Unit 4: Music for Political Expression

10 Support and Protest

Esther M. Morgan-Ellis

In the previous chapter, we examined various ways in which nations can be represented by musical means. Our examples included national anthems, pieces of art music that draw from folk sources, and a complete musical tradition with national significance. In this chapter, we will turn our attention to the role of music in political action, and we will see how music can not only represent a nation but also directly influence its character and future.

As we already discussed in the context of national anthems, music can bring people together and inspire them to feel sympathetic toward one another. Music—especially participatory music—can create community. Music can also inspire an emotional response in the listener. These capacities are combined to great effect when music is used to urge a group of people to think or act along specific political lines.

Sometimes, music is employed in support of a political candidate or ideology. The most prominent examples of this include campaign songs, music played at political rallies, and the soundtracks to political advertisements. In all of these cases, music is used to inspire sympathy with a cause or candidate and win the support of the listener. However, the creators of the music in question do not always have a say in its political use. More often than not, music is coopted for political purposes and used in ways that the original artist had never imagined (and may not approve of). In such cases, we see the capacity of music to express meaning beyond its creator’s intent.

Other times, music is used to combat a dominant political force. The most prominent example of this is the protest song, which is used to inspire resistance to an ongoing political action. When music is used to protest ruling powers, however, there is always an element of danger. Those who position themselves in opposition to governments or bosses risk serious reprisal. For this reason, protest music is not always easy to decipher. Sometimes it is overt in its meaning, clearly indicating the objectionable situation and the desired action. Sometimes, however, it is covert, instead disguising its meaning so that only certain listeners will receive the message. In such cases, it can be difficult to determine exactly what a piece of music “means” or even to prove that it is subversive at all. We will examine both overt and covert examples in this chapter.

Musical as Political Advocacy

Campaign Songs

The use of music to rally support for a political cause has a long history. Music has been used around the world to display the power of monarchies, to urge soldiers into battle, and to inspire patriotic support for all manner of governments. Here, we will focus on the role of music in American politics, with special attention given to specific songs that have been used by candidates seeking election to the presidency.

Although we are focusing on campaign songs, those are not the only musical tools that have been employed by American political candidates. Before the rise of mass media, campaigning was conducted in person at events such as rallies, parades, and whistle stops, often to the accompaniment of a local brass band playing popular and patriotic tunes. Today, we are more likely to hear campaign music via television, whether we are watching a televised campaign event or a paid political advertisement. At events, candidates are likely to use popular songs that convey a relevant message, set the right mood, or speak to a desired voting base. In advertisements, we are more likely to hear underscoring similar to that used in television shows and movies. Such music attracts less attention than a popular song, but it plays an equally important role in communicating the candidate’s message.

To see underscoring at work, we might examine two recent television advertisements from a 2016 Republican candidate for governor of Georgia, Casey Cagle. In a spot from early in the campaign, titled “Difference,” Casey touts his humble beginnings, strong personal ethic, and political accomplishments. The music behind his voiceover is bouncy and cheerful. The major mode tells us that this is a message of optimism, while the mid-tempo drumbeat and repetitive, staccato melody notes are reassuring and uplifting. Later in the campaign, however, Cagle—in response to a strong showing by his rival—attempted to construct a new public persona for himself, one that emphasized strength and determination. These qualities are reflected in the television advertisement “About,” which features music that would be equally at home in an action film. The minor mode and suspenseful harmonies keep the listener on edge, while periodic percussive strikes suggest danger and unrest. As musicologist Naomi Graber has observed, the music builds to a climax in parallel with Cagle’s rousing speech, suggesting that Cagle himself is the superhero in this narrative.

In this 2016 campaign ad for Georgia gubernatorial candidate Casey Cagle, the music is bouncy and cheerful.

In this ad from later in Cagle’s campaign, the music is suspenseful.

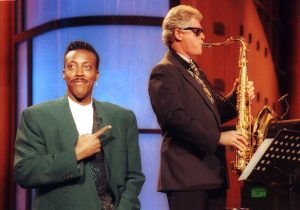

Candidates are sometimes musicians themselves and are therefore able to exploit their own musical skills to win the sympathy and support of the public. In 1886, for example, two brothers—Alf and Bob Taylor—ran against one another in a bid to become governor of Tennessee. Both men were excellent fiddlers, and they not only performed frequently throughout the campaign but also used their love of folk music to establish a down-home identity and connect with rural voters. More than a century later, President Bill Clinton advertised himself as fun-loving and cool by playing saxophone on The Arsenio Hall Show, while Democratic presidential candidate Martin O’Malley garnered attention by playing guitar and singing Taylor Swift’s “Bad Blood” on The View. Although the genres (and skill levels) of these candidate-performers varied widely, all used music to paint themselves as good-humored and relatable.

When it comes to conveying a specific political message through music, song is clearly the best choice, and it has been in use since the beginning of American electoral politics. In the earliest years, election songs were usually parodies. As early as George Washington’s reelection campaign in 1792, supporters advocated their candidates’ causes by writing new words to recent popular songs. This technique could be very effective. Because the melody was already familiar, parody lyrics were quickly learned, sung, and spread. The success of a popular song could even contribute to the success of the campaign that chose to parody that song. In 1840, William Harrison’s campaign song “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” which parodied the familiar “Three Little Pigs,” became so popular that it was widely credited with winning him the presidency.

There is also a long history of presidential candidates relying on endorsements by celebrity musicians to boost their popularity. The earliest example of this came in 1860, when the famous abolitionist singer Jesse Hutchinson wrote a parody song in support of Abraham Lincoln. The song—”Lincoln and Liberty, Too,” set to the tune of “Rosin the Beau”—was a hit, but Hutchinson’s popularity probably contributed just as much to Lincoln’s victory.

New songs have also been written in support of presidential candidates. While this practice dates to the early 20th century, it is particularly widespread today, when anyone can write a song, record a performance, and upload their contribution to social media. Technology has always influenced the role of music in presidential elections. Beginning in the 1930s, the prevalence of radio (and later television) led campaigns to employ songs that were already popular—an approach that proved more effective than the creation of a new song that might or might not prove a hit.

In this chapter, we will consider three such songs. These songs are all quite different in style and message, but they share one important thing in common: None of them were written with any political end in mind. In each case, the presidential campaign coopted the song because it supported the campaign’s political message.

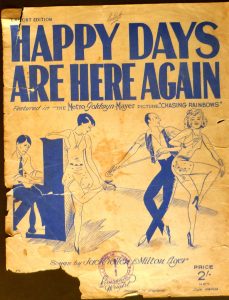

Milton Ager and Jack Yellen, “Happy Days Are Here Again”

The first presidential candidate to coopt a popular song for his campaign was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who in 1932 adopted the recent hit song “Happy Days Are Here Again” to represent his political agenda. Although the song was not created for his campaign and did not communicate an explicitly political message, Roosevelt found that it perfectly captured the spirit of his presidential bid.

“Happy Days Are Here Again”

Composers: Milton Ager and Jack Yellen

Performance: Annette Hanshaw (1930)

It is no surprise that Roosevelt should have been the first presidential candidate to use a popular song in his campaign. The 1920s and 1930s were a time of extraordinary growth in the music recording and broadcast industries, with the result that popular songs were more influential than ever before. The first commercial license was issued to a radio station in 1921, while 1925 saw the invention of the electrical microphone and an accompanying improvement in the quality of recorded and broadcast sound. Due in part to the economic downturn of 1929, radio soon eclipsed the phonograph in popularity. The most successful programming in that era consisted of live musical performances. Roosevelt was the first presidential candidate (and later president) to take full advantage of the radio as a platform for connecting with Americans and spreading his message.

The decision to play “Happy Days Are Here Again” at the 1932 Democratic National Convention was made spontaneously after the man who introduced Roosevelt gave a lifeless and dour speech. Roosevelt’s campaign managers had originally intended to brand him with “Anchors Aweigh” (a nod to his Navy service), but they felt that the occasion called for something more lively and selected “Happy Days Are Here Again” at the last moment. The song proved effective and was used for the remainder of the campaign. In fact, it was such a success that “Happy Days Are Here Again” was associated with the Democratic Party for many years to come.

In 1932, a song like “Happy Days Are Here Again” would have had particular resonance with Americans, who were experiencing the worst effects of the Great Depression. The 1930s saw a public clamor for escapist films, theater, and songs. Almost no popular songs from this era reference the difficulties that plagued Americans following the stock market crash of October 1929. Instead, they celebrate good times, affluence, and carefree living.

