Private: Unit 3: Music for Entertainment

7 Listening at Public Concerts

Esther M. Morgan-Ellis and Louis Hajosy

Most of us know what a concert is, even if we’ve never been to one. They are common across categories of music and always follow the same basic formula: members of the public assemble at a given time and place to hear a soloist or ensemble present a prepared program of music. Concerts always tend to be presentational in nature (that is to say, there is a clear divide between performer and audience member), although behavioral norms vary across genres. Attendees at a Christian rock concert might get involved with worship, while hip-hop fans might dance, country fans might sing along, and audience members at an orchestral concert might sit in quiet contemplation or follow along with the printed score (a book of music that contains all of the orchestral parts). For the most part, concerts are intended to entertain ticket holders and to turn a profit for the artists and producers who present them.

In this chapter, we will examine four specific concerts that were staged in Europe and the United States between 1808 and 1969. We will consider the purpose for each concert, learn about the composers and producers involved in its presentation, and listen closely to a single musical work or performance. Each of these concerts was unique, and they span the gamut in terms of venue, audience, and repertoire. In order to set the stage for our encounter with concert culture, however, a brief overview of music as public entertainment is in order.

Despite the ubiquity of concerts today, musical performance as a major commercial venture has a relatively short history. In Europe, professional music first thrived in courts and churches. The wealthy staged elaborate musical presentations—such as the opera Orpheus (1607) at the court in Mantua, discussed in Chapter 4—for their own private consumption, but tickets were not put on sale. The Catholic church employed professional singers—such as Giovanni da Palestrina (1525-1594) at the Sistine chapel, discussed in Chapter 11—to provide music for worship services, but the music they produced was not intended to have entertainment value.

The first musical presentations for which members of the public could buy tickets were operas, which became available when the St. Cassiano Theater opened in Venice in 1637. Opera quickly became big business. Large crowds flocked to theaters to see the glamorous singers, fabulous costumes, and astonishing stage sets. However, there was one problem: In most places, the church authorities prohibited the performance of opera during the season of Lent. Lent, which constitutes the forty days preceding Easter, is the most solemn period in the church calendar. Members of most European Christian communities—most importantly, Catholics—were expected to abstain from frivolity and pass their time in spiritual contemplation. Opera was simply too exciting and fun.

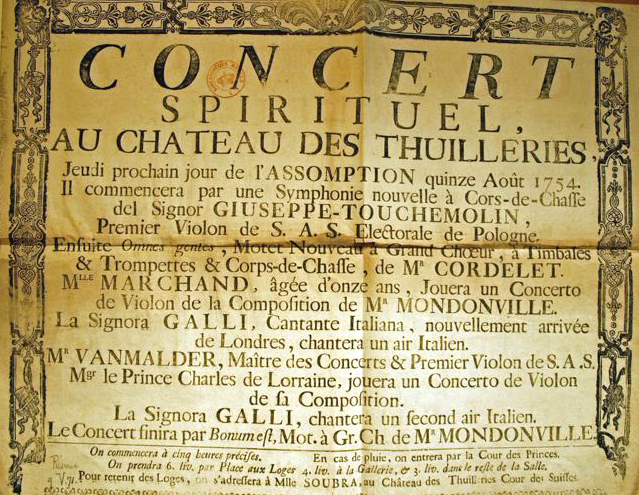

Concerts, therefore, were first introduced as a solemn alternative to opera. The most successful early concert series was launched in Paris in 1725. It was titled the Concert Spirituel, and—as the name suggests—offered uplifting entertainment that would not offend the Catholic Church. These early concerts included a great deal of variety. In addition to choral works with a sacred message, the program was likely to include concertos, arias, and improvisations. Most of the music would have been recently composed and, despite the advertising, was not explicitly sacred. In order to replicate the thrills of opera as closely as possible, each concert began the same way as an operatic performance: The first thing on the program was always a sinfonia for orchestra in three parts, or movements, ordered fast-slow-fast. Over time, this became the symphony, perhaps the most important genre of composition for orchestra.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, concerts became more and more important in European life. At the same time, orchestral music grew in prominence, and came to be understood as being more dignified and serious than opera. The idea of a concert as commercial entertainment, however, was never confined to the orchestra. In the 1830s, for example, the Hungarian pianist Franz Liszt began to give solo piano recitals across Europe (his career and music are discussed in Chapter 9). In the last 150 years, the concert model has been increasingly adopted by traditions outside of Europe. The first Chinese orchestra, the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra, was formed in 1879, while Indian classical musicians, who had formerly been employed by courts, began to stage public concerts near the turn of the century. These developments reflected a growing reliance on capitalistic economic models throughout the world, as musicians began to rely on ticket sales rather than aristocratic patronage.

The modern concert economy works in tandem with the recording industry, which has helped performing artists to gain international fame since the early 20th century. When you choose to buy tickets to a concert, it is usually because you already know and enjoy the music you are going to hear. This is a change from the earliest concerts, which were understood as an opportunity to introduce new music to the public. Such was the case with our first example.

1808: A Concert by Ludwig Van Beethoven

The Composer

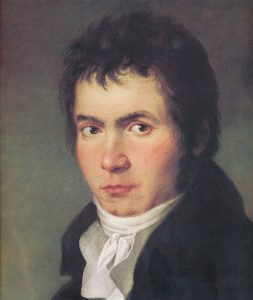

In 1808, the German composer and pianist Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was at the height of his career. He was living and working in the city of Vienna, which at the time was emerging as the musical capital of Europe. He had moved there in 1792 at the age of 21 to study with the famous composer Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809). Unfortunately, Haydn had just departed to present a concert series in London, so the two composers ended up having very little contact. By the time Haydn returned, Beethoven was already well established as a virtuoso pianist and composer of piano music.

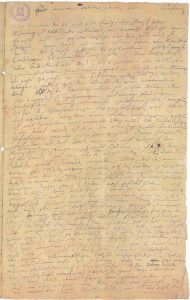

In 1798, however, an unforeseen health concern threatened to end Beethoven’s career: He began to go deaf. While loss of hearing would be a hardship for anyone, for Beethoven it was catastrophic. As a pianist, he relied on his hearing to play with orchestras. And as a musician, hearing was the sense that he valued most. Growing deafness took its toll not only on Beethoven’s professional life but on his social life as well, and he began to avoid gatherings of people out of fear that his disability would be detected. In an 1802 letter to his brothers, Carl and Johann, Beethoven wrote about the shame he felt related to his hearing loss: “How could I possibly admit such an infirmity in the one sense which should have been more perfect in me than in others, a sense which I once possessed in highest perfection, a perfection such as few surely in my profession enjoy or have enjoyed – O I cannot do it.”

This letter is known today as the Heiligenstadt Testament, due to the fact that it was written while Beethoven lived in the town of Heiligenstadt and was meant to serve as a last will and testament. It contains a great deal of insight into the composer’s state of mind during these difficult years, including the fact that he considered ending his life out of despair at his deafness. However, as Beethoven wrote, “only art it was that withheld me,” for “it seemed impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt called upon me to produce.” It would seem that his intense need to compose music compelled him to carry on, in spite of his enormous loss.

The Heiligenstadt Testament remained unknown until it was found among Beethoven’s papers following his death, for he never dispatched it to his brothers. However, it has since played an important role in cementing the public perception of Beethoven as an archetypical Romantic artist who became great through personal suffering. Before the 19th century, composers were seen as craftspeople. They created a product that was useful in everyday life, but they were not held in particularly high regard. Haydn, for example, although considered a great composer today, held the status of a servant for most of his lifetime (see Chapter 8).

In the early 19th century, however, things changed. The European public began to perceive prominent composers as “geniuses,” and they treated them with heightened respect. Where Haydn had been a servant, Beethoven was invited to dine with wealthy aristocrats and treated as their equal, or even superior. This change was brought about by economic and social transformations. A growing middle class meant that more people had the leisure time and financial means to consume art music, while a new set of Romantic values prioritized individual emotional expression. The public became particularly interested in portrayals of heartbreak, illness, and personal struggle—the same experiences that were understood to inform great artistic expression.

