Unit 5: Functional Music

12 Music for Moving

Esther M. Morgan-Ellis

Any music that has a regular pulse can cause listeners to tap their feet or clap in unison. Sometimes, however, such coordination of physical activity is the primary purpose of music. This is the case when soldiers sing together while they march, or when a DJ blasts music onto a crowded dance floor. Work songs can coordinate practical labor, such as chopping wood or sowing seeds, while dance music brings people together in an enjoyable social activity. All music related to movement, however, has certain elements in common, for it must relate to the mechanical functions of the human body.

Music for Marching

Music can have a powerful impact on the energy and coordination of marching groups. It not only keeps participants stepping in time but can provide them with motivation as they become tired. For this reason, militaries around the world have accompanied marching with music for untold centuries. No matter when or where such music is created, it is always essentially similar. Music for marching, after all, must be in duple meter (for humans have two legs) and must feature a pulse at a walking pace—brisk for a drill, perhaps, or stately for a ceremony. The pulse must always be clear, strong, and regular, so that marchers can hear and respond to it. Music for marching cannot contain tempo variations, or it would no longer be of use. Music for marching also needs to be loud. Because of its military connections, marching music tends to be firmly associated with a specific nation, for which it can provide patriotic expression. This is true of both examples that we will explore.

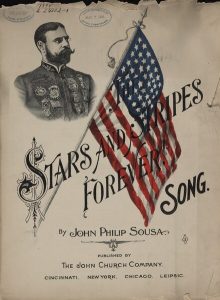

John Philip Sousa, “The Stars and Stripes Forever”

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | Intro | The march starts with a unison melody played by the ensemble. |

| 0’04” | A | A variety of instruments play the melody. |

| 0’19” | A | The A strain is repeated. |

| 0’34” | B | The volume drops as the clarinets and euphoniums take the melody. |

| 0’50” | B | The second pass through the B strain, featuring the trumpets, is considerably louder. |

| 1’05” | C | The volume diminishes again as single-reed instruments take the melody. |

| 1’37” | D | Unison trombones lead off this passage |

| 2’01” | C’ | A piccolo countermelody is added to the C strain. |

| 2’31” | D | The D strain is repeated. |

| 2’55” | C” | A trombone countermelody is added to the C strain; in addition, the trumpets take over the melody, thereby increasing the volume. |

The most prolific and influential composer of marches in the United States was John Philip Sousa (1854-1932). Although he began his career as a military musician, most of Sousa’s marches were intended for concert performance by his band, which toured the world for decades around the turn of the 20th century. For this reason, his marches are particularly interesting to listen to, but they still meet the requirements for functional marching music.

Sousa was born in Washington, D.C., where his father served as a trombone player in the Marine Band. Following some initial private music instruction, Sousa enlisted as a musical apprentice in the United States Marine Corps at the age of 13. He left the military in 1875 to pursue a career in theater music, and over the next five years he performed on the violin and began to develop his ability as a conductor. During this period, Sousa also became an expert arranger—a skill that would serve him well for the remainder of his career. At first he produced orchestrations of popular operas, but later he would make a name for himself as a composer. In 1880, Sousa was asked to produce a series of arrangements of operatic selections for the Marine Band. On the strength of his excellent work, he was invited to rejoin the Corps, this time as director of the Marine Band.

The United States Marine Band

The United States Marine Band has a remarkable history of its own. Established in 1798, it is the oldest of the formal United States military bands, which today number well over one hundred and are attached to all five branches of the military. Of course, the United States military employed musicians long before the Marine Band was formed—and indeed, long before the United States itself came into existence. As early as 1633, the Virginia militia relied on drummers to coordinate drills and maneuvers, and beginning in 1687 the Virginia colonists provided public funds for the purchase of military instruments. The first record of a complete military band dates from 1747, when the Pennsylvania colonists formed regiments.

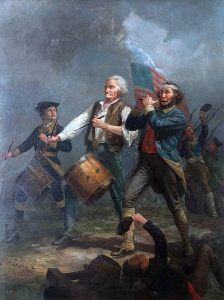

Both drummers and bands supported American troops throughout the Revolution. In fact, musicians have been credited with some of the major victories. At the 1777 Battle of Bennington, for example, the drummers and fifers accompanied troops directly into battle, inspiring the soldiers to soundly defeat the British in what has since been recognized as a turning point in the war. That same year, buglers were added to cavalry units and tasked with coordinating maneuvers by means of bugle calls. At the conclusion of the war, General Washington proclaimed that all military musicians were to be allowed to keep their instruments in recognition of the great hardship they had endured.

The 19th century saw significant improvements both in military music programs and in the construction of the instruments used by military bands. As of 1815, when music was introduced to the West Point curriculum, a military band was likely to include flutes, oboes, bassoons, clarinets, French horns, serpents, bass drums, and tambourines. Soon, however, improved brass instruments—most notably the trumpet, which could now play complex melodies—led to their inclusion in the standard band line-up. These technical developments were the result of new production techniques associated with the Industrial Revolution, and they benefited wind musicians in all settings by greatly expanding the capabilities and ranges of their instruments.

By the time Sousa began his career, therefore, the military band was a large and sophisticated ensemble capable of great flexibility and nuance. Sousa himself aided in the creation of the sousaphone, which is essentially a tuba that has been modified to increase its capacity such that it can be heard over a band. The status of military musicians was also on the rise. General Phillip Sheridan had credited musicians with Union victories in the Civil War, stating that “music has done its share, and more than its share, in winning this war.” The Civil War was certainly fought to diverse musical accompaniment: 28,000 musicians serving in 618 bands accompanied troops into battle, played for ceremonies, and provided entertainment at military encampments.

Sousa’s Career

As director of the Marine Band, Sousa was primarily responsible for providing ceremonial music. Since 1801, the Marine Band has boasted a unique attachment to the White House, earning the nickname “The President’s Own.” The Marine Band plays for all Presidential inaugurations, state funerals, and military funerals at Arlington National Cemetery. It also marks the arrival of visiting heads of state and participates in state dinners and formal receptions. As the premier national music ensemble, it serves as a symbol of military and political might.

Sousa, however, also expanded the public-facing role of the Marine Band. In 1891 he took the band on a concert tour, inaugurating an annual tradition that has carried into the present day. Under Sousa, the Marine Band also released commercial recordings under the auspices of the Columbia Phonograph Company. This was a point of significant contention for Sousa himself. On the one hand, his Columbia recordings made him famous: It was as a direct result of his success as a recording artist that Sousa was able to launch a lucrative private career upon leaving the military in 1892. At the same time, Sousa believed that recording technology marked the inevitable decline of live music as both a professional and amateur pursuit.

For decades to come, Sousa would publicly resist the steady growth of the recording industry while simultaneously profiting from it. 1906 saw the publication of Sousa’s most famous attack on the industry, an article entitled “The Menace of Mechanical Music.” That same year he made the following remarks at a congressional hearing:

These talking machines are going to ruin the artistic development of music in this country. When I was a boy—I was born in this town—in front of every house in the summer evenings you would find young people together singing the songs of the day or the old songs. To-day you hear these infernal machines going night and day. We will not have a vocal cord left. The vocal cord will be eliminated by a process of evolution, as was the tail of man when he came from the ape.

