10 Chapter 10: Political Ecology

What is political ecology and what can it tell us about natural resources sustainability? Definitions vary, but essentially political ecology is about how society structures access of different groups of people to natural resources, especially land, and how economic processes and public policies generate environmental and natural resource problems. It is not really a school of economics, and, in fact, rejects the notion that one can study the economy separate from society and nature as a whole. It is a distant relative of Marxism, also sometimes referred to as political economy, with its emphasis on inequality rooted in differences in political and economic power among groups of people. While neoclassical economics supports capitalism, political ecology critiques it. It is a very different lens that sees a fundamentally unfair world. To taste it’s flavor, try viewing the narrative cartoon The Story of Stuff.

How many oil fields or mineral deposits do you own? Do you own any agricultural or forestry land? I own 0.4 acres with some nice trees and flowers on it, and I’m considering reducing the area of grass I have to mow in favor of some nice xeriscaping. That may be more ownership of natural resources than most readers of this text possess. Yet, if you are a middle- or even working-class American, you are a “have” in a world of haves and have-nots. Even if you don’t own mineral resources or land, you probably have the spending power to acquire food, water, raw materials, and energy sufficient to meet your needs, if not your every desire. Unfortunately, billions of people do not have sufficient access to natural resources to meet their basic needs. Nearly a billion are underfed while even more are overweight, partly because of the low-quality carbohydrate-rich, cheap food that is available to them—if in large quantities. Over a billion lack access to safe drinking water and as a result suffer from deadly diseases that are completely preventable. Nearly two billion do not have access to electricity, even occasionally. Over two billion lack access to basic water sanitation like toilets and sewers. Most farmers do not own the land they till. Meanwhile, a fortunate few own or control the majority of natural resources and the economic benefits from them. They benefit from excellent ecosystem services while others live amidst environmental degradation and health risks from pollution or natural hazards. These are issues of environmental justice and natural resource allocation, and they greatly affect progress toward natural resource sustainability.

We’ll begin this discussion of political ecology with a look at the globe as a single economic system with an affluent core and an impoverished periphery. A critical look at globalization will follow by uncovering how natural resource consumption in one region can result in unsustainable resource exploitation in another. Problems of natural resource sustainability in the periphery differ in many ways from those in the core. The central issue is often land and water degradation borne of inequality, economic change imposed from outside the region, and population pressure, with population growth itself being a symptom of poverty as we explored in Chapter 5. We’ll then compare two case studies of wildlife conservation in East Africa and Alaska. In both cases, the issue is conservation for whom? We’ll finish by proceeding from diagnosis to possible cure by examining the Millennium Development Goals and progress toward achieving them.

The Global Economic System of Core and Periphery

Long before the rapid globalization of the last generation, the world was becoming a single economic system based on Western (that is, Western European and American) capitalism. Capitalism first developed in Northwest Europe, especially the Netherlands, followed by England and then France, in the 16th–18th centuries to slowly replace feudalism. It began to spread throughout western Europe and then overseas, partly through emigrant populations from Europe that pushed aside indigenous populations in the Americas, Australia, and Siberia, and partly through colonialism forced upon African and Asian populations by Europeans.

The early capitalist system enriched Europe, while impoverishing other regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa. Millions of West Africans were captured and forced into slavery in the Americas in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the 19th century, Europeans divided up Africa into colonial spheres of influence. In fact, the modern borders of Africa’s 54 nations were largely determined by the Treaty of Berlin (Germany) in 1885. The 17th–19th Century Triangular Trade system of the North Atlantic worked to the advantage of Europe while Africa’s economic development was actively undermined. Latin America, as well as the early American South, became a land of haciendas—large plantations owned by Europeans and worked by Africans or Native Americans. Viewed in this way, the American Revolution not only replaced monarchy with democracy, it also helped the American colonies escape the economic fate of many of Europe’s other overseas colonies—becoming a periphery.

A similar story can be told in Asia where Indonesia was the Dutch East Indies, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos were French Indochina, the Philippines were a Spanish and then briefly an American colony, and British India included all of South Asia. There is clear evidence that the industrial revolution in 18th–19th Century Britain in fact deindustrialized India, whose prosperous cottage industries in cotton clothing and other trades eroded away in the face of mass-produced cotton textiles from Britain. China was an open door to all imperialists where, in the Opium Wars of the 1840s and 50s, the British fired cannons at coastal cities to force the Chinese to accept imports of opium from India. Even in the 21st century, the legacy of colonialism smolders throughout the developing world.

