality of life |

| Deliver education | Disease-specific or case-specific education | Improves disease-related knowledge that supports shared decision-making

Facilitates improvement of communication with providers |

The future outlook of mHealth is promising. Health data from mHealth applications could be shared with providers to potentially facilitate an earlier diagnosis. Healthcare professionals see the potential for mHealth in managing chronic diseases like congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Carter-Templeton et al., 2025). Data from mHealth applications could also be analyzed and used in research. Optimistic researchers envision recruiting research participants within mHealth apps, and subsequently monitoring and retrieving data quickly and efficiently. These possibilities can potentially reduce research costs, improve participant numbers, and reduce recall bias (Rowland et al., 2020).

While the current evidence for mHealth is still developing, early findings suggest meaningful benefits in specific areas of patient care and self-management. As research expands and technology advances, mHealth holds great promise for enhancing clinical outcomes, empowering patients, and transforming both healthcare delivery and research efficiency.

mHealth Concerns

mHealth app content may or may not be written or reviewed by medical experts, so information and advice may be inaccurate or unsafe (National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, 2025a). mHealth privacy and security concerns will be discussed in Chapter 7.

Reliable mHealth apps created by Government agencies:

- National Library of Medicine (NLM) guide search for NLM mHealth apps

- CDC Mobile Activites (includes mHealth apps and apps for use by healthcare providers

Other sources that provide details or recommendations for mHealth apps:

mHealth and RPM Wearables

Social Media

Social media is defined as “the use of web-based and mobile technologies to turn communication into interactive dialogues” (Bradley, 2011).

Social media (SM) has significantly changed the way we exchange information and how we communicate about health. Approximately 86% of users on the internet engage in at least one of these SM activities (Chou et al., 2021):

- Visiting a social networking site: 79%

- Watching health-related videos: 41%

- Sharing health information on social media: 17%

- Participating in an online support group: 9%

There is a high percentage of U.S. adults who actively participate in SM, and the average daily use is 2 hours and 29 minutes (Chaffey, 2023). There is no significant difference in SM use across racial-ethnic minority groups and levels of education, and the use of SM by older patients is on the rise. Patients can utilize SM platforms to become empowered by engaging with experts in the field, becoming educated, advocating for care, and connecting with each other in peer groups (Chirumamilla & Gulati, 2021). Healthcare organizations and public entities can reach a wide public audience by promoting their SM presence and sharing high-quality health information on SM. By doing so, information inequities, health disparities, and misinformation can be reduced (Chou et al., 2021).

How Nurses Can Leverage Social Media for Patient Engagement

-

-

-

Join support groups: Suggest that patients join online communities and peer-support groups related to their health conditions to connect with others, share experiences, and learn from each other. Mikolajczak-Degrauwe et al. (2023) found that peer support groups improved participants’ well-being, self-confidence, resilience, and development of positive coping skills. In addition, peer support groups decreased participants’ anxiety, depression, loneliness, and stress.

-

Follow trusted healthcare professionals and organizations: Encourage patients to follow healthcare professionals and organizations on social media to access reliable health information and updates. Reliable information from SM has been found to be useful in supporting diagnoses, managing conditions, monitoring treatments, and preventing disease (Gupta et al., 2022).

-

Engage in educational content: Patients can share information, tips, and advice related to their health conditions. Nurses can also encourage patients to participate in discussions and ask questions. Naslund et al. (2017) found that SM aided patients in their effort to quit smoking. Those who engaged in tailored content within SM had a higher prevalence of abstinence, had fewer relapses, and an increased number of quit attempts.

-

-

Social Media Concerns

Not all information obtained on social media accounts can be reliable. Patients should remember the following (National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, 2025b):

Verify that social media accounts are what they claim to be:

-

-

- Use the link from the organization’s official website to go to its social networking sites.

- Look for SM symbols that indicate an account has been verified, for example, Instagram uses a blue badge with a white check mark.

-

Verify the source of the information & check the sponsor’s website:

-

-

- Health information on SM is brief; visit the sponsor’s website for information. Also consider whether the information is reliable. Ask these five questions:

-

- Who created the site? Can you trust them?

- What is the site promising or offering? Are they too good to be true?

- When was the information written or reviewed? Is it up to date?

- Where does the information come from? Is it based on scientific research?

- Why does the site or app exist? Is it selling something?