The authors of “Happy Days Are Here Again”—composer Milton Ager and lyricist Jack Yellen—were themselves the beneficiaries of fortunate timing, for they wrote their song just before the onset of the Great Depression. “Happy Days” was commissioned by MGM for inclusion in an early sound film, Chasing Rainbows (1930). While waiting for the film to be released, however, Ager and Yellen provided their new song to bandleader George Olsen, who performed regularly at Hotel Pennsylvania in New York City. Olsen’s band premiered “Happy Days” on October 24, 1929—the day of the crash. Olsen supposedly called on his soloists to “sing it for the corpses,” a reference to the morose diners who had just lost their life savings. As Yellen recalled, “After a couple of choruses, the corpses joined in, sardonically, hysterically. Before the night was over, the hotel lobby resounded with what had become the theme song of ruined stock speculators as they leaped from hotel windows.”

“Happy Days Are Here Again” went on to become a major hit. It appealed to listeners who reveled in the irony of the lyrics (“happy days” were certainly not anywhere to be seen), but it also embodied the American spirit of optimism and perseverance in the face of extreme difficulty. The lyrics—like those of most successful songs—are not about any particular event or situation. Instead, they speak in broad terms, bidding farewell to “sad times” and “bad times” before celebrating the fact that “the skies above are clear again” and calling on all to “tell the world” that “happy days are here again.”

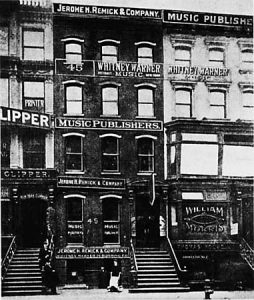

“Happy Days Are Here Again” was a project of a songwriting industry known as Tin Pan Alley. The main product of Tin Pan Alley song publishers was sheet music, which consumers would purchase so as to be able to perform hit songs in their own homes. By 1929, sheet music sales had already been eclipsed by phonograph sales, and radio was further eating into the popular music market share. Still, songwriting teams, usually in the employment of Tin Pan Alley publishers, continued to crank out potential hits into the 1940s. (The name “Tin Pan Alley” refers to the discordant sounds of cheap pianos being played in the many publishing houses located on a single block in Manhattan.)

During the Tin Pan Alley era, songs were not often associated with individual performers. Instead, hit songs were recorded by all of the prominent singers, each of whom was expected to perform a common repertoire. “Happy Days Are Here Again” was first recorded in November 1929 by Leo Reisman and His Orchestra, but this was only the first in a parade of renditions by a variety of popular singers. We will consider the 1930 recording by Ben Selvin and His Orchestra, with Annette Hanshaw on vocals.

Ben Selvin (1898-1980) holds the honor as the most productive recording artist in American history, having recorded as many as 20,000 individual tunes. It is difficult to make an exact count because Selvin recorded under dozens of different names for all of the major record labels of his era. This was a typical practice, since performing artists were required to sign exclusive contracts with recording companies. The use of pseudonyms allowed an artist to triple or quadruple their income by recording with a variety of labels. As a producer at Columbia Records, Selvin also oversaw the creation of recordings by other artists. His catalog includes some of the finest records made in the early 1930s.

Annette Hanshaw (1901-1985) was among the countless singers who performed and recorded with Selvin’s band. She was also very famous in her own right, being voted the best female popular singer in a 1934 Radio Stars magazine poll. Hanshaw, however, later confessed that she detested performing and could not stand her own records. She loved music but became very nervous in front of a microphone and was dissatisfied with her abilities as a singer.

Selvin and Hanshaw’s recording of “Happy Days Are Here Again” is typical of 1920s-era sweet jazz. This type of music was intended primarily for dancing, and it could be heard in upscale urban hotels, ballrooms, and on the radio. Selvin’s band contains instruments that we associate with jazz today, such as saxophones, trumpets, trombones, and piano, but—in keeping with the standard of the era—it also contains a violin section, and the bass line is played on the tuba instead of the string bass. The tempo is lively and the beat is clearly articulated by the rhythm section (piano and tuba).

Ager and Yellen’s jazz-influenced tune is highly syncopated, meaning that melody notes often fall between beats. We can hear this in the chorus: The word “happy” falls on the beat, but the words “days” and “are” come after the beat. (Try clapping the pulse while reciting the lyrics in rhythm to see how this works.) This pattern is repeated with the next phrase, in which “here” falls on the beat but the second syllable of “again” come off the beat. Selvin’s band makes this pattern sound even more exciting by shortening the melody notes that fall on the beat.

The form of this recording is also typical of the era. Although the song “Happy Days Are Here Again” technically begins with a verse, Selvin chooses to open his rendition with the much catchier chorus. After singing through the chorus once, Hanshaw sings the verse, which is much shorter than the chorus and also in the minor mode. This provides welcome contrast, but the change in mood doesn’t last long. Next, we hear a rendition of the chorus by an anonymous trio of male singers. Finally, we get an instrumental version, with the male singers joining in for the closing phrase. In short, most of the recording is taken up by three complete turns through the chorus—which, by the end of the three minutes, is firmly lodged in the listener’s head.

This approach to the production of popular music—extreme repetition, softened by a brief excursion into contrasting material—is still with us today. Although the forms, sounds, and lyrics have all changed, record producers continue to foreground the most memorable musical material while finding opportunities to introduce contrast. This delicate balance between too much repetition (which would make a song annoying) and too little (which would prevent it from being memorable) characterizes the eternal formula for successful popular music.

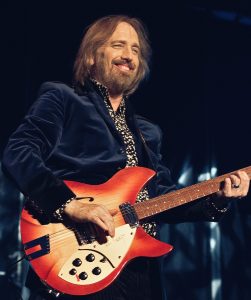

Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne, “I Won’t Back Down”

Tom Petty’s 1989 hit “I Won’t Back Down” is an obvious choice for a political candidate. In fact, it is so well-suited to the campaign trail that half a dozen candidates have employed it in just the first two decades of the 21st century. It was also used to voice a non-partisan political message following the September 11 terrorist attacks. At the same time, at least one candidate’s attempt to coopt the message and popularity of “I Won’t Back Down” backfired. We will try to understand why this song has been so useful in the context of political discourse and consider the risks of coopting the creative work of a celebrity for partisan purposes—especially when that celebrity is politically active.

“I Won’t Back Down”

Composer: Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne

Performance: Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers (1989)

By the time he released “I Won’t Back Down,” Tom Petty (1950-2017) was already a rock music superstar. Petty was born and raised in Gainesville, FL, where he dropped out of high school to join a band. He was inspired by Elvis Presley and The Beatles, whose success proved to him that it was possible for a regular, working-class kid to make it in music. Although Petty only achieved local celebrity in his first decade as a rock musician, the late 1970s saw the meteoric rise of his band Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, which recorded a string of successful albums between 1976 and 1987. Although the Heartbreakers would reconvene in the early 1990s and continue to release albums until just a few years before Petty’s 2017 death, Petty took a hiatus in 1988 to join George Harrison’s group the Traveling Wilburys. During this same period, Petty also released his first solo album, Full Moon Fever. The lead single from this album was “I Won’t Back Down.”

Half of the songs on Full Moon Fever were cowritten by Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne, an English musician and founding member of the Traveling Wilburys. It is common for popular songwriters to work in pairs. This strategy has proved successful since the early 20th century, when Tin Pan Alley songwriters teamed up to produce hits. Many songwriters find that this approach aids productivity, since the contributors can help one another out of creative difficulties and suggest improvements to the music or lyrics. Lynne also produced the album and is, therefore, in part responsible for the sound of “I Won’t Back Down.”

The success of “I Won’t Back Down”—both as a popular song and as a political soundtrack—can be traced to its straightforward message. Like “Happy Days Are Here Again,” “I Won’t Back Down” does not refer to any particular event or circumstances. We don’t know what the singer is standing up for, or against whom he is resisting, or why he is in a position that requires he stand his ground. All we know is that, despite “a world that keeps on pushin’ me around” and “draggin’ me down,” the singer “won’t back down.”