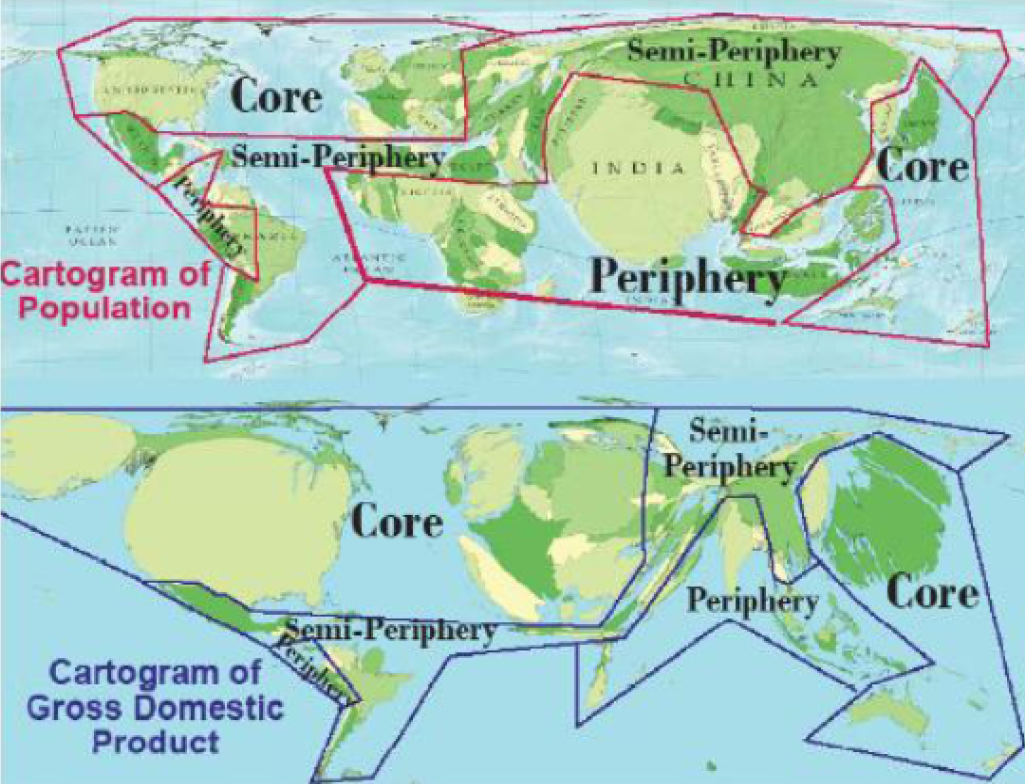

I provide this very brief review of history so that we can understand why some regions of the world—North America, Europe, the Pacific rim of Asia and Australia-New Zealand—are “developed,” while others on the wrong end of historical colonialism—Latin America, Africa, the rest of Asia, are “developing.” Acknowledging that political and economic power flow largely from a capitalist core in North America, Europe, and, more recently, Northeast Asia, political economists like Immanuel Wallerstein, father of world-systems theory, refer to the core, periphery, and semi-periphery of the world system. These are mapped in Figure 10.1, but we must remember that the map changes on a decadal time scale. For example, South Korea and former Soviet satellites of Eastern Europe that have now joined the European Union have only recently graduated to core status after centuries as semi-periphery countries with elements of industrialization, but markedly lower standards of living than in the core. Eastern China graduated from periphery to semi-periphery on the back of rapid industrialization in the late 20th Century and is currently approaching core status, even while rural backwaters of that vast country remain in the periphery. Russia today is a semi-periphery country.

It is easy to document the differences in human welfare between core, semi-periphery, and periphery. A visually interesting way to do this is to compare cartograms of world population (top of Figure 10.1) with gross domestic product (bottom of Figure 10.1). The latter is a map of the world economy, where the core looms large, and even populous peripheries in Latin America, Africa and South Asia shrink. Life expectancy, literacy rates, access to doctors, scientific productivity, and any number of other measures show similar geographical patterns of inequality. Despite the preponderance of people in the periphery, natural resources flow predominantly from the periphery to the core.

Zooming in on a region in, say, Brazil, Costa Rica, or Ivory Coast, we would find that most of the best agricultural land is owned by a small local elite with a European ancestry or historic ties to colonialists or by agribusiness corporations headquartered in the U.S. or Western Europe. How many food and drink products did you consume this week that come from tropical plantations: coffee, tea, chocolate, bananas, mangoes, pineapples? Do these plantations occupy land that could be growing food crops that would better nourish the local population? Are they economic colonies of the core in the tropical periphery?

Once the better lands are taken, land-hungry peasants (this means a small-scale subsistence farmer) scramble to find enough land to feed their families. Often they are left with less fertile or more erodible lands. They clear the forest from the hillsides; they graze cattle, camels, sheep, and goats on the margins of the desert; they farm the flood-prone lands alongside the river and the newly deposited mud at the rim of the river delta and become sitting ducks for the next typhoon. They have been marginalized; their basic needs are low on the capitalist priority list.

