Unit 2: Music for Storytelling

4 Sung and Danced Drama

Esther M. Morgan-Ellis and Alexandra Dunbar

The notion that characters in a staged drama might periodically break out into song or dance is fundamentally strange. All the same, sung and danced dramas permeate our lives, and they have for a long time. Even if you do not regularly visit the opera or ballet, you have likely seen Frozen or The Little Mermaid. Films such as these fit squarely into a tradition of musical theater that extends back for hundreds of years.

Musical drama, as the examples in this chapter will demonstrate, is highly diverse. It can be tragic or comic. It can be realistic or self-consciously artificial. It can be emotionally compelling or merely entertaining. It also encompasses endless variety in musical style, and it can be difficult to draw lines between genres. The examples in this chapter might variously be described as “musical theater,” “opera,” or “ballet” (a term that both European and Javanese performers use to describe their dance drama traditions). However, there are many overlaps between these categories. European ballet first developed as a part of opera, for example, and many operatic traditions include dancing. Dance dramas often include singing—something that is true of both examples in this chapter.

The most difficult categories to differentiate are “musical theater” and “opera.” For example, one does not hear Frozen—even in its live, staged version—referred to as an opera. But why not? Because it is in English? Lots of operas are in English. Because it has spoken dialogue? So does Mozart’s The Magic Flute, discussed below. Because the music is written in a popular style? The Italian opera composer Giuseppe Verdi was responsible for the greatest hit tunes of his day. The most substantial difference between “musical theater” and “opera,” as those categories are understood today, has to do with the training of the performers on the one hand and the venues in which they perform on the other. However, these categories are already shaky, and they will continue to change as new styles of sung and danced drama are developed and popularized.

We encourage the reader of this chapter to approach each example on its own terms, without undue preconceptions about genre. Whether we are talking about New York City in 2015 or Mantua in 1608, it is always helpful to consider the cultural context in which the work was created. Who was the audience, and how were they prepared to understand and appreciate what they saw onstage? Although our examples are diverse, each effectively uses music to enrich the storytelling.

Sung Drama: Lin-Manuel Miranda, Hamilton

Hamilton is considered by many to be the greatest American musical theater production of the current era. The musical tells the story of Alexander Hamilton, an immigrant who travelled from the West Indies to the American colonies before the time of the American Revolution, and who came to be one of the founding fathers of the United States and the first Secretary of the Treasury under George Washington. The musical is based upon the biography by Ron Chernow (b.1949), Alexander Hamilton, published in 2004.

Miranda and Hamilton

Hamilton is the singular creation of the actor, writer, and musician Lin-Manuel Miranda (b. 1980), who, in addition to premiering the title role, wrote the music and lyrics. Miranda is one of the biggest musical theater celebrities of his generation, having won multiple Emmys, Grammys, and Tony Awards for his music, lyrics, and performances. Much of Miranda’s work is influenced by his origins. As the child of parents of Puerto Rican descent, he grew up in a largely Latino neighborhood in Inwood, New York City, regularly visiting family in Puerto Rico. His musical preferences—Miranda grew up listening to salsa and American musicals (such as West Side Story)—reflected both an early interest in his musical heritage and a fascination with the stage. Miranda was gifted musically and academically, attending the highly competitive primary and secondary schools at Hunter College before enrolling at Wesleyan University.

In his theatrical work, Miranda foregrounds his multi-cultural upbringing and Latino identity. As a director, he has always made a conscious decision to cast actors from various cultural and racial backgrounds. This feature of Hamilton has created some controversy, given the historical fact that the men and women represented in the musical were primarily white. Miranda, however, has defended this approach by drawing parallels between his casting and musical decisions. Just as he did not attempt to write music in the style of the 1770s, he did not attempt to create a visual image representative of the 1770s. Miranda’s Hamilton was created to represent America in the current age. He makes the point that the United States was founded by immigrants. The founding fathers themselves—despite their skin color—were either immigrants or the children or grandchildren of immigrants. Hamilton himself was born in the West Indies, coming to America at a young age to make a name for himself. What is more American than that?

The musical numbers in Hamilton incorporate hip-hop beats and rap. The use of popular styles in a musical is not unique to Hamilton: Hair (1967) and Jesus Christ Superstar (1970) were the first modern-era musicals to incorporate rock styles, and Lin-Manuel Miranda had already used rap and hip-hop in his first musical, In the Heights (on Broadway from 2008 to 2011). In writing Hamilton, Miranda found that rap was not only musically exciting but also very useful, for he was able to fit more words into a shorter span of time. Hamilton the man was known for being poetically loquacious. In addition, rap allowed Miranda to incorporate a large amount of information from Chernow’s biography, in addition to Hamilton’s own words. The entire musical is 150 minutes long, but includes over 20,000 words.

Miranda also uses music to communicate with the Hamilton audience in ways that both complement and transcend the script and stage action. One of his favorite techniques for doing so is allegory, or the use of musical sounds to signify hidden meaning. We will address several ways in which Miranda employs instruments or musical styles in an allegorical manner.

Allegory

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’0″ | Introduction “You say…” | King George III of England addresses America to a homophonic accompaniment of sustained piano chords in a four-chord descending pattern. |

| 0’42” | Verse 1 “You’ll be back…” | The accompaniment switches to short harpsichord accents; the overall tone of the text becomes more sinister, which offers an unusual juxtaposition with happy music. |

| 1’15” | Hook “Da-da-da-da-da…” | This catchy passage is sung to nonsense words and is reminiscent of the outro of The Beatles’ “Hey Jude,” which is similar in terms of key and melodic arc. |

| 1’29” | Bridge “You say our love is draining…” | Stop-time accompaniment; double entendre on the word “subject” at 1’46”. |

| 2’12” | Verse 2 “You’ll be back, like before…” | Same musical material as Verse 1; harpsichord returns to the front of the mix, one octave higher than before; tempo slows, emphasizing text, until the word “Love” at 2’46. |

| 2’46” | Hook/Outro “Da-da-da-da-da…” | The performer is joined in this catchy tune by the rest of the cast members on stage. |

There are several additional musical allegories in Hamilton. Let us consider, for example, the number “You’ll Be Back,” which is sung from the perspective of King George III. The music for this number is in the style of 1960s British Invasion pop. (Incidentally, The Beatles—the most famous and influential of the British Invasion bands—prominently featured harpsichord in their 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.) Again, Miranda makes a connection between a British musical style (an invasive one at that) and an imperialistic British character. But that’s not all: Miranda further uses the pop genre to heighten the impact of his character’s words. King George sings this number to a personified America. The music is relentlessly upbeat, as if expressing the emotional state of a delirious ex-boyfriend who cannot grasp that the relationship is over. The text, which is quite disturbing at times, is hilariously juxtaposed with the some of the happiest and tuneful music of the show.

Let us also consider Miranda’s use of the harpsichord. Miranda writes for two keyboard instruments in his musical: the harpsichord and the piano. The two instruments really did not coexist in history. During the course of the 1700s, the harpsichord was gradually replaced by the fortepiano, which was itself an early predecessor to the piano. In Hamilton, however, we do not hear a fortepiano but rather a modern, 20th-century piano—an instrument historically separated from the harpsichord by over one hundred years. The harpsichord, therefore, represents an old way of life—and, more particularly, an old way of conducting politics. Specifically, Miranda uses the harpsichord to represent British rule before the revolution.

The sound of the harpsichord was, historically speaking, the sound of the 18th-century British monarchy. In order to draw a historical comparison, we might consider the music of George Frederic Handel. Handel served as music director (German: Kapellmeister) to the German Prince George of Hanover, who later became King George I of England. While living in London, Handel composed many great works for the King, most notably his Water Music and Music for the Royal Fireworks. Handel was also one of the best-known and highly celebrated harpsichordists of his time. It is therefore fitting that the harpsichord should represent King George III, England, political oppression, and a deranged narcissistic ex-suitor.

