Unit 6: Evaluating Music

13 What is Good Music?

Esther M. Morgan-Ellis and David R. Peoples

It seems as if one of the objectives of this book should be to reveal what the difference is between “good” music and “bad” music. However, if you have read this entire book and still have no idea, don’t worry—the authors don’t know either. Or, at least, we are not able to make any generalizations about what is good and what is not, even if we are adept at identifying quality in specific instances. This is because music is so diverse in its forms and objectives that there cannot be a single standard of quality. When we ask, “Is this music good?,” what are we asking? Although this particular question is vague and unhelpful, asking questions can help us to judge the quality of a specific composition or performance.

First, we should think about the purpose behind a given composition. Is it supposed to make people dance? Is it supposed to provoke an emotional reaction? Is it supposed to make listeners feel patriotic? Is it supposed to incite rebellion? Is it supposed to be intellectually engaging? Then we should ask the question, “Is this piece of music successful at achieving its objective?” This way we can avoid pointless comparisons between pieces of music that serve completely different functions. There is no value in saying that a symphony by Beethoven is “better” than an Appalachian fiddle tune.

Second, we can measure a composition against others of its type. While it is misguided to compare a Bach cantata to a hip-hop track, we can argue that Bach wrote better cantatas than other 18th-century German church composers, or that Ice-T is a better rapper than Vanilla Ice. To do so, we need to agree on some specific criteria used to determine quality. This is very difficult. Most classical musicians agree that Bach is the greatest composer of his era, if not of all time. They will argue that his music is better than that of his contemporaries because it is more complex, or more expressive. But who decided that complexity and expressivity were desirable qualities? Bach was not highly regarded in his own time, when listeners preferred a more restrained approach to composition. Should that matter to us today? There’s a further problem. Although Bach’s music was not widely studied or performed until eighty years after his death, it now forms the bedrock of the classical music industry and educational system. Can those of us who grew up playing and listening to Bach’s music judge its quality, when that same music has been used to define and teach “goodness” in classical music? Or are we only able to judge less familiar composers in comparison to Bach?

Third, we might compare a piece of music to others of its kind by considering originality. When we find a pop song or a string quartet or a gamelan composition that we really love, we are probably attracted to it because, while representative of its type, it is somehow different in an appealing way. All songs played on Top 40 radio have a great deal in common, but a “good” song is likely to have something special that sets it apart from the others. All string quartets composed in the 18th century will share formal and stylistic features, but a “good” one will stand out as unique. What it means to be original and how innovations might be received will depend on the type of music.

Fourth, we can consider the skill of the composer or performer. Certain types of music—four-voice fugues, for example—are objectively difficult to craft, and we can empirically judge their quality. However, this is often not the case, as this type of evaluation requires strict criteria. We can also judge the skill with which music is performed. In the classical tradition, we tend to separate the quality of a performance from the quality of the music being performed. In other traditions, however, such is often not the case. The music of John Coltrane is “good” not because he wrote exceptional tunes but because his recordings are extraordinary. If he had spent his career publishing printed music, no-one would have noticed. Because he worked with a team of highly-skilled musicians to record and release groundbreaking performances, however, we hold his music in high esteem. And how do we know that his recordings are “good”? This again requires some level of agreement between members of the jazz community concerning the goals of their music.

Finally, we can take into account the impact that music has on listeners and society. We can argue that “good” music is important to someone, or plays a role in the development of art or culture. It has certainly been argued that the music of Wagner is “good” because it heavily influenced the next generation of composers. It has also been argued that Wagner is a “good” composer because many people love his operas. However, influence and popularity are often determined by factors that are independent of the music itself. Wagner happened to be a German male (which allowed him to be taken seriously) with a royal patron (which allowed him to focus on his work and to stage lavish productions of his most ambitious operas). These circumstances contributed significantly to his legacy. If Wagner had written all of the same operas, but they had never been staged and were forgotten today, would those operas still be “good”? Were there other composers writing at the same time who, due to less fortunate circumstances, have been forgotten, but who’s music was just as “good” or “better”? Is it even possible to know? To turn to another example, young people are often criticized for listening to “bad” (that is, popular and ephemeral) music. This has been going on for many generations, but no amount of criticism can stop anyone from listening to music that they love and that has meaning for them. Does the fact that a piece of music is important to someone make it “good”?

As these questions reveal, it is no easy task to determine whether a piece of music is “good” or not. It is tempting to paraphrase the words of Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, who famously declined to define pornography in a 1964 decision but instead stated “I know it when I see it.” Many of us would like to say of good music, “I know it when I hear it”—and sometimes we do. However, we should never forget the limitations of our individual perspectives, and we should keep our ears open to all of the good music that is waiting to be discovered.

The Pulitzer Prize

Despite the problems inherent in trying to identify the “best” music, we have long insisted on doing so. This is evidenced by countless competitions and awards across all genres of music. Perhaps the most prominent award given to a composer of art music is the Pulitzer Prize for Music, which has been awarded annually since 1943. The current criteria indicate that this award is “For a distinguished musical composition by an American that has had its first performance or recording in the United States during the year.” The history of Pulitzer Prize winners, therefore, should be a history of the best music composed in the last 75 years. In truth, of course, many of the composers and works to receive the Pulitzer have been forgotten, while many great musicians were never considered because their music was not considered to be art.

1945 Pulitzer Prize: Aaron Copland, Appalachian Spring

Of all the compositions ever to win the Pulitzer Prize, none may have been so warmly embraced by the listening public as Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring. This orchestral work—first conceived of as a ballet, but more frequently performed on the concert stage—has never left the repertoire, and it is regularly performed in versions for both chamber orchestra and full orchestra. Appalachian Spring also helped to solidify Copland’s reputation as a composer of explicitly “American” music. Indeed, Copland-esque soundtracks have been used to accompany on-screen cowboys and ranchers ever since the 1940s, and we have long accepted that the sound of Copland is the sound of rural America.

Copland’s Career

Aaron Copland (1900-1990) did not start off his career writing folksy-sounding concert pieces. His earliest interest lay in synthesizing jazz and classical idioms, as we saw George Gershwin do with his 1924 Rhapsody in Blue. Copland, however, did not meet with Gershwin’s success. Gershwin was an uneducated popular song composer who rose to the challenge of writing a sophisticated concert work and was therefore lauded for his accomplishments. Copland, on the other hand, had the benefit of a rigorous education, and in 1924 was concluding three years of study in Paris with the most renowned composition teacher of the 20th century, Nadia Boulanger. When he incorporated jazz into his early works, therefore, he was scorned by highbrow critics who thought that by doing so Copland was degrading his art. Copland gave up the project and instead wrote sophisticated concert music in a modern style for the rest of the 1920s.

The Great Depression convinced many composers of art music to adopt a more commercial style. They did so both out of necessity and for ideological reasons. It was not practical to write elite music for small audiences during a period of such hardship, but it also seemed unethical. What was the purpose of art if not to comfort people in their time of suffering? Copland was also interested in using music to further left-wing political causes in which he had taken an interest. He was particularly influenced by the rising interest among young progressives in American folk music, which was understood to represent the common people and their struggles.

Folk tunes had a major impact on Copland as he began to develop his unique musical language. All three of the ballets that cemented his reputation as a composer used folk melodies to portray rural America. Billy the Kid (1938) combines a variety of cowboy songs with Mexican folk music to tell the story of the famous outlaw. Rodeo (1942), also set on the Western frontier, features an Appalachian fiddle tune called “Bonaparte’s Retreat” in its final scene. And Appalachian Spring (1944) contains a set of variations on the Shaker hymn tune “Simple Gifts.”