Globalization and Natural Resources Sustainability

Globalization has brought about a steady increase in the volume of natural resources traded among regions of the world. Does trade enhance or undermine sustainability? Let’s consider an example from forestry. Today, densely populated, affluent Japan enjoys 74 percent forest cover which provides a variety of ecosystem services locally in Japan—flood protection, soil binding, wildlife habitat, recreation, aesthetics and so on. However, Japan is the world’s leading importer of wood products with over 20 million tonnes per year reaching Japanese ports. Domestic production is only a fourth as high. The tropical forests of Malaysia and Indonesia over 1,000 miles to the south have long been a leading source. As a result, in the 1990s Indonesia lost nearly 4,000 square miles of rainforest per year in a region second only to the Amazon for species diversity. Massive fires consuming trees and soil peat and releasing millions of tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere have become a periodic disaster in the large Indonesian Islands of Sumatra and Borneo.

By importing most of its forest products, Japan gains the provisioning ecosystem services of Indonesian and Malaysian forests while simultaneously preserving the ecosystem regulation and cultural services provided by its domestic forests. Indonesia’s gain in foreign exchange from Japan comes at the expense of large costs in future natural resource and ecosystem service benefits from its depreciating natural capital endowment. In this way, trade redistributes the benefits of both natural resource use and services from ecosystems.

Closer to home, the forested New England landscape was largely cleared for agriculture in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The region developed a manufacturing economy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, then de-industrialized in the late 20th century as it gained a prominent position in the global service economy. For the last century, New England has witnessed the most extensive reforestation on the globe, primarily due to natural succession on abandoned farmlands, and is now regarded as the least polluted region in the U.S.

Like the Japanese, however, New Englanders have the economic and political power to choose to base their economy on service industries that do not require large-scale exploitation of local natural resources. Also like the Japanese, they have the purchasing power to acquire natural resources from other regions – oil from the Middle East, Canadian, and Venezuelan oil sands and fracked oil and gas shale fields in the U.S., meat and grain products from the Midwest Corn Belt, metals from Africa and Australia, and so forth. The environmental degradation associated with production of these natural resources occurs in the regions exporting them, not New England. Even pollution associated with consuming these resources, such as greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles and power plants, has environmental effects that are felt largely outside of New England. Meanwhile, New Englanders have succeeded in lobbying for legislation to limit sulfur dioxide emissions from coal-fired power plants in the Midwest that cause acid rain in New England and are actively blocking, on aesthetic grounds, wind power projects that would reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the region. Yet these greenhouse gas emissions affect the entire globe, not just New England.

The point here is not to pick on New England, a charming region that I encourage you all to visit in October when the fall foliage (borne of that reforestation trend) is in full color, but to illustrate how interregional trade in natural resources redraws the map of environmental quality—usually to the benefit of the wealthy. Core status in the global economic system sometimes allows a region to have its ecosystem service cake and eat its natural resource consumption too. Political ecologists have called this phenomenon ecologically unequal exchange and point out that environmental justice is a critical issue.

Moreover, as periphery regions increasingly specialize in natural capital-intensive industries (e.g., mining and processing of ores, petroleum production and refining, paper products, intensive agriculture), they forgo the development of human, social, and intellectual capital that accompanies growth in advanced manufacturing and services industries. Some have called this the natural resources curse.

Every locality thus has a history of natural capital appreciation and depreciation that reflects both its physical geography and its changing role in local, regional, and global economies. Globalization intensifies this dynamism by making the natural capital of each locality accessible to global markets, bringing to bear a global search for low-cost minerals, timber, crops, and energy supplies. Small-scale, locally oriented production is frequently abandoned. Traditional economies that rely heavily upon local mechanisms of social reproduction and ecosystem service provision are replaced with commodity trade at the periphery of the world economy. Often, the result is rapid depreciation of the local natural capital endowment. We call it soil erosion, land degradation, deforestation, desertification, and loss of biodiversity.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) regulates world trade, usually in the name of free trade, which we ordinarily associate with minimizing tariffs on exports and other protectionist measures that favor domestic over foreign producers. Nations of the world differ markedly, however, in labor laws and wages and in environmental protections. At its worst, free trade can become a race to the bottom, where the countries with the lowest wages and laxest regulations can produce goods the cheapest. They thereby get more foreign direct investment from multinational corporations in new production facilities and increase their exports. Meanwhile manufacturing jobs may flee from unionized regions and nations with strict environmental codes. This economic process clearly undermines sustainability goals.

The issues raised here do not prove that trade and globalization are bad, or good for that matter, for sustainability. Rather they show that trade and globalization have considerable impacts on natural resources sustainability and these impacts need to be a core component of trade agreements and negotiations, where the devil often resides in the details.

The Political Ecology of Land Degradation

Following on the earlier book The Political Economy of Soil Erosion in Developing Countries, in a classic 1987 study, Land Degradation and Society, British political ecologist Piers Blaikie and Australian geographer Harold Brookfield investigated the causes of land degradation in several localities around the globe. They found that causes are remarkably specific to the place and time of their occurrence, and so they use the term regional political ecology.

