Unit 2: Music for Storytelling

5 Song

Esther M. Morgan-Ellis and Arielle P. Crumley

Song is perhaps the most familiar and universal form of musical storytelling. Unlike opera, it does not require a large space, costumes, or staging. It can be collaborative, but is often performed by a single person. It is also compelling, for we generally get a great deal of pleasure out of using our imaginations to visualize the characters and events of a story. In many times and places, in fact, song and storytelling have been considered inseparable: The storyteller could not imagine communicating through any means other than music.

The purpose of song, of course, is not always to tell stories. Many songs present philosophical ideas, or describe scenes, or support worship, or encourage dancing. In this chapter, however, we will focus on songs—and collections of songs—that outline clear narratives, and we will examine ways in which the music helps to communicate the story. As we will see, it can do this in many ways.

Song Cycles

We will begin by looking at collections of songs that work together to tell a story that is emotionally complex, if not heavy in plot detail. Such a collection can be called a song cycle. A song cycle usually consists of about eight to twenty songs that use carefully crafted texts and music to present a cohesive narrative. Each song is distinct from the others and the order cannot be changed. While the term song cycle is most often applied to works from the art music world, it is valid across many genres. When a popular artist releases an album of songs that accomplish the purpose of a song cycle, however, the product is referred to as a concept album.

The most important difference between a song cycle and concept album is that the former is most commonly conceived of with live performance in mind, whereas the latter is often developed in the studio and consumed as a recording. For this reason, a song cycle is more likely to have limited instrumentation, while producers of concept albums often have a wider variety of sound tools at their disposal. We will begin by considering a concept album that includes not only sounds but images and spoken poetry.

Beyoncé, Lemonade

On April 23, 2016, popular music star Beyoncé released her sixth album, Lemonade. The release was accompanied by a 65-minute film of the same name that premiered on the popular television network HBO. This album, which was influenced by a range of genres spanning from hip-hop to country, became critically acclaimed for its musical variety, while the accompanying film was admired for its astounding visual cinematography. The work as a whole has also been lauded for its unapologetic celebration of womanhood and black culture.

At its center, Lemonade is a concept album revolving around infidelity, seemingly sparked by the infamous accounts of Beyoncé and husband Jay-Z’s marital struggles. The songs, which mirror Beyoncé’s personal experiences with infidelity, touch on themes such as heartbreak, revenge, and forgiveness. The accompanying film follows the singer’s journey from betrayal to healing by dividing the twelve songs into separate chapters: “Intuition,” “Denial,” “Anger,” “Apathy,” “Emptiness,” “Accountability,” “Reformation,” “Forgiveness,” “Resurrection,” “Hope,” and “Redemption.” Though the album’s focus is on Beyoncé’s personal healing, there is also an underlying political theme, for the album recognizes the struggles of black Americans by addressing issues such as black womanhood and police brutality. Here, we will discuss several songs and consider their visual counterparts, exploring different stages of the story’s development.

“Hold Up”

One of the most noteworthy aspects of Lemonade is the poetry that Beyoncé recites between each song. These poems help to tie the story together and clarify dramatic details. Beyoncé’s recitations include excerpts from the poems of Warsan Shire, a Somali-British poet known for writing about not only personal experiences but also the struggles of women, refugees, immigrants, and other marginalized groups of people. Throughout the recitation, listeners are confronted both with abstract images and with descriptions of the emotions that prevail in each chapter. Consider, for example, the poetry that precedes the song “Hold Up,” which Beyoncé recites in eerie, whispering tones.

“Hold Up” from Lemonade

Performance: Beyoncé (2016)

Immediately following this passage, the song “Hold Up” begins. This upbeat single reflects the “Denial” chapter of Beyoncé’s journey. The song at first seems optimistic: its playful, Reggae-inspired beat and major key make the song sound like a laid-back summertime hit. The lyrics of the chorus seem to convey a positive attitude, repeating the phrase, “Hold up, they don’t love you like I love you/Slow down, they don’t love you like I love you.” However, the verses express more negative emotions. By considering the lyrics in their entirety and noticing the duality between the verses and the chorus, the listener gets the impression that Beyoncé is fighting with her emotions, bouncing back and forth between denial and anger.

The visual aspect of the song also reveals a dichotomous nature. Beyoncé herself seems to be a visual representation of lightheartedness, dressed in a long, flowing gown of bright yellow. However, her look is meant to be a representation of Oshun, a West-African goddess of fresh waters, love, and fertility (this characterization is further emphasized in the beginning of the scene where Beyoncé emerges from a building surrounded by cascading water). Although Oshun is viewed as a benevolent deity, folktales often discuss Oshun’s harsh temper when she has been wronged. Beyoncé embodies this character throughout the song, smiling playfully as she bashes windows, fire hydrants, and cars with a baseball bat.

“Sandcastles”

The next few songs on the album, which belong to the chapters “Apathy” and “Emptiness,” exhibit various emotions, but it is with the song “Sandcastles” that Beyoncé arrives at the most difficult and important point in her journey: “Forgiveness.” The music itself presents raw emotions, with its simple, bare piano accompaniment and expressive vocals. Beyoncé’s singing style is very different in this song, her voice at times sounding shaky or raspy, reflecting the hurt that is inevitable when confronting a cheating partner. She sings of her damaged marriage, of the fights and broken hearts, yet she reveals her reluctance to walk away from it all by singing, “Oh, and I know I promised that I couldn’t stay, baby/ Every promise don’t work out that way.” Like the music itself, the visual portion of this song is very personal, including loving scenes of Beyoncé and husband Jay-Z laughing together and embracing.

“Sandcastles” from Lemonade

Performance: Beyoncé

The following short song, “Forward,” features English singer James Blake, who sings a heartbreaking melody. With the infidelity narrative reaching its conclusion in the previous song, this interlude pulls away from the story of Beyonce’s struggles and introduces a new focus on the previously-mentioned underlying theme: the struggles of black Americans. The visual counterpart of the song features several important figures in the fight for equality and justice, including the mothers of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and Michael Brown (Sybrina Fulton, Gwen Carr, and Lezley McSpadden respectively). Each woman is shown holding a photograph of her son who was killed by unnecessary violence and brutality.

The final chapters of Beyoncé’s journey, “Hope” and “Redemption,” feature upbeat and inspirational songs such as “Freedom” and the hit single “Formation.” The powerful lyrics and gospel style of “Freedom” convey an inspirational message about continuing on in the midst of adversity. This message is not only a reflection of Beyoncé’s power to move beyond her personal struggles while dealing with her husband’s infidelity, it is also an anthem intended to uplift black Americans in their struggles against inequality. At the song’s conclusion, there is an excerpt from a speech given by Hattie White, Jay-Z’s grandmother, that elucidates the meaning of the album’s title:

I had my ups and downs, but I always find the inner strength to pull myself up. I was served lemons, but I made lemonade.