-

- Health information on SM is brief; visit the sponsor’s website for information. Also consider whether the information is reliable. Ask these five questions:

-

Personal Health Record (PHR)

The ability of individuals to easily and securely access and use their health information electronically increases engagement, improves outcomes, and advances person-centered health (Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT, 2020). Personal Health Records (PHRs) are digital tools that let people keep track of their health information in one place. They include details like (Mayo Clinic, 2024):

-

- Contact information for the user and their family

- A list of providers

- Diagnosis, medications, allergies, and immunizations

- Procedures, lab, and test results

- Personal & family medical history

- Living will and advance directives

There are two types of PHRs: Standalone PHRs and patient portals

- With a standalone PHR, users fill in their own information from their own records. Patients can add diet/exercise information and track progress over time; they can also share the information with healthcare providers. Some PHRs can accept data from outside sources like laboratories or providers, and the information is typically stored on a computer or on the internet.

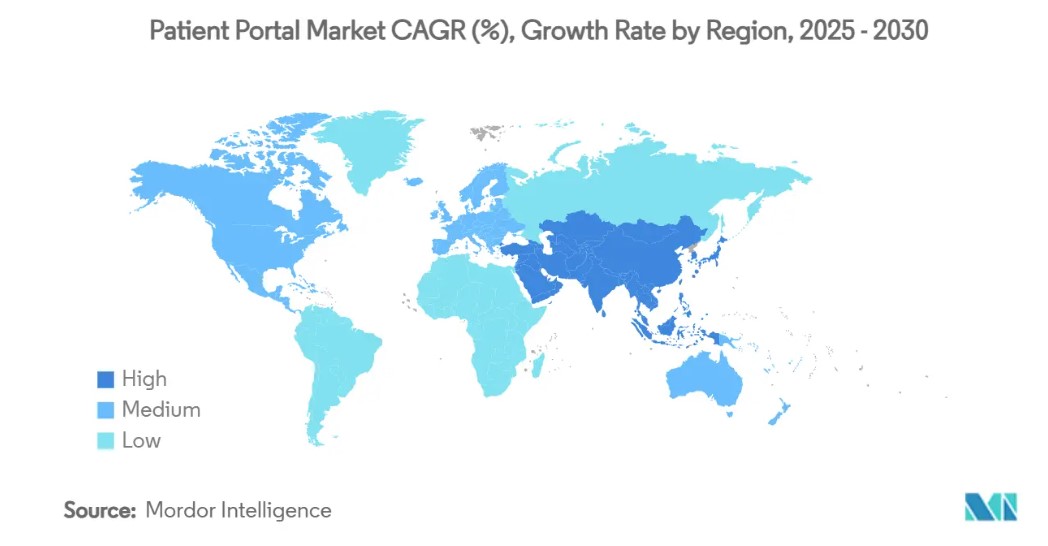

- Patient portals are connected to providers or healthcare organizations’ electronic health record (EHR) systems. Patients can access their records through a secure portal and see provider notes and assessments, labs, or due dates for screenings. Patient portals are becoming popular, and are projected to see expansive growth over the next 5 years within industrialized international countries (See graphic 5.1)

(Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, 2019)

Graphic 5.1 – Projected International Growth of Patient Portals

PHR Benefits

PHRs empower users to take an active role in managing their health. Additional benefits include:

-

-

- Better communication with healthcare providers

- Improved care coordination and continuity across settings

- Personalized treatment decisions based on complete health histories

- Convenient access and portability of health data

- Fewer medical errors and duplicate tests

- Enhanced patient safety and outcomes

-

PHRs allow users to take charge of their health by actively managing and monitoring their well-being. Tracking health progress by monitoring health metrics such as blood pressure, heart rate, weight, and blood glucose levels, patients gain valuable insights into their overall health. In addition, patients can set health goals, such as weight management, physical activity targets, or dietary improvements. PHRs provide a platform to record, track, and monitor these goals, offering tools like reminders, action plans, and visual representations such as graphs and charts. These tools help users assess their progress, celebrate milestones, and make adjustments as needed, ultimately leading to more personalized, proactive, and effective healthcare management.

Some PHRs offer seamless integration with wearable devices, fitness trackers, and health apps, enabling users to automatically capture and record health metrics. By syncing data from these devices to their PHR, individuals can maintain a comprehensive view of their health status. This integration not only simplifies the tracking process but also enhances the accuracy of health monitoring by reducing manual entry errors.