The music admirably communicates this message of steadfast endurance. “I Won’t Back Down” is set to a medium rock tempo—not so fast as to feel frantic but not so slow as to feel lethargic. The music sounds as if it—like the singer—could carry on this way forever. The sung melody has a protracted melodic rhythm, meaning that the individual note values are long and unhurried. Petty’s unaffected drawl further convinces us that he is not to be moved, while the relaxed guitar solo underscores the point. “I Won’t Back Down” is, naturally enough, in the major mode, but the accompaniment prominently features a minor chord, heard under the word “won’t” in the title line. This tinges the lyric with seriousness of purpose. Although the singer is not overly concerned, he is not taking the threat lightly.

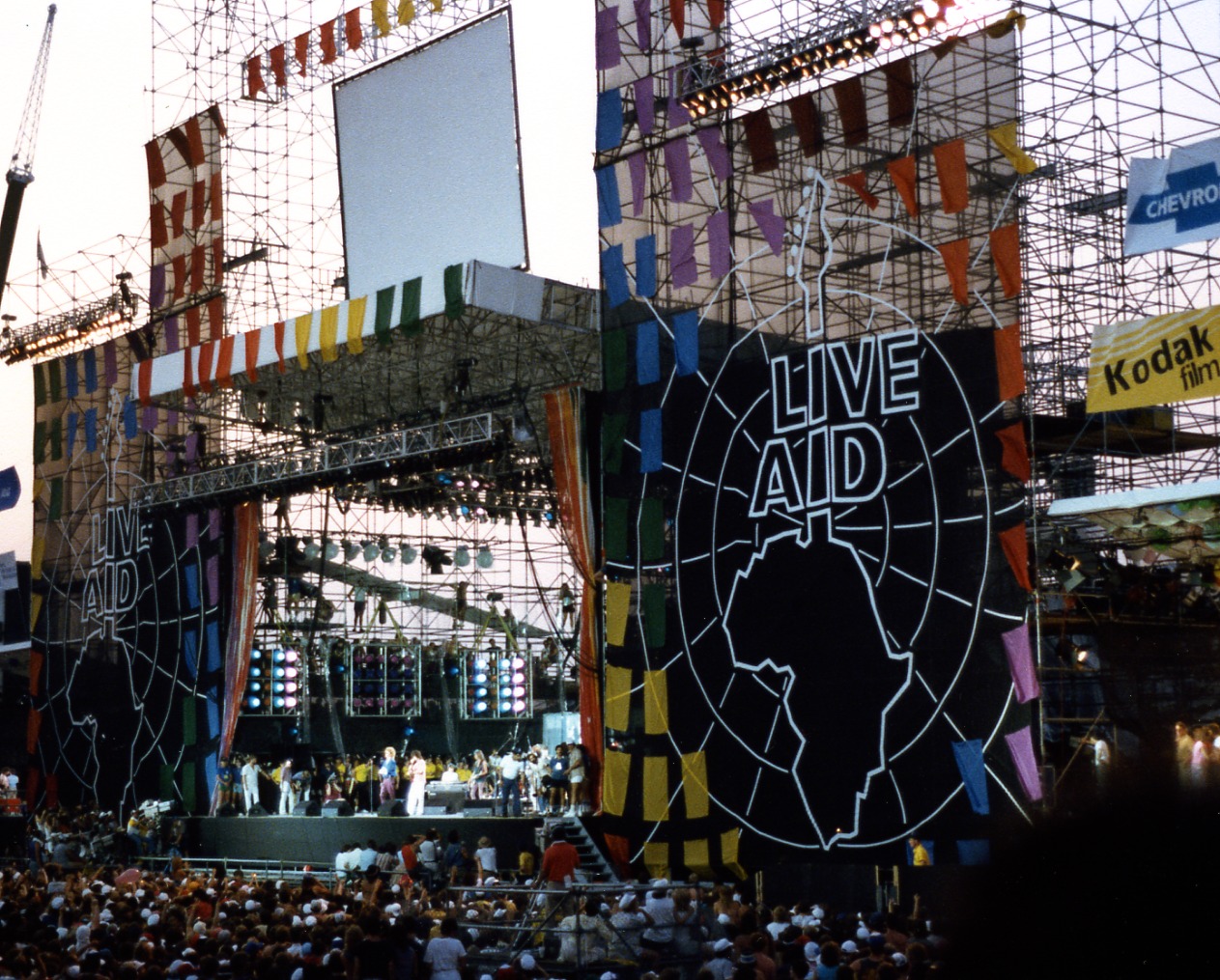

“I Won’t Back Down” first made political headlines in 2000, when George W. Bush used it at events during his presidential campaign. The song seemed an excellent choice, but it became a liability when Petty protested, sending the campaign a cease-and-desist letter and demanding that they quit using his music. Bush’s campaign staff might have known better: Petty had already indicated a penchant for political speech as a musician and had aligned himself with various activist causes. In 1979, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers performed in a Madison Square Garden concert intended to raise support for the dismantling of nuclear power plants, while in 1985 they took to the stage for the famous Live Aid concert in Philadelphia, which raised funds to combat famine in Ethiopia. And in 1992, Petty had written the song “Peace in L.A.” in response to the Rodney King riots, donating all proceeds to charity. Although none of these were explicitly left-wing causes, Petty was certainly aware of his power as a political agent, and he knew that music could make a difference in a political struggle. After the 2000 election, Petty performed “I Won’t Back Down” at Al Gore’s concession speech, thereby clearly sending the message that he intended to retain control over how his music was used.

Petty, however, did not always interfere when politicians coopted his music. During the 2008 presidential campaign, for example, “I Won’t Back Down” was used by Democratic candidates Hillary Clinton and John Edwards, but also by Republican candidate Ron Paul. In 2012, he again made no comment when “I Won’t Back Down” was played at the Democratic National Convention. That same year, however, he issued another cease-and-desist letter to Representative Michele Bachmann, who used his song “American Girl” to launch her presidential campaign. Petty, of course, was not the first rock star to object to the coopting of his hits—and also not the last. All modern presidential campaigns are accompanied by a chorus of popular recording artists asking that candidates stop using their music. It’s not clear why Petty accepted some uses of his songs and rejected others, but it is entirely clear that he understood the power of his music and celebrity.

Carl Orff, Carmina Burana

Although popular song has been the preferred political vehicle of the past century, art music is also ripe for exploitation. Indeed, much of the music that we enjoy in concert halls and opera houses today was created on behalf of political regimes for the purpose of cementing their power. Monteverdi’s opera Orpheus, for example, was intended to display the wealth of the Gonzaga court and solidify its position in the eyes of visitors. Although the plot of Orpheus is not explicitly political, many of the Italian operas of the following two centuries portrayed monarchs as benevolent and wise father figures ordained by God for the safekeeping of their people—an image that did much to mediate potential unrest. The modern symphony orchestra, in its own turn, might be traced to a court in Mannheim, where an orchestra was used to advertise the splendor of Charles III Philip, who ruled a large region in what is now Germany.

Orff and the Nazi Party

Here, however, we will examine a 20th century instance of concert music turned to political use. While Carl Orff (1895-1982) did not set out to write a political piece of music, his scenic cantata Carmina Burana was embraced by the Nazi Party, the leaders of which believed that it conveyed many of their values and could be put to use for the purpose of riling up crowds and building communal sentiment. Beginning in 1940, Carmina Burana was frequently performed at Party rallies and government functions, in which context it both exemplified “good” Nazi music and was used to boost enthusiasm for the government and its activities.

Carl Orff was not himself a member of the Nazi Party. After the war, he was investigated by the American denazification authorities, who cleared him of collaboration charges and authorized him to continue his professional work. All the same, Orff thrived under the Nazi regime, and he certainly didn’t use his position of relative influence to resist the regime’s activities. He never denied the Nazis permission to use his work, and on several occasions actually wrote music on their behalf. Any attempt at subversion, of course, would probably have culminated in Orff’s execution. In short, he behaved as many Germans of the era did, neither supporting nor condemning the Nazis.

Orff wrote a large number of theatrical works, many of which expressed his theory of “elemental music.” In attempting to recapture the power of ancient Greek drama, Orff advocated for a unified stage art that combined music, dance, poetry, image, design, and theatrical gesture. If this sounds familiar, we have already seen other creative figures attempt to revive the arts of ancient Greece (the Florentine Camerata, discussed in Chapter 4) and develop an all-encompassing approach to musical theater (Richard Wagner, discussed in Chapter 3). Indeed, Orff himself was responsible for the 1925 revival of the most famous opera produced under the Camerata’s influence, Claudio Monteverdi’s Orpheus. His greatest impact, however, was in the field of music education. He co-founded the Günther School in Munich in 1924 and taught music there until the end of his life. The techniques he developed for working with young children are still in use today.