Sousa conjured up an apocalyptic image of parlor pianos fallen silent and children divested of the ability to sing their childish songs. He warns of a future where all music will come from the “talking machine.” At the same time, however, Sousa’s own band was releasing recordings—although Sousa himself almost never conducted the ensemble at recording sessions and was able to proudly state that he was in no way personally associated with the gramophone companies.

Although this might seem hypocritical, the subject of the congressional hearing mentioned above—a new copyright law, intended to protect the rights of composers in the realm of recorded music—casts the controversy in a different light. While Sousa may indeed have genuinely feared the effects of “canned music” on amateur participatory music making, he was primarily concerned with the rights of composers, who were losing income due to that fact that they could not claim royalties on recordings of their works. Until 1909, anyone could make and sell unlimited recordings of a published musical composition or literary work upon purchasing a single copy of the printed product. Composers, lyricists, song writers, and authors were not entitled to royalties, and instead had to watch those in the recording industry get rich from their creative work. In making the above argument, Sousa was trying to appeal to the public and win support for the passage of updated legislation. He was eventually successful: The Copyright Act of 1909 guaranteed compensation to composers and authors whose work was reproduced in a recorded medium.

Sousa also worried that “canned music” would prevent people from attending live performances by the Sousa Band, for such concerts were the main source of income for Sousa and his musicians. The Sousa Band toured constantly, making visits not only to all parts of the United States but to countries around the world. In total, the band gave well over 15,000 concerts between 1892 and 1931. A typical concert would include transcriptions of popular orchestral works, operatic excerpts (complete with vocal soloists), virtuosic instrumental solos, and—most thrilling of all—newly-composed marches by Sousa himself.

The Stars and Stripes Forever

We will consider Sousa’s most famous march, “The Stars and Stripes Forever.” According to Sousa, he composed this march in his head in late 1896, shortly after hearing about the death of his manager and friend David Blakely. It was premiered in early 1897 and met with immediate success. Ninety years later, in 1987, “The Stars and Stripes Forever” was designated as the National March of the United States of America by an act of Congress.

In addition to performing “The Stars and Stripes Forever” at concerts, the Sousa Band made several recordings of the march. Even more profitable, however, were Sousa’s various arrangements for performance by amateur musicians. These included versions for piano (two, four, or six hands), zither (solo or duet), one or two mandolins (solo or with piano accompaniment), guitar (solo or duet), banjo (solo or duet), and banjo with piano. In addition, Sousa published full band arrangements for all of his marches—although he was careful to include many part duplications between the instruments, so that even a small town band with only a few members would be able to give a successful performance.

“The Stars and Stripes Forever” provides a typical example of a Sousa march. Its form might be summarized as: intro A A B B C D C’ D C’’. It begins with a brief but loud introduction by the whole band. This is followed by three distinctive melodic passages, or “strains,” the first two of which (A and B) are repeated. Each of the strains is in the major mode, and each—naturally—features the regular pulse of percussion and low brass. Next, an interlude (D) interrupts the pleasant mood of the strains: Blasting brass belt out chromatic scales and dissonant chords, exploring minor-mode territory while climbing to successively higher pitch levels. It is a relief, therefore, when the third strain returns (C’), now with a piccolo countermelody floating over the topic. Another interlude (D) sets up a final rendition of the C strain. Now elaborated upon even further, C’’ features both the piccolo countermelody and an additional countermelody in the trombones. The resulting cacophony is undeniably exciting.

Dance Music in the United States

Dance music has many of the same demands as march music. It needs to be loud so the dancers can hear it over the sounds of their movements. It needs to have a steady tempo so as to propel the dance forward. It shouldn’t be too melodically complex, since the dancers won’t be playing close attention. And it often needs to be repetitive so that dancing can carry on at length.

Because dancing often takes place indoors, one is more likely to hear an instrument that has been used to accompany dancing throughout Europe for many centuries: the violin. The violin is terrifically convenient as a dance instrument. It is small and, therefore, highly portable. It can play a fast melody, but it is also capable of providing harmonies. It is fairly easy to hear, given its high range and bright timbre. And it can be played standing up—perhaps even by the same person who is calling out the dance instructions. For all of these reasons, violin has emerged as the most popular instrument to accompany dancing from Hungary to Texas.

We will begin our tour of dance music in the United States, therefore, with one of the oldest traditions: The fiddle-driven dance music of the Southern Appalachians.

Appalachian Square Dancing: Tommy Jarrell, Fred Cockerham, and Kyle Creed, “Arkansas Traveler”

To see the violin at work as a dance instrument, we will first visit an influential fiddler who lived in North Carolina, Tommy Jarrell (1901-1985). Jarrell developed a unique fiddling style that was both loud and rhythmically exciting, and which was therefore well suited to Appalachian square dancing. We will also consider a recording made by two other musicians from the same region, Fred Cockerham (1905-1980) and Kyle Creed (1912-1982). Although their style was at first limited to Surry County, NC, it has since been adopted by fiddlers and banjo players around the country.

Before we can consider either Appalachian dancing or the music that accompanied it, we need to understand how the instruments used in this tradition found their way into the Southern Appalachian mountains. In addition to the fiddle, mountaineers soon took up the open-backed banjo—an instrument, unlike the violin, that is indigenous to the American South. The combination of fiddle and banjo proved ideal for dancing: Both instruments can play melody while also maintaining rhythmic drive.

The Fiddle

The fiddle was brought to the New World by immigrants from the British Isles and mainland Europe (particularly Germany). Some were lucky enough to bring physical instruments, but many instead brought the recollection of how a violin looked and sounded. These individuals then built their own instruments using available materials. Such homemade fiddles had their shortcomings, but they attest to the importance of music in the lives of impoverished mountaineers who had few material possessions.