PHR Challenges

Despite the benefits, there are challenges with PHRs:

-

-

- Building and/or maintaining a PHR is necessary to keep the record accurate. This takes time. If your PHR is not part of a patient portal, you may have to input the information yourself (United States of Health Care, n.d.).

- Interoperability and compatibility issues (see Chapter 6) due to differing PHR systems and formats.

- Privacy and data security risks require strict safeguards and regulatory compliance. These concerns will be discussed further in Chapter 7.

-

Watch this video for more information on the benefits and use of PHRs.

Health Literacy

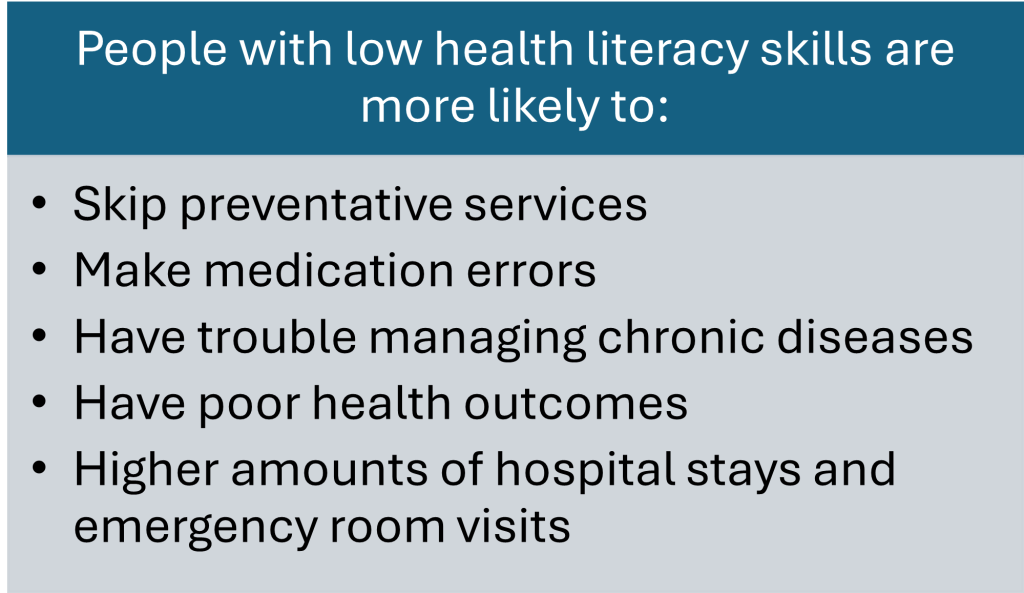

Health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024c).

Nearly 9 out of 10 adults struggle with health literacy (CDC, 2024a; National Library of Medicine, n.d.). Individuals with limited health literacy can encounter challenges interpreting basic health information, such as hospital discharge and medication dosing instructions. Limited health literacy increases healthcare costs and results in higher morbidity and mortality. It has been estimated that improving health literacy could prevent nearly 1 million hospital visits and save over $25 billion a year (United Health Group, 2020).

Seniors, who utilize a high amount of health care services, have more chronic conditions and take more medications than any other age group, have the lowest health literacy and therefore the highest risk of negative health consequences (United Health Group, 2020).

Why is Health Literacy so Important?

Health literacy is important for everyone because, at some point in our lives, we all need to be able to “find, understand, and use health information and services” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024c). Taking care of our health and well-being is something we do every day, not just when we access healthcare services. Health literacy can help prevent health problems and better manage health problems when they arise (National Institute of Health, 2025).

Everyone, even those who normally have high literacy skills or who are educated, are at risk for misunderstanding health information if they are stressed, ill, are diagnosed with a serious illness, or the topic is emotionally charged or complex (CDC, 2024b; National Institute of Health, 2025; National Library of Medicine, n.d.). In these situations, individuals “have trouble remembering, understanding, and using that information” (National Library of Medicine, n.d.).

Examples of patients who are health literate include those who can read and understand discharge instructions, take the right dose of medicine at the right time of day or manage multiple medications, understand and follow pre-surgical instructions, and have the ability to look up reliable health-related information on the internet. People who are health literate are more likely to make informed health decisions, are healthier, and live longer than their counterparts (National Library of Medicine, n.d.).

See firsthand, people who talk about their struggles with health literacy.

Want to know more? Here is a great overview video on health literacy from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

How Can Nurses Help with Health Literacy?