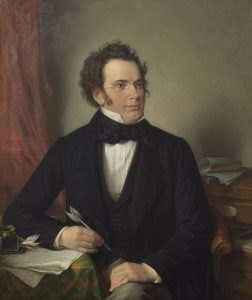

Franz Schubert, The Lovely Maid of the Mill

Franz Schubert (1797-1828) lived a quiet life in Vienna, where he wrote over 600 songs for performance at intimate domestic gatherings. Although he died young, and without achieving significant fame outside of Vienna, his work became widely-known in the mid-19th century and today he is considered to be one of the finest composers of the era.

Song and National Character

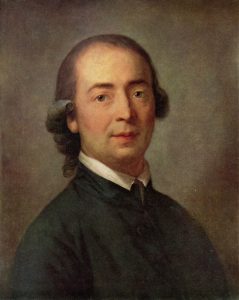

Before we can look at Schubert’s songs, we need to know something about the cultural context in which he was working. In the early 19th century, new ideas about national identity were in the air. Many of these ideas were rooted in the work of German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder, who argued that spoken language influenced an individual’s character. He suggested, for example, that Germans all thought in roughly the same way because they spoke the same language, which in turn guided and structured their intellectual activity. From here, the notion that people who spoke the same language should participate in bounded, self-governing communities—nations, in fact—was not far removed. During Schubert’s time, neither Germany nor Austria existed in anything resembling their present forms, but the idea that communities of people who spoke a common language should constitute autonomous nations was quickly taking hold.

Herder also believed that the most authentic form of national character was to be found among those least corrupted by cosmopolitan influences—the peasants who worked the land. Before the late 18th century, impoverished rural folk were treated with contempt. It was not believed that they had anything to offer the ruling classes other than labor. Following Herder, however, they became the one true source of authentic “folk” culture, and therefore key to a nation’s ability to understand itself.

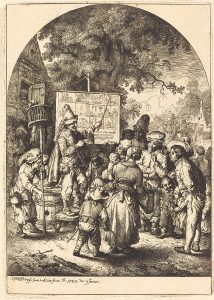

Collectors began to scour the countryside for folk stories, folk poetry, folk dances, and folk songs. These were compiled and published for popular consumption. Perhaps the most famous of such collectors were the Brothers Grimm (Jacob Ludwig Karl and Wilhelm Carl), who were responsible for first recording many of the fairy tales—including Cinderella, Hansel and Gretel, Snow White, Rapunzel, and Sleeping Beauty—that have been ceaselessly told and retold around the world ever since.

All of this is important to our discussion of Schubert for two reasons. First, the elevation of the German language meant that German songs had the potential to become art. Before Schubert’s time, songs were regarded as trivial popular entertainment. Schubert’s songs, however, were taken seriously as cultural expression of the highest order. Second, general fascination with folk culture and art influenced Schubert’s approach to writing songs. He often chose texts that imitated folk poetry, or at least dwelt on rural subject matter, and he frequently set these to music in a folk-like style. Although some of his music seems very simple, Schubert did not resort to the folk idiom because he lacked ability or imagination. Instead, he imitated genuine folk song to augment his storytelling. We will see all of this influence at work in Schubert’s 1824 song cycle The Lovely Maid of the Mill. Before turning to the story and music, however, we need to consider the setting in which the music was meant to be experienced.

Salon Culture

In the Vienna of Schubert’s time, music lovers supported an economy of small, in-home concerts known as salons. A salon might be hosted by a wealthy family for the purpose of advertising their cultural and social capital. The performance would take place in the family’s living room, where visitors could admire their furnishings and art. Hosting a salon was also considerably cheaper than maintaining a private orchestra, so it became the preferred means of cultural expression as Vienna’s wealth slowly shifted from a small group of aristocrats to a larger middle class.

Naturally, certain types of music were preferable for salon entertainment. Only a few performers could fit in the venue at a time, and loud instruments were not welcome. A great demand arose, therefore, for solo piano music, chamber music (two to five individuals each playing their own part), and song, all of which Schubert produced in enormous quantities.

All of Schubert’s songs and chamber music were conceived of with this sort of environment in mind. In fact, he became so prominent in the salon scene that a special term, Schubertiade, was developed to describe a salon performance that featured only his music. Salons were comparatively informal, and listeners would gather around the performers in close proximity. Paintings of salon performances show listeners in rapt attention.

This type of engagement with music was typical more generally of Schubert’s era, when the public held art in high regard and believed that artists were in a position to communicate profound truths. Schubert’s listeners sought not only entertainment but also enlightenment, transformation, and catharsis. The Lovely Maid of the Mill offered all.

The Lovely Maid of the Mill

The poetry for this song cycle was written by Wilhelm Müller, a prolific author of song texts. Müller was one of many German poets who looked to folk models for inspiration, and the folk-like characteristics of his verse influenced Schubert’s music. Müller’s collection of twenty-five poems was first published in 1820, and Schubert began setting it to music just a few years later while he was recovering from a severe bout of illness. Schubert’s spirits were low at the time he embarked on this project, for he feared that he would never fully regain his health. Indeed, he never did: Schubert succumbed to his illness five years later, just as he was on the brink of achieving success outside of Vienna.

In the poems, Müller tells the story of a young journeyman miller who has completed his initial apprenticeship and set out to find employment. He walks through the woods until he finds a stream, and then follows the stream to a mill, where he does indeed find a job waiting. He also finds the miller’s daughter, and falls in love with her immediately. At first, she seems to reciprocate, and he is overjoyed to have won her affection. Slowly, however, the miller begins to suspect that the girl in fact loves the hunter, who has been hanging about the mill. As his suspicion turns to certainty, the miller experiences anger, grief, and finally resignation. Having lost his true love forever, he drowns himself in the brook.

It is worth noting that Schubert and Beyonce’s songs cycles have a great deal in common. Both address the suffering that can come with love, and both express the intense emotions of the wronged party. It seems that we have never told enough stories about the difficulty of navigating a romantic relationship. The nuances of each musical story, however, are unique to the time and place in which each was crafted. Beyonce tells a tale of empowerment and reconciliation, while Schubert’s protagonist seems to give up in the face of a romantic stymy.

The story told in The Lovely Maid of the Mill, however, exhibits a variety of 19th-century values. The period extending roughly from 1815 to 1900 is referred to in the arts as the Romantic era. In the realms of both literature and music, consumers expected insight into the inner emotional lives of individuals, whether they were fictional protagonists or the creators themselves. Two of the topics addressed in The Lovely Maid of the Mill—love and suicide—were especially prevalent in the Romantic era, while the tale’s rural setting exemplifies the Romantic interest in nature. While the story is not particularly interesting in its own terms, the music allows us to experience every nuance the protagonist’s widely varying emotional states.

We will examine four songs: the first, the last, and two from intermediate points in the miller’s emotional journey. In each case, we will look at how Schubert’s musical decisions amplify and communicate the emotional and dramatic contents of the poetry.

“Wandering”

The first song is entitled “Wandering.” The poem reads as follows:

Wandering is the miller’s joy,

Wandering!

A man isn’t much of a miller,

If he doesn’t think of wandering,

Wandering!

We learned it from the stream,

The stream!

It doesn’t rest by day or night,

And only thinks of wandering,

The stream!

We also see it in the mill wheels,

The mill wheels!

