Unit 2: Music for Storytelling

3 Music and Characterization

Esther M. Morgan-Ellis

Music may have originally developed for the purpose of communication, and it has become a powerful tool in the telling of stories. Over the next four chapters, we will explore ways in which music has been used to convey, enhance, or transform stories in a variety of cultural contexts.

Most storytellers use music with great care. They do so because it is powerful. Music can help to set the mood in a video game, or allow a character on stage to express emotion by singing, or add interest and gravity to the recitation of an epic poem. It can encourage an audience member to get more involved in a performance, either emotionally or by joining in with the music-making. It can help a listener to remember the words to a story. And it can “say” things that go beyond words and images.

Music is used to tell stories in many different ways. Sometimes it accompanies images, such as in a film. Sometimes it is combined with stage action, as in ballets and musicals. Sometimes it is paired with a text, which might be sung or provided to the listener to read. Of course, we can choose to hear a story in any piece of music, and we will encounter examples later in this book that seem as if they must be communicating something, even if we can’t say exactly what it is. In the next four chapters, however, we will examine pieces of music that are used to tell clearly defined stories, and we will focus on understanding how music enriches and impacts those stories.

John Williams, Star Wars

We will start with an example that is familiar to most listeners: the music created for the Star Wars films. We will examine this music on its own terms, but through it we will also encounter five other works and styles that strongly impacted the creation of this score. No art exists in a vacuum. New works are built upon old, and creators rely upon cultural memory to communicate meaning. Even the Star Wars films were not conjured out of a vacuum—director George Lucas based his creation on Akira Kurosawa’s 1958 samurai film The Hidden Fortress.

You probably already have a wealth of associations with the Star Wars soundtrack—both personal and general—as a result of having watched these films. On the personal level, you might find that this music evokes nostalgic memories of watching Star Wars with your family as a child, or it might make you uncomfortable if you found the films particularly scary or sad. Such responses are valid and worth exploring. Here, however, we will focus on objective characteristics of the music that help us to explain how it enhances the story.

Williams’s Career

The soundtrack to the Star Wars films was composed by one of the most prolific and influential of all cinema composers, John Williams (b. 1932). Williams’s career took off in 1974, when director Steven Spielberg recruited him to score his first feature production, The Sugarland Express. The two went on to produce a string of hit films with memorable soundtracks, including Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T., Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, the Indiana Jones films, and the first two Jurassic Park films. This kind of collaboration has long played a role in the production of great music, and we will see similar partnerships at work in opera and ballet. It was Spielberg who recommended Williams to George Lucas, the director of the Star Wars films. His scores for the original Star Wars trilogy—A New Hope (1977), The Empire Strikes Back (1980), and Return of the Jedi (1983)—are among the best-known musical works created for the big screen.

Williams—who had studied music at UCLA and the Juilliard School— certainly knew his music history and concert repertoire. He also had decades of experience as a session musician in Los Angeles, recording soundtracks for television and film. He came to the task of writing film scores, therefore, with a deep understanding of how music can shape the viewer’s experience of a drama.

The Star Wars Soundtrack

At the heart of Williams’s soundtrack is a series of themes—about eleven per film—that represent individual characters, settings, or ideas. The viewer doesn’t need a guide to these themes. Instead, one quickly connects music with onscreen action as themes return throughout the films. Here, we will examine themes associated with Darth Vader, Luke Skywalker, Princess Leia, Yoda, and the Force. Williams carefully crafted each of these themes to represent the character or idea, and they are used both to amplify the onscreen action and to enrich the storytelling.

Listening Guide: “Main Theme” from Star Wars

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’0″ | intro | The opening fanfare features the brass section. |

| 0’06” | A | This triumphant trumpet melody contains multiple upward leaps. |

| 0’17” | The A theme is repeated with changes in the accompaniment. | |

| 0’26” | B | This melody features the strings. |

| 0’48” | A’ | When the A material returns, the melody is played by violins and horns, giving it a different character. |

| 1’10” | End of listening guide |

We will begin with Luke Skywalker’s theme (officially titled “Main Theme”),

which is first heard over the opening title. This is clearly the music of a hero. The opening fanfare suggests royalty, while the duple meter and moderate tempo tells us that this is a march. This, in combination with brass-heavy instrumentation, suggests a military character—a good representation of the Rebel Alliance. The melody soars into the upper range, confirming Skywalker’s confidence and authority with a series of leaps up to the high tonic scale degree. (This is the first and most important note of the scale on which the melody is built.) Trumpets, with their bright timbre, are more prominent than the other brass instruments. And, of course, Skywalker’s music is in the major mode. In addition, this theme has more emotional depth than Darth Vader’s. It is in a three-part form, which might be described as a b a’. While the a section has the characteristics described above, the b section features the string section, thereby introducing a warmer timbre and indicating that our hero has a human side. Finally, the fact that we hear Skywalker’s theme over the opening title tells us from the start who is going to emerge from this conflict victorious.

Listening Guide: “The Imperial March (Darth Vader’s Theme)” from Star Wars

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’0″ | intro | The strings and percussion lay down a pattern of dotted rhythms suggesting a slow, militaristic march. |

| 0’09” | A | The trombones and trumpets play a low, ominous melody. |

| 0’18” | B | This section of the melody begins with a leap to the high range followed by a twisted chromatic descent. |

| 0’28” | B’ | The repetition of B’ concludes differently. |

| 1’10” | End of listening guide |

The theme that represents the villain, Darth Vader, has many of the same characteristics. It, too, is a march (the theme is entitled “Imperial March”), and it features similar instrumentation. However, this theme is in the minor mode, which lets us know that this is the bad guy. The fact that the melody is played in a low range makes the music ominous, while the chromatic pitches and unusual harmonies make it mysterious. Darth Vader’s theme is forceful and threatening, perhaps even unstoppable, but it is not heroic.

The other themes are similarly suited to their subjects. Leia’s theme opens with a winding chromatic melody in the flute and oboe before unfolding into an expressive melody for french horn with muted strings in the background. The music suggests seduction and romance, while largely ignoring her role as an action hero (although there is a historical connection between the horn and heroes of the opera stage). Yoda’s theme is heard in the cellos and oboes with a peaceful accompaniment of strings, bassoons, and harp. The instrumentation resonates with his life in the woods, while the simplicity of the melody communicates his character. Both Leia’s and Yoda’s themes are heard at the same moderate tempo—an indication of romance in one case and peace in the other. Perhaps the slowest theme is that used to represent the Force, but now the tempo signifies inevitability and power. The theme itself is in the minor mode, not because it is tragic but because it is serious. It starts with a lone french horn, supported by tremolo in the strings, but grows dramatically in volume to embrace the whole orchestra.