G.F. Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks incorporates the harpsichord in a way that is typical of 18th-century European music.

We encounter this allegory in several musical examples. In “Farmer Refuted,” Bishop Samuel Seabury, accompanied by harpsichord, defends his decision to remain loyal to England and begs Hamilton to do the same. “You’ll Be Back” begins with King George III singing to a subdued piano accompaniment. When his lyrics turn sinister, however, we hear the harpsichord enter. In both of these cases, therefore, the sound of the harpsichord is a symbol for the old-fashioned values of the British monarchy.

In “Farmer Refuted,” Miranda uses the harpsichord to symbolize loyalty to England.

Cyclicism

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’0″ | Introduction “They say…” | Same introductory chords as the original introduction, despite plot changes. |

| 0’24” | “I’m perplexed…” | Unusual harmonies. |

| 0’42” | “John Adams” is spoken in surprise. | |

| 0’45” | Verse 1 “I know him…” | Begins with the same tune and feel of Verse 1 from “You’ll Be Back,” but there is no harpsichord; instead, the texture consists of plucked strings, which recall the sound of the harpsichord but offer a warmer timbre; harpsichord returns to the mix in the background at 0’54” on the words, “Years ago.” |

| 1’18” | Hook | Only one iteration of this, unlike before, and there is no “everybody” joining in. |

King George later returns to perform “I Know Him.” This song is a musical reprise of the first number he sang (“You’ll Be Back”). At this point in the musical, the Revolution is long over and John Adams has been elected president. The harpsichord can still be heard, but it is less prominent than it was in “You’ll Be Back.” Instead, it is lurks behind a texture that consists primarily of strings played pizzicato. This is significant: England (harpsichord) has lost the war and King George (harpsichord) no longer rules over the Americans.

“I Know Him” is not the only example of a musical reprise. Indeed, in crafting the score to Hamilton, Miranda sought to unify the various parts of the work using cyclical techniques. Hamilton contains many musical ideas that harken back to earlier points in the work. This approach to creating a narrative can be compared to Wagner’s use of leitmotifs. For example, the opening of the musical begins with a narrative rapped by Aaron Burr: “How does a bastard […] grow up to be a hero and scholar?” Miranda treats this passage from Aaron Burr’s opening number, which is entitled “Alexander Hamilton,” as a leitmotif, which later returns in “A Winter’s Ball,” “Guns and Ships,” “What’d I Miss,” “The Adams Administration,” and “Your Obedient Servant.” Despite the recurrence of musical material, however, each of these numbers has a distinct character. In “What’d I Miss,” the borrowing takes on a swinging feel as the once-straight sixteenths of the opening become dotted. In “Your Obedient Servant,” on the other hand, the tone is darkened by tremolo strings and the omission of the snaps that were previously heard on offbeats: Burr, now downright angry, is resentful of Alexander Hamilton.

The opening phrases of “Alexander Hamilton” become a leitmotif and return throughout the work.

Success

Upon its Broadway premiere in 2015, Hamilton immediately sold out. As of 2019, it continues to be nearly impossible to secure a ticket, the aftermarket prices of which have soared to record-breaking levels. The musical is currently on tour to cities across the globe, including Puerto Rico and London, England. It has won numerous awards, including ten Lortel Awards, three Outer Critic Circle Awards, eight Drama Desk Awards, the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best New Musical, and an Obie for Best New American Play.

The Origins of European Opera

European opera was born in the city of Florence in the late 16th century. Beginning in the 1570s, a group of intellectuals began meeting in the home of Count Giovanni de’ Bardi to discuss artistic matters. They called themselves the Camerata (a name derived from the Italian term for “chamber”), and today are referred to as the Florentine Camerata. The members of the Camerata were courtiers, composers, poets, and scholars, and they were concerned with the modern development of artistic forms. In particular, they believed that the arts had become corrupted, and that artistic expression could only be revived by returning to the principles of ancient Greece. Where music was concerned, however, ancient Greece could offer only limited guidance. While many theoretical and philosophical treatises on music survive, very few compositions were preserved, and we don’t really know what those would have sounded like. Resurrecting the musical practices of ancient Greece, therefore, is a tricky endeavor.

The members of the Camerata drew much of their inspiration from the work of Girolamo Mei (1519-1594), a Roman scholar and the leading authority on ancient Greece. In his 1573 treatise On the Musical Modes of the Ancients, Mei argued that all ancient Greek poetry and drama had been sung, not spoken. He also wrote about the extraordinary power that music had over the listener. His descriptions fascinated the Florentine intellectuals, who felt compelled to develop a modern approach to sung drama. Their aim was to recapture the emotional impact that, according to Mei, sung plays had once had on audiences.

The leading music theorist of the Camerata was none other than Vincenzo Galilei (1520-1591), father of the famous astronomer Galileo Galilei. In order to facilitate sung drama, Galilei sought to develop a new approach to writing vocal music that imitated dramatic speech. It would be modelled on the way in which actors used variations in pacing and pitch to expressively declaim text from the stage. Such music would be free of repetition, of course, since every note would be uniquely tied to the word it illuminated. The rhythms would be derived from the text, while the melodies and harmonies would portray the emotional content. Today, this style is termed recitative, for it more closely resembles dramatic recitation than typical singing.

Of course, a solo singer needs accompaniment. Although Galilei and his colleagues did not invent basso continuo, they did adopt it as the ideal vehicle for supporting sung text. The term “basso continuo” (which translates to “continuous bass”) refers to a style of accompaniment that came to be used in almost all music of the Baroque period (ca. 1600-1750). When a composer writes an accompaniment in the form of basso continuo, they indicate only the bass line and harmonies, which are usually to be played by at least two instruments. They do not usually specify instruments or exact pitches of each chord, which are chosen on the spot by the performers. An instrument that can play chords—harpsichord, organ, and lute were most common—is required, while an instrument that can play a bass line—cello or bassoon, perhaps—is usually included.

Members of the Camerata began experimenting with short sung dramas in 1589, while the first full-length opera—now lost—was composed by Jacopo Peri (1561-1633) in 1597. In 1600, Peri created Euridice, an operatic portrayal of the Orpheus myth. This work, which survives, consists almost entirely of recitative, as does a second version of Euridice produced by another member of the Camerata, Giulio Caccini (1551-1618), in 1602. (The two men were colleagues and collaborators, but also saw themselves as being in competition with one another.)

All of these developments took place in Florence, and were supported by the Medici court. Peri’s Euridice, for example, was created and staged to celebrate the marriage between King Henry IV of France and Maria de Medici. From its inception, opera was understood to be aristocratic entertainment. It upheld noble values and catered to refined musical tastes. It also offered the opportunity for luxurious spectacle in the form of fantastical costumes and scenery.

Wofgang Amadeus Mozart, The Magic Flute

Over the next few centuries, opera became the most prominent form of public entertainment across all of Europe. Although the practice was first developed in Italian-speaking cities, it soon spread to France, England, and Germany, where new forms of opera were developed that catered to local tastes and languages. Italian opera remained so dominant, however, that it was performed—most often in its original language—in every European country. Opera was not truly dethroned as the West’s favorite form of entertainment until talking pictures became mainstream in the 1930s.