Carmina Burana

Carmina Burana—certainly Orff’s most successful composition—is what he termed a “scenic cantata.” A cantata is a multi-part work for voice(s) and accompaniment. We examine two cantatas elsewhere in this volume: Barbara Strozzi’s Lagrime mie for solo soprano and basso continuo (Chapter 8) and Johann Sebastian Bach’s Sleepers, Wake for soloists, choir, and orchestra (Chapter 11). Cantata, however, is a flexible designation. Just as Strozzi and Bach’s cantatas have little in common, Orff’s cantata will in turn bear only a limited resemblance to other cantatas you might have encountered. His addition of the term “scenic” indicates that his cantatas are meant to be staged. Orff envisioned dramatic performances complete with sets, costumes, pantomime, and dancing. Carmina Burana was indeed presented as a dramatic spectacle in its early days, although now you are more likely to encounter it as an unstaged concert work.

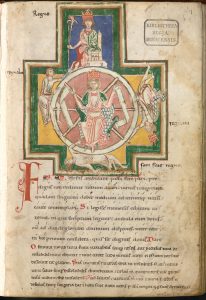

Today, Carmina Burana seems to have completely shed its wartime significance. Few people know that it was ever used as Nazi propaganda, and it is widely enjoyed by audiences and performers. This is in part possible because the text has nothing whatsoever to do with politics, war, or Nazi values. Indeed, the text is nearly a thousand years old: Orff extracted it from a medieval manuscript of the same name. “Carmina Burana” is Latin for “Songs from Benediktbeuern,” and refers to a volume of poems written primarily in the 11th and 12th centuries. The manuscript containing the poems was discovered at a Benedictine monastery in Benediktbeuern (now a municipality in Bavaria) and is prized as one of the most significant collections of what are known as goliard songs.

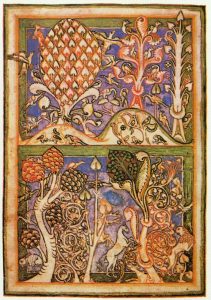

Goliards were, in modern terms, carousing college dropouts. Many were younger sons from wealthy families. Because only the eldest son could inherit, younger sons were sent to monasteries or Catholic universities, where they were educated in theology and prepared to enter the clergy. Many of these young men, however, had no affinity for the religious life and instead preferred to pursue more earthly pleasures. Because they had been well educated, goliards were able to leave a record of their satirical poems and racy songs. Most of these were written in Latin, the language of the Catholic church, although some are in the vernacular languages spoken by the goliards.

The songs in the Carmina Burana manuscript address all of the topics that might be of interest to young men who enjoy having a good time: the fickleness of fortune and wealth, the ephemeral nature of life, the joy of the return of Spring, drinking, gluttony, gambling, and lust. Few of the texts can be associated with specific melodies, meaning that a composer who wanted to borrow them would be obliged to create new musical settings. Orff did so, although he often sought to imitate the melodic shapes and modes of Gregorian chant (see Chapter 11 for an example).

Taken as a whole, however, Orff’s music is far removed from that of the medieval Catholic church. He wrote for an enormous ensemble consisting of three vocal soloists, three choirs (two mixed and one boys’), and a large orchestra complete with an eighteen-piece percussion section and two pianos. His music was inspired by Igor Stravinsky’s primitivist ballets (see Chapter 3), which used repetitive melodic figures (ostinatos) and jarring rhythms to evoke a pre-modern social order.

To create his scenic cantata, Orff first chose twenty-three poems from the manuscript and organized them into scenes, which address the topics of fate, springtime, drinking, and love. The first and last scenes are identical, for they portray “Fortune, Empress of the World.” The vision of fortune as a great wheel that turns incessantly can be found throughout the Carmina Burana manuscript, where it is represented both in verse and image. It therefore seemed natural to Orff that his cantata should end as it had begun, with a mighty chorus announcing the power of fate to shape our lives. We will examine four musical selections, one representing each of the four themes explored in Carmina Burana.

“O Fortune”

The opening chorus, “O Fortune,” is certainly the most famous part of Carmina

Burana. It has featured in dozens of films, television shows, commercials, and

video games, and has even been employed by professional sports teams. Its text

consists of three stanzas:

O Fortune, like the moon of ever changing state, you are always waxing or waning; hateful life now is brutal, now pampers our feelings with its game; poverty, power, it melts them like ice.

Fate, savage and empty, you are a turning wheel, your position is uncertain, your favour is idle and always likely to disappear; covered in shadows and veiled you bear upon me too; now my back is naked through the sport of your wickedness.

The chance of prosperity and of virtue is not now mine; whether willing or not, a man is always liable for Fortune’s service. At this hour without delay touch the strings! Because through luck she lays low the brave, all join with me in lamentation!

Translation by Gavin Betts. Used with permission.

“O Fortune” from Carmina Burana

Composer: Carl Orff

Performance: Orchestra and choir of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, conducted by Eugen Jochum (1968)

The music is simple in the extreme. After a shockingly loud introduction, in which the full chorus and orchestra sound a series of accented chords, the instruments of the orchestra set an ostinato into motion. The ostinato contains only four pitches, each of which is sharply accented. Over the top of this ostinato, the chorus sings a melody constructed out of repeated melodic and rhythmic fragments. Almost all of the melodic motion is conjunct and the entire melody occupies the tiny range of a fifth. Some commentators have compared this melody to Gregorian chant, while others have remarked upon its folk-like qualities.

The first two verses are musically identical, but the third is marked by an explosion in volume. The sopranos repeat their melody, but they do so an octave higher than before. Likewise, high-register instruments join the ostinato. In the final moments of the movement, the pattern finally breaks as a new six-note ostinato takes us to the final thrilling chord. Orff’s music certainly conveys the power and inescapability of fate!

“Dance”

The next selection we will consider has quite a different mood. It is an instrumental movement from the springtime scene entitled simply “Dance.” All the same, “Dance” shares a great deal in common with “O Fortune.” Orff opens the movement with a series of dramatic chords, after which he uses ostinatos to underpin a melody that is itself full of melodic repetition. And once again, that melody moves primarily by step and occupies only a small range. “Dance” feels a bit more rhythmically unpredictable than “O Fortuna.” This is due to the fact that the meter changes frequently, which prevents a steady pulse from being established (try tapping your toe along to the music—it should be very difficult). A further sense of liveliness is produced by metric disagreements between the ostinato and the melody: Often, the strong pulses in each layer do not line up.

“Dance” is in a ternary (A B A) form. The first A section features strings, which composers often employ to bring pastoral scenes to life. The flute, which carries the melody in the B section, is even better suited to shepherd life. This middle passage is unusual, for we hear only the flute and timpani—a rare paring to be sure. Finally, the A melody returns in the horns and trumpets. As in “O Fortune,” the music builds to an exciting and noisy final chord.

“Dance” from Carmina Burana

Composer: Carl Orff

Example: Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Donald Runnicles (2002)

“Once I had Dwelt on Lakes”

Our third example will provide still further contrast, for it features one of the humorous texts that Orff chose to include in his cantata. “Once I had Dwelt on Lakes” is narrated from the perspective of a roast swan as he awaits his fate on a banquet table:

“Once I had Dwelt on Lakes” from Carmina Burana

Composer: Carl Orff

Performance: Gerhard Stolze, Orchestra and choir of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, conducted by Eugen Jochum (1968)

Once I had dwelt on lakes, once I had been beautiful, when I was a swan.

Poor wretch! Now black and well roasted!

The cook turns me back and forth; I am roasted to a turn on my pyre; now

the waiter serves me. Poor wretch! Now black and well roasted!

Now I lie on the dish, and I cannot fly; I see the gnashing teeth. Poor wretch!

Now black and well roasted!

Translation by Gavin Betts. Used with permission.