Beethoven suited the new requirements to a tee. He not only suffered deafness, but also endured repeated rejection from women (he never married) and a tempestuous family life. One of his tragic love affairs was captured in another letter, written in 1812 and addressed to a lady identified only as the “Immortal Beloved.” A few years later he lost his brother Karl to tuberculosis, despite his efforts to provide the best medical treatment. Following Karl’s death, Beethoven embarked on a bitter court battle to win custody of his brother’s son. After many years he prevailed, but the pressure he put on the child to follow in his own footsteps was so great that the boy attempted suicide. This is not the only example of Beethoven’s bad behavior. He was generally rude and inconsiderate of others, and was frequently evicted from his various lodgings for noise violations. He also practiced poor hygiene and frequently appeared disheveled in public. All of this, however, was not only forgiven but praised. Beethoven’s antisocial behavior contributed to his reputation as a genius.

Scholars have long described Beethoven’s career and output in terms of three periods: an early period, during which he primarily composed for the piano; a middle period, during which he focused on triumphant, large-scale works for public performance; and a late period, during which he became very experimental (indeed, some critics theorized that he had lost his mind). The 1808 concert that we about to explore marks the climax of Beethoven’s middle period. At this time, his struggle with hearing loss was known to the public, and he had become famous across Europe for his dramatic and ambitious symphonic works.

The Concert

Beethoven’s most famous concert took place on December 22, 1808, at the Theater an der Wien (Theater on the Banks of the Vienna River). For Beethoven, this concert was an invaluable opportunity to make some money and to premiere some of his recent compositions. However, circumstances in Vienna at the time made putting on a concert very difficult, and Beethoven faced a number of challenges in staging this event, which in the end was not particularly successful.

To begin with, competition from opera meant that a concert could only succeed if the opera houses were closed. That explains the date of this concert, which Beethoven scheduled to take place during the Catholic season of Advent (the four weeks leading up to Christmas). Unfortunately, the timing also had two undesirable consequences. Because there was a rush to present concerts during Advent, Beethoven found himself in competition with a much more prominent event taking place on the same night, and as a result he was not able to hire the top Viennese musicians. (Others simply refused to work with him due to his corrosive personality.) Another challenge came with the weather, for the hall was freezing cold on the night of the performance.

Even during Advent, it was difficult to put together a public concert. To begin with, there were no permanent orchestras in Vienna, so the concert organizer would have to recruit each individual musician, organize the rehearsal schedule, and arrange for payment. Booking a hall was also difficult. Beethoven was only able to do so because he happened to have a personal relationship with the director of the Theater an der Wien, for whom he had done various favors over the course of the year. Finally, putting on a concert required special permits from the government, which exercised tight control over public gatherings.

Under these adverse circumstances, it comes as no surprise that the December 22 concert did not go off without a hitch. Beethoven had to settle for second-rate performers, including an inexperienced soprano who struggled to overcome her nerves. However, most of the difficulties were of his own doing. To begin with, the concert was four hours long, which even in 1808 was considered trying. Beethoven saw the concert as an opportunity to share as many of his new works with the public as possible, so he did not restrain himself in assembling the program. In fact, Beethoven completed the final piece on the program only a few days before the concert, which created a further problem: His orchestra did not have time to learn it properly, and the performance fell apart so badly that Beethoven (who also served as conductor) had to stop and restart the work.

In keeping with the common practice of the time, Beethoven brought together works from a variety of genres for his concert. He also met expectations by starting with a symphony and including sacred vocal music. The most unusual aspect of his concert was that it featured music by only a single composer.

The evening began with his Symphony No. 6, also known as the “Pastoral” Symphony. This programmatic five-movement work portrays a visit to the countryside and takes about 40 minutes to perform. Next was Ah! Deceiver, the concert aria with which the young soprano struggled. This was followed by the Gloria from his Mass in C major and his Piano Concerto No. 4, with Beethoven as soloist.

The second half of the concert began with Symphony No. 5. After the Sanctus from the same Mass, Beethoven performed an improvised fantasy at the piano. Due to his progressing deafness, this was to be his last public performance as a pianist. The concert concluded with his new Choral Fantasy, an ambitious work for orchestra, choir, and vocal soloists.

The concert did not elicit positive reviews. In general, patrons thought that it was too long, too loud, and a bit overwhelming. As one of Beethoven’s supporters, the composer and critic J.F Reichardt, put it: “There we sat, in the most bitter cold, from half past six until half past ten, and confirmed for ourselves the maxim that one may easily have too much of a good thing, still more of a powerful one.”

Symphony No. 5

Despite its many shortcomings, Beethoven’s 1808 concert is remembered as one of the most remarkable of its era. December 22 marked both Beethoven’s last performance as a pianist and the premiere of many influential works. Symphony No. 6 later inspired Berlioz when he wrote his own programmatic symphony, the Fantastical Symphony (discussed in Chapter 6). The Choral Fantasy foreshadowed Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, which transformed the genre with the addition of choir and vocal soloists. And Symphony No. 5, which we will examine in some detail, has become perhaps Beethoven’s most famous composition.

Symphonies developed along with concert life. Due to their role as concert openers (and sometimes closers), 18th-century symphonies were usually lively and cheerful. They were almost always in the major mode. They were also fairly short, and composers tended to write a lot of them (Haydn composed 106). By the end of the 18th century, symphonies had four movements: a brisk opening movement, a slow second movement, a third movement inspired by dance, and an exciting finale.

While Symphony No. 5 is in many respects typical of the genre, it has a number of remarkable characteristics. Like other symphonies, it has four movements as outlined above. Unusually, however, these movements are linked by a single musical motif that is introduced at the beginning of the work: an ominous fournote pattern that was described by Beethoven’s first biographer as fate knocking at the door. This “fate motif” returns throughout the first movement and then in the subsequent movements as well—an unusual characteristic, since the movements of a symphony were usually kept independent from one another.

The technique by which a composer develops a large-scale work out of a single musical motif is known as organicism. While Beethoven was not the first composer to work in this way, he took the technique further than any had before him. Organicism was highly regarded in the Romantic era, when listeners wanted art to mirror nature. Just as a tree might grow from a tiny seed, Beethoven’s symphony grows from the opening “fate motif.”

Symphony No. 5 is also notable for its drama and serious tone. Beethoven was responsible for elevating the symphonic genre, transforming symphonies from entertainment into the loftiest artistic expression. This is evidenced by his output: Beethoven wrote only nine symphonies, but each took years to complete and set new standards for length and complexity. Symphony No. 5 is in the key of C minor, which sets it apart from the cheerful curtain raisers of earlier composers, and the opening “fate motif” makes it clear that this is not just light entertainment. From the start, listeners felt as if the symphony was trying to communicate something. It seemed rife with conflict and action. To understand what it might communicate, however, we will have to look at the music.

Sonata Form

The first movement, like that of all symphonies (and most other instrumental works) of the time, is in what is known as sonata form. Sonata form developed gradually during the course of the 18th century. Nobody invented it: Instead, a variety of composers experimented with formal design until a consensus emerged. By the 19th century, the components of the form were firmly in place, and listeners knew what to expect from a first movement. This gave the composer a lot of power, for Beethoven was able to tell a story by satisfying or frustrating the expectations of the audience.

A movement in sonata form has at least three parts: an Exposition (heard twice), in which contrasting themes are introduced; a Development, in which those themes are explored and transformed; and a Recapitulation, in which the themes from the Exposition are heard for a second time. The form also includes two optional parts. Some sonata-form movements open with an introduction, which is usually slow and stately. And many sonata-form movements conclude with a Coda, in which anything can happen. (The term “coda” is derived from the Latin word for “tail.”) Key areas are very important in sonata form. The Exposition starts with a Primary Theme in the home key, but moves to a different key for a Secondary Theme and Closing Theme. The Recapitulation, on the other hand, is entirely in the home key. The Development can move through a variety of key areas.

Minor-mode sonata form movements—such as the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5—are particularly interesting, because the composer has options for the key of the Secondary Theme. While the Primary Theme in the Exposition must be in minor, the Secondary Theme can be in minor or major. In other words, the Secondary Theme can have a sad/serious character or it can be cheerful/relaxing. If the Secondary Theme is presented in major in the Exposition, it can also be major in the Recapitulation—but the listener can’t be sure until they hear it!