They’d rather not stand still at all

and don’t tire of turning all day,

the mill wheels!

Even the millstones, as heavy as they are,

The millstones!

They take part in the merry dance

And would go faster if they could,

The millstones!

Oh wandering, wandering, my passion,

Oh wandering!

Master and Mistress Miller,

Give me your leave to go in peace,

And wander!

translated by Celia Sgroi

“Wandering” from The Lovely Maid of the Mill

Composer: Franz Schubert

Performance: Ian Bostridge and Mitsuko Uchida (2005)

The textual contents, frequent word repetition, and generous use of exclamation points all paint a picture of an enthusiastic (if naive) young man. His outlook is positive and he sees nothing but joy in his future. He also indicates a clear preference for individual liberty. He is not, in other words, the type of young man who is eager to take on the responsibilities of marriage.

Schubert translates all of this enthusiasm and simplistic good nature into his music. He seems to imagine the miller’s words as constituting a folk-type song, which the young man literally sings as he walks through the woods. To do so, Schubert keeps his setting (the music crafted to suit a set of words) very simple. To begin with, he creates a strophic song, in which each stanza of the text is set to the same music. As a result, we hear the same melody and accompaniment five times in a row. This is a standard form for European and American folk music, which is traditionally learned by ear and memorized. One can easily master the melody, which can then be used to sing a limitless amount of text. This form is also common in the Christian hymn tradition. In all of these cases, the focus is meant to be on the meaning of the words.

Schubert’s strophic melody is simple and catchy. The opening melodic phrase is heard twice, as is the last, while the middle section presents an additional melody in sequence (that is to say, it is repeated at a different pitch level—lower, in this case). In total, therefore, this song contains three short melodic ideas, all of which are repeated either verbatim or with a minor alteration.

Schubert’s melody, however, does not quite imitate a folk song. It is in fact fairly challenging to sing, as it contains a number of difficult leaps in the first and third sections. His piano accompaniment also walks the line between simple and sophisticated. It utilizes a straightforward pattern of arpeggiated harmonies (a technique by which the notes in a triad are played from lowest to highest and/or vice versa), none of which challenge the ear, but it is denser and more varied than one would expect in the folk tradition.

Over the course of the song cycle, however, the listener comes to realize that the piano does more than just support the singer. Schubert encourages us to hear the piano as a second storyteller. Perhaps its arpeggiated accompaniments, which are present in almost every song, represents the gurgling of the brook. When the arpeggiations are absent, it is always for a significant reason. The brook itself turns out to be a very important character. In addition to being present in many of the texts, it actually becomes the narrator for the final poem. We don’t know any of this when we first hear the opening song, but in retrospect we must think twice about what the piano has to contribute.

“Mine”

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | Piano introduction | The arpeggios in the left hand of the accompaniment suggest the steady murmering of the brook. |

| 0’10” | A: “Brook, stop your murmering!”… | A melodic motif is repeated at progressively higher pritch levels.. |

| 0’28” | “Through the grove”… | Repetition of another motif culminates in the singer’s repetition of the word “mine” on a loud, high note. |

| 0’49” | Transition | The music shifts to a new key (B flat major). |

| 0’53” | B: “Spring, are these all your flowers?” | This section, which rests briefly on a minor-mode harmony, seems more disturbed than the A section. |

| 1’19” | Transition | The music returns to the original key (D major). |

| 1’24” | A | The A text and music return. |

| 2’01” | Coda | The singer repeats the word “mine;” the pianist provides a concluding passage. |

The eleventh song in the cycle is entitled “Mine!” This song marks the moment when the miller wins the heart of the girl (or so he thinks). The poem expresses his exuberance:

Brook, stop your murmuring!

Wheels, stop your thundering!

All you merry woodland birds,

Large and small,

Stop your singing!

Through the grove,

In and out,

Only one phrase resounds:

The beloved miller’s daughter is mine!

Mine!

Spring, are these all your flowers?

Sun, can’t you shine any brighter?

Alas, then I must stand all alone,

With the blissful word mine,

Misunderstood in this vast universe.

translated by Celia Sgroi

Schubert brings this text to life with equally joyful music. He sets a brisk tempo, and the singer rushes through the words with a sense of youthful excitement. This is most certainly not a folk song. To begin with, it is not strophic, but through-composed—a term used to indicate a song that pairs a unique melody with each line of poetic text instead of repeating the same melody.

This song is also too complex to be perceived as a folk product. Schubert uses a ternary form (A B A), in which the first ten lines of poetry and their accompanying music constitute the A section and are therefore heard at the beginning and end of the song. The A section begins with another sequence. This time, a melodic fragment is heard at higher and higher pitch levels—an indication of the speaker’s excitement. The A section ends with a rapid passage of notes that rocket to the highest pitch on the word “Mine!” The B section, apart from having a unique character, is in a different key than the A section (B-flat major instead of D major). This gives the song an added sense of wonder and delight. The piano accompaniment provides gurgling arpeggiated harmonies throughout.

“Withered Flowers”

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | A: “All the flowers”… | The piano accompaniment is sparse and restrained. |

| 1’08” | A’: “Ah, but tears don’t bring”… | A melodic motif is repeated at progressively higher pritch levels.. |

| 2’09” | B: “And when she strolls” | The mode changes from minor to major and the piano accompaniment becomes more active. |

| 2’44” | B | The text and music of the B section are repeated. |

| 3’18” | B: “Then all your flowers” | The closing passage of the B section is repeated yet again. |

| 3’34” | Coda | The piano accompaniment transitions back to minor as it moves into the lowest range of the instrument. |

Next we will visit the eighteenth song, entitled “Withered Flowers.” At this point, the miller has passed through various stages of suspicion and anger, and he has nearly resigned himself to his tragic fate:

All you flowers

That she gave to me,

They should put you

With me in my grave.

Why do you all look at me

So sorrowfully,

As if you knew,

What was happening to me?

All you flowers,

Why so limp, why so pale?

All you flowers,

What has drenched you so?

Ah, but tears don’t bring

The green of May,

Don’t cause dead love

To bloom again.

And spring will come,

And winter will go,

And flowers will

Grow in the grass again.

And flowers are lying

In my grave,

All the flowers

That she gave to me.

And when she strolls

Past my burial place

And thinks to herself:

He was true to me!

Then all you flowers

Come out, come out!

May has come,

And winter is gone.

translated by Celia Sgroi

The poem begins in a mournful, self-pitying vein, but the final stanzas introduce a glimmer of hope. The miller imagines a future time when his beloved, passing by his grave, will regret her cruelty. He will be dead, of course, but he will also be vindicated.

The form of this poem—a series of eight stanzas—suggests a strophic setting, but Schubert provides something quite different. He sets the first three stanzas to a slow, minor-mode melody that expresses their tragic sentiment. Then he repeats that melody for the next three stanzas. For the final two stanzas, however, he shifts to the relative major (that is to say, he moves from E minor to E major) and introduces a new melody, all of which is repeated for emphasis. At the climactic phrase “May has come,” the singer soars to the highest notes in his range, and the vocal music concludes on a definitively triumphant note.