Why are lands degrading? Is it population pressure on land-based resources? Surprisingly, they found that land degradation is often more serious in sparsely populated than in densely populated regions. Why? Population growth generates economic demand for agricultural products, which must be produced somewhere, placing pressure on the land at a global scale. Populous fertile regions— like the plains and river valleys of eastern China, the deltas of southeast Asia, the Gangetic plain of northern India, the north European plain, or the American Midwest—have, through the centuries, evolved systems of intensive agriculture on lands and soils that are resilient. They can support continuous farming, if the right long-term investments in land management are implemented. To some extent, terraces, rice paddies, drainage ditches, and irrigation canals have been constructed and are maintained; manure is heavily applied; and conservation tillage has been adopted. The high population densities make abundant labor available to implement conservation measures, such as terrace construction and maintenance, which requires enormous effort. Moreover, farmland is expensive, and therefore is highly valued and degradation is guarded against.

As population and economic growth increase demand, new lands are brought under cultivation where soils may not be as resilient; in fact these may be areas where agriculture has been attempted in the past, but was not sustainable, so they reverted back to forest or grassland. This is especially true in the tropics and subtropics, where humus and nutrients are rapidly cycled into plant biomass and do not accumulate below ground in the soil like they do in temperate climates. It is also true in drier regions, as we saw with the Dust Bowl disaster in Chapter 2, where droughts leave the soil unprotected from the wind—and the rain when it finally does come in a downpour. It is also true in steep areas, where running water gains the momentum and power to strip soils away if they are not completely protected by vegetation.

These more sparsely populated areas are agriculturally marginal; they are mediocre lands brought into cultivation only after the better lands are fully developed. Usually, they are more vulnerable to land degradation. For this reason, increases in cropped area do not yield corresponding increases in harvest, because the best lands are farmed first and expansion occurs on less fertile and less resilient soils.

Looking closer, every locality has unique circumstances, not only of land characteristics and climate but of human characteristics of population, culture, and the social and economic relationships between landowners, land managers, and the land itself. The Midwestern model of the individual farmer who owns the moderate-sized farm (s)he tills does not even characterize the U.S. Midwest, where most farmers own only a minority of the land they work, renting the rest from non-farmers who may or may not live in that county. A farmer has a greater incentive to maintain the natural capital of soil on their own land than on land they rent from others.

In developing countries, some farmers are sharecroppers, giving a proportion of the harvest to the landowner as payment for use of their natural capital. In other areas, farmers may till a particular small field as a family unit but share construction and maintenance of irrigation and terracing systems, or livestock herds, with the village as a unit, where local elders dominate the group decision-making process. In other areas, young men leave for months at a time to work in mines hundreds of miles away, provide military service, or take jobs in a neighboring core country while women do almost all of the farming in the fields and pastures surrounding the village. In other areas, agriculture is export oriented, focusing on cotton, coffee, tea, or bananas and under the control of transnational corporations. In other areas, the export crop is opium or cocaine under the control of illegal cartels who may dominate the local political scene rather than the weak government in the national capital that is under pressure from the United States to pursue the losing battle to crush the drug export industry. In other areas, rapid population growth leads to the division of farms into smaller and smaller pieces until they become incapable of supporting the food, fiber, and fuel needs of a family. Sometimes, as in Rwanda, this can lead to tribal warfare over the natural resources needed for survival. In other areas, it leads to ecocide, where desperately hungry people knowingly overwork the land because the alternative is starvation.

Each of these ways in which society organizes the hard work and the application of knowledge in agricultural production greatly influences the implementation of soil conservation and other natural resource management techniques. Given this complexity and diversity, it is easy to see why Blaikie and Brookfield found that when agricultural specialists or soil scientists from core countries diagnose the problem, outline the solution, and leave, expecting their recommendations to be implemented by local farmers, the results almost universally failed. Political ecology can thus be an intricate field of study that never runs out of new situations to try to understand and hopefully improve.

The Political Ecology of Wildlife Conservation: Two Case Studies

If I were to ask you where you would find the greatest resources of wild charismatic megafauna—big exciting animals you’d like to see—two answers I’d expect to hear are the safari lands of Kenya and the wild arctic lands of Alaska. Let’s see how political ecology would view these great wildlife resources.

Kenya’s Wildlife

Every American kid, even those few who missed Lion King (or its remake using updated animation technology), knows the wildlife of the East African savannas—elephants and lions, hippos and rhinos, hyenas and zebras, and a variety of antelope, like the wildebeest. No doubt conserving these precious wildlife species is a noble endeavor consistent with natural resources sustainability. But it’s not that simple.