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| Exposition | ||

| 0’00” | Primary Theme | The first thing we hear is the four-note “fate” motif, which will return throughout the movements. |

| 0’43” | Secondary Theme | This major-mode theme starts with the same motif, but its character is at first calm and restful. |

| 1’05” | Closing Theme | This theme is jubilant—it seems to have recovered from the angst of the Primary Theme. |

| 1’23” | Repetition of Exposition | We hear all of the preceding music for a second time. |

| Development | ||

| 2’45” | This section is dominated by the four-note “fate” motif, which we hear countless times. | |

| Recapitulation | ||

| 4’01” | Primary Theme | The Recapitulation opens with the “fate” motif, which comes crashing back in the full orchestra. |

| 4’17” | The Primary Theme is mostly identical to that heard in the Exposition, with the exception of this dramatic oboe solo. | |

| 4’49” | Secondary Theme | This theme is still in the major mode, suggesting that the movement might have a happy ending. |

| 5’15” | Closing Theme | This theme is also in the major mode, suggesting that the movement will conclude in major. |

| Coda | ||

| 5’31” | The Coda turns almost immediately to minor; like the Development, it is dominated by the “fate” motif. | |

| 6’01” | This entirely new theme suggests labor and struggle. | |

| 6’33” | The movement ends almost exactly as it began. | |

Beethoven used all of the sonata form tricks in the first movement of Symphony No. 5. The Primary Theme is stormy and anxious, not only because it is in C minor. The initial sounding of the fate motif by unison strings is obviously threatening, while the quick tempo and violent changes in dynamic that follow do nothing to calm the mood. The Secondary Theme, however, is in E-flat major, and it offers a moment of peace. Perhaps there is a chance to escape the storm.

In the Development, Beethoven was free to use any of the themes from the Exposition. However, he only explores the fate motif, which is heard dozens of times in all ranges and at all dynamic levels. Finally, he uses the fate motif to crash back into the Recapitulation. Following the Primary Theme, however, this is a plaintive, unmetered oboe solo that was not heard in the Exposition. This comes as a startling surprise, for the Recapitulation should not include any new musical material. What does it mean? Beethoven’s audience must have wondered. The Secondary Theme, which could return in major or minor, is in C major, and the Recapitulation concludes in C major. This seems to suggest a “happy ending” for the movement.

However, Beethoven is not finished. A massive Coda—which listeners would not necessarily have expected—immediately returns us to C minor. A new, pounding theme is introduced. After about a minute, we hear the fate motif one last time, followed by the first measures of the Primary Theme and a final cadence. The happy ending has escaped us, and we find ourselves back in the terrifying sonic world of the opening measures.

The story told by the first movement of Symphony No. 5 is certainly not a happy one. Despite moments of respite (the Secondary Theme), the listener is haunted throughout by the fate motif, and the devastating conclusion to the Coda reveals that we have not escaped it. Indeed, we are left right where we started. However, the symphony as a whole tells a more uplifting story. The second movement—a theme and variations—is calm and beautiful. It offers repose after the stormy opening. The third movement uses the fate motif as the basis for an aggressive march. The movement concludes, however, with a mysterious passage that ultimately transitions triumphantly into the fourth movement, which is in a resounding C major.

Movement IV

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| Exposition | ||

| 0’00” | Primary Theme | This theme opens with a triumphant statement in the brass that ascends through the pitches of a major triad before returning to the tonic; next, the violins repeatedly play an ascending major scale. |

| 0’30” | Transition Theme | Although transition themes are not always memorable, this one features a powerful motif in the low brass. |

| 0’53” | Secondary Theme | This theme is more relaxed than the Primary Theme; it has a dance-like lilt. |

| 1’17” | Closing Theme | The energy builds again with this theme. |

| Development | ||

| 3’27” | This section is dominated by the Secondary Theme. | |

| 4’51” | This passage quotes Movement III; in it, we hear the short-short-short-long rhythmic motif that dominated Movement I. | |

| Recapitulation | ||

| 5’20” | Primary Theme | This presentation is nearly identical to that in the Exposition. |

| 5’50” | Transition Theme | This presentation is similar to that in the Exposition, but it does not change key. |

| 6’16” | Secondary Theme | This presentation is nearly identical to that in the Exposition. |

| 6’40” | Closing Theme | This presentation is similar to that in the Exposition, but it is extended and builds into the Coda. |

| Coda | ||

| 7’06” | The Coda begins with material from the Secondary Theme. | |

| 7’33” | This passage contains new thematic material. | |

| 8’12” | At this point, the tempo greatly accelerates. | |

| 8’35” | We hear a fast-paced version of the motif that opened the movement; the Coda ends with a series of accented chords. | |

To see how the story ends, we will take a close look at the fourth movement, which opens with a brilliant trumpet fanfare. The Exposition maintains a sense of joy and excitement throughout, but the Development introduces conflict as sections of the orchestra wrestle the themes through minor keys. The Development concludes with a repetition of the minor-mode march theme from the third movement. This was highly unusual for the time, and must have shocked Beethoven’s audience. Once a movement was over, they didn’t expect to hear its themes again. The march theme, which is presented in a quiet pizzicato by the strings, introduces a sense of uncertainty and discomfort, but it once again transitions into a triumphant Recapitulation. This time, the Coda—which accelerates to a breakneck tempo— provides the joyful ending that we were denied in the first movement.

Listeners in 1808 did not just hear Symphony No. 5 as a piece of music for orchestra. They heard it as an autobiographical account of Beethoven’s personal struggle with hearing loss. The opening motif represented his own tragic fate, and the first movement expressed his suffering. The final movement, however, portrayed his victory over fate. He had struggled with his disability and had emerged triumphant. This narrative trajectory from darkness to light would later be imitated by other composers, including Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Symphony No. 4) and Dmitri Shostakovich (Symphony No. 5, discussed in Chapter 10), each of whom also sought to tell a musical story about overcoming adversity.

1933: A Century of Progress

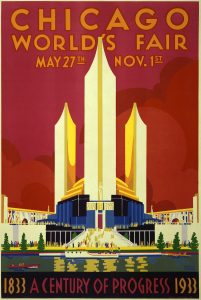

In 1933 race became the focal point of another important concert. The object was to celebrate the accomplishments of African American composers and performers in the overwhelmingly white world of European-inspired orchestral music. The concert in question took place as part of the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair, titled “A Century of Progress,” and it is remembered for the first performance of a symphony composed by an African American woman, Florence Beatrice Price.

The Composer

Florence Price (1887-1953) was born to upper-class parents in Little Rock, Arkansas. At the time, the population of Little Rock was one-third African American and the city had a thriving and self-sufficient black community. Her father was the city’s only black dentist, while her mother was a successful real estate investor. Both of Price’s parents had been born free, and both had enjoyed the advantages of a good education. As such, they considered themselves responsible for furthering the uplift of the black community in Little Rock by promoting education and the arts.

In 1903, Price left Little Rock to study music at the New England Conservatory, where she quickly rose to the top of her class. She was invited to study with the most exclusive composition teacher, and graduated in just three years with diplomas in piano teaching and organ performance. Upon completing her education, she returned home to carry on the uplift mission of her parents. She taught music at black colleges near Little Rock until 1910, when her father died. After a further two years teaching at Clark University in Atlanta, Price returned to Little Rock to marry the city’s leading black lawyer. In keeping with social expectations, she gave up her college teaching career to raise children, but she also took the opportunity to return to composition.

The Prices settled in Little Rock, despite the fact that life was becoming increasingly difficult for the black community there. Jim Crow laws instituted in the 1890s had greatly reduced the opportunities for African Americans, and lynching became increasingly common. In 1927, the Prices determined that they could no longer tolerate the oppressive social climate and moved to Chicago, joining the wave of black Americans who left the South during the Jim Crow era.

In Chicago, Price quickly became involved with various organizations concerned with the advancement of African Americans and women in music. These included the Chicago Music Association (the local branch of the National Association of Negro Musicians) and the Chicago Club of Women Organists, of which she was the first black member. As her husband’s career floundered, Price became the primary breadwinner. In addition to her serious concert music, Price composed popular songs, church music, and educational pieces for piano students, and during the Great Depression she took a job as a theater organist, accompanying silent films. Her husband did not adapt to his change in fortunes well, and soon became abusive. Price secured a divorce and custody of their two children in 1931.

Despite financial and personal struggles, the 1930s would see Price emerge as a composer of national significance. In addition to Symphony No. 1, Price composed other large-scale symphonic works, including her Piano Concerto in One Movement (1934) and her Symphony No. 3 (1938-40), both of which were premiered by major orchestras and praised by critics. In 1935 she returned in triumph to Little Rock, where she gave a concert of her piano music to benefit the underfunded black high school from which she had graduated. And in 1939, the renowned soprano Marian Anderson closed another famous concert, given from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, with Price’s arrangement of the African American spiritual “My Soul’s been Anchored in de Lord.” (Anderson sang at the Lincoln Memorial after the Daughters of the Revolution refused her permission to rent Constitution Hall on the basis of her race.) Anderson became a great admirer of Price and sang many of her songs, thereby further raising Price’s visibility at the national level.