Each of the three stanzas concludes with a refrain, which is sung by the men of the choir. The part of the swan is played by the tenor soloist, who sings at the top of his range. The resulting sound, which is often tense and pinched, can be heard as an imitation of the swan’s own voice. We also hear the swan in the opening bassoon solo—played at the top of that instrument’s range. Finally, the fluttering sound in the strings and flute might capture the swan’s trepidation as he contemplates his impending fate. Once again, repetitive melodies—melodies that are also, in the case of that sung by the choir, stepwise and limited to a narrow range—are underpinned by ostinatos.

“It is the Time of Joy” & “Sweetest of Men”

Finally, we will examine a selection—or, to be fair, a pair of selections—from the scene dealing with love. We are not talking about romantic love, however, but carnal lust. The texts to “It is the Time of Joy” and the short response number “Sweetest of Men” outline the courtship of a woman by a young man who is consumed with desire. She ultimately accedes:

“It is the Time of Joy” from Carmina Burana

Composer: Carl Orff

Performance: Gundula Janowitz, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Orchestra and choir of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, conducted by Eugen Jochum (1968)

“Sweetest of Men” from Carmina Burana

Composer: Carl Orff

Performance: Gundula Janowitz, Orchestra of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, conducted by Eugen Jochum (1968)

It is the time of joy, O maidens, now enjoy yourselves together, O young men.

Refrain: Oh, oh, I am all aflower, now with my first love I am all afire, a new

love it is of which I am dying.

I am elated when I say yes; I am depressed when I say no. Refrain

In the time of winter a man is sluggish, when spring is in his heart he is

wanton. Refrain

My innocence plays with me, my shyness pushes me back. Refrain

Come, my mistress, with your joy; come, come, fair girl, already I die. Refrain

Sweetest of men,

I give myself to you wholly!

Translation by Gavin Betts. Used with Permission.

This musical example is dominated by percussion and piano, which keep up a lively rhythmic accompaniment. The verses are sung alternately by the women and the men of the choir, while the refrain is sung alternately by the baritone soloist and the boys’ choir. The complete vocal forces come together for the final verse/refrain pair. Every pair is sung to the same melody, but the timbral variations introduced by the changes in singers keeps the music from getting stale.

“Sweetest of Men” could hardly be more different from “It is the Time of Joy.” In place of the percussive ostinatos, the orchestra sustains a single harmony. The solo soprano soars to the top of her range, carrying the fifth vowel of her text through a long passage of notes. This is known as a melismatic passage, and it contrasts sharply with the syllabic character of the previous number, in which every syllable was paired with a single note. The selection can be heard in fairly graphic terms as the satisfying fulfillment of a sexual encounter, which was communicated by all the bumps and bangs of the previous number.

This particular moment almost got Orff into trouble with the authorities, for the Nazi regime did not take kindly to the glamorization of improper social behaviors. (The Soviet regime was equally prudish, as exemplified by its response to Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsenk District, which is detailed in the final section of this chapter.) In fact, Herbert Gerigk, a leading ideological voice in the Nazi Party, registered several objections to Carmina Burana when he reviewed the premiere: He found fault in the language of the text, which was incomprehensible to German listeners; the primitive character of the music, which he considered to reflect the influence of jazz (a musical style that was widely denigrated and strictly forbidden); and the “loose morals” on exhibit in the cantata.

Nonetheless, it was another interpretation of Carmina Burana that won official acceptance. The Nazi official Horst Büttner regarded the work as exemplifying “the radiant, strength-filled life-joy of the folk.” He also pointed out that the poems were artifacts of German folk heritage, and therefore to be treasured as national literature. Finally, Büttner connected the rhythms and melodies with German folk music, thereby identifying Carmina Burana as an authentic expression of German identity.

When used in the context of political gatherings, Carmina Burana had the added value of encouraging powerful and unambiguous collective emotional reactions. It seemed to echo Hitler’s call for Germans to “think with your blood.” This was the kind of music that could inspire support for the regime on a purely physical level.

Music as Political Protest

Just as music can be used to express confidence in a candidate or government or to win support for a political cause, it can also be used to protest the actions of those in power. Because these two objectives are similar, campaign songs and protest songs generally have certain characteristics in common. The elements that usually make for a good campaign song—non-specific lyrical content, catchy melody, energetic rhythms, hopeful mood—also tend to make for an effective protest song. In both cases, after all, the song is supposed to inspire those who hear it to rally in support of a political action.

However, there are some important differences in the ways that campaign songs and protest songs are used. Campaign songs are usually broadcast over loudspeakers at live events or perhaps performed by a band. They might also be included in television advertisements. In all of these contexts, campaign songs are passively consumed by the audience. They play an important role in setting a mood and establishing a campaign’s brand, but their potential effectiveness is limited to their sound and lyrics.

Protest songs, on the other hand, are most often performed by the protesters themselves. They are not passively consumed but collectively voiced in a participatory context. Therefore, the sound of the song as a commercial product is not of paramount importance. What does matter is that the song be fairly simple in terms of text and melody so that participants can quickly learn it, and so that even the least accomplished singer will be able to join in.

Protest songs differ from campaign songs in another important way as well, for they are likely to be expressly written for political use. At the same time, protest songs are often coopted by movements that are far removed from their original context and may or may not have the explicit support of the song’s creator. And, just as a non-political song can be adopted by a campaign, a non-political song can be deployed in support of a protest movement. Once again, therefore, we will see how creative artists cannot be guaranteed to retain control over the meaning or use of their own works.

Protest Songs

Florence Reece, “Which Side Are You On?”

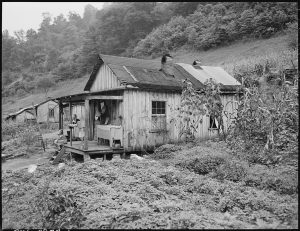

Our first example was certainly intended as a protest—and a pointed, personal protest at that. The creator of this song was not a popular performing artist but an impoverished union organizer in rural Kentucky, unknown outside of her own community until long after the song was written. She did not have commercial success on her mind but, rather, the immediate survival of her family, which had been targeted for destruction by a powerful oppressive force.

Florence Reece (1900-1986) was the daughter and wife of coal miners. Born in Tennessee, she married Sam Reece at the age of sixteen and moved with him to Harlan County, Kentucky. It was here that a bloody conflict between mine workers and owners, now known as the Harlan County War, would play out between 1931 and 1939. In addition to fighting to protect her family, Florence documented the period in poems and songs that both reflected her desperate situation and called on fellow members of the mining community to maintain the struggle.

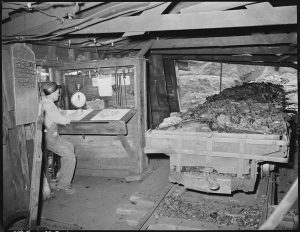

During World War I, the coal mining industry enjoyed a boom in production. Coal, after all, was needed for the production of steel, of which the war effort required an endless supply. Although coal companies saw the greatest profits, individual coal miners also lived comfortably during this period: Because there was enormous demand for their labor, the United Mine Workers (UMW)—the union that represented coal miners—was able to secure high wages on their behalf.

Following Armistice, however, coal companies failed to scale back their production, with the result that the market was overwhelmed and prices dropped precipitously. Many coal miners were fired, while those who remained on the job saw their wages cut again and again. Then, in 1929, the Great Depression hit, and conditions for mine workers became even worse. The UMW found that it had lost its bargaining power and withdrew, leaving workers without advocacy.

Miners who lost their jobs or found the conditions intolerable could not simply leave. To begin with, work was scarce in the early 1930s. It was the structure of the mining industry, however, that posed the greatest challenges. Miners lived in company towns that were owned and operated by the mining conglomerates. They could not buy their own homes and were reliant on the company store for household goods and groceries—stores that often inflated prices and encouraged mine employees to go into debt. Miners who wanted to leave often were not able to do so, since they owed money to their employer, while those who lost their jobs simultaneously became homeless.

Another union stepped in to fight on behalf of the desperate miners, whose labor was still necessary to keep the industry going. That union, the National Miners Union, was backed by the American Communist Party, and it was willing to undertake extreme actions. The mine owners, on the other hand, were able to buy the support of local sheriffs, the state militia, and the court system. They even hired Chicago gangsters to take out union leaders. The ensuing conflict resulted in countless deaths on both sides, including hundreds of children and infants who starved to death or were denied medical services by the company doctors.