Appalachian Spring

Before looking inside Appalachian Spring, however, we need to know a little more about how this ballet came to be. In 1942, Copland was commissioned to write a ballet “on an American theme” by dancer Martha Graham and music patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge. Copland completed the 25-minute score without a narrative in mind—his aim was simply to write music that sounded “American” and contained dramatic contrasts. In fact, he had no idea what the ballet was to be about until he saw it just a few days before the October 1944 premiere at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. He later loved to talk about the compliments he received from listeners who felt that he had perfectly captured the Appalachian mountains in music, when in fact no such idea had been in his mind while composing.

The dramatic narrative, which was developed by Graham after she heard the music, concerns the marriage of a young farming couple. The eight brief scenes portray the community coming together to celebrate the wedding, the various emotions felt by the bride and groom, and the adventure of embarking upon married life. The title, which replaced Copland’s working title, Ballet for Martha, was drawn from a line of Hart Crane’s 1930 poem “The Dance.”

Scene One

We will take a look at the first, second, and seventh scenes to get an idea about how Copland created “American”-sounding music. After seeing the ballet performed, he wrote his own summaries of the music and action incorporated into each scene. To describe scene one, he wrote “Very slowly. Introduction of the characters, one by one, in a suffused light.” In this excerpt, we can hear several of the techniques that characterize Copland’s music. He creates the impression of a wide open space by juxtaposing high and low sounds. He captures a sense of stillness by writing music that moves slowly and seldom changes harmony. Finally, his melodies outline triads in different key areas. This means that scene one is not in any particular key, and is therefore polytonal. But the music is not jarring or uncomfortable, like that which we heard in The Rite of Spring. Instead, Copland creates a floating effect: we often don’t know where we are or where we are going, but the experience is pleasant.

Scene One from Appalachian Spring

Composer: Aaron Copland

Performance: Harmonie Ensemble/New York, conducted by Steven Richman (2004)

Scene Two

The mood suddenly changes with scene two, which Copland described as follows: “Fast/Allegro. Sudden burst of unison strings in A major arpeggios starts the action. A sentiment both elated and religious gives the keynote to this scene.” Copland continues to employ polytonality, but we are now dancing instead of floating. He introduces a variety of exciting rhythmic elements, including mixed meter, that make it difficult (or even impossible) to tap your foot along to the music. The elated sentiment that Copland describes is communicated by means of fast tempos and disjunct melodies that include large leaps. The religious sentiment is communicated through a sequence of powerful, emotive harmonies.

Scene Two from Appalachian Spring

Composer: Aaron Copland

Performance: Harmonie Ensemble/New York, conducted by Steven Richman (2004)

Scene Seven

Copland’s use of a traditional tune comes in scene seven:

Calm and flowing/Doppio Movimento. Scenes of daily activity for the Bride and her Farmer husband. There are five variations on a Shaker theme. The theme, sung by a solo clarinet, was taken from a collection of Shaker melodies compiled by Edward D. Andrews, and published under the title “The Gift to Be Simple.” The melody borrowed and used almost literally is called “Simple Gifts.”

Scene Seven from Appalachian Spring

Composer: Aaron Copland

Performance: Harmonie Ensemble/New York, conducted by Steven Richman (2004)

Copland regularly relied on the work of scholars and song collectors. In this case, he turned to Dr. Andrews’s 1940 volume The Gift to Be Simple: Songs, Dances and Rituals of the American Shakers for source material. Copland first presents the hymn tune in the solo clarinet. Like Bartók (see Chapter 9), he does not alter the melody at all, but he does provide an original and very modern harmonization. Copland then leads the listener through a series of variations, each of which is more rhythmically exciting and virtuosic than the last.

It is interesting to note that Copland was in fact one of the early champions of music appreciation as a subject of study. He sought to reveal the secrets of the concert hall to as many new listeners as possible, and he dedicated much of his time to talking and writing about music for the public. His 1937 volume What To Listen For In Music is an early classic of the music appreciation literature and is still in print.

1965 Pulitzer Prize: The Duke Ellington Controversy

After Copland, the Pulitzer Prize was awarded to a long list of highly-educated white male composers writing in the European concert tradition. Clearly, jury members considered the production of “good music” to be linked to genre, race, and class. The winning works included symphonies, concertos, cantatas, and operas. However, the 1960s saw growing unease among listeners, performers, and scholars with this narrow definition of what could be “good” in music. Jazz, in particular, had developed into a sophisticated concert genre, and a number of composers were producing music that was, by many measures, just as “good” as that coming out of the classical sphere. The primary differences lay in instrumentation (jazz band instead of orchestra), harmonic language (jazz composers used different scales and chords), and the incorporation of improvisation.

This tension came to the forefront in 1965. Upon considering the various nominated works, the Pulitzer jury concluded that none of them was worthy of the prize. Instead, they recommended that a special citation be granted to Duke Ellington (1899-1974) in recognition of his lifetime of accomplishment in the field of music. Ellington had initially been nominated by Viola Lomoe, the wife of a newspaper editor and a dedicated fan of jazz. She had suggested that the jury consider Ellington’s recent The Far East Suite, which she described as “being one of the larger forms of orchestral music” and therefore eligible for recognition. However, she also suggested that Ellington’s entire career was prize worthy. “If the whole body of Ellington work can be considered,” she wrote, “that can be heard anywhere, any time. In fact, it’s inescapable, though often it’s played or sung without a credit line.”

Ellington’s Career

Lomoe made a valid point about the ubiquity of Ellington’s music, which has become ingrained in American culture. He composed over 3,000 popular songs in his lifetime, the best-known of which is perhaps “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)” (1931). Ellington first rose to national prominence as a pianist and band leader in 1927, when his group became the house band at the Cotton Club in Harlem. The Cotton Club was one of several 1920s-era establishments that catered to white New Yorkers who were attracted by the perceived danger and excitement of dabbling in African American culture. While the club only admitted white patrons, the musicians, dancers, and servers were all black. Patrons and employees were not permitted to mix, however, and the advertising and decorations established the Cotton Club as a place where white New Yorkers could safely encounter the exotic black other. Although Ellington and his musicians were sometimes required to play up to stereotypes, they were still able to create masterpieces in the jazz idiom, and their music was heard across the country via regular radio broadcasts.

For several decades after leaving the Cotton Club in 1931, Ellington and his band toured internationally and made popular recordings. Ellington always thought of his music as art, and he resisted the jazz label, instead describing his own creations as “beyond category.” While his songs gained the greatest popularity, many of his compositions relied on the extended forms of classical music.

The Far East Suite

The Far East Suite, recorded in 1966, is one such work. It contains nine movements, ranging from two-and-a-half to eleven-and-a-half minutes in length, and was inspired by world tours undertaken by Ellington’s group in 1963 and 1964. The suite was a collaboration between Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, his longtime creative partner. While cowriting is common in jazz, the fact that The Far East Suite had two composers sets it apart from the classical tradition, in which instrumental compositions are always the work of an individual.

Each selection on the album represents Ellington’s impressions upon visiting a foreign country. Commenting on the trip, Ellington stated, “The cats in the band go crazy about everything they see.” In essence, each piece took a geographic area as an artistic starting point, resulting in continuous contrast and the ongoing transformation of accompanimental ideas. The Far East Suite includes an array of constantly evolving interactions between soloists (whether improvising or not) and unique combinations from within the ensemble.

A feature of Ellington’s compositions is the thoughtful use of each instrument’s unique voice. In the suite, each of the instrumental voices conjures up an element of the travel experience. The first movement of the suite, entitled “Tourist Point of View,” sets the mood by contrasting comforting and disorienting sounds. In the introduction, we hear dissonant chords played by the brass. Upon the entrance of the saxophone soloist, these are replaced by bright, high harmonies in the winds, which in turn give way to a call-and-response texture that pits the two sections against one another. The constant changes in texture and timbre suggest an onslaught of new and unfamiliar experiences. In the foreground, we hear smooth solos that use intervals similar to those in Eastern melodies, although the airy sound of the tenor saxophone serves as a touchstone of familiarity. The energy reaches a peak with Cat Anderson’s high trumpet playing, but the track concludes with a general decrescendo until finally the bass and drums fade out.

