Unit 2: Music for Storytelling

6 Stories without Words

Esther M. Morgan-Ellis and Ross Hagen

Over the course of the past three chapters, we have examined a variety of musical forms and works that communicate narratives. These have included examples that rely on staged action, such as opera and ballet, and examples that incorporate a sung text. In this chapter, we will encounter music that tells a story without that aid of staged action or performed text. This music will use sound alone—perhaps supplemented by a written explanation—to communicate with the listener.

But how can sound tell a story? How can we know what music is about without seeing the story acted out or hearing the story told through words? In many ways, music is handicapped as a storytelling medium, for it cannot be specific. Sound cannot tell us the name of a character, or provide details about a dramatic setting, or convey dialogue, or even communicate a plot of any complexity. At the same time, sound can also be a particularly powerful storytelling medium. Because of its potential to provoke emotions in the listener, it can tell compelling stories on the emotional or psychological level. Music can also incorporate the sounds that would be heard in a specific setting or that might accompany a sequence of events, thereby recreating the aural experience of a story.

In general, music is able to communicate specific content using three techniques. While these have been primarily exploited in the European concert tradition, they are not unique to Western music. The three techniques are mimesis, quotation, and the use of musical topics. After an introduction to each in turn, we will see them at work in a variety of examples.

Mimesis is the simplest technique, and also the most common across traditions. In cases of mimesis, music imitates real-world sounds in order to call elements of the physical world to mind. These sounds might include birdsong, animal cries, trains, explosions, footsteps—anything that makes noise. Mimesis can be used to create a dramatic scene using sound alone.

In the case of quotation, one piece of music incorporates a passage from another. Quotation can be used in many different ways. Sometimes, the quoted music will have a text that the listener is expected to know. In this way, a composer can include specific dramatic content without employing text directly. Other times, the quoted music can be understood as part of a scene. For example, the American composer Charles Ives quoted the music of Wagner in his piano composition Concord Sonata. His intent was to recreate the living room of the Alcott family, with Louisa May playing her favorite tunes at the piano.

When a composer employs musical topics, they refer to recognizable musical styles or clichés in order to communicate with the listener. Some musical topics are associated with specific genres or traditions, such as military marches, waltzes, or Christian hymns. Upon hearing one of these styles referenced in a musical work, the listener might think of an army, or a ball, or a church service. In this way, the composer can transport an audience to a specific place.

Other musical topics rely on the use of standardized techniques to portray specific scenes, such as a storm, or a romantic tryst, or shepherds tending their flocks. This approach builds on the tradition of music for the theater. An operatic love scene, for example, is usually accompanied by slow, sweeping gestures in the strings, while shepherds appear to the accompaniment of droning bagpipes (usually imitated by orchestral instruments), flute, and double reeds (usually oboe or English horn). Musical topics often incorporate mimesis, although the technique is more complex. Hunting scenes, for example, were long set to music that used mimetic techniques to imitate the sounds of horses galloping and hunting horns blasting. The imitation of hoofbeats is an example of mimesis, but the hunting topic is associated not only with the sounds of hunting but also with the tradition of writing hunting music. The storm topic provides a similar example. While rapid chromatic scales, dynamic swells, and sudden accents can imitate wind blowing through the trees and lightning striking the ground, we recognize storm music primarily because we are familiar with the long tradition of this type of music being used to accompany storm scenes in opera, films, and cartoons.

In the European tradition, instrumental music that claims to tell a specific story or to otherwise communicate extramusical information is termed program music. This term was first employed in the 19th century, at which point in history a fierce debate took place between various European composers and critics concerning the purpose of music. Some argued in favor of program music, even going so far as to suggest that music could (and should) convey complex philosophical ideas. Wagner belonged to this school of thought. Others advocated on behalf of absolute music, or “music for music’s sake”—that is, music that does not aspire to be more than sound, and that should be judged on the basis of its form and construction, not its power to communicate. Even in the 19th century, however, program music was not a new thing. As we shall see, earlier European composers had already established the various techniques with which music can communicate meaning. Similarly, composers and performers in other parts of the globe had long exploited sound as a storytelling vehicle.

We will begin, however, in 19th century Europe, with perhaps the most famous piece of program music to emerge from the concert tradition.

Hector Berlioz, Fantastical Symphony

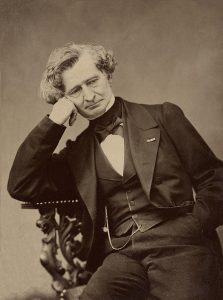

When the French composer Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) premiered what was to be his most famous and influential work, he was only 27 years old. 1830, however, was a big year for the young composer. Not only was his Fantastical Symphony (French: Symphonie Fantastique) premiered in December at the Paris Conservatory, but he also won the Rome Prize (French: Prix de Rome), the top honor for French composers.

However, Berlioz’s training as a composer had been largely self-directed. His father had intended for him to become a physician, and it was to study medicine at the University of Paris that he had first moved to the city. Berlioz completed medical school, despite his disgust at the task of dissecting dead bodies, but he continued to pursue his musical interests throughout the course of his professional education. He gave up medicine upon graduating in 1824 and enrolled in the Paris Conservatory two years later.

During the Romantic era (roughly 1815 to 1900), audiences were fascinated by the personal lives of artists. They tended to understand artistic expression as autobiographical, and they perceived works through the lens of an artist’s personal experience. In the case of Fantastical Symphony this was easy to do, for Berlioz was directly inspired by his own real-world experiences. Before discussing the symphony, therefore, we must dedicate some attention to Berlioz’s love life.

The Origins of Berlioz’s Symphony

In 1827, Berlioz attended a series of Shakespearean performances put on in Paris by a company of Irish actors. Over the course of several plays, he became obsessed with the actress Harriet Smithson, whom he saw in the roles of Ophelia (Hamlet) and Juliet (Romeo and Juliet). His subsequent behavior, which included moving into an apartment from which he could monitor her own dwelling and subjecting her to a deluge of correspondence, can only be described as stalking. She ignored his advances, however, and returned to London in 1829 without ever having met the composer.

Despite never so much as speaking to Harriet, Berlioz felt compelled to channel his passion into musical composition. He let it be widely known that Fantastical Symphony, which tells the story of a romantic obsession gone wrong (details later), was about Harriet Smithson.