“Princess Leia’s Theme” from Star Wars

Composer: John Williams

Performance: The Utah Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Varujan Kojian (1983)

“Yoda’s Theme” from Star Wars

Composer: John Williams

Performance: London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by John Williams (1980)

“The Force Theme” from Star Wars

Composer: John Williams

Performance: London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by John Williams (1980)

This has been a fairly technical description of each theme’s attributes, but the character of the music is easy to perceive without specialized knowledge. It is worth a reminder, however, that our understanding of what music expresses is determined by our own cultural contexts. This music builds on centuries of stylistic development and depends on each listener’s lifetime of experience. We understand what it is trying to communicate because we dwell in the same musical world as the composer. Sound, however, seldom has objective meaning. We recognize the sounds of a military march because we have heard one somewhere else. We know that swelling strings signify romance because we have seen a hundred other movies, which in turn build on older theatrical traditions. A listener from a culture that had no military bands and in which, say, organ music was understood to signal romance would not make these connections.

Richard Wagner, The Valkyrie

We are now going to explore that cultural context. John Williams was well educated in the Western concert and theatrical traditions. He served in the U.S. Air Force Band from 1952 to 1955, during which time he played piano and brass, arranged music, and conducted. His piano degree from the Juilliard School in New York City came with a thorough grounding in music history. And his decades recording film and television scores as a session musician in Los Angeles allowed him to become deeply familiar with the conventions of the screen.

Our examples, however, will come not from television or movies but from older traditions of theatrical music. We will begin with an example from the opera repertoire. In the European tradition, opera is a staged work of music theater, complete with costumes, sets, and dramatic plot twists. Most operas employ an orchestra to accompany the stage performers, who often sing throughout. While Richard Wagner’s style and melodies certainly influenced Williams’s work (the “Imperial March,” for example, is clearly derived from a theme Wagner wrote to represent a magical helmet known as Tarnhelm), we will focus here on Williams’s use of a technique that Wagner perfected: the technique of assigning a unique theme to each character, object, place, and idea in a drama. Wagner called such a theme a leitmotif.

This theme by Richard Wagner bears a clear resemblance to Williams’s “Imperial March.”

Wagner’s Career

Before examining Wagner’s music, some biographical context is called for. It is possible that Richard Wagner (1813-1883) has had a greater impact on the development of Western art music than any other composer. For such a towering figure, however, he got off to a very slow start.

He did not exhibit any particular talent as a child and never became an accomplished performer. In his twenties, he dedicated himself to the composition of operas, although it was many years before he made a success of the endeavor. In 1839 he actually had to crawl through the gutters of Riga to escape his creditors after having his passport confiscated by the municipal authorities. Then in 1849 he became involved in an attempt to overthrow the Dresden government. He not only helped to plan what is now known as the May Uprising, but actually participated, throwing grenades in the street. After the uprising failed, Wagner fled to Switzerland, where he remained in exile for most of a decade.

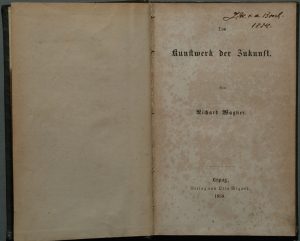

In Switzerland, Wagner shifted his attention from practice to theory. He quit writing music for several years and instead wrote about music. In one 1849 essay, “The Artwork of the Future,” Wagner theorized a Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total artwork,” that would bring together all art forms—music, dance, gesture, poetry, image—into a single, ideal medium of artistic expression. Naturally, he imagined himself as the artist who was most capable of achieving this fusion. To prove the power of his ideas, he set to work on a monumental cycle of music dramas that would take him decades to complete. In a highly unusual move, Wagner not only wrote the music for these operas but also developed the narrative, wrote the libretto (the sung text), and even designed the theater in which the operas were eventually premiered. The project took him decades to complete, and the entire cycle was not premiered until 1876. By this time, Wagner had returned to Germany under the patronage of the King of Bavaria, who admired his work and offered him permanent financial support. The King also financed the construction of a grand opera house (the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth) to Wagner’s specifications. It was there that the complete cycle was finally staged.

The Ring Cycle

Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelungs (German: Der Ring des Nibelungen)—or, as it is now known, the Ring Cycle—consists of four massive operas and takes about fifteen hours to perform. The story derives from Norse mythology, which Wagner understood to describe the ascent of his own German race. The operas enact a prolonged struggle between the gods and the humans. The gods are ruled by Wotan (the German version of the more familiar name Odin), who seeks to consolidate their power, but he is finally defeated by the human Siegfried. The story begins with the forging of a powerful ring out of gold extracted from the Rhine river and ends with the return of the ring to the river, the burning of Valhalla, and the flooding of the Rhine. These catastrophes mark a new age of human rule—the Norse myth of Ragnarök.

Like John Williams and George Lucas, Wagner relied on centuries of cultural history in crafting his masterpiece. The story outlined above is not original. His approach to setting that story to music was also not original, although he took preexisting techniques to new heights. To begin with, Wagner expanded the size of his orchestra, introducing new instruments into the brass section. These instruments—which included the bass trumpet, contrabass trombone, and a euphonium-type device now known as the “Wagner tuba”—allowed him to produce a more subtle variety of timbres for the creation of diverse sound worlds. His musical style, like that of other composers of the time, was highly varied and expressive, although many of Wagner’s contemporaries felt that his music set the bar for intensity of emotional content. Finally, Wagner adapted and transformed a practice that had long been common in opera: the use of recurring melodic themes (leitmotifs) to help tell the story.

If a listener sits through Wagner’s entire fifteen-hour drama, they will hear hundreds of leitmotifs, most of which are frequently repeated. Some span all four operas, while some are restricted to an act, or even a single scene. Each is connected to an important element of the drama, and each is introduced along with that element. The first time Wotan picks up his spear, for example, we hear a forceful, march-like descending melody in the brass. This music then returns every time we see the spear or hear a reference to it. Wagner’s leitmotifs are often melodically connected to each other, such that themes representing related ideas or characters sound similar to one another. The leitmotifs can also be transformed as the power of an idea or object shifts over the course of the story. Most importantly, however, the leitmotifs can be used to communicate information to an audience that is not included in the libretto or onstage action. We will see this principle at work in our example.

This video, produced by the brass section of the Metropolitan Opera orchestra, presents several important leitmotifs and demonstrates how they can be transformed to communicate meaning.

