Unit 4: Music for Political Expression

9 National Identity

Esther M. Morgan-Ellis and Louis Hajosy

In a sense, all music is political. No form of musical expression is detached from issues of class, race, nationality, and identity. If we argue that a Mozart string quartet is free from all political concerns, we ignore the fact that Mozart lived and worked in Vienna, the powerful, German-speaking seat of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. We ignore the fact that 18th-century string quartets embodied Enlightenment-era political values regarding equality and rational discourse. And we ignore the fact that Mozart’s music is used today to represent elite cultural values.

In this chapter and the next, however, we will be exploring forms of musical expression that are explicitly political. We will examine a variety of musical works that were created to express or challenge political values. We will also encounter musical works that were not intended by their creators to contribute to political discourse, but that were coopted and repurposed by political actors.

In this chapter we will be considering the power of music to define and identify nations. The idea that music can express something important about a community has a long history. The ancient Greeks, for example, believed that the unique musical styles of each regional tribe represented the characteristics of that tribe. Moreover, they believed music to be so powerful that anyone who heard music from a particular tribe would in turn exhibit the characteristics of its members. Of course, for us to believe that music can express something about a group of people, we must first agree that all members of the group share something fundamental in common. This can be dangerous, for it invites the exclusion of any member who does not conform. Any claim that a piece or style of music represents a nation should be met with the question, “What members of the nation does this music fail to represent?”

National Anthems

The most explicitly political genre of music is the national anthem. Almost every country has one today, but national anthems have actually not been in use for very long. The first official national anthem was “God Save the Queen,” adopted by Great Britain in 1745. European countries began adopting anthems in the mid-19th century. This is the same period during which many modern European countries first came into existence, including Germany and Italy. This was also a period of growing nationalism. Artists, philosophers, and politicians generally agreed that people who shared an ethnic and linguistic heritage were somehow bound together and should belong to the same nation. Populations that shared such a heritage—the Hungarians, for example, who were governed by German speakers, or the Poles, who were governed by Russians—began to campaign for independence. Members of all ethnic groups generally agreed that art could express the characteristics of their people, whether or not they had secured autonomous rule. An official anthem became a means of documenting national values and expressing national pride.

National anthems can play an important role in shaping an individual’s relationship with the nation. To begin with, anthems are often sung in unison by large groups of people. Recent research has revealed that singing in a community increases levels of oxytocin, a hormone that is closely associated with interpersonal bonding. Singing together, therefore, actively promotes feelings of closeness and community solidarity. Group singing also causes participants’ breathing and heart rates to synchronize. Finally, studies have revealed that singing with other people promotes altruism, raises trust levels, and improves cooperation. It even raises pain thresholds. When groups of people sing the national anthem, therefore, they are not inspired only by the words or music. The experience of singing together itself reinforces national identity.

National anthems can also play a more abstract role in binding a nation together. The ritual of singing or hearing the anthem at sporting events and ceremonies helps us to feel connected with the nation and with one another. Whenever we sing or hear the anthem, we can imagine millions of our fellow citizens doing the same. We will never meet or even see the vast majority of these people, but the national anthem unites us, for it is the one song that everyone in the nation knows. That fact gives it great symbolic power.

Of course, the specific words and tunes of anthems are also of significance. It is difficult, however, to make generalizations about anthem texts and melodies, for there is a great deal of variety. To understand how the character and history of an anthem can reflect a nation’s identity, we will look at some examples.

United States of America: “The Star-Spangled Banner”

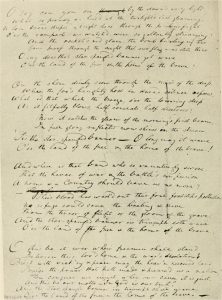

As is the case with almost every national anthem, the words and the tune to “The Star-Spangled Banner”1 were created by different people at different times. The tune is several decades older than the text, but our story will begin with the famous poem by Francis Scott Key (1779–1843). During the War of 1812, Key travelled with a delegation to the British flagship HMS Tonnant to negotiate a prisoner exchange. Although Key and his compatriots were successful in their mission, they were held captive after overhearing British officers plan an attack on the city of Baltimore. Key subsequently witnessed the nighttime battle from aboard a British ship. Famously, he knew that the American forces had emerged victorious when he saw their flag flying over Fort McHenry in the morning light on September 14, 1814. Key began his poem onboard the ship and finished it shortly after his release from captivity. The text of its earliest surviving draft appears below, transcribed from his handwritten manuscript.

“The Star-Spangled Banner”

Composer: John Stafford Smith

Lyricist: Francis Scott Key

Performance: Whitney Houston with The Florida Orchestra, conducted by Jahja Ling (1991)

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O’er the ramparts we watch’d, were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket’s red glare, the bomb[s] bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there,

O say does that star[-]spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep,

Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream,

’Tis the star-spangled banner—O long may it wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore,

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion

A home and a Country should leave us no more?

Their blood has wash’d out their foul footstep’s pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

O thus be it ever when freemen shall stand

Between their lov’d home and the war’s desolation!

