Private: Unit 3: Music for Entertainment

8 Listening at Home and at Court

Esther M. Morgan-Ellis and Louis Hajosy

Today, you can enjoy almost any kind of music in the privacy of your home. In fact, it seems likely that every kind of music is heard through headphones and stereo speakers more often than it is heard live. However, it is important to address the contexts for which music is created, and only certain types of music have traditionally been available for home consumption. In the previous chapter, we examined a series of public concerts and considered musical works that were created for the concert stage. In this chapter, we will focus on musical genres and works that were created explicitly for performance and enjoyment in domestic environments.

We’ve already encountered a few such pieces—Franz Schubert’s “Elf King,” for example (see Chapter 5), which was intended for performance at a living room concert before a small audience. The environment for which this song was created determined many of its characteristics. Because he knew the performance space would be small, Schubert wrote for just two performers. Much later, composers following in Schubert’s footsteps would provide full orchestral accompaniment for their songs, but Schubert used only a piano. At the same time, Schubert’s goals for this song could only be achieved by means of an intimate performance. He sought to communicate an intense drama to a rapt audience. This is not music for a noisy bar or a cavernous hall. Schubert wanted the singer and listener to be physically close and to share an emotional experience.

While we can enjoy public music in private or make private music public (baritone Dietrich Fischer-Diskau’s most famous performance of “The Elf King” was broadcast on television), the experience is enriched by remembering how the music was meant to be consumed. Knowing about the original performance environment also helps us to understand why certain musical decisions were made. Such considerations will apply to all of the diverse examples in this chapter.

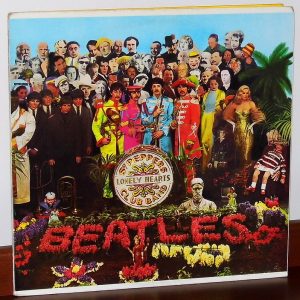

The Beatles, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

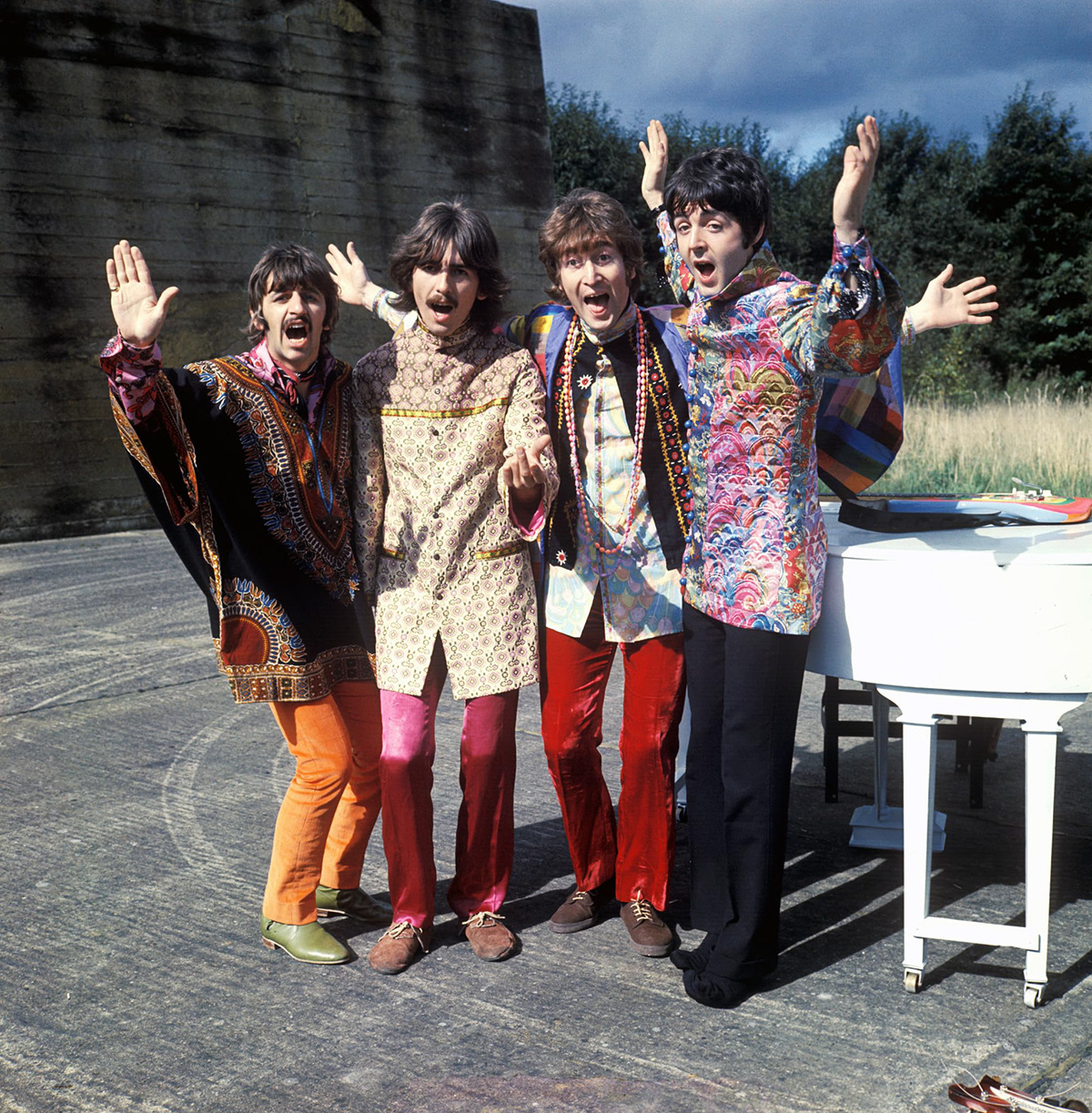

It might seem odd to start with an album by a famous rock ‘n’ roll band who once performed in front of 55,000 fans at Shea Stadium in Queens and appeared frequently on national television. No performers of the era were more public. However, this album represented a deliberate and explicit break with the concert model, and it was intended to be heard through headphones by attentive, isolated listeners.

Background

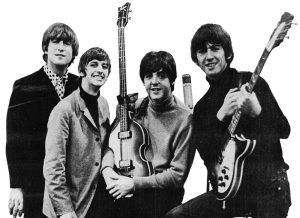

Frequently hailed as the greatest album ever recorded, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) epitomizes a musical work intended for domestic consumption. In fact, before even recording the album, The Beatles themselves knew that its contents would never be performed publicly. From the outset, according to producer George Martin, Sgt. Pepper’s was intended to contain songs that “couldn’t be performed live: they were designed to be studio productions.” With their previous two albums, Rubber Soul (1965) and Revolver (1966), The Beatles had matured beyond the rock ’n’ roll of their early period. (Chronologically and stylistically, Revolver marks the center of the band’s career, and discussions of their discography tend to place it near the middle of a transitional period from Rubber Soul to Sgt. Pepper’s.) The Beatles had become a rock band, and Sgt. Pepper’s represents a continuation and acceleration of their progression away from Beatlemania and the British Invasion era.

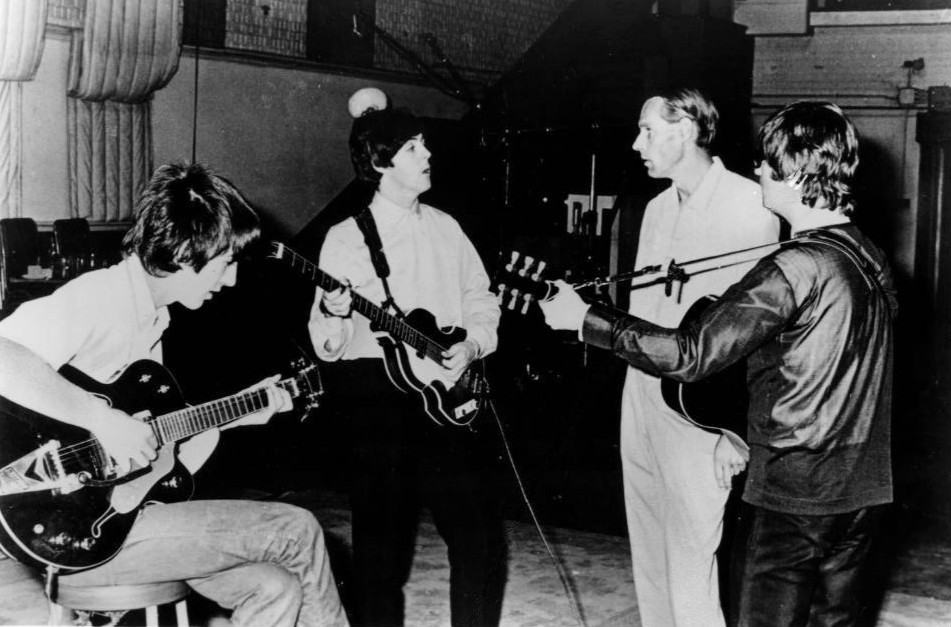

By the time Sgt. Pepper’s was released, The Beatles were well on their way to becoming the most influential band of all time. Along with Rubber Soul and Revolver, it is remembered as one of the first albums of the album era, a period from the mid-1960s to the mid-2000s during which the album, in various formats (LP, 8-track, cassette, CD), was the dominant medium for recorded music. Increasingly, albums came to be seen as more than just cost-effective vehicles for the distribution of hit-single compilations or collections of random songs. Artists had come to view their albums as extended works of art, in which each song was part of a unified whole, and The Beatles were at the forefront of this trend. With Rubber Soul, Revolver, and Sgt. Pepper’s, the band, producer George Martin, and engineer Geoff Emerick succeeded in creating albums that were truly greater than the sum of their parts. (At Martin’s request, Emerick was named The Beatles’ engineer in April 1966, just before the Revolver sessions began.) Each album features songwriting that is more sophisticated and explores a wider variety of styles than its predecessor, and each reveals the band’s ever-growing desire to experiment with the latest technological innovations. The impressive production and engineering skills of Martin and Emerick proved invaluable in this latter regard. By approaching the recording studio as another sort of musical instrument, they greatly facilitated The Beatles’ attempts to realize their grand musical ideas. Although it took several hundred hours to record (an exorbitant amount of time by 1960s standards), Sgt. Pepper’s was a huge hit in the Summer of Love, praised not only for bridging the cultural divide between popular music and high art but also for providing a musical representation of its generation and the contemporary counterculture.