The Valkyrie

Listening Guide: “Wotan’s Farewell” from The Valkyrie

| Time | Leitmotif | What to listen for |

| 7’53” | Powerful destiny | Heard in the trombones as Wotan prepares to put Brünnhilde into an enchanted sleep. |

| 7’59” | Renunciation | Heard first in the horn and continued in the oboe. |

| 8’06” | Wotan announces that he is about to strip Brünnhilde of her immortality. | |

| 8’40” | Magic sleep | Heard first in the woodwinds, then the strings. |

| 9’26” | Innocent sleep | Heard in the strings. |

| 9’36” | Wotan’s grief | Heard in the strings in combination with “Innocent sleep.” |

| 11’10” | Powerful destiny | Heard in the trombones in combination with “Innocent sleep.” |

| 11’35” | Wotan’s spear | Heard in the low brass. |

| 11’43” | Loge as fire | The collection of leitmotifs related to Loge as fire enter the texture. |

| 11’45” | Wotan calls forth Loge, the demigod of fire. | |

| 12’05” | Wotan’s spear | Heard in the low brass. |

| 12’11” | Ambivalent Loge | We hear hints of this leitmotif interwoven with “Loge as fire.” |

| 12’44” | Ambivalent Loge | Heard in the woodwinds. |

| 13’19” | Magic sleep | This version of “magic sleep” moves at a much quicker tempo than that heard at 8’40” |

| 13’33” | Innocent sleep | Heard in the woodwinds. |

| 13’43” | Siegfried’s heroism | To the melody of “Siegfried’s heroism,” Wotan declares that any man who fears his spear will be incapable of crossing the flames. |

| 14’11” | Siegfried’s heroism | Repeated in the brass. |

| 14’36” | Wotan’s grief | Heard in the cellos. |

| 15’25” | Powerful destiny | Heard twice in the low brass. |

We are going to take a look at the final scene (Act III, Scene 3) of the second opera, The Valkyrie (German: Die Walküre). This scene contains two characters, Wotan and his favorite daughter, Brünnhilde. At this point in the drama, Brünnhilde, daughter of the god Wotan, has disobeyed her father’s orders by interceding on behalf of the humans Siegmund and Sieglinde. Despite her efforts, Siegmund is killed, and Brünnhilde is left to face Wotan’s fury. The punishment for disobeying the ruler of the gods is death, but Wotan takes pity on Brünnhilde, whom he loves dearly, and instead declares his intention to strip her of her immortality and powers and put her into a magical sleep on top of the mountain. He conjurs Loge, the demigod of fire, to erect a ring of flames around Brünnhilde, and declares that only a hero who does not fear his spear will be able to pass through the fire and wake his daughter.

This scene, which lasts less than twenty minutes, contains twenty-one separate leitmotifs. Indeed, the listener hears virtually no music that cannot be classified as a leitmotif. Most of the themes in this scene were introduced in the first opera and have been heard many times, although some do not return after this scene. Four themes, however, are introduced in this scene and proceed to play an important role in the remaining operas. Although various music scholars have counted and named Wagner’s leitmotifs in different ways, we will use the descriptions supplied by Roger Donington in 1963.

According to Donington, the scene in question contains the following leitmotifs: love as fulfillment, Wotan frustrated, powerful destiny, unavoidable destiny, Valkyries as animus, Valhalla, Wotan’s spear, relinquishment, Volsung as destiny, the love of Siegmund and Sieglinde, downfall of the gods, the curse, Siegfried’s heroism, sword as manhood, magic sleep, innocent sleep, ambivalent Loge, Wotan’s grief, renunciation, and Loge as fire (two different versions). As you can see, these themes connect with a wide variety of dramatic elements. Some are straightforward representations of objects or places, while others embody abstract concepts. All enrich the drama and aid in telling the story.

Like Williams, Wagner did not randomly pair themes with objects and ideas. Each leitmotif expresses meaning in sound. We will examine a few of the themes used in this scene before seeing them in action. The music associated with “Loge as fire,” for example, is meant to capture the characteristics of flame. This passage features high-pitched instruments with bright timbres, such as the flute, and the sharply-articulated melody leaps about. The music almost sparkles. Swells and ebbs in the music—created using rising and falling dynamic levels and pitches—represent the unpredictable spread of fire across the ground. (This kind of music has long been associated with wind and storms.) In contrast, both of the “sleep” leitmotifs are slow and peaceful, and they feature the soothing sounds of strings and harp. “Magic sleep” consists of a gradual chromatic descent that comes as close as music can to representing the act of falling asleep. “Innocent sleep,” on the other hand, is easily recognized as a lullaby, with its rocking rhythms, lilting melody, and stable harmonies.

The “Loge as fire” and “Ambivalent Loge” leitmotifs, both heard in this passage, capture the characteristics of a leaping flame.

The “Magic sleep” leitmotif suggests the act of falling asleep.

The “Innocent sleep” leitmotif sounds like a lullaby.

Wagner used his large brass section to represent strength and power. “Wotan’s spear,” which features the trombones and tubas, marches confidently down a scale into the very low range. “Siegfried’s heroism” begins with a confident leap up to the tonic and often grows in volume. (Many listeners observe that this leitmotif closely resembles John Williams’s theme for “the Force.”) “Powerful destiny,” which is heard throughout the scene, consists of a simple but surprising shift from one harmony to another. Wagner weaves all of these leitmotifs together into a tapestry of orchestral and vocal sound.

The “Wotan’s spear” leitmotif is brash and aggressive.

The “Siegfried’s heroism” leitmotif represents confidence and bravery.

The “Powerful destiny” leitmotif is simple but mysterious.

Finally, this scene—which is often referred to as “Wotan’s farewell”—exhibits one of the most significant powers of the leitmotif: its ability to foreshadow events yet to come. In the final moments of the scene, Wotan declares that only a hero who does not fear his spear will be able to pass through the flames and wake Brünnhilde. He sings this declaration to the melody of “Siegfried’s heroism,” which is then echoed by the full orchestra in a resounding climax. At this point in the story, however, Siegfried has not even been born. Sieglinde has only just learned that she is pregnant with him, and he will not appear until the next opera. At the same time, the theme is not new. It has been in use since earlier in this opera to foreshadow the appearance of a human hero, and it will be heard nine times in the next opera. When we hear this music, therefore, we know exactly who is going to wake Brünnhilde, even though Wotan—who sings the melody—does not.

Concerns

There is no question that Wagner’s Ring operas have been both influential and successful. They are staged in countless opera houses around the world every year, often at great expense. The most lavish cycle to date was produced at New York City’s Metropolitan Opera House in 2012 at a cost of $19.6 million. Every year, fans travel to the Bayreuth Festival in Germany to see the Ring and other Wagner operas staged in the theater that the composer himself designed. At the same time, some critics argue that we should no longer produce these operas or listen to Wagner’s music. Their argument is not that the music is bad, but rather that the composer’s ideology is so repugnant as to merit the erasure of his art.

Wagner’s anti-Semitic views were widely known during his lifetime. In an article entitled “Jewishness in Music” (1850), he argued that Jewish composers were incapable of producing profound musical expression, and that their attempts to do so were damaging to the progress of art. Furthermore, he claimed that Jewish artists lacked the capacity to recognize or represent authentic German culture. Although Wagner first published the article under a pseudonym (presumably to make his attacks against other composers seem less personal), in 1869 he republished it under his own name, and with a long addendum reflecting the artistic and political developments of the intervening decades. Wagner’s views provoked considerable resistance among his contemporaries, but they were later embraced by the Nazi Party. Indeed, Adolf Hitler would become Wagner’s most infamous admirer.

There are also concerns about the content of Wagner’s music dramas. While the Ring is not overtly anti-Semitic, it expresses an ideology of nationhood that tacitly excludes all but the ethnically pure “German” of Wagner’s imagination. Stripped of their mythology, the Ring operas tell the story of a human race that rises to a position of world dominance. For Wagner, this was the German race, and the German race did not include Jews.