John Akama, a native Kisii of Kenya, studied the political ecology of wildlife conservation in Kenya’s national parks as his dissertation under my direction in 1996. By interviewing local agricultural peoples on the borders of two parks, he was able to unravel a thorny conflict of interest that threatened to undermine efforts at wildlife conservation. International organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund help keep the flow of ecotourists from North America and Europe coming and praise Kenya’s conservation efforts. Meanwhile, only a third of the rapidly growing population bordering the parks grows enough food to feed their families. There is an urgent need for more agricultural land, but the parks take up 10 percent of Kenya’s land (Figure 10.2.) Wildlife frequently wander out of the parks and damage crops, kill livestock, and injure and occasionally even kill local people. Yet they are forbidden from using force against them, and receive no compensation for damages done. Even when an overpopulated elephant herd was culled by park rangers, local people were denied the meat in the midst of drought and food shortages. Less than three percent of local people earned income from the parks. Local agriculturalists who entered the parks were arrested or shot at by rangers, always imported from another tribe in Kenya. An elderly Kamba man living on the border of Tsavo, Kenya’s largest national park in the Serengeti Plain on the Tanzania border, summarized the local feelings:

Whether they [the government] like it or not, we are going to occupy this wilderness. This land used to belong to our forefathers and since our present population has increased tremendously, the wilderness should now be opened for agricultural production (Akama et al., 1996, p. 133).

Only 10 percent of local residents surveyed felt that the park is an asset to local people, 17 percent felt the relationship between the local people and the park is good, and 12 percent felt that wildlife conservation is the most appropriate use of the park land. A majority thought the park should be abolished. These attitudes obviously run counter to those of park officials, the Kenyan government, and ecotourists.

Ecotourism was and remains Kenya’s largest source of foreign exchange, funding the modernization of Nairobi, supporting the government bureaucracy, and providing steady jobs for park personnel, some of whose primary job is to keep local farmers and herders out. Science is also at issue. Zoologists from around the world have studied the dietary, health, and reproductive requirements of East Africa’s wildlife, but few are studying how to improve agricultural productivity in savanna soils, or where best to place wells to provide safe drinking water for villagers.

Are local Africans then against conserving these wonderful wildlife species? No. Not only do they consistently assert the animals’ right to live on the land, but the tremendous herds that early European explorers found in East Africa are proof that African approaches to wildlife management were sustainable, even when they involved hunting. This was the way of life of people such as the Walianguru, whose livelihood was criminalized when the British occupied Kenya, while opening the herds up to western big game hunters including President Teddy Roosevelt, renowned as a conservationist. Perhaps the issue is not pro- vs. anti-conservation. It is conservation for whom?

Alaskan Subsistence

For Americans from the Lower 48, Alaska represents a great northern frontier, a place where the human imprint is evident, but nature, both nurturing and harsh, is dominant. It is a place where the landscape of temperate rainforest, taiga, marshland, arctic tundra, and glaciers has not been transformed into the cities and farms that dominate the Lower 48. As a result, charismatic megafauna—brown and polar bears, caribou, moose, salmon—still live in abundance in natural breeding and predator-prey relationships. Those same wildlife and landscapes draw hunters and anglers seeking optimal recreational experiences as well as tourists who just want to take it all in.

Like arctic communities elsewhere, harvesting of terrestrial and marine wildlife is a fundamental part of many Alaskan’s lives, both for food and materials and as a part of long-standing cultural traditions that establish individual and group identities. In rural Alaska, it has been estimated that the average person catches and eats an annual harvest of 120–370 pounds of fish and 80–250 pounds of birds and mammals. Because it is fundamental to people’s lives, access to Alaska’s wildlife is contested, and the laws governing such access are a core part of the social structure of the state for both Native peoples and for more recent Euro-American immigrants, especially for the quarter of Alaskans who reside in the vastness of rural Alaska beyond Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau. This case study explores the political ecology of consumptive access to Alaskan fish and wildlife.

Like elsewhere in the arctic, biological productivity and biodiversity are generally low in Alaskan ecosystems. Food chains are simple and subject to cascading effects from the harvest of a single species. Most animals are migratory. Populations fluctuate wildly. Nevertheless, Alaskan ecosystems remain vibrant. The northwestern Alaska caribou herd varies from one-half to one million animals. Salmon runs in Alaskan rivers have not declined substantially from pre-European times. Traditional subsistence and even recreational hunters and anglers are often the staunchest of conservationists, not only because their culture, livelihood, or cherished hobby is dependent upon the continued availability of wildlife but also because they have spent considerable time and energy in a direct relationship with nature that, while consumptive, is generally sustainable rather than exploitive. Demand for wild species creates a demand for wild lands that are their habitat and a resistance to urban, agricultural, and industrial development. Harvest of wild species is also less energy-intensive than agriculture, especially for the production of protein.

Harvest of Alaskan fish and wildlife is divided into dangerously fuzzy legal sets: “commercial,” “recreational/sport,” and “subsistence” (living off the land). Of all fish and game harvested in Alaska, 4 percent is subsistence, 1 percent is sport, and fully 95 percent is commercial, with a focus on the prodigious fisheries of the shallow Bering Sea that supply a majority of all fish caught in U.S. waters. There is a great deal about subsistence use of fish and wildlife in Alaska that is not recorded because of the predominance of oral tradition and because subsistence practices are extremely localized and varied, reflecting differences in both ecology and culture. For example, among ten rural Alaska communities, there are ten different wild species that rank as the most important food source: chum, sockeye, and coho salmon, whitefish, herring, halibut, caribou, moose, deer, and bowhead whale. If the top ten food sources for each of these communities are listed, 172 species appear.