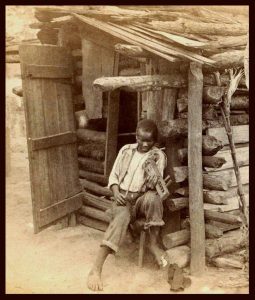

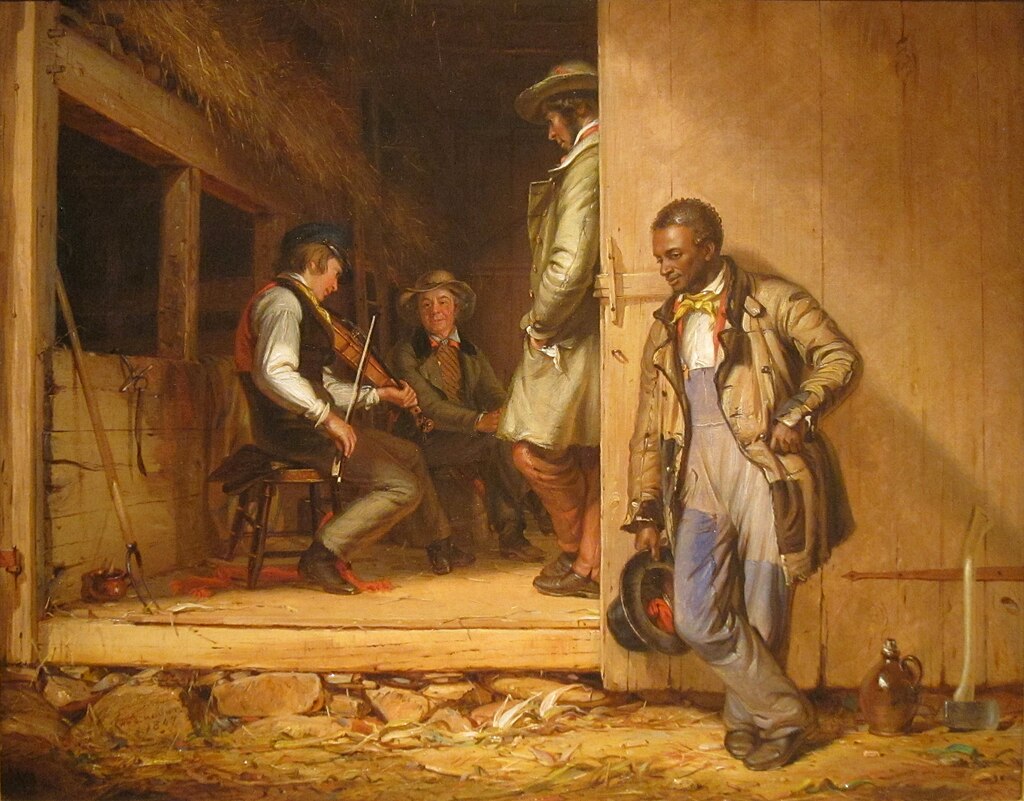

The fiddle was played with equal enthusiasm by black and white Americans. As early as the 1690s, enslaved people were tasked with mastering the instrument so that they could provide music for dances. These performers were expected to supply the latest European dance tunes, but they would introduce rhythmic characteristics that have their roots in West African music. They also played their fiddles for entertainment within the enslaved community—often under the fascinated gaze of white onlookers, who sought to imitate their playing. In this way, a uniquely American style of dance music emerged on Southern plantations. When African Americans left the plantations and moved into the mountains, whether enslaved or free, they brought their music with them.

The Southern Appalachians were populated primarily by poor immigrants from the Ulster province of Ireland. These individuals, known in the United States as the Scotch-Irish, crossed the Atlantic as indentured servants, after which they repaid the cost of their passage by working on plantations in Pennsylvania. Upon fulfilling their labor contracts, Scotch-Irish immigrants travelled into the mountains in search of available land. There, as they labored side-by-side with free and enslaved blacks, music often became an important point of exchange. Tunes and playing styles alike were shared across racial lines, with the result that the Scotch-Irish repertoire was soon transformed, reinterpreted, and expanded.

The Banjo

While the fiddle is a European instrument that underwent change in the hands of Southern African Americans, the banjo is an African American instrument that was transformed by professional white performers in the North. The earliest banjos were built by enslaved people and played for their own amusement. The first recorded mention of a banjo dates from 1781, when Thomas Jefferson noted that the instrument had been “brought hither from Africa.” The banjo is indeed derived from West African lutes, including the akonting and the ngoni. These instruments share important features with the early banjo, including a round neck and strings of unequal length (one is shorter than the others and used to provide a regular drone).

The 19th century saw the transformation and popularization of the banjo in the hands of white musicians. The process began in the 1830s, when the banjo was adopted by minstrel show performers as the representative instrument of plantation life. Over the next few decades, blackface minstrelsy swept the nation, becoming the most popular form of theatrical entertainment in the United States. Minstrel shows were premised on the imitation of African American music, dance, and speech. Although minstrels advertised their authenticity, most knew little of life in the South and instead borrowed their materials from the Anglo-American comedic and musical traditions. In order to portray various stock characters, performers would blacken their faces with burnt cork and dress in the rags of the slave or the finery of the free Northern dandy. They would also accompany their singing and dancing with the instruments of slavery—most notably the banjo.

As a minstrel instrument, the banjo underwent several important changes. It borrowed the flat neck and frets of the guitar, which facilitated the performance of melodies. A fifth string was added, thereby expanding the instrument’s range. And the body of the banjo developed its characteristic round shape: The instruments built by enslaved people were often constructed out of gourds, but 19th-century minstrels began to stretch skin heads across discarded cheese hoops. The instrument was played in a style known as clawhammer or frailing in which the performer uses the nail of their index finger to strike melody strings on strong beats while sounding the short fifth (or drone) string with their thumb in between melody notes.

The popularity of blackface minstrelsy is complicated to explain. The practice certainly traded on racist stereotypes and derogatory humor, but it also reflected a genuine interest in black culture and creativity. Consumers of minstrelsy believed that they were getting an authentic glimpse of plantation life—and they often found the characters sympathetic and appealing. The most vicious characterizations arose after the Civil War, when Northerners began to fear an influx of newly-liberated African Americans. At the same time, black performers sought to gain acceptance (and make a living) by putting on minstrel shows of their own. Incredibly, they had to wear dark makeup and imitate the antics of white minstrels in order to be considered authentic.

The impacts of minstrelsy were felt throughout the American popular music landscape. Indeed, they continue to resonate into the present day. Here, however, we will focus on the popularization of the banjo, which soon became a mainstream instrument. In fact, by the late 19th century, it had become an acceptable alternative to the piano for young ladies, while both male and female banjo orchestras proliferated into the 1920s. The banjo became a staple in early jazz, and could be heard in every dance band. The banjo also spread throughout the rural South, where white players were influenced both by traveling minstrels and by the African American musicians in their midsts.

Dancing and Mountain Life

This brings us back to the Southern Appalachians, where rural mountain dwellers played the fiddle and banjo both for entertainment and for profit. The image of the carefree hillbilly strumming a banjo on his porch is, of course, profoundly misleading: Mountaineers worked hard and lived precariously, and they often did not have the leisure to indulge in music. All the same, if they wanted to be entertained, they had to entertain themselves, and music helped to pass the time at home.

Musicians could also earn money by playing at dances. Square dancing—although frowned upon by certain churchgoers—was a popular form of entertainment. A dance would usually take place inside of a home on a Saturday night, and people would walk great distances to attend. All of the furniture would be moved outside, and the floor might be sprinkled with cornmeal. The musicians—or perhaps just a single fiddler—would stand in a central doorway and play as loudly as possible. To play for a dance, a fiddler only needed to know one tune, which could be repeated all night if necessary. Dances could become quite rowdy, and young women were often prohibited from attending. Those who did show up would pay a little money, some of which would be handed over to the musicians—unless they were simply compensated with dinner.

Appalachian square dancing is descended from social dances of Europe and the British Isles, although it has taken on unique forms. The dancers are organized either into squares of four couples or large circles containing any number of couples. They engage in a variety of familiar and repetitive interactions, usually following the instructions of a dance caller. Dancers might grasp hands to turn around one another, exchange places, dance in couples, gallop up and down lines, or weave amongst one another. The dances can go on indefinitely, although the caller usually brings them to an end after ten or fifteen minutes.