For these reasons, Wagner’s music is unofficially banned in the nation of Israel, while music lovers around the world hold his work in disdain and choose not to program or consume it. The debate over whether we can separate an artistic work from its creator, however, is far from settled. Should the sins of the artist be visited upon the art? Can we enjoy music, films, or paintings that we know to have been created by reprehensible individuals? Does it matter that Wagner died many years ago, and can neither profit nor suffer as a result of our consumption decisions? Does support of Wagner’s art suggest support of his ideas? We are forced to grapple with these questions not only in the case of Wagner but every time that the creator of beloved cultural products is discovered to have committed hateful actions.

Gustav Holst, The Planets

While John Williams’s approach to creating the Star Wars soundtrack can be traced through Wagner, his music is more heavily influenced by other composers and works. The most frequently noted of these is the orchestral suite The Planets (1914-1916) by British composer Gustav Holst (1874-1934). The reasons for which Williams chose to borrow from Holst are simple enough to understand. Holst was one of the first composers to write music about outer space, and he did so with a dramatic flair that has kept this work in the repertoire ever since its 1920 premiere.

Holst and The Planets

Holst studied composition at the Royal College of Music in London, where he met with moderate success. He was not attracted to the life of a professional musician (Holst played the trombone), but he struggled to make a living as a composer. In 1903, therefore, Holst began teaching music in schools. Although he would write some of his most successful music for the orchestras he directed, he had little time in which to pursue his craft. Nevertheless, Holst continued to produce serious concert pieces and his reputation steadily grew.

Holst finally earned national attention in 1920, first with a work for choir and orchestra entitled The Hymn of Jesus and then with The Planets. The Hymn of Jesus paved the way for The Planets’ success by establishing for Holst a reputation as a mystic and spiritual composer. As we will see, these qualities are prominent in the orchestral suite. Although the entire suite was not premiered until 1920, Holst had been at work on it since 1913. He first wrote the music for two pianos, and produced the orchestral score only after the composition was complete.

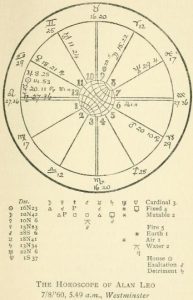

Much of Holst’s work as a composer can be traced to his personal interests. This is certainly true of The Planets. In 1913, Holst travelled to Majorca with a group of fellow artists, who introduced him to the study of astrology. Holst became fascinated and immersed himself in the work of British astrologist Alan Leo, reading his book What Is a Horoscope and How Is It Cast?. The idea of composing an orchestral suite came to him almost immediately, and he began sketching the first movement, “Mars,” that same year.

Holst’s intent was to capture the astrological significance of each of the planets, as described by Leo. He was interested in the specific characteristics bestowed on those who were born under the influence of each individual planet. At the same time, Holst was a composer first and an astrologer second. His primary concern was musical cohesion and expression. As a result, he frequently deviated from Leo’s prescription, and in the end used Leo’s writings merely as an inspiration for his own creative work.

It seems that Holstwas worried that audiences would not take his music seriously. An orchestral work inspired by celestial bodies, after all, might easily be dismissed as a mere novelty, especially when compared to the traditional symphonies that formed the core of the concert hall repertoire (see Chapter 7). For this reason, Holst first titled his suite Seven Pieces for Orchestra, only later changing it to The Planets. He added the individual movement names, indicating which planet the music is about, only just before the work was published. The descriptive titles qualify The Planets as program music, a term used to identify an instrumental composition that tells a story or paints a picture. Holst chose not to order the movements in order of their distance from the sun, instead swapping Mars and Mercury. The reason for this decision is clear enough: The music that Holst composed to depict Mars makes a great opener for the work.

The Planets was a massive success. It was immediately programmed by orchestras all over England and has since become one of the most familiar and most frequently performed pieces in the orchestral repertoire. All the same, Holst came to regret his biggest hit. He continued to develop and grow as a composer, and within just a few years he considered The Planets to be outdated. Critics, on the other hand, were disappointed when Holst’s new compositions did not sound like his original blockbuster. Although Holst went on to write many beloved works, he never matched the success of The Planets.

We will examine the first and last movements of Holst’s suite: “Mars, the Bringer of War” and “Neptune, the Mystic.” “Mars” served as a model for John Williams’s “Imperial March” in the Star Wars soundtrack, while “Neptune” seems to have had a general influence on Williams’s musical portrayals of space.

Mars

In astrological terms, the planet Mars is associated with confidence, self assertion, aggression, energy, strength, ambition, and impulsiveness. Leo described those born under the influence of Mars as “fond of liberty, freedom, and independence,” noting that they “may be relied upon for courage” and are “fond of adventure and progress” but are also “headstrong and at times too forceful.” In mythological terms, Mars is the ancient Roman god of war.

“Mars” from The Planets

Composer: Gustav Holst

Performance: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by James Levine (1990)

Holst seems to have combined these influences in his music, which is overtly militaristic. The staccato rhythms heard at the beginning are the rhythms of a military march. At first they are played by the entire string section using a special technique, known as col legno, for which players turn their bows upside down and bounce the wooden stick on the string. Later, the snare drum—an actual military instrument—plays the same rhythm, which is heard almost throughout the movement. There is something very strange about Holst’s march, however: It is in quintuple meter, with five beats per measure. It would be very difficult to actually march to this music.

Holst uses other strategies as well to communicate the character of Mars. The first melody we hear is low and ominous, consisting only of a rising gesture followed by a small descent. As the texture thickens, the volume increases and the melodic gestures seems more threatening. The introduction of trumpets and other brass instruments reinforces the militaristic flavor of the movement. In the middle section, the trumpets seem to be sounding battle calls. Finally, the whole movement comes to a crashing close with the strings and brass playing as loudly and violently as possible.

Neptune

Holst’s representation of Neptune, the final planet in his suite, is entirely different. This is natural enough, given Holst’s astrological mindset, for the influence of Neptune is associated with idealism, dreams, dissolution, artistry, empathy, illusion, and vagueness. Holst creates music, therefore, that captures these same qualities.

“Neptune” from The Planets

Composer: Gustav Holst

Performance: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by James Levine (1990)

We might begin with a discussion of timbre. “Neptune” includes a sound that is completely absent from the other movements: women’s voices. Holst includes two choirs of sopranos and altos, making for six separate vocal parts. The women don’t sing words, however, but are instead instructed to sustain long, open “ah” vowels. The singers therefore function in the same way as instruments, bringing an ethereal, transparent quality to the upper register of the orchestra.

Apart from the voices, “Neptune” calls for the same instruments as “Mars.” However, Holst deploys these instruments quite differently. He hardly uses the brass section at all, relegating them to low, sustained pitches in the background of the texture. Holst assigns the melody to wind instruments, with a preference for the airy sound of the flutes and the reedy timbre of the oboe and English horn. He also foregrounds the two harps and a percussion instrument called the celeste, which has a keyboard similar to that of a piano but produces the sound of bells.