The Beatles began recording Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band on November 24, 1966, in Studio Two at EMI Recording Studios (now Abbey Road Studios), London. Still fresh in their minds were the previous summer’s momentous events. On June 24, 1966, two days after completing their seventh album, Revolver, The Beatles had begun a tour of West Germany, Japan, the Philippines, and North America. The tour was relatively unsuccessful and plagued by weaker-than-expected ticket sales and run-ins with local authorities and protest groups. It ended with what became the group’s final commercial concert, an eleven-song set at Candlestick Park in San Francisco on August 29. By then, each band member had agreed (probably in St. Louis, on August 21) that The Beatles would never again perform publicly. (They did, however, give one last public performance, from the rooftop of the London headquarters of Apple Corps, Ltd., their multimedia corporation, on January 30, 1969.) Many Beatles scholars consider the band’s August 1966 decision to stop touring to be the most important one of their career. Within days of their August 31 return to London, they parted ways to begin a three-month break.

On November 19, 1966, five days before the Sgt. Pepper’s recording sessions began, Paul McCartney conceived and began developing the idea of an Edwardian-era military band, namely, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, whose members would be The Beatles’ alter egos. The inspiration occurred “suddenly,” during his return flight to London from a short safari vacation to Kenya with his then-girlfriend Jane Asher and Beatles assistant Mal Evans. In the following, McCartney recounts the episode:

I got this idea. I thought, let’s not be ourselves. Let’s develop alter egos. [Let’s] actually take on the personas of this different band. We could say, “How would somebody else sing this? He might approach it a bit more sarcastically, perhaps.” . . . It would be a freeing element. I thought we [could] run this philosophy through the whole album: with this alter-ego band, it won’t be us making all that sound, it won’t be The Beatles, it’ll be this other band, so we’ll be able to lose our identities in this.

[Mal and I] were having our [in-flight] meal, and they had those little packets marked “S” and “P.” Mal said, “What’s that mean? Oh, salt and pepper.” We had a joke about that. So I said, “Sergeant Pepper,” just to vary it, “Sergeant Pepper, salt and pepper,” an aural pun, not mishearing him but just playing with the words.

Then, “Lonely Hearts Club,” that’s a good one. [At the time, there were a] lot of those about, the equivalent of a dating agency now. I just strung those [words] together rather in the way that you might string together Dr. Hook and the Medicine Show. All that culture of the Sixties going back to those traveling medicine men, Gypsies. It echoed back to the previous century, really. I just fantasized, well, “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” That’d be crazy enough, because why would a Lonely Hearts Club have a band? If it had been Sergeant Pepper’s British Legion Band, that’s more understandable. The idea was to be a little more funky. That’s what everybody was doing. That was the fashion. The idea was just [to] take any words that would flow.

In late November 1966, when The Beatles began work on their eighth studio album, they had yet to choose its title. During the earliest sessions for what became Sgt. Pepper’s, the band recorded “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane.” When composing these songs, Lennon and McCartney drew inspiration from their memories of Liverpool, the band’s hometown in Northwest England. For instance, Lennon, as a child, had played in the garden of Strawberry Field, a Salvation Army children’s home (now closed) in Woolton, a Liverpool suburb. And Penny Lane is an actual street in south Liverpool: The song’s lyrics vividly describe its associated characters. Also recorded during these early sessions was “When I’m Sixty-Four,” a song from The Beatles’ formative years and the only one of these three that appears on Sgt. Pepper’s. Succumbing to management and record-company pressure, the band and producer George Martin agreed to release “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” as a double A-side single on February 13, 1967. In his Summer of Love: The Making of Sgt. Pepper, Martin calls his agreement to leave these two songs off the album “the biggest mistake of my professional life.”

Despite their exclusion from Sgt. Pepper’s, “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” were crucial in setting its overarching theme, one involving the band members’ childhood experiences in Liverpool. (“Strawberry Fields Forever,” as Martin recalls in Summer of Love, “set the agenda for the whole album.”) In the first week of February 1967, The Beatles recorded what became the album’s title track, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” yet another song evoking nostalgia for earlier times. More importantly, it was also the earliest realization of McCartney’s alter-ego idea from the previous November 19, and he soon proposed that the entire album should represent a performance by the fictional band.

This qualifies Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as one of the first examples of a concept album—an approach to album design that would become increasingly important over the next few years and that persists into the present day. A concept album, like a song cycle (see Chapter 4), brings together a unified collection of songs to tell a story or capture an experience. Although Sgt. Pepper’s does not present a specific narrative, it encourages the listener to imagine that they are present at a live concert—a concert, however, that they soon realize could never take place, due to the diversity of instruments and pervasiveness of studio editing.

“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”

The scene is set by the opening track, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” which opens with ambient noises intended to create the illusion that a show is about to begin. Martin combined crowd noises he had recorded at a theatrical performance with the sounds of an orchestra warming up, which he captured in the studio while recording tracks for use in the album’s final song. Of course, the ambient instrumentals aren’t quite right: We seem to hear strings at the outset, but they are absent from the song itself, which features typical rock band instruments (electric guitars, electric bass, and drums). Our expectations are soon disrupted, however, when an ensemble of French horns joins the soundscape at the conclusion of the first verse. These are hardly at home in a rock lineup, and it is hard to imagine them being played onstage. The entrance of the horns is greeted by a cheer from the crowd, and crowd sounds punctuate the performance, reminding that listener that they are “present” at a live event.

“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Composers: John Lennon and Paul McCartney

Performance: The Beatles (1967)

McCartney’s lyrics—belted in a rock style—also reinforce the setting. He begins by providing a brief history of the band, after which he introduces it by name. Later, with lines like “we hope that you enjoy the show,” “it’s wonderful to be here,” and “you’re such a lovely audience,” he clearly establishes the premise for the album. To further solidify the idea that we are hearing a live concert, McCartney concludes “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” by transitioning directly into the second song. McCartney introduces a fictional singer, “the one and only Billy Shears” (voiced by Ringo Starr), who then launches into “With A Little Help From My Friends” to the sound of applause.

At this point, the concert conceit begins to evaporate. We no longer hear the sounds of the crowd, and we are gradually invited to forget the surroundings made real in the opening seconds of the album. While Starr’s song is fairly conventional in terms of instrumentation and form, the third song begins the journey that will take the listener far away the concert stage.

“Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | Introduction | Triple meter (through 0’47”); key of A major (through 0’31”); Paul’s famous Lowrey organ part. |

| 0’06” | Verse 1 | “Picture . . .”; George enters on tambura at about 0’17” |

| 0’18” | “Somebody . . .” | |

| 0’32” | Bridge 1 | “Cellophane . . .”; key of B-flat major (through 0’50”) |

| 0’42” | “Look . . .” | |

| 0’47” | “Gone”; quadruple meter (through 1’08”) | |

| 0’50” | Chorus 1 | “Lucy . . .” (3 times); key of G major (through 1’08”) |

| 1’06” | “Ahh” | |

| 1’08” | Verse 2 | “Follow . . .”; triple meter (through 1’49”); key of A major (through 1’34”) |

| 1’20” | “Everyone . . .” | |

| 1’33” | Bridge 2 | “Newspaper . . .”; key of B-flat major (through 1’52”) |

| 1’43” | “Climb . . .” | |

| 1’48” | “Gone”; quadruple meter (through 2’10”) | |

| 1’51” | Chorus 2 | “Lucy . . .” (3 times); key of G major (through 2’10”) |

| 2’06” | “Ahh” | |

| 2’09” | Verse 3 | “Picture . . .”; triple meter (through 2’33”); key of A major (through 2’33”) |

| 2’21” | “Suddenly . . .” | |

| 2’31” | Quadruple meter (through fade-out); key of G major (through fade-out) | |

| 2’34” | Chorus 3 | “Lucy . . .” (3 times) |

| 2’48” | “Ahh” | |

| 2’53” | Chorus 3 (repeated) | “Lucy . . .” (3 times); fade-out begins at about 3’02” |

| 3’08” | “Ahh” | |

| 3’13” | Chorus 3 (repeated; partial) | “Lucy . . .” (2 times); fades to silence |

By the time they wrote and recorded Sgt. Pepper’s, The Beatles had experimented with both cannabis and LSD, and the extent to which the band’s use of these psychoactive drugs influenced its creation has long been debated. Of all the album’s tracks, the third, “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” is the one most discussed in this regard. Many believe that the first letters of the nouns in the song’s title, L, S, and D, are a reference to lysergic acid diethylamide, LSD. Lennon repeatedly denied this, maintaining that the title was derived from that of a pastel drawing by his three-year-old son, Julian, that depicted the boy’s nursery-school classmate Lucy O’Donnell. During an episode of The Dick Cavett Show airing on September 21, 1971, Lennon recalled Julian’s presentation of the drawing to him, which Starr witnessed:

This is the truth. My son came home with a drawing, and showed me this strange-looking woman flying around. I said, “What is it?” He said, “It’s Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” and I thought, “That’s beautiful.” I immediately wrote a song about it.

Whatever the case, the song itself is a masterpiece of psychedelic rock, due in no small part to its imaginative lyrics, with their “marmalade skies,” “cellophane flowers,” “rocking horse people,” and “newspaper taxis.” In writing them, Lennon was directly influenced by the literary style of Lewis Carroll’s novels Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (1871), especially the latter’s final chapter (chapter 12), “Which Dreamed It?”