In this video, a caller leads participants through the figures of a square dance to the accompaniment of “Arkansas Traveler.”

Such dances require music with a steady pulse, a fast pace, and an emphasis on the off-beat: Dancers move with a continuous down-and-up motion, and they frequently add individualized footwork between the basic steps. While it does not matter which specific tune is played for a dance, the style of the performance is therefore very important.

The Musicians of Surry County, NC

This brings us, finally, to Tommy Jarrell, Fred Cockerham, and Kyle Creed, all of whom contributed to the development of a unique and highly danceable style in Surry County, NC, in the early 20th century. Of the three, only Cockerham was a professional musician. Indeed, it was very uncommon for mountaineers to pursue music as an occupation. There was more money to be made in manual labor, with the result that only those with physical handicaps (most often blindness) were likely to resort to music as a primary source of income. Like many rural musicians of the era, Cockerham found work with a traveling medicine show, advertising a rhubarb salve made by the South Atlantic Chemical Company. It was grueling work that required constant travel and frequent live radio performances in distant cities.

Creed was an expert carpenter and stone mason, and he made a living in construction. In the 1960s, however, Creed built a banjo for his friend Fred Cockerham. It was a success, and over the next two decades Creed applied his carpentry skills to the production of about two hundred banjos. His work as a luthier, or instrument builder, was enormously influential. Creed’s banjos, which are highly prized, had several unique features, including a shorter neck than had previously been typical. Today, most open-backed banjos are built following his design. Creed was also an expert fiddler and banjo player. Like many Appalachian musicians, he learned to play from older male relatives, including his father, uncle, and grandfather.

Jarrell charted the most typical course through life. As a boy, he learned to play banjo and fiddle from his father, who made a living as a farmer. Jarrell would often provide dance music with his father and his uncle: The three men would stand in different rooms, each playing the fiddle at top volume. Upon his marriage in 1923, however, Jarrell took a job in road construction, operating a motor grader for the North Carolina Highway Department, and played fiddle and banjo only for his own entertainment. Work like his, however, hardly left the laborer with excessive time and energy for leisure pursuits, and Jarrell largely gave up music for much of his adult life. He returned to his instruments only in the 1960s, following the death of his wife. His exuberant style attracted many admirers, and aspiring musicians began to visit him at home, where Jarrell’s legendary hospitality won him many friends.

We are going to consider two performances of the tune “Arkansas Traveler.” This is one of the best-known Appalachian fiddle tunes, and it is characteristic of the repertoire. Like almost all fiddle tunes, “Arkansas Traveler” is in binary form. Each of the two sections in repeated, resulting in an A A B B pattern. Both the A and B sections end with the same concluding gesture, however, which becomes one of the characteristic elements of this tune. It is also typical for the two sections of a fiddle tune to be played in different ranges. In “Arkansas Traveler,” the A section is in the low range, while the B section is high. (Fiddlers traditionally referred to these as the “course” and “fine” sections, in reference to the relative thickness of the low and high strings.) The whole tune can be repeated as many times as desired.

“Arkansas Traveler” is additionally interesting because of its connection to a popular minstrel show sketch. The origins of the tune itself—first published in Cincinnati, OH, in 1847—are unclear. It gained popularity, however, as part of a humorous skit in which a city gentleman stops to ask a mountaineer for directions. The mountaineer routinely misunderstands the traveler and delivers a series of humorous punchlines at his expense. The skit entered circulation as early as the 1820s, and initially portrayed an interracial encounter. Later, when the “Arkansas Traveler” tune and accompanying fiddle-driven story were added (the mountaineer cannot remember how to finish the tune, and is grateful when the traveler takes up the fiddle and plays the final phrase), it was reworked to address anxieties surrounding class relations. Some versions portrayed the mountaineer sympathetically—others, less so.

We will begin with Jarrell’s fiddle version of “Arkansas Traveler.” Jarrell’s influence on the old-time fiddling tradition cannot be overstated, and his style has a number of distinct features. First, he almost never plays on just one string. Instead, he adds harmonies by bowing on two (or even three) strings at the same time, or by dipping his bow to sound the lower strings while he plays a melody in the high range. Second, he prioritizes rhythm over melody. Although you can hear the notes of the tune, Jarrell never sacrifices rhythmic drive. He also emphasizes the off-beats, changing the direction of his bow in between the rhythmic pulses of the tune and thereby introducing syncopation. You can imagine how he could play for a dance all by himself. There is no need for additional instruments to supply harmony or rhythm: Jarrell does it all.

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’01” | A | Jarrell establishes a lively dance rhythm with his bow; this remains consistent throughout the performance. |

| 0’07” | A | Jarrell repeats the A strain. |

| 0’16” | B | The B strain is in a lower range in this version. |

| 0’23” | B | Jarrell repeats the B strain. |

| [0’31” …] | AABB etc. | Jarrell continues to play in this pattern for the remainder of the song. |

The second most common dance configuration would be fiddle and banjo. The practice of combining fiddle and banjo was first documented among enslaved people in 1774, and it developed first in the African American community. The fiddle and banjo produce a heterophonic texture, since each plays an idiomatic version of the same melody (that is, a version suited to the instrument). In this recording we hear Cockerham on the fiddle and Creed on the banjo (although both men played both instruments, and they often switched roles).6 Unlike Jarrell, Cockerham plays only the melody notes, although his bowing patterns also create syncopated rhythmic patterns. Creed closely follows the melody on the banjo, but because his instrument works so differently he does not play exactly the same notes. In between beats, he periodically hits the short fifth string with his thumb, thereby emphasizing the syncopated character of the music. Occasionally, he produces an arpeggio by slowly strumming across the strings from lowest to highest, ending on the melody note.

“Arkansas Traveler”

Performance: Fred Cockerham and Kyle Creed

Swing: Irving Berlin/Fletcher Henderson, “Blue Skies”

In the previous section, we talked about the social dance practices of rural America, where workers gathered in private homes and danced to the sounds of fiddle and banjo. The same desire to engage in social dancing as a form of leisure was also prevalent in cities. Whether one worked on a farm or in an office, dancing offered an opportunity to have fun, drink alcohol, and socialize with the opposite sex. In cities, however, dance practices developed along quite different lines. After all, there was a great deal more money to made, and dance musicians were in constant competition to provide dancers with the most novel and exciting music. This, in combination with technological developments on the one hand and a large, youthful consumer base on the other, led to rapid developments in the urban dance music of the early 20th century.

“Blue Skies”

Composer: Irving Berlin (arr. Fletcher Henderson)

Performance: Benny Goodman and His Orchestra (Remastered 1991)

1920s Social Dancing

We have already visited with a 1920s dance band: That led by Paul Whiteman (Chapter 7), whose “sweet jazz” records swept the market. By the 1930s, however, Whiteman’s style was already out of date. To begin with, new inventions were changing the instrumentation of dance bands. The electronic microphone allowed the plucked string bass to replace the tuba. The string bass had a more percussive articulation and could play at faster tempos, with the result of intensifying dance music. The banjo, which had featured a built-in resonator that allowed it to project, was replaced by the developing electric guitar. Strings and woodwinds, such as the clarinet and oboe, disappeared in favor of saxophones and brass, which came to be organized into large sections. The size of bands increased to about seventeen players, while the drummer took on an more active role in maintaining rhythmic energy.