The articulation in “Neptune” is completely unlike that heard in “Mars.” While “Mars” is characterized by abrupt, accented rhythms, the pitches in “Neptune” are sustained and connected. Interestingly, this is the only movement that Holst originally composed for organ instead of piano. He felt that the organ, which can sustain pitches indefinitely, was better able to capture his musical vision. While both “Mars” and “Neptune” are in quintuple meter, the differences in articulation and tempo (“Neptune” is much slower) means that the two movements have completely different effects on the listener.

Finally, we might say something about the melody and harmony. There are no catchy tunes in “Neptune.” Instead, the wind instruments and voices repeat floaty, circular melodies that don’t seem to go anywhere. “Neptune” is also not in any particular key. Instead, the music rocks back and forth between seemingly unrelated harmonies. All of this creates the sensation of being unmoored. It is hard to predict where the music is going, but easy to enjoy the beautiful sounds.

Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring

While the influence of Holst’s “Mars” is particularly evident (after all, we hear the “Imperial March” repeatedly in almost all of the films), Williams also tapped the musical language of another prominent composer working at the same time. This borrowing did not become one of the repeated themes in Williams’s score, but it is no less unmistakable. In addition, he borrowed for the same reason: Another composer of musical drama had already succeeded in setting the mood that Williams wanted to create: a mood reflecting uncertainty, suspense, and possible danger. Why reinvent the wheel?

The scene in question comes early in the first film, A New Hope (1977). The droids, R2D2 and C3PO, have landed on the desert planet Tatooine, where they argue and strike off in different directions. The setting is desolate and eerie, and the music serves to amplify our feeling of uncertainty about what is to come. We follow the path taken by C3PO, who doesn’t know where he is, where he is going, or what might happen to him. The music that accompanies his journey is similarly uncertain. Oscillating melodies in the winds and muted trumpets are paired with high sustained notes in the strings and chromatic interjections from the bassoon and clarinet. Low, ominous sounds from the brass and reeds suggest a lurking danger. The music is in neither the major nor minor mode, there is no sense of a “home” note (the tonic), and we are not provided with any conclusive musical gestures (cadences). Instead, the pitches seem to float about. There is no sense of direction or purpose. At the end of this brief scene, the music simply fades away.

In the context of Star Wars, we are talking about just over 50 seconds of music. Were it not for Williams’s borrowing, this scene would hold little interest. However, the work from which Williams extracted this brief passage of music was among the most influential of the twentieth century, and it is therefore worth exploring in order to understand why Williams chose this source, why the original work was composed in the first place, and how the dramatic intent of the two composers can help us to understand how music communicates meaning.

The passage adapted by Williams appears at the beginning of the second half of Igor Stravinsky’s 1913 ballet The Rite of Spring (French: Le sacre du printemps). Like Williams, Stravinsky needed music that would create an atmosphere of mystery and suspense. Both dramas are set in an undefined, distant past: Williams’s “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away,” Stravinsky’s amongst the pagan tribes of prehistoric Russia. The differences arise when we examine the scenes for which each composer is preparing the viewer. C3PO is about to be captured by traders, while Stravinsky’s characters are about to choose their victim for a virgin sacrifice.

Stravinsky and The Rite of Spring

Stravinsky wrote The Rite of Spring for a Paris audience (for whom Russia was indeed “far, far away”). Although Stravinsky was himself Russian, he had been living in Paris and writing ballets for three years. He was recruited for the job by Sergei Diaghilev, a wealthy Russian who had embarked on the quest of exporting Russian ballet to Paris. To do so, Diaghilev established a ballet troupe known as the Ballets Russes (that’s “Russian Ballet” in French). His troupe specialized in flamboyant stage presentations that were meant to dazzle Parisian theatergoers with exotic stories, costumes, and music. When Stravinsky first agreed to join Diaghilev, he did so only because he had few other opportunities. He was unknown in Russia and had just begun his career in music. In accordance with Diaghilev’s scheme, he participated in the production of a series of ballets with Russian themes. The first was The Firebird (1910), which combined various Russian folk tales with a typically Russian musical language. The second, Petrushka (1911), was set at a fair in the Russian countryside. Rite of Spring carried on this trend to a degree, but it was also startlingly new in several ways.

Like all ballets, The Rite of Spring was developed by an artistic team. The idea for the ballet was conceived jointly by Stravinsky and the painter Nikolai Roerich. Roerich, who was an expert on pre-Christian Slavic history, also designed the ballet’s scenario (how the story unfolds), costumes, and sets.

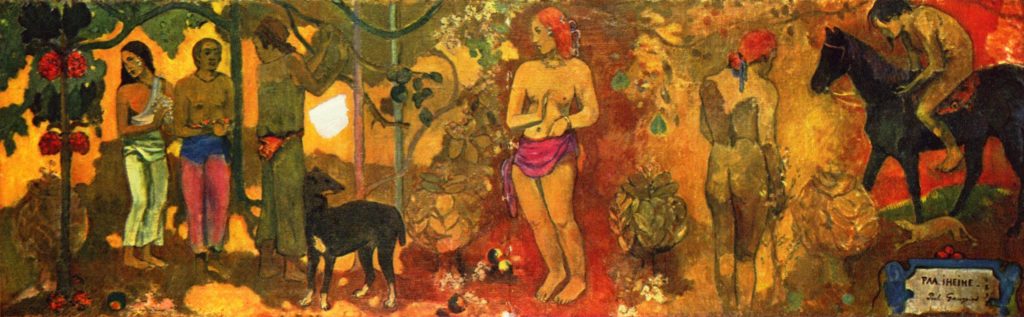

The choreographer—that is, the person who planned and taught the actual dance steps—was Vaslav Nijinsky, a famous dancer who had been part of the Ballets Russes since its founding and first performances in 1909. Working together, these three men put together a show that they knew would turn heads. At the same time, their ideas weren’t entirely new. Artists working in Paris and beyond had for decades been preoccupied with so-called “primitive” cultures, which were believed to reveal fundamental truths about the human condition. At the same time, paintings of halfnaked island dwellers, such as those produced by Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), were enticing and exotic. They allowed momentary escape from the constraints of Western society as they invited viewers to gaze upon supposedly innocent and uninhibited subjects.

Unlike most ballets, The Rite of Spring doesn’t tell a particularly coherent story. It is in two parts. Over the course of Part I, which is entitled “Adoration of the Earth,” members of Roerich and Stravinsky’s imagined pagan tribe engage in a variety of rituals and games. In Part II, “The Sacrifice,” a young girl is selected as the sacrificial victim. She dances herself to death in the final minutes of the ballet.

The Rite of Spring caused something of a stir at its premier. In what has since been described as a “riot” (although historical evidence indicates that this characterization is overblown), audience members reacted with consternation to what they saw and heard. To fully understand this response, we need to examine context, precedent, and the musical and visual elements of the ballet.