Musically, “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” exemplifies The Beatles’ artistic maturation over the period 1965–67. Its three main sections, the verse, the bridge, and the chorus, are in different keys: A major, B-flat major, and G major, respectively. Following a short introduction, this verse–bridge–chorus structure is heard for the first time, and is then repeated. A second repetition begins, but this time, the bridge is absent: verse 3 leads directly to chorus 3, which is then repeated through the fade-out. Moreover, the song employs mixed meter. The introduction, the verse, and the bridge (except its last measure) are in triple meter, while the bridge’s last measure and the chorus are in quadruple meter, also known as common time.The technique of shifting from triple to quadruple meter one measure before the chorus is also used to connect verse 3 to chorus 3. Each meter-change is accompanied by a noticeable tempo shift.

“Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” also reflects The Beatles’ increasing tendency to utilize sounds and instruments infrequently heard in contemporary rock. The song’s introduction, for instance, features a memorable keyboard part, brilliant in its simplicity, played by McCartney on a Lowrey DSO-1 Heritage Deluxe electronic organ. The ear-catching harpsichord- or celeste-like sound used for this part is (probably) a combination of the organ’s harpsichord, vibraharp, guitar, and musicbox stops. Then, about halfway through the first verse, Harrison enters on the tambura (tanpura), a long-necked, unfretted lute commonly associated with Indian music. Typically, as heard here, the player plucks the instrument’s strings (usually four or five) in a continuously repeating pattern, producing a buzzing, overtone-rich drone. (In Western art music, the repetition of a musical pattern numerous times in succession is called ostinato.)

Indian music’s influence is again evident at the start of the first bridge. Here, as author Peter Lavezzoli explains, Harrison “mirrors Lennon’s [lead] vocal with electric guitar, as if he were playing a sarangi behind a khyal singer.” The Beatles’ guitarist is known to have “liked ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’ a lot.” In discussing his contributions to its arrangement, Harrison highlights the song’s integration of non-Western elements:

I particularly liked the sounds on it where I managed to superimpose some Indian instruments onto the Western music. …I like the way the drone of the tambura could be fitted in there.

There was another thing: during vocals in Indian music, they have an instrument called a sarangi, which sounds like the human voice, and the vocalist and [the] sarangi player are more or less in unison in a performance. For “Lucy,” I thought of trying that idea, but because I’m not a sarangi player, I played it on guitar. …I was trying to copy Indian classical music.

“She’s Leaving Home”

We will pass over the next two songs, although of course they have many points of interest: “Getting Better” includes the Indian tambura and an unusual early electric keyboard instrument called the pianette, while “Fixing a Hole” opens with the sounds of a harpsichord. “She’s Leaving Home,” however, marks the first wholesale departure from the rock-band sound, for the accompaniment is provided exclusively by strings. The arrangement for four violins, two violas, two cellos, string bass and harp was created by Mike Leander, although George Martin was never happy with it. Double tracking on the chorus—a technique by which a melodic line is recorded twice—causes the voices of Lennon and McCartney to multiply, thereby providing a marked contrast with the more subdued singing in the verses.

“She’s Leaving Home” from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Composers: John Lennon and Paul McCartney

Performance: The Beatles (1967)

“Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite”

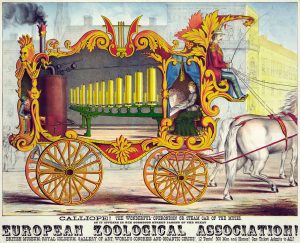

More extraordinary sounds await the listener in the next song, the lyrics of which describe the activities of circus performers. In seeking to evoke a carnival atmosphere, Martin naturally turned to the instrument most closely associated with fairgrounds: the calliope, or steam organ. To bring an actual calliope into the studio, however, would have been impossible, so he instead combined recordings of instruments made on-site with the reedy sounds of the studio organ. The timbral pallette is filled out by harmonium and four harmonicas.

These instruments—and others—are heard at the beginning of the track and in two extended interludes, each of which transports the listener to the scene being described. The first interlude is in triple time—an unusual feature, since the rest of the song is in quadruple time. The change is explained by the line preceding the interlude: “And of course Henry the horse dances the waltz.” We are hearing the music to which he is dancing (and perhaps seeing Henry in our minds). The second interlude has been described by Michael Hannan as having been designed “to conjure up the giddy experience of a hallucinogenic carousel ride.” Any listener is likely to confirm this view, for Martin has overlaid a dense tapestry of recorded calliope sounds that fail to line up to the pulse in a meaningful way. The effect is dizzying.

“Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite” from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Composers: John Lennon and Paul McCartney

Performance: The Beatles (1967)

“Within You Without You”

We must consider, for a moment, the nature of the medium for which Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club was intended. So far, all of the songs we have encountered appeared on the first side of the LP. “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite” closed out that side with its “hallucinogenic carousel ride.” Next, the listener would have to take a brief break from listening in order to turn the record over. What they encountered next would represent the most distant point on their sonic journey.

The North Indian instruments heard in “Within You Without You” are not new to the listener, but Harrison goes further in his efforts to absorb and reflect Indian musical influence, such that this song represents The Beatles’ deepest foray into the world of Indian music. The Beatles’ fascination (especially Harrison’s and Lennon’s) with Indian music and philosophy began in 1965. Like “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” the songs “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown),” from Rubber Soul, and “Tomorrow Never Knows,” from Revolver, contain obvious examples of Indian musical influence. Written primarily by Lennon, all three are firmly rooted in the Western popular music tradition. Their “Indian” elements, though innovative, are essentially superficial, a sort of sonic flavoring, mainly involving the use of non-Western instruments (e.g., sitar, tambura).

“Within You Without You” from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Composer: George Harrison

Performance: The Beatles (1967)

“Within You Without You” features a veritable orchestra of Indian and Western instruments, including three tamburas, two dilrubas (a bowed lute), a sitar, eight violins, three cellos, and tabla (a pair of hand drums). The unusual scales on which the melodies are based reflect Indian influence, as does the fact that the entire song is rooted in a persistent drone. Other Indian-derived elements include the slides we hear between pitches and the use of call and response between solo and grouped instruments. The lyrics convey Lennon’s understanding of Eastern philosophy.

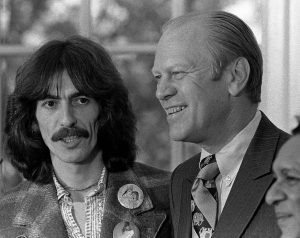

The inclusion, at Harrison’s request, of the images of four Indian gurus on the album’s iconic cover further attests to the culture’s profound impact on the band at this time. The gurus appear there in a collage of several dozen celebrities and historical figures, before which The Beatles stand, posed as the fictional Lonely Hearts Club Band, in their brightly colored Edwardian-era military uniforms.

“A Day in the Life”

Near the end of the second side, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” returns as a reprise. It seems to the listener that this is the end of the concert—a message reinforced by the lines “we hope you have enjoyed the show” and “we’re sorry, but it’s time to go.” The song sounds a little bit different than it did the first time: it’s faster, shorter, and at a lower pitch level. The crowd sounds are back, however, and cheers at the end suggest that the concert has indeed concluded.

Instead, the music transitions directly into a final song—the longest and most complicated song on the entire album. “A Day in the Life” begins with the spare texture of guitar and piano, but upon the words “I’d love to turn you on” the listener is gradually overwhelmed by a sound that grows in volume, pitch, and intensity with inevitable force. Although it is hard to identify, what we are actually hearing is forty orchestral musicians each recorded four times, for a total of 160 tracks. (It was during this recording session that Martin captured the ambient “warming up” noises heard at the beginning of the album.)

“A Day in the Life” from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Composers: John Lennon and Paul McCartney

Performance: The Beatles (1967)

Following the climax of the crescendo, we are returned to what seems to be a totally different song. It certainly bears little relation to what preceded the orchestral noise. This time, the words “I went into a dream” cue the return of orchestral instruments, which now underpin McCartney’s floating vocals. The next section brings back the opening material, which again spills into a cacophonous orchestral crescendo. This time, however, it is followed up with a piano chord—in fact, a thrice overdubbed recording of three musicians playing three pianos—that slowly fades away over the course of forty-three seconds. The last thing we hear is some incidental studio chatter, which was originally cut into the outer groove so that it would loop indefinitely until the listener lifted the tonearm off of the disc.

Legacy

Few musical works in history have enjoyed the success of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. After reaching number one on the UK’s “Official Albums Chart” on June 10, 1967, it remained there for twenty-three consecutive weeks. In the U.S., Sgt. Pepper’s began a fifteen-week run atop the “Billboard 200” album chart on July 1, 1967. Since that time, it has spent hundreds of weeks on both charts. Meanwhile, critical assessments of the album have remained almost universally positive for more than five decades. (To this day, its few negative critics are attacked as heretical pariahs, often publicly shamed by their colleagues.) As author Jonathan Gould explains, the critics’ seemingly endless heaping of praise on Sgt. Pepper’s began immediately after its release:

The overwhelming consensus was that The Beatles had created a popular masterpiece: a rich, sustained, and overflowing work of collaborative genius whose bold ambition and startling originality dramatically enlarged the possibilities and raised the expectations of what the experience of listening to popular music on record could be. On the basis of this perception, Sgt. Pepper[’s] became the catalyst for an explosion of mass enthusiasm for album-formatted Rock that would revolutionize both the aesthetics and the economics of the record business in ways that far outstripped the earlier Pop explosions triggered by the Elvis phenomenon of 1956 and the Beatlemania phenomenon of 1963.

Sgt. Pepper’s has garnered a vast multitude of accolades. At the 10th Annual Grammy Awards ceremony (in February 1968, honoring 1967 releases), for example, it became the first rock album to be named Album of the Year (for The Beatles and producer George Martin). Sgt. Pepper’s also received three other Grammys that night: Best Contemporary Album (again for The Beatles and producer George Martin), Best Engineered Recording—Non-Classical (for engineer Geoff Emerick), and Best Album Cover, Graphic Arts (for art directors Peter Blake and Jann Haworth). The Library of Congress added the album to the National Recording Registry in 2003, in recognition of its cultural, historic, and aesthetic significance, and in 2012, Rolling Stone ranked Sgt. Pepper’s number one in its list of the “500 Greatest Albums of All Time.” As of today, it has sold more than thirty-two million copies worldwide, making it one of the best-selling albums ever released.