Blest with vict’ry and peace may the heav’n rescued land

Praise the power that hath made and preserv’d us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto—“In God is our trust,”

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Originally untitled, Key’s poem was first printed in Baltimore a few days later, probably on September 17, in a broadside entitled “Defence of Fort M’Henry.” Broadsides—single sheets of paper printed on one side only—were commonplace in larger cities during the 18th and 19th centuries. Their texts often dealt with topics of the day, and they frequently carried news of a recent scandal, accident, crime, or execution. Such texts could be written, typeset, printed, and distributed very quickly, so broadsides were an effective means of spreading information. More specifically, “Defence of Fort M’Henry” was printed as a broadside ballad, so in addition to providing a ballad text (Key’s poem, in this instance), it named the popular tune to which the text was to be sung. Because buyers already knew the currently popular tunes, they could immediately sing the new lyrics. (This type of songwriting differs greatly from the approach common today, in which a single person typically creates both the lyrics and the melody—or at least works with a songwriting partner who provides the missing half. Reusing another composer’s melody would not only seem to lack creativity but would probably result in a lawsuit.)

It is not clear that Key himself had any particular melody in mind when he wrote “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” or that he ever intended for it to be sung. However, he had written song texts before. Indeed, various lines and images included in his September 1814 poem first appeared in his 1805 song “When the Warrior Returns.” Perhaps for this reason, the 1814 poem had the same pattern of syllables and rhymes as Key’s previous effort, and therefore fit the same tune. In the “Defence of Fort M’Henry” broadside, between an introduction describing the fort’s bombardment and the poem’s text, there appears the indication “Tune—Anacreon in Heaven.” Pairing the text with this melody produces a ballad—a narrative, strophic song. A strophic song is one in which each stanza of text is sung to the same melody.

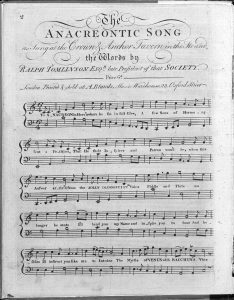

This tune, which we recognize today as the melody of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” was composed by John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) around 1776 and first published, with lyrics by Ralph Tomlinson (1744–78), as “The Anacreontic Song” around 1779. The song was also widely known as “To Anacreon in Heaven,” which are the opening words. Tomlinson’s lyrics celebrate the ancient Greek poet Anacreon, who wrote about love, wine, and amusements. Smith and Tomlinson created their song for the Anacreontic Society, a London gentlemen’s club founded around 1766. Its members were amateur musicians who desired to promote the arts and enjoy one another’s company. Their meetings included a concert, dinner, and light entertainment, and they sang “To Anacreon in Heaven,” the society’s “constitutional song,” after finishing their meal (the point at which the fun really began). Although the Anacreontic Society occasionally aspired to higher things, it was essentially a drinking club—and a rather lively one by all reports. The Society was shut down in 1792 after a visit by the Duchess of Devonshire provoked controversy over some lewd after-dinner songs. Though the Society had lasted for only a few decades, “To Anacreon in Heaven” was a hit. It quickly became popular with the creators of broadside ballads and accumulated a large number of texts. When “Defence of Fort M’Henry” appeared, therefore, the tune’s indication allowed any purchaser to immediately sing the ballad.

“The Star-Spangled Banner,” as it came to be known, joined a pantheon of patriotic 19th-century songs. It quickly gained popularity, but was generally overshadowed by “Hail, Columbia” and “America” (“My Country, ’Tis of Thee”). “The Star-Spangled Banner” faced significant criticism as a national song. The leading objection was that it was simply too difficult to sing. Indeed, its melodic range (an octave and a fifth) is unusually wide for a national anthem, and all but professional singers struggle to reach the highest notes. The melody is also characterised by disjunct motion—that is to say, the notes of the melody do not simply move up and down the scale, but instead are separated by large intervals. Others complained that its text, too specifically tied to a unique historical event, failed to reflect national values more generally. Finally, it has been criticized for its militaristic subject matter. All the same, the song slowly gained traction, first becoming popular at Independence Day celebrations. In 1899, the the US Navy adopted “The Star-Spangled Banner” for official use, and in 1916 President Woodrow Wilson ordered that it be played at all military events.

By the early 1900s, many variations of the song’s tune had arisen, so in 1917, President Wilson commissioned five prominent musicians—Walter Damrosch, Will Earheart, Arnold J. Gantvoort, Oscar Sonneck, and John Philip Sousa—to agree on and publish a standardized version. Baseball fans began singing the song at games beginning in 1918. Finally, on March 3, 1931, President Herbert Hoover signed a bill designating “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the national anthem of the United States. The legislation had been championed by Rep. John Linthicum of Baltimore, who, understandably, had taken an interest in promoting a local song. He was successful only following extensive debate over the song’s merits and deficiencies and the consideration of several alternatives, including “America the Beautiful.”

Performing “The Star-Spangled Banner”

There have been countless performances of “The Star-Spangled Banner:” most indifferent, but some exceptionally good or bad. It seems that a video of another “national anthem fail” circulates about once a year. But what is it that makes a “bad” performance? Sometimes, as in the case of Christina Aguilera’s performance at the 2011 Super Bowl, it’s because the singer forgets the words. Sometimes, as in the case of Victoria Zarlenga’s rendition at in international soccer match in 2012, it’s because the singer can’t stay on key. And sometimes, as in the case of Fergie’s performance at a 2018 NBA All-Star game, it’s because the singer takes an interpretive approach that is considered inappropriate (Fergie’s “sexy,” jazz-inspired version of the anthem provoked laughter and backlash).