“Tourist Point of View” from The Far East Suite

Composer: Duke Ellington

Performance: Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra (1967)

As the suite progresses, each movement takes on a new story, which is illustrated using a combination of unique musical elements. These range from the use of a clarinet in “Bluebird of Delhi” to portray the song of a bird, pitted against against a swinging ensemble (typical of Ellington/Strayhorn’s sound), to the muted brass improvisations in “Amad,” which suggest the Muslim call to prayer against a persistent piano ostinato.

“Isfahan” (a city in Iran) is captured with a slow jazz ballad that showcases the sound of Johnny Hodges on alto saxophone against a relaxed and relatively soft ensemble. This movement has an easygoing atmosphere. Dramatic harmonies, produced by winds and muted brass, are paired with heavy rhythmic punctuations and ostinatos. Gravity is provided by occasional full ensemble interjections, some of which are echoed by unaccompanied melodies in the saxophone. (“Isfahan” is still popular among jazz artists today and is regularly performed by ensembles of varying size).

“Isfahan” from The Far East Suite

Composer: Duke Ellington

Performance: Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra (1967)

We hear the influence of music from the 1960s in the rock inflections (especially in the drums) and non-swung beat divisions of “Blue Pepper.” But the suite quickly mellows in “Agra,” and concludes with what might be described as a sequence of cadenzas in the final movement, “Ad Lib on Nippon.” The Far East Suite took elements that had developed over the course of a decades-long collaboration between the artists Strayhorn and Ellington—in particular, the use of slowly-shifting ensemble colors that interacted with and influenced solo improvisations—to a new level, illustrating a story shaped by personal experience.

Disappointment

However, 1965 is not remembered as the first year in which a jazz composer was recognized with a Pulitzer Prize. This is because, despite the jury’s recommendation, the Pulitzer board refused to issue a special citation to Duke Ellington. Two jurors resigned in protest, and many more felt that a serious injustice had been perpetrated. The Pulitzer Prize was meant to recognize excellence in American music. Jazz was, without question, the most significant musical art form to have emerged in the United States, and Ellington was one of its most prominent and creative figures. If the purpose of the Pulitzer Prize was to celebrate excellence in American music, on what grounds was Ellington to be denied recognition? The man himself joked, “Fate is being kind to me. Fate doesn’t want me to be famous too young.” (He was 66 years old.) However, Ellington was offended—not because the board had rejected him, but because they had rejected a form of music that he valued highly. “Most Americans still take it for granted that European music—classical music, if you will—is the only really respectable kind,” he later said in an interview. “By and large, then as now, jazz was like the kind of man you wouldn’t want your daughter to associate with.” Ellington firmly believed that jazz could constitute “good music” and that criteria could be established by which the determine quality in jazz.

1997 Pulitzer Prize: Wynton Marsalis, Blood on the Fields

Despite the uproar, it was still to be several decades before a jazz composer would win the Pulitzer Prize for Music. By the 1990s, it was well established that the Pulitzer in music usually went to compositions for symphony orchestra. Occasionally, small chamber ensembles, choirs, and even solo piano were selected. Only once had the award gone to an electronic composition: Mario Davidovsky’s Synchronisms No. 6 for Piano and Electronic Sound (1970). It comes as no surprise that many musicians detected a sense of exclusiveness and prejudice on behalf of the Pulitzer committee.

In 1994, notable composer and performer Gunther Schuller (who had performed with jazz musicians Dizzy Gillepsie and John Lewis) was awarded the Pulitzer for his Of Reminiscences and Reflections, a composition for large orchestra. Although Schuller was a member of the jazz community, his winning composition contained few jazz elements. In particular, it lacked a jazz sound and performance style. As a result of his win, however, Schuller was invited to adjudicate for the 1997 Pulitzer in Music. The other jury members included a jazz critic, a jazz performer, and two traditional composers. With a majority of jury members having extensive experience in jazz, the panel finally chose to award the Pulitzer to a jazz musician.

Developing Blood on the Fields

Several years earlier, the Lincoln Center had commissioned jazz artist Wynton Marsalis (b. 1961) to present a new composition. The 32-year-old Marsalis was already well known as a jazz trumpeter and composer; indeed, he had established the Lincoln Center’s own summer jazz series in 1987, and had made great progress in his mission to institutionalize jazz as a respected American art form. Although Marsalis grew up in New Orleans and interacted with important jazz musicians from a young age, most of his early training was in classical music, and it was with the intent of pursuing an orchestral career that he enrolled in the Juilliard School in 1979. Although he soon decided that his future lay in jazz, Marsalis’s background prepared him to create music that drew from a diversity of traditions, styles, and forms. In response to the Lincoln Center commission, therefore, he decided to create a work in the European oratorio tradition. Oratorios employ an orchestra and vocal soloists to tell a story, although their presentation does not incorporate costumes, sets, or acting. Instead, the story is communicated entirely through sound.

For his oratorio, which was premiered in 1994, Marsalis crafted a narrative that related the experiences of an enslaved couple. His story begins on a slave ship and ends with the protagonists striking out for the north and freedom. The two main characters are Leona and Jesse, the latter of whom was a prince before his enslavement. Over the course of Blood on the Fields, the two aid each other in adjusting to their new lives, finding hope for the future, and eventually escaping from bondage. Originally, Marsalis had intended Blood on the Fields to be “tragic the whole way through, with no redemption.” Following extensive study and reflection, however, he concluded that optimism was “a very important part of the jazz expression.” Marsalis’s attitude—as well as his music—was deeply influenced by Duke Ellington, whose work he perceived as being essentially optimistic.

In creating the music for Blood on the Fields, Marsalis drew from a variety of African American traditions, including New Orleans jazz, blues, funk, chants, field hollers, work songs, and spirituals. He wrote for a jazz orchestra of forty musicians, with an important role for himself on the trumpet. In addition to playing their instruments, the orchestra members also recite text in unison to prepare each scene. Marsalis patterned this approach on the tradition of ancient Greek theater, which employed a chorus to narrate and reflect upon events.

Work Song (Blood on the Fields)

We will consider “Work Song (Blood on the Fields),” which is the sixth scene of the oratorio’s twenty-one. In this scene, Leona and Jesse are working in the fields, and they describe their monotonous labor and lament their unbearable situation. Although the scene follows quickly upon that in which they are purchased at auction, we are informed that in fact fourteen years have passed.

“Work Song (Blood on the Fields)” from Blood on the Fields

Composer: Wynton Marsalis

Performance: The Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra (1997)

The first thing we hear is Marsalis’s trumpet. The growling sound he produces using a plunger mute is modelled on the playing of James “Bubber” Miley, who pioneered this style as a member of Ellington’s band in the 1920s. Marsalis’s improvisatory melody imitates the shapes and sounds of blues singing, although of course his playing communicates emotion without the benefit of words. In between his phrases, the members of the orchestra recite in unison.

Soon, the members of the orchestra establish a groove, which remains fairly consistent for the remainder of the scene. Throughout Blood on the Fields, Marsalis makes an effort to represent the motions and elements of each scene in music. In this case, we hear the regular rhythms of field labor. Punctuated brass exclamations and forceful drum hits emphasize the heaviness and effort of the work, while the unevenness of the rhythmic pattern suggests strain and sudden movements. The groove itself is rooted in the practices of various African and African-derived musical traditions. The process by which many distinct instruments each contribute a fragment to a complex musical whole is known as hocket, and is characteristic of black musical styles ranging from jali recitation to funk.

The regular interjections of other instruments suggest the sound and texture of New Orleans jazz, in which no single instrument carries the melody. Instead, each member of the ensemble contributes a distinct line to the texture, all of which combine to produce a rhythmic cacophony. In the case of “Work Song,” we might also hear the instruments as the voices of other enslaved workers, joining the two vocalists in protest.