Countess of Dia, “I Must Sing”

For most of history, of course, intimate music making has required live performers. As a result, various traditions of song accompanied by one or a few acoustic instruments have arisen in various times and places. We will examine several of these, beginning with the first secular song repertoire ever to be written down: that of the medieval troubadours, who wrote songs in what is now southern France.

Troubadours

In historical terms, troubadours were not professional musicians. They were noblemen and noblewomen who wrote and performed courtly songs for their own entertainment. The term “troubadour” comes from the Provençal language, which was spoken in the Duchy of Aquitaine. It literally means “one who finds,” and was used to describe the work of poets, who were understood not to create their works but to discover them. Troubadours certainly dedicated most of their energy to crafting elaborate verses, but these were always set to music and sung, not recited.

Although troubadours wrote in dozens of distinct genres, they were primarily preoccupied with romantic concerns. The most significant genre of troubadour song was the canso, which expressed the courtly sentiment of fin’amors (“refined love”). Typically speaking, fin’amors was the passion that a knight felt for the lady he served. This passion was romantic and all-consuming, but it could never be satisfied, for the knight was pledged to serve his master and mistress—an obligation that precluded the possibility of intruding upon their marriage. Instead, the knight would suffer in song, lamenting the impossibility of winning the woman he desired but finding solace in dedicating his life to her service.

This ideal of unrequited passion was at the center of Aquitainian courtly life, as we see when we examine the biographies, or vidas, of the troubadours. These short narratives, which were only loosely grounded in historical truth, include few details about the troubadour’s work or life. Instead, they focus entirely on the noble personages whom the troubadour loved and on behalf of whom the troubadour suffered. Take, for example, the vida of Bernart of Ventadorn, the most famous of all the troubadours. His rather long vida is dedicated entirely to his romantic life. It tells us how he first loved the wife of the Viscount of Ventadorn, about whom he wrote all of his songs. Upon the discovery of his passion, however, Bernart was dismissed and joined the court of the Duchess of Normandy—with whom he fell in love, of course, and about whom he wrote many more songs. Upon her departure for England, Bernart reportedly entered an order of monks and died of a broken heart.

Although troubadours are best remembered for their celebrations of idealized romantic suffering, they also sang about more earthly love affairs. The alba was a song about lovers interrupted by the dawn (and the return of the woman’s husband), while the serena concerned a lover impatiently awaiting his partner’s arrival in the evening. In a pastorela, a knight suggested to a peasant girl that they make love; sometimes she acceded, sometimes she did not. In sum, the repertoire makes it clear that troubadours didn’t spend all of their time yearning for unobtainable aristocrats.

The troubadours were active throughout the 12th century, while the Duchy of Aquitaine flourished. During this period, their tradition was primarily oral. They wrote songs in their heads and performed them from memory, and those songs were then carried from place to place by minstrels who learned them by ear. In the early 13th century, however, an effort was made to preserve the songs of the troubadours. This is when the vidas were recorded. In addition, hundreds of poems and a smaller number of melodies were collected in richly-embellished manuscripts.

However, the need to preserve a fading tradition is not the only reason that the songs of the troubadours became the first secular music ever to be recorded. The troubadours and their supporters were also in the unique position of having access to the wealth and education necessary to write music down. In the medieval era, books were difficult and expensive to produce and were therefore enormously valuable. The pages were usually velum (dried sheep skin), and few people had the skills necessary to read or write. Music literacy in particular was largely restricted to clerics. While the troubadour repertoire is prized, we must remember that it offers only a glimpse into the rich traditions of song and dance music that flourished in medieval oral culture.

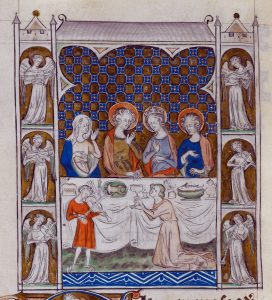

Although the songs of the troubadours were indeed preserved, we still have only shadowy ideas about what this music sounded like. This is because only the melodies were recorded, using a primitive form of notation that did not indicate rhythmic values. The extant manuscripts seem to suggest, therefore, that troubadours sang without accompaniment, but we know from illustrations that this was not the case. Manuscript illuminations depict troubadours and minstrels playing a variety of instruments, including the lute, citole, vielle, rebec, psaltery, harp, shawm, and bagpipes. It is clear that these instruments were used to accompany both dancing and singing. Today, therefore, performers use their imaginations when they approach the troubadour repertoire, creating appropriate accompaniments based on what we know about the instruments, styles, and practices of the time.

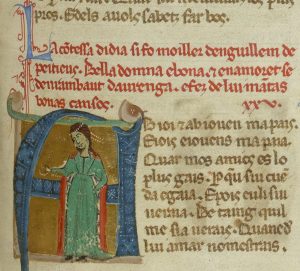

Mystery surrounds not only the songs but their creators. Most of the troubadours are known only by their brief vidas, which are highly unreliable. This is certainly the case of the Countess of Dia, who authored the canso that we will examine. Her vida reads as follows: “The Countess of Dia was the wife of Lord Guillem of Peitieu, a beautiful and good lady. And she fell in love with Lord Raimbaut of Orange and composed many good songs about him.” This vida certainly tells us all that the author felt we needed to know: The Countess was beautiful and good (attributes commonly assigned to noblewomen), she loved a man who was not her husband, and she wrote songs about him. Unfortunately, scholars have been unable to identify the Countess, although competing theories thrive.

“I Must Sing”

The Countess of Dia’s “I Must Sing” is the only song by a trobairitz (the female counterpart to a troubadour) to survive with music. However, it is clear that trobairitz thrived in the courts of Aquitaine, where men and women enjoyed relative equality. Although trobairitz were highly regarded for their poetic skill, they were discouraged from performing their songs in public—an activity considered unseemly for a woman. Instead, male performers would learn and share their music. Trobairitz also had to be a bit more circumspect regarding their declarations of courtly love. While troubadours could be fairly explicit, trobairitz sang in more general terms about the suffering that unrequited love caused them to endure.

“I Must Sing” follows the standard form for a canso. It is in five complete stanzas, the first of which clearly states the lover’s complaint. A partial sixth stanza bids the listener farewell via an imagined messenger and offers a closing moral (“many people suffer for having too much pride”). In the intervening stanzas, the speaker reminds her errant lover of her many fine qualities and washes her hands of any blame for the separation:

I must sing of what I do not want,

I am so angry with the one whom I love,

Because I love him more than anything:

Mercy nor courtesy moves him,

Neither does my beauty, nor my worthiness,

nor my good sense,

For I am deceived and betrayed

As much as I should be, if I were ugly.

I take comfort because I never did anything wrong,

Friend, towards you in anything,

Rather I love you more than Seguin did Valensa,

And I am greatly pleased that I conquered you in love,

My friend, because you are the most worthy;

You are arrogant to me in words and appearance,

And yet you are so friendly towards everyone else.

I wonder at how you have become so proud,

Friend, towards me, and I have reason to lament;

It is not right that another love take you away from me

No matter what is said or granted to you.

And remember how it was at the beginning

Of our love! May Lord God never wish

That it was my fault for our separation.

The great prowess that dwells in you

And your noble worth retain me,

For I do not know of any woman, far or near,

Who, if she wants to love, would not incline to you;

But you, friend, have such understanding

That you can tell the best,

And I remind you of our sharing.

My worth and my nobility should help me,

My beauty and my fine heart;

Therefore, I send this song down to you

So that it would be my messenger.

I want to know, my fair and noble friend,

Why you are so cruel and savage to me;

I don’t know if it is arrogance or ill will.

But I especially want you, messenger, to tell him

That many people suffer for having too much pride.

Translated by Craig E. Bertolet. Used with permission.

As was always the case among troubadours, the Countess of Dia set her poem as a strophic song, meaning that each stanza is sung to the same melody. Although this means that there can be no direct correlation between text and music (since the music repeats), her melody is nonetheless expressive. She uses a standard troubadour form known as bar form, which follows an A A B pattern. The A section starts in the medium range and then descends—perhaps emblematic of the singer’s sorrow. The B section ascends to the song’s highest note by means of a series of leaps, creating a climactic moment before returning to the low range. The song is in the Dorian mode, which is very similar to the minor mode; only a single pitch in “I Must Sing” does not come from the minor scale.

In order to demonstrate the variety that characterizes modern performances of troubadour songs, we will consider two recordings of “I Must Sing.” The first is very simple. The female singer begins without accompaniment, but she is joined by a harp in the second A phrase of the first verse. The harp continues to play for the remainder of the performance. It provides simple harmonies, alternating between two chords derived from the pitches on which the phrases of the melody end. The singer chooses her rhythms based on the meaning of the text and sound of the words, while the harp follows her phrasing. This rendition could easily be performed by a single musician accompanying her own singing—just as we know these songs were often performed in the troubadour era.

“I Must Sing”

Composer: Countess of Dia

Performance: New York’s Ensemble for Early Music (2003)

The second recording is more complex. First, we hear fragments of the melody played on a variety of stringed instruments, including lute, harp, and bass viol. When the singer enters, she interprets the melody with rhythmic freedom while the instruments add flourishes. In between verses, instrumental interludes feature a percussive pulse and the sounds of the ney flute and kanun zither, which perform a metered version of Dia’s melody. Both the ney and the kanun—along with several other instruments heard on this recording—will be discussed in the next section, which addresses court music of the Ottoman Empire. The music director who created this recording, Jordi Savall, is renowned for his recreations of medieval European song using the instruments and performance techniques associated with Middle Eastern music of the same era. It is likely that the two musical traditions had many common elements in the 12th century. While troubadour practices were eradicated, however, those of Middle Eastern courts have persisted into the present.