So what makes a “good” performance”? These vary as well, but they usually share certain characteristics. First, of course, all of the notes and words are correct. Second, the accompaniment—if present at all—is in appropriate style; many successful renditions use military band instruments, which are conducive to patriotic expression. Third, the singing style needs to come across as dignified. This can mean several things. Singers with various backgrounds, including R & B, pop, rock, and opera, have all given successful performances. But the singer can’t sound like they’re showing off, and they can’t sound like they are trying to entertain. These unspoken rules can turn performing the national anthem into a nerve-wracking experience, for it is difficult to predict how audiences will interpret what they hear.

One of the most highly-praised renditions of the anthem was given by Whitney Houston at the 1991 Super Bowl. In examining her performance, we will consider how she blended her personal style with patriotic signifiers to satisfy the crowd.

Houston’s performance starts off with the sounds of the snare drum—a clear reference to marching music that simultaneously signifies the US military and captures the mood of disciplined patriotism that would attend a military review. The sound might also spark a sense of pride in the listener, or perhaps responsibility. It might make them stand up a little bit straighter. A trumpet fanfare precedes Houston’s entrance. When she does begin to sing, she is accompanied by a full brass ensemble, which underpins her lyrics with the power, volume, and brilliant timbre of a military band.

This orchestration remains consistent through the first A section of the musical form, but with the second A section (“Whose broad stripes. . .”) there is a significant change in the sound of the performance. Suddenly, Houston is backed by not a military band but soaring strings, whose shimmering timbre and connected articulation contrast with what we have just heard. And that’s not all: The strings also play harmonies that are significantly more adventurous and less predictable than those provided by the brass ensemble. The second A, therefore, is more meditative and introspective. It replaces an expression of military might with one of emotional complexity.

Houston emphasizes this contrast with her vocal production. She sings the first A section in a fairly straightforward manner, using the full power of her voice. In the second A section, however, she both reduces her volume and increases her use of ornamentation. Melodic ornaments, in this case, are any notes that are not included in the most basic version of “The Star-Spangled Banner”—the version you might sing at a sporting event or patriotic celebration. You can also hear how Houston changes her vocal production. Her sound becomes breathy and subdued—the result, in some cases, of using head voice instead of chest voice.

The mood changes again when we arrive at the B section (“And the rockets…”). The brass and percussion rejoin the strings, while Houston abandons her airy timbre and gives us the full power of her voice. The orchestra is primarily there to accompany the singer, but every once in a while a brass fanfare emerges from the texture. The climax of the anthem is accentuated by both the singer and the orchestra. On the word “free,” Houston adds a melodic ornament that takes her to the highest note of the performance—an interval of a fourth above the top note in the official version. Then, when she arrives at “brave,” the orchestra plays an unexpected harmony that prolongs the final cadence. In other words, we have to wait a few extra seconds before it feels like the song is really over.

South Africa: “National Anthem of South Africa”

The story of “National Anthem of South Africa” is equally tortuous, although the narrative details—and the resulting anthem—reflect a different type of national strife. While Germany came into conflict with the world, the South African conflict was entirely internal, unfolding as a white ruling minority sought to disenfranchise the non-white majority. This conflict and its resolutions were captured in a trio of official and unofficial anthems.

“National Anthem of South Africa”

Composers: Enoch Mankayi Sontaga & Marthinus Lourens de Villiers

Lyricists: Enoch Mankayi Sontaga & C.J. Langenhoven

Performance: Ndlovu Youth Choir (2019)

The roots of modern South Africa are to be found in the 17th century, when Dutch colonists first settled on its shores. The descendants of these colonists, who both displaced and intermingled with the native Africans, speak a language known as Afrikaans that combines elements of Dutch and indigenous languages. In the early 19th century, British colonists displaced the Dutch, and South Africa became a part of the British Empire. In this way, English became an important language, and it has continued to be widely spoken even since South Africa gained independence in 1931.

In total, eleven official languages are spoken in South Africa: Afrikaans, English, and nine indigenous African languages. This, of course, creates problems for the selection of a national anthem. The language of the anthem will naturally reinforce the power and the prestige of the citizens who speak that language, while symbolically excluding those who speak other languages. Language, therefore, plays an important role in the history of South Africa’s national anthems—and in that of other polyglot nations.

The political parties that came to power upon South Africa’s independence from Great Britain represented the interests of the Afrikaner and English-speaking minorities. A decade of increasing tension between ethnic groups culminated in the 1948 election of the National Party, an Afrikaner ethnic nationalist party that instituted the policy of apartheid (the Afrikaans word for “separateness”). Apartheid was a form of white supremacist segregation whereby every South African citizen was legally classified as “white,” “black,” “colored,” or “Indian.” A citizen’s racial classification then determined where they were allowed to live and what jobs they were allowed to hold. Public spaces were segregated, with preference given to “white” South Africans, and non-whites had limited power to vote. In addition, interracial marriages and sexual relationships were prohibited.

The National Party also adopted a new national anthem. South Africa had been using “God Save the King/Queen,” a legacy of its colonial status, but a political desire to distance British influence resulted in the 1957 designation of “The Call of South Africa” (Afrikaans: “Die Stem van Suid-Afrika”) as the national anthem. The text to “The Call of South Africa” was a 1918 Afrikaans poem by C.J. Langenhoven. The musical setting was created three years later by Marthinus Lourens de Villiers. The poem reflects an Afrikaner perspective, and it celebrates ownership of the South African land—which was taken from the native inhabitants by colonizing forces. As a result, “The Call of South Africa” was and continues to be deeply offensive to many black South Africans.