2013 Pulitzer Prize: Caroline Shaw, Partita for 8 Voices

The 2013 Pulitzer Prize attracted an unusual amount of attention. To begin with, at 30 years old, Caroline Shaw (b. 1982) was the youngest composer ever to win a Pulitzer. In addition to that, she was only the fifth woman to win in the seventy years of the competition. (Ellen Taaffe Zwilich was the first, in 1983.) Finally, the work itself was out of the ordinary. Partita requires amplified singers to employ unusual and non-Western vocal techniques, and at the time of the award only one vocal ensemble—Roomful of Teeth, of which Shaw herself is a founding member—had ever performed it. In fact, Roomful of Teeth had not even premiered the complete work, but had programmed individual movements as they were completed. Partita had also not been published and could only be heard on Roomful of Teeth’s eponymous 2012 album, which itself won a Grammy for Best Chamber Music/Small Ensemble Performance in 2013. In this way, Partita was more like a pop song than a classical composition. As a result, it inspired discussion not only about whether or not it was “good” but about whether it even had the necessary characteristics to satisfy the criteria used to evaluate compositional quality.

Roomful of Teeth

We can’t understand Partita without understanding the history and mission of Roomful of Teeth. The group was founded in 2009 by Brad Wells, who had a vision for an eight-part vocal ensemble that would break new ground in the world of art music. Most choirs adopt a uniform vocal production technique derived from the European tradition. However, the human voice is capable of producing an extraordinary range of sounds, and there is boundless variety in the techniques used by non-Western and popular singers. The members of Roomful of Teeth learn these techniques from world-renowned experts. In the past decade, the group has studied Tuvan throat singing, yodeling, Broadway belting, Inuit throat singing, Korean P’ansori, Georgian singing, Sardinian cantu a tenore, Hindustani music, Persian classical singing, and Death Metal singing. All of these techniques have been incorporated into their performances. To accomplish this, Wells commissions composers to write music expressly for the group. Much of this work takes place during an annual gathering at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) in North Adams, Massachusetts, where teachers, singers, and composers come together to create new music.

As you can imagine, not just any choir can sing the repertoire that is created for Roomful of Teeth. Although the music is notated, the techniques required to perform it are highly specialized, and any vocal ensemble that wants to take on the challenge will require training. For this reason, few other choirs have ever performed Partita. Roomful of Teeth, on the other hand, continues to perform the work regularly. Some of their concerts are traditional in format, but they also engage with experimental performance techniques. In January of 2019, for example, they performed Partita outdoors in Times Square to the accompaniment of the LEIMAY Ensemble, a contemporary dance troupe.

Shaw and her Inspirations

Caroline Shaw (b. 1982) was among the first composers to write for Roomful of Teeth. Her training at the time she began work on Partita, however, was oriented towards violin performance, not composition (or even vocal performance). She only entered a PhD program in composition in 2010. This also makes her unusual. Most previous Pulitzer winners were established figures with degrees, university positions, and long lists of major works. Shaw was essentially unknown.

The inspiration for Partita came from several sources. The first was Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing 305, which can be viewed at the MASS MoCA, where Roomful of Teeth completes an annual residency. Wall Drawing 305 is not a work of visual art in the traditional sense (just as Shaw’s Partita is not a traditional choir piece), and might be categorized as conceptual art. The “work” is, in fact, a set of instructions intended to guide draftsmen in placing one hundred points on a wall. These instructions can be followed by anyone in any space to create the drawing. LeWitt was interested in randomness, and he sought to prevent the emergence of patterns in the visual product. No two realizations of any work in his Wall Drawing series will be the same.

Shaw was attracted to LeWitt’s artistic vision, and she used several of his instructive texts in Partita. Her description of the work also ties it to Wall Drawing 305: “Partita is a simple piece. Born of a love of surface and structure, of the human voice, of dancing and tired ligaments, of music, and of our basic desire to draw a line from one point to another.” However, she also cites Times Square as a source for the work:

Since my very first years living in New York City, I have spent a lot of time in Times Square. I used to walk through the area right after I moved there just to take in its unique combination of chaos and magic. It is truly unlike any place in the world. I love to see how many people come to the city and visit Times Square, who are always looking up in awe and confusion and wonder. It is that mix of confusion and wonder that is also deeply in Partita. . . I also like to think about the traffic patterns that move through Times Square, intersecting, crossing, and pausing in different ways, just like the text in the first movement…

Finally, Shaw took the title and form of Partita from the tradition of Baroque dance suites. Bach used the terms partita and suite almost interchangeably, although his partitas are somewhat looser in form. Shaw would have encountered the term partita as a violinist, since that is how Bach labelled his suites for solo violin. Three of Shaw’s movements share the names of typical Baroque dances: “Allemande,” “Sarabande,” and “Courante.” The final movement, titled “Passacaglia,” links Partita with a different Baroque form, for a passacaglia is a set of variations over a repeating bass line. We do not find passacaglias in genuine Baroque dance suites.

Passacaglia

To get a sense of how Partita sounds, we will consider the last of the four movements, “Passacaglia.” The movement opens with the ensemble presenting a cycle of harmonies. They sing the same chord progression three times, but each time using a different vocal timbre. The first time through, they produce warm, rounded sounds. The second time, they shift timbres mid-pitch, switching from bright to subtle. The third time, they sing in a chest style derived from Bulgarian choral practice, producing a piercing and aggressive sound followed by a gasping sigh.

“Passacaglia” from Partita for 8 Voices

Composer: Caroline Shaw

Performance: Roomful of Teeth (2013)

Next we hear the chord progression again, but this time it is overlaid with oscillating figures in half of the voices. These carry into the subsequent section, providing the backdrop for a high melody sung in octaves and then for spoken text extracted from LeWitt’s Wall Drawing 305. During this passage we also hear harmonic overtone singing from the men, who manipulate low pedal tones to produce a rainbow of high-pitched sounds. One by one, the singers switch to reciting LeWitt’s text, until we are left with a cacophony of speaking voices. Isolated pitches extracted from the opening chord progression occasionally pierce the texture.

The cacophony is only resolved by the production of a grating sound derived from Korean pansori singing. This builds in strength before transforming into the opening chord, which inaugurates one final pass through the harmonic progression in chest voice. A second pass begins, but is derailed by the introduction of new chords. More overtone singing ornaments the final harmony of the piece.

2018 Pulitzer Prize: Kendrick Lamar, Damn.

The 1997 decision to grant the Pulitzer Prize to a jazz composer certainly broke new ground, but the 2018 decision represented an even bolder divorce with tradition. There were, as always, three finalists. The most conventional work under consideration was Michael Gilbertson’s Quartet, a work for string quartet in the concert tradition. The next contender was Ted Hearne’s Sound from the Bench. This cantata for chamber choir, two electric guitars, and drums is a bit less conventional. In it, Hearne combines text from landmark Supreme Court decisions with excerpts from ventriloquism textbooks to comment on the evolving legal notion of corporate personhood. Despite any eccentricities, Gilbertson and Hearne are both conservatory-educated composers who write concert works for traditional ensembles, and are therefore typical Pulitzer Prize contenders.

More Controversy

Neither Gilbertson nor Hearne won the competition, however. Instead, the jury awarded the Pulitzer Prize to Kendrick Lamar for his hip-hop album DAMN. In doing so, they rejected 75 years of received wisdom about what kind of music is prize-worthy, instead making the bold assertion that hip-hop has the potential to be “good” music and that there are criteria for judging the relative quality of hip-hop artists and tracks. How else could they identify Lamar as being the “best”? However, this effort to bring hip-hop into the world of the Pulitzers presented challenges. To begin with, DAMN. is not a literate musical work. That is to say, it did not begin life as notes on a page, and musical notation does not play a role in its preservation. This, of course, is true of most popular genres, and that leads us to the next point.