Once again, however, we would be remiss to ignore the piano accompaniment, which is particularly striking in this example. After seventeen songs in which the piano has sparkled and bubbled, now it has suddenly gone dead. We hear only dry, sparse chords for most of the song. This accompaniment reinforces the sorrowful mood of the miller, who has given up hope. The piano comes back to life with the final two stanzas, and builds in strength as the miller gains confidence. However, the piano also foreshadows the conclusion to this story, which will not be a happy one. Although the singer ends on a triumphant, major-mode cadence, the closing passage into the piano returns to E minor as it fades away and moves into the lower ranges of the instrument. The careful listener knows that the miller’s hope is false.

“The Brook’s Lullaby”

The final song in the cycle is entitled “The Brook’s Lullaby.” The narrator is no longer the miller, who has drowned himself, but rather the brook, which promises to protect the disappointed lover and see that no more harm comes to him:

Rest well, rest well!

Close your eyes.

Wanderer, you weary one, you are at home.

Fidelity is here,

You’ll lie with me

Until the sea drains the brook dry.

I’ll make you a cool bed

On a soft cushion

In your blue crystalline chamber.

Come closer, come here,

Whatever can soothe,

Lull and rock my boy to sleep.

If a hunting horn sounds

From the green forest,

I’ll rumble and thunder all around you.

Don’t look in here

You blue flowers!

You trouble my sleeper’s dreams.

Go away, depart

From the mill bridge,

Wicked girl, so your shadow won’t wake him!

Throw in to me

Your fine scarf,

So I can cover his eyes.

Good night, good night,

Until everything wakes.

Sleep away your joy, sleep away your pain.

The full moon rises,

The mist departs,

And the sky above, how vast it is!

translated by Celia Sgroi

“The Brook’s Lullaby” from The Lovely Maid of the Mill

Composer: Franz Shubert

Performance: Ian Bostridge and Mitsuko Uchida (2005)

For this final song, Schubert again provides a strophic setting, full of repeating melodic fragments. This time, however, he is imitating not a folk song but a lullaby. The melody is gentle and calming. It consists mostly of stepwise motion, and it is free of dramatic leaps and exciting runs. It almost sounds like a real lullaby, but not quite. Once again, Schubert makes things a bit too complicated by moving from E major to A major for the middle section, and by introducing a flatted pitch near the end that suggest E minor. The result is a particularly passionate lullaby with a hint of sadness.

Ballads

The term ballad has been around for a long time, but it has meant different things in different times and places. The term comes from the French word meaning “to dance,” for medieval French ballads were in fact dance songs. Today, we think of a ballad as being a slow, romantic song. That meaning of the term, however, dates only from the late 19th century. For most of history, a ballad has been some variety of lengthy song that tells a story. Ballad traditions of this sort are found across Europe and in North Africa, the United States, and Australia.

Here, we will examine three disparate musical examples that all, nonetheless, qualify as ballads in this sense. Our first example will be the most traditional, insofar as it has been passed down by means of oral tradition for many generations and exists in various versions on either side of the Atlantic. Our second example will be an adaptation of the folk ballad tradition by a 19th century European composer, and our third will be a recent ballad composed by an American singer. All three of these ballads tell stories, but each uses music in a different way.

“Pretty Polly”

We will begin with a ballad from the tradition of the British Isles. Discussing ballads such as “Pretty Polly,” however, presents unique challenges. While each song from Beyonce’s Lemonade or Schubert’s The Lovely Maid of the Mill is a specific musical object that can be identified and described, such is not the case with traditional ballads. This is because they belong to an oral tradition in which songs are passed down from generation to generation by word of mouth without reliance on written sources.

Oral tradition often works like an enormous game of telephone. Each time a new person learns the song, they make small changes to the text and/or music. These changes might be intentional or accidental. Some singers consciously decide to “improve” a melody or alter a few words of text, while others simply forget what they had originally been taught. At first, a song will still be recognizable, but over centuries and great distances it can acquire a text and melody that bear little relation to the original. In some cases, only a line of poetry or the name of a character betrays the link between two ballads that otherwise seem to have no connection.

This is the case with “Pretty Polly.” We will be examining two versions of the ballad as it was recorded by American folk artists in the 20th century. Even these contemporary versions are significantly different, although a listener can easily recognize that each is a recording of the same song. These variations, however, only scratch the surface.

British Antecedents

“Pretty Polly” is a modern descendent of a much older British ballad entitled “The Gosport Tragedy.” Like many ballads, “The Gosport Tragedy” narrated real-life happenings (although with a supernatural twist). Names and details included in some versions of the ballad tie it to documented events that took place in 1726. Ballads were often used to commemorate tragedies, celebrate victories, eviscerate politicians, or spread the news of notorious crimes.”The Gosport Tragedy” falls into this last category, for it tells the story of a ship’s carpenter who murdered his pregnant girlfriend before himself perishing at sea. In the final stanzas of early versions, the spectre of the betrayed girl appears on board the ship to exact her revenge.

As such, “The Gosport Tragedy”—as well as its New World derivative, “Pretty Polly”—can be specifically categorized as a murder ballad. Just as television viewers today like watching shows about crime, so also regular folks of previous centuries enjoyed hearing about the salacious misdeeds of condemned criminals. As a result, the activities of notorious murderers provided fodder for countless ballads. Most murder ballads specifically tell of young women who lost their lives to deceitful lovers.

The purpose of these ballads was not only to thrill and horrify. They also served to instruct and warn. Mothers often sang ballads to their daughters, who received the message that they must withhold sexual favors from suitors until after marriage. The girls in the songs, after all, put their own lives at risk when they agreed to leave their homes for a young man who had not made a formal commitment. In this way, ballads provided entertainment while also enforcing social norms.

“The Gosport Tragedy” first appeared in print around 1760, but this should not be considered the “original” or “correct” version. One of the challenges facing those who wish to study the histories of traditional ballads is that there is never a preserved, authoritative work. While a particular ballad might have begun life as the creation of a specific individual, we almost never know the identity of that person. And, as described above, ballads begin to change immediately upon entering the oral tradition. Most scholars are more interested in examining the many versions of a ballad that proliferate throughout the repertoire than they are in identifying the most authentic version.

The story first told as “The Gosport Tragedy” has appeared under a variety of titles, including “The Cruel Ship’s Carpenter,” “Love and Murder,” “Polly’s Love,” “Molly the Betray’d” and “The Fog-bound Vessel.” Some versions have been published in print, while others have been collected by “ballad hunters,” who visit rural areas to record and preserve products of the oral tradition.

The version known as “Pretty Polly” emerged in the Appalachian region of the United States. Many immigrants from the British Isles—especially the impoverished Scotch-Irish, who came from a region on the border between England and Scotland—paid for their voyage to the New World by serving as indentured laborers in Pennsylvania. After repaying their debt, they headed into the mountainous regions where land could be obtained for little or no cost. These immigrants had few physical possessions, but they brought in their memories a rich tradition of song.