It is our duty as nurses to ensure that the care we provide to patients takes into consideration their unique needs and attributes, in other words, person-centered care. The American Nurses Association (2024) Code of Ethics Provision 2 indicates that as nurses, we should be providing patients opportunities to participate in assessing, planning, and implementing their plan of care. In addition, if there is conflict, nurses should help to resolve the conflict, remain committed to the patient, and advocate for additional resources if needed.

To truly honor person-centered care and uphold our ethical responsibility, we must recognize and respond to each patient’s ability to understand and engage with health information. Health literacy, the ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services, plays a key role in how well patients can participate in their care. Being aware of health literacy problems is a crucial component for helping patients achieve positive health outcomes (Satana et al., 2021).

Nurses can help with health literacy by:

1.

Avoid blaming patients for not understanding health-related information or instructions (National Institute of Health, 2025). Healthcare is complex; can you imagine getting a chronic disease diagnosis and how difficult it may be to remember everything the provider discussed, find resources, and add 4 or 5 medications (dealing with additional side effects) into an already difficult and demanding life routine? Even though we are nurses and understand the terminology, the medications, and the diseases, if we were a patient, we could have difficulty navigating a life-changing diagnosis.

2.

Nurses play a significant role in ensuring understanding in the healthcare setting. Without clear communication, we cannot expect patients to adopt healthy behaviors and recommendations (Satana et al., 2021). When communicating health-related information to patients, you may believe that you are communicating clearly and accurately, but do you know the health literacy of your patients and their families? Are you rushing through those discharge instructions? Are you sure that your message is clearly understood? These variables can be compounded when patients think and affirm that they understand, but are hesitant to ask questions to confirm their understanding (National Institute of Health, 2025). Communicating clearly helps patients understand health information so they can make well-informed health decisions (National Library of Medicine, n.d.).

Some things nurses can do to ensure that health information communication is clear include:

- Build your health information communication skills; there are a variety of free online options.

- Use the “Teach Back” method, a communication strategy endorsed by the American Medical Association and Joint Commission has been connected to improved communication, compliance, engagement, and patient safety (Badaczewski et al., 2017). More information from AHRQ on the teach-back method.

- Use certified interpreters who can adapt to your intended audience’s language preferences, communication expectations, and health literacy skills. Read more about why using certified interpreters is important and why you should avoid relying on machine translation.

3.

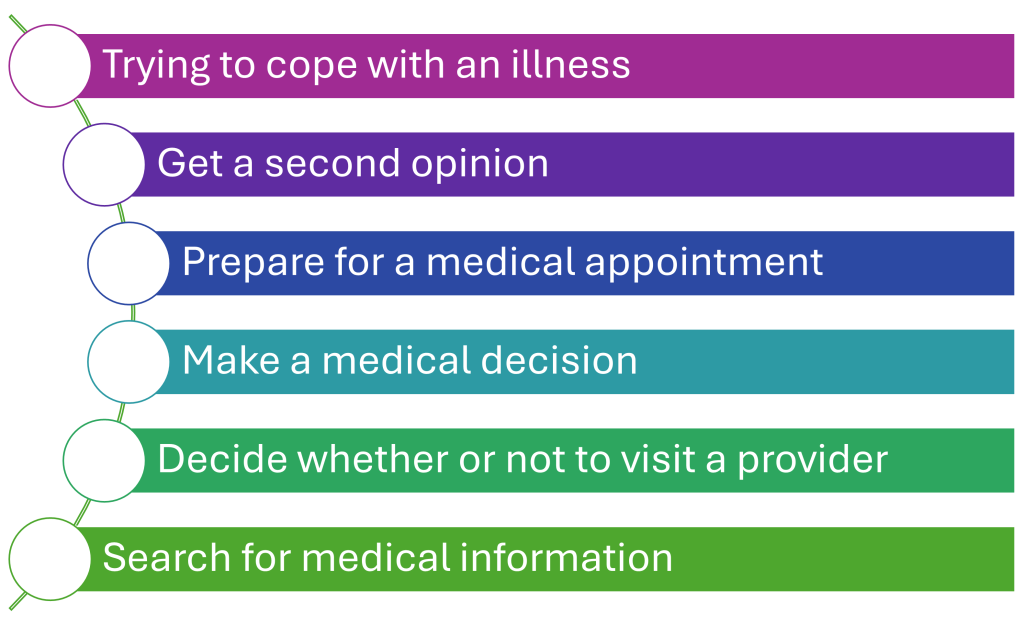

Educate patients on how to search for quality health information. Patients do not always turn to healthcare professionals for health information. Friends and family, the internet (social media and websites), and health applications are ways that patients access health information (Alduraywish et al., 2020). The internet has become a significant source of health information for patients. Hua et al. (2022) found that more than two-thirds of people who use the internet use it to search for health information, and most start with a general search engine instead of a dedicated medical information website. Yigsaw et al. (2020) highlighted the reasons that people turn to the internet to search for health information (See Graphic 5.2).