All of these changes took place in response to the dancers, who were developing increasingly energetic and athletic steps. The most influential new dance of the era was the Lindy Hop, which was introduced by a pair of African American dancers in 1928. Early dancers—mostly young African Americans in Harlem—sought to outdo one another in an attempt to impress white “slummers,” who got a thrill from visiting clubs and ballrooms in black neighborhoods. The Lindy Hop went mainstream in the 1930s and young people across the country imitated wild new steps that they saw in ballrooms, on stage, or in films.

The Lindy Hop has been a competitive dance since its inception. Today, dancers from around the world face off in formal competitions.

The new musical style that developed to accompany the Lindy Hop and other related dances was soon known as swing, a term that now refers both to the dances themselves and to the characteristic uneven, or “swung,” rhythms of the music. These rhythms reflected the relaxed and informal movements of the dancers, who rejected the upright posture and precise steps of older styles. The term, however, was first used by African Americans to describe well-played music and the euphoric emotions it produced. The widespread adoption of the term—along with expressions such as “cool,” “hip,” and “in the groove”—paralleled the growing interest in black culture and music among white musicians and audiences.

Goodman, Henderson, and the Rise of Swing

Despite enthusiasm among urban young people, it took a while for swing music to catch on. In 1935, however, clarinetist and bandleader Benny Goodman (1909-1986) was able to connect with a demographic of young white listeners who propelled swing music into the forefront of the American conscious. The key to Goodman’s success was the radio. In 1934, he secured a spot on the national radio program Let’s Dance. The show featured three bands, each of which played a different style of popular dance music: Latin, sweet, and hot. Goodman’s band represented the “hot” style, but listener response indicated that the other styles were generally preferred. A disastrous national tour in the summer of 1935 confirmed the band’s poor reception. Upon arriving in Hollywood, however, Goodman was greeted by cheering fans. These young West Coast listeners had been listening religiously to Goodman’s band, which always played after midnight on the East Coast and therefore had received little exposure in all but the westernmost time zone.

Goodman’s style was derived from the work of African American arranger Fletcher Henderson (1897-1952). During his years working as a pianist and bandleader in New York City, Henderson produced creative and danceable arrangements of hit popular tunes. Although these arrangements were first intended for his own band to perform and record, Goodman purchased Henderson’s catalog outright in the mid-1930s and introduced the arranger’s hard-driving, rhythmic style to a mainstream audience. Henderson also produced new arrangements to suit Goodman’s needs. In 1939, Henderson joined Goodman’s band, which was one of few integrated bands active in the Swing Era.

Henderson was one of the key architects of the swing style. He abandoned the free-wheeling improvisation of Dixieland jazz in favor of carefully-scripted parts for instruments organized into sections. Although he also produced original compositions, Henderson based most of his arrangements on the melodies of popular songs. We will be considering his treatment of Irving Berlin’s 1926 “Blue Skies.”

Blue Skies

Irving Berlin (1888-1989)—a Russian immigrant to New York City—was one of the leading song writers of the early 20th century. Although “Blue Skies” first gained traction on the musical theater stage, the song really took off with Al Jolson’s 1927 performance in The Jazz Singer—the first commercially successful “talking picture.” Today, “Blue Skies” is regarded as a jazz standard. Its popularity among jazz musicians, however, is due expressly to the success of Henderson’s brilliant arrangement, which he created for Goodman in 1935.

Henderson’s “Blue Skies” opens with an introduction in which the trumpets and clarinets call back and forth to one another over a pounding rhythmic pulse. The chorus of “Blue Skies” is then presented by the band. The melody is in A A B A form, which Henderson reflects in his instrumentation. The first two A sections are played by the trumpets, while the two phrases of the B section are played by the saxophones and trombones respectively. Finally, the saxophones round out the melody with the final A section. Henderson, however, does not merely reproduce Berlin’s tune. He adds melodic flourishes, unusual harmonies, and—most importantly—unpredictable syncopations. By doing so, Henderson reimagines what was already an outdated song for a new generation of dancers.

The remainder of the arrangement consists of repeated passes through Berlin’s tune, each more creative than the last. The melody itself slowly recedes from the foreground, although snippets are always audible. For the second pass, the trumpets (now muted) take the A section again, but this time with constant interruption from the saxophones, resulting in a call and response texture. A solo saxophone player provides the remainder of the melody, but during the final A section he substitutes an improvised alternative melody. What should have been a third turn through the “Blue Skies” tune begins with an improvised trumpet solo, backed up by saxophone interjections. The melody returns with the B section, which is introduced by the trumpets and finished by the saxophones. The concluding A phrase is likewise split between those instruments. A final turn through the melody begins with a clarinet solo by Goodman himself, but ends with the entire band playing the concluding A phrase. The effect is exciting: We hear the full force of Goodman’s horns, backed up by the driving power of the rhythm section.

Disco: Chic, “Good Times”

African American musicians and dancers have had an outsized impact on American popular music since the turn of the 20th century. We have already considered ragtime, Dixieland jazz, and swing—all dance-rooted styles that attracted large audiences and influenced the course of musical development. The trend continued: In the 1950s, black rhythm ‘n’ blues artists laid the groundwork for rock ‘n’ roll. Soul emerged as gospel singers brought the sounds of the black church into the mainstream, while funk developed from the combination of soul-infused vocals with jazz harmonies and the interlocking rhythmic layers common in African-derived traditions. Also in the 1960s, producer Berry Gordy created his signature sound at Motown Records in Detroit and built a roster of black performers who were able to withstand the British Invasion.

Disco Dancing

We will pick up the story in the 1970s, when black artists contributed significantly to another dance tradition: disco. Disco, however, is decidedly multiethnic. It bears traces of funk, but also the rhythms of Latin America, and it was first associated with a community that was bound together not by race but by sexual orientation. Eventually, it would come to be embraced as the musical style of the 1970s counterculture, and discos would become meetings places for people from all walks of life.

The birth of disco dancing and music can be traced to 1970, when New York City DJ David Mancuso began throwing private parties in an underground venue. His clientele consisted primarily of members of the gay community, most of whom were black, and all of whom were regularly harassed by the police when they visited commercial gay bars and clubs. Disco soon captured the interest of other groups, including Latina/o/x and Italian Americans, and venues proliferated in cities like Philadelphia and San Francisco. By 1975, disco has become a national craze, appealing to everyone who sought an escape from the political and economic pressures of the decade.

Disco music is primarily characterised by its fast tempo, “four-on-the-floor” beat (meaning that every pulse in a quadruple meter framework is emphasized), and dense textures. Disco tracks are usually founded on a rhythmic groove consisting of chicken-scratch guitar (a playing technique used to produce a rhythmic, pitchless sound), a variety of percussion instruments, and electric guitar riffs. This is underpinned by a syncopated electric bass line. In addition, however, one might hear piano, electric guitar, electric piano, synthesizers, and orchestral instruments. The resulting music is irresistibly groovy, but also full of variation, since the instruments enter and leave the texture throughout a given track. In short, it is exactly the kind of music that makes people want to dance.