The history of Native-White relationships in Alaska contains elements of the tragic history of disease, conquering, establishment of reservations, and failed assimilation that characterizes the Lower 48, but it is also different in important ways. In contrast to Great Plains Indians, for example, who no longer hunt bison because White buffalo hunters nearly exterminated them, Alaskan Natives have been partially successful in their struggle to maintain wildlife harvesting in the places their ancestors lived, while also pursuing cash incomes to supplement subsistence hunting and fishing.

The case of the Tlingit is particularly instructive. The richness of the salmon runs of southeast Alaska allowed a sedentary existence for the Tlingit and the consequent formation of social hierarchies at increasing scales from persons to houses to clans to moieties to kwaans. Clans maintained use rights to critical natural capital—salmon streams, halibut banks, hunting grounds, sealing rocks, berrying grounds, shellfish beds, canoe-landing beaches—and clan names reflect an association with a sacred geography. In their own language, they are “beings of” or “possessed by” the location where they live.

Through the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Tribes of Alaska, these tribes have been able to respond to White encroachment on fishing grounds and historic native lands by empowering traditional kwaans with functions similar to municipalities, thus gaining common property control over fishing and hunting grounds and reversing the earlier forced trend toward private ownership of farm-sized plots of land. The Alaskan Federation of Natives (AFN), formed in 1967, has acquired considerable political standing and has made protection of subsistence rights a major issue. Native Americans have struggled to assert their rights with regard to cultural survival, protection and retention of land, self-government, and to avoid the welfare state of too many of their cousins in the Lower 48. Subsistence rights to fish and wildlife are critical to all of these goals.

Nevertheless, relationships between Native Americans, Euro-Americans, and wildlife in Alaska remain as complex and contentious as anywhere in the Arctic, and laws granting priority to subsistence hunting and fishing divides the Alaskan electorate like no other issue. White urban Alaskans, 80 percent of the state population, also cherish consumptive access to fish and wildlife. While not dependent on consumption of wildlife for a livelihood or food, many residents of Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau value hunting and fishing as part of being an Alaskan and as a reason for living in Alaska despite its bad weather, extreme variations in length of daylight, and remoteness. They have invested considerably in boats, guns, tackle, even airplanes in order to get out there where their game live. Represented by groups like the Alaska Outdoor Council, urban-based hunters and anglers often oppose subsistence rights and are a major force in state politics. Recreational hunting and fishing by ecotourists is also growing and the economic value of game taken for sport is particularly high. For the millions of hunters and anglers in the Lower 48, Alaska represents a peak once-in-a-lifetime experience in the remote wilderness. Many will pay top dollar for guided access to trophy hunting for caribou and brown bear or to fly-fish for abundant salmon and trout that will not reject flies their distant Lower 48 cousins have seen again and again.

ANCSA and ANILCA. In 1971 Congress, without strong support from Alaskan natives, passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) establishing 12 regional Native American for-profit corporations and granting control of 11.6 percent of Alaskan lands, plus $962.5 million, while eliminating Native claims to the remaining 88.4 percent of Alaska. For example, 16,000 Tlingits enrolled as shareholders in Sealaska Corporation received $250 million. ANCSA states:

“All aboriginal titles, if any, and claims of aboriginal title in Alaska based on aboriginal use and occupancy . . . including any aboriginal hunting or fishing rights that may exist, are hereby extinguished.”

ANCSA was followed in 1980 by the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) that divided federally-owned lands in Alaska totaling over 200 million acres, more than 60 percent of the state, among the Bureau of Land Management (24 percent of the state), the Fish and Wildlife Service (19 percent), the National Park Service (15 percent), and the National Forest Service (6 percent). The State of Alaska manages 24 percent of the state’s land, and Native Corporations manage 10 percent, with only one percent of the land privately owned. Beyond settling the division of land management responsibilities, ANILCA also established subsistence rights to harvest wildlife as a priority over commercial and recreational uses, giving preference to rural Alaskans but no preference to native Alaskans, some of whom have urban addresses.

Sport hunting and fishing interests attempted in 1982 to have the subsistence provisions of ANILCA repealed, but urban majorities overwhelmingly supported ANILCA at the polls. In December 1989, amid controversies over the meaning of “rural,” the Alaska Supreme Court invalidated ANILCA because it explicitly grants priority to rural residents and in so doing violates the state constitution’s rule of equal access. As a result of this and the state legislature’s failure to remedy the problem, in 1992 for wildlife and in 2000 for fish, the federal government took over jurisdiction of subsistence activities on 60 percent of Alaskan lands under federal jurisdiction. They formed a six-member Federal Subsistence Board tasked with determining annual hunting and fishing regulations and customary and traditional uses. Individual bag limits and seasons that constitute the nuts and bolts of Euro-American hunting and fishing regulations have frequently been found to be incompatible with native patterns of communal harvest at key stages in wildlife migrations.