At the same time that “The Call of South Africa” was gaining popularity among Afrikaners, black South Africans were coalescing around an alternative anthem. “Lord Bless Africa”5 (Xhosa: “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika”) began life as a Methodist hymn. The tune, first verse, and chorus were composed in 1897 by Enoch Mankayi Sontaga, a teacher at a mission school. Sontaga, who was of Xhosa descent, was influenced by the British hymn tradition, and he described “Lord Bless Africa” as a combination of European four-part harmony with a repetitive, African-style melody. It quickly gained popularity among church congregations, and in 1912 was adopted by the South African Native National Congress, a political party that advocated the rights of black South Africans. In 1927, “Lord Bless Africa” was published in an expanded version that included seven additional Xhosa-language verses by Samuel Mqhayi. During apartheid, the hymn—which was banned by the National Party—became a symbol for resistance to the racist policies of the government. Many considered it to be the true national anthem.

This video captures a performance of “Lord Bless Africa” by Paul Simon and the group Ladysmith Black Mambazo to close Simon’s 1987 African Concert.

Apartheid officially came to an end with a 1992 referendum, and the first open elections of the post-apartheid era, which took place in 1994, put the previously-banned African National Party into power. Nelson Mandela, who had played a leading role in negotiating the end of apartheid, became President. Mandela had been imprisoned by the National Party for his anti-government activities from 1964 until 1990. As President, however, he was committed to the principles of reconciliation and equality. For this reason, he declared that “The Call of South Africa” and “Lord Bless Africa” would both hold the status of national anthem, and for several years both songs were performed at state and sporting events.

Although symbolically significant, having dual anthems was logistically difficult. The combined performance took about five minutes, and the question about performance order was politically charged. In addition, the two languages represented by the anthems fell significantly short of reflecting the linguistic diversity of the South African populace.

In 1997, therefore, Mandela commissioned a new anthem. He required that it combine the two existing anthems, contain verses in a variety of language, expunge controversial references to colonialism, and emphasize national unity. He also insisted that it be no longer than one minute and forty-eight seconds in length.

The resulting “National Anthem of South Africa” is in two parts, the first taken from “Lord Bless Africa” and the second from “The Call of South Africa.” It includes two verses from “Lord Bless Africa.” The first half of the first verse is in Xhosa, while the second half is in Zulu. The second verse is in Sethoso. At this point, the anthem modulates to a new key and we hear the first four lines of “The Call,” sung in Afrikaans to the original melody. The final lines of the anthem, which are in English, contain a new text calling for the people of South Africa to come together in order to “live and strive for freedom.”

Performing “National Anthem of South Africa”

Our rendition comes from the Ndlovu Youth Choir. This ensemble was founded in 2009 as an after-school program for impoverished children in the rural village of Moutse. The goal of the organizers was to provide these young people with the same quality of music education that was available to affluent youth and to thereby give them a means with which to express themselves and find a meaningful path in life. In 2019, the choir won international fame by advancing to the final round of America’s Got Talent. Many performances of “National Anthem of South Africa” feature a vocal soloist singing in a popular style and an orchestral accompaniment including brass and percussion—that is to say, they are stylistically identical to the anthem performances we have already examined in this chapter. The Ndlovu Youth Choir, however, developed a unique arrangement of “National Anthem of South Africa” that exhibits various indigenous singing styles.

“National Anthem of South Africa” is certainly unusual. It contains two unrelated melodies in different keys and verses in five languages. All the same, it reflects the diversity of the nation and speaks to a troubled past. It provides a musical representation of a nation that has been fractured and reunited.

National Representation in Western Art Music

As we have already seen, anthems are only the most obvious and explicit example of national representation in music. There are many ways in which music can come to stand for a nation. Sometimes, composers or performers set out to capture national character in sound. They seek to develop an individual work or a broader style that is uniquely tied to their national identity. Other times, those in power identify and promote music that is determined to represent the nation. In such cases the music is not created with the nationalistic intent, but rather repurposed. Finally, we might differentiate between musical representations created by the people who belong to nations or ethnic groups versus those created by outsiders.

We are not talking here about exoticism, wherein an artist represents an ethnic group for the purpose of voyeuristic entertainment, but rather contributions to national style made from a foreign perspective.

Contesting the Representation of Hungary

We will begin by looking at two compositions for piano, each created by a Hungarian composer who sought to express his national identity in music. Both composers turned to Hungarian folk music for inspiration, but they disagreed about which Hungarian folk tradition best represented Hungarian identity. This type of disagreement has larger implications about who “counts” as a citizen and whose culture can be understood to represent the nation.

It is important to note that the political nation of Hungary did not exist when either of these pieces were composed. Instead, Hungary was ruled by German-speaking monarchs, first as a territory of the Austrian Empire and then as a subservient partner in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Modern Hungary first gained independence upon the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire following World War I. Throughout the 19th century, however, Hungarians sought greater autonomy by means of political protest and armed revolt. Efforts to represent Hungarian identity in the arts were part of a larger nationalist movement that had ties to the quest for independence.

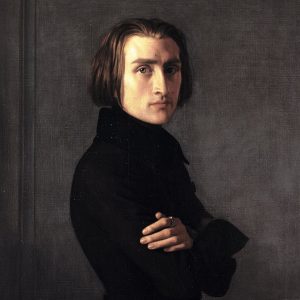

Franz Liszt, Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2

Franz Liszt (1811-1886) is an unusual candidate for “most famous Hungarian composer,” although he certainly merits the title. To begin with, he did not speak Hungarian. Although the village of Doborján in which Liszt was born was located in the Kingdom of Hungary, the inhabitants spoke German. Furthermore, Liszt lived in Hungary for only the first decade of his life. He demonstrated great musical talent as a child, so his parents took him to Vienna at the age of 11 to cultivate his gifts. He returned only on concert tours. All the same, Liszt was proud of his Hungarian heritage and expressed it frequently in his compositions for piano.