Berlioz’s romantic interests were intense but fleeting. He soon recovered from his infatuation with Smithson and in 1830 became engaged to Marie Moke. His status as the winner of the Rome Prize required that he spend several years studying composition in Italy, and while he was abroad he received word from Marie’s mother that she was going to marry the wealthy piano manufacturer Camille Pleyel instead. Berlioz flew into a rage. He purchased guns, poison, and a costume, and boarded a train for Paris with the intention of sneaking into the Moke home dressed as a woman and murdering mother, daughter, and fiance before taking his own life. During the course of the trip, however, his passion cooled, and he abandoned the plan before arriving in Paris. He returned to Italy to complete the terms of his award.

Then, in 1832, Harriet Smithson found herself back in Paris. Berlioz saw that she was provided with a ticket to the premiere of his second symphony, entitled The Return to Life and conceived of as a sequel to Fantastical Symphony. She wrote him a letter complimenting the symphony and the two finally met. They began an affair and married in 1833, although it is widely suspected that Smithson only agreed to the union because of her dire financial situation. The two were not happy, and formally separated in 1843.

In the case of another composer, the above personal details might be gratuitous. In the case of Berlioz, however, they are essential. Not only did his audiences know about his love life, but they relished the opportunity to perceive his music as a window into his most intimate passions. Of course, Fantastical Symphony was not altogether autobiographical. In fact, most of the story, to which we will turn now, was lifted from books that Berlioz was reading at the time.

Berlioz went to great trouble to create, revise, and publicize the story told by his music. He published several versions, the last of which accompanied the 1855 version of the score. It was important to Berlioz that audiences were familiar with the story. For the 1830 premiere, he saw that his narrative was published in Parisian newspapers and distributed to audience members at the performance. (At this time, it was unusual for concert patrons to be provided with a printed program.) In the 1845 version of the score, Berlioz explained the importance of his narrative: “The following programme must therefore be considered as the spoken text of an opera, which serves to introduce musical movements and to motivate their character and expression.” In short, he did not seem to believe that the music could speak entirely for itself.

The Structure and Story of Fantastical Symphony

Berlioz subtitled his Fantastical Symphony “An Episode in the Life of an Artist, in Five Parts.” The artist in question was, of course, himself. The five parts were five distinct movements—an unusual design for a symphony. While most symphonies have four movements, Berlioz was self-consciously following in the footsteps of Ludwig van Beethoven, whose only program symphony—his Symphony No. 6 “Pastoral”—also had five movements. Beethoven’s symphony told the story of a visit to the countryside, but it did so in very vague terms. The only texts were the five movement titles, which described the sensation of peace upon arriving in nature, a scene by a brook, a peasant festival, a thunderstorm, and feelings of relief after the storm had passed. To tell his story, Beethoven deployed musical topics associated with the countryside and incorporated mimetic gestures, including orchestral imitations of droning bagpipes and violent lightning strikes. Berlioz used the same techniques, but took the idea of writing a program symphony much further.

Berlioz’s five movements are entitled “Reveries—Passions,” “A Ball,” “Scene in the Fields,” “March to the Scaffold,” and “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath.” In the first movement, a young musician catches sight of his ideal woman and immediately falls in love with her. We learn from Berlioz’s text that the musician always hears the same melody in his head when he sees or thinks of her—a melody “in which he recognizes a certain quality of passion, but endowed with the nobility and shyness which he credits to the object of his love.” Berlioz termed this melody the “obsession” (French: idée fixe).

The obsession melody returns in each of the five movements. In the second movement, we hear it when the protagonist glimpses the object of his affection at a ball. In the third movement, the protagonist sits alone in the countryside, listening to shepherds play their pipes. At first he feels hopeful about the future, but he is soon overwhelmed with suspicion and foreboding. The obsession melody reveals the subject of his disturbed brooding.

Because we will examine the fourth and fifth movement in detail, it is worth reading Berlioz’s original description of each in full. His text to accompany the fourth movement reads as follows:

Convinced that his love is spurned, the artist poisons himself with opium. The dose of narcotic, while too weak to cause his death, plunges him into a heavy sleep accompanied by the strangest of visions. He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned, led to the scaffold and is witnessing his own execution. The procession advances to the sound of a march that is sometimes sombre and wild, and sometimes brilliant and solemn, in which a dull sound of heavy footsteps follows without transition the loudest outbursts. At the end of the march, the first four bars of the idée fixe reappear like a final thought of love interrupted by the fatal blow.

It is here that we begin to depart notably from reality. Although Berlioz was indeed an opium user, as evidenced by letters that he wrote to his father in 1829 and 1830, it seems likely that his ideas for this movement came primarily from a book he was reading, Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-

Eater (1821).

March to the Scaffold

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | “The procession advances to the sound of a march…” | A rhythmic pattern played on the timpani sets the scene for a procession. |

| 0’28” | “…that is sometimes sombre and wild, …” [March theme A] |

This theme, on which we hear many variations, consists of a descending scale with a brief ascending motif at the end. |

| 1’40” | “…and sometimes brilliant and solemn” [March theme B] |

This theme, which is considerably louder and more triumphant, features the brass playing dotted rhythms. |

| 2’11” | March theme A |

The A theme returns briefly, played by the strings and woodwinds in an interlocking texture. |

| 2’22” | March theme B |

The B theme returns, this time with an active string accompaniment. |

| 2’52” | March theme A |

The A theme returns as it did before. |

| 3’00” | The low brass play the descending scale of the A theme repeatedly at successively higher pitch levels, thereby building intensity. | |

| 3’14” | The entire orchestra plays the A theme, first in its natural form and then upside down (an ascending scale). | |

| 3’40” | Coda | We hear a new theme at a faster tempo. |

| 4’17” | “…the first four bars of the idée fixe reappear like a final thought of love…” |

We hear the obsession melody in the solo clarinet. |

| 4’26” | “…interrupted by the fatal blow.” |

The melody is cut off by a resounding chord, symbolizing the fall of the guillotine blade; triumphant chords from the brass represent the cheers of the crowd. |

“March to the Scaffold” exhibits all three of the communication techniques outlined above: mimesis, quotation, and the use of musical topics. For most of the movement, we hear two contrasting march themes, one (according to Berlioz’s description) “sombre and wild” and the other “brilliant and solemn.” These themes exemplify the use of musical topics. We are able to recognize them immediately as marches due to the tempo, the brisk character, and the instrumentation, which features percussion and brass. In the final passage of the movement, the tempo accelerates and the excitement builds. Then, out of nowhere, we hear the obsession melody played on a solo clarinet. This, of course, is an example of quotation. We are familiar with this melody and we know that it represents the protagonist’s beloved. We can easily hear it, therefore, as his final thought of her. Before the melody can conclude, a great noise from the orchestra represents the guillotine blade crashing down. This is followed by two pizzicato “bounces” of the severed head and a series of raucous “cheers” from the crowd. All of this is mimesis, for Berlioz uses the orchestra to represent the sounds of the scene he is portraying.