To begin with, The Rite of Spring was not the evening’s sole entertainment. It was the second ballet on a double bill. The first ballet, entitled The Sylphs (French: Les Sylphides), was a classic from the Russian ballet repertoire. Diaghilev had included it in the first Paris season of the Ballets Russes, so the audience knew what to expect—and The Sylphs, which featured music by the 19th-century composer Frederic Chopin, was just the kind of thing Parisians wanted to see. The action consisted of elegantly-clad dancers cavorting gracefully about the stage. Viewers admired the beauty and poise of the artists.

The most disturbing element of The Rite of Spring, therefore, was not the plot or music but the dancing. Nijinsky had abandoned the graceful gestures and acrobatic leaps of traditional ballet. Instead, he had the dancers stomping around the stage on flat feet, with hunched backs and awkwardly protruding limbs. He did so in an attempt to capture the primitive and raw aesthetic of the subject matter, as he perceived it. Of course, all of this came out of Nijinsky’s imagination. For him, the idea of ancient pagan tribes served as an inspiration to try something new and daring. He had no way of knowing how his subjects might have actually danced.

This 1987 performance by the Joffrey Ballet attempted to recreate the original appearance of The Rite of Spring, including the costumes and choreography.

Nijinsky’s choreography was complimented by Roerich’s costumes. Instead of delicate tutus revealing stocking-clad legs and pointe shoes, Roerich’s dancers appeared in cumbersome, floor-length dresses and cloaks. The women wore flat shoes and had long braids instead of neat buns. Audiences were thereby denied the opportunity of admiring the female form—a luxury that was central to the enjoyment of ballet.

Ninjinsky was also responding to Stravinsky’s music, which was unlike anything that had been heard in the theater before. The music did not contain lyrical melodies or compelling harmonic progressions. It did not express feelings of yearning, or heartbreak, or passion—the typical “human” emotions of the stage. Instead, it was alternately mechanistic, mysterious, threatening, and frenzied. Stravinsky’s ostinatos and pounding rhythms inspired Nijinsky’s similarly repetitive and rhythmic choreography. To understand how the music worked, we will look at two examples: the “Introduction” to Part II (later borrowed by Williams) and the “Sacrificial Dance” that concludes the ballet.

Part II: Introduction

Part II: “Introduction” from The Rite of Spring (starting at 16:34)

Composer: Igor Stravinsky

Performance: London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Simon Rattle (2017)

The “Introduction” opens with a dissonant cluster of notes. The oboes and horns hold their notes, while the flutes and clarinets oscillate between pitches. What we hear does not suggest any particular key, major or minor. Stravinsky achieves this by having the instruments play in a number of different keys at the same time, a technique known as polytonality. The result is that the listener has no sense of direction or grounding. This disorienting effect serves to introduce a dramatic world with mysterious and unfamiliar characteristics.

There is no discernable melody for a long time—just the ebb and flow of Stravinsky’s unusual sound colors. When a recognizable tune finally appears in the violins, it is played using harmonics, a string technique that causes pitches to sound much higher than usual and gives them an eerie quality. The melody uses only four pitches (it is quadratonic), and was probably inspired by Russian folk music.

Near the middle of the movement, the music changes. Two trumpets introduce a new melodic idea, changing pitches in alternation with one another. Starting at this point, Stravinsky employs a compositional technique that is typical of The Rite of Spring: He begins to build up layers by bringing in the sections of the orchestra one by one, each with its own characteristic melodic motif. First the strings begin to play quick rhythmic figures with repeated notes. Then the clarinets and violins enter with upward melodic swoops. The musical texture slowly gets denser and busier, the swoops coming with gradually increasing frequency. This ends with the return of the quadratonic melody in the horns as Stravinsky transitions into the next movement.

The “Introduction” has a pulse throughout, but the pulse is unevenly grouped into measures and phrases. For this reason, it is impossible to predict when a melodic or harmonic change is going to come. The effect is to leave the listener on edge, never certain what is going to happen next. Stravinsky uses this technique in every movement of The Rite of Spring, but to various ends. While uneven phrasing makes the “Introduction” seem vague and mysterious, it makes the Sacrificial Dance,” which concludes the ballet, sound violent and threatening.

Part II: Sacrificial Dance

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’0″ | A | All parts of the orchestra engage in an unpredictable back-and-forth characterized by constant meter changes. |

| 0’25” | B | The texture is reduced to an uneven rhythm. |

| 0’37” | Brass interjections begin. | |

| 0’52” | Strings enter to supplement the uneven rhythms and intensity builds. | |

| 1’21” | Following a climactic point, the texture is reduced to a minimum and the process repeats. | |

| 1’27” | Brass interjections begin again. | |

| 1’35” | A whirling figure in the strings intensifies the music. | |

| 1’43” | A’ | Nearly identical to A. |

| 2’08” | C | The texture is dominated by brass and percussion. |

| 2’40” | A” | Brief return to A material. |

| 2’46” | C’ | Return to C material. |

| 3’07” | A”’ | Rhythmically, this passage can be recognized as a version of A, although the range, harmonies, and instrumentation are different. |

| 3’54” | Coda | The dance ends with an ascending flute run and a final cacophonous chord. |

The “Sacrificial Dance” is in rondo form, in which a primary melody returns throughout. It might be summarized as A B A’ C A’’ C A’’’ with a brief coda, although in reality it is somewhat more complicated. However, using these letters will allow us to briefly discuss each section.

The A section is the most rhythmically jarring. The strings and winds play accented, dissonant chords in alternation with one another, culminating each time in one of two melodic figures: a short series of descending pitches or a series of repeated pitches with one higher outlier. Both figures are loud, accented, and aggressive, and, due to the rhythmic irregularity, it is impossible to predict when they will be heard.

The B section is significantly more subdued, although no more predictable. The strings provide an underpinning of irregular chords, while brass instruments periodically interject with accented, descending melodic fragments. The music builds in intensity before reverting to its original character. It then builds once more before the return of the A material (labelled A’ to indicate the fact that the music is slightly different).

The C section features a wide variety of percussion instruments, including timpani and cymbals. Over these, various brass instruments enter with heavily accented melodies. Again, the music gets louder and more intense as it builds into yet another return of the A material. A’’, however, is very brief, for it is almost immediately interrupted by the continuation of C—now with even greater intensity.

The final return of the opening material as A’’’ sounds significantly different, for it employs different sets of pitches. However, the rhythmic character is the same. Once again Stravinsky builds the intensity of the music by alternating between his melodic ideas with increasing frequency, never establishing a pattern that will allow the listener to get comfortable. Finally, an ascending glissando in the flute, followed by a loud final chord, indicates that the dancing girl has collapsed.

Ragtime and Dixieland Jazz

We will consider one more of Williams’s borrowings. This time, however, we will be giving primary consideration to style, for Williams was influenced by a pair of musical traditions—specifically, those of ragtime and Dixieland jazz—rather than by a specific composition. Before we can examine the borrowing, however, we need to take a step back and consider the different ways in which music works in film.