Graphic 5.2 – Reasons Individuals Look for Health Information on the Internet

While the internet can increase access to information and improve patient engagement in their health, the internet is an unregulated space, and the quality, accuracy, and reliability of health information vary widely. Health misinformation is prevalent and includes a wide variety of topics, including lifestyle and wellness choices, vaccines, chronic disease conditions, eating disorders, and medical treatments (Suarez-Liedo & Alvarez-Galvez, 2021). The National Institute of Health (2025) has indicated that it is increasingly difficult for people to separate evidence-based information online from misinformation. As nurses, we should educate patients on identifying accurate and reliable online health information. The websites listed in Table 5.2 are a great way to start. In addition, nurses can provide patients with quality websites they can navigate to obtain appropriate online health information (See Table 5.3).

Table 5.2 – Resources for Patients: Identifying Accurate and Reliable Health Information Online

Table 5.3 – Resources for Patients: Quality Websites

|

|

|

|

|

|

Online health information can result in negative consequences:

- Unnecessary office visits

- Delays in care

- Treatment changes

- Harmful treatments

- Increased healthcare costs

- Increased patient anxiety

- Medical mistrust

(Yigsaw et al., 2020)

Conclusion

In today’s digital world, patients have more ways than ever to take part in their own healthcare. Tools like mHealth, social media, and patient portals can help patients stay informed, monitor their health, and work with providers to make better decisions. These tools have the potential to improve communication, support healthier behaviors, and lead to better outcomes, but they also come with challenges such as misinformation and privacy concerns.

As future nurses, it is important to understand both the benefits and limitations of these technologies. Nurses play a key role in guiding patients toward reliable resources, making health information easier to understand, and encouraging patients to take an active role in their care. By combining technology with compassionate, person-centered care, nurses can help patients feel more empowered, more engaged, and better supported in their health journey.

References:

-

Acuña Mora, M., Sparud-Lundin, C., Moons, P., & Bratt, E. (2022). Definitions, instruments and correlates of patient empowerment: A descriptive review. Patient Education and Counseling, 105(2), 346-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.06.014

-

Alduraywish, S. A., Altamimi, L. A., Aldhuwayhi, R. A., Alzamil, L. R., Alzeghayer, L. Y., Alsaleh, F. S., Aldakheel, F. M., & Tharkar, S.(2020). Sources of health information and their impacts on medical knowledge perception among the Saudi Arabian population: Cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(3): e14414. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32191208/

-

American Nurses Association. (2024). Code of Ethics for Nurses: Provision 2. https://codeofethics.ana.org/provision-2-1

-

Aungst, T. D., Clauson, K. A., Misra, S., Lewis, T. L., & Husain, I. (2014). How to identify, assess, and utilize mobile medical applications in clinical practice. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 68(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12375

-

Badaczewski, A., Bauman, L. J., Blank, A. E., Dreyer, B., Abrams, M. A., Stein, R. E. K., Roter, D. L., Hossain, J., Byck, H., & Sharif, I. (2017, July). Relationship between teach-back and patient-centered communication in primary care pediatric encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 100(7):1345-1352. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5466453/

-

Bradley, A. (2011, March 8). Defining social media: Mass collaboration is its unique value [Blog] Gartner Blog Network. https://blogs.gartner.com/anthony_bradley/2011/03/08/defining-social-media-mass-collaboration-is-its-unique-value/#:~:text=Though%20you%20can%20do%20many,been%20able%20to%20effectively%20collaborate

-

Buvik, A., Bugge, E., Knutsen, G., Småbrekke, A., & Wilsgaard, T. (2019, September). Patient reported outcomes with remote orthopaedic consultations by telemedicine: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 25(8), 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633×18783921