Although the variety and riches of the European opera tradition can reward a lifetime of study, we will examine only one more example here. This example was chosen for its historical significance, its intrinsic interest, and the many ways in which it contrasts with early opera. While early operas were serious operas written for court performance in the early Baroque style, The Magic Flute (1791), composed nearly two hundred years later, is a comic opera created for commercial, public performance, and it exemplifies the pinnacle of the Classical style. It is also the work of the most important opera composer of the era: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791).

Mozart’s Career

Mozart was born into a musical family in the city of Salzburg. His father Leopold was a composer and violinist at the court of the Archbishop of Salzburg. Leopold was successful in his career, but he soon realized that his children possessed greater talent than he did. He subsequently abandoned composing to focus on their education. Mozart had an older sister, Marianne, who was his equal as a child prodigy. Both children mastered the harpsichord and fortepiano (a predecessor to the modern piano), while Mozart also became an expert violinist. Beginning in 1762, Leopold took his children on extensive tours to perform for heads of state across Europe. Marianne, however, was forced to abandon public performance when she became old enough to marry. Although there is some evidence that she composed music later in life, she was never given the opportunity to pursue a career.

Mozart, on the other hand, was expected to follow in the footsteps of his father, and upon the conclusion of his final tour in 1773 he took a job at the Salzburg court. Mozart, however, was dissatisfied with the provincial life he led. His exposure as a child to the great cities and courts of Europe had whetted his appetite for cosmopolitan excitement. He also wanted greater personal freedom, and resented being subservient to an employer. In 1781, he quarrelled with the Archbishop of Salzburg and was released from his position. Although his father was disappointed and concerned, Mozart was elated. He immediately moved to Vienna, an important center of politics and culture in the German-speaking world, and set out to build an independent career for himself.

In the late 18th century, there were few opportunities for a freelance musician to make a living. Most composers were employed by a court or church. Mozart, however, was able to capitalize on his fame as a child prodigy, and he had many marketable skills. He taught private piano lessons—although only to the elite young ladies of the city, and for a high fee. He wrote music for publication and accepted commissions. And he put on regular concerts of his music, each of which featured an appearance by the composer himself at the piano in the performance of a new concerto.

Finally, Mozart wrote operas in every genre of his day. He was fluent in various operatic styles and experienced in the conventions of the musical stage: Mozart, after all, had composed and premiered his first opera at the age of 13. In Vienna of the late 18th century, there were audiences for both Italian and German opera. Italian opera was divided into the old-fashioned opera seria (“serious opera”), which told heroic stories of gods and kings, and the newer opera buffa (“comic opera”), which portrayed characters from various social classes in humorous situations. The Magic Flute, however, is an example of a Singspiel (“sing-play”): a German-language comic opera with spoken dialogue and catchy songs. Of the three genres, Singspiel was the least respectable and sophisticated.

Mozart poured most of his energy into opera buffa. In collaboration with the court librettist Lorenzo da Ponte, he created three works—The Marriage of Figaro (1786), Don Giovanni (1787), and All Women Do It (Italian: Cosí fan tutte; 1790)—that have maintained a central place in the operatic repertoire ever since. Although all three of these operas contain comical characters and situations, each conveys a moral and is essentially serious in its purpose. The same is true of Mozart’s last opera, The Magic Flute (1791).

In the final years of his career, Mozart struggled to make a living. Despite early success, he found that his audiences had largely evaporated by 1787. This was due both to the vagaries of fashion and economic difficulties. Whatever the cause, he was no longer able to sell concert tickets, and was forced to abandon his rather lavish lifestyle. He and his wife moved to less expensive lodgings, gave up their carriage, and sold many of their belongings. At the time Mozart received the commission to write The Magic Flute, therefore, he was eager to increase his income. Although 1790 saw a general improvement in Mozart’s fortunes, he became ill while in Prague for the premiere of his final opera seria, The Clemency of Titus (1791), and died on December 5, just a few weeks after the premiere of The Magic Flute.

The Magic Flute

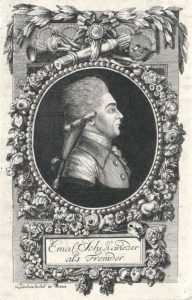

The Magic Flute was largely conceived by the man who commissioned Mozart’s participation in the project, Emanual Schikaneder. Schikaneder was the head of a theatrical troupe that performed at the Theater auf der Wieden, which was located in the Wieden district of Vienna. He and Mozart had known each other for many years, and Mozart had contributed music to several of his collaborative productions. Acting in his role as impresario, Schikanader had a hand in every step of the opera’s development: he came up with the idea of staging a series of fairy tale operas, wrote the libretto for The Magic Flute, assumed financial responsibility, acted as director, and played one of the leads. He is even reported to have made suggestions to Mozart that were incorporated into the score.

Although The Magic Flute can certainly be described as a fairy tale, it is a fairy tale with a political message. In particular, The Magic Flute embodies Enlightenment values, celebrating the triumph of reason over superstition and the moral equality of individuals from different social classes. It also contains multiple references to Freemasonry, which, in late-18th century Vienna, was committed to the furtherance of Enlightenment ideals. Both Mozart and Schikaneder were Freemasons. The Masonic elements include various symbols that featured in the original set design, references to the four elements (earth, air, water, and fire), fixation on the number three, and the tale’s setting in Egypt. Mozart also incorporated the rhythmic knock of the Masonic initiation ritual into his overture.

The plot, in a much simplified form, is as follows: The curtain rises on Prince Tamino fleeing from a serpent. Although he is rescued by three female attendants to the Queen of the Night, he awakens to find Papageno, a bird catcher, who takes credit for defeating the monster. When the women return, they chastise Papageno and show Tamino a portrait of Princess Pamina, the Queen’s daughter. He immediately falls in love with her, but is told that she has been kidnapped by the evil sorcerer Sarastro. The Queen herself appears to tell Tamino that he can marry her daughter if he rescues her. The Queen’s attendants give each of the men a magic instrument to help in their quest: a flute for Tamino and a set of bells for Papageno.

At the end of Act I, Tamino finds his way to Sarastro’s temple, but there he learns that the sorcerer is in fact benevolent, and that it is the Queen of the Night who has evil intentions. Sarastro had taken Pamina in order to protect her from her mother’s influence. Tamino and Pamina finally meet, and Pamina reciprocates his affection. Sarastro, however, refuses to permit the union before Tamino has completed a series of trials (based on Masonic ritual) to prove his spiritual worthiness.

Act II sees conflict between Pamina and her mother and suffering as Pamina awaits Tamino’s successful passage through the trials. The magic flute and bells each serve their respective holders as they seek personal fulfillment. In the end, the two lovers reject the evil influence of the Queen of the Night and join Sarastro’s enlightened brotherhood. And Papageno, who mourns his lonely existence, is rewarded for his faithfulness with a wife: Papagena.

The Magic Flute is rich with comedy, provided by Papageno (and, in a few scenes, the equally ridiculous Papagena), and the opera as a whole is highly entertaining. Most of the characters, however, are serious in purpose, and the story itself certainly carries a message.

The Queen of the Night represents forces that seek to suppress knowledge and clarity in favor of fear, insularity, and irrationality. Some scholars have identified her with the Roman Catholic Empress Maria Theresa, and have interpreted the opera as an attack on Catholicism. This is contentious, however: On the one hand, the Catholic Church was opposed to Freemasonry, but on the other, Mozart himself was a devout Catholic. Whatever the specifics, the Queen of the Night certainly embodies anti-Enlightenment values. Sarastro, on the other hand, is the wise, generous, and benevolent head of state. He exemplifies the political principle of rule by an Enlightened monarch, which many at the time believed to be the ideal form of government. He grants agency and freedom to his subjects, but demands that they hold themselves to high intellectual and moral standards. In the end, the protagonists—Tamino and Pamina—choose modern, Enlightened thinking over the beguiling superstitions of the past.