Underscoring vs. Source Music

Think back on the scene we used to introduce the borrowing from The Rite of Spring. Was C3P0 able to hear that music? Did the eerie, discordant sounds tell him anything about what lay in store? Most viewers would agree that he heard nothing other than the wind across the desert sands. That music was only for us, the moviewatchers, not for the character in the scene. Indeed, most of the music in Star Wars seems to be only for the viewer. Darth Vader does not keep an orchestra on hand to play his entrances, and Yoda certainly doesn’t have one out in the swamp. When we hear music while watching the movie, we understand that its purpose is to amplify emotion and help tell the story. It is not actually a part of the story.

In the film industry, this technique is known as underscoring. It has been in use since the silent era, when theater organists and orchestras used to provide live music to accompany moving pictures that did not have dedicated soundtracks. Of course, this kind of music played a role in theatrical presentations long before movies came on the scene. Operas and ballets also include music that the characters on stage cannot hear, but that is nonetheless essential to the storytelling. In general terms, this is termed non-diegetic music.

If there is non-diegetic music, there must be diegetic music—music that the characters in the drama can in fact hear. In film, this is called source music, because the source of the sound is usually visible on screen. Almost every film and television show combines these two types of music. When a character is listening to the radio, or playing the guitar, or attending a concert, or dancing in a club, you are hearing source/diegetic music. When you can’t see where the music is coming from and have good reason to doubt that it is audible to the onscreen characters (for example, when you hear an orchestra while watching someone walk down the street alone), you are hearing underscoring/non-diegetic music.

Often, it is not obvious whether the music we are hearing is diegetic or nondiegetic. In the case of the “Imperial March,” for example, it is reasonable to believe that the Imperial Army might in fact have a band present that might in fact play a march. Many militaries have such musical ensembles, and even though we never see a band, we cannot prove that one is not present. At the same time, we can doubt that such a band would contain the full range of winds and strings that we hear in the soundtrack. Perhaps the Imperial forces are indeed hearing music—just not the same music that we are hearing. (The opposite can also occur. In one famous scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1956 film The Man Who Knew Too Much, a live concert performance also serves to underscore the unfolding drama, such that we cannot confidently label the music as either diegetic or non-diegetic.) These problems become much more frequent and difficult to solve in musical theater genres, as we will see later.

Both diegetic and non-diegetic music can be equally important to the telling of a story, although each type tends to serve a different purpose. The most striking use of diegetic music in Star Wars occurs forty-five minutes into the first film, when the protagonists arrive at a bar to meet with Han Solo. In this scene, known popularly as the “cantina scene,” we both hear and see a band playing a catchy tune. Because we see the performers, we can be quite certain that the onscreen characters are able to hear the music as well. At the same time, the music makes sense in this context. It is natural for a bar scene to contain a band playing lively music in a popular style.

The style itself speaks to us. Although Williams is not borrowing from a specific composition in this case, he is borrowing from a rich tradition of African American dance music. Specifically, he is reinterpreting the rhythms and textures of two related dance music styles from the early twentieth century: ragtime and Dixieland jazz.

Ragtime

Ragtime was developed in the 1890s by African American piano players working in Midwestern entertainment venues. These highly-skilled musicians began to take a new approach to performing well-known tunes. A ragtime pianist would keep a steady beat with his left hand, alternating between high and low pitches, while performing complex syncopated rhythms with the right hand. (A syncopated rhythm includes accented notes that do not line up with the underlying pulse, but instead seem to fight against it.) While any melody can be “ragged” (that is, performed in this manner), African American pianists soon began composing and publishing original pieces with “ragtime” in the title or description.

The style quickly caught on across the nation. Its syncopated rhythms were fresh and exciting, and they made the listener want to dance. By 1910, ragtime rhythms and references were common in all types of popular music. At the same time, white Americans exhibited a great deal of concern about the influence of ragtime, which was associated with establishments where alcohol was served and the opposite sexes mingled freely. It was believed that the music’s enticing rhythms were so powerful that they might lead young people to commit immoral acts. Most importantly, ragtime was the first in a long line of African American styles to have a major impact on mainstream popular music, and it was therefore perceived as a threat by white cultural powerbrokers.

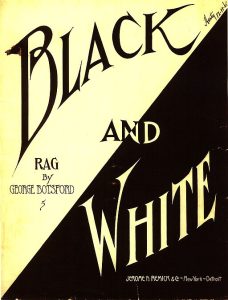

George Botsford/Winifred Atwell, Black and White Rag

We will take a closer look at Black and White Rag (1908), a composition by the Iowa pianist George Botsford (1874-1949). Like all rags, this piece is in a form derived from that of 19th-century marches. This approach to organizing music is based on the repetition of several distinct melodies, each of which is heard twice upon being introduced and then may or may not return later in the piece. The form of Black and White Rag can be summarized as follows: intro A A B B A C C B’. As you can see, the A melody returns after the introduction of B. The B melody then returns (in modified form) after we hear C. The result is a musical work that balances repetition with contrast. The listener is able to identify familiar melodies as they return, but is kept from becoming bored by the regular introduction of new melodies.

| Time | Form | Source for the passage |

| 0’0″ | Intro | Botsford |

| 0’04” | A | Botsford |

| 0’20” | B | Botsford |

| 0’36” | A | Botsford |

| 0’52” | Transition | Atwell |

| 1’01” | D | Atwell |

| 1’16” | E | Atwell |

| 1’32” | F | Atwell |

| 1’48” | Intro’ | Botsford/Atwell |

| 1’52” | B | Botsford |

| 2’07” | A | Botsford |

| 2’24” | Outro | Atwell |

Ragtime piano compositions were never intended to be performed exactly as written. A published composition in this genre should be understood as a set of guidelines for performance. The composer supplies the basic material, but the performer is invited to reorganize and elaborate upon that material. The recording selected for this text was made in 1951 by the Trinidadian pianist Winifred Atwell (1914-1983). It proved a hit, selling millions of copies in the UK and launching a craze for Atwell’s style of ragtime piano playing. Atwell prefered the sound of an authentic “honky-tonk” piano, as heard in this recording. This is not a specific type of instrument, but rather a general aesthetic that is associated with the sound of early-20th century barroom pianos. Such instruments were generally cheap, damaged, and out of tune. The piano in this recording has a tinny quality, while the multiple strings that are struck each time the player depresses a key are not in tune with one another.

Atwell takes a typically improvisatory approach to her performance of Botsford’s composition. She plays his introduction and A section essentially as written, although she does not repeat the A after the first time through. Then she plays the B section, followed by a repeat of the A section. Atwell omits Botsford’s C section, however, and instead interpolates her own material. The new music, which includes several contrasting phrases and transitional passages, fits well within the performance but bears no relation to what Botsford wrote. To conclude, she plays the B and A sections once more, adding a final tag of her own creation. Atwell’s performance, therefore, can be diagrammed as follows, with her original contributions in brackets: intro A B A [trans D E F intro’] B A [outro]. In sum, therefore, this is a performance of a piece composed half by Botsford and half by Atwell.