Recreational use has come into direct competition with subsistence use of fish and game in ways that reflect a certain incompatibility between rural subsistence traditions derived from a hunting and gathering lifestyle and a growing Euro-American, urban-based culture with a sporting tradition that values excitement in the catch, taking home trophies, traveling long distances, and buying expensive equipment and guides. For example, urban Alaskans and tourist hunters spend enormous sums for guided trophy brown bear hunts, leave the meat behind as inedible, and take the skulls and skins to be displayed as evidence of their prowess. Natives hunt brown bear as they emerge from their dens in the spring for meat to be shared. The skins are left at the kill site pointed in a particular direction that carries spiritual meaning and no mention is made of the hunt lest the bears overhear the conversation. Bear hunting clearly means different things to these two cultures.

Difficult issues remain on the table. Rural re-determination is particularly controversial because, not unlike congressional redistricting, it draws lines on a map around urban areas demarcating populations that are not eligible for subsistence use rights and can harvest fish and game only within normal seasons and established limits of the kind that most Americans find familiar, even if they are a Native and even if their great-grandfather practiced subsistence hunting or fishing. Meanwhile, their next-door neighbor on the rural side of the line who moved to Alaska last year to take a white-collar job has subsistence rights and is allowed, for example, to catch 30 halibut per day and sell $400 of this catch per year. With many rural Alaskans maintaining post office box addresses in town, and with many urban recreational hunters and anglers looking for loopholes, determining the identity of those with and without subsistence rights is an ongoing headache for state and federal personnel.

On Prince of Wales Island, the largest and by far the most ecologically productive island in the Tongass National Forest of the southeast Alaskan archipelago, the harvesting of timber occurs at an economic loss due to high transportation costs and other factors. With recreation and tourism on the rise, the potentially negative effect of clear-cutting on scenic and ecological values adds to the argument against cutting. But it’s not that simple.

Tlingit interests on Prince of Wales Island claim that recreational hunters are allowed too large a harvest of black-tailed deer, thereby undermining their most important source of subsistence and their priority rights under ANILCA. Most deer are taken by hunters along logging roads, not only because of the greater access but because old -growth forest is poor deer habitat while timber lands recovering from harvests that took place in the last 30 years make ideal habitat because of the diversity of leafy, woody plants growing at a height that deer can reach. Coordinating forest cutting with deer habitat requirements, and thus subsistence needs and recreational hunting demands, not to mention employment and revenue considerations, therefore represents a challenge for managing timber and wildlife resources jointly and sustainably. Moreover, few reliable data are available on basic characteristics of the ecosystems being managed, such as how many deer there are, how many deer are harvested for subsistence and by recreational hunters, and how large a proportion of the Tlingit diet consists of venison.

This political ecological analysis of consumptive wildlife use rights in Alaska helps to illustrate principles of natural resource sustainability. When consumptive use of specific wildlife species is open-access, and when the food, fur, or other products are sold in global markets, depletion and collapse are the likely result. While an improvement over the tragedy of open access, maximum sustainable yield (see Chapter 7) enforced through regulations can also fail because it results in standing stocks less than half of natural levels with cascading ecological effects and because ecosystems exhibit chaotic and unpredictable variations in fish and wildlife populations, making it impossible to identify the sustainable yield beforehand.

The Alaskan economy remains heavily dependent on natural resources, though with a shift from consumptive harvesting of timber and fish to less consumptive ecotourism. Who will ultimately benefit from this new economy is still being determined.

Getting Started on the Sustainable Development Path

Jeffrey Sachs is a development economist at the Earth Institute at Columbia University rather than a political ecologist, but I am including a discussion of his excellent and inspiring 2005 book The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time in this chapter, partly as an antidote. Political ecology can be very insightful in diagnosing problems as we have seen, especially of environmental injustice and inequality in access to natural resources, but it is perhaps less skilled at identifying solutions. Sachs also uses the medical metaphor of “diagnosis,” but fortunately, he also provides prescriptions for a cure of many problems of natural resource degradation and poverty in the global economic periphery.

Like the human body, a society, part of which we can think of as an economy, is a complex system where different components are dependent upon one another. Your digestive, nervous, circulatory, immune, and skeletal systems, for example, can only function if the other systems are also functioning. Similarly, agriculture, water supplies, transportation, health care, education, and so forth are interdependent systems in a community. Just as the symptom of a fever can be caused by many different ailments, so poverty is a symptom that requires a differential diagnosis. In medicine, one must treat a patient in the context of their family and home environment. Similarly, poverty or prosperity rarely occurs in one person, or even in one household; it is a characteristic of an entire community. In medicine, the doctor must frequently monitor the patient’s condition, such as their temperature, cholesterol, or blood sugar levels. Similarly, monitoring and evaluation are critical in staying on the pathway of sustainable development. Did the new road really open up urban or even international markets for local farmers? Is the distribution of pesticide-laden bed nets really decreasing cases of malaria? How much have crop yields increased due to new fertilizers? Are people actually drinking the cleaner water from the new tube wells or are there unforeseen social barriers to using it? Each locality is poor for a different reason, and each requires a different remedy. Each is also at a different level on the ladder of development and needs a different treatment to climb the next rung.