All the same, Price never broke into the very highest echelons of American concert life—those guarded by the elite institutions of New England. For a full decade, she wrote regular letters to the director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, asking that he consider programming her music. In the most famous of these, written in 1943, she opened by directly addressing the two nearly insurmountable challenges that had impeded her career throughout her life: “To begin with I have two handicaps—those of sex and race. I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins.” Price went on to clarify that she was not expecting special consideration, but asked only that her work be judged on its own merits. Despite her efforts, however, Price’s orchestral music was not heard on the East Coast in her lifetime.

The Concert

In 1932, Frederick Stock, conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, was appointed music advisor for the upcoming Chicago World’s Fair, “A Century of Progress.” Stock had already made a name for himself as a champion of American music. Although the American concert establishment of the early 20th century was dominated by German-speaking emigres (Stock himself was born in Prussia), Stock broke new ground in 1917 by committing to include music by at least one American composer in each of his concerts. He was often ridiculed for doing so, as many critics still believed that European music was inherently superior. Stock doubled down with his vision for the World’s Fair, however, promising to showcase “Chicago talent first and American talent second” while keeping European representation “drastically limited.”

Stock became aware of Price that same year after her Symphony No. 1 took first prize in the orchestral division of the Rodman Wanamaker Competition, which since 1927 had offered recognition to the best African American composers. Price also earned an honorable mention in the same division and won prizes with two of her piano pieces, while the song prize was secured by her friend and student Margaret Bonds. In the end, these two Chicago women walked away with all of the top honors.

Stock immediately approached Price about premiering her Symphony No. 1 in connection with “A Century of Progress.” He imagined it as part of a program celebrating the accomplishments of black composers and performers, with an emphasis on those with ties to Chicago. It seems that Stock was also interested in emphasizing the legacy of African American music, for he specifically programmed works that drew from black traditions such as jazz and spirituals.

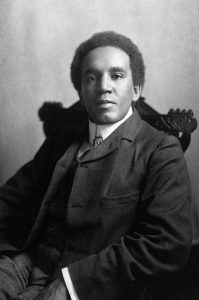

Before we examine Price’s symphony, we must address the other components of the program. We will begin with the composers. Perhaps the best known in 1933 was Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912), an English composer of mixed race. Coleridge-Taylor had visited the United States several times and was interested in the use of African American folk music in concert works. The program included an aria from his cantata Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast—a decidedly American topic—and Bamboula, a piece inspired by African dance rhythms.

The other featured composer was John Alden Carpenter (1876-1951), whose jazz-influenced Concertino for Piano and Orchestra occupied the central position in the program. Carpenter was a white composer, but Stock clearly considered his work to display black musical influence. He was also a Chicago resident. Carpenter’s Concertino was in the tradition of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, which had been performed the night before as part of an American program. In fact, Carpenter even brought Gershwin with him to the premiere!

The piano soloist was none other than Margaret Bonds, who had recently won composition prizes alongside Price. Performing Carpenter’s Concertino was not Bonds’s only contribution to the concert, however. She also spent many long nights helping Price to copy out the parts to her symphony. Price had a particularly busy year, and was not able to abandon her work as a pianist, lecturer, choir director, and radio arranger in order to focus on the premiere of Symphony No. 1. As a result, many members of the black musical community rallied to her aid.

At the top of the bill was Roland Hayes, a well-known tenor who would later become the first African American to record music from the European concert tradition. Hayes sung one such piece on the Chicago concert: an aria by the French composer Hector Berlioz. By doing so, he demonstrated that he was the artistic equal to any white singer. His other selections, however, were all linked with black culture. Near the end of the program, Hayes sang two spirituals, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Bye and Bye.” The first had been arranged by the great African American singer and composer Henry T. Burleigh, while the second was Hayes’s own arrangement. He also sang the Coleridge-Taylor aria.

There was one other piece on the program: John Powell’s concert overture In Old Virginia. Powell (1882-1963) was another white composer, although he was known for incorporating Southern folk melodies—often of African American origin—into his music. Powell was also an outspoken white supremacist and advocate of eugenics. As an active contributor to Virginian political life, he helped to imagine and author the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which set out to define and separate the “white” and “colored” races. According to the Act, even a single drop of non-white blood in an individual’s ancestry qualified that person as “colored,” meaning that they were subject to Jim Crow segregation and could not enter into marriage with a “white” person. This is but one item among many in Powell’s antiblack legacy, and his inclusion on the “Century of Progress” emphasizes the great deal of progress that was still left to be made.

Price’s symphony was well-received by both the public and the critics. Wearing an elegant, floor-length white gown, she was repeatedly called to the stage by a rapturous audience to take bows following the premiere. The black press generally praised her symphony as a great achievement on behalf of the African American community. Writing for the Chicago Defender, a black newspaper, Robert Abbott described what the premiere meant to his readers: “First there was a feeling of awe as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, an aggregation of master musicians of the white race, and directed by Frederick Stock, internationally known conductor, swung in to the beautiful, harmonious strains of a composition by a Race woman.” White critics tended to praise the music as a fine contribution to the European concert tradition. Eugene Stinson of the Chicago Daily News, for example, described Symphony No. 1 as a “faultless work” that “is worthy of a place in the repertory.”

Symphony No. 1

Florence Price belonged to the cultural movement now known as the Harlem Renaissance, and much of her music exemplified its values. The Harlem Renaissance was driven by African American artists and intellectuals living and working in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan, although its influence spread across the nation. These cultural leaders took pride in their ancestry and encouraged the celebration of black heritage in literary and artistic works. By contributing to and elevating a rich tradition of African American culture, they hoped to improve life for the entire black community.

Symphony No. 1 provides a characteristic example of Price’s engagement with her musical heritage. It was not her tendency to directly quote African American music in her compositions. However, she was deeply influenced by the tonal, rhythmic, and textural characteristics of such music, and she wove these elements into traditional European forms to create sophisticated concert works from a uniquely black perspective.

Because she was working in the European tradition, the overall form of Price’s symphony is the same at Beethoven’s. It begins with a long movement in sonata form. Next is a slow movement, followed by a dance movement, while the finale is fast-paced and exciting. We looked at the first and last movements of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, so we will examine the two internal movements of Price’s Symphony No. 1.

Movement II

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | A | This hymn-like theme is played in the brass and accompanied by an African drum; clarinets and flutes echo each phrase in a call-and-response texture. |

| 1’57” | B | The strings play a mournful, descending theme that outlines a pentatonic scale and includes bluesy elements, including a slide and unusual harmonies. |

| 3’37” | A | |

| 4’52” | Development | A phrase of the A theme leads into an extended development-like passage in which the A and B themes are explored and transformed. |

| 6’48” | The B theme returns, first in the oboe. | |

| 9’31” | A’ | This time, an active clarinet line accompanies the hymn-like theme, the phrases of which are interspersed with bells. |

| 11’22” | Coda | The entire orchestra plays the A theme; clarinet and cello solos lead into the final chord. |

The second movement begins with a theme that sounds like it might be a hymn. Several characteristics of the music combine to create this impression. To begin with, the melody is slow and stately. It is played on brass instruments, which have a long association with the church. Finally, the texture is that of a Christian hymn. The melody is clearly in the top voice, but all of the voices move in coordination, executing the same rhythmic patterns. This is called homophonic texture. Despite all of these clear indicators, however, what we are hearing is not a real hymn, but rather a hymn-like theme composed by Price.

Price had several good reasons to base her slow movement on such a theme. There was a long tradition of including hymn themes in symphonies, especially among composers who wished to demonstrate national pride. Ever since the early 19th century, music of the Christian church has been used to signify national identity by European composers. In addition, Price herself was deeply committed to her religious beliefs and would have been inclined to express herself in the musical language of the church. Finally, her orchestration in this movement reveals the influence of the church organ—an instrument that Price performed on and wrote for.

Price’s hymn theme has several characteristics that betray African American influence. The first is the irregular length of its opening two phrases, each of which is five measures long. Similar phrasing can be found in African American spirituals, which seem to have provided Price with a model. Each of these phrases is followed by a short echo from the winds—an example of the call-and-response technique prevalent in black music. Finally, the hymn is accompanied by an African drum, one of several instruments that Price added to the standard orchestral percussion section. Another is the orchestral bells, which are heard later in the movement.