The syncopated, danceable rhythms of ragtime are easy to hear in Williams’s barroom music for Star Wars. The texture of ragtime—regular pulses in the low range, lively melody in the high range—is also evident. The instrumentation, however, echoes that of another African American dance music tradition, one that burst onto the scene just as ragtime was becoming passé: Dixieland jazz.

Dixieland Jazz

The style that would come to be known as Dixieland jazz developed in New Orleans in the early years of the twentieth century. Like ragtime, Dixieland jazz was heavily influenced by marching band music.

Street bands provided an important form of entertainment in the city, and formal ensembles regularly processed between the various neighborhoods. Less disciplined musicians, known as “second line” players, would tag along behind the bands, improvising syncopated melodies on top of those being played by the ensemble. This practice resulted in a new performance style, and small groups of musicians began gathering together to play syncopated music on traditional band instruments—usually clarinet, trumpet, trombone, and tuba, with banjo to provide the rhythmic underpinning. Dixieland jazz is also sometimes referred to as polyphonic jazz, due to the fact that all of the musicians play independent melodies at the same time. The term polyphonic means “many sounds,” and is used to describe music in which all parts carry melodies of equal importance.

One of the first great Dixieland band leaders was the cornet player Joseph Nathan “King” Oliver (1881-1938). Despite having established a formidable reputation in New Orleans, King Oliver moved to Chicago in 1918, hoping to secure a better life for himself and his family. He was not alone: millions of other African Americans living in the post-bellum South made the same trip in what is now termed the Great Migration. In Chicago, King Oliver was able to recruit the finest players for his band. These included a young Louis Armstrong (1901-1971), who had also learned his craft growing up in New Orleans. Oliver played first cornet, while Armstrong played second cornet and slide trumpet. The other musicians in Oliver’s band were clarinetist Johnny Dodds, Honoré Dutrey on trombone, Lil Hardin (later Armstrong) on piano, Bill Johnson on banjo and string bass (in place of tuba), and Baby Dodds on drums. King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band quickly gained popularity, and the recordings that they began to release in 1923 sparked a national craze for jazz.

King Oliver, Dippermouth Blues

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’0″ | Intro | All the melody instruments play a descending arpeggio. |

| 0’07” | Head | All of the melody instruments contribute different parts to the main theme. |

| 0’43” | Solo 1 | The clarinet improvises a solo while the other instruments provide a stop-time accompaniment. |

| 1’19” | Solo 2 | All of the instruments improvise at the same time. |

| 1’37” | Solo 3 | The cornet player improvises with a plunger mute; other instruments are heard improvising in the background. |

| 2’29” | Solo 4 | All of the instruments improvise at the same time. |

One of King Oliver’s most influential compositions was Dippermouth Blues, which his group recorded twice in 1923 for two different record labels. We’re going to examine the first recording, made in April for Gennett Records. The way this recording was made had a significant impact on how it sounds. Before the electric microphone was invented in 1925, music was recorded using acoustic technology. The musicians would gather around a horn that looked much like those you see on old gramophones. Those who played quiet instruments would stand close to the horn, while those who played loud instruments would stand further away, sometimes behind a barrier. The sound waves that entered the horn would cause a stylus to vibrate, which would in turn carve a groove into a rotating wax cylinder. The limitations of this technology meant that certain sounds could not be recorded.

In particular, instruments and voices that were very high, very low, or very loud caused the stylus to skip and ruined the recording. This explains why we don’t hear string bass or very much percussion in this recording of “Dippermouth Blues.” A live performance would have been slightly different.

After a brief introduction, we hear an excellent example of the Dixieland style as both cornets, the clarinet, and the trombone all play unique melodies at the same time. It is impossible to say who has “the” melody, for the music being played by each instrument seems to be of equal importance. The various instruments also take turns emerging from the texture. At one moment the clarinet seems to stand out, while at another your attention is drawn to the trombone. After a while, the clarinet really does take the melody, while the other instruments play a repeated rhythm in the background. Later, the cornet similarly takes a lead role. Near the end of the recording, we once again hear the polyphonic texture that marks this style. This music is busy and complex, but in a way it is also simple. Its object, after all, is to make you want to dance. If you feel compelled to tap your foot or otherwise respond to its syncopated rhythms, then the players have accomplished their goal.

The title of this selection also provides us with valuable information. “Dippermouth” was simply a nickname for Louis Armstrong (a fact that has led some to believe that Armstrong wrote this tune, not Oliver). The term “Blues,” however, describes several important characteristics of the music we are about to hear. The blues was an influential style of African American popular music that emerged on the vaudeville stage and later flourished among musicians of the Mississippi delta region. There is much to say about the blues style, but here we will focus on two elements that found their way into Oliver’s composition. The first has to do with harmonies. Upon listening to “Dippermouth Blues,” you might notice that you hear the same chords pattern again and again. This pattern repeats every forty-eight beats (listen to the percussion), or—if we group those beats into measures—every twelve measures. What you are hearing is called the twelve-bar blues, and it provides the structure for most blues compositions.

The other element from the blues that we hear in this example is the blue note. All of the harmonies used in the twelve-bar blues chord progression are in the major mode, and the melodies therefore ought to be in the major mode as well. In the blues tradition, however, performers sometimes lower certain melodic notes (an act known as “blueing” the note). These are usually the third, fifth, and seventh degrees of the scale, although other notes can also be blued. Because of this, the melody occasionally clashes with the harmony as the music pulls alternately towards the major and minor modes. This gives the music a particularly expressive dimension and encourages the listener to get physically involved. Whether or not you can identify the blue notes in this recording, you certainly feel their impact.

When we examine John Williams’s use of ragtime and Dixieland styles in Star Wars, we see how music intended for a purely practical purpose—in this case, dancing—can be used to tell a story. Ragtime and Dixieland jazz are not storytelling genres, but their sounds communicate many layers of information to the modern listener. They suggest dancing, nightclubs, drinking, and excitement. They might also suggest the story of African American contributions to American popular music, or the historical eras from which these styles emerged. In this way, we might consider all music—not just film scores or theatrical works—to have storytelling potential.

Resources for Further Learning

Audissino, Emilio. John Williams’s Film Music: Jaws, Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and the Return of the Classical Hollywood Music Style. University of Wisconsin Press, 2014.

Berlin, Edward A. King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era. Second edition. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Brothers, Thomas. Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans. Reprint edition. W.W. Norton & Company, 2007.

Greene, Richard. Holst: The Planets. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Hill, Peter. Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

John, Nicholas, ed. Die Walküre (The Valkyrie). Overture Publishing, 2011.

Lehman, Frank. Hollywood Harmony: Musical Wonder and the Sound of Cinema. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Wald, Elijah. Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues.

Amistad, 2004.

Online

Frank Lehman, Complete Catalog of the Musical Themes of Star Wars: https://franklehman.com/starwars/

The Leitmotifs of Wager’s Ring: https://pjb.com.au/mus/wagner/

Not Another Music History Cliché!, “Did Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring incite a riot at its premiere?”: https://notanothermusichistorycliche.blogspot.com/2018/06/did-stravinskys-rite-of-spring-incite.html