We will examine two versions of “Pretty Polly” as sung by the traditional Appalachian musicians Dock Boggs (1898-1971) and Jean Ritchie (1922-2015). Both grew up in the region, and both learned the song as children from older musicians in their families or communities. Although the two versions were recorded in the same year and share many elements in common, they also contain significant differences. These differences reveal the influence of oral tradition and provide insight into the values and practices of folk music culture.

Dock Boggs

Dock Boggs was born in the small town of Norton, Virginia, the youngest of ten children. Boggs grew up in a musical household: His father sang and several of his older siblings played the banjo. However, none of the children received a formal music education. Instead, they taught each other or sought guidance from other musicians in the community. Boggs began playing on his oldest brother’s banjo, and he learned “Pretty Polly” from his family. He developed a unique playing style based on his observation of African American banjo players at dances, and he sought out the guidance of other black musicians who worked in the area. As a child, however, he never imagined that he might pursue a career in music.

This changed in the 1920s, when parallel technological developments—radio and field recording—fed a booming market for rural Southern music. Radio revealed the enormous demand for rural music, especially among those who had moved to northern cities in pursuit of industrial jobs. Many stations began broadcasting regular “barn dance” programs, which eventually provided work to musicians. At the same time, record companies began sending field representatives into rural Southern communities in pursuit of marketable sounds. Before the 1920s, commercial recordings could only be made in studios, most of which were located in New York City. Beginning in 1923, however, Southern musicians were recorded on site using portable equipment.

“Pretty Polly”

Performance: Dock Boggs (1963)

Boggs had gone to work in the coal mines at the age of twelve, although he continued to play for dances—a source of conflict with his wife, who saw music as a sinful pursuit. During the 1920s, however, he began to see the possibility of a different life. Instead of waiting for a local opportunity, he travelled north to make his first recordings. In 1927 he recorded eight songs for Brunswick in New York City, and in 1929 he recorded a further four songs for Lonesome Ace in Chicago. Just as Boggs glimpsed a professional music career on the horizon, however, the stock market crash of 1929 inaugurated the Great Depression. Doors closed and he returned to the mines.

Although Boggs did not abandon music altogether, hard times lead him to pawn his banjo in the late 1930s, and he did not perform at all for the next quarter century. He had left the coal mines in 1954, ending a 44 year career during which he had miraculously escaped serious injury. Boggs settled down to a quiet retirement. In 1963, however, his fortunes shifted yet again. Beginning in the previous decade, an enthusiasm for Appalachian folk music had swept northern college campuses as part of what is known as the folk revival. One of the leading figures in the revival, Mike Seeger, had heard and appreciated Boggs’s early recordings, and he set out to find him. Within weeks of their first meeting, Seeger had booked appearances for Boggs at all of the major folk festivals and begun to record his repertoire of songs. By the time he passed away, Boggs was firmly ensconced as a major figure in American folk music history.

“Pretty Polly” was among the songs that Boggs recorded in 1927, but for the purpose of sound quality we will examine his 1963 recording for Folkways records. Even these two performances by the same musician are quite different. Boggs does not sing the same set of verses in 1963 that he had sung in his youth, and his timing and inflection have also changed. This is probably not intentional. Folk musicians do not seek to replicate a single ideal performance, and they are prone to forget, discard, alter, and create verses.

Jean Ritchie

Although she was a generation younger, Jean Ritchie’s childhood was very similar to that of Boggs. She was the youngest of fourteen children born to a farming couple in Perry County, Kentucky. Her family carried on a rich tradition of ballad singing, and two of her older sisters were in fact recorded by the most famous Appalachian ballad hunter, Cecil Sharp, in 1917. Ritchie’s family believed strongly in education, and she graduated from the University of Kentucky with a degree in social work in 1946. She took a job in her field, but also pursued music seriously, making her first of many recordings in 1952. Ritchie benefited from the folk revival, which provided a large and interested audience for her music.

“Pretty Polly”

Performance: Jean Ritchie (1963)

Ritchie was an accomplished ballad singer, but she is best remembered for her role in popularizing the instrument heard on this recording, the Appalachian dulcimer. The Appalachian dulcimer is a type of fretted zither, examples of which can be found in many traditions around the world. It is descended from a German instrument and was first built by immigrant craftspeople in Pennsylvania. The Appalachian dulcimer became popular in parts of the region because it is easy to build and play. The body is a simple box. Although the melody is only played on the highest string (or pair of strings), all of the strings are strummed at the same time. The dulcimer can be used to play simple tunes on its own or to accompany singing, although Ritchie in fact preferred to sing her ballads unaccompanied, as she had learned them.

Ritchie’s father played the Appalachian dulcimer, but because he valued the instrument so highly he forbade his children to touch it. Ritchie, however, could not resist, and she taught herself to play in secret. After she had demonstrated a gift for the instrument, her father conceded to teach her. This story is typical of instrumentalists in the Appalachian folk tradition. Children were almost never encouraged to begin playing an instrument or provided with formal instruction. Instead, those who were interested would figure out how to play independently by listening, watching, and experimenting.

Comparing Two Renditions of “Pretty Polly”

The first difference between the Boggs and Ritchie recordings is the instrumental accompaniment: banjo for Boggs, dulcimer for Ritchie. Both singers, however, provide their own accompaniment, which is typical of ballad performances (when they are accompanied at all). Boggs uses the banjo to provide rhythms while at the same time picking out the melody as he sings it. The dulcimer also provides rhythm, but Ritchie does not play the melody while she sings. Instead, she plays various countermelodies on the dulcimer that are distinct from but compliment the sung melody. Both performers provide instrumental interludes between some of the verses.

The melodies sung by Boggs and Ritchie, however, are not quite the same. Each follows the same general shape, starting low, moving to a higher range, and returning to the low range, and the beginnings are almost identical. There are differences, however, in pitch, rhythm, and general timing. The two singers start at the same tempo, but Boggs gets considerably faster as he goes.

We might also compare Boggs and Ritchie as singers. Both sing in a plain, straightforward style, almost as if they are speaking. Neither uses vibrato. They also don’t seem to put any particular effort into expressing the meaning of the text or creating an emotional effect. Instead, each simply sings the words, expecting the story to have an impact because of its dramatic contents, not because of the way in which those contents are communicated. All of this is typical of traditional Appalachian ballad singers.

The most obvious distinction between the recordings, perhaps, lies in the text. Boggs and Ritchie each start the song in quite a different way. Boggs begins with a first person recollection of courting Pretty Polly. This is reasonable, since he is a male singer, but also strange, since he reverts to the third person in the fourth verse. This is perhaps evidence that he learned several versions of the ballad over the years and combined verses from different sources. The first three verses in Ritchie’s version are also in the first person, but this is because she is giving voice to the characters in turn. Her last four verses describe the conclusion of the scene in third person and offer a moralizing final thought. (Other singers, such as David Lindley, have been known to change the end of the story, allowing Polly to turn the knife on her assailant and walk away alive.)