One particular skirmish prompted Florence Reese to create “Which Side Are You On?” Sam Reece was a union leader and, therefore, a target for the company-backed law enforcement. One day, Sheriff J.H. Blair arrived at the Reece home with his men. They ransacked the house in front of Florence and her seven terrified children and then settled in to wait for Sam, with the intention of shooting him dead when he arrived. Sam, however, had been warned about the raid and did not return home that day. After the men left at nightfall, Florence tore a calendar off the wall and wrote the text to her song on the back.

“Which Side Are You On?”

Composer: Florence Reece

Performance: Florence Reece

Florence Reece was a lyricist, not a composer, and when she wrote songs, she sang the words to familiar pre-existing melodies. For “Which Side Are You On?” she chose the melody of an old Baptist hymn, which she knew as “Lay the Lily Low.” The same melody is also used for the traditional ballad known variously as “Jack Munro,” “Jack Went A-Sailing,” and “The Maid of Chatham.” The ballad is probably of British origin and, therefore, can be considered a likely source for the hymn melody known to Reece.

This rendition of “Jack Went A-Sailing” was recorded in 1968.

The hymn melody was a natural and effective choice. As a committed Christian, Reece would have been likely to select tunes that she had learned in the context of worship. This particular tune is simple and easy to sing. It is also a bit ominous, given its minor mode and descending melody—the last note of each phrase is the lowest. As a result, the tune cannily captures the spirit of Reece’s message.

Reece’s message is straightforward and unadorned. She does not rely on poetic imagery or metaphor—and she doesn’t need to. In the first stanza, she praises the union. In the second, she announces that victory is assured. In the third, she makes it clear that everyone involved in the conflict must choose a side, calling out the sheriff who threatened her family by name. In the fourth, she brings in her concern about the children of miners. In the fifth, she exhorts miners to be honest and brave. In the sixth, she proclaims her mining heritage—and incorporates her only flight of poetic fancy, referring movingly to her deceased father as “in the air and sun.” And in the seventh (not heard in our recording), she returns to the theme of collective strength through unionization. The chorus—a simple question, repeated four times—drives home the message without any ambiguity.

Reece did not record her song until much later in life. When she did so, she sang in the simple, unadorned style of many Appalachian ballad singers. She sings without accompaniment, just as she would have in 1931. Her words have a force that comes not only from her personal experiences but from her knowledge that they continue to be relevant. Although the Harlan County miners emerged victorious in 1939, another conflict would take place in 1973, when 180 miners employed by the Eastover Coal Company’s Brookside Mine and Prep Plant went on strike for improved working conditions and decent wages. Reece joined the strikers in solidarity, and her rendition of “Which Side Are You On?” before a crowd of miners and their families was recorded in the documentary Harlan County, USA.

Reece’s song first gained mainstream popularity when it was recorded in 1941 by the Almanac Singers, a folk revival group based in New York City and led by a young Pete Seeger. The Almanac Singers were actively engaged with left-wing politics, and they were interested in supporting the labor movement. Their version employs guitar and banjo accompaniment and features a large group of singers on the chorus—a sonic representation of the collective workers represented by the union. The song was later recorded by dozens of other artists, and it has been used in protests around the world.

“Which Side Are You On?”

Composer: Florence Reece

Performance: The Almanac Singers (1955)

Bob Dylan, “Blowin’ in the Wind”

It is not surprising that a folk revival group like the Almanac Singers would record Reece’s protest song. Participants in the folk revival movement were almost universally preoccupied with social justice issues, and its singers would both record and create countless protest anthems. In fact, it is difficult to select a representative example. Bob Dylan’s classic “Blowin’ in the Wind,” however, will serve our purpose well. It will allow us to consider the connection between style and message, to examine the typical characteristics of a successful protest song, and to consider the ways in which a protest song can mean something to listeners and singers) that was never intended by its creator.

“Blowin’ in the Wind”

Composer: Bob Dylan

Performance: Bob Dylan (1963)

The folk revival movement began in the 1930s, when young people in northern cities began to take an interest in the songs and tunes of rural Southern musicians. The movement was largely driven by field collectors, the most prominent of whom were the father-son team of John and Alan Lomax. Collectors would travel through rural communities recording folk artists. In fact, it was Alan Lomax who collected “Which Side Are You On?” from Florence Reece in 1937. Sometimes, collectors would actually bring rural performers up north to perform on college campuses and at folk festivals. For the most part, however, the folk revival was driven by northern musicians performing the songs they learned from field recordings, using the same acoustic instruments—especially guitar—that were common in the south.

Although the folk revival was sparked during the Great Depression, it did not exert mainstream influence until the 1960s, when the counterculture movement adopted folk music as a favored means of expression. The 1960s saw extraordinary social upheaval, as young people rebelled against the conservative social values of the post-WWII era, marginalized groups fought for civil rights, and anti-war activists protested US involvement in Vietnam. Folk music quickly became an important vehicle for political speech.

Most of the central figures in the folk revival did not become famous performing authentic folk music. Instead, they wrote and recorded original songs in a folk style. Perhaps the most influential and respected of these artists was Bob Dylan, who produced an extraordinary catalog of songs featuring his own evocative poetry. Dylan was regarded as a folk singer because he accompanied himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica, but he was more interested in expressing himself creatively than in preserving music of the past.

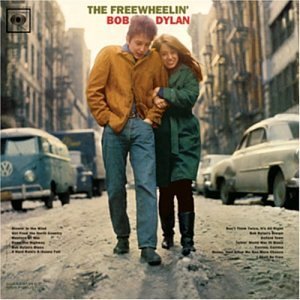

Bob Dylan was born Robert Allen Zimmerman to Midwestern Jewish parents in 1941. He moved to New York City in 1961, where he legally changed his name while still using a variety of pseudonyms to record and publish his creative work. Dylan’s eponymous first album, released in 1962 by Columbia Records, consisted mostly of familiar folk and gospel songs. It was hardly a success, barely breaking even in financial terms, and skeptics within Columbia recommended that his contract be terminated. Dylan’s producer stood by him, however, and his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), was considerably more successful. The album’s songs were decidedly topical, addressing political concerns ranging from integration to the Cuban missile crisis. The first song on the album was “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

“Blowin’ in the Wind” is in three stanzas, each of which concludes with a refrain. Each of the stanzas consists of a series of three questions, the answer to which is promised by the refrain, even though it is never in fact provided. Within each stanza, the questions become increasingly pointed and specific. The first in each set tends to be vague: It does not connect with a social issue and cannot be ascribed specific meaning. The later questions, however, begin to make explicit reference to ongoing political crises. Mentions of “cannon balls” and “deaths” clearly conjure the image of war, while the lament that some people are still not “allowed to be free” elicits scenes of oppression at home and abroad.

However, despite the growing specificity and attendant urgency of the questions, Dylan never makes the subject of his song exactly clear. He is concerned about war, but which war? He laments oppression, but whose? We can easily guess what was on his mind in 1962, when he wrote this song. The Vietnam War, which had been ongoing since 1955, was beginning to attract significant opposition in the United States, while the civil rights movement was quickly gaining momentum. Dylan became particularly involved in the struggle for racial equality. He performed at the 1963 March on Washington, and his third album, The Times They Are a-Changin’ (1963), contained a number of songs that addressed the struggles and victories of equal rights campaigners.

We might, therefore, imagine that we know what this song meant to Dylan, but that does not mean that the significance of “Blowin’ in the Wind” is limited to the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement. Dylan himself ensured that his song could speak to political issues beyond his own time and place. He did so by refraining from mentioning the social causes of his day and instead speaking in broad, almost universal terms. His concerns about war and freedom apply just as well to ancient struggles as they do to those that have yet to take place. We might draw a contrast here with Reece’s song, which explicitly mentions mining and even names one of her adversaries.

Dylan’s music suits his message: Each of the questions begins with the same melodic phrase and ends on an inconclusive pitch, indicating that there is more to be said, while his refrain, which promises an answer, ends on the home pitch (the tonic scale degree). The melody is highly repetitive, making it easy to learn. It also encompasses only a small vocal range and moves almost entirely by step (conjunct motion), making it easy to sing. Finally, the simple guitar accompaniment can be replicated by a moderately competent player. In short, this song, which requires neither special equipment nor advanced musical training, can be performed by almost anyone.