“March to the Scaffold” was the most successful of the symphony’s five movements, and it was frequently programmed as a standalone work during Berlioz’s lifetime. However, the final movement, “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath,” offers even better examples of our three communication strategies. It is also shows off Berlioz’s extraordinary skill at using the orchestra. The music of Berlioz is still studied today by students of orchestration, and his 1843 Treatise on Instrumentation is still in print. He was also responsible for growing the orchestra in size. Although he wanted 220 musicians for the premiere of Fantastical Symphony, he had to settle for a mere 130. In addition to increasing the size of the string sections, Berlioz increased the number of required wind parts. Fantastical Symphony calls for four different types of clarinets, four bassoons, four harps, and an enormous percussion section, in addition to two instruments—the ophicleide (part of the tuba family) and the cornet à pistons (part of the trumpet family)—that were not typically included in the symphony orchestra. The final movement of Fantastical Symphony makes the most dramatic use of this extensive orchestral palette.

Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | “Strange sounds, …” | Tremolo in the violins and violas. |

| 0’03” | “…groans, …” | Upward sweeps in the cellos and basses. |

| 0’17” | “…outbursts of laughter; …” | Chromatic descent in the violins and violas. |

| 0’32” | “…distant shouts which seem to be answered by more shouts.” | Call and response between woodwinds and a muted horn. |

| 0’53” | All of the preceding material is repeated, with some variations. | |

| 1’37” | “The beloved melody appears once more, but has now lost its noble and shy character; it is now no more than a vulgar dance tune, trivial and grotesque” | We hear the opening of the obsession melody in the clarinet; it is played at a fast tempo with an uneven, dance-like rhythm |

| 1’46” | “Roar of delight at her arrival” | The brass enter at top volume. |

| 1’58” | “She joins the diabolical orgy” | We hear the entire obsession melody in the high-pitched E-flat clarinet, accompanied primarily by double reeds. |

| 3’11” | “The funeral knell tolls…” | The orchestra bells sound the tolling of the knell. |

| 3’39” | “…burlesque parody of the Dies irae…” | The opening phrase of the “Dies irae” melody is heard, first in the low brass, then in the trombones at twice the tempo, and finally in the woodwinds and pizzicato strings at twice the tempo again. |

| 4’18” | The second phrase of the “Dies irae” melody undergoes similar treatment. | |

| 4’42” | The third phrase of the “Dies irae” melody undergoes similar treatment. | |

| 5’20” | “…the dance of the witches…” | A new theme emerges in the strings. |

| 5’38” | The new theme, which we recognize as “the dance of the witches,” is presented first in the cellos, then the violins, then in the woodwinds. | |

| 7’28” | A hint of the “Dies irae” melody return in the cellos and basses; the other strings play fragments of “the dance of the witches.” | |

| 8’34” | “The dance of the witches combined with the Dies irae.” | We hear complete statements of both melodies layered atop one another, “Dies irae” in the brass and “the dance of the witches” in the strings. |

Berlioz explained the action in “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath” as follows:

He sees himself at a witches’ sabbath, in the midst of a hideous gathering of shades, sorcerers and monsters of every kind who have come together for his funeral. Strange sounds, groans, outbursts of laughter; distant shouts which seem to be answered by more shouts. The beloved melody appears once more, but has now lost its noble and shy character; it is now no more than a vulgar dance tune, trivial and grotesque: it is she who is coming to the sabbath… Roar of delight at her arrival… She joins the diabolical orgy… The funeral knell tolls, burlesque parody of the Dies irae, the dance of the witches. The dance of the witches combined with the Dies irae.

The movement opens exactly as Berlioz describes, with “strange sounds, groans, outbursts of laughter.” Strange sounds are certainly heard in the violins. The players employ a technique known as tremolo, in which the bow is moved back and forth very quickly to produce a shaking effect. The cellos undeniably provide the groans, with their quick upward melodic sweeps. Both the violins and trombones can later be heard as laughing. Next we hear “distant shouts” in the high winds, echoed by “more shouts” from a muted horn. The opening passage, therefore, is constructed almost exclusively with the use of mimetic techniques.

When the obsession melody returns, it has indeed transformed in character. It is now a lively, impish dance tune played on the E-flat clarinet—an uncommon, high-pitched version of the instrument with a piercing sound quality. The tune is at first interrupted by a mimetic “roar of delight” from the orchestra, after which it is heard in full. In this case, quotation is combined with the use of a musical topic. We recognize the melody and understand what it represents, but the fact that it is presented as a dance tune adds meaning to its appearance.

After the dance dies away we hear the funeral bells. This barely even counts as mimesis, since Berlioz calls for actual bells to be struck. (He uses the tubular orchestra bells that are included in a standard large percussion section.) Next he employs a second quotation. This time he quotes a melody from outside the symphony—indeed, it is a melody that was composed more than 500 years before Berlioz was even born!

The “Dies irae” comes from the body of medieval Catholic church music known as Gregorian chant. This particular chant was composed in the 13th century and was associated with the funeral Mass, or Requiem. It was sung at the graveside and contains a particularly ominous text. The first three lines read as follows:

A day of wrath; that day,

it will dissolve the world into glowing ashes,

as attested by David together with the Sibyl.

What trembling will there be,

when the Judge shall come

to examine everything in strict justice.

The trumpet’s wondrous call sounding abroad

in tombs throughout the world

shall drive everybody forward to the throne.

The long text continues on to describe the coming of Judgment Day, when sinners are cast into Hell to endure eternal torment. Berlioz’s audience in Catholic France would have recognized this melody immediately, and would likewise have known the associated text. For them, the “Dies irae” carried connotations of terror and hellishness. By using it in his symphony, therefore, Berlioz was able to take advantage of those connotations without incorporating text directly. The “Dies irae” provided the perfect backdrop for his triumphant witches.

Next Berlioz incorporates another dance topic, named in his synopsis as the “dance of the witches.” We don’t recognize the melody itself, but we have no trouble acknowledging that it is a dance, and Berlioz’s description helps us to understand exactly what it going on. Finally, before the raucous conclusion, we hear the “Dies irae” and the “dance of the witches” juxtaposed, each sounding at the same time in a different part of the orchestra. The concluding passage also includes more unusual string techniques, including col legno (with wood), for which players turn their bows over and bounce the stick on their strings. This creates an eerie tapping effect.