Up until 2018, only works in art music genres had been considered for the prize. Jazz, of course, was not always considered to be “art music,” but by the 1960s there was at least a strong argument being made that it ought to be, and it was possible to obtain a college degree in jazz studies. Furthermore, the specific Ellington work cited in 1965 was not a popular song, but rather an adventurous instrumental composition, while Marsalis’s 1997 composition was even more self-evidently a work of “art.” Jazz in general was not exactly popular by the time it was recognized with a Pulitzer, and the works in question were particularly cerebral. Hip-hop, on the other hand, is decidedly a popular genre.

Furthermore, Kendrick Lamar is decidedly a popular hip-hop artist. He is not a fringe figure, producing artsy, experimental tracks in the hip-hop vein for a small group of admirers. With scores of Grammy nominations, over a dozen Grammy wins, multiple million-selling albums, and a string of singles at the top of the Billboard Hot Rap charts, Lamar’s music is mainstream. In this respect, he was a new type of Pulitzer Prize winner. Before, the jury had often recognized artists who were well-known in the world of concert music, but it had never selected a winner who was genuinely popular. This raised questions not only about how “good” music can be identified but also about the purpose of the Pulitzer. In the past, it had served to boost the careers of little-known composers, or at least provided support to those creating music in a field that offered few opportunities for financial gain. Lamar needs neither fame nor money. What purpose could be served in providing him with more of both?

The answer, of course, is that the art music establishment—represented by the Pulitzer Prize jury—was seeking to make a statement about its own values. By extending the honor to Lamar, they both acknowledged the profound impact that hip-hop has had on art music composers and suggested that the categories of “art” and “popular” might not even make sense anymore. Good music is good music—so why should anyone get hung up on genre? The gap between the worlds of art and popular music still exists, of course. Nowhere is this more evident than in the awkward phrasing of the Prize jury’s citation, which describes DAMN. as “a virtuosic song collection unified by its vernacular authenticity and rhythmic dynamism that offers affecting vignettes capturing the complexity of modern African-American life.” This is not language that would speak to the average hip-hop fan. However, it does speak to classical music aficionados, and it positions DAMN. within the lineage of Pulitzer Prize-winning works.

DNA

The jury selected “DNA” as the emblematic track from the album, so we will consider that example. Most hip-hop is highly collaborative: Producers, rappers, and studio musicians work together to create individual tracks, each shaping the final product in different ways. There is seldom a single artist who decides exactly how it will sound. In the case of “DNA,” Lamar worked with Michael Len Williams II (b. 1989), a producer and rapper who has also collaborated with Gucci Mane, Miley Cyrus, Rihanna, and Beyoncé (he contributed to “Formation,” mentioned in Chapter 5). “DNA” grew out of a beat that Williams had originally prepared for Gucci Mane, but that he offered to Lamar while they were working on tracks that would eventually become part of DAMN. Lamar was inspired by Williams’s work and created the first part of “DNA.” In the recording studio, however, Lamar began rapping a capella, subsequently asking Williams to build a beat around his words.

“DNA”

Composers: Kendrick Lamar & Michael Len Williams II

Performance: Kendrick Lamar (2017)

The result is a single track in two distinct parts. At the midway point, the pulse breaks down. We hear an excerpt from a televised attack against Lamar, made by Geraldo Rivera on Fox News: “This is why I say that hip-hop has done more damage to young African Americans than racism in recent years.” Seemingly in response, Lamar’s rapping accelerates and the rhythms become staggeringly complex. Williams later stated that he “wanted it to sound like he’s battling the beat,” which it certainly does. The pulse recedes into the background during this section, encouraging the listener to focus entirely on the intense rhythmic exchanges between Lamar and his environment. The lyrics in “DNA” are wide-ranging, but they return repeatedly to issues of disenfranchisement and generational trauma in the black community. Lamar uses hip-hop to shine a light on these problems—mocking Rivera’s reactionary dismissal in the process.

Greatness and Genre

The preceding discussion about the Pulitzer Prize for Music has essentially been a discussion about “greatness” and genre. For most of the twentieth century, the Pulitzer committee restricted their concept of “greatness” to classical music. In the late twentieth century they expanded it to include jazz, and in the twenty-first century that have expanded still further to include hip-hop. What will come next? We can only wait and see. However, it is clear that the committee has historically perceived some genres as superior to others, and continues to see “greatness” only in specific realms.

Some of the best performing artists, however, clearly do not place these same limitations on music. In this section, we will explore the work of individual artists and performing ensembles that have excelled in the realm of classical music, but have put as much (or more) energy into other genres. All of these artists would disagree that any one musical genre is superior to another. Instead, they hear good music everywhere and are inspired by a variety of styles and approaches.

Alarm Will Sound

Alarm Will Sound is an instrumental ensemble based in New York City. The group was initially formed by students at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY. While pursuing degrees in music, founders Gavin Chuck and Alan Pierson got into conversation about the limited opportunities for the performance of New Music (a standard term for recent, often experimental, art music compositions, many of which might be classified as avant-garde)—and especially minimalist music. They recruited a group of interested performers and started a concert series. Upon graduating from Eastman, the members of the ensemble decided that they wanted to keep working together, and in 2001 Alarm Will Sound was founded.

The group’s first concert under their new name took place on May 24, 2001, in New York City’s Miller Theater. Unsurprisingly, given their collective interests, the program explored the music of minimalist composer Steve Reich (b. 1936). Reich was at the forefront of the development of minimalism in the 1960s. Although minimalist composers take a variety of approaches to their work, they share an interest in developing extended compositions from limited musical material. Reich himself has always detested the term “minimalism,” and the more descriptive “pattern and process music” is often used instead. This is fitting: Most minimalist composers employ fixed transformative processes in their work.

The group’s first concert under their new name took place on May 24, 2001, in New York City’s Miller Theater. Unsurprisingly, given their collective interests, the program explored the music of minimalist composer Steve Reich (b. 1936). Reich was at the forefront of the development of minimalism in the 1960s. Although minimalist composers take a variety of approaches to their work, they share an interest in developing extended compositions from limited musical material. Reich himself has always detested the term “minimalism,” and the more descriptive “pattern and process music” is often used instead. This is fitting: Most minimalist composers employ fixed transformative processes in their work.

Reich’s Compositional Processes

Reich’s earliest experiments were completed using tape loops. He discovered that if he played two identical loops of audio tape at slightly different speeds, he could produce a dazzling and constantly shifting array of effects, opening up a world of sound that could never be detected in the untransformed material. Reich’s first completed tape piece did not even use musical sounds. Instead, he built Come Out (1966) using a clip from an interview with Daniel Hamm, one of the Harlem Six—a group of black men (mostly teenagers) who were coerced into confessing to a 1964 murder and denied adequate representation by the courts. Although the men were convicted by an all-white jury in 1965, all but one of the charges were eventually overturned. In Come Out, we hear Hamm explaining the means to which he had to resort in order to convince police that he and his co-defendants had been beaten in jail and required medical attention.

Steve Reich created his pioneering tape loop composition Come Out in 1966.

Come Out was initially a byproduct of a sound collage that Reich built at the request of civil rights activist Truman Nelson, but it ended up being a broadly influential minimalist experiment. Over the course of the 13-minute work, Hamm’s voice slowly dissolves into a cacophony of rhythms and timbres. The words soon become unintelligible as the listener’s interest shifts to the element of pure sound. Although it is almost impossible to detect the gradual changes that are taking place, no two seconds of the recording are the same. Sustained attention is rewarded with an inimitable sonic experience.