Because disco music was intended for dance clubs, not radio play, it was released in a different format than rock music. Rock singles were usually about three minutes long, and were released on 45 rpm 7-inch discs. Rock albums—which were oriented toward listeners, not dancers—featured a curated selection of songs on a 33 ⅓ rpm 12-inch disc. Dancers, however, required long stretches of music, and the 7-inch single was not convenient for use in clubs. Disco producers, therefore, because designing their songs for 12-inch discs. Instead of offering variety, however, they would stretch out a single track until it took up an entire side—about twenty-two minutes. DJs would then facilitate smooth transitions between discs to keep a crowd dancing through the night.

Chic was one of the most successful disco bands. The group was formed by guitarist Nile Rodgers and bassist Bernard Edwards in 1970, although it was not until 1976 that they took the name Chic. In 1977 they were joined by drummer Tony Thompson, and soon thereafter by singers Luci Martin and Alfa Anderson. The band had a string of hits in 1978 and 1979, but disbanded following the rapid decline in disco’s popularity.

Good Times

We will examine their 1979 song “Good Times.” It is a fine representative of the disco style in its own terms, but it also proved seminal in the development of hip-hop, which we will consider next. The members of Chic publicly stated that every one of their songs contained a “deep hidden meaning,” which could be discerned through careful examination of the lyrics. The lyrics to “Good Times” are, on the surface, a series of straightforward calls to party and enjoy oneself. However, they contain several quotes from Depression-era songs, including the title line of “Happy Days Are Here Again,” which we examined in Chapter 10. According to Rodgers, these references were a commentary on the dismal economic situation of the late 1970s, which paralleled that of the 1930s. In this light, “Good Times” takes on something of a grim character: It invites the listener to engage in escapist party behavior, but also offers a reminder that the challenges of life will still be waiting.

“Good Times”

Composers: Nile Rogers and Bernard Edwards

Performance: Chic (1979)

Of course, there is no reason to assume that the average consumer would give any attention to the words. “Good Times” was a hit because of its danceable beat. After an opening synth swoosh, the track launches into a groove consisting of handclaps, drumset, a repetitive guitar riff, and a funky bass line. A piano occasionally enters the mix, while the sound of strings wafts above. The vocals are delivered in a detached, staccato manner that further contributes to the song’s rhythmic energy. Near the middle of the track, the texture is reduced to handclaps, drums, and bass. One by one, the other layers—Fender Rhodes electric keyboard, piano, guitar, and strings—are reintroduced, with the effect of rebuilding the energy level in this 12-inch dance club version of the single. “Good Times” was one of the last disco songs to top the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.

Hip-Hop: The Sugarhill Gang, “Rapper’s Delight”

Hip-hop was also born in New York City, although it grew out of the needs and creative impulses of another disenfranchised community: black youth in the Bronx. During the 1970s, poor neighborhoods in New York City were devastated by cuts to municipal and federal funding. The city itself faced dire budget shortfalls, with the result that one fifth of all public workers were laid off in 1975 alone. This meant that police and fire forces shrank, classrooms became more crowded, and basic utilities fell into disrepair. Landlords—no longer able to maintain decaying tenements—turned to arson, while rates of homelessness, prostitution, and crime all skyrocketed. By 1979, the New York subway—home to 250 felonies every week—was the most dangerous public transportation system in the world. In what has been termed “white flight,” those with the means to flee the city left for more hospitable communities. This depletion of the tax base plunged the city even further into debt—a debt now shouldered only by the residents without the money or connections needed to begin a new life elsewhere.

The Birth of Hip-Hop

The hardest-hit neighborhood was the Bronx, which by 1977 had become, in the words of the New York Times, “a symbol of America’s woes.” The demographics of the Bronx were radically transformed during this decade. Overall, the population plummeted by 20%. This was largely due to “white flight”: While white residents numbered over a million in 1970, making up 73% of the borough’s population, over half left the Bronx, reducing the white population to only 47% by 1980. At the same time, the black and hispanic populations grew, constituting 32 and 34% of the population respectively by 1980. Many of the new residents immigrated from Caribbean nations and from Puerto Rico, bringing with them the popular music styles of Latin America.

Hip-hop emerged when impoverished youth living in the Bronx sought ways to express and entertain themselves. The music and dance that we will consider here were part of a complex of practices that also included visual art (graffiti) and characteristic modes of dress and speech. All of these served to identity the practitioners, build and enforce community bonds, and provide a creative outlet. Hip-hop culture was also extremely competitive, and those active as musicians and dancers worked constantly to develop new techniques, sounds, and moves that would distinguish a practitioner from the crowd.

The first pioneers of hip-hop music were DJs, who borrowed their tools and techniques directly from the disco. DJs would provide music for block parties and community dances by playing the disco, salsa, and funk records that the dancers loved. In playing records, however, these DJs played careful attention to crowd reactions and developed unique approaches that stimulated dancers to greater activity. DJ Kool Herc (Clive Campbell, b. 1955 in Jamaica), for example, noticed that dancers’ energy increased during the breaks—passages in dance music in which the melody recedes and we hear only the rhythm section. To take advantage of this, he began to play two identical records at the same time, backspinning one to repeat breaks while the other continued to sound over the loudspeakers. Later, Theodore Livingston (b. 1963) noticed that backspinning created a scratching sound that could be used to add rhythmic excitement to the track. In this way, DJs transformed recorded music and laid the groundwork for a completely new style.

At first, DJs confined themselves to operating the turntables. DJ Kool Herc and a few others, however, began reciting rhymes over the breaks, thereby becoming the first rappers. Soon, DJs began recruiting dedicated rappers known as MCs (an abbreviation of “master of ceremonies”). Many of their rhymes were connected with the African-derived tradition of the “toast,” in which a skilled orator tells a story celebrating a protagonist’s cunning and resource. Although the toasting tradition had largely died out in black culture, it survived in prisons and was captured on the hit 1973 album Hustler’s Convention, which had an enormous influence on early MCs.

The dance style that developed alongside hip-hop was highly individual and expressive. “Breaking” derived its name from the rhythmic breaks isolated by DJs, whose music came to be known as “breakbeat.” Dancers, known as “b-boys” and “b-girls,” performed increasingly acrobatic moves in response to the DJ’s looped breaks, which in turn inspired the DJ to generate more intense rhythms. Individuals and crews often entered into direct competition with one another, engaging in dance battles that took place within a circle of onlookers.

The 1973 album Hustler’s Convention captures the toasting tradition and had an enormous influence on early hip-hop.

For most of the 1970s, hip-hop was regarded as a performance practice, not a genre of music. It was an approach to the presentation of dance music that involved looping breaks, scratching records, and reciting rhymes. The early DJs and MCs, however, never considered the possibility of recording their music or seeking commercial success outside of the Bronx. In fact, most refused invitations to enter the recording studio. For this reason, the first hip-hop records were made not by the pioneers of the style but rather by relatively unknown performers working with studio musicians.