Liszt’s extraordinary career set new standards for piano playing and public performance. After a successful Viennese debut in 1822, he completed his education and embarked on what might have been a typical career of teaching, composing, and performing. In 1832, however, he happened to attend a recital in Paris by the Italian violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini. Liszt was astonished by Paganini’s extraordinary technique, and he committed to becoming Paganini’s equal at the piano. To this end, Liszt gave up concertizing and went into seclusion to refine his technique.

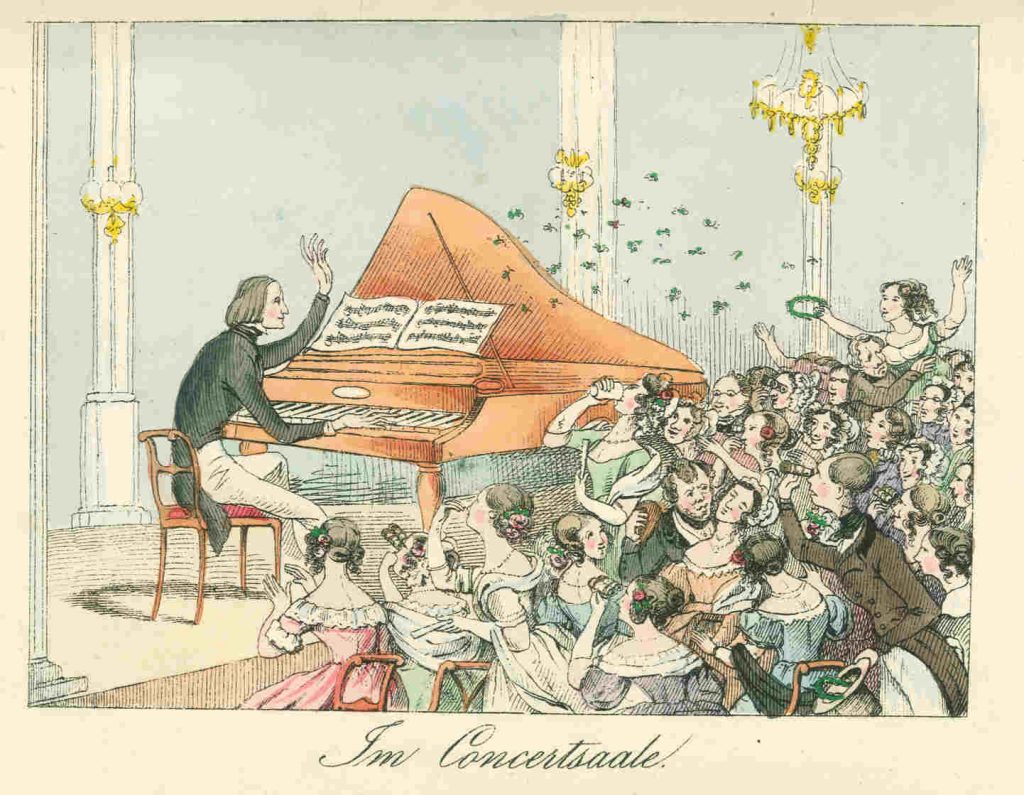

When Liszt returned to the stage in 1838, he was indeed heralded as the greatest living pianist. He embarked on a decade-long tour of Europe, during which he established a reputation for flamboyant and thrilling performances. It was Liszt’s practice to appear on stage with two pianos, for he played with such force that he would break strings and need to change instruments. Before Liszt, solo recitals were practically unheard of. Audiences preferred variety, and it was considered foolish to imagine that anyone would attend a concert with only one performer. Liszt, however, provided his own variety, combining piano transcriptions of symphonies with improvisations, classics by the great composers of the past, and showy new compositions by himself. Liszt also possessed a great deal of sex appeal. He was particularly popular with society ladies, who went into hysterics at his concerts and fought over his discarded items. Due to his enormous success, Liszt became the first performing artist to require a manager.

Liszt composed piano music in a variety of genres. His fantasies explored operatic themes written by other composers, while his etudes showcased specific piano techniques. He also produced nineteen Hungarian Rhapsodies, each of which was inspired by the Romani music that Liszt heard as a child. Liszt was not the first composer to write “Hungarian” music, which had been in fashion for decades. However, his Hungarian compositions were more personal than those of German composers, who used Hungarian musical elements to flavor their works. Liszt made it clear that his music was a personal statement that reflected his national identity.

We will examine Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, which is certainly his best-known effort in the genre. In it, Liszt uses the scales, rhythms, and forms of Hungarian music as a vehicle for dazzling piano technique. A good performance of Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 is entertaining and astonishing. Before looking at Liszt’s composition, however, we need to know something about the folk tradition on which the piece is based.