As we saw in the case of land degradation, poverty lays at the heart of a number of land-use-based natural resources problems. These can become part of the poverty trap, alongside high rates of disease and child mortality, consequent rapid population growth (remember descendant insurance from Chapter 5), climatic fluctuations such as drought, and a loss of revenue when a single key natural resource export loses its market.

Poverty is often localized where basic infrastructures like roads, water and sanitation, electrical power, and telecommunications are lacking. It can occur in very densely populated urban slums, densely populated fertile valleys and plains, or in sparsely populated grazing regions where it is prohibitively expensive to provide infrastructure and connectivity. This kind of rural isolation is especially evident in Africa, where a dispersed population lacks a spatial node such as a port city from which economic development derived from foreign direct investment can spread. Here the problem is that globalization has thus far passed it by.

Disease ecology is also a critical factor in the poverty trap. While you have likely heard a great deal about how AIDS (Acquired Immuno- Deficiency Syndrome) is most virulent in Africa, malaria, a debilitating fever spread by mosquitoes, is at least as great a threat to human life.

Sachs is a tireless advocate of foreign aid. His argument is that, properly allocated, it can be an investment that sets a locality on a pathway of sustainable development. So what should aid be spent on? Sachs argues that there are four key investments that can break the vicious cycle of poverty if carefully allocated as a package:

- agricultural productivity focused on high-yielding seeds, irrigation water, and fertilizer inputs;

- basic health care, including family planning and combating environmental diseases like malaria and water-borne pathogens;

- education with an emphasis on universal primary education;

- and basic infrastructure such as water and sanitation, roads, electricity, and telecommunications.

The purpose of these investments is to meet the Millennium Development Goals established by the United Nations:

- Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger by halving the proportion of people living on less than a dollar a day and suffering from hunger.

- Achieve universal primary education.

- Promote gender equity and empower women.

- Reduce child mortality by two-thirds.

- Reduce maternal mortality by three-quarters.

- Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases.

- Ensure environmental sustainability, including halving the proportion of people lacking access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation.

- Develop a global partnership for development.

It is particularly encouraging to witness the recent increase in global efforts to shrink the malaria map. Since 1946, malaria has been essentially eliminated from the U.S., Europe, southern Brazil, northern China, and North Africa, but it remains pandemic in many tropical areas. It is especially virulent in tropical Africa where 90 percent of world cases occur—over 200 million per year, resulting in over 400,000 deaths, 70 percent of which are in children under five years old. With economic costs of at least $12 billion per year, it is one of the primary factors holding back sustainable development in Africa. A number of international efforts—including the Roll Back Malaria campaign, the Gates Foundation, and the President’s Malaria Initiative begun in 2005—are focusing on the free distribution of long-lasting insecticidal bed nets, antimalarial drugs such as artemisinin to replace chloroquine, and research toward a vaccine, where substantial progress was made in 2013. There is reason to be optimistic that the malaria map is about to be rolled back. Nevertheless, global commitments to meet the Millennium Development Goals continue to lag far behind the needs.

In contrast to many political ecologists, however, Sachs contends that globalization and trade has greatly reduced poverty and thereby has advanced the Millennium Development Goals, especially in regions like eastern China and urban India where it has been most active. What the low-income periphery countries of sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia lack is the foreign direct investment that globalization brings.

On this question of globalization and sustainable development, I find myself siding with Sachs. What is needed is a more progressive approach to globalization where poverty is ameliorated directly through targeted foreign aid rather than only as a side-effect of capitalist economic development, as powerful as that force can sometimes be for human progress. What is needed is a globalization where environmental and labor standards are actively advanced by organizations such as the World Trade Organization. In this manner, the 21st Century may see natural resources sustainability and the end of poverty achieved simultaneously—partly because each depends on the other.

Conclusion

In contrast to the neoclassical, ecological, and institutional schools of economics, political ecology focuses on diagnosing the political roots of environmental injustice and unequal distribution of the benefits of natural resources. While applicable to the U.S. and other developed countries, its particular focus is the problems of poverty and degradation of land-based resources in the world economic periphery. Managing natural resources for environmental sustainability is necessary but not sufficient. They must also be managed for the sustainability of human capital by meeting the basic needs for food, water, energy, and health of all humans.

With our quadfocals now placed securely on our noses, we are ready to proceed into a resource-by-resource analysis of sustainability in the management of land, water, minerals, and energy in Part III of this text.

Further Reading

Blaikie, P.A. and H. Brookfield, 1987. Land Degradation and Society. Methuen Books.

Sachs, J. 2005. The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for our Time. Penguin Books: London.

Media Attributions |

|