Reich soon applied similar techniques to musical material, at the same time developing new approaches to facilitating gradual change over extended periods of time. Reich was a highly trained musician, having studied at the Juilliard School in New York City and Mills College in Oakland, CA. He also had omnivorous tastes: He was equally enthralled with jazz, the music of Bach and Vivaldi, rock, and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Later, he took opportunities to study non-Western traditions, including Balinese gamelan and West African drumming. All of these influenced his mature style.

Tehillim

On their inaugural concert, Alarm Will Sound performed two large-scale Reich works for orchestral ensemble and singers: Tehillim (1981) and The Desert Music (1983). We will consider Tehillim, which, by Reich’s own account, represented his first attempt to engage musically with his Jewish heritage. The texts, sung in Hebrew by four female voices, are taken from the Book of Psalms (the original Hebrew word for which is “Tehillim,” which literally means “praises”). In the first movement, we hear four lines from Psalm 19:

The heavens declare the glory of God;

the skies proclaim the work of his hands.

Day after day they pour forth speech;

night after night they reveal knowledge.

They have no speech, they use no words;

no sound is heard from them.

Yet their voice goes out into all the earth,

their words to the ends of the world.

In the heavens God has pitched a tent for the sun.

At first, a solo voice is accompanied only by a tambourine without jingles (intended by Reich to evoke the small drum mentioned in Psalm 150) and clapping—another mode of rhythmic accompaniment that was in use during Biblical times. We hear the entire Psalm text sung to a continuous melody, which is shaped by the rhythms of the Hebrew words. This is an atypical way for Reich to open a piece of music, but he soon begins applying transformations.

The second time through the melody, the singer is doubled by a clarinet, while a second percussive accompaniment of tambourine and clapping enters in canon with the first. Next, we hear the melody in a two-voice canon, one singer echoing the other. Soon after the canon begins, the strings enter with sustained harmonies. At the conclusion of this turn through the complete melody, the tempo slows and the texture fractures into a four-voice canon. The four singers repeat each individual line of the Psalm many times. They are doubled by electric organ, which contributes a reedy timbre, and accompanied by maracas. The sustained string harmonies gradually shift, seemingly out of time with the voices. Finally, the original soloist—again doubled by clarinet—assumes the melody once more, to the accompaniment of drums and maracas. She is briefly harmonized by one of the other singers, but the movement ends much as it began.

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | Melody | The Psalm text is presented by a solo singer and accompanied by tambourine and clapping. |

| 0’36” | Melody (repetition) | Another singer repeats the melody, which is now doubled by clarinet. |

| 1’12” | Canon in 2 voices | The two singers perform the melody in canon. |

| 1’47” | Canon in 2 voices (two repetitions) | The strings enter with sustained harmonies. |

| 2’59” | Canon in 4 voices | The tempo slows; each phrase is repeated many times; the voices are doubled by reed organ and accompanied by maracas; the string harmonies continue. |

| 8’49” | Melody | The solo singer is doubled by clarinet and accompanied by tambourine, clapping, and maracas. |

| 9’24” | Melody (repetition) | The string harmonies return. |

| 9’58” | Melody (repetition) | A second singer harmonizes below the melody. |

| 10’32” | Melody (final statement) | The texture thins as elements disappear one by one. |

While Tehillim is quite different from Come Out in all surface respects, we can see how Reich’s basic compositional process is consistent. The textures in Tehillim—as in Come Out—are created from the increasingly complex layering of limited sound material. In the case of Tehillim, Reich relies on rhythmic and melodic canons, augmented by slow-moving, kaleidoscopic harmonies.

Orchestrating Aphex Twin

The members of Alarm Will Sound were brought together by their love for music like Tehillim, and in their early years they found a great deal of success staging concerts that highlighted the work of individual living composers. However, they also shared a passion for popular music—in particular, the innovative electronic dance music of Aphex Twin. Members of the ensemble began discussing the possibility (and purpose) of recreating Aphex Twin’s music using acoustic instruments.

According to founder Gavin Chuck, the idea was controversial: “There were heated debates about the nature of digital vs. acoustic sound, and of machine precision vs. human expressiveness. There were disagreements about whether we should be as faithful as possible to the originals, or interpret them more openly.” Despite the varied opinions about the merit of such a project, Alarm Will Sound eventually took it on. Their work culminated in the 2005 album Acoustica, which primarily featured arrangements taken from Aphex Twin’s 2001 album Drukqs.

Whether or not all of the work required to make and record these arrangements was worthwhile is debatable. We will consider the opening track from Acoustica, “Cock/Ver10.” One might argue that Alarm Will Sound’s limited sound palette and acoustic means of production are inferior to the programmed beats, digitally-refined timbres, and studio effects of Aphex Twin’s original—or one might prefer the sounds of orchestral instruments. It is hard not to be impressed by the skill of the arranger, Stefan Freund, who translated Aphex Twin’s track into an orchestral score, and by the individual performers, who place complex rhythms and melodic gestures in exactly the right place.

“Cock/Ver10”

Composer: Aphex Twin (arr. Stefan Freund)

Performance: Alarm Will Sound (2011)

“Cock/Ver10” was included in Aphex Twin’s 2001 album Drukqs. This is the playlist for the entire album.

From Chuck’s perspective, the strength of the project lay in its capacity to connect the ensemble with new audiences and put their artistic values on display. It became, in his words, “an important platform from which to pursue a wide-ranging artistic vision that doesn’t worry too much about genre—electronic vs. acoustic, high-modernist vs. pop-influenced, conventional classical concert vs. multimedia experience.” In short, by recording the works of Aphex Twin, Alarm Will Sound proved that they were eager to embrace good music from unexpected quarters.

Yo-Yo Ma

Perhaps the most visible and influential individual to make a career as a classical crossover artist has been cellist Yo-Yo Ma. His work has embraced a range of folk and non-Western musical styles, with the result that he has successful bestowed his own cultural prestige on a large number of performers and traditions that might otherwise not have come into contact with the classical establishment. His projects have resulted in the creation of a lot of excellent music and the introduction of new sounds to classical audiences.

Classical Mastery

Yo-Yo Ma was born in Paris to Chinese parents, but his family immigrated to the United States when he was seven. He first gained prominence as a child prodigy. Almost immediately after his arrival in the States, Ma played for Presidents John F. Kennedy and Dwight D. Eisenhower at a Kennedy Center benefit concert that was broadcast on national television. This was the first in a series of prominent performances and television appearances that introduced Ma to the American public.

A young Yo-Yo Ma played cello on live television in 1962.

After earning his bachelor’s degree at Harvard University in 1976, Ma embarked on what could have been a typical concert career. He appeared as a soloist with orchestras around the world, collaborated with chamber musicians, and released these award-winning recordings offered Ma’s interpretation of the complete Bach cello suites—a rite of passage for any cellist who wants to be counted among the greats.

Ma still performs these pieces regularly. He has presented the complete suites to crowds numbering in the tens of thousands at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles and the Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Chicago, but he also played movements from the suites at the one-year national September 11 memorial service, the funeral for Senator Edward M. Kennedy, and the service held to honor victims of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. In 2019, he featured the Prelude to Suite No. 1 in G major—certainly the best-known movement from the suites—in a video meant to express the many ways in which the arts bring communities together. He issued an invitation for people around the world to submit videos on the theme of self-expression and community building. Many of these were then integrated in the final video.

Yo-Yo Ma has proven his mastery of the classical cello literature. Here he plays the Prelude to Bach’s Suite No. 1.

Despite his success on the concert stage, however, Ma soon embarked on a series of collaborations that brought him into contact with non-classical performers and genres. By doing so, he clearly indicated his belief that examples of “good music” can be found in all traditions, and that quality is determined by the level of execution and creativity that characterize a performance. Early in his journey, Ma collaborated with a team of world-class tango musicians to record The Soul of the Tango (1997). This Grammy-winning album contributed to the elevation of tango from its undeniably humble roots.