Although the two recordings are obviously of the same song, they have only four verses in common—and even those are not identical. Boggs sings four verses that Ritchie does not, while Ritchie’s final three verses were not sung by Boggs. This observation only applies to these specific recordings, of course. Both singers performed different sets of verses on different occasions, depending on either the setting or their ability to remember the words.

| “Pretty Polly” as sung by Dock Boggs (1963) |

“Pretty Polly” as sung by Jean Ritchie (1963) |

|

Oh I used to be a rambler, I stayed around in town, I courted Pretty Polly, such beauty never been found. |

|

|

Pretty Polly, Pretty Polly, oh younder she stands, With rings on her fingers and lilly-white hands |

|

|

Pretty Polly, Pretty Polly come take a walk with me When we get married some pleasure to see |

Polly, Pretty Polly, come go along with me, Before we get married some pleasure to see. |

|

He led her over hills and valleys to deep At last Pretty Polly, she began to weep |

|

|

Oh Willie, oh Willie, I’m afraid of your way All minding to ramble and lead me astray |

Oh Willie, Oh Willie, I’m ‘fraid of your ways. I’m afraid you will lead my poor body astray. |

|

Pretty Polly, Pretty Polly, you guessin’ ’bout right, I dug on your grave two-thirds of last night |

Now Polly, Pretty Polly, you’re guessin’ about right. I dug on your grave the best part of last night. |

|

She went on a piece farther and what did she spy? A new-dug grave and a spade lying by |

Oh she stepped a few steps farther, and what did she spy, But a new dug-in grave, and the spade lyin’ nigh. |

|

She threw her arms around him and began for to weep At last Pretty Polly, sure fell asleep |

|

|

Oh he stabbed her through the heart and her heart’s blood did flow. And into the grave Pretty Polly she did go. |

|

|

Now he threw a little dirt over her and started for home, Leaving no-one behind but the wild birds to mourn. |

|

|

It’s a debt to the devil for Willie must pay For killing Pretty Polly and running away. |

Epic Recitation

Civilizations around the world have long used song as a vehicle for telling lengthy stories, or epics, many of which concern the founding of an empire. Here, we will consider two examples: an epic of ancient Greece, The Iliad, and an epic of the Mali Empire, The Sunjata Story. These two epics have a great deal in common, for each details the episodic struggles and triumphs of a great hero. The traditions themselves also seem to have elements in common. However, we cannot directly compare the recitation practices associated with these two texts for a simple reason: While the practice of sung epic recitation is alive and well in West Africa, it has not been practiced in Greece for two millenia, and we therefore can only guess at the details.

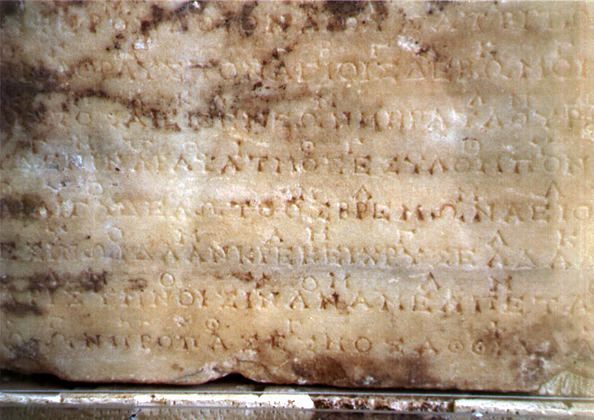

Ancient Greece: The Iliad

In Chapter 4, we explored the origins of European opera and the influence of ancient Greek music on the genre. One of the aspects of ancient Greek music that directly inspired the creation of opera was the notion that ancient Greek poetry and drama were sung in their entirety, not spoken (like what is witnessed when attending a Shakespearean play). Although the lack of surviving musical notation from the period leaves us with little evidence as to how ancient Greek drama actually sounded, the few surviving musical fragments and our theoretical knowledge of both music and poetic recitation in ancient Greece provide us with a good idea as to how Greek poetry and drama might have been sung.

Greek drama grew out of a tradition of community gathering and singing, particularly during festivals and sacrifices in praise of gods such as Dionysus or Apollo. To accompany these celebrations, there would be songs of praise setting dramatic poetry pertaining to the celebrated figures or other mythical beings. Although the tradition began with the community singing these songs in a chorus setting, eventually solo singers would emerge from the chorus to act out the part of the god or hero, while the chorus acted as a narrator or took part in sung dialogue with the soloist. Thus, the beginnings of Greek theatre emerged, and the solo actor and chorus dynamic became a staple in the Greek theatre tradition.

Poetic Meter and Sung Recitation

Many Greek dramas have been preserved through their texts, and many have become well-known classics in today’s world. However, through further study of some of the fragments of poetry from ancient Greece, it is now believed that the poetry and dramas were meant to be performed in musical settings. In later Greek dramas, melodic notation has preserved the ancient sung melodies, but there has yet to be found any surviving form of rhythmic notation from this time. It is understood, however, that the rhythm of the sung words was based off the prosody or meter of the poetry. Poetic meter, similar to musical meter, structures the rhythm of spoken (or in this case, sung) prose. A common example of a poetic meter used in Greek drama is dactylic hexameter. In this type of meter, a poetic phrase is divided into six feet (similar to measures in musical notation). Each foot is divided by what is called a dactyl, a long syllable followed by two short syllables (in this type of meter, a dactyl can also be substituted by a spondee, or two long syllables). When recited, the spoken or sung phrase would follow this pattern of long and short syllables, producing a steady rhythm:

(long-short-short) (long-short-short) (long-short-short) (long-short-short)

(long-short-short) (long-short-short)

One famous example of a Greek epic in dactylic hexameter is Homer’s Iliad. The Iliad was written to be accompanied by a four-stringed lyre, and although there are no surviving fragments of actual melodic notation attached to the poetry, it is believed that this epic was meant to be sung in its entirety. In our example, an interpretation of a passage from the Iliad by classicist Stefan Hagel, the consistent “long-short-short” rhythm of the dactylic hexameter is apparent. The sung melody is an improvisation based on the inflection of the text; for instance, if the approximate pitch goes up at the end of the word in natural speech, it likewise ascends to a higher note when sung. As in this example, the melodies of poetic recitations were probably folk-like in nature: that is to say, simple and repetitive. The tempo is set by the content of the text. In scenes of heightened tension the music may be fast, while the music used in describing a more solemn scene may be slow.

The Iliad

Performance: Stefan Hagel (2017)

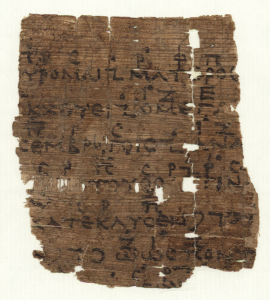

Although most of the musical elements of Homer’s dramas are uncertain and therefore must be left up to the performer’s interpretation, which is based on the nature of the text, there are several surviving fragments of poetry and drama written in stone or on papyrus that are accompanied by written musical notation. The ancient Greeks had a system of musical notation in which a pitch would be associated with a particular symbol, usually a symbol from the Greek alphabet. This pitch’s symbol would be written above the syllable of the sung word. One of the few surviving fragments of music, written on papyrus, comes from Euripides’s Orestes. The play tells the story of Orestes, the son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, who kills his mother to seek revenge for his father’s death. The fragment is of a song sung by the chorus in unison. They sing of Orestes being chased by his mother’s furies, or spirits of revenge.