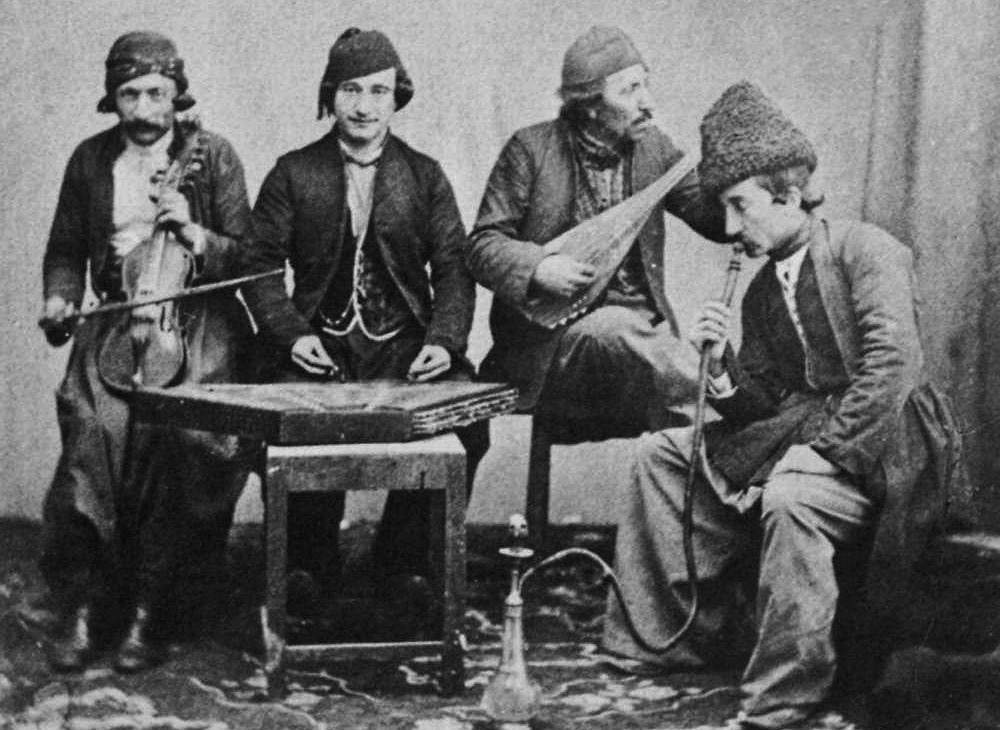

Liszt was influenced by a style of dance music known as verbunkos that he associated with the itinerant Romani musicians of his childhood home. The Romani—known colloquially as Gypsies—live across Europe, although they are often excluded from mainstream society and actively persecuted. In the village where Liszt grew up, Romani musicians played verbunkos music in cafes as entertainment for the upper classes. Their traditional instruments included violin and cimbalon, a type of hammered dulcimer. Although verbunkos music is unique to Hungary, therefore, it is closely associated with the Romani people, who are not ethnic Hungarians.

Verbunkos music has a variety of distinctive characteristics. To begin with, it is divided into two sections: an opening lassan and a concluding friska. The lassan is slow and melancholic, featuring dramatic harmonic shifts. It lacks a pulse and has an improvisatory feel. The friska, on the other hand, builds in volume and tempo, becoming increasingly exciting as it approaches a conclusion. The harmonies are simple, alternating between the tonic and dominant chords.

Verbunkos music also employs different scales than European concert music. While 19th-century composers of art music used only the major and minor scales, Romani musicians used various scales—mostly related to minor—that featured raised or lowered pitches and, as a result, contained augmented intervals (that is to say, intervals greater than a whole step, which is the largest possible distance between two notes in a major or minor scale). Such scales sounded exotic to Liszt’s audience, as they still do to many Westerners today.

Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 exhibits the influence of verbunkos dance music in a variety of ways. To begin with, it takes the two-part form of a lassan and friska. The lassan, which is exceptionally dramatic, features a march-like theme that is occasionally interrupted by unmetered flights of fancy. The music sounds as if it might be improvised, but in fact Liszt wrote out every note. In addition to these rhythmic characteristics, Liszt occasionally introduces unusual scales that echo Romani practice. The friska begins with a passage that is meant to imitate the sound of a Hungarian cimbalom. From there, Liszt finds his way to the major mode and provides a virtuosic conclusion.

| Time | Form | What to listen for |

| 0’00” | A | This introductory passage is dramatic and mysterious. |

| Lassan | This part of the rhapsody is characterized by unexpected harmonies and flexible tempos. | |

| 0’44” | B | The tempo stabilizes into a slow march. |

| 1’27” | C | This theme begins in the major mode. |

| 1’44” | D | This theme imitates the sound of a cimbalom; it accelerates in tempo. |

| 2’30” | A | |

| 3’04” | B | This theme returns in the low register of the piano. |

| 3’41” | C | |

| 4’36” | A | This theme returns in the lowest register of the piano. |

| Friska | This part of the rhapsody is characterized by stable harmonies and fast tempos | |

| 5’12” | D | This theme returns in the high register of the piano; as is accelerates in tempo, the harmony stabilizes. |

| 6’00” | E | This passage includes a large number of closely related themes; all are accompanied by the same harmonic pattern, which oscilates between the I and V chords. |

| 8’45” | The tempo slows and the melody briefly turns to the minor mode. | |

| 9’02” | The major mode returns, the tempo accelerates, and the volume builds, leading into an explosive final cadence. |

Béla Bartók, Romanian Folk Dances from Hungary

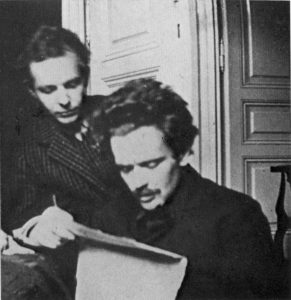

By the time Béla Bartók (1881-1945) was growing up in southern Hungary, Liszt was a national hero. Hungarians were proud of his monumental success across Europe and his influence on the elite musical establishment. They had also come to accept his musical representations of Hungarian identity—such as we observed in Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2—as authentic and correct. As a music student, therefore, Bartók took Liszt as a model and sought to express his Hungarian identity using a similar musical language.