Antonio Vivaldi, The Four Seasons, “Spring”

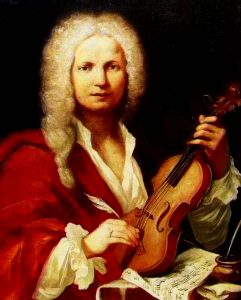

Composers were writing program music long before Berlioz. In earlier periods, however, such compositions were generally perceived as entertaining novelties, not the future of concert art. The Italian violinist and composer Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) was particularly fond of program music, and he produced a great deal. His set of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons (Italian: Le quattro stagioni, 1725) are the most famous. Indeed, they rank among the best known pieces of music from the European concert tradition.

Vivaldi’s Career

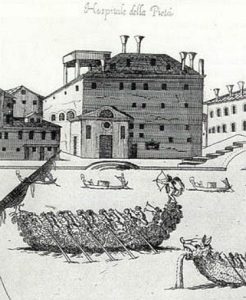

Vivaldi spent his life in the city of Venice, which at the time was a wealthy and independent Republic. He initially trained as a Catholic priest, but ill health prevented him from performing many of his duties. However, he became highly skilled as a violinist and composer, and in 1703 he took the position of violin master at a local orphanage, the Devout Hospital of Mercy (Italian: Ospedale della Pietà; note that Hospital at this time does not indicate a center for medical care).

Venetian orphanages were not the squalid workhouses we know from Victorian literature. Indeed, quite the opposite. It was common—even acceptable—for Venetian aristocrats to keep mistresses, but the children of these relationships could not be brought up in the marital home. Instead, unwanted infants were deposited at orphanages via the scaffetta, which was an opening just large enough to fit a newborn. While not all of the surrendered infants were of high birth, the city’s noblemen took an interest in the welfare of their illegitimate children, which meant that the orphanages were always well-funded. The children were brought up with all of the advantages (except parents), and were prepared for comfortable lives.

The Devout Hospital of Mercy, at which Vivaldi took a position, was an orphanage for girls. His job was to teach them the musical skills that would allow them to secure desirable husbands. Vivaldi was exceptionally good at his job, and soon the girls at the orphanage became the best musicians in the city. He not only taught them how to play their instruments but wrote music for them to play. His primary vehicle was the concerto, which is a work for an instrumental soloist accompanied by an orchestra. Over the course of his career, Vivaldi wrote 500 concertos. About half were for violin, including 37 for his most successful protege, a virtuoso known as Anna Maria dal Violin. The other were mostly for bassoon, flute, oboe, and cello—all instruments played by girls at the Hospital.

Naturally enough, the citizens of Venice wanted to hear the girls perform. This, however, presented a serious problem. Women in Venetian society were generally prohibited from performing publicly. Some women took to the opera stage, but in doing so they were confirming their sexual availability and precluding the possibility of marriage. Most of the girls at the orphanage were destined for either husbands or a lifetime of service to the church, so they could not become soiled in this way. Those who did desire a career in music were likely to stay at the orphanage into adulthood, where they were provided with an opportunity to teach and perform. At least two girls who studied at the orphanage, Anna Bon and Vincenta Da Ponte, went on to become composers.

The orphanage developed a clever means by which to facilitate public performances without upsetting social convention. Each Sunday night, a public Vespers service was held for which the orchestra and choir provided music. Although this weekly church service was, for all intents and purposes, a public concert, the simple act of retitling protected the girls’ honor. Members of high society came from across the region to hear the girls, who were physically isolated from the visitors to further ensure their chastity.

Vivaldi was promoted to music director in 1716, and he continued to teach at the orphanage even as he became quite famous outside of Venice. In addition to writing instrumental music, he wrote operas that were staged across Europe and provided choral music for Catholic church services. His long tenure at the orphanage was noteworthy, for male teachers at girls’ orphanages usually got into trouble with one of their charges and eventually had to be dismissed. Vivaldi, on the other hand, developed a reputation for his ethical behavior.

For Vivaldi, the concerto was a relatively new genre. The first concertos had been written by Italian composers in the middle of the 17th century. At first, soloists were used primarily to add variation in volume to an orchestral performance—after all, a few players make less noise than many, and individual string instruments of the time did not have a large dynamic range. Vivaldi still valued the potential for concertos to include a great deal of variety, but he also used them as a vehicle for virtuosic display. The solo parts, therefore, were often quite difficult, and allowed the player to show off her capabilities.

An early 18th-century concerto always followed the same basic form. It would contain three movements in the order fast-slow-fast. The outer movements would both be in ritornello form. “Ritornello” is an Italian term that roughly translates to “the little thing that returns,” and it refers to a passage of music that is heard repeatedly. In a concerto, the ritornello is played by the orchestra. It is heard at the beginning and at the end of a movement, but also frequently throughout, although often not in its entirety. In between statements of the ritornello, the soloist plays. Although the ritornello always remains basically the same, the material played by the soloist can vary widely. The slow movement of a concerto would consist of an expressive melody in the solo instrument backed up by a repetitive accompaniment in the orchestra.

Spring

We will see an example of these forms in Vivaldi’s “Spring” concerto. However, form is certainly not what makes this composition interesting. Vivaldi published his Four Seasons concertos in a 1725 collection entitled The Contest Between Harmony and Invention. This evocative title was supposed to draw attention to novel aspects of Vivaldi’s latest work. While eight of the twelve concertos contained in the collection were adventurous in purely musical terms, the first four were unusual for programmatic reasons.

Each of the Four Seasons concertos—one each for Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter—was accompanied by a sonnet. The poetry described the dramatic content of the music, and Vivaldi went to great trouble to indicate exactly how the music reflected the text. To do so, he inserted letter names beside each line of poetry and then placed the same letter at the appropriate place in the score. The correlation between musical and poetic passages, however, is easy to hear. This, in combination with the fact that no author is indicated, has led most scholars to believe that Vivaldi wrote the sonnets himself.

The sonnet for the “Spring” concerto reads as follows. The lines of poetry are broken up between the three movements, each of which is titled with an Italian tempo marking:

I. Allegro

Springtime is upon us.

The birds celebrate her return with festive song,

and murmuring streams are

softly caressed by the breezes.

Thunderstorms, those heralds of Spring, roar,

casting their dark mantle over heaven,

Then they die away to silence,

and the birds take up their charming songs once more.

II. Largo

On the flower-strewn meadow, with leafy branches

rustling overhead, the goat-herd sleeps,

his faithful dog beside him.