However, Dylan’s melody also carries meaning on a deeper level. Like Reece, he did not write his melody from scratch, but rather adapted it from another song. His source, the African American spiritual “No More Auction Block,” provides us with additional insight into what the song might mean, for “No More Auction Block” describes the relief of a formerly-enslaved person who has escaped from slavery and is no longer to be subjected to humiliations and abuses. According to Alan Lomax, the song originated in Canada, where it was sung by former slaves after the practice was abolished there. It later spread to the United States. Dylan’s melody is not identical, but one can easily hear that he borrowed the opening melodic phrase. When we listen through the lens of the spiritual, we can feel even more confident about the relationship between “Blowin’ in the Wind” and the civil rights movement.

In this recording, we hear Odetta sing the spiritual “No More Auction Block.”

But we can’t go too far in ascribing specific meaning to “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Dylan himself refused to explain what the song meant, or even to admit that it meant anything in particular. When the song was published in Sing Out! magazine in 1962, it was accompanied by the following note from Dylan:

There ain’t too much I can say about this song except that the answer is blowing in the wind. It ain’t in no book or movie or TV show or discussion group. Man, it’s in the wind — and it’s blowing in the wind. Too many of these hip people are telling me where the answer is but oh I won’t believe that. I still say it’s in the wind and just like a restless piece of paper it’s got to come down some … But the only trouble is that no one picks up the answer when it comes down so not too many people get to see and know … and then it flies away. I still say that some of the biggest criminals are those that turn their heads away when they see wrong and know it’s wrong.

In other words, “Blowin’ in the Wind” is about searching for answers, not providing them.

Dylan went even further in distancing his song from the political turmoil of the early 1960s, stating clearly before its first ever performance, “This here ain’t no protest song or anything like that, ‘cause I don’t write no protest songs.” It’s easy to understand why Dylan, an artist with a wide-ranging creative vision, would not want to be pigeonholed as a writer of protest songs. All the same, his claim rings hollow, especially in light of the many activists who were inspired by his song and the social movements that have adopted it.

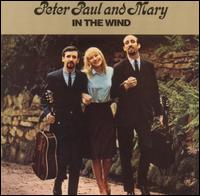

We will examine two recordings of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” both made in 1963. First, we will listen to Bob Dylan’s own version, which was released as a single and included as the lead track on his second album. This version was moderately successful: The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan peaked at 22 on the Billboard album charts. However, Dylan’s songs have almost always done better when sung by other performers. We will also listen to the version by the folk trio Peter, Paul & Mary, who can be considered responsible for making “Blowin’ in the Wind” a hit. Their recording reached number 2 on the Billboard singles charts.

Dylan’s version is remarkably simple and unpolished. He plays a regular rhythm on the guitar, choosing the most obvious chords (he uses only three). At the end of each verse, he pauses to blow a few notes on the harmonica. His timing as a singer was always idiosyncratic, and sometimes the words don’t fall on the beat, as you would expect. His voice is rough, and he doesn’t seem to put any effort into expressing the meaning of the text.

The version recorded by Peter, Paul & Mary is considerably more sophisticated. Although the group also accompanies their singing with guitars, they use two instruments, not one, and the guitars are played using a refined finger-picking style that is far removed from Dylan’s simple strumming. We hear the guitars right at the beginning, when they provide an extended introduction to the song. Peter, Paul & Mary also chose more nuanced and compelling harmonies than Dylan had. As a result, their version is significantly more difficult for an amateur to replicate.

“Blowin’ in the Wind”

Composer: Bob Dylan

Performance: Peter, Paul & Mary (1963)

All three members of the group were singers, and they used this to their advantage by varying the vocal texture phrase by phrase. The first verse begins in two-part harmony with Mary Travers on the melody, but grows in volume and energy when a third voice enters to underscore the final question. Then the men sing the first refrain without Mary, who subsequently sings the first question in the second verse alone. All three take the second question in unison and the third in harmony before Mary sings the second refrain as a solo. The third verse builds to a climax as Mary moves from the melody to a high harmony, after which she sings the final refrain alone. All three provide a final unison refrain to close out the recording. The changes in texture draw the listener’s attention to some of the more important questions (the one about freedom is especially forceful), while also making the song more interesting.

Finally, Peter, Paul & Mary’s version has a polish that is lacking in Dylan’s. The rhythms are regular and predictable, while the voices of the singers are carefully controlled and perfectly in tune. This is not to say that Peter, Paul & Mary’s version is better, and many people prefer Dylan’s recording for its simplicity and honesty. However, this comparison gives us some insight into what makes a hit: It is not only the song that matters, but the arrangement and performance.

Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, “Get Up, Stand Up”

In our previous example, style played an important role in the construction of a successful protest song. On the one hand, the acoustic instruments and simplified techniques of the folk revival made “Blowin’ in the Wind” easy to perform—and also appropriate for informal outdoor renditions in the context of rallies, marches, or picket lines. On the other, the folk style positioned “Blowin’ in the Wind” in a long line of protest songs, of which “Which Side Are You On?” is an early example. In other words, it is typical for a folk song to also be a protest song, and listeners therefore have an easy time accepting “Blowin’ in the Wind” in this role.

Style will also be important to our next example. Some characteristics of the reggae style, which relies on a range of amplified electric instruments, make “Get Up, Stand Up” (1973) somewhat more difficult to use in the context of an on-the-ground protest. At the same time, reggae itself is deeply connected with social rebellion and resistance to oppressive ruling powers—so much so that the genre itself might be considered a protest. In the case of this song, therefore, a knowledge of the reggae style and its historical context is vital to understanding the message of the music.

“Get Up, Stand Up”

Composer: Bob Marley and Peter Tosh

Performance: Bob Marley and the Wailers (1973)

Reggae has been around since 1968, when it emerged as the most widely-performed and influential style of popular music in Jamaica. Reggae represented a synthesis of various music traditions of Central and North America. Jamaican listeners had easy access to American popular music, which was imported on recorded discs and broadcast on the radio, and they were particularly enthusiastic about rhythm ‘n’ blues and jazz. Following Jamaican independence in 1962, however, Jamaicans were increasingly interested in developing unique popular music styles that represented their national identity. The first of these were ska (an uptempo style featuring jazz instrumentation and off-beat accents) and rocksteady (a slower version of ska), both of which influenced reggae. Ska and rocksteady also drew from the Caribbean traditions of mento and calypso—as did reggae in its own turn.

The meaning of the Jamaican English term “reggae” has been much debated. It can be used to refer to a person who is poorly dressed, or to a quarrel. It has also been connected with the term “streggae,” which can describe a loose woman. The term was first used in a musical context in the Maytals’s 1968 song “Do the Reggay,” which also established the stylistic conventions of what would become a major new genre. The lead singer of the group, Frederick “Toots” Hibbert, provided his own definition of the term: “Reggae just mean comin’ from the people, an everyday thing, like from the ghetto. When you say reggae you mean regular, majority. And when you say reggae it means poverty, suffering, Rastafari, everything in the ghetto. It’s music from the rebels, people who don’t have what they want.” Reggae music, therefore, would speak to regular Jamaicans, and it would address their rebellious desire to overthrow the forces that kept them in poverty.

Hibbert also mentions Rastafarianism, which is another vital ingredient to reggae. We can understand neither the reggae worldview nor the specific lyrics of reggae songs without addressing this movement. Rastafarianism can trace its roots to the “Back to Africa” movement of the 1920s. The leader of the movement was Marcus Garvey, a firey political orator of Jamaican origin who advocated for pan-African unity. In his view, those of African descent in all parts of the world should take pride in their heritage and throw off the yoke of white colonial oppression. He sought independence for black majority colonial states but also encouraged members of the African diaspora to return to Africa, where he imagined the founding of a single unified African state with himself at the head. While organizing in the United States, Garvey went so far as to establish a shipping company, the Black Star Line, for the express purpose of returning African Americans to the African continent. This project, however, led to Garvey’s 1923 conviction for mail fraud, after which he was deported.

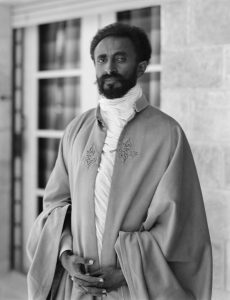

Back in Jamaica, Garvey prophesied that the liberation of the entire African diaspora would be sparked by the crowning of a black king in Africa. He founded his claim in an interpretation of the Book of Revelation, which foretells the rise of the Lion of Judah. When the Ethiopian regent Ras Tafari Makonnen became Emperor Haile Selassie I in 1930, therefore, Garvey and others believed that the prophecy had been fulfilled. Selassie, whose full title includes the designation “Lion of the Tribe of Judah,” traced his own lineage back to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

Selassie himself was an Ethiopian Orthodox Christian, and he disdained the prophecies that were emanating from the New World. In Jamaica, however, Selassie’s coronation sparked a wave of renewed black pride and confidence that the end of colonial oppression must be at hand. Selassie’s former title and name soon lent itself to the new movement, which was part political ideology and part religion.