The opera conveys other messages as well—not all of which are so palatable. Women are certainly not portrayed in a positive light. The realm governed by the evil Queen is entirely female, while the light-filled court of Sarastro is predominantly male. Although Pamina eventually joins Tamino in his trials, her role is to support him: The couple’s salvation relies primarily on his strength of character, and several musical numbers reinforce the idea that a wife must be subservient to her husband. The other female lead, Papagena, is literally a gift to a male character.

Likewise, the opera takes an ambivalent stance toward class distinctions. On the one hand, it portrays low-class characters in an essentially positive light. Papageno might be a buffoon, but he is on the side of good and capable of exhibiting strong moral character. This is an advance on previous operas, in which servants existed only to serve. At the same time, the low-class and high-class characters are kept at a distance from one another. Although Pamina and Papageno are friends and at one point sing a duet about the value of marriage, there is no question of them ending up together. A princess must marry a prince, while a bird catcher must marry within his own social class. Papageno is treated with the loving condescension that all members of his class supposedly deserve.

The Magic Flute, like many operas, also has a race problem. The synopsis above omitted the character of Monostatos, a black man who repeatedly threatens Pamina with sexual assault. Although he initially serves Sarastro as head of his slaves, he defects to the Queen’s side in hopes of winning Pamina for himself. And of course, the fact that Sarastro keeps slaves should also raise eyebrows.

The Magic Flute was a product of its time and place, but all of these issues must be addressed in modern stagings. One of the strengths of live theater is that scripts can be reinterpreted by directors and actors. The challenges of doing so, however, have not been trivial. Many operatic narratives promote social values that are no longer widely accepted. Many also portray non-Western characters or societies in demeaning ways. The inclusion of non-white characters also provides interpretive challenges. While the practice of blackface performance, in which a white actor uses make-up to portray a character of African descent, has been condemned as racist in almost all spheres for the past half century, it is still sometimes used on the opera stage.

Opera companies continue to perform The Magic Flute, however, because the music is delightful. (A clever director can address most of its messaging problems—for example, Monostatos does not have to be black.) The arias that Mozart produced for this opera are unusually diverse and entertaining. This was the case for several reasons. To begin with, he was writing for a commercial theater that attracted a middle-class audience. Most of his listeners were looking for a fun night out, not a transcendent artistic experience. In addition, not all of the actors in Schikanader’s troupe had equivalent musical capabilities. Some were highly-trained opera singers, but others—including Schikander himself, who played Papageno—could barely carry a tune. Mozart, therefore, carefully tailored his writing to each individual singer.

“I am a bird catcher”

With this in mind, we will examine four selections from The Magic Flute. We will begin with Papageno’s first number, “I am a bird catcher.” This is the aria that Papageno sings to introduce himself to Tamino. In it, he sings about his simple life, wandering the countryside in search of birds, and expresses his wish to be equally adept at capturing the hearts of young women. The music created by Mozart effectively communicates Papageno’s character, for he writes what is effectively a strophic folk song. It is in a cheerful major mode and contains only the simplest of harmonies, while the jaunty tempo establishes Papageno’s carefree attitude. We hear Papageno’s flute, which he uses to attract birds, in the second half of each of the two verses.

“I am a bird catcher” from The Magic Flute

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Performance: Hermann Prey with the Staatskapelle Dresden, conducted by Otmar Suitner (1967)

In addition to being dramatically appropriate, this music is also easy to sing. The orchestra begins by playing the entire melody, and the singer, upon entering, is doubled by the violins. Both of these features would have greatly helped Schikaneder give a successful performance. In addition, the vocal range is very small, spanning only a single octave, and positioned comfortably for an average male (not too high or low). Finally, the melody moves mostly by step, with few difficult leaps. Although the role of Papageno is always sung by a highly-trained professional in modern productions, his arias could easily be learned by almost anyone.

Other members of Schikaneder’s troupe were more skilled. In fact, the unusual capabilities of the actors who played the Queen of the Night and Sarastro inspired Mozart to write arias that continue to challenge modern singers. At the same time, the music sung by these two characters accurately reflects their respective roles in the drama.

“O Isis and Osiris”

The role of Sarastro was created for the bass singer Franz Xaver Gerl. Gerl had trained in Salzburg, and might have studied with Mozart’s father. He had an unusually low voice, which Mozart took into consideration. Sarastro’s introductory aria, “O Isis and Osiris,” comes at the beginning of Act II, and its music and text both serve to establish his noble character. Sarastro calls upon the ancient Egyptian gods, Isis and Osiris (both prominent figures in Masonic lore), to guide and protect Tamino and Pamina in their pursuit of wisdom. The text exhibits his profound spiritual commitment to Enlightenment principles and his generous concern for others. The music is slow and deliberate, emphasizing Sarastro’s stability and power. Although this is a strophic aria in two verses, like the one sung by Papageno, it is certainly not a folk song—the melody and harmonies are both too sophisticated. Finally, the extremely low range makes this aria inaccessible for any but a trained singer with unique capabilities.

“O Isis and Osiris” from The Magic Flute

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Performance: Kovács Kolos with the Orchestra of the Hungarian State Opera House, conducted by Pál Varga (1970)

“Hell’s vengeance boils in my heart”

The music that Mozart created for the Queen of the Night is different in every respect. Once again, we must start by considering the original singer, soprano Josepha Hofer (and Mozart’s sister-in-law). Hofer was a singer of extraordinary skill, and she possessed an unusually high vocal range, of which Mozart took full advantage. We will examine the Queen of the Night’s Act II aria, “Hell’s vengeance boils in my heart,” in which she threatens Pamina for refusing to kill Sarastro. While Sarastro exhibits self-control with his singing, the Queen enacts her all-consuming rage. The most remarkable passages of her aria have no words at all, but rather require the singer to leap from pitch to pitch in the highest range using only repeated vowel sounds. Here we encounter a paradox: Although the Queen of the Night is the opera’s villain, her dazzling displays are the highlight of the show. Sarastro’s music is drab and forgettable in comparison.

“Hell’s vengeance boils in my heart” from The Magic Flute

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Performance: Sumi Jo with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Roberto Paternostro (2009)

“Ah, I feel it, it is vanished”

Finally, we will hear from Pamina. This role was created for Anna Gottlieb, who was only 17 when The Magic Flute premiered. (Later in life, Gottlieb specialized in parody roles that required her to ridicule operatic sopranos.) Pamina’s major aria, “Ah, I feel it, it is vanished,” comes in the middle of Act II. She has just been in the presence of Tamino. When she tried to speak with him, however, he refused to respond. She believes this to mean that he no longer loves her. In fact, Tamino is undergoing one of his trials, which requires a vow of silence. Pamina does not know this, and sings a mournful aria about her heartbreak and desolation.

“Ah, I feel it, it is vanished” from The Magic Flute

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Performance: Dorothea Röschmann with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Claudio Abbado (2005)

A sparse orchestral accompaniment combines with the minor mode to convey her emotions. The soprano solo soars unaided into the heights, for Gottlieb certainly did not need to be doubled by an instrument. Unlike the Queen of the Night, however, Pamina keeps her emotions under control: She is despairing, but noble.

Speaking more broadly, we can hear the ideals of self-control and rationality in all of Mozart’s music. These are hallmarks of the Classical style. Composers working in this period preferred balanced phrases, sparse textures, predictable chord progressions, and elegant melodies. Just as the Enlightened individual placed a high value on rational discourse, the music of this period valued orderliness over emotional expression. Mozart certainly sought to convey a wide range of emotional states, but he never abandoned the rational parameters of his art.