Romanian Folk Dances from Hungary

Composer: Béla Bartók

Performance: Béla Bartók, Welte piano roll (1927)

In 1904, however, Bartók had an experience that changed his thinking about how Hungarian identity should be represented in art music. While visiting a summer resort, he happened to hear a nanny sing folk songs from the region of Transylvania. It was unlike any music he had ever heard before—and was certainly far removed from the verbunkos dance music of the urban cafes. He immediately set out to discover and document as much Eastern European folk music as he could find, becoming in the process one of the earliest ethnomusicologists (a scholar who specializes in indigenous music traditions).

Bartók found a like mind in fellow composer Zoltán Kodály, with whom he travelled the countryside recording the music of rural singers and instrumentalists. They sometimes used a primitive recording device that captured sound by carving grooves into a wax cylinder, but they also wrote down melodies using Western staff notation and they transcribed song texts. In 1906, they published Hungarian Folk Songs, a collection of peasant songs with simple piano accompaniments. Their intent was to spread awareness about the existence of the music, which they valued highly.

Following his studies, Bartók began to criticize Liszt’s version of Hungarian musical identity. Verbunkos dance music, he argued, was not the real Hungarian folk music. His objection was less to the ethnic identity of the Romani musicians who performed it as to the commercial context in which verbunkos music had developed and thrived. It flourished in the cities and was sponsored by the aristocracy as official Hungarian culture. True Hungarian folk music, argued Bartók, was to be found among the disenfranchised rural peasantry.

Bartók was interested both in promoting the cause of Hungarian independence and in developing his own unique voice as a composer. While he took genuine pride in the folk culture of Eastern Europe, he also saw it as grist for his own creative mill. His omnivorous appetite for folk music attracted some criticism from Hungarian nationalists. They were pleased when he promoted Hungarian folk music, but less supportive when he strayed beyond the bounds of the ethnic Hungarian population.

Again, however, we must ask, “Who counts as Hungarian?” This is not a question of literal citizenship, but a question of belonging. Which ethnic groups are to have their cultural products privileged as representing the nation? The borders of the Austro-Hungarian empire extended far beyond those of modern Hungary, encompassing a variety of ethnic groups and spoken languages. Bartók was not interested in deciding who counted as Hungarian. His mission was to collect and popularise as broad a selection of folk music as possible and to integrate that music into his own compositions.

To see one of Bartók’s compositional techniques in action, we will take a look at his Romanian Folk Dances from Hungary. It features tunes that he collected from the region of Transylvania, which was a part of Hungary for the first two decades of the 20th century. (Bartók shortened the title to Romanian Folk Dances when Romania annexed the region following World War I.) Like Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, this is a piece for solo piano based on Hungarian folk music. The similarities end there, however, for the purpose behind Bartók’s composition was completely different.

Romanian Folk Dances contains six independent movements. They are entitled “Joculcu bâtă” (Stick Dance), “Brâul” (Sash Dance), “Pe loc” (In One Spot), “Buciumeana” (Dance from Bucsum), “Poarga Românească” (Romanian Polka), and “Mărunțel” (Fast Dance). The melody of each movement is taken from a Transylvanian fiddle tune. Bartók did not alter the melodies, transcribing them as he had heard them. He then supplied an original accompaniment, which is usually heard in the left hand of the piano. Bartók described this approach as similar to crafting a piece of jewelry in order to show off a beautiful gem. His musical settings were supposed to exhibit the inherent beauty and interest of the folk tunes. All the same, his unusual harmonies are what make these pieces enjoyable and interesting for most listeners.

Because Bartók was unwilling to make changes to the borrowed folk tunes, each movement is short and simple in terms of form. Although only the second movement repeats literally in its entirety, all of the movements contain some melodic repetition. As in the Liszt example, we hear unusual scales and rhythms, which Bartók derived from the folk music he studied. Bartók, however, was not a virtuoso pianist, and he was not writing music for the purpose of popular entertainment. His emphasis was on fidelity to his source material, not show.

There are, of course, other reasons for which the music of Liszt and Bartók sounds quite different. Liszt was composing at the height of the Romantic era, when music was expected to be highly expressive while also adhering to certain rules about the use of harmony. Bartók, writing in the early 20th century, was a modernist. He sought to break new ground by replacing common-practice tonality—the typical chord progressions we are familiar with from most Western music—with a new harmonic language of his own invention. Romanian Folk Dances is an early example of his experimental work.

National Representation in Style and Instrumentation

In the previous section, we looked at four individual works that can each be understood to express something about national identity. All four of these works, however, belong generally to the tradition of Western art music. When Liszt and Bartók wrote for solo piano, they contributed to the repertoire for pianists trained in the classical style. When other composers composed symphonies, they adhered to norms developed by two centuries of European composers. In other cases, however, entirely new musical traditions come to represent a nation’s identity. Such traditions have unique characteristics and practices, and sometimes unique instruments as well. They become inextricably linked with national identity on an international level and can serve to further the political interests of a nation. Such is the case with the tradition of steelband music, which developed in and came to represent the nation of Trinidad and Tobago.