III. Allegro

Led by the festive sound of rustic bagpipes,

nymphs and shepherds lightly dance

beneath the brilliant canopy of spring.

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | Ritornello – “Springtime is upon us.” | The ritornello has an internal form of aabb; its simplicity and repetition suggest a folk dance. |

| 0’29” | A – “The birds celebrate her return with festive song, …” | The solo violinist and two violinists from the orchestra join together in imitation of birdsong. |

| 1’03” | Ritornello | The ritornello is slightly abbreviated in this and all future appearances. |

| 1’10” | B – “…and murmering streams are softly caressed by the breezes.” | The entire orchestra plays repetitive figures that rise and fall, imitating the murmur of the stream. |

| 1’33” | Ritornello | |

| 1’40” | C – “Thunderstorms, those heralds of Spring, roar, casting their dark matle over heaven,…” | The orchestra imitates thunder with low-range tremolo and lightning with quick ascending scales; the solo violinist shows off their virtuosity with rapid arpeggios. |

| 2’08” | Ritornello | This ritornello is in the minor mode. |

| 2’16” | D – “Then they die away to silence, and the birds take up their charming songs once more.” | The solo violinist slowly ascends using repeated notes, suggesting calmness; the section ends with trills in the the violins, another imitation of birdsong. |

| 2’32” | Ritornello | This ritornello is the least stable, as it moves from one key to another. |

| 2’42” | E | This solo does not correspond with a passage of poetry; its sole function is to prepare the final ritornello. |

| 2’56” | Ritornello | The last thing we hear is the bb section of the ritornello. |

The opening ritornello in the first movement captures the spirit of the first line of poetry. It is joyful and exuberant. It is also simple and repetitive, giving the impression that it might really be folk music—the kind of tune one might hear at a country dance. The birds appear with the first solo episode, which requires two violinists from the orchestra to join with the soloist in imitating avian calls. After an orchestral ritornello, we hear some new music from the orchestra that captures the sounds of murmuring streams and caressing breezes. Another ritornello is followed by the thunderstorm. Rapid notes, sudden accents, and violent ascending scales in the orchestra are interrupted by energetic arpeggios in the solo violin, while shifts to the minor mode darken the mood of the passage. After another ritornello, the bird songs gradually reemerge, gaining strength as the storm clears for good. One more solo passage and a final ritornello close out the movement.

The second movement is considerably simpler. The solo violin plays a beautiful, calm melody—suitable for the portrayal of a sleeping goat-herd. Underneath, the leafy branches rustle in the violins, who play undulating, uneven rhythms throughout, while the faithful dog barks in the violas. (This last touch is a little strange, for a barking dog would certainly wake the sleeper, but Vivaldi did not have any other tools with which to represent the animal.) The fact that no low strings or harpsichord are present in this movement gives it an ethereal feeling.

“Spring,” Movement II

Composer: Antonio Vivaldi

Performance: Takako Nishizaki with the Shanghai Conservatory Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Cheng-wu Fan (2000)

The last movement has the same form as the first, although the storytelling is considerably less intricate. In the opening ritornello, Vivaldi imitates a bagpipe by having the violas, cellos, and basses sustain long notes outlining the interval of a fifth. The sound is meant to remind the listener of a bagpipe’s drone. The rhythms of the melody are appropriate for dancing, while the lively mood sets the scene for a celebration of spring. The soloist—other than momentarily imitating a bagpipe herself—does not contribute anything in particular to the storytelling. She seems content to interject lively, virtuosic passagework at the appropriate points.

“Spring,” Movement III

Composer: Antonio Vivaldi

Performance: David Nolan with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (2014)

We can also use “Spring” as an opportunity to explore musical timbre, which refers to the particular sound qualities of different instruments and singers. Although it’s difficult to talk about in the same way as we do pitch and rhythm, it is a crucial aspect of music that conveys a lot of information. We will consider three adaptations of “Spring” that showcase differences in timbre.

The first example is performed by the Norwegian fiddler Ragnhild Hemsing and the baroque orchestra Barokkanerne from their 2024 album Vivaldi – The Norwegian Seasons. Hemsing is not playing a standard violin, but is instead playing a hardingfele or Hardanger fiddle. The hardingfele is a folk fiddle from the mountains of Norway that is notable for having four sympathetic strings that run beneath the fingerboard. These strings vibrate along with the bowed strings, producing a thick and resonant sound quite unlike a standard violin. Upon first hearing, it can sometimes sound as if two fiddles are playing instead of one. The hardingfele is also often tuned in an open tuning, which allows the fiddler to play the melody on one or two strings while letting the other strings provide a drone harmony. While violins typically maintain a standard tuning, hardingfele players will use different tunings depending on the tune they are playing. The instrument’s repertoire consists of a number of different folk dances, and fiddlers were commonly employed for weddings, parties, and other special occasions.

The hardingfele has a long history in Norway, and has a rich amount of folklore associated with it. Aspiring fiddlers were said to learn the instrument by consulting with a fossegrim, a type of troll that lives under waterfalls. It is worth noting, though, that the waterfall association likely stems from the fact that fiddlers would practice near waterfalls so they could not be heard. According to the fiddler Knut Hamre, they did this not out of embarrassment, but to avoid getting in trouble for shirking their farm chores. The “trollish-ness” of the hardingfele extends even to the names of its various tuning schemes, with some named “troll-tuning” or “huldra-tuning” (a huldra is a forest spirit similar to a siren or mermaid). Like “regular” European fiddles, hardingfele lore also involves the Devil; the tune “Fanitullen” was allegedly taught to a fiddler by the Devil and playing it supposedly could drive men to commit violence and even murder. These associations with trolls, spirits, the Devil, and dancing led to the hardingfele’s suppression by Norwegian religious authorities in the 19th century, but it has since become a point of pride for the country.

In performing Vivaldi on hardingfele, Hemsing plays some parts differently than usual, which might offend Vivaldi purists, but the results are vivacious and even a little rowdy. In the video below, you can also note the use of period instruments of the Baroque period, including a harpsichord and most notably the large theorbo, a lute with bass strings that extend beyond the instrument’s headstock. The harpsichord and theorbo play the basso continuo, a continuous accompaniment that is common in Baroque music. Rather than play from a fully written part, the continuo players’ music has only the bass notes and uses numbers to indicate the chord types.