Danced Drama: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, The Nutcracker

We’ve already encountered one ballet by a Russian composer: Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Now we will examine another. Stravinsky and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikvosky (1840-1893) are, after all, two of the best-known ballet composers. The most famous choreographers and dancers have been mostly Russian as well. Ballet, however, originated not in Russia but in France. We will begin, therefore, with the story of how this art form ended up thriving nearly two thousand miles away from its birthplace.

Ballet

Ballet’s origins can be traced to European courts of the 15th and 16th centuries, where dance became increasingly formalized and dramatic. Early ballets, however, were quite different from the art form we might be familiar with: Dancers wore regular shoes and clothing, the steps were taken from participatory court dances, and spectators usually joined in for the finale. Court ballet reached its pinnacle under Louis XIV, who ruled France from 1643 to 1715. He was an avid dancer, and frequently took leading roles in the productions. Louis XIV also sponsored the first professional ballet company, which was attached to the Paris Opera. The two genres—opera and ballet—were closely related in this period: French operas always contained extended dance numbers, while court ballets included singing.

Ballet as we know it today emerged in the second half of the 18th century, when a series of reforms were enacted by ballet master Jean-Georges Noverre. Noverre sought to make ballet more expressive and realistic by replacing the heavy costumes with light, form-fitting apparel, doing away with masks, and introducing the use of pantomime and facial expressions to communicate dramatic elements. The early 19th century saw the invention of the pointe shoe, which allows female dancers to balance on their toes, and the tutu, which accentuates their graceful movements and reveals the legs.

Soon, however, ballet in France was faltering. In seeking to compete with opera, ballet promoters were not successful. Ballet’s association with the aristocracy made it distasteful to French audiences of the late 19th century, and it was generally considered to be less expressive than opera—and therefore inferior. Ballet might have vanished completely were it not for Russian interest in the art form. Beginning in the late 18th century, Russian courts sought to establish their cultural credentials by importing European art forms. First, they brought in Italian opera. In the mid-19th century, they turned to French ballet.

Tchaikovsky’s Career

At first, the Russian ballet establishment was managed by French choreographers, scenarists, dancers, and composers. Gradually, however, Russians took over, and ballet became a distinctively Russian art form. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was among the first Russian ballet composers, and his three masterpieces—Swan Lake (1877), Sleeping Beauty (1890), and The Nutcracker (1892)—are still frequently performed today.

Tchaikovsky, however, did not particularly care for his ballet scores, and he disdained their popularity. He would much prefer to have been remembered for his six symphonies, which he considered to be his greatest works. Tchaikovsky also wrote programmatic orchestral pieces, operas, and chamber music—in fact, he composed in all of the prominent European genres of the 19th century. Unlike Russian composers such as Modest Mussorgsky (discussed in Chapter 6), who rejected European influence, Tchaikovsky sought to follow in the European tradition.

Tchaikovsky was firmly entrenched in Russia’s European-style musical establishment. As a young man, he was at first frustrated in his desire to pursue a career in music by the fact that there were no opportunities to study music in Russia. He instead embarked upon a career in the civil service, but in 1862 was able to enroll in the first class at the newly-opened St. Petersburg Conservatory. He impressed his teachers, and upon graduating was offered a teaching position at the Moscow Conservatory, which opened in 1866. Tchaikovsky went on to establish an international reputation as a composer, although he faced criticism at home for not being “Russian enough” in his musical expression.

It is no surprise that Tchaikovsky did not care for ballet work, for in the creation of a ballet, the composer found himself at the bottom of the hierarchy. Most of the creative work was completed by the scenarist (who outlined the dramatic contents of the ballet) and the choreographer (who designed the dance). The Nutcracker was conceived of by the renowned scenarist Marius Petipa, who chose and adapted the story, decided how it would be told through the ballet medium, and established a character for each of the dances. He went so far as to provide Tchaikovsky with the exact tempo and duration for each number, leaving the composer with little opportunity for creative expression. All the same, Tchaikovsky—who, while working on The Nutcracker, wrote to a friend that “I am daily becoming more and more attuned to my task”—was able to produce distinctive music that has charmed listeners for over a century.

The Nutcracker

The short story on which The Nutcracker was based required a great deal of alteration to become appropriate for the ballet stage. Indeed, the plot of The Nutcracker bears little resemblance to E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” (1816), which can be categorized as a horror story. In Hoffmann’s account, a young girl, Marie (Clara in the ballet version), is subjected to terrifying nighttime encounters with the seven-headed Mouse King, who repeatedly threatens her. The tortuous plot hinges on a curse that transforms characters into hideous creatures with giant heads, gaping smiles, and long white beards. At the end of the story, Marie breaks the curse by pledging her love to the toy nutcracker that was given to her at Christmas by her godfather, the mysterious inventor Drosselmeyer.

Petipa (following an earlier adaptation by Alexandre Dumas) stripped this narrative of its horror elements, thereby transforming it into a family-friendly story about Christmas magic. The first act takes place at the home of Clara Stahlbaum, where guests have assembled for a Christmas Eve celebration. Drosselmeyer provides wonderful gifts for all of the children, including a nutcracker, to which Clara immediately becomes attached. After the party, Clara returns to the parlor to visit her nutcracker, where she witnesses a ferocious battle between the nutcracker—grown to life size and revealed to be a prince—and the Mouse King. She intercedes on the nutcracker’s behalf and he emerges victorious.

In the second act, the Nutcracker Prince takes Clara to his kingdom, the Land of the Sweets, where she is welcomed and celebrated. The courtiers put on a show for her to demonstrate their gratitude, presenting a series of dances while she and the Prince sit upon thrones. At the end of the ballet, Clara returns to her home—awakening, perhaps, from a fantastic dream.

The Nutcracker was premiered as part of a double-bill at the Imperial Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg. The other item on the program was Tchaikovsky’s newest opera, Iolanta, making for a complete evening of entertainment lasting about three hours. The premiere was not a success. Critics lambasted the dancing, the choreography, the adaption of the story, the sharp contrast between the acts, the prominence of children onstage, and the neglect of the principal ballerina, who, as the Sugar Plum Fairy, does not dance until nearly the end.

The music, on the other hand, was well-received, and Tchaikovsky was quick to salvage his work by transforming it into an orchestral suite that could be performed on concert programs. It was in this form that The Nutcracker first became popular. The Nutcracker was not staged again as a ballet until 1919, and did not enter the regular repertoire until 1934. A 1944 production by the San Francisco Ballet introduced it to American audiences. The New York City Ballet began offering annual performances in 1954, and the tradition of staging The Nutcracker during the Christmas season soon began to take hold across the United States. Today, The Nutcracker attracts millions of patrons every year, and is responsible for a large portion of the ticket sales by American ballet companies.

We will be taking a look at Act II of The Nutcracker. We will begin with the opening scene, in which Clara and the Prince arrive in the Land of the Sweets. Then we will examine part of the “Grand Divertissement” (that’s “grand entertainment” in English) that is staged for their amusement.

Act II: Introduction

The timestamps for this listening guide correspond with the 2001 BBC Worldwide production of The Nutcracker.