Tango

Tango originated in the slums of Buenos Aires, Argentina, in the late 19th century. A popular dance style, the tango was inherently international: It was driven by an instrument brought to South America by German immigrants, the bandoneon (a type of push-button accordion) and capitalized on the syncopated rhythms of rural gauchos (cowboys) and African slaves. The lyrics to early tango songs described the hardships of life in the slums, while the accompanying dance reflected the violence of knife duels, the characteristic posture of the good-fornothing young man, and the ritualistic domination of the female dancer by her male partner. The tango rhythm is built on a quadruple-meter framework with an emphasis on the second half of the second beat.

The tango was at first treated with contempt in its native Argentina. The dance and its accompanying music, after all, were associated with poverty, seedy establishments, and questionable morals. In 1907, however, the tango made a hit in Paris, where it acquired cultural cachet. By the 1920s, it had been embraced around the world, but in the 1930s its popularity began to fade (in part because the Great Depression excited an appetite for more cheerful music). Later in the century, however, Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) would reinvent the tango for the concert hall, composing nuanced and dramatic pieces that were intended for listening, not dancing.

We will consider Yo-Yo Ma’s recording of Piazzolla’s famous “Libertango,” which he recorded with Leonardo Marconi on piano, Antonio Agri on violin, Hector Console on bass, Horacio Malvicino on guitar, and Néstor Marconi on bandoneon. The title incorporates the Spanish word for “liberty”—a reference to Piazolla’s new style, which he launched with the 1974 publication and recording of this composition. Any performance of “Libertango” is immediately recognizable, due to the catchy ostinato played by the bandoneon. The compositions itself is fairly simple: After an introduction, which establishes the ostinato and harmonic progression, we hear the A section twice. This is followed by the B section, which begins with contrasting material but concludes with a variation on the first half of the A melody. Then the ostinato returns, serving as a basis for improvisation.

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | Ostinato | The bandoneon establishes the ostinato while the piano plays a syncopated rhythm known as the tresillo. |

| 0’26” | A | The A melody is played in the cello. |

| 0’54” | A | The A melody is played by the cello and violin in octaves. |

| 1’22” | B | The B melody is played by the bandoneon. |

| 1’37” | A’ | The bandoneon plays a variation on the first half of the A melody, which is now combined with the ostinato; the cello and violin play a countermelody. |

| 1’50” | Ostinato | This time, the cello and violin double the bandoneon on the ostinato. |

| 2’18” | Ostinato with improvisation | The guitar player improvises a solo over the ostinato. |

Throughout the recording, we can clearly hear the tresillo rhythm that is characteristic of much Latin American music. This rhythm has its roots in West African music, and it entered the Latin American mainstream when the traditions of enslaved Africans combined with the folk and popular practices of both indegenous peoples and colonial powers. The same rhythm can also be heard in African-derived musics of the United States, such as ragtime. The tresillo rhythm can be counted as 3+3+2. Each count is a half-beat, such that one measure in quadruple meter contains eight counts. In our recording of “Libertango,” the tresillo rhythm is heard primarily in the piano.

Appalachian Music

At about the same time, Ma also turned his attention to the folk music of the United States. He teamed up with celebrity fiddler Mark O’Connor and renowned bass player Edgar Meyer to record two albums, Appalachia Waltz (1996) and Appalachian Journey (2000), each of which contains fiddle tunes, songs, and new compositions inspired by the American folk sound. The trio did not attempt to reproduce authentic performing styles. Instead, they brought their own skills and backgrounds to the creation of unusual arrangements that balanced traditional material with novel interpretation.

We will consider their rendition of “Fisher’s Hornpipe” from Appalachian Journey. This tune has been convincingly attributed to James A. Fishar, who served as music director at Covent Garden opera house in London in the 1770s. It appeared as “Hornpipe #1” in his 1778 collection of dance tunes. Whether or not Fishar composed the tune, it quickly gained popularity. Today it can be heard all over the British isles, in Canada, and in the United States, where it first appeared in print in 1796. There are countless versions—a symptom of the oral tradition, in which tunes are learned not from notation but by ear. Appalachian fiddlers would most likely have learned “Fisher’s Hornpipe” from travelling dance musicians and adapted it to their own tastes.

For comparison, we might consider Tommy Jarrell’s version of “Fisher’s Hornpipe,” which he learned from his father. This is an example of the traditional fiddling style known today as Round Peak, named after a prominent geological feature near Mt. Airy, NC. Jarrell provides harmony by playing multiple strings at the same time and rhythm by employing syncopated bowing patterns. As such, he doesn’t particularly require accompaniment.

This recording of “Fisher’s Hornpipe” by Tommy Jarrell provides a good example of a traditional Appalachian rendition.

Ma and company’s rendition is quite different. O’Connor is joined on the fiddle by bluegrass legend Allison Kraus. Although they play the same instrument as Jarrell, their technique could not contrast with his more greatly than it does. Each plays only a single melodic line, and does so with great precision and clarity. The slower tempo allows each note to sparkle. Occasionally we can hear vibrato—a technique that Jarrell would never employ. When accompanying other instruments, O’Connor and Kraus evoke some of the same rhythms as Jarrell, but their rendition of the melody is less syncopated.

Perhaps most importantly, the version of “Fisher’s Hornpipe” on Appalachian Journey takes the original tune far outside of its folk framework. When Jarrell plays “Fisher’s Hornpipe,” he simply repeats the A and B strains until he decides that it is time to stop. His version is in the key of D, and it most certainly stays there. O’Connor and Kraus (soon joined by Meyer and Ma) begin with a fairly straightforward rendition of the tune, but after a few times through they switch to a groovy rhythmic pattern. Then, as Ma takes the melody, they modulate (change keys)—twice. Next, each player takes a turn with the A or B section, adding ornaments as if trying to outdo the person who played before. After this, they break into a polyphonic, four-part version of the tune that includes several countermelodies. The recording ends with even more key changes and virtuosic, high-range playing from Ma.

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | A | The two violins play the A strain in harmony (note: Jarrell begins with the other strain, making this his B strain). |

| 0’26” | A | Addition of bass pizzicato. |

| 0’54” | B B | Addition of cello harmony. |

| 1’22” | B’ B’ | The two violinists play a variation on the B strain. |

| 1’37” | A’ A’ | The two violinists play a variation on the A strain. |

| 1’50” | A | The key modulates up one step and the cello plays the A strain, which is extended by a brief concluding passage. |

| 2’18” | A | The key changes again as a solo violin plays the A strain. |

| A | The other violin plays the A strain with additional ornamentation. | |

| B | The cello plays the B strain. | |

| B | The bass plays the B strain. | |

| B B | One violin plays the B strain while the other instruments provide new countermelodies in a polyphonic texture; the key changes for the second statement of the B strain, the last phrase of which is repeated. | |

| A’ A | The A’ variation returns for one statement before the cello plays the A strain. | |

| A’ A | The key modulates up by one step for another A’ statement; it modulates up by yet another step for a cello statement of the A strain. | |