-

Carter-Templeton, H., Alexander, S., & Frith, K. H. (2025). Applied clinical informatics: For nurses. (3rd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024a). Talking points about health literacy. https://www.cdc.gov/health-literacy/php/about/tell-others.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/shareinteract/TellOthers.html

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024b). Understanding health literacy. https://www.cdc.gov/health-literacy/php/about/understanding.html

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024c). What is health literacy? https://www.cdc.gov/health-literacy/php/about/index.html

-

Chaffey, D. (2023). Global social media statistics research summary 2023. Smart Insights. www.smartinsights.com/social-media-marketing/social-media-straegy/new-global-social-media-research

-

Chakranon, P., Lai, Y. K., Tang, Y. W., Choudhary, P., Khunti, K., Lee, S. W. (2020, December 12) Distal technology interventions in people with diabetes: An umbrella review of multiple health outcomes. Diabetic Medicine, 37(12). 1966–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14156

-

Chirumamilla, S., & Gulati, M. (2021). Patient education and engagement through social media. Current Cardiology Reviews, 17(2):137-143. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573403X15666191120115107

-

Chou, W. S., Gaysynsky, A., Trivedi, N., & Vanderpool, R. C. (2021). Using social media for health: National data from HINTS 2019. Journal of Health Communication, 26(3), 184-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1903627

-

Deniz-Garcia, A., Fabelo, H., Rodriguez-Almeida, A. J., Zamora-Zamorano, G., Castro-Fernandez, M., Alberiche Ruano, M. D. P., Solvoll, T., Granja, C., Schopf, T. R., Callico, G. M., Soguero-Ruiz, C., Wägner, A. M. & the WARIFA Consortium. (2023, May 4). Quality, usability, and effectiveness of mHealth apps and the role of artificial intelligence: Current scenario and challenges. J Med Internet Res. 25. e44030. https://doi.org/10.2196/44030

-

Gupta, P., Khan, A., & Kumar, A. (2022). Social media use by patients in health care: A scoping review. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 15(2), 121-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2020.1860563

-

Hua, H. U., Rayess, N., Li, A. S., Do, D., & Rahimy, E. (2022). Quality, readability, and accessibility of online content from a Google search of “macular degeneration”: Critical analysis. Journal of Vitreoretin Disorders 6(6):437-442. https://doi.org/10.1177/24741264221094683

-

Kheirinejad, S., Alorwu, A., Visuri, A., & Hosio, S. (2022, September 6). Contrasting the expectations and experiences related to mobile health use for chronic pain: Questionnaire study. JMIR Human Factors 9(3):e38265. https://doi.org/10.2196/38265

-

McGonigle, D. & Mastrian, K. G. (2025). Nursing informatics and the foundation of knowledge (6th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

-

Martinez-Perez, B. de la Torre-Diez, I., & Lopez-Coronado, M. (2013). Mobile health applications for the most prevalent conditions by the World Health Organization: Review and analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(6), e120. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2600

-

Mayo Clinic. (2024, August 15). Personal health records and patient portals. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/personal-health-record/art-20047273

-

Mikolajczak-Degrauwe, K., Slimmen, S. R., Gillissen, D., de Bil, P., Bosmans, V., Keemink, C., Meyvis, I., & Kuipers, Y. J. (2023, September 15). Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of peer support among disadvantaged groups: A rapid scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Science, 10(4). pp. 587-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2023.09.002

-

Naslund, J. A., Kim, S. J., Aschbrenner, K. A., McCulloch, L. J., Brunette, M. F., Dallery, J., Bartels, S. J., & Marsch, L. A. (2017). Systematic review of social media interventions for smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors, 73. pp 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.002

-

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2025a). Know the science: Finding health information on mobile health apps. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/know-science/finding-and-evaluating-online-resources/finding-health-information-on-mobile-health-apps/introduction

-

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2025b). Know the science: Finding health information on social media. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/know-science/finding-and-evaluating-online-resources/finding-health-information-on-social-media/five-quick-questions-to-ask-when-checking-out-social-media-for-health-information

-

National Institute of Medicine. (2025, February 25). Health literacy. https://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear-communication/health-literacy

-

National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). An introduction to health literacy. Retrieved July 29, 2025 from: https://www.nnlm.gov/guides/intro-health-literacy

-

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. (2019). Personal health records: What healthcare providers need to know [PDF Fact Sheet]. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/about-phrs-for-providers-011311.pdf

-

Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT. (2020). Health IT playbook. HealthIT.gov. https://www.healthit.gov/playbook/