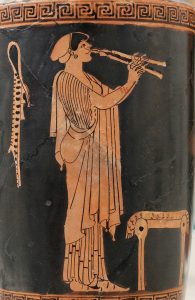

Unlike the simple, repetitive melody that Homer’s words would have most likely been performed to, the melody of the Orestes chorus, believed to be composed by Euripides himself, is through-composed. The melody also differs from the Homeric poetry in that it doesn’t follow the natural inflection of the spoken Greek text, though there are instances in which important words are sounded at a higher pitch for emphasis. The rhythm follows the dochmiac poetic meter, a meter typically used to convey agitation, anxiety, or distress. This sense of distress can certainly be heard in our example. There, we also see the choir accompanied by an aulos, a double pipe instrument. This instrument was often used to accompany choruses in dramatic productions.

As is evident through this performance, with musical translation and a bit of reconstruction this ancient music is now able to be performed with near-perfect historical accuracy. The revival of the music alongside the poetry sheds a new light on the emotional impact of this drama on ancient audiences and allows modern audiences a glimpse of this once-forgotten art that inspired future forms of sung drama.

Ancient Greek epic recitation can be contrasted with this surviving vocal composition, which does not follow the natural inflections of Greek text.

West Africa: The Sunjata Story

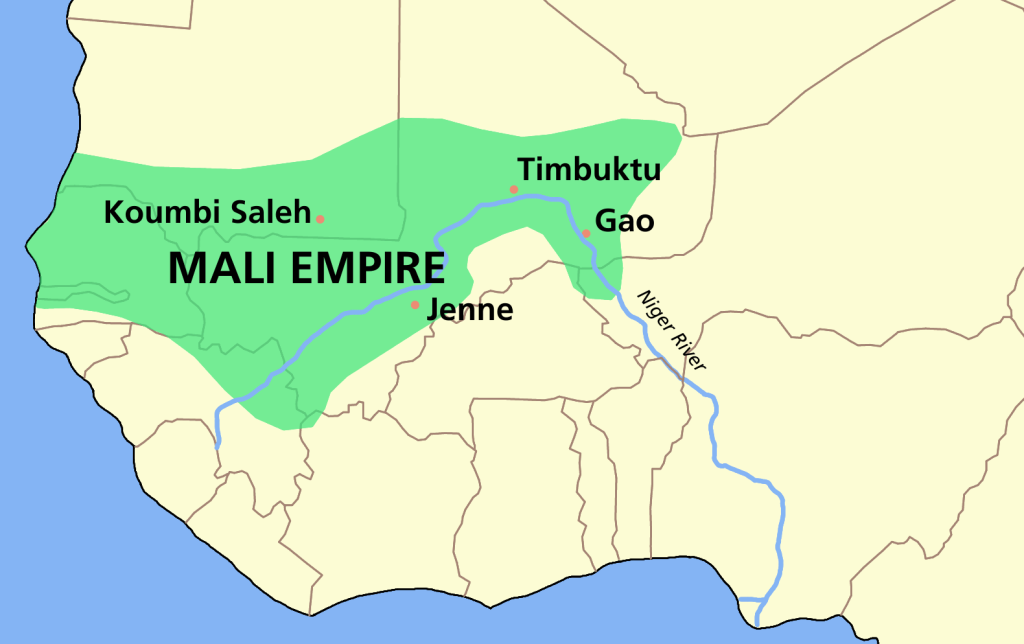

Perhaps the richest extant tradition of epic recitation is to be found among the Mandinka people of West Africa, and their most valued epic is certainly the story of Sunjata, the founder of the ancient Mali Empire. A complete recitation of the Sunjata story can take between six and eight hours. The telling of the story is therefore a remarkable feat in and of itself—all the more so because its words are maintained entirely in the memories of the storytellers. The epic is the property of the jali caste, members of which are responsible for passing it from generation to generation.

Perhaps the richest extant tradition of epic recitation is to be found among the Mandinka people of West Africa, and their most valued epic is certainly the story of Sunjata, the founder of the ancient Mali Empire. A complete recitation of the Sunjata story can take between six and eight hours. The telling of the story is therefore a remarkable feat in and of itself—all the more so because its words are maintained entirely in the memories of the storytellers. The epic is the property of the jali caste, members of which are responsible for passing it from generation to generation.

Founded in 1240, the Mali Empire occupied all or part of half a dozen modern West African countries. It flourished until 1645, when conflict over accession to the throne resulted in the collapse of the empire. Although the Mali Empire was large and powerful, its history has largely been told from outside perspectives. This is because its inhabitants did not cultivate written language, instead maintaining knowledge by means of oral transmission—a process that carries into the present day. The Mandinka, who currently number about 32 million, are the descendents of the Mali Empire, and they continue to celebrate their common heritage through story and song.

Mandinkan Social Structure and the Jali

Before we can examine Mandinkan storytelling practices, we need to know something about the people who tell those stories. Traditionally, Mandinkan society was organized according to a caste system, meaning that social roles were determined by birth and were strictly defined. Members of the jali caste were musicians and storytellers, and their role was to serve the aristocratic caste. (You might be familiar with the French term “griot,” which is more widely used in the West, but members of the community generally prefer the term “jali.”) Although the caste system is officially defunct today, it still exerts an influence on modern society, and jali continue to pass their knowledge and skills down through family lines.

The jali caste was not high ranking, but its members were considered to have special powers and to occupy a unique place in the community. They were considered ritually impure, and were prohibited from wearing the clothes of the aristocracy or sitting on their beds. When they died, they were buried separately from other members of the community. Jali also could not hold political office. At the same time, jali served as advisors to aristocrats and could therefore be very powerful. If a jali was captured in battle, they could not be killed or enslaved, but were expected to serve their captor as they had served their previous master.

The responsibilities of the jali were many. They were musicians, and as such they provided ceremonial music for naming ceremonies, marriages, and agricultural celebrations. They also entertained at dances and wrestling matches and sang the praises of the aristocrats they served. However, the primary role of the jali was to maintain and transmit the knowledge and traditions of the community, including histories, genealogies, proverbs, and laws. If the jali did not fulfill their function, therefore, society itself would disintegrate. Apart from these weighty tasks, the jali also served as moralists, counsellors, spokesmen, public announcers, mediators, messengers, buffoons, porters, tax collectors, and hairdressers.

The jali enjoyed dominion over specific musical instruments. These included the ngoni (a small lute made from wood and covered with goat skin), the balafon (a xylophone in which wood keys are strung over gourd resonators), and the kora. The last of these is certainly the most remarkable, and has retained the deepest connection with the jali tradition. The kora is a type of harp lute, the strings of which are suspended above a large resonator made out of a calabash gourd covered with cow skin. The strings are plucked with the thumb and index finger of each hand. All three of these instruments are used to play complex melodic patterns constructed out of complementary interlocking parts—parts that, at least on the balafon and kora, are each played with one of the two hands.