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 54’42” | Introduction to Act II | Clara and the Prince are welcomed to the Land of the Sweets. |

| 1:03’37” | The Prince tells the story of his victory over the Mouse King; we hear music from Act I. | |

| 1:06’03” | The dancers for the “Grand Divertissement” are introduced to Clara and the Prince. | |

| 1:06’11” | Chocolate (Spanish dance) | The melody is introduced by the trumpet, while castanets are heard throughout. |

| 1:07’46” | Coffee (Arabian dance) | A chromatic melody, heard first in the violins and later in the double reeds, floats above a droning rhythmic ostinato punctuated by tambourine strikes. |

| 1:12’24” | Tea (Chinese dance) | This dance pairs a flute/piccolo melody with pizzicato strings and a simple ostinato in the bassoon. |

| 1:13’50” | Russian Trepak | The fast-paced Trepak, which usues the entire orchestra, grows in intensity before culminating in a raucous final chord. |

| 1:15’04” | End of listening guide. |

Tchaikovsky opens Act II with harp arpeggios and a sweeping, romantic melody in the violins. Sustained pitches in the brass create a sense of calm and repose. When Clara and the Prince arrive onstage, they use pantomime and facial expressions to indicate their wonder at beholding the magical kingdom, while the music intensifies in excitement with the addition of ascending flourishes in the flutes and piccolo. Magical sounds are created by violin harmonics (a technique by which the player lightly touches the string to produce a high, wispy sound) and celesta, a keyboard instrument that produces bell-like sounds when hammers strike resonant metal bars. Tchaikovsky associated this instrument, invented in Paris in 1886, with the Sugar Plum Fairy, and he was the first to use it in a major work.

The entrance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, who has been ruling the Land of the Sweets in the Prince’s absence, is marked by another special effect (flutter tongue) in the flutes. She proceeds to greet Clara and the Prince, as do the subjects of the court. Next, the Prince tells the story of his battle with the Mouse King. He cannot use words, of course, so he reenacts the conflict in pantomime. He is aided by the orchestra, which repeats music from the battle scene—music that the audience heard only twenty or thirty minutes before and will easily recognize.

There has been dancing throughout the procedures thus far, of course, but nothing that could be described as a formal dance number. One of the challenges faced by any scenarist in designing a ballet is coming up with excuses for carefully-choreographed dance numbers. Ballet audiences enjoy the drama, but they want to see some good solo and ensemble dancing, not just pantomime. Petipa solved this problem by crafting a “Grand Divertissement” in which a series of dances are performed for Clara and the Prince. This “show within a show” is ostensibly put on for the benefit of the couple, but is in fact directed at the audience in the theater.

The “Grand Divertissement” consists of a diverse collection of themed dances. The first three dances are named after foods appropriate to the Land of the Sweets: chocolate, coffee, and tea. For each of these, Tchaikovsky drew inspiration from the lands from which these foods came: Spain, Arabia, and China. These are followed by a Russian dance, the “Dance of the Reed Flutes,” and a dance known as “Mother Ginger and the Little Clowns.” We will focus our attention on the first four dances for the purpose of considering how Tchaikovsky approached the task of representing national identity in music.

Act II: Chocolate

The Spanish dance is vibrant and exciting. The melody is first heard on the trumpet—an instrument that is not necessarily associated with Spanish music, but which introduces a bright timbre and sets the number apart from what has come before. The harmonies are simple and repetitive, suggesting a sort of generic “folk” style. What really marks the music as “Spanish” is the use of castanets, which are heard nowhere else in the ballet. Castanets are a simple percussion instrument that consists of two concave pieces of wood. These are held in one hand and clapped together. Castanets are particularly associated with the Spanish tradition of flamenco, which encompasses unique forms of guitar playing, singing, and dancing. By prominently featuring castanets, Tchaikovsky clearly signalled to his audience that the music and dancing were meant to be Spanish.

But how successful was he in replicating the sounds of flamenco music? We might compare Tchaikovsky’s music to a performance by flamenco musicians of the folk song “El Vito,” which dates to the 16th century. This rendition is typical of Spanish music in several ways. It is in a minor mode, with the melody supported by characteristics harmonies. The guitar player executes dissonant strums. And the castanet player provides complex accompanying rhythms. The performance of flamenco most often incorporates dance as well, and there is a rich vocabulary of movements and rhythmic steps that accompany and express the music. Next to these examples, Tchaikovsky’s Spanish dance sounds comically cheerful and simplistic.

In this example, a guitarist and castanet player perform “El Vito.”

In this example, the guitarist is accompanied by hand clapping, singing, and the rhythmic footwork of the dancer.

Act II: Coffee

Next is the Arabian dance. This time, Tchaikovsky employs a variety of compositional techniques to signal to his listener that this is “Middle Eastern” music. The low strings play a repeating rhythmic ostinato that produces a hypnotic effect. The ostinato features the interval of an open fifth, which leaves the question of mode open: we could be in major or minor. The ostinato also eliminates the possibility of complex harmonies, for we are to dwell on the same partial chord for the entire piece. Over the top of this, we hear a modal violin melody that incorporates both the raised and lowered seventh scale degrees and is characterized by unusual rhythms and phrasing. The melody prominently features the interval of an augmented second, which is seldom heard in European music, and it is scattered with trills. The melody is bookended by a repeated motif from the clarinets and double reeds and punctuated by the jingle of a tambourine. Later, the melody is echoed in the oboe and the bassoon. A modal shift concludes the dance on a major harmony.

For an example of authentic Middle Eastern music, one can refer to the discussion of Turkish makam music in Chapter 8. Many of Tchaikovsky’s strategies for representing the Middle East in sound are indeed rooted in genuine practice. The tambourine, for example, features prominently in Persian and Turkish music. Likewise, Middle Eastern compositions use modes other than major and minor, and their melodies often feature augmented seconds. The trill is not an uncommon ornament in some instruments, such as the flute, and an ostinato sometimes provides a musical backdrop for improvisation. Finally, double reed instruments such as the sorna are native to the Middle East.

In short, Tchaikovsky captures the sound of Middle Eastern music with considerable success. The main differences between the genuine article and Tchaikovsky’s imitation are the different timbres of the instruments, the inauthentic complexity of Tchaikovsky’s orchestration, and the Western intonation of the orchestral players, who do not tune their pitches in the same way as members of a takht ensemble.

All the same, Tchaikovsky contributes to a musical stereotype that casts Middle Eastern music as static and hypnotic. While it can have these characteristics, it usually does not. Unfortunately, these have become the hallmarks of Western imitations, with the result that a rich music tradition is reduced to a handful of cliches.

Act II: Tea

Next up is the Chinese dance, representative of tea. Tchaikovsky again makes use of an ostinato—this time, a rapid oscillation between the first and fifth scale degrees by the bassoon player. Above this we hear a high melody in the flutes and piccolos, punctuated by pizzicato from the strings. As the music grows in intensity, clarinets provide an arpeggiated accompaniment while bells sparkle alongside the flutes.

For an example of authentic Chinese music, we need only look to the previous example in this chapter. Any listener will immediately note that the Tchaikovsky’s dance has little to do with actual Chinese music. His choice of flutes for the melody might bring to mind the bright timbres often favored in Chinese music, but the similarity ends there. The steady rhythm, choice of scale, texture, and repetitive form all suggest that he had never actually heard Chinese music at all—or at least had no interest in creating a faithful reproduction.

Creating a faithful reproduction, of course, was never Tchaikovsky’s goal in any of these cases. Whether or not he accurately reflected the music of the cultures he parodied was purely incidental. Tchaikovsky’s only task was to entertain the Moscow audience members that purchased tickets to see the ballet. His audience was Russian, and he knew that they enjoyed exotic escapism as part of their theatrical entertainment. They were not alone.

Exoticism—the use of stereotypes to portray other cultures as exciting or mysterious—has a long history in European music, and especially in music for the opera stage. European audiences of the 18th and 19th centuries were intrigued by the cultural practices of distant lands, and they had a limitless appetite for their representation in the arts. The East held particular fascination, such that the term orientalism has been coined to describe the stereotyped representation of Eastern cultures. Such representations, however, are seldom accurate or flattering. Instead, exoticism dehumanizes its subject so as to provide an escapist experience to the consumer. Europeans often perceived exoticized subjects as sexually licentious, primitive, and driven by their emotions—or, to put it another way, free from the strictures of society. In this way, exoticized subjects became an object of both adoration and loathing. They could give in to temptations that were denied to European viewers, but only because they were less than human.