Concertor No. 1 in E. Major, Spring I. Allegro

Composer: Antonio Vivaldi

Performance: Ragnhild Hemsing and the baroque orchestra Barokkanerne (2024)

Vivaldi’s violin concertos are also favorites for rock and heavy metal guitarists, as the virtuoso solo sections provide ample opportunity to display their skills. Electric guitars using distortion and amplification are also able to hold single notes for much longer than an acoustic guitar, so they can emulate the violin very effectively. As such, there are a number of metal guitarist YouTubers who have posted arrangements of the Four Seasons concertos. Our example is by the Polish guitarist Marcin Jakubek.

In place of the string orchestra, Jakubek uses additional electric guitar and electric bass parts, along with some synthesized chords in the background to fill out the sound. He adds in a drum kit, which plays loud and fast in a metal style and also adds a lot of rhythmic variety, occasionally employing double bass drums. The main focus is obviously Jakubek’s solo guitar, though, and as a part of his arrangement he includes a number of specialized techniques like sweep-picking (1:18), tremolo-picking (1:30), and tapping (1:35). Like Hemsing’s hardingfele version, Jakubek alters Vivaldi’s original music to better suit his instrument.

Apart from a short break with acoustic guitars, you might note that there is very little variation in timbre in this performance. This is somewhat normal for heavy metal music, as the style tends to focus solely on electric guitar, electric bass, and drum kit, with everything always cranked up “to 11.” It creates a singular and recognizable sound which can be quite exciting and overwhelming, but it also tends to remain consistent for the duration of songs and even entire albums.

Our final example is light years away from Vivaldi’s original concerto in terms of timbre and instrumentation. This is an arrangement for an analog synthesizer by the YouTuber and vintage electronics enthusiast Sam Battle. In it, he takes full advantage of his synthesizer’s ability to shape and create sounds with no equivalent in acoustic instruments. While the ritornello and solo sections use sounds that kind of emulate orchestral winds and strings, Battle also includes a variety of squelchy space sounds and swells that weave in and out of the texture.

One thing that you might notice about this video is that it seems almost as if the machine is playing itself, which is only partly true. The synthesizer is being controlled by a sequencer, which sends it the pre-programmed notes of the piece as digital information. Once everything is set up and programmed, it is then mostly a matter of pushing “play” and watching it go. However, the analog synthesizer itself is controlled by electrical voltage, which determines the pitch but also controls many of the timbral parameters. This technology has been around for a while, originating in the 1960s and popularized by the inventor Robert Moog and his company Moog Music. The synthesizer is also modular, meaning that it is made up of a number of different components that each perform a specific task. These could involve generating the initial sounds or shaping them in various ways. The choice of particular modules, the knob settings, and the routes of the wiring connections can create a wide variety of different results. If it isn’t all set up precisely, there is a good chance that it won’t work at all. There is a steep learning curve and often a lot of expense involved in making music this way, but electronic music enthusiasts enjoy how hands-on and highly customizable modular synthesizers can be, once you figure them out.

Finally, it is worth noting that this video also emulates what is perhaps the best-selling classical music record of all time, Wendy Carlos’s Switched-On Bach from 1968. Prior to this, most electronic music had been more experimental and avant-garde in nature. Carlos’s arrangements demonstrated the potential musicality of the new electronic instruments. Following Switched-On Bach, Carlos composed electronic scores for the films A Clockwork Orange (1971), The Shining (1980), and Tron (1982), and the synthesizer went on to become a mainstay of popular music styles from rock and soul music to techno, new age, and many others. Unfortunately, Carlos’s original music is rather hard to come by in the 21st century because she never made it available for digital streaming or downloading, but CDs are available from the usual places and from her website.

Anoushka Shankar, Raga Madhuvanti

We will conclude this chapter with a consideration of how cultural context can facilitate musical storytelling even in the absence of a specific text. Every example that we have considered thus far has been accompanied at some level by a description. In the case of Berlioz, we had a long prose explanation from the composer himself. In the case of Mussorgsky, references to the titles of paintings. In the case of Vivaldi, a poem. The titles of the two Chinese examples refer us to a historical event on the one hand and a poem on the other, while Likhuta explains how her composition connects with lived experience. This final example also has specific meaning, but it is only available to those initiated into the musical tradition from which it comes. While anyone can enjoy the sounds of “Raga Madhuvanti,” its meaning is unveiled only when one positions it correctly within the web of North Indian musical and artistic practice.

Before we can approach our example, we need to know something about North Indian classical music. It is important to note that this text can provide only a shallow and perfunctory glimpse of a tradition that requires a lifetime of dedication to master. Like their Western counterparts, North Indian classical musicians immerse themselves in their tradition for decades before claiming any sort of authority. But as with European classical music, a listener does not need to master the theoretical nuances in order to enjoy a performance.

Raga Theory

The North Indian classical music of today combines relatively modern instruments and practices with a theoretical system that dates to the 9th century. Here, we will focus on the concept of raga, which is roughly analogous to the scale. Unlike the scale, however, which provides a composer or performer only with a set of pitches and some information about their hierarchy (the first note of the scale, for example, is the most important), a raga carries a great weight of information, both musical and extramusical (having to do with non-sounding elements). Ragas are sometimes used as the basis for fixed compositions, but more often they are explored in an improvised performance—a practice that we will explore below. It is impossible to determine the precise number of ragas in existence. About five hundred seem to be in use at any given time, while an individual musician might master a few dozen.

We will use Raga Madhuvanti as an example. Raga Madhuvanti contains seven distinct pitches, just like the Western scale. However, the pitches found in Raga Madhuvanti are not found in any Western mode. If we were to imagine starting from a major scale, the third pitch would be flat but the fourth would be sharp, creating a large gap between them. In addition, the pitches contained in a raga vary depending on whether one is ascending or descending. The most important scale degree in Raga Madhuvanti is 1, while the second most important is 5.

This video begins by demonstrating the ascending and descending forms of Raga Madhuvanti. It then demonstrates some of the typical melodic fragments before concluding with a sample song.

This is already more information about performance practice than one can derive from a Western scale, but we have only begun. Each of the pitches indicated above must be precisely tuned, for North Indian music employs microtones, or pitches that fall between the keys on the piano. These must be learned by ear—and are unique to a given raga. Each pitch must also be approached and ornamented in the correct manner, for this is a rich vocabulary of slides, vibratos, and trills. Raga Madhuvanti also contains prescribed resting places for the melody as it develops. Any melody played in Raga Madhuvanti will be further shaped by a vocabulary of typical phrases that identify the raga. Finally, one cannot incorporate any additional pitches without destroying the raga.