To complement the hymn theme, Price introduces a contrasting second theme in the violins, which play a descending melody that outlines a pentatonic scale. A pentatonic scale is a five-pitch subset of a major or minor scale; this one includes scale degrees 1 3 4 5 and 7 of a minor scale. Pentatonic scales are typical of indigenous music traditions found around the world, so the missing scale degrees give this theme a folk-like feel. At the same time, bluesy elements identify its character as uniquely African American. A descending slide is reminiscent of blues guitar playing. This is followed immediately by some blues-inspired harmonies, which include extended chords not often heard in European-style concert music and clashes between minor-mode melody and major-mode accompaniment.

The hymn theme returns, but this time it transitions into a lengthy development-like passage that explores the movement’s two themes. First we hear the hymn motif move throughout the orchestra, acquiring various characters and expressions on its journey. Then the second theme returns in the oboe, although a re-harmonization means that it does not sound nearly as mournful. The movement concludes with a dignified return of the hymn theme, which resolves into a peaceful and satisfying final chord.

Movement III

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | Rondo theme A | The violins play a syncopated pentatonic melody accompanied by minor-mode harmonies. |

| 0’18” | Rondo theme B | The trumpets play a contrasting major-mode melody. |

| 0’35” | C | The violins play a minor-mode melody accompanied by slide whistle |

| 0’53” | Rondo theme A | The A theme returns in the winds, now with major-mode harmonies. |

| 1’01” | Rondo themes A & B | The trumpets enter with the B theme while the cellos continue to play the A theme. |

| 1’10” | Rondo theme B | The whole orchestra plays the B theme. |

| 1’27” | D | A new melody is heard in the horns. |

| 1’51” | The violins enter with a fragment of the B theme before picking up the D theme. | |

| 2’08” | Rondo theme A | The whole orchestra plays the A theme, which is accompanied by major-mode harmonies. |

| 2’25” | Rondo theme B | The whole orchestra plays the B theme. |

| 2’40” | Coda | A surprising harmony begins the transition into a final triumphant statement of the B theme; the tempo decreases leading into the final cadence, which is underscored by rolls on the snare drum. |

The third movement is more explicitly African American in character. Price titled it “Juba Dance,” in reference to a traditional dance performed by enslaved people that had roots in African culture. The specific steps of the Juba varied, but it usually contained elements of hand clapping, foot stomping, and body percussion (such as thigh slapping) that became known as “patting juba.” Body percussion played an important role in 19th-century African American music, for it facilitated dancing even in the absence of other instruments. It also replaced traditional percussion instruments, which were outlawed in most of the South; slave holders feared that enslaved people might use drums to communicate between plantations for the purpose of coordinating revolts.

Although other composers had previously used Juba rhythms in their music, Price was the first composer to incorporate Juba influence into a symphony. She considered the rhythmic element in African American music to be of “preeminent importance.” The third movement of Symphony No. 1 opens with a syncopated pentatonic melody in the violins, heard over a steady rhythmic pattern in the lower strings and percussion (we hear African drums again in this movement). The choice of violin for this melody calls to mind an enslaved fiddler, providing dance music on the plantation. The melody itself is intriguing, for it alternates between modes, first seeming to be in the minor mode but later resolving in the relative major. This characteristic is frequently encountered in folk music. Finally, “Juba Dance” requires yet another literal folk instrument: the wind whistle, which has roots in indigenous cultures.

“Juba Dance” is in rondo form, meaning that the opening pair of melodies return throughout. Each time, however, they undergo some sort of change. Different instruments perform the melodies, and they are accompanied by various countermelodies. In between, contrasting melodic material explores the diverse rhythmic possibilities of African American dance music.

1969: An Aquarian Exposition

Popular Music as Concert Art

All of the concerts we have examined so far have been relatively formal affairs. They have taken place in concert halls, and the audience members have been expected to sit quietly and give all of their attention to the music. This final aspect is the hallmark of concerts: They are primarily for listening—especially in the world of art music, wherein composers and performers generally expect to have the undivided attention of the audience.

There is a long history of concert presentation in popular music traditions as well. We will focus on those of the United States. In the mid-19th century, for example, the Hutchinson Family Singers became famous for their concerts of songs promoting abolition and women’s rights. Their music was aimed at an educated, middle-class audience; those who wanted more lively entertainment would attend theatrical productions. Although most concerts featured singers, one could also hear brass band concerts in local parks—or, by the end of the 19th century, even attend one of the lavish concerts put on by the showman John Philip Sousa (see Chapter 12).

For the most part, however, American popular music has historically been found outside of the concert hall. In the early 20th century, one expected to hear the latest hit songs not in concert but as part of musical theater productions, variety shows, and motion picture programs. Likewise, the music played by ragtime pianists and jazz bands was mostly heard in drinking establishments and dance halls. This is one of the reasons that Paul Whiteman’s An Experiment in Modern Music was such a noteworthy event: He expected his audience to sit and listen critically to music that had been consumed primarily in the context of social dancing. Whiteman also sought to blur the lines between popular and art music during a time when the two were considered to be fundamentally different.

Over the subsequent decades, however, this paradigm began to dissolve. Improvements in recording and broadcasting technology increased the flow of popular music into homes across the nation, and a powerful recording industry soon emerged. In the 1950s, a craze for rock ‘n’ roll swept the youth market. Television played an important role in building enthusiasm for the new musical style, but young people also wanted to see their favorite bands in person. At first, rock ‘n’ roll was primarily dance music. In the 1960s, however, the songs released by popular music labels became increasingly complex and sophisticated. (See, for example, the album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, addressed in Chapter 7.) This music—termed rock—was, like classical music, meant primarily for listening.

Rock concerts grew in size and frequency during the 1960s for several reasons. One was technological. A symphony orchestra can be made louder by adding more instruments; that’s how Hector Berlioz and Richard Wagner overwhelmed audiences in the 19th century. A rock band, however, gets louder by using amplification equipment that can produce sound at a higher wattage. The early 1960s saw significant developments in amplification technology that allowed bands to player louder than ever before. This in turn made it possible for rock bands to perform in larger venues, including stadiums and outdoor amphitheaters.

Americans also turned increasingly to popular music as they sought to understand and cope with the turbulent times in which they lived. The 1960s saw domestic upheaval on a level unprecedented since the Civil War of the 1860s. A series of high-profile political figures were assassinated, one after another: President John F. Kennedy in 1963, Malcolm X in 1965, and, in 1968, both Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. The Vietnam War provoked increasingly violent protests, which were to culminate in the Kent State massacre of 1970. The Stonewall riots of 1969 marked the start of the LGBTQ rights movement, while the decade also brought the women’s liberation movement to the forefront of America’s conscious. The civil rights movement saw victories, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but black Americans continued to face discrimination and hate.

The “classical” music establishment of the 1960s was not well equipped to provide solace or emotional relief to listeners. After World War II, most serious composers abandoned audience-friendly styles in favor of experimental music. They did so for a variety of reasons: the fear that beautiful music could be turned to evil purposes (see, for example, Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana in Chapter 10), the conviction that human beings were inherently corrupt and should not use music to express their emotions at all, an intense desire to break completely with the past after the horrors of the war, and sheer fascination with the mathematical and acoustic potentialities of sound. Some composers continued to write beautiful and expressive music that helped listeners to grapple with feelings of loss and disillusionment: Benjamin Britten’s 1962 War Requiem is an excellent example. For the most part, however, listeners embraced popular performers whose music captured their hopes and frustrations.

As a result of all this, rock artists gained prestige and influence, and the rock concert became a mainstream cultural activity. Economically, 1960s rock concerts served the same purpose as Beethoven’s 1808 concert: They made money for the band and its agents while winning new fans and developing interest in the music. People also attended for the same reasons (love of music and affirmation of social status), even if they behaved a bit differently. Near the end of the 1960s, concert promoters began to see the possibility of turning even bigger profits by organizing not just concerts but music festivals—multi-day celebrations that would bring together popular bands and attract tens of thousands of patrons.

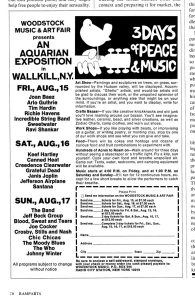

The first major music festival was the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival in Monterey, CA. This three-day event attracted 50,000 people and was immediately regarded as one of the great cultural landmarks of the decade. Its success inspired a slew of imitations. In 1968, the Newport Pop Festival and the Miami Pop Festival each attracted around 100,000 people, while the next year the Atlanta Pop Festival and the Atlantic City Pop Festival brought in closer to 110,000. However, all of these paled in comparison with the music festival that would go down in history as a watershed not only in the history of popular music but in the history of American culture: the 1969 Aquarian Exposition, better known as Woodstock.