All of this might seem a bit tangential to The Nutcracker, which, after all, tells a charming story set in an imagined candy land, but it is not. The ballet’s representations of exoticized others—whether Romani people of Spain, or Arabs, or Chinese—contributes to a centuries-long practice that can still dehumanize these people today. This is best exemplified by a current controversy surrounding the performance of Tchaikovsky’s Chinese dance, which usually relies on stereotyped costumes, makeup, and choreography that many people find offensive.

In 2017, yellowface.org was founded specifically to advocate for changes in how the Chinese dance is presented in productions of The Nutcracker. The organization encourages arts leaders to sign the “Final Bow for Yellowface” pledge, which is a commitment to end racist representations of the Chinese characters. It also provides resources for creating new costumes, makeup, and choreography for use in Nutcracker productions that reflect genuine Chinese cultural practices instead of racist stereotypes. The movement has gained support, but most productions—including that associated with this text—continue to present a stereotyped visual representation of Chinese culture alongside Tchaikovky’s musical one.

Act II: Trepak

The final selection from the “Grand Divertissement” that we will examine here is the Russian dance, or Trepak. This time, Tchaikovsky took a model closer to home, for this dance is based on local Russian and Ukrainian folk practices. Unsurprisingly, the Russian dance is Tchaikovsky’s best imitation of the “real thing.” Both his Russian dance and the authentic trepak are fast-paced and in duple meter, with a driving rhythm suited to high-energy dancing. We again hear the tambourine—now a symbol not of the Middle East but of native folk culture.

In this video, you can see the kind of folk dance that inspired Tchaikovsky’s Trepak.

Javanese Traditional, The Love Dance of Klana Sewandana

Like sung drama, danced drama can be found around the world. Some of the richest traditions hail from Southeast Asia, where one can find dozens of distinct varieties of danced storytelling. Our example belongs to the wayang wong tradition, which developed in the courts of central Java, an island that is now part of Indonesia. Although wayang wong is unique to this small region, many of its musical and dramatic elements can be found across Java and throughout Indonesia. The most important of these is gamelan music, which is played on pitched gongs and keyed metallophones (marimba and xylophone are Western examples of such instruments).

Indonesia as Kingdom and Colony

Indonesia’s performing arts traditions reflect its diverse cultural heritage. Civilization on the islands dates back thousands of years. Indonesia was at first ruled over by a series of Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms, but the arrival of Islam in the 15th century resulted in the gradual conversion of the population. Today, Indonesia is the largest Muslim nation in the world, although many inhabitants practice a form of the religion that contains traces of the region’s Hindu and Buddhist heritage.

Javanese music is well known in the West due to the island’s colonial history. Dutch traders began to visit the Indonesian islands in the 16th century. The profitability of trade led to an influx of Dutch settlers, who established a local government under the auspices of the United East India Company. When the company failed in 1800, the Dutch government formally annexed the Dutch East Indies—which included most of Java—as a colony. Under Dutch rule, indigenous courts were allowed to remain intact, but they were granted only ceremonial powers. While this denied Indonesians their political autonomy, it contributed to the flourishing of Indonesian art, which the Dutch encouraged. It also facilitated the spread of Javanese music and art to Europe.

During World War II, Indonesia was occupied by the Japanese, who drove out the Dutch in an attempt to claim the islands for themselves. At the conclusion of the war, the Indonesians proclaimed independence. The Netherlands attempted to reassert its claim to the territory by force, and a military conflict ensued. In 1949, however, facing intense pressure from other powers, the Dutch acknowledged Indonesia as an independent nation. The impact of Dutch colonialism on the spread of Javanese cultural products resonates into the present day, and gamelan music in particular can be heard throughout the world. Indeed, there are over one hundred gamelan ensembles in the United States alone.

Wayang Wong

The dance form we will explore here, wayang wong, developed during the colonial era and resulted from the conflict between indigenous and colonial powers. Wayang wong was created at the court of Hamengkubuwono I, the first Sultan of Yogyakarta. Hamengkubuwono was to inherit the throne of the Mataram Sultanate from his brother, Pakubuwono II, but instead led his followers in a civil war after Pakubuwono agreed to cooperate with the United East India Company. The war ended in 1755 with a treaty establishing courts at Yogyakarta and Surakarta. Although this was nominally a victory for Hamengkubuwono, the Dutch ultimately benefited by pitting the courts against one another over the next two centuries. All the same, Yogyakarta remained a stronghold of Javanese resistance, and today serves as the capital of an independent region of the same name.

Wayang wong was initially conceived of as a decadent three-day spectacle celebrating and affirming the power of the newly-established Yogyakarta court. Although the first performance required dozens of dancers and lasted from dawn to dusk on each of the days, it has persisted in scaled-down forms. The term wayang wong literally means “human wayang.” This is in deference to the principal form of Indonesian theater, wayang kulit, which uses shadow puppets to act out traditional epics to the accompaniment of music.

All forms of wayang tell stories that have a long history in Indonesian culture. The principal sources are two Indian epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Wayang performances also draw from the Panji stories, which concern the life of a legendary Javanese prince. Each of these epics is much too long and complex to be related in a single performance. Instead, wayang performers select individual stories, which they often elaborate in ways that add novelty without disrupting the traditional narrative. Indonesian audiences are already familiar with the stories, and they appreciate seeing the characters and events presented with originality.

Gamelan

Our example presents an excerpt from the Panji stories, which we will consider in greater detail below. Before that, however, we owe some attention to the music that accompanies wayang wong dance. The instruments used in gamelan music date back to at least the 8th century, although they did not acquire their present form until the 15th or 16th century, when gamelan music became an important component of court life. Gamelan music is ubiquitous in traditional Indonesian culture. It can be performed on its own, but it is also used to accompany dance and theater. It is played for court celebrations and religious ceremonies, pursued by amateurs for their own enjoyment, and consumed by fans as entertainment.

A gamelan is a collection of bronze percussion instruments that are struck using a variety of mallets. The components of a gamelan include vertically-hung gongs of various sizes, smaller gongs suspended horizontally in wooden frames, and melodic instruments consisting of metal bars suspended over resonating chambers. The instruments of a gamelan are built together and they remain together. It is not possible for players to bring their own instruments, or for an instrument to be substituted. This is because there is no fixed pitch system in Indonesian music, so gamelan instruments are tuned to one another by the original builder. Every gamelan therefore plays a distinct set of pitches.

In addition to being communally stored and maintained, gamelans are bestowed with names. This not only recognizes the gamelan’s status as a complete ensemble but also signifies the traditional belief that a gamelan possesses a spirit. This spirit resides primarily in the largest suspended gong, the gong ageng, which might be provided offerings of food, flowers, and incense. The blacksmith who forges the bronze components of the gamelan instruments is traditionally understood to hold special powers, and he is expected to prepare for his task through fasting and self-purification. His carefully-tuned gongs and bars are then set in ornately-carved wooden frames.

Each instrument in a gamelan occupies a specific place in the musical texture. The vertically- and horizontally-suspended gongs are all used to mark the pulses of the rhythmic cycles that underlie gamelan music. These cycles, each of which is named, consist of patterns of timbres provided by the various gongs. The gong ageng always marks the end of the cycle, which repeats throughout a performance and provides the structure.