Rapper’s Delight

This was the case with the first hip-hop hit, “Rapper’s Delight.” In 1979, New Jersey-based producer Sylvia Robinson recruited three local MCs—Michael “Wonder Mike” Wright, Henry “Big Bank Hank” Jackson, and Guy “Master Gee” O’Brien—to create a hip-hop record for Sugarhill Records. The group called themselves the Sugarhill Gang, and they recorded “Rapper’s Delight” in a single take with a live band hired for the occasion. In keeping with the disco model, the fifteen-minute single was released on a 12-inch disc. It sold over two million copies in the United States, peaking at 36 on the Billboard Hot 100 charts and proving that there was a large commercial market for hip-hop.

“Rapper’s Delight”

Composers: Nile Rogers, Bernard Edwards, and the Sugarhill Gang

Performance: The Sugarhill Gang (1979)

MCs usually rapped over breaks from pre-existing songs. It is therefore not surprising that “Rapper’s Delight” should borrow from a recent hit: Chic’s “Good Times.” In this case, the original record was not used directly. Instead, the studio players performed the handclaps, drumset pattern, bass line, piano riffs, and synth hits from “Good Times” live while the MCs took turns rapping. All the same, the borrowed music is immediately recognizable. Nile Rodgers certainly recognized it when he heard a DJ playing “Rapper’s Delight” in a New York club. At first he was extremely angry and threatened to sue, but the matter was quickly settled and Rogers and Bernard Edwards were credited as co-authors. Later, Rogers came to admire “Rapper’s Delight,” citing its originality and cultural significance.

The lyrics to “Rapper’s Delight” are typical of early hip-hop. The MCs boast about their skills and accomplishments, encourage the listeners to dance, celebrate the party lifestyle, and play with patterns of rhythmic syllables. At one point, the rapping gives way to a break, which could have been looped in live performance to facilitate dancing. Most characteristic of this record, however, is the fact that it is founded on pre-existing music. Hip-hop artists would continue to borrow and reimagine musical material for the purpose of paying homage, providing commentary, and exhibiting their own creativity. The resulting tradition is rich with intertextual references.

Dance Music in Concert Settings

In the last section, we considered four musical examples that were all created expressly to facilitate dancing. That doesn’t mean that this music can’t be enjoyed by a listener—indeed, it often is. However, these have been examples of practical dance music.

In the next section, we will consider dance rhythms and forms adapted to purely musical ends. This essentially takes us back to where the chapter started, with John Philip Sousa’s concert marches. Here, however, we take a look at composers who each used the popular dance styles of their time and place to inform music that was meant primarily for listening.

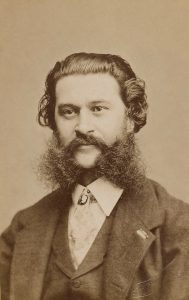

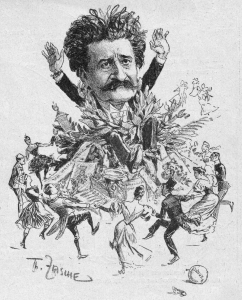

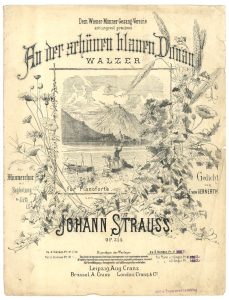

Johann Strauss II, Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka and The Blue Danube

In 19th-century Vienna, Johann Strauss II (1825-1899) was known as “The Waltz King.” His dance-inspired compositions were enormously popular, and by the time of his death he had accumulated countless honors and plaudits. Strauss’s music is also uniquely tied to Viennese identity: It is played by the Vienna Philharmonic every New Year’s Eve and presented on nightly concerts for the benefit of tourists to the city. In total, Strass composed over 400 waltzes, polkas, and quadrilles. Although his orchestra did sometimes play for balls, Strauss’s fame and influence resulted from concert performances, and many of his compositions are not suited to dancing.

Strauss’s Career

Strauss carried on the legacy of his father, Johann Strauss I (1804-1849), who was largely responsible for transforming the waltz from a rustic country dance into a dance for the sophisticated urban ballroom. Johann I, however, forbade his sons from pursuing careers in music. He knew from experience that a musician’s life was strenuous, and he wanted stable, middle-class business careers for his own children. When he caught Johann II practicing the violin one day, therefore, he beat him severely. Johann II, however, was not to be deterred. Throughout his youth he secretly studied violin and composition with members of his father’s orchestra, and in 1844 he assembled his own orchestra and put on a concert at Dommayer’s Casino (a venue in which his father had frequently appeared, but that he subsequently boycotted).

The concert, which included popular selections of the day in addition to four of Strauss’s own compositions, was a great success, but the young orchestra leader still found it difficult to compete with his father. He spent much of the first few years of his career touring outside of Vienna, and was only able to build his local reputation following his father’s death. Soon, however, Strauss had established himself as a musical trend-setter in the city, and in 1863 he was finally appointed Music Director of the Royal Court Balls—a position that had in fact been created for his father, but which Strauss was long denied due to his support for the rebels during the 1848 Vienna Revolution.

We will consider two of Strauss’s most famous compositions: Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka (1858) and The Blue Danube (a waltz composed in 1866). Both of these works were created for concert performance. While it would be possible to dance to them, at least in part, each contains elements that are intended to appeal to the listener and that might even foil any attempt to dance.

Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka

Invention of the polka is traditionally attributed to a housemaid working in Czechspeaking Bohemia. According to legend, she attracted attention with a lively dance set to a regional folk song. Admirers asked her to teach it to them, and the dance quickly spread throughout the countryside. Whatever its origins, the polka was certainly a fixture in Prague ballrooms by 1837, and it was being danced in Vienna by 1839. Next to the waltz, the polka was certainly the most successful European ballroom dance of the 19th century. Within a few decades, it was being danced throughout central and western Europe, up north in the Netherlands and Russia, to the east in India, and in the New World, where it was popular from Mexico to the midwestern United States.

The term “polka” is believed to be derived from the Czech word for “half,” and therefore probably refers to the duple meter of polka music. The dance is performed by couples, who embrace while performing a distinctive step (evocative of tripping or galloping) as they whirl around the room. Dancers tend to bob up and down in time to the beat. The polka is always performed at a fast tempo, and it is one of the more energetic 19th-century ballroom dances.

Strauss composed his Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka for performance in Pavlovsk, Russia, where he had the honor of conducting the summer concert season at the Vauxhall Pavilion every year between 1856 and 1865. These performances often stimulated his creativity, and Strauss created some of his most memorable works for these concerts. In 1858, he was inspired to write a polka that captured the excitement and thrill of gossip—for which “Tritsch-Tratsch” (an equivalent to “chit chat”) was current Viennese slang.

Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka

Composer: Johann Strauss II

Performance: Wiener Philharmoniker (2020)

Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka is certainly full of energy. Its characteristic motif—heard right at the beginning—is a rapidly ascending octave. The melody is played primarily by high-pitched instruments, such as the violin and flute, while the tinkling triangle emphasizes the offbeats. The polka is in a ternary form (A B A), each section of which contains its own repeating melodies. The A section has an internal form of a b c a, while the B section has the form d d e d e d. In short, Strauss deploys an excellent balance of contrast and repetition. The polka starts with an exuberant trill and ends with a hilarious sequence of outbursts from the flutes, oboes, and brass. The regular duple pulse in a fast tempo is maintained throughout, with occasional emphasis from the snare drum or cymbals.