“I Must Sing”

Composer: Countess of Dia

Performance: Montserrat Figueras with Hespèrion XXI, conducted by Jordi Savall (2010)

Tanburi Cemil Bey, “Samâi Shad Araban”

Where there are powerful rulers, there is music. We might select examples of court music from any of the great empires of history, for all have used music to advertise power, signify elite status, invest ceremonies with dignity, ornament daily life, and entertain guests. Other relevant instances are discussed elsewhere in this book: the jali of West Africa (Chapter 5) were principally occupied with serving the Mandinkan aristocracy.

Here, however, in keeping with the focus of this chapter on unstaged chamber music intended for small spaces and private audiences, we will consider a tradition that developed in the courts of the Ottoman Empire. This example will also help us to understand how troubadour songs (discussed in the previous section) are interpreted by performers today, for they often incorporate the instruments, textures, and ornamentation of Middle Eastern court music. Finally, this example will provide a point of reference for evaluating Pyotr Illyich Tchaikovsky’s exoticized “Arabian” music in The Nutcracker (Chapter 4).

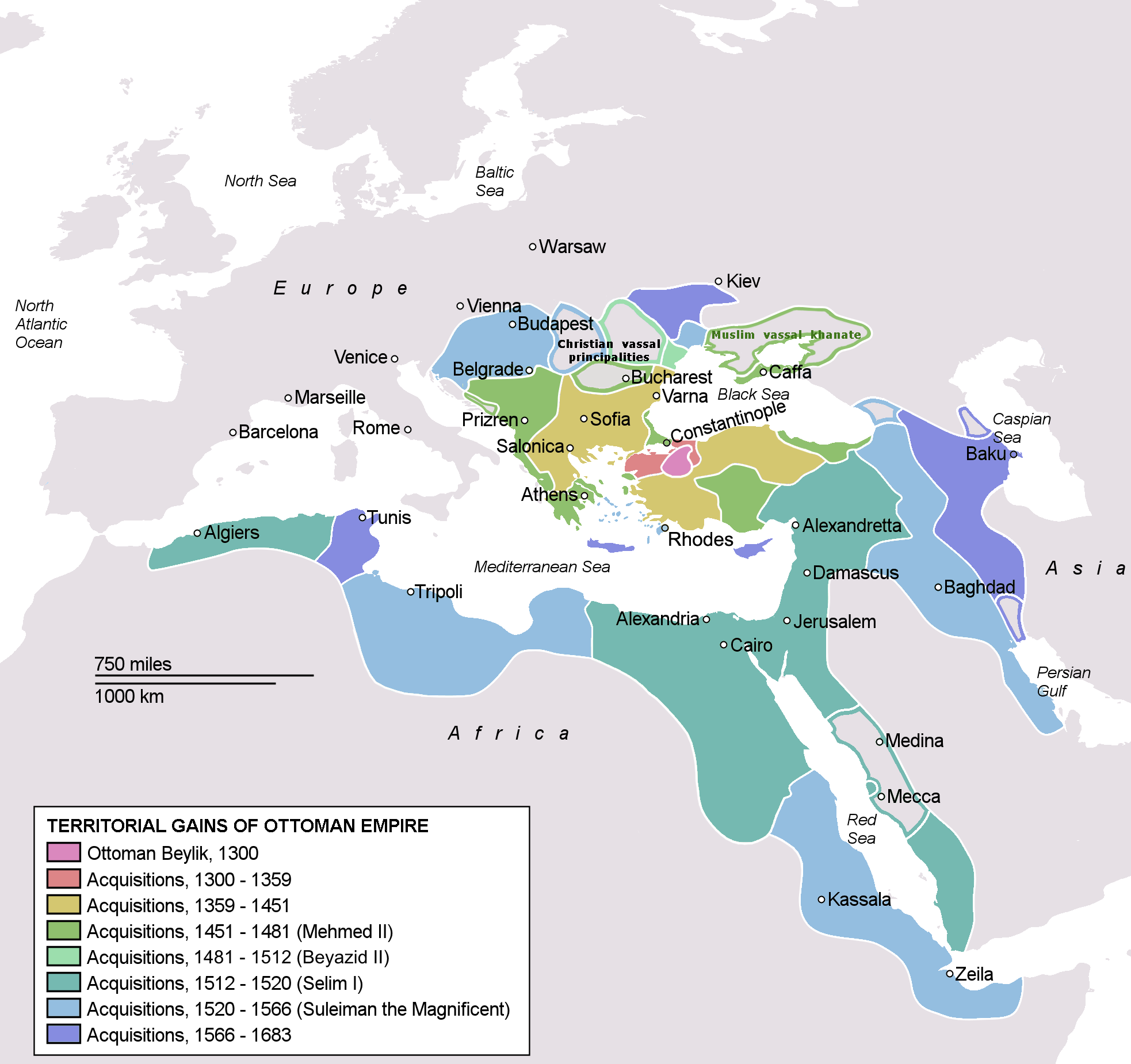

Music in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire was founded in 1299 by the Turkish tribal leader Osman I. In 1453, the Ottomans captured the Christian city of Constantinople, which had until that point been the capital of the Byzantine Empire. That city, known today as Istanbul, became the capital of the Ottoman Empire: a centralized seat from which the sultan (Arabic for “supreme authority”) could expand his reach. The Ottoman Empire achieved the height of its power in the late 16th century, at which point it extended from Central Europe across North Africa and well into the Middle East.

The 19th century, however, saw the Empire’s gradual decline as it ceded power and territory to its neighbors. Following the Great War (later renamed World War I), the Empire was formally dissolved and ultimately replaced by the Republic of Turkey in 1923.

For several centuries, however, the Ottoman Empire mediated between European powers and the Far East. The Western border of the Empire came very near Vienna, which was a major European political and cultural center in the 18th and 19th centuries. As a result, Ottoman music had a significant impact in Europe. The Ottoman military band tradition, in particular, can be identified as the precursor to Western marching bands, while composers like Mozart and Beethoven frequently referenced Ottoman instruments and styles in their music.

The Ottoman Empire certainly cultivated rich musical traditions. Here, we will examine the most elite of those traditions: makam music, which was performed for (and sometimes even created by) the sultan and members of his court. As in most great empires, the Ottoman rulers sought to manage cultural diversity, not eradicate it. As the Empire absorbed citizens from three continents, it simultaneously assimilated their cultural traditions. Ottoman musical practices, therefore, reflected Byzantine, Armenian, Arabic, Persian, and even European influence.

The term makam is itself derived from the Arabic maqam, which describes a system of musical modes. In European music, modes are scales, the most prominent of which in use today are major and minor. A makam, however, is more than just a scale. To begin with, there are many more makams than there are European modes—between 60 and 120. They are difficult to count because makams are always coming and going. An individual makam might fall out of use, or a new one might be developed.

The number of makams is so high because each contains a great deal of information about how music associated with it is expected to sound. A makam determines not only pitches but characteristic melodic motifs, ascending and descending melodic patterns, phrase endings, and the specific tuning of individual notes. This last element can be particularly striking, for the Turkish system divides each whole step into nine possible microtones (the European system divides it into only two). A note that is meant to be just slightly flat or slightly sharp, therefore, will sound out of tune to a Western ear, even though the performer has in fact placed it with perfect precision.

Makam music is performed using instruments that can be found across the Mediterranean region. These include the oud (a type of lute), the kanun (a plucked zither), the ney (an end-blown reed flute), and the rebab and kemençe (both bowed fiddles), although these last instruments have been almost completely replaced by the violin. Percussion instruments are also important, for they mark the rhythmic cycle, known as the usul. These instruments include the pair of pot-shaped kudüm drums, the bendir (a circular frame drum), and the def, which is related to the tambourine. In the performance of makam music, only one of each instrument is typically present, and their unique timbres are easy to discern in the texture.

Ottoman musicians organized their court performances into suites of individual pieces. Such a suite is known as a fasıl, and it might contain six or eight pieces, all in the same makam, totalling about thirty minutes of music. A traditional fasıl is full of variety: It contains different types of songs and several vocal and instrumental improvisations. Although most of the pieces feature a singer, the fasıl starts and ends with lengthy selections for the instrumental ensemble. The introductory peşrev is slow and stately, while the concluding saz semâisi contains passages in a lively dance tempo.

Samâi Shad Araban

We will consider a famous saz semaisi composed by Tanburi Cemil Bey (1843-1916). Cemil Bey was famous for his virtuosity as a performer. Although he began his training on the violin and kanun, he soon gained renown for his skill on the tanbur—a long-necked lute that developed in the Ottoman Empire—and kemençe. Cemil Bey lived late enough that he was able to leave behind recordings, made on 78 rpm discs. These attest to his ability and continue to influence performers today, who still employ techniques that he developed and popularized.

In addition to revolutionizing performance techniques, Cemil Bey left behind a large number of compositions, many of which are among the most frequently performed in the Turkish classical tradition. Although Cemil Bey did not personally serve in the court of the sultan (the Ottoman Empire, after all, was well into its decline during his lifetime), he worked in the forms that had been developed for court entertainment. His “Samâi Shad Araban,” therefore, has the typical characteristics of a saz semâisi, and by examining it we will be able to understand how this type of composition has functioned for hundreds of years. We will also have an opportunity to hear the typical Turkish instruments and consider how they are used in performance.

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | A (Hane 1) | The violin, ney, oud, and kanun all play unique versions of the same melody. |

| 0’36” | Teslim | |

| 1’12” | B (Hane 2) | |

| 1’54” | Teslim | |

| 2’30” | C (Hane 3) | Near the beginning of this passage we hear a “half-flat” pitch that some might perceive as out-of-tune. |

| 3’18” | Teslim | |

| 3’54” | D (Hane 4) | In this passage, the meter changes to triple and short melodic passages are repeated. |

| 5’54” | Teslim | Played by the solo oud. |

| 6’31” | Teslim | Played by the entire ensemble. |

To begin with, we must consider the nature of composition in the Ottoman tradition. Like medieval Europeans (consider, for example, the Countess of Dia), Ottoman performers learned, composed, and taught music without the aid of notation. Although Ottoman music was notated as early as the 17th century, the purpose of notation has always been primarily to record compositions for future reference, and it is seldom used for teaching or performance. Even today, Turkish classical musicians rely on aural and oral processes—that is, listening, imitating, and correcting—to acquire techniques and repertoire.