The Festival

Woodstock began as a promotional idea for a new music recording business. Early in 1969, Michael Lang and Artie Kornfeld contacted New York City entrepreneurs Joel Rosenman and John P. Roberts for help financing a small recording studio in the town of Woodstock, NY. Rosenmann and Roberts were skeptical about the studio’s potential for success, but their attention was captured by a passage in the business plan that sketched out a small-scale music festival intended to celebrate the studio opening. They encouraged Lang and Kornfeld to abandon their idea for a studio and instead focus on putting together a festival to take place in Woodstock. The four young men agreed that the idea was good, and they founded a company, Woodstock Ventures, to facilitate the project.

Lang already had some experience with the business end of music festivals, having co-organized the Miami Pop Festival in 1968. The Miami Pop Festival was small, attracting about 25,000, but it prepared Lang to anticipate the many logistical concerns that the team would face. And the festival at Woodstock wasn’t supposed to be that much larger: The organizers hoped to attract 50,000 people at the most.

Things went wrong from the start. First, the organizers needed to find a location. It was important to them that the setting for the festival be attractive and bucolic, far away from the noise and pollution of the city. They wanted to sell the idea of an escape to nature, where participants could enjoy “3 days of peace & music.” Lang and Kornfeld initially planned to hold the festival in Wallkill, NY, but local residents balked at the idea of a hippie invasion and were able to prevent them from securing the site. Next, they tried to book a venue in Saugerties, NY, but again the deal fell through.

Rosenman and Roberts, growing impatient with the other pair’s failure to confirm a location, leased a 300-acre industrial park in Wallkill for the festival. The town’s residents, however, launched a fierce attack against the project, and in July the Town Board passed a law requiring a permit for gatherings of more than 5,000. Later in the month, the Wallkill Zoning Board of Appeals banned the concert altogether on the grounds of sanitation concerns.

Finally, Rosenman and Roberts were introduced to dairy farmer Max Yasgur, who agreed to lease his 600-acre farm outside of Bethel, NY. Again, however, the organizers were met with local resistance, and they were unable to secure building permits from the Town Board until August 2—less than two weeks before the advertised start of the festival.

This left the organizers in a very difficult situation, for they simply did not have time to erect all of the infrastructure that is necessary for a large outdoor festival. However, people were coming: The conflict between the festival organizers and the authorities in Wallkill had been widely reported, with the result that far more people knew about the festival than might have otherwise. About 186,000 advance tickets had already been sold, and the organizers had reason to believe that a far greater number of people were planning to attend.

The organizers decided to focus their resources on the most important piece of infrastructure, the stage—for what is a music festival, after all, without a stage for the performers. This meant that fencing (to keep out unticketed patrons) and ticket booths (to sell those tickets) were left unbuilt, and Woodstock became, practically speaking, a free festival. (Woodstock Ventures did eventually turn a profit, but most of this came from a documentary made at the festival and released in 1970.)

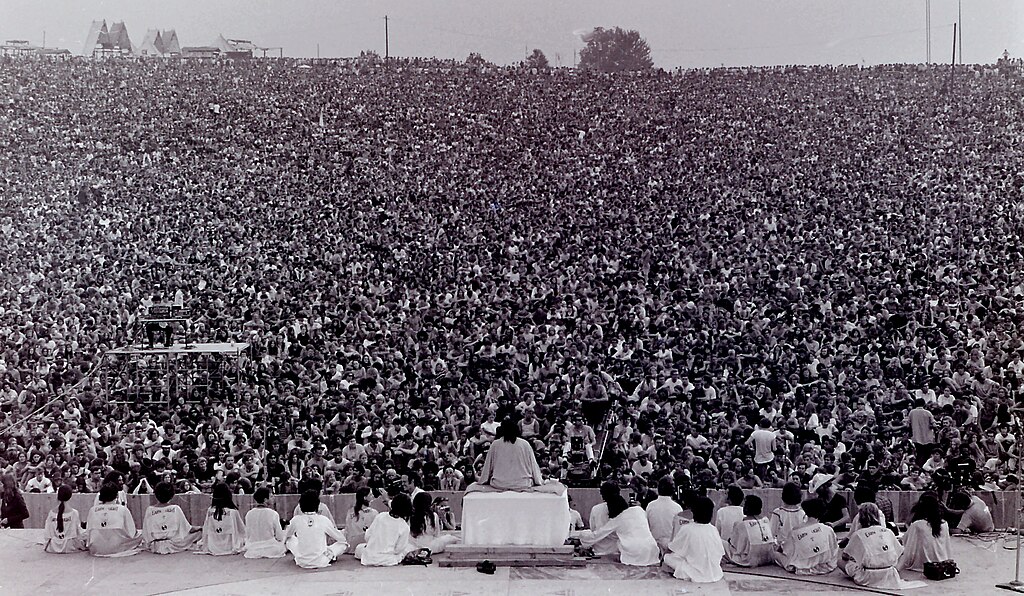

Although the organizers expected crowds, nobody could have imagined that people would flock to the festival in the numbers that they did. The morning of Friday, August 15, saw traffic jams that extended all the way back to New York City. Many people abandoned their cars and walked the final miles to the festival site, while the performers and sound crew had to be brought in by helicopter. Eventually, a state of emergency was declared in Sullivan County to deal with the unprecedented influx of people. The Governor of New York even threatened to call in the National Guard, but Roberts convinced him not to. All told, nearly 500,000 people attended the festival: ten times more than the organizers had anticipated.

It is on these half a million people that we will now focus. Why did they come? And why did so many of them come? It is certain that visitors to Woodstock made the pilgrimage for many different reasons. Some were attracted by the rural setting (previous festivals had mostly been in cities). Some were intrigued by rumors about the legal wranglings that had kept the festival out of Wallkill. Some were excited by the lineup of star performers. Whatever their individual reasons for attending, however, almost all of the visitors to Woodstock were seeking some kind of relief in the midst of growing social unrest. Many were disillusioned by President Richard Nixon’s foreign policy, which had so far failed to bring the violence in Vietnam to an end. Others still grieved for Kennedy and King, whose murders came as a devastating blow to the civil rights movement. Woodstock, however, was not about politics—it was about music and community.

Naturally enough, the festival organizers and local government officials were worried about what might happen when nearly 500,000 people came together on a mere 600 acres. Similar gatherings had been marred by violence, and festivals were likely to attract troublemakers. Astonishingly, there were no violent outbreaks of any kind. This is even more remarkable when one considers the fact that the festival’s troubles did not end with traffic. Because of the rush to construct the stage, other facilities were inadequate or non-existent. Camping was crowded, and few visitors were well-prepared. At first there was no food available on site at all; later, festivalgoers waited in line for hours to buy hot dogs.

In addition, it rained. Wind and rain on Sunday afternoon brought the festival to a halt for several hours. Stage hands rushed to cover expensive sound equipment, while audience members huddled under plastic sheets. The fields turned to mud. All of this could easily have led to discontent and rioting—but instead, the visitors peacefully waited out the storm until the musicians could return to the stage.