-

Rowland, S. P., Fitzgerald, J. E., Holme, T., Powell, J., & McGregor, A. (2020). What is the clinical value of mHealth for patients? NPJ Digit Med. 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0206-x

-

Santana, S., Brach, C., Harris, L., Ochiai, E., Blakey, C., Bevington, F., Kleinman, D., & Pronk, N. (2021, December). Updating health literacy for healthy people 2030: Defining its importance for a new decade in public health. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 27(6): S258-S264. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001324

-

Suarez-Liedo, V. & Alvarez-Galvez, J. (2021). Prevalence of health misinformation on social media.: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(1), e17187. https://doi.org/10.2196/17187

-

United Health Group. (2020, October). Improving health literacy could prevent nearly 1 million hospital visits and save over $25 billion a year [Brief]. https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/content/dam/UHG/PDF/About/Health-Literacy-Brief.pdf

-

United States of Health Care. (n.d.). Your personal health record (PHR): A guide to maintaining health history. Retrieved July 31, 2025 from https://unitedstatesofhealthcare.com/personal-health-record-phr-create-maintain-your-history/

-

Vo, V., Auroy, L., & Sarradon-Eck, A. (2019). Patients’ perceptions of mHealth apps: Meta-ethnographic review of qualitative studies. JMIR mHealth and uHEalth, 7(7). e13817. https://doi.org/10.2196/13817

-

Wiles, L. K., Kay, D., Luker, J. A., Worley, A., Austin, J., Ball, A., Bevan, A., Cousins, M., Dalton, S., Hodges, E., Horvat, L., Kerrins, E., Marker, J., McKinnon, M., McMillan, P., Pinero de Plaza, Maria Alejandra, Smith, J., Yeung, D., & Hillier, S. L. (2022). Consumer engagement in health care policy, research and services: A systematic review and meta-analysis of methods and effects. PloS One, 17(1), e0261808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261808

-

Yigzaw, K. Y., Wynn, R., Marco-Ruiz, L., Budrionis, A., Oyeyemi, S. O., Fagerlund, A. J., & Bellika, J. G. (2020). The association between health information seeking on the internet and physician visits (The seventh Tromsø study – part 4): Population-based questionnaire study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(3): e13120. https://doi.org/10.2196/13120

Media Attributions:

-

Defense Health Agency (DHA) Connected Health. (2021, June 9). Personal Health Record (PHR) for patients [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xmsYHsyyJdc

-

Health and Fitness Apps On Mobile Phone by Forth Edge is licensed under Creative Commons BY 2.0

-

Johns Hopkins AI. (2012, August 23). AMA health literacy video: Short version [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubPkdpGHWAQ&t=239s

-

Patient Portal Market CAGR% by Mordor Intelligence is licensed CC BY 4.0 International

-

Social Media Applications by Rawpixel is in the Public Domain

-

Testing by Delesign Graphics is licensed under a CC-BY 4.0 International license.

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, October 21). 5 things to know about health literacy [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BG-iY-em7mk

OER Resources Utilized in this Section:

-

Bowen, C., Draper, L., & Moore, H. (2024). Fundamentals of nursing. OpenStaxs. https://openstax.org/details/books/fundamentals-nursing Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License

-

Gurung, S. (2024). Managerial information systems in healthcare. PressBooks. https://pressbooks.cuny.edu/profgurung. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

-

Valaitis, K. (2023). Exploring the U.S. healthcare system. University of West Florida. Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.uwf.edu/ushealthcaresystem/ Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

A patient’s willingness and ability to actively participate in their care by engaging and collaborating with healthcare providers.

process that supports a patient's active participation in making informed healthcare decisions to improve their quality of life

The practice of healthcare providers who empower patients to make healthcare decisions and state their needs and limitations.

Transmission of health information and services via mobile technology.

A software program you access using your smartphone, tablet, or other mobile device.

Devices worn on the body to monitor and track various health parameters in real-time.

The transmission of an individual's personal health and medical data to the healthcare provider in a different location for diagnosis and treatment.

A type of psychotherapy that helps individuals identify and change negative thinking patterns and behaviors to improve their mental health.

The use of web-based and mobile technologies to turn communication into interactive dialogues.

Digital tools that allow individuals to store and manage their health information, such as medical history, medications, and test results, in one accessible place.

The ability of different Health IT systems and software applications to exchange health information and use the information once it is received.

The degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.