A typical characteristic of music in oral traditions is variation. When a performer learns a tune by ear, they are likely to introduce minor alterations by accident. However, in the Ottoman tradition, variation is not only accepted but encouraged. The composer expects individual performers to interpret the melody in a way that reflects the characteristics of their instrument, their training, and their own personal preference. As a result, while a performance of “Samâi Shad Araban” is always recognizable, no two musicians will play exactly the same notes.

Another type of variation emerges due to the norms of Ottoman performance practice. A piece of music such as Clara Schumann’s Piano Trio in G minor, discussed at the end of this chapter, is intended for a specific assortment of instruments: one piano, one violin, and one cello. Schumann also used notation to indicate exactly what each performer is supposed to do. Compositions in the Ottoman tradition, however, can be realized using any permutation of the classical ensemble. “Samâi Shad Araban,” therefore, can be performed as a solo or by an ensemble. A typical performance will feature about six performers, with only one playing each of the instruments described above. However, a rendition by a smaller or larger ensemble is perfectly viable.

This flexibility is a characteristic of the heterophonic texture of Ottoman classical music, in which all pitched instruments play essentially the same melody. “Samâi Shad Araban,” for example, can be transcribed (written down using staff notation) as a single melodic line. However, no two instruments play exactly the same pitches. Sometimes the variations have to do with the technical limitations of the instrument: a rebab player, for example, can slide between pitches, while a kanun player cannot. Other variations have to do with training or personal preference, as described above. The result is a complex musical texture in which the listener can easily perceive a core melody, even as the performers constantly alter that melody with diverse shadings and ornaments.

We will hear all of this in our recording of “Samâi Shad Araban.” First, however, we must consider the typical characteristics of a saz semâisi. In terms of form, a saz semâisi always features a repeated melodic refrain (known as a teslim) that follows upon a series of disparate melodic passages (each of which is termed a hane, or “house”). The form of “Samâi Shad Araban” can be summarized as A T B T C T D T, in which T (for teslim) is the refrain.

While each of the hane are melodically distinct, the D hane is markedly different from the others. To begin with, it contains a great deal of internal repetition—each of the first three melodic phrases is repeated at least once. Most striking, however, is that it is in a different meter. While the predominant usul (meter) of a saz semâisi consists of a cycle of ten beats in a moderate tempo, the usul of the D hane has six beats and is performed at a significantly faster tempo. As a result, the penultimate passage of “Samâi Shad Araban” is more energetic and exciting than those that preceded it. This makes the saz semâisi a good piece of music with which to conclude a suite, for it always comes to a rollicking finish.

The melodic instruments in our recording are the violin, ney, oud, and kanun. Because the timbre of each is so different, it is fairly easy to pick the various instruments out of the texture. In addition, each adds unique, improvised ornaments. The kanun player periodically contributes melodic flourishes and rhythmic elements that are not played by the other instruments, while the violin player emphasizes their ability to slide between pitches. The oud is foregrounded near the end of the performance, when it renders a solo version of the teslim before we hear it one last time from the entire ensemble.

The percussion accompaniment to “Samâi Shad Araban”—and, indeed, to any saz semâisi—is not specified by the composer. Instead, the performers use their knowledge of the usul and the melody to improvise an accompaniment that demarcates the rhythmic cycle while also reflecting the character of the melodic phrases. In this recording, we can clearly hear the jingling sounds of the def above the regular beats of the various drums.

Finally, a word about mode. The makam of “Samâi Shad Araban” is indicated by its title, which tells us the type of piece that this is—a saz semâisi—and its mode, Shad Araban. (This is similar to the European convention of naming a piece of music something like Symphony in E Minor.) The pitches of Shad Araban are not particularly similar to those of the major or minor scale. This makam features two intervals of an augmented second: a large interval that is not present in any European scale. It also contains a large number of half steps, the smallest European interval. As a result, melodies in Shad Araban move by intervals that seem alternately cramped and spacious.

This video demonstrates the pitches of Shad Araban:

John Dowland, “Flow, My Tears”

John Dowland (1563-1626) was indisputably one of the finest lute players of his day. Although he was best known for his skill as a performer, he also wrote a great deal of music, both for his own instrument and for viol consort (an ensemble of string instruments that predated the modern violin family). He gained a reputation for writing exceptionally sad songs that celebrated melancholy.

Dowland’s Career

Despite his widely-recognized skill, Dowland was repeatedly frustrated in his attempts to secure a position at the court of Queen Elizabeth I. This might have been due to the fact that he had converted to Catholicism, although Elizabeth, who was tolerant of religious diversity, employed other Catholic musicians. Whatever the case, he spent decades working on the European continent while continuing to publish his music in England. In 1594 he accepted a position at the court of the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. Then, in 1598, he became lutenist at the court of Christian IV, King of Denmark, where he was held in high esteem and paid an astronomical sum.

Dowland returned to England in 1606, but it was not until 1612 that he was finally able to secure a position at the English court. By this time, he not only had an international reputation but had published a wealth of compositions. Writing music served Dowland’s interests in several ways. By producing new music for his own instrument, the lute, Dowland increased his value as a court employee. By publishing music for the lute and other instruments, he created an additional source of income and strengthened his reputation. Finally, by dedicating his publications to wealthy aristocrats, he won their professional and financial support.

“Flow, My Tears”

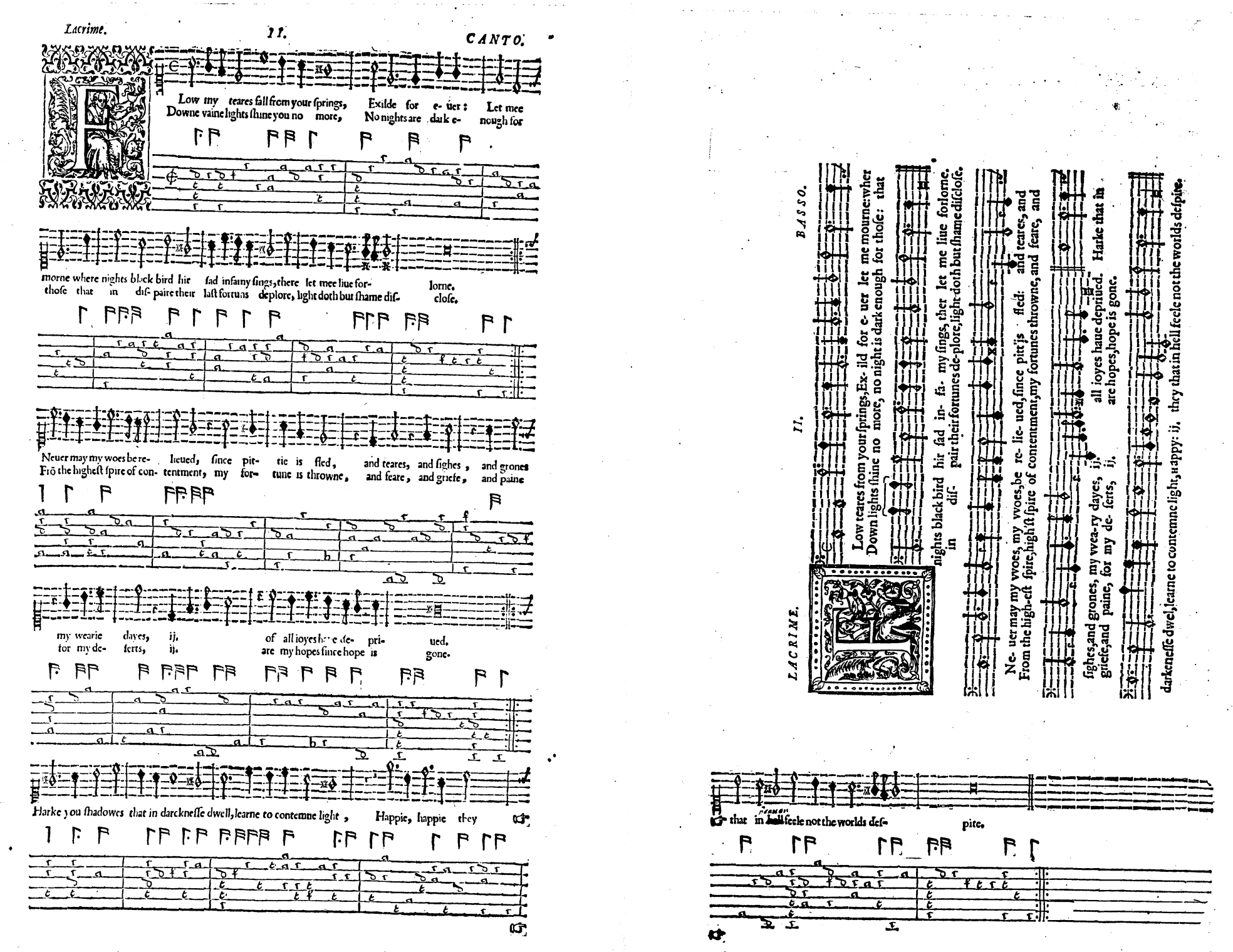

The lute song “Flow, My Tears” provides an excellent example of Dowland’s professional savvy. The composition began life as a pavan for solo lute entitled “Lachrimae” (a Latin term meaning “tears”). A pavan is a type of slow, stately court dance that was popular in Europe at the time. Although Dowland’s music was not intended to accompany dancing, he was often influenced by the characters and styles of dance music. When “Lachrimae” became Dowland’s most popular work, he took the opportunity to capitalize on his success by transforming it into a song.

“Flow, My Tears”

Composer: John Dowland

Performance: Elin Manahan Thomas and David Miller (2007)

Dowland’s lute song “Flow, My Tears” was adapted from this earlier composition for solo lute, entitled “Lachrimae.”