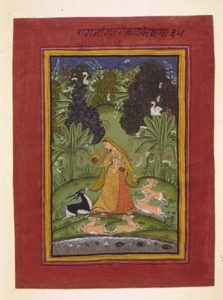

But we have still only begun. It is now time to move on to the extramusical characteristics of Raga Madhuvanti. To begin with, Raga Madhuvanti is used to express gentle, loving, and romantic sentiments. In particular, it communicates the emotion that one feels for one’s beloved. It is also considered sweet and playful. The root of the name, “madhu,” translates to “honey.” The character of the raga is captured in poetry and paintings known as ragamalas. The practice of personifying musical ragas through verse began in the 14th century, which in turn inspired the miniature paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries. There are no classical representations of Raga Madhuvanti, which was developed in the 1930s, but we can still link it to art. Ragas are organized into families, known as thaat, and Madhuvanti belongs to the Todi thaat. Ragas in a family share a variety of musical and extramusical characteristics. Raga Todi is portrayed as a beautiful woman, the wife of Raga Hindol, who is separated from her lover. She is always surrounded by deer, and focuses her attention on the buck, who represents masculine virility.

At this point we’ve wandered a bit far from our topic—but all of this is relevant to the understanding of Raga Madhuvanti, which is traditionally considered to possess a spiritual existence independent of any performance or description. When we say that Raga Madhuvanti was “developed” in the 1930s, that is not quite correct. It might be better to say that it was “discovered,” for most musicians would agree that ragas exist whether or not they are named and performed. When a musician begins to perform a raga, they embark upon the lifelong task of becoming acquainted with it, as if it were another human being. Every encounter reveals new facets of the raga, which cannot be fully captured in any single performance.

Finally, Raga Madhuvanti, like all ragas, is associated with a specific season and time of day. Raga Madhuvanti is an evening raga that should be performed during the fourth quarter of the day—or, roughly, between 4 and 8 pm. It is also considered appropriate for the summer season. At one time, these associations were taken very seriously. The North Indian classical tradition developed in the courts, where musicians played ragas that were suited to the moment. A morning raga for the monsoon season, for example, would be heard only on a monsoon morning. In the courts, musicians played constantly, and were therefore able to maintain correlations between ragas and time markers. With the rise of concert life in the 20th century, however, this became impossible, and North Indian classical musicians today generally perform ragas without concern for time or season. Nevertheless, these associations linger.

Tala Theory

This has been an overview of raga theory, which concerns the melodic and extramusical contents of a performance. Tala theory, which concerns rhythmic content, is equally complex, but we will largely pass over it here due to the fact that it is difficult for untrained listeners to perceive the rhythmic nuances of North Indian classical music. We will note only that a tala is a pattern of beats used in the performance of a raga. The number of beats in a tala can range from three to 128, although most contain between six and sixteen beats. Beats can be strong or weak, and each is characterized by a specific percussive sound. A tala, therefore, is best thought of as a cycle of timbres. This is simple enough, but a drummer will almost never play the cycle unadorned. Instead, they will improvise complex rhythms over the tala, which exists only in the imagination of the performers and listeners.

Ragas and talas are not paired up one-to-one, but only specific talas may be used with a given raga. We will be hearing a performance of Raga Madhuvanti paired with Rupak Tala, which contains seven beats divided into three groups containing three, two, and two beats respectively. North Indian classical musicians learn talas by reciting the syllables associated with each beat, which in turn represent that sound of the drum and indicate how it is to be struck to create that sound. The syllables for the seven beats of Rupak Tala are Tin Tin Na Dhin Na Dhin Na. The most common percussion instrument in North Indian classical music is the tabla, which is a pair of small drums—one a bit larger than the other—that are played with the hands. “Tin” indicates a resonant stroke with the right hand, while “Na” is a damped stroke with the right hand and “Dhin” is a resonant stroke with both hands. An accomplished player will be careful to use the correct fingers with the appropriate force in exactly the right spot on the drum head.

This video includes a demonstration of Rupak Tala. The tabla player performs the basic 7-beat tala. He then begins to introduce variations. However, you can track beats of the tala by tapping or clapping.

Instruments and Transmission

We are finally ready to consider a modern performance of Raga Madhuvanti. We will begin with the instruments, one of which—the tabla—has already been introduced. All North Indian classical music is performed over a drone, which usually consists of the two most important notes in the raga. In the case of Raga Madhuvanti, as noted above, those are the first and fifth scale degrees. The drone is most often performed on a tanpura. This long-necked lute is almost completely hollow and therefore extremely resonant. It has no frets and cannot be used to play melodies. Instead, the performer lightly plucks each of the four strings in turn to create a sustained drone. The tanpura is most often played by an apprentice of the soloist.

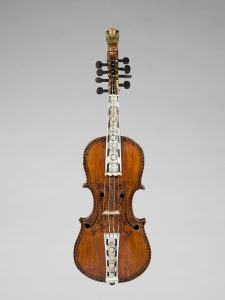

The sitar is capable of producing its own drone, but it is a much more complicated instrument and is used primarily to perform the raga. Today, the sitar is the most common North Indian melodic instrument. It was made famous in the second half of the 20th century by the virtuoso Ravi Shankar, who influenced The Beatles (see Chapter 8) and frequently performed at popular music festivals (including Woodstock, discussed in Chapter 7). The sitar, however, is not a particularly ancient instrument, dating only to the 18th century.

Like the tanpura, the sitar has a hollow neck and is highly resonant. Both instruments also produce a light, metallic buzzing sound that is essential to the timbre. Unlike the tanpura, the sitar has large, arched frets. Melodies are played on the strings that run across them. These strings can either be pressed down, shortening the length of the string, or pulled to the side, increasing the tension on the string. Both actions change the note produced when the string is plucked, and they can be combined to produce the effect of sliding between pitches.

Sitars in fact have three different types of strings. The top three are used to play the melody. Below these are three or four strings that are used to produce the drone. Most interesting, however, are the twelve to fourteen sympathetic strings that run down the neck behind the frets. These strings are tuned to the pitches of the raga and resonate when the same pitches are played on the melody strings, thereby contributing to the vibrancy of the instrument’s sound. They can also be strummed.

Mastering the sitar is comparable in difficulty to mastering the nuances of the raga and tala systems. Traditionally, aspiring musicians committed themselves to a guru, or teacher, at a young age. The student would move in with the guru and become part of the family, completing household tasks in return for musical guidance. Although this system has largely been replaced by private lessons and music schools in the European model, both of the musicians we will discuss here learned their craft immersively in the traditional way. One is Ravi Shankar, who was apprenticed to sarod player Allauddin Khan, and the other is Anoushka Shankar, who learned from her father.