| Coda | A concluding passage echoes the opening motif of the A strain. |

Silk Road Project

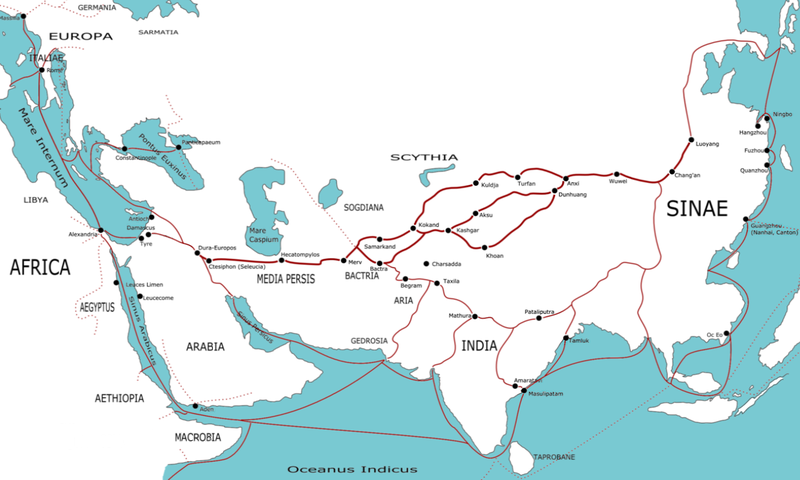

Ma’s most significant and lasting foray outside of the European concert tradition, however, began in 1998 and has carried into the present day. He founded the Silk Road Project with the aim of bringing together musicians and cultures from across the regions formerly traversed by the Silk Road—the trade route, spanning from Italy to Japan, that shaped Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia beginning in the second century BCE. For Ma, the Silk Road was a symbol of intercultural exchange. For two millennia, the Silk Road moved clothing, artifacts, musical instruments, songs, stories, and religious beliefs from one end of the known world to the other. Ma has described the historical Silk Road as “a model for productive cultural collaboration, for the exchange of ideas and traditions alongside commerce and innovation”—values that he wants to promote in the modern world.

Although the Silk Road Project has grown into a multifaceted arts organization—Silkroad—that pursues a variety of initiatives, we will consider only the activities of the Silkroad Ensemble, a collective of international virtuosi who blend the instruments, styles, and techniques of various musical traditions. The ensemble contains nearly sixty members (although only a dozen or so perform together on any given occasion) and has been active across the globe. Its members record albums (seven in the first two decades), give concerts, host festivals, and conduct clinics for students of all ages.

The music played by the Silkroad Ensemble comes from a variety of sources. Sometimes, individual members share traditional pieces from their own cultural backgrounds. The various performers then find a way to interpret that music in a way that makes sense to each of them, and the ensemble works together to develop creative arrangements. Sometimes, the Silkroad Ensemble—like Roomful of Teeth, discussed above—commissions composers to write works for their unique performing forces and abilities. And sometimes, the ensemble adapts pieces of music that have been written for other performers. In all cases, their repertoire blends cultural influences. However, it is very important to Yo-Yo Ma that the Silkroad Ensemble treat its sources with respect and avoid exoticizing non-Western musical traditions—like we saw happen in Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker (Chapter 4).

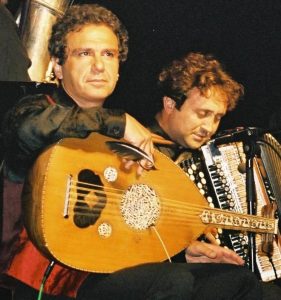

We will consider one of the Silk Road Ensemble’s most popular numbers, “Arabian Waltz.” This piece was written and recorded by the Lebanese composer and oud player Rabih Abou-Khalil in 1996. Although well-versed in traditional Arab music, Abou-Khalil is equally knowledgeable of Western traditions, having studied flute at the Academy of Music in Munich, Germany. His compositions blend Arab scales, textures, and rhythms with influences from jazz, rock, and European concert music. “Arabian Waltz” was written for oud, string quartet (a European ensemble), and traditional Arab frame drums. The original recording featured Abou-Khalil in collaboration with the Balanescu Quartet—an ensemble led by Romanian violinist Alexander Bălănescu that specializes in experimental music.

“Arabian Waltz”

Composer: Rabih Abou-Khalil

Performance: Rabih Abou-Khalil, The Balanescu Quartet (1996)

Clearly, “Arabian Waltz” was a crosscultural work from its inception. In the hands of the Silkroad Ensemble, however, it has absorbed an even greater depth of international influence. We will consider a live performance that the ensemble gave in 2009 at the Park Avenue Armory in New York City. The ensemble, on this occasion, consisted of two violins, viola, cello, string bass, pipa (a Chinese lute—see Chapter 6), sheng (the Chinese mouth organ—see Chapter 4), shakuhachi (a Japanese flute), tabla (North Indian drums—see Chapter 6), various Middle Eastern frame drums (see Chapter 8), and janggu (a Korean drum). This is unquestionably an extraordinary assortment of instruments, each played by a master of the respective tradition.

The Silkroad Ensemble’s performance of “Arabian Waltz” begins just as Abou-Khalil’s had, with the sound of Arab frame drums. From the start, however, the ensemble members leave their unique stylistic fingerprints on this rendition. The principal melody is first heard in the shakuhachi, played by Kojiro Umezaki. Umezaki plays the melody—itself unmistakably Middle Eastern—in a Japanese style, introducing the typical embellishments that are idiomatic to the shakuhachi. Another remarkable contribution comes from the tabla player, Sandeep Das, who likewise plays his instrument just as he would in a North Indian context. In the second half of the performance, Das is featured in a solo that combines the sound of the tabla with the other drums, producing an unprecedented aggregation of percussive timbres.

“Arabian Waltz”

Composer: Rabih Abou-Khalil

Performance: Yo-Yo Ma, The Silkroad Ensemble (2009)

Conclusion

These case studies have explored the expansive definitions of “good music” offered by recent Pulitzer committees, a leading art music ensemble, and one of the most famous living classical musicians. All have agreed that quality can be found in many genres and traditions. We might sum up their values according to the five criteria presented in the introduction.

Was every example in this chapter successful at fulfilling its stated purpose? We’ve looked at a lot of dance music—did it inspire you to dance? Did Shaw’s Partita change the way you think about the possible uses for the human voice? Did Marsalis’s “Work Song” cause you to feel the suffering of his oratorio’s protagonists? Was each of these examples exceptional when compared to others of its type? Is Lamar the best hip-hop artist, and was DAMN. the best hip-hop album of 2017? Is Tehillim a particularly compelling example of minimalist composition? Are the works of Aphex Twin superior to those of other electronic music artists?

Were this examples particularly original? Do they stand out from the field? Is there something about the musical details of Libertango that make it stick in your head? Does the originality of the vision behind Ellington’s Far East Suite qualify it as “better” than other jazz compositions of the era?

The skill of the performer—whether we are talking about Lamar’s accomplished rapping, Roomful of Teeth’s polished singing, Alarm Will Sound’s clever orchestrating, or Ma’s exquisite cello playing—certainly contributes to the quality of each of these examples. Ma in particular has exhibited singular dedication to identify and collaborating with the most accomplished performers from each global tradition. Flawless execution is central to his cross-cultural vision. But what about the skill of the composers? How can we judge that?

Finally, what impact has this music had on society? As an enormously popular performer, Lamar has certainly had an impact—will his legacy shape the future of hip-hop? Copland certainly defined the sound of “Americanness” for generations of composers. That makes him important, but does it make him good? Shaw is still at the beginning of her career—will her future influence determine the quality of Partita in some way?

This book ends as it began: with a long list of questions. None of these questions can be definitively answered, but they are all worth asking. They are worth asking because we listen to music every day, meaning that every day we have the opportunity to engage with an art form that human beings have used to communicate, entertain, and even shape the course of history for tens of thousands of years. We can either listen passively or we can ask questions of what we hear. These questions lead us to listen with greater care, extract more from the music in our lives, and discover new things about the world around us.

Resources for Further Learning

Hasse, John Edward. Beyond Category: The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington. Da Capo Press, 1995.

Online

Andrew Granade and David Thurmaier, Hearing the Pulitzers podcast: http://hearingthepulitzers.podbean.com/

Caroline Shaw: https://carolineshaw.com/

Jazz at Lincoln Center: https://www.jazz.org/

Pulitzer Prizes for Music: https://www.pulitzer.org/prize-winners-by-category/225

Roomful of Teeth: https://www.roomfulofteeth.org/

Silkroad Ensemble: https://www.silkroad.org/

Wynton Marsalis: https://wyntonmarsalis.org/