“Flow, My Tears” was first published in Dowland’s 1600 collection The Second Booke of Songs or Ayres (an “ayre” is a solo song with lute accompaniment). Dowland had previously developed a novel approach to typesetting his lute songs, many of which had more than one vocal part. Before Dowland, it was common practice to publish each vocal and instrumental part to a piece of music in a separate book, known as a “part book.” Each performer therefore needed to possess the correct book, and could only see their own part. Dowland began printing all of the parts in a single book, which could be laid out on a table before the performers. In this way they could all read from the same page.

This tells us something important about how Dowland’s music was used: He was writing for groups of friends or family members, who would perform his music gathered around a table in the home. Although today you are more likely to hear Dowland performed by professionals in a concert setting, that was never what he had in mind. He was producing music for the domestic entertainment market—music to fill the long evening hours when there was little else to do.

The layout of “Flow, My Tears” can help us to visualize a home performance, even if one cannot read the music. The lute and primary vocal part are paired together, since they might be performed by the same person. The lute part, as was typical of the era, is printed using tablature instead of staff notation. Lute tablature, much like guitar tab today, indicates where the fingers of the left hand go on each string of the instrument. It also includes rhythms. The extra vocal part is printed on the second page, and it faces in a different direction. This was for convenience: The additional singer would sit to the right of the lutenist, along the adjoining edge of the table.

“Flow, My Tears” is a prime example of Dowland’s work in terms of affect, form, and style. To begin with, the text is characteristically gloomy:

Flow, my tears, fall from your springs!

Exiled for ever, let me mourn;

Where night’s black bird her sad infamy sings,

There let me live forlorn.

Down vain lights, shine you no more!

No nights are dark enough for those

That in despair their lost fortunes deplore.

Light doth but shame disclose.

Never may my woes be relieved,

Since pity is fled;

And tears and sighs and groans my weary days

Of all joys have deprived.

From the highest spire of contentment

My fortune is thrown;

And fear and grief and pain for my deserts

Are my hopes, since hope is gone.

Hark! you shadows that in darkness dwell,

Learn to condemn light

Happy, happy they that in hell

Feel not the world’s despite.

Dowland—who wrote his own words—expresses the most profound hopelessness. The final stanza, in which he argues that even those who are in hell should be glad they are not in his position, takes this sentiment to the extreme. We do not, however, need to take this text too seriously. Melancholy was in fashion at the time. When people sang “Flow, My Tears,” they indulged in emotional role-playing that probably had a cathartic effect.

Dowland’s ayre is in three parts. The first two stanzas are sung to the same music, while the next two are sung to a new tune. The final stanza has its own music, which provides a satisfying conclusion. The resulting form, therefore, is A A B B C. Although the song can be performed by a solo singer with lute accompaniment, Dowland also provided an additional vocal part in the bass range, which would allow another performer to join in.11 The vocal and instrumental parts are highly independent: Each is equally difficult and has its own rhythms and melodies.

In this rendition, we hear Dowland’s song with both the primary soprano melody and the option bass melody.

The music, which is in the minor mode, is highly expressive. The opening melody descends, providing a musical portrayal of falling tears. In the B section, Dowland sets his list of sorrowful expressions (in the third stanza: “and tears, and sighs, and groans”) to a melody that ascends by leap, accompanied by echoes from the lute. This technique communicates the passion and suffering behind these complaints. The highest pitch of the melody arrives in the C section with the word “happy”—but Dowland’s descending melody indicates that he does not feel happiness himself.

In 1604, Dowland capitalized on the success of “Lachrimae” and “Flow, My Tears” yet again by publishing a further version of the work for viol consort. It appeared in a volume dedicated to Anne, the new Queen of England—an effort by Dowland to secure that elusive court position. This time, the composition became the first of a set of pavans entitled Lachrimae, or Seven Tears, all of which begin with the descending “tears” motif that we heard in the lute solo and song. The first pavan in the collection, “Lachrimae Antiquae” (“Ancient Tears”), is essentially identical to “Lachrimae” and “Flow, My Tears.” The additional six pavans explore different musical possibilities that are introduced by the “tears” motif. All are profoundly mournful in character. As if feeling the need to cement his reputation for melancholy, Dowland followed the set of Lachrimae pavans with a composition entitled Semper Dowland semper Dolens: Latin for “Always Dowland always mournful.”

“Ancient Tears”

Composer: John Dowland

Performance: Hespèrion XXI, conducted by Jordi Savall (1987)

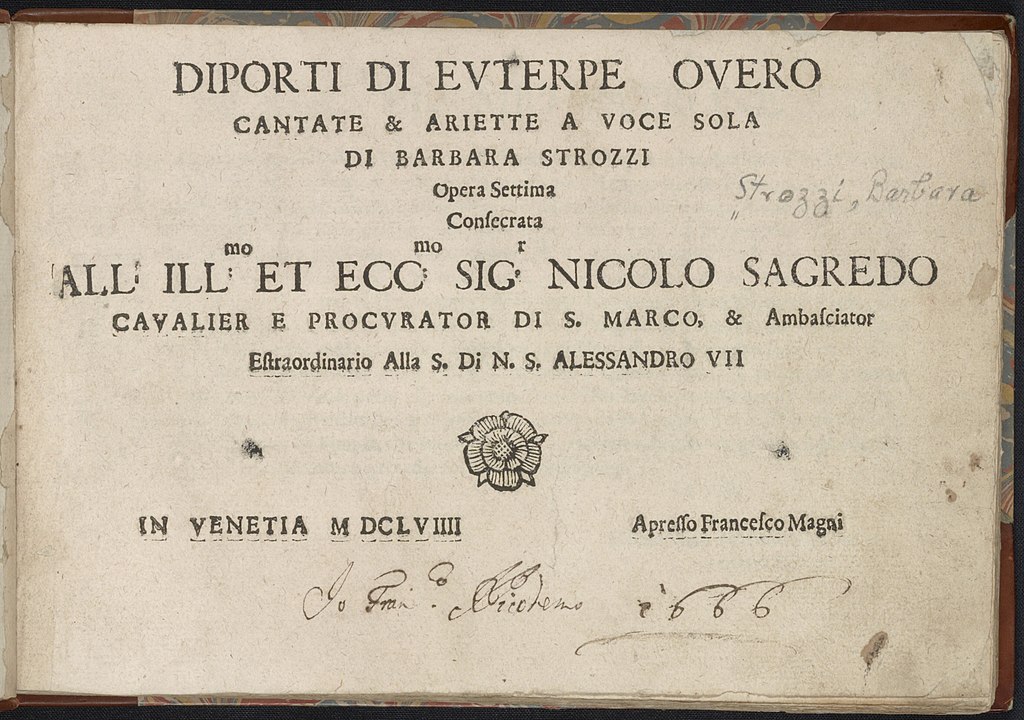

Barbara Strozzi, My Tears

Barbara Strozzi (1619-1677), like Dowland, was a gifted performer who wrote music for her own use. Also like Dowland, she favored sorrowful laments that showcased her gifts, as a performer and composer, for extravagant emotional expression. Most of her vocal works concerned suffering caused by unrequited love. Strozzi’s unique social position, however, meant that her artistic motivations were quite unlike Dowland’s, while her geographic and temporal distance from him—Strozzi lived in Venice, and her career began shortly after Dowland’s death—meant that her style was significantly different.

Strozzi’s Career

Strozzi was the adopted daughter of the renowned poet and cultural luminary Giulio Strozzi. Her mother was a servant in Giulio’s household. Although Strozzi’s birth certificate indicates that her father was unknown, it was almost certainly Giulio himself. This sort of arrangement was not unusual in 17th-century Venice. Giulio himself was the illegitimate son of an illegitimate son, while Strozzi would in turn have four children out of wedlock. Whatever the case, Giulio took an active interest in his daughter’s career as a singer and composer, writing texts for her to sing and facilitating her private performances before the city’s artistic elite.

In 1637, Giulio established a formal academy dedicated to music over which his daughter presided. Academies were an important facet of intellectual life in Venice and other Italian-speaking cities of the era. They were not formal schools but, rather, gatherings of educated citizens who came together for discussion and debate. Giulio’s named his association the Accademia degli Unisoni. This translates to “Academy of the Like-Minded,” but also incorporates a music-themed pun on the word “unisoni,” which can mean “unison” in the sense of multiple voices singing the same notes. At the academy meetings, Barbara Strozzi suggested topics for debate, judged the forensic skill of participants, awarded prizes, and performed as a singer (probably accompanying herself on the lute).

Although Strozzi embarked on a singing career just as opera was becoming big business in Venice, she never appeared on the opera stage. This is important. Although opera offered roles for women, taking to the stage meant social exclusion. A woman who performed in public was assumed to be a prostitute—and indeed, Strozzi herself faced such accusations as her fame grew. By confining her activities to the private sphere, she retained greater social capital. Her decision to perform only in domestic settings also influenced Strozzi’s work as a composer, which focused on the chamber genres of aria (a strophic song) and cantata (an extended semi-dramatic work for soloist with accompaniment).

While it was typical for 17th-century Italian singers to write their own music, Strozzi pursued the task with unusual resolve. In fact, she published more solo vocal music than any other Venetian composer of her era. In total, she completed and published an astonishing eight single-author volumes of vocal music. Most of this was secular music with Italian texts (some of which she might have written herself), although she also produced one collection of sacred works with Latin texts. Her volumes, which were published between 1644 and 1664, were highly regarded and widely consumed, and many of her most successful compositions were included in collections alongside the work of other great composers. While Strozzi performed before small groups of connoisseurs in a domestic setting, therefore, her music was also available for others to perform at home for their own entertainment, or for gatherings of family and friends.