Rastafarians adhere to the teachings of the Bible, which they believe to have originally been written in an Ethiopian language. They reject colonial domination and seek to recover a shared black identity. However, there is no centralized authority within the Rastafarian community, and there are no administrative hierarchies or orthodox beliefs. Rastafarians are not even agreed about the identity of Emperor Haile Selassie: Some believe that he is Christ reincarnate, while others regard him as a prophet. (The fact that Selassie was assassinated in 1974 led some to lose their faith, but devout followers maintained either that his death had been faked or that he survived in a spiritual form.)

Despite the negligible status of Rastafarianism as a religion (there are at most one million practitioners around the world), it has attracted significant attention due to the popular success of reggae music. Many Jamaican musicians of the 1960s found themselves drawn to the ideology, and reggae music soon came to embody Rastafarian identity and beliefs. Rastafarians were also quick to establish a wide variety of symbols—the green, yellow, and red colors of the Ethiopian flag, dreadlocks, and cannabis use—that helped identify practitioners to the larger community. All of these symbols came to be associated with reggae as well. When reggae gained popularity abroad following the success of the 1973 film The Harder They Come, a wide variety of cultural symbols were therefore available for use in identifying and promoting the new musical style.

For most people, it is the sound of reggae music that initially attracts them to the genre. All reggae songs have a moderate, laid-back tempo. They are in quadruple meter, but the emphasis is on the off-beat, which is usually marked by two sharply articulated strums on the electric guitar. The bass also plays an important role, accentuating strong beats and contributing countermelodies, while the drums hold the groove in place. Other typical instruments include the electric organ, which often fulfills a similar role to that of the guitar, and jazz-derived horns including the saxophone and trumpet.

The rhythms in reggae emerge from the interactions of these various instruments, each of which contributes one element to a complex groove. No single instrument is responsible for the rhythmic character of a song, but each has a unique role in sustaining the beat. At the same time, individual players are free to vary their rhythms, the result of which is a flexible groove that shifts in form while maintaining its essential identity. In reggae, various rhythmic patterns—termed “riddims”—have specific names and coded meanings, known only to those initiated into the tradition. The essential structure of the rhythmic texture, however, is derived from African practices and can be found in various musical traditions of the African diaspora.

We will hear this type of groove in our recording of “Get Up, Stand Up.” Before considering the sound the the song, however, we must address the lyrics. The message of “Get Up, Stand Up” is embodied in its short chorus, which calls on the listener to “stand up for your rights,” with the added encouragement, “don’t give up the fight!” All three verses also conclude with the “stand up for your rights” refrain, which echoes both the text and music of the chorus.

While the chorus and concluding refrains are unambiguous, the three verses contain references to the Rastafarian belief system that might be lost on the uninitiated. The first verse opens with a derisive reference to a “preacher man,” who symbolizes the institutionalized (and white) Christian church, which Rastafarians regard as an oppressive force. It continues on to warn that “not all that glitters is gold,” a reflection of the Rastafarian disdain for worldly possessions. The second verse mocks those who await the second coming of Christ, while the third makes the observation that “almighty Jah is a living man”—both expressions that rest on the common Rastafarian belief that Emperor Haile Selassie is (or was) God incarnate.

In sum, therefore, “Get Up, Stand Up” is a song steeped in the Rastafarian tradition that calls for the listener to pursue both spiritual and political freedom. The call to protest embodied in its chorus is broad and might be applied to any number of specific situations. The verses, however, outline a uniquely Rastafarian worldview that few listeners are likely to accept. In this way, “Get Up, Stand Up” might be considered a deeply flawed protest song, for it seems to be intimately tied to the time and place of its origin. While “Blowin’ in the Wind” could be about any war or any oppressive situation, “Get Up, Stand Up” is explicitly about the Jamaican experience.

The creators of “Get Up, Stand Up,” however, would not have seen this specificity as a flaw. They were committed to giving voice to the oppressed among the African diaspora, and they couldn’t care less about whether their song could be conveniently exploited by others. “Get Up, Stand Up” was the creation of two of reggae’s chief architects, Bob Marley (1945-1981) and Peter Tosh (1944-1987). The song was initially inspired by the suffering of impoverished Haitians, whose condition Marley witnessed when touring the island in the early 1970s. Marley recorded several versions of the song with his group, The Wailers, while Tosh released his own solo version. We will consider the first recording of “Get Up, Stand Up,” which appeared on The Wailers’ 1973 album Burnin’.

The track begins with a few drum hits, after which the basic pulse is established by various electric guitars. The groove—with all of its parts in place—enters along with Marley’s voice. Although most of the instruments in the band are occupied with the groove, a guitar—the sound of which is processed by a “wah-wah” pedal—occasionally interjects melodic riffs, while an electric bass periodically fills in between sung phrases. Marley’s voice is recorded on several tracks, which allows him to converse with himself in a call-and-response style: While one Marley sings the chorus, another provides encouragement. His informal yet impassioned vocal delivery is meant to connect emotionally with the listener and spur them into action. The idea of collectivity is reinforced by double-tracking on the chorus. Because we actually hear more than one voice singing the call to protest, we easily imagine a crowd—and just as easily join in ourselves. The chorus, after all, is very easy to sing. It contains only four pitches, and the melody outlines the stepwise ascent of a scale.

The harmonies, likewise, are easy to play. The entire song essentially rests on a single minor triad—a harmony that reinforces the seriousness of the song’s message, and that literally anyone could provide using a guitar or piano. Here, however, we run into some difficulty, for while it is easy to replicate the harmony and melody of the chorus to “Get Up, Stand Up,” it is very difficult to replicate the style. To do so requires a broad array of electric instruments, each played by an expert with perfect timing and a deep knowledge of their role in the groove. This can only be accomplished in a staged setting. While Peter Yarrow was able to strum his guitar and lead a sing-along of “Blowin’ in the Wind” at a 2011 Occupy Wall Street protest, for example, “Get Up, Stand Up” is more likely to be blasted over loudspeakers, as it was during the 2011 teachers’ strike in Madison, WI.

In this video, we see Peter Yarrow leading a sing-along of “Blowin’ in the Wind” at a 2011 Occupy Wall Street protest.

In this video, a recording of “Get Up, Stand Up” is played at the 2011 teachers’ strike in Madison, WI.

Resources

Print

Hevener, John W. Which Side Are You On?: The Harlan County Coal Miners, 1931-1939. University of Illinois Press, 2002.

Hilburn, Robert. Paul Simon: The Life. Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Kasper, Eric T., and Benjamin Schoening, eds. You Shook Me All Campaign Long: Music in the 2016 Presidential Election and Beyond. University of North Texas, 2018.

McDougal, Dennis. Dylan: The Biography. Wiley, 2014.

Schoening, Benjamin, and Eric T. Kasper. Don’t Stop Thinking About the Music: The Politics of Songs and Musicians in Presidential Campaigns. Lexington Books, 2011.

Taruskin, Richard. Music in the Early Twentieth Century: The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Turino, Thomas. Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. University of Chicago Press, 2008.

White, Timothy. Catch a Fire: The Life of Bob Marley. Holt Paperbacks, 2006.

Yurchenco, Henrietta. “Trouble in the Mines: A History in Song and Story by Women of Appalachia.” American Music, Vol. 9, No. 2 (1991): 209-224.

Zanes, Warren. Petty: The Biography. Griffin, 2016.

Online

Trax on the Trail: http://www.traxonthetrail.com/

Dana Gorzelany-Mostak et al., “Making Trax in 2016 and Beyond,” Bulletin of the Society for American Music, Volume XLIV, No. 3 (Fall 2018): https://www.american-music.org/general/custom.asp?page=Bulletin443Fall2018

NPR, “‘A Song For Any Struggle’: Tom Petty’s ‘I Won’t Back Down’ Is An Anthem Of Resolve”: https://www.npr.org/transcripts/721228788?storyId=721228788?storyId=721228788