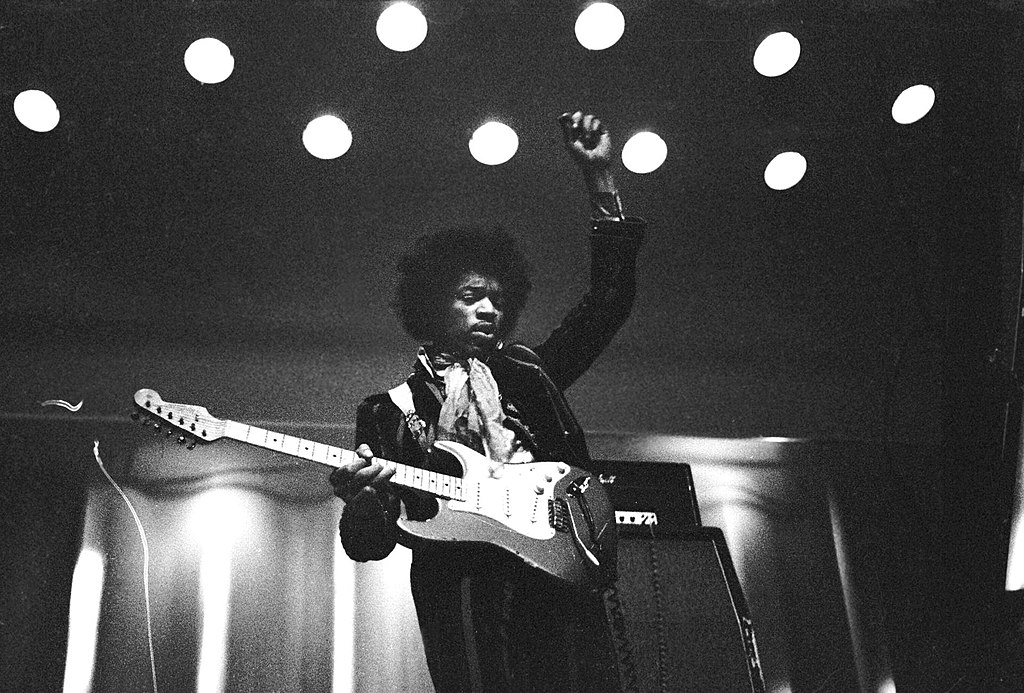

The Sunday storm also had a significant impact on Woodstock’s musical legacy. The festival headliner, Jimi Hendrix, was supposed to close out the program on Sunday night. Because of storm delays, however, he did not take to the stage until 9 am on Monday morning. His set is remembered as the highlight of the festival. In particular, his rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” has become an iconic cultural artifact representing not only Woodstock but the entire 1960s. However, by Monday morning, only about 30,000 people remained in the audience—everyone else had gone home.

We will consider Hendrix and his performance in detail, but first it is necessary to survey the musical program in general. The first band to sign a contract was Creedence Clearwater Revival, whose fame quickly attracted other major artists to the festival. Other big names included Santana, Janice Joplin, The Grateful Dead, The Who, Jefferson Airplane, Sly and the Family Stone, and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young. Also on the program was the North Indian musician Ravi Shankar (discussed in Chapter 6), who had also played for enthusiastic crowds at the Monterey Pop Festival.

Just as interesting is the list of musicians who did not appear at Woodstock—especially those who are discussed in this book. Bob Dylan actually lived in Woodstock, but had planned a trip overseas to perform at the Isle of Wight Festival. Simon and Garfunkel were working on a new album. And The Beatles had already given up live performance for good.

Jimi Hendrix’s Set: “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Purple Haze”

Jimi Hendrix (1942-1970) was the most accomplished and influential guitar player of the 1960s. He entranced audiences with his virtuosic feats and inspired a new generation of performers to treat their instruments as tools not only for the production of melodies and harmonies but for the sculpting of sound. His influence was particularly strong on Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, and Jimmy Page, all of whom responded to his unique ability to combine incredible musicianship with an innovative use of amplifier distortion and other effects to create sounds hitherto unheard. He experimented with a range of timbres that often crossed over into the world of pure noise, but which defined his playing and enlivened his studio albums—all five of which reached the Top 10 in the Billboard charts.

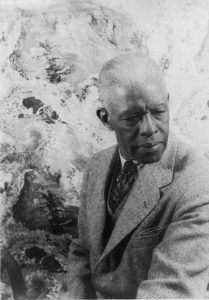

Hendrix was born in Seattle, WA, where he began playing the guitar at the age of 15. He was particularly influenced by Elvis Presley and blues musicians such as Muddy Waters, and he spent his spare time learning their tunes by ear. Hendrix had a difficult childhood. His father was serving in the US Army at the time of his birth. Following his discharge at the conclusion of World War II, the family struggled financially and both parents took to abusing alcohol, resulting in Hendrix’s mother’s death at the age of 33. Hendrix himself joined the Army after getting into trouble with the law as a teenager. He trained as a paratrooper, but his unprofessional behavior (he played guitar constantly, slept at his post, and failed to report for inspections) led to an honorable discharge on June 29, 1962, just over a year after he had enlisted.

Freed from his military obligations, Hendrix took to music as a full-time pursuit. He first moved to Clarksville and then to Nashville, TN, where he had access to a variety of performance opportunities. Hendrix found work playing with bands that toured the Chitlin’ Circuit, which was a collection of Southern and Midwestern music venues that were friendly to African American performers during the Jim Crow era.

All the same, Hendrix found his career opportunities limited by his race. In addition to the fact that he faced discrimination at performance venues, he also found that mainstream ideas about black musicians prevented him from playing the music he really loved. In Tennessee, Hendrix mostly played rhythm ‘n’ blues, the most prominent genre of popular music associated with the black community. However, he felt an affinity for rock music and considered himself to be a rock guitarist. It was therefore difficult for him to fit into the American music scene.

In 1966, Hendrix solved this problem by moving to London. There, he put together a rock trio with bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell. They called themselves the Jimi Hendrix Experience and immediately made a splash on stage and in the recording studio. We have already seen how 1960s music was dominated by British bands in what has been termed the British Invasion. In a way, Hendrix himself became a British Invasion artist. His fame in the UK allowed Hendrix to remake his image and return to the United States under his own terms.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience made their US debut at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, where Hendrix astonished music fans and performers alike with his ability as a guitarist (and his stage antics: he set his guitar on fire). He was therefore a natural choice for Woodstock, where he was paid the top fee of $18,000. Hendrix came to the festival with his new band, Gypsy Sun and Rainbows, although they were famously mis-introduced by the announcer as the Jimi Hendrix Experience. The band included several of Hendrix’s associates from Tennessee, including bassist Billy Cox and second guitarist Larry Lee. Additional percussion was provided by Juma Sultan and Gerardo “Jerry” Velez.

However, Hendrix almost didn’t go on stage. He was upset by media reports suggesting that the festival was in shambles, and discouraged by the number of attendees: Hendrix didn’t like playing for large crowds. As of Saturday afternoon, he was still refusing to perform, but his manager finally talked him into fulfilling his contract. It took the band hours to make their way to the festival by car, where they found that no dressing rooms had been constructed. The newly-formed band was also under-rehearsed. According to Sultan, “We did not have a plan, we didn’t know what he was gonna play.” Although the set was recorded, two of Hendrix’s numbers from Woodstock have never been released—his estate has declared that they do not meet the required performance standard and has persistently refused to allow publication.

Despite shortcomings, the two-hour performance has been described in transcendent terms by those who were there. Sultan provides the perspective of a band member: “It felt like three minutes, I walked out there, the sun was coming up and there was a sea of people, all this good energy, they were coming with the sun and light, it was overpowering. We could have played for hours more. . .” We will consider an eight-minute segment from near the end of Hendrix’s set containing “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Purple Haze.”

“The Star-Spangled Banner”

Hendrix’s performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner”9 has been remembered as the culmination of Woodstock—a seemingly improvised expression conjured in the moment to express the hopes and fears of the crowds that had gathered there. In reality, Hendrix’s “Star-Spangled Banner” was neither an improvisation—a rendition created in the act of performance—nor was it original to the festival. In fact, he had performed the national anthem more than thirty-five times in the month prior Woodstock, and would continue to include it in his concert appearances for the remainder of his career, making for a total of over sixty performances. What the audience heard was his carefully-considered arrangement of the national anthem for solo electric guitar.

“The Star-Spangled Banner”

Composer: John Stafford Smith/Francis Scott Key

Performance: Jimi Hendrix (1969)

Before we can address his arrangement, however, we need to consider the equipment that Hendrix used to create his sounds. At Woodstock, Hendrix played a white 1968 Fender Stratocaster (serial no. 240981) that collectors call the “White One,” owing to its Olympic White finish. Though he ate and wrote right-handed, Hendrix usually played guitar left-handed, strumming with his left hand. As seen in the documentary Woodstock, he played the “White One” (and most of his other guitars) upside down, restrung with light-gauge Fender “Rock ’n’ Roll” strings for left-handed playing. Hendrix’s Woodstock amplifier was a UK-built, 100-watt Marshall Super Lead, model 1959, known as the “Plexi” amp, which drove four 4-12 Marshall speaker cabinets that had been specially constructed for the festival.

Between his guitar and amplifier, Hendrix used a series of three effects devices. First came a Vox wah-wah pedal, his use of which is particularly audible in the “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” introduction. The “small Fasel inductor coils in the Italian-made original were an important part of Jimi’s distinctive tone,” explains Paul Balmer. Next, there was a red Arbiter Fuzz Face,

a primitive but effective mini amp, acting as a preamp stage [to overload the Marshall’s front end,] generating a rich harmonic distortion. [Its] germanium transistors were either two NKT275s or [two] AC128s. This detail was important, as was the matching of these wayward early transistors: a good, well-matched pair sounded terrific, but if poorly matched, they sounded like a mistake. . . .