The Shankars

Ravi Shankar (1920-2012) is remembered as the performer who popularized North Indian music in the West. He began his regular tours of Europe and the United States in 1956. At concerts, he focused on educating audiences about his instrument—the sitar—and the North Indian classical tradition, winning fans in the process. In the 1960s he began to form relationships with popular musicians, including George Harrison of The Beatles. He was invited to participate in both of the major popular music festivals of the 1960s: the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival and the 1969 Aquarian Exposition, better known as Woodstock (see Chapter 7). His influence can be heard on a number of rock albums from the era, including The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (see Chapter 8).

Ravi’s daughter Anoushka was born in London in 1981, when Ravi was sixty-one years old. She began training with him at the age of seven, and was soon appearing beside him onstage playing the tanpura. Anoushka gave her first solo performance at the age of thirteen, making her first studio recording shortly thereafter. Although she is certainly a master of the North Indian classical tradition, Anoushka has been primarily interested in cross-cultural collaborations, and has released a series of albums that explore the connections between different musical traditions. Like her father, she has also maintained connection with the world of popular music. Her most frequent collaborator is singer Norah Jones—who also happens to be her half-sister.

Raga Madhuvanti

We will focus on Anoushka’s rendition of Raga Madhuvanti, made live at a Carnegie Hall concert in 2000. Ravi’s recording will serve for comparison, for although both are performances of Raga Madhuvanti, they are quite different and cannot be considered to represent “the same piece.” In the North Indian tradition, the roles of composer and performer are essentially indistinguishable. A player “composes” in the process of performing a raga, improvising melodic motifs and shapes. At the same time, the identity of the raga is paramount, and two performances of the same raga are therefore expected to communicate similar emotional and expressive content.

Both recordings are considerably shorter than a traditional performance, which might extend to an hour or more. This is typical of the modern era, for audiences desire variety and expect to hear several ragas on a concert. Both recordings, however, exhibit the traditional structure of a raga performance, which is in two large parts.

In the first part of a performance,termed the alap, Anoushka introduces the notes of Raga Madhuvanti. This is done slowly and deliberately over the course of nearly ten minutes. She establishes the notes in order, ornamenting them with characteristics slides and melodic fragments. Because the notes of the raga must be presented from lowest to highest, her playing begins in the low range and gradually extends into the high. Once Anoushka has established all of the notes, she gradually introduces a regular pulse into the music. This pulse quickens, and she begins to play with increased rhythmic activity. As a result, the alap, which begins in a meditative mood, concludes with breathtaking excitement.

Alap of Raga Madhuvanti

Performance: Anoushka Shankar (2001)

Our recording of the alap closes with applause from the audience, but this is not the end of the performance. However, musicians in the North Indian classical tradition don’t think of “performance” in the same way as Western classical musicians. There is seldom a clear beginning to the rendition of a raga, which instead emerges gradually from a process of strumming and tuning (activities that a Western player might describe as “warming up”). A performer will often continue to adjust their tuning throughout the alap. These habits reflect the continuity between “practice” and “performance” that is characteristic of the North Indian classical tradition. Every rendition of a raga—whether executed in privacy or before an audience—brings the performer and listener one step closer to really “knowing” it.

The second part of the performance is called the jhala. Its beginning is marked by the entrance of the tabla, which establishes the tala (rhythmic cycle). In this case, we are hearing the seven-beat Rupak Tala, as described above. The role of the sitar also changes at this point. While Anoushka has been freely improvising thus far, now she plays a fixed melody called a gat. Such melodies are usually traditional, and they can be heard in many different performances of the same raga. For the remainder of the jhala, Anoushka improvises using fragments of the gat according to the rules associated with Raga Madhuvanti. One can recognize the gat from time to time as Anoushka works it into the fabric of her playing. As in the alap, she increases the rhythmic complexity and virtuosity of her improvisations as she builds to the exciting conclusion.

Jhala of Raga Madhuvanti

Performance: Anoushka Shankar (2001)

Comparing Performances

A brief consideration of Ravi’s performance of Raga Madhuvanti reveals the flexibility that characterizes the North Indian classical tradition. His alap is very brief: less than two minutes, in comparison with Anoushka’s ten. He establishes the pitches of the raga much more quickly, and his playing is lively from the start. At the beginning of the jhala, he plays a completely different gat, which then leads into an extremely long improvisation—twenty minutes—that, because it is founded on a different gat, sounds nothing like Anoushka’s. In short, the two recordings of Raga Madhuvanti have very little in common. They are not, in a Western sense, recordings of the same piece of music.

This performance of Raga Madhuvanti by Ravi Shankar offers an excellent opportunity to determine what constitutes the essential character of a raga. As the listener will easily observe, it is quite different from Anoushka’s performance.

They are, however, recordings of the same raga, which brings us back to the question that opened this chapter: How can sound tell a story? An experienced listener will hear these two performances as both communicating aspects of the essential character of Raga Madhuvanti. Neither of these performances tells a specific story, containing a narrative, events, or characters (like we encountered in Berlioz’s Fantastical Symphony). However, each is decidedly dramatic, insofar as it engages with and elucidates the extramusical character of the raga. A listener will know that Raga Madhuvanti is associated with the evening and that it expresses romantic love. They might also be familiar with the poetry or paintings that have captured and contributed to the raga’s character. Each performance, therefore, adds to the grander narrative of Raga Madhuvanti—a narrative that stretches across generations and continents.

This example also presents an opportunity to discuss the non-universality of programmatic musical expression. Do you hear these performances as expressing the sentiment of romantic love? Do you hear them as playful? Do you connect them with the evening, or the summer? Do you even hear them as communicating the same emotional content as one another? The answer may very well be no. Most music communicates meaning within a cultural context. In this case, that meaning is determined by the listener’s familiarity with North Indian classical music, with the raga system in general, and with Raga Madhuvanti in particular. A lifetime of exposure to this music will lead one to make the correct emotional connections. Those emotions, however, are not inherent in the music and not obvious to every listener. This is true of every musical tradition.

Resources for Further Learning

Cone, Edward T., ed. Fantastic Symphony: An Authoritative Score. W. W. Norton & Company, 1971.

Church, Michael, ed. The Other Classical Music: Fifteen Great Traditions. Boydell Press, 2015.

Robbins Landon, H. C. Vivaldi: Voice of the Baroque. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Ruckert, George E. Music in India: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. Oxford University Press, 2003.

Taruskin, Richard. Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Online

Wendy Carlos’s Website: http://www.wendycarlos.com/