The many musical details of Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka make it worth listening to. If one is dancing, it is more difficult to appreciate Strauss’s clever and delightful orchestration. At the same time, this music is perfectly suitable for dancing—although in such a case the orchestra might choose to repeat the B and A sections one or two times more before playing Strauss’s remarkable ending. In this case, therefore, we have music that was created for the concert stage but that could also live in the ballroom with minimal adjustment.

The Blue Danube

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | Intro | Flutes and horns hint at the first waltz theme; tremolo strings shimmer in the background. |

| 1’27” | Waltz 1 | Internal form: abb. |

| 2’34” | Waltz 2 | Internal form: aaba. |

| 3’34” | Waltz 3 | Internal form aabb. |

| 4’33” | Waltz 4 | Internal form: intro aabb. |

| 5’43” | Waltz 5 | Internal form: intro aab. |

| 6’56” | Coda | Unlike the preceding waltzes, the coda—which revisits many of their themes—contains no direct repetition and includes many transitional passages. |

| 8’16” | The theme from Waltz 1 returns; after a passage of calm, it builds to an exuberant climax. |

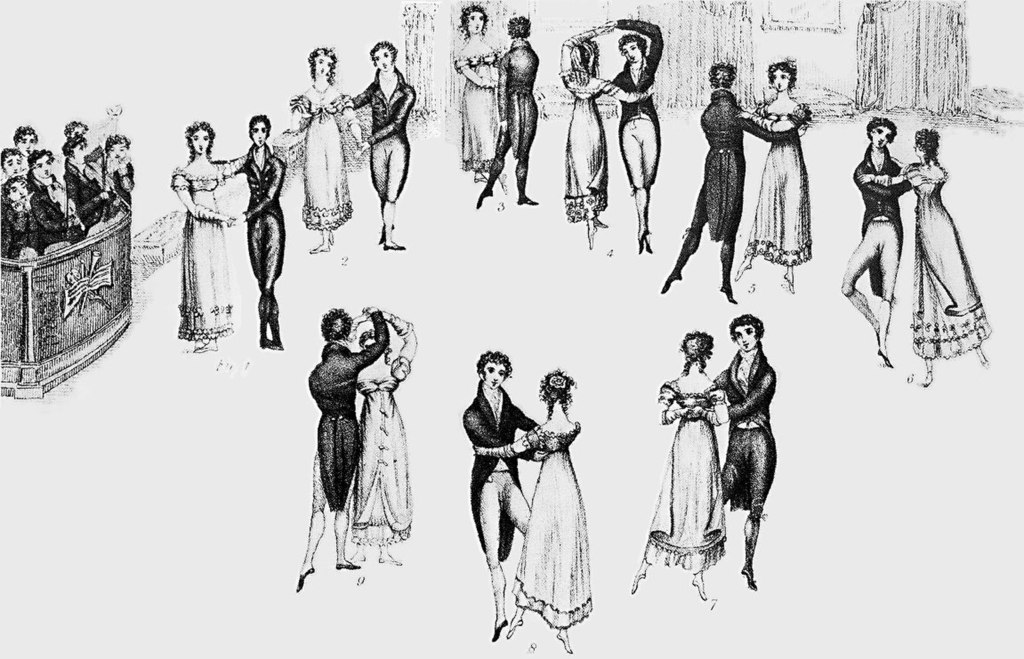

The Blue Danube has additional features that tie it to concert performance. Before considering those, however, we need to consider the waltz as a ballroom dance. Like the polka, the waltz seems to have originated in the Bavarian countryside, although it is somewhat older, perhaps dating to the mid-18th century. When the waltz first entered urban ballrooms, it proved something of a shock: Never before had pairs of dancers held each other in such a close embrace. In older ballroom dances, such as the minuet, the dancers kept a respectful distance from one another, but when waltzing a man actually put his hand around his partner’s waist. Soon, however, dancers had become accustomed to this new style, and by the 1780s the waltz was common in Vienna and beginning to spread around Europe. It was Strauss himself, however, who—building on the legacy of his father—ensured the dance’s popularity throughout the 19th century.

The waltz calls for smooth, gliding motions, and is therefore quite unlike the polka. A mid-19th century waltz was energetic but stately—the tempos, therefore, were moderate. The waltz is in a characteristic triple meter, with dancers moving down and forward on the first beat, but rising up on the second and third. This is reflected in the music, for the first beat (or downbeat) is usually stronger and sounded in a lower range than the others (often intoned as “boom-chuck-chuck”). In Vienna, it became typical for the orchestras play the second beat just a little early, thereby producing a sense of weightlessness in the last part of the pattern.

The Blue Danube actually began life as a choral piece. It was commissioned by the Vienna Men’s Choral Association, with whom Strauss had already enjoyed a two-decades-long association. While Strauss was supposed to be at work on his choral waltz, Austria suffered a bitter defeat in the Seven Weeks’ War with Prussia. The conflict sapped morale in Vienna, with the result that the choirmaster encouraged Strauss to write an exceptionally joyful and lighthearted piece in order to lift the audience members’ moods. A satirical text was added by the Choral Association poet, although it was apparently disliked by both the singers and the audience. As a result, the reception accorded The Blue Danube at its premiere on February 15, 1867, was surprisingly tepid for a waltz that would become Strauss’s most popular composition. A more serious text—that sometimes sung today—was appended in 1889. However, The Blue Danube is most often heard in its purely orchestral form, and it was as an instrumental piece that it became famous following a performance at the World Exhibition in Paris later in 1867.

Unlike Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka, The Blue Danube is a fairly lengthy piece with a complex form. Like Strauss’s other waltz-inspired concert pieces, it consists of a string of independent, self-contained waltzes—five, to be precise—preceded by an introduction and followed by a lengthy coda. The introduction hints at the theme of the first waltz, while the coda revisits themes from the first four waltzes, concluding with a grandiose statement of the same theme with which the piece timidly opened.

One could not dance to this version of The Blue Danube: The introduction starts too slowly and is too tentative, while the coda would confuse dancers with its unorthodox form and frequent transitions. The individual waltzes, however, could easily be extracted for ballroom use. Each is in binary form, the A and B sections of which each contain the correct sixteen measures and expected repeats. Although each of the waltzes contains two distinct themes, the standard waltz rhythm (“boom-chuck-chuck”) is never absent.

Resources for Further Learning

Bierley, Paul E. The Incredible Band of John Philip Sousa. University of Illinois Press, 2010.

Dils, Ann and Ansley Cooper Albright. Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader. Wesleyan University Press, 2001.

Jamison, Phil. Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Southern Appalachian Dance. University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Lott, Eric. Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. 20th anniversary edition. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Malone, Jacqui. Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance. University of Illinois Press, 1996.

Taruskin, Richard. Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Turino, Thomas. Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. University of Chicago Press, 2008.