My Tears

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | Refrain – “My tears…” | The melody starts high and descends via an unusual, tortured scale in a representation of falling tears; the singer embellishes the line with a variety of ornaments. |

| 0’39” | Recitative – “Why do you not let burst forth…” | The recitative passages are characterized by frequent changes in tempo and mood; there is no steady pulse; painful harmonies communicate the speaker’s suffering. |

| 3’01” | Arioso – “And you, sorrowful eyes…” | The music settles into a triple meter. |

| 3’30” | Refrain | |

| 4’03” | Aria – Verse 1: “Alas, I yearn for Lidia…” | The Aria is in quadruple meter. |

| 4’46” | Verse 2: “Because I welcome death…” | The Aria music repeats with new text. |

| 5’31” | Recitative – “But well I realize…” | |

| 5’55” | Instrumental interlude | This interlude was not composed by Strozzi, but it is not inappropriate in a performance of her cantata, the accompaniment to which is largely improvised. |

| 6’45” | Arioso | Again, the music settles into a triple meter; the accompaniment centers on a four-note descending pattern. |

| 7’56” | Refrain | The singer repeats the entire opening passage of the cantata (Strozzi herself indicated only that the refrain should be repeated). |

My Tears (Italian: Lagrime mie) appeared in Strozzi’s seventh volume of music, which was published in 1659 and bore the title The Pleasures of Euterpe (in the mythology of ancient Greece, Euterpe was the Muse of Music). Pietro Dolfino’s text is a lament for a beloved—Lidia—who has been imprisoned by her disapproving father:

My tears, why do you hold back?

Why do you not let burst forth the fierce pain

that takes my breath and oppresses my heart?

Lidia, whom I so much adore,

Because she looked on me with a pitiable glance

is imprisoned by her strict father.

Between two walls

the beautiful innocent one is confined,

where the sun’s ray can’t reach her;

and what grieves me most,

and adds torment and pain to my agony,

is that my beloved

suffers on my account.

And you, sorrowful eyes, you don’t cry?

My tears, why do you hold back?

Alas, I yearn for Lidia,

my idol whom I so much adore;

she’s captured in hard marble,

she for whom I sigh and yet do not die.

Because I welcome death,

now that I’m deprived of hope;

Ah, take away my life,

I pray to you, my bitter pain.

But well I realize that to torment me even more

Fate denies me even death.

Since it’s true, oh God,

that vicious Destiny

thirsts only for my wailing,

My tears, why do you hold back?

Translation by Jennifer Gliere. Used with permission.

Like many secular cantata texts, this one features a refrain—”My tears, why do you hold back?”—that appears three times: once at the beginning, once in the middle, and once at the end. The melody to which the words “my tears” is sung descends from the top of the singer’s range, dripping down in a vivid impression of falling tears. It is full of tortuous intervals and sigh-like ornaments that communicate the singer’s distressed emotional state.

After the opening refrain, the singer carries on in the recitative style, allowing the rhythm and meaning of the text to determine her phrasing. Strozzi continues to employ text painting, such as with the drawn-out, descending chromatic line on the word “pain” (Italian: “dolore”) and the gasping pause in the middle of the word “breath” (Italian: “respiro”). Strozzi finally settles in to a metered rhythm with the passage on the text, “And you, sorrowful eyes, you don’t cry?” This type of music—more structured than recitative but less formal than an aria—is termed arioso. Again, Strozzi employs text painting in the form of repeated, descending sighs.

This is followed by the refrain, which leads into the aria. This is the most formal part of the cantata and the only passage of music in which two stanzas of text are sung to the same melody. The text concerned begins with “Alas, I yearn for Lidia” and concludes with “I pray to you, my bitter pain.” The final passage of the text is set to music that continues to shift and bend in accordance to the singer’s baleful emotions. The last thing we hear is the refrain—evidence that the singer’s suffering has not lessened.

Franz Joseph Haydn, String Quartet, Op. 33, No. 2 “The Joke”

Over the course of the 18th century, the demand for domestic music continued to grow. Instrumental music, in particular, saw a rise in popularity as entertainment for the concert hall, the court, and the home. New genres of instrumental chamber music came into existence, the most important of which was the string quartet. Chamber music differs from orchestral music in three important ways. First, it requires only a few players—usually between two and eight. Second, each of those players has their own part, while in an orchestra whole sections of string players are assigned the same part. Finally, chamber music does not require a conductor. Chamber music, therefore, is suitable for small spaces and emphasizes communication between the individual performers.

A string quartet is a type of chamber ensemble composed of two violins, a viola, and a cello. (The term “string quartet” can refer either to a group of players or to a composition.) Although today professional string quartets give concerts and make recordings, the genre was at first oriented primarily toward amateurs, who purchased sheet music and played at home for their own entertainment. Quartets also provided background music for dinners and social gatherings. The most important early composer of string quartets was Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), whose creative contributions to the genre set the standard for generations to follow.

Haydn’s Career

Haydn was born to working-class parents in a remote Austrian village. Neither his father (a wheelwright) nor his mother (a cook) had any musical training, but they recognized their son’s talent and arranged for him to live with a relative who could provide educational opportunities. Then, in 1739, the music director at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna—Georg von Reutter—heard Haydn sing and offered him a position in the Cathedral choir. For the next nine years, Haydn lived with Reutter, during which time he studied and performed music.

When Haydn’s voice broke in 1749, however, he was suddenly out of a job, and he spent several difficult years trying to scrape together a living as a freelance musician. In mid-18th century Vienna, there were few opportunities for a musical career outside of church or court employment. In 1757, Haydn finally obtained the latter when he became music director for Count Morzin. His fine work with the Count’s private orchestra won him a similar position four years later with the Esterházy family, whom he served for the remainder of his life.

The position of music director for the Esterházys was among the most desirable in the German-speaking world. (Although Haydn served informally as music director from 1761, he was not officially awarded the title until his predecessor passed away in 1766.) The Esterházy family was both wealthy and powerful, exercising great influence within the Habsburg Empire. In addition, Prince Nikolaus I, who headed the family from 1762 until 1790, was a great music lover and ardent support of Haydn. For this reason, Haydn was granted an unusual amount of creative freedom, and his work was met with appreciation. All the same, Haydn was a servant. As such, he was obliged to perform a variety of duties and occupied a low social rung.

Haydn did not just compose music. He was responsible for all musical entertainment, large and small, that took place in the Esterházy household. This included the weekly staging of an opera and two concerts, special performances in honor of guests, and the provision of chamber music for domestic entertainment. Prince Nikolaus was a musician himself: He played an unusual instrument called the baryton, which resembled a bass viol with extra strings that could be plucked. Although the baryton was never popular and soon disappeared altogether, the fact that it was favored by the Prince meant that Haydn had not only to compose music for the instrument but to accompany the Prince when he played. In total, he produced about 200 chamber works for baryton, most of which are trios for baryton, cello, and viola (Haydn’s instrument). The baryton part is always prominent, but never too difficult—as suited the Prince’s abilities and desires. These pieces are seldom performed today, and it is easy to look on them as a wasted effort. They remind us, however, that Haydn often composed on command, and that his own artistic inclinations were secondary to the requirements of his employer.

As a servant in the Esterházy household, Haydn followed the Prince as he moved between the various Esterházy estates. Principal among these were the ancestral palace in Eisenstadt (now in Eastern Hungary) and a new summer palace, Eszterháza, built by Prince Nikolaus in 1766. Although both palaces were well-equipped for musical performances, they were far from the urban center of Vienna, and Haydn’s duties therefore meant that he was isolated from musical trends. As a result, he developed a unique approach to composition, innovating in terms of form and style. His fame slowly grew, and in 1779 he found himself in a position to renegotiate his contract with the Esterházys. Under the new terms, he was free to take outside commissions and to publish his music, which had previously been the property of his employers.

String Quartet, Op. 33, No. 2 “The Joke”

Among the first of Haydn’s publications were a set of string quartets, labelled as his Opus 33 (“opus” is the Latin word for “work,” and it is often used to indicate the order in which published compositions appear). The label indicates that this was Haydn’s thirty-third publication, but of course he had composed a great deal more music than that. Most of his works, however, were intended for the private use of his employer and were therefore never published. But when it came to the world of commerce, it made sense for Haydn to publish chamber works: There was a thriving market for sheet music intended for use in domestic entertainment.

Haydn’s Opus 33 string quartets were dedicated to the Grand Duke Paul of Russia, and they were first performed in the Viennese home of his wife. In the dedication, Haydn explained that these quartets were composed in a “new and special manner.” While this is exactly the sort of thing that a composer might say for the purpose of improving sales, it is true that Haydn’s Opus 33 quartets are different from those that came before. Early quartets were essentially violin solos with accompaniment; in many cases, a professional was hired to take the first violin part, while amateurs filled in the others. The first violin is still prominent in Opus 33, but all of the parts are important and interesting, and they pass motifs from one to another. The resulting texture resembles a civilized conversation between intellectual equals—a musical representation of the rational discourse that was so valued during the Enlightenment era.

We will see all of this at work in the second quartet from Haydn’s Opus 33 collection, which bears the subtitle “The Joke.” This subtitle did not come from the composer himself, but rather from the Viennese publishing firm Artaria. Publishers often gave nicknames to instrumental works in this period, which otherwise were designated only by number. A nickname drew attention to a composition and gave the consumer an idea about its characteristics. Nicknames still help listeners today, for they tell us what a piece of otherwise abstract instrumental music is “about.” We should always, however, take them with a grain of salt.

Haydn’s Opus 33, No. 2 quartet was subtitled “The Joke” because of its fourth movement, which concludes with a bit of unmistakable musical comedy. The joke here is so obvious, in fact, that even listeners with no particular knowledge of music will get it. We should take a moment to marvel at the capacity of pure sound to be humorous. The quartet, of course, contains no words. It communicates purely through musical syntax, and the joke works by playing on our expectations regarding form, pulse, and phrasing.

Movement IV

The fourth movement is in rondo form, meaning that a refrain returns throughout. In Haydn’s time, this was a typical form for a final movement, and his listeners (and players) would have quickly recognized it. This would establish certain expectations—in particular, the expectation that the movement would end with a complete statement of the refrain.

String Quartet, Op. 33, No. 2 “The Joke,” Movement IV

Composer: Franz Joseph Haydn

Performance: Borodin Quartet (2010)