The other [effect] on the Woodstock stage [was] a Uni-Vibe (an early fourstage phaser effect first developed in Japan by the Shin-Ei company): the second “volume pedal”-like device seen in the film footage at Woodstock is part of this Uni-Vibe rig.

Hendrix positioned “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the climax of his set. He began the anthem’s four minute and thirty-eight second-long performance in a relatively subdued manner, with minimal ornamentation of the melody in the course of its first two phrases (that is, through the word “gleaming”). The first instance of what could be described as text painting occurs at the end of phrase 3, on the word “fight,” at which point the undulating melodic motion in his descending run can be heard as a Vietnam-era representation of the conflict that Francis Scott Key had witnessed more than 150 years earlier. From this point, the performance intensifies, and Key’s text provides ample opportunity for Hendrix to dazzle the crowd. At the beginning of phrase 5 (on the word “rockets”), he employs the wah-wah pedal for the first time, launching into a programmatic depiction of a fierce battle. Here, too, he first uses the Strat’s whammy bar, to great effect. (This “tremolo arm” is attached to the guitar’s bridge, allowing the player to produce vibrato. Because he typically played a right-handed guitar upside down, Hendrix, as clearly shown in Woodstock, developed a unique technique.) As the battle rages on, an even longer programmatic passage can be heard at the end of the fifth phrase, following the words “bombs bursting in air.” By the end of the sixth phrase (with the words “flag was still there”), the battle has drawn to a close, and the time has come to bury the dead.

At this point, Hendrix interpolates the first half of “Taps.” “Taps” is a solo bugle call that, in its official version, is performed by members of the US military at military funerals and on a few other occasions. For older audience members, this quotation might also have been reminiscent of the first two lines in the refrain of the well-known patriotic song “Over There,” by George M. Cohan (1878–1942). Cohen wrote “Over There” in 1917 to inspire military enlistment after the US entered the First World War. (The song enjoyed renewed popularity in the early 1940s, with the country’s entrance into WWII.) Quoted below are Cohan’s original lyrics for the refrain:

Over there, over there,

Send the word, send the word over there

That the Yanks are coming, the Yanks are coming

The drums rum-tumming ev’rywhere.

So prepare, say a prayer,

Send the word, send the word to beware

We’ll be over, we’re coming over,

And we won’t come back till it’s over over there.

This moving performance of “Taps” appears on the official YouTube channel of the U.S. Navy Band.

This early recording of “Over There” was made by soprano Nora Bayes on July 13, 1917.

Paired with their arpeggio-laden melody, the first two lines of this refrain comprise an obvious example of word painting: Cohan’s melody resembles a military bugle or trumpet call.

Following Taps, Hendrix concluded his rendition of the national anthem with a rousing performance of its refrain. (Textually, as shown in Chapter 9, the final two lines of each of its four stanzas are very similar.) Here, in a vivid example of text painting on the word “wave,” he uses the guitar’s whammy bar to produce a steadily widening vibrato that clearly depicts a flag waving in the breeze.

Almost immediately, Hendrix’s performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” was widely criticized. Negative commentators focused on its non-traditional aspects, and some accused the guitarist of disrespecting our national anthem. In late August 1969, less than two weeks after Woodstock, Hendrix addressed the issue during a press conference promoting his upcoming benefit concert for the United Block Association (UBA) of Harlem (New York). Having been asked why he had chosen to perform “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the festival, Hendrix responded, comparing his interpretation to earlier, more traditional ones:

Oh, because we’re all Americans. We’re all Americans, aren’t we? It was written and played in a very beautiful, what they call a beautiful state. Nice, inspiring, your heart throbs, and you say, “Great. I’m American.” But nowadays when we play it, we don’t play it to take away all this greatness that America is supposed to have. We play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, isn’t it?

This response is consistent with his others to similar questions about his decision, and taken together, they tend to reveal his iconic performance to be less about partisan politics and more about a longing for peace, a desire that all Americans can embrace. In his September 1969 appearance on The Dick Cavett Show, Hendrix denied that the rendition was “unorthodox,” adding, “I thought it was beautiful.” Looking back twenty years later, Hendrix scholar Charles Shaar Murray praised the performance as “probably the most complex and powerful work of American art to deal with the Vietnam War and its corrupting, distorting effect on successive generations of the American psyche.”

Hendrix appeared on The Dick Cavett Show on September 9, 1969.

“Purple Haze”

After finishing his rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Woodstock, Hendrix transitioned directly into one of his biggest hits, “Purple Haze.” This song will serve as a good example of the psychedelic rock sound developed by Hendrix and his UK bandmates. It will also allow us glimpses of Hendrix the songwriter, the recording artist, and the live performer.

“Purple Haze”

Composer: Jimi Hendrix

Performance: The Jimi Hendrix Experience (1970)

Like many popular songs, “Purple Haze” emerged out of a collaborative experimental process. In late 1966, Hendrix was still seeking to develop his signature sound. The Jimi Hendrix Experience had landed their first hit on the UK charts in December, but Hendrix didn’t think that the song, “Hey Joe,” accurately reflected the band’s character, and he promised fans that the next single would be something special. “Purple Haze” began as a guitar riff—a brief melodic fragment that eventually came to be repeated throughout the final song. Hendrix’s producer, Chas Chandler, thought that the riff had potential and encouraged Hendrix to develop it into a song. According to Chandler, Hendrix finished writing “Purple Haze” in a backstage dressing room on December 26.

On January 11, 1967, Hendrix taught the song to his bandmates and they made the initial recording in just three takes. The process, however, was far from finished. Chandler and Hendrix continued to discuss the track over the coming month, returning to the studio to record additional elements whenever they had an idea. Chandler then applied various effects to the recording. The final song, therefore, was the product of an extended period of studio experimentation, not a single recording session. This method of creating music had only recently become available with the advent of multitrack recording, which allows sounds recorded at different times to be combined.

Although the process by which “Purple Haze” came into the world is complicated, at least it can be explained. The same is not true of the song’s lyrics. When asked what “Purple Haze” was about, Hendrix never gave the same answer twice. Once he said that the song was inspired by “a dream I had that I was walking under the sea.” Another time he claimed that it captured a mythical scene, perhaps “the history of the wars on Neptune.” Yet another time he said that it was a love song. Some have connected it with an episode from Hendrix’s life, who claimed to have been the victim of a voodoo spell cast by a girl he met while living in New York City. Music scholar Harry Shapiro has argued that the song was inspired by a book Hendrix was reading at the time, Frank Waters’ Book of the Hopi (1963), which describes Hopi rituals and legends. Finally, listeners have usually assumed that the song describes the experience of taking hallucinogenic drugs—something that Hendrix and other musicians certainly did, but which they could not explicitly reference in songs for fear of being banned from the airwaves.

To further complicate matters, Hendrix once claimed that “Purple Haze” originally had “a thousand” words, but that Chandler had forced him to reduce the length of the song by cutting verses. (Chandler did in fact help Hendrix to trim his lengthy tracks so that they would be suitable for radio play—a process that they both agreed made the songs better.) However, no additional verses to the song have ever surfaced.

The meaning of the lyrics probably doesn’t matter all that much. Hendrix, after all, was a guitarist, and his songs were primarily vehicles for his virtuosic playing. It is certainly the guitar part that made this song a hit. The guitar introduction to “Purple Haze” features a sequence of dissonant harmonies (better heard on the studio recording than in our performance) followed by an angular melody that rises and falls. Next, Hendrix lays out the harmonic progression that will be heard under the verses—the first chord of which has in fact come to be known as the “Hendrix chord,” due to its scarcity in the playing of others. The guitar is heavily distorted throughout, and Hendrix uses feedback as a musical device.

For reasons of video quality, we will consider Hendrix’s performance of “Purple Haze” not at Woodstock but at the 1970 Atlanta Pop Festival. In some respects, a live performance of “Purple Haze” might be considered inferior to the studio recording: The overdubbed vocals are lost, as are the various post-production effects. What we gain, however, is Hendrix’s extraordinary showmanship. To begin with, he doesn’t play the guitar like other people. In addition to holding the instrument backwards, he employs a variety of unorthodox techniques, including playing passages without the use of his left hand. Even more striking is Hendrix’s sexualized handling of the instrument, which he regularly positions between his legs.