Traditionally, these instruments were only played by men. Boys would begin to learn from their fathers or uncles, and a jali’s musical education would culminate in the building of his own instrument. A jali also needed to master the tuning systems, which are different for each instrument and quite unlike anything found in Europe. A result of this is that West African music can sound out of tune, although in fact each pitch is carefully positioned. Female jali were musicians too, but they were only trained to sing and play a percussion instrument called the neo. Today, of course, many women excel as performers on all of these instruments.

The Sunjata Story

The Sunjata story is well known, for it has been frequently published in both novel and verse form over the past century and is often included in world literature courses. It constitutes a mythologized retelling of how the historical figure Sunjanta unified the Mali Empire and became its first ruler. According to the epic, Sunjata—whose glorious conquests had been foretold by a soothsayer—was the son of the Mandinkan king’s second wife. As a child, however, Sunjata could not walk, and when the king died it was his half brother who ascended to the throne. Sunjata and his mother were exiled and found a new home in the Mema kingdom, where Sunjata grew strong and gained such widespread support that he was designated heir to the throne. When the Mandinka kingdom was attacked by a malicious power, Sunjata came to the rescue while his half-brother fled in fear. Sunjata’s coalition of small kingdoms defeated the aggressor and resulted in the founding of the Mali Empire.

There are not many recordings of the Sunjata story in existence, for it is carefully guarded. The epic is often related as part of religious ceremonies, and it is believed to bring blessings to all who hear it. Listeners, however, are prohibited from recording these performances. The recordings that are available have been made at formal concerts or recording sessions, and therefore lack many of the elements that would characterize a more authentic performance. These recordings tend to be brief, both because they often omit episodes from the story and because they lack the participatory embellishments that bring the story to life when it is shared in a communal context. Listeners, for example, might join together in singing hymns at appropriate points, or jali might shout out praise songs dedicated to historical figures as they enter the narrative. Participants will also interrupt the story to donate money in return for blessings.

In considering our recordings, therefore, we must be aware that they offer only a glimpse of Sunjata epic recitation as a living practice. Apart from being brief, they are in no way definitive. There are variations in the words that are used to tell the story and even in the events that are related (sometimes, for example, Sunjata and his mother are exiled from the Mali kingdom, while other times they choose to leave for their own safety). The epic is also not always sung to the same melody, nor is the accompaniment stable. The underlying instrumental music might be supplied by kora, balafon, ngoni, or even guitar, and the pattern played by these instruments—known as the kumbengo—can vary in large and small ways.

Comparing Two Renditions of The Sunjata Story

We will begin with a recording made of a 1987 performance in which jali Djelimady Sissoko recites the epic while Sidiki Diabaté accompanies him on the kora. Like all performances, this begins with an instrumental improvisation. At first there is no pulse, but gradually the player settles in to the kumbengo. In this case, we hear the most typical kumbengo for a Sunjata epic recitation, that associated with the Sunjata praise song. The praise song is entirely separate from the epic, but it might be sung during a ritual performance of the epic and the two are closely connected.

The Sunjata Story

Performace: Djelimandy Sissoko, accompanied by Sidiki Diabaté (1987)

The Sunjata praise song is musically related to the recitation of the epic.

The singer enters at the top of his range and then descends down the scale outlined in the accompaniment. This is the typical melodic shape for epic recitation, and it is influenced by the Mandinka language, which is tonal. This means that the inflection of vowel sounds changes the meaning of a word. Because most Mandinka words inflect in a downward direction, setting the words to music naturally produces a descending melody. The vocal ability of a singer is judged in terms of power and confidence. However, the most important quality for a singer to possess is truthfulness. A good singer, therefore, is one whose words are true, regardless of the sound of their voice. The truthfulness of Djelimady Sissoko’s words is confirmed by Sidiki Diabaté, who fulfills the role of witness by chanting naamu, or “indeed,” at the end of every sentence. (If the jali makes a mistake in telling the story, which frequently occurs, the witness must correct it.)

The “groove” is an important characteristic of this performance, as is the rhythmic interaction between the singer and kora player. However, these elements are not simple to perceive or explain. While the repetitiveness of the accompaniment makes it obvious that there is a regular pulse, that pulse is constantly shifting. Try tapping your foot along to the music, and you will soon find that you have lost the beat. This is the result of a concept of rhythm that is based on patterns, not European-style meter. West African musicians, for example, do not count beats in the way European musicians do, and they do not recognize a downbeat (the first and strongest pulse in a metrical grouping). Instead, they transform rhythmic patterns in the way that a kaleidoscope transforms images.

This concept of constant transformation is central to the practice of West African instrumentalists. In this recording, the kora player never repeats the kumbengo pattern unchanged for long. Instead, he makes constant alterations to the rhythmic and pitch content, adding syncopations and ornaments of unending variety. He also interjects virtuosic flourishes in between the phrases of the story. Periodically, the singer pauses to allow for an extended kora solo. While the basic musical contents of the kumbengo are quite simple, therefore, the work of the kora player is complex and sophisticated.

We will briefly examine a second performance of episodes from the Sunjata story for the sake of comparison. This rendition, recorded in 2014, is accompanied by the balafon. Although the balafon, which is a percussion instrument, is quite different from the kora in terms of construction, playing technique, and sound, it executes exactly the same function. Again, the performance opens with an extended solo by the balafon player, Fodé Lassana Diabaté, who eventually settles into a kumbengo that is very similar to that played on the kora. Again, the balafon player constantly alters his accompaniment, adding rhythmic and melodic variations. And again, he occasionally takes the opportunity to improvise extended instrumental solos in between sections of the recited text.

The Sunjata Story

Performance: Hawa Kassé Mady Diabaté, accompanied by Fodé Lassana Diabaté (2014)

The work of the singer, Hawa Kassé Mady Diabaté, can also be compared to the previous recording. Most of her phrases begin high in her range and descend down the scale. She regularly enters during different parts of the kumbengo and does not align her phrases with the accompaniment. And her vocal production is powerful and commanding. She periodically plays a simple percussion instrument, known as a shekere, that consists of a gourd with a beaded cover.

Although this rendition is excellent, its context—amplified on a stage before a silent audience—is far removed from that in which the Sunjata story has thrived for eight hundred years. Jali storytelling is meant to be highly participatory, and this epic only lives when it is endorsed and enriched by the community.

Resources for Further Learning

Church, Michael, ed. The Other Classical Musics: Fifteen Great Traditions. Boydell Press, 2015.

D’Angour, Armand and Tom Phillips. Music, Text, and Culture in Ancient Greece. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Fischer-Dieskau, Dietrich. Schubert’s Songs: A Biographical Study. Limelight Editions, 1984.

Gaines, Zeffie. “A Black Girl’s Song: Misogynoir, Love, and Beyoncé’s Lemonade.” Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education 16, no. 2 (2017): 96-114.

Gustavson, Kent. Blind But Now I See: The Biography of Music Legend Doc Watson. Blooming Twig Books, 2012.

Stone, Ruth M. Music in West Africa: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Taruskin, Richard. Music in the Nineteenth Century: The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Online

KET Education, “Mountain Born: The Jean Ritchie Story”: https://www.ket.org/education/resources/mountain-born-jean-ritchie-story/