The other bronze instruments—which include two sizes of bonang, gendèr, slenthem (an instrument that resembles the gendèr but is pitched lower and has fewer keys), and two sizes of saron—play the same melody in heterophonic texture. However, each of these instruments interprets the melody in a markedly different way. Some play ornate versions, some play spare versions, and some play syncopated versions. The result is a complex texture woven out of the brilliant and resonant timbres of the many instruments.

Gamelan music also uses a few additional instruments, although these are not part of the main gamelan ensemble. Such instruments usually provide improvised melodies that follow the contour of the main melody but are otherwise independent. The instruments that might fill this role include the rebab (a bowed fiddle related to the Chinese jinghu), the gambang (a wood-keyed xylophone), and the suling (a type of flute). Finally, a male choir or female soloist might sing, drawing their texts from a body of poems and riddles that belong to the gamelan tradition. These texts, however, are not associated with any particular musical composition. Instead, they might be heard in a variety of contexts.

A gamelan performance is led by the drummer, who plays three different sizes of a drum known as kendhang. The drummer starts and stops performances, but his most important task is to control the pace and to signal the dramatic shifts in tempo that are characteristic of gamelan music. During performance, the ensemble will periodically slow to half of its former tempo or accelerate to twice the tempo. This is accompanied by changes in how the melody is interpreted by each of the instruments, which will add notes at slow tempos in order to maintain a consistent texture.

The Love Dance of Klana Sewandana

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 32’14” | Sekartaji alone in the forest | A few of the metallophones play a slow, simple melody; the rebab and solo female singer improvise high melodies; a percussionist taps rhythms on a wooden box. |

| 35’12” | Klana Sewandana enters and attempts to seduce Sekartaji |

The music at first becomes faster and more rhythmically intense; this is followed by fluctuations in tempo and dynamic. |

| 36’08” | A male solo singer enters and the rhythm becomes more regular. | |

| 37’52” | Prince Panji arrives and fights Klana Sewandana | The brighter/louder metallophones reenter the texture. |

| 38’21” | The male choir enters and most of the instruments drop out. | |

| 39’06” | The rebab enters. | |

| 39’35” | The solo female singer joins the male choir. | |

| […] | Instruments and singers continue to leave and reenter the texture as the music fluctuates in intensity. | |

| 45’30” | Prince Panji and Sekartaji are reunited | The music slows in tempo, then accelerates. |

| 48’00” | The music slows in anticipation of the final note. |

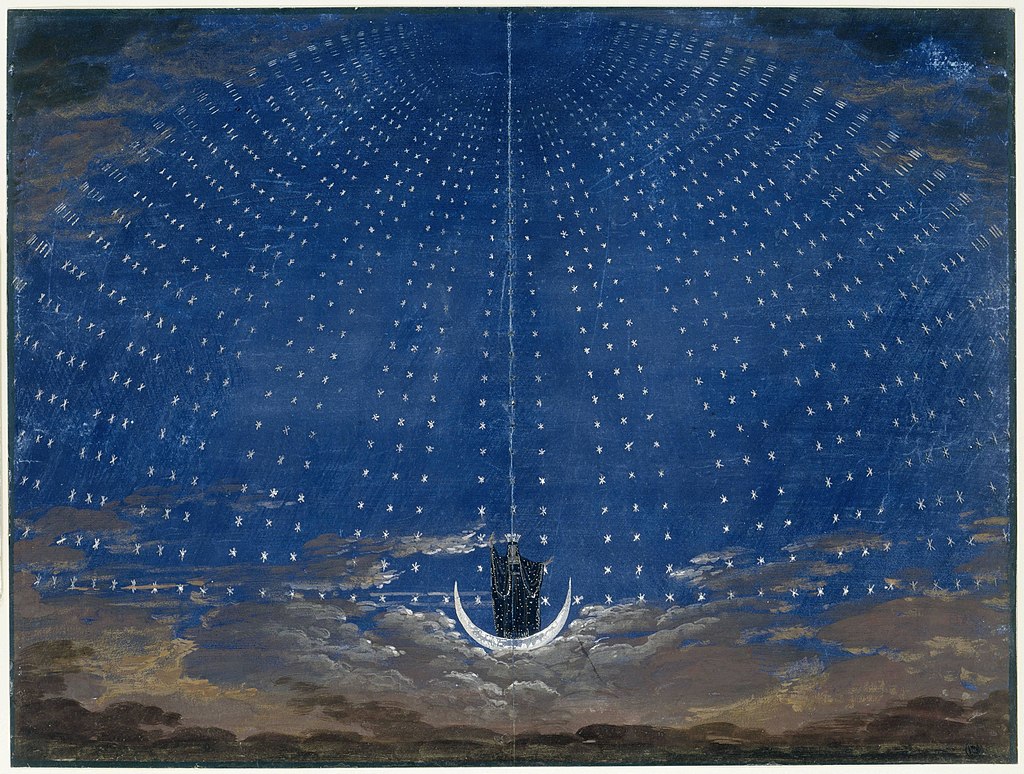

We are now prepared to turn to our example: A wayang wong performance that presents an episode from the Panji legends. Wayang wong is practiced both in masked and unmasked versions. This is obviously an example of the former. The use of masks in Indonesian dance dates back thousands of years. The masks are symbolically significant, and their shape, color, and details carry information about the character.

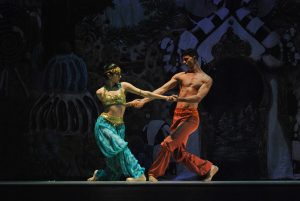

Many episodes of the Panji legend concern his romantic relationship with Sekartaji, who often finds herself separated from the Prince due to the intervention of malevolent forces. To survive, she frequently disguises herself as a man, at one point becoming the King of Bali and meeting Prince Panji on the battlefield. (There is also a long history of cross dressing in wayang dance itself.) The scene we will examine opens on Sekartaji alone in the forest. She has fled from the unwanted affections of King Klana Sewandana, whose obsession with her has driven him insane. Klana Sewandana attempts to seduce Sekartaji, but she rebuffs his advances. Luckily, Prince Panji has been drawn to the scene by his great love for Sekartaji. He fights and defeats Klana Sewandana, and the lovers are reunited.

The three dancers in the scene move differently, for they represent the three character types of wayang wong. As a female type, Sekartaji keeps her feet close to the ground while executing refined movements with her hands, neck, and head. Klana Sewandana is a strong male, as betrayed by his wide stance, large steps, and aggressive movements. Prince Panji, on the other hand, is a refined male. As such, he keeps his feet close to the ground and moves fluidly.

Throughout the episode, the gamelan provides a constant musical backdrop while accentuating the dramatic contour. Klana Sewandana’s arrival in the forest, for example, is marked by an intensification of the music, which grows in volume and increases in tempo. Musical outbursts punctuate the fight scene, while a musical calm descends on the final scene between Panji and Sekartaji. From time to time we hear the rebab, the suling, and various singers, who can be seen seated behind the dancers. The words they are singing have nothing in particular to do with the drama unfolding onstage, but voices contribute an important aesthetic element to any performance.

Resources for Further Learning

Brenner, Benjamin. Music in Central Java: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Church, Michael, ed. The Other Classical Musics: Fifteen Great Traditions. Boydell Press, 2015.

Lau, Frederick. Music in China: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Riley, Roland John. Tchaikovsky’s Ballets: Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, Nutcracker. Clarendon Press, 1985.

Romano, Renee and Claire Bond Potter, ed. Historians on Hamilton: How a Blockbuster Musical is Reshaping America’s Past. Rutgers University Press, 2018.

Whenham, John. Claudio Monteverdi: Orfeo. Cambridge University Press, 1986.