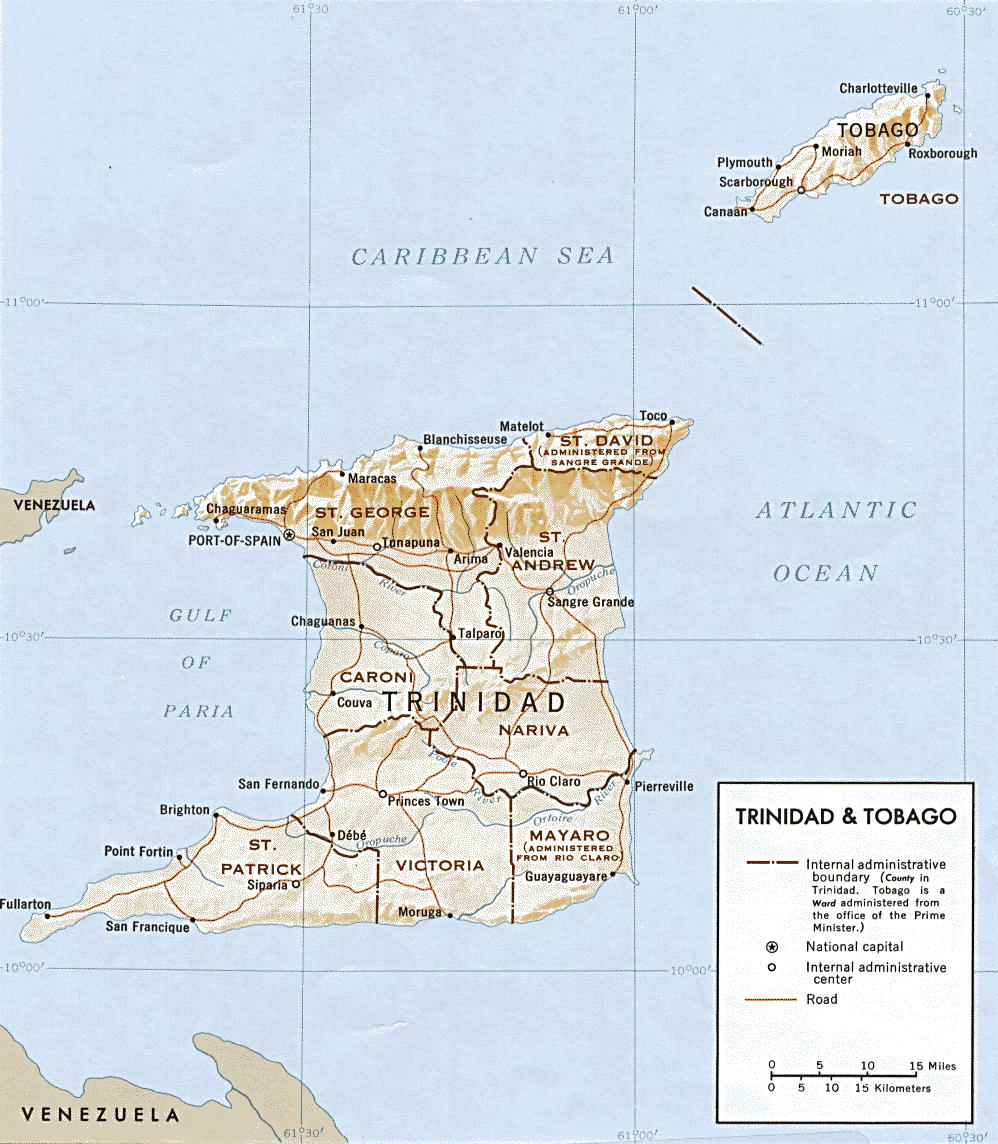

Steelband Music of Trinidad and Tobago

Like South Africa, the nation of Trinidad and Tobago is largely defined by its colonial past. The modern nation consists of two islands (Trinidad is the larger, Tobago the smaller). These islands were first claimed as a Spanish colony in 1498. The invaders rewrote the demographics of the region, essentially eradicating the indigenous population while bringing vast numbers of enslaved Africans overseas to work in the agricultural sector. For this reason, citizens of African descent now make up about 40% of the population.

By the end of the 18th century, Spain struggled to supply enough settlers to oversee its island’s industries. To this end, in 1783 the Spanish King invited French settlers to take over agricultural lands on the islands, resulting in French cultural influence. In 1797, however, the British took military control of Trinidad and Tobago, and the islands remained part of the British empire until independence in 1962.

As a result of British colonialism, English is the official language of Trinidad and Tobago, although most residents speak a creolized form that reflects the influence of several African languages. However, citizens of British descent make up only a small portion of the population. Following the abolition of slavery in 1838, Indian immigrants came to the islands as indentured laborers. Today, their descendants also make up about 40% of the population. Trinidad and Tobago, therefore, is a diverse nation in which African, Indian, and European influence can be discerned in everyday life.

The vestiges of Catholicism—brought centuries ago by Spanish and French colonists—will be central to our discussion. Although only a fifth of the nation’s population identify as Catholic today, one Catholic tradition in particular continues to have a major impact on the music of Trinidad and Tobago: Carnival. We discussed Carnival elsewhere in Chapter 4, for it played a significant role in the development of opera. Diverse Carnival traditions have arisen around the world in the wake of European imperialism. Although no two traditions are identical, all facilitate exuberant celebration in the period leading up to the start of Lent.

The history of Carnival in Trinidad and Tobago is tied to the history of the islands’ occupation. While Carnival was celebrated by the Spanish and French, it was suppressed by the British, who were not Catholic and did not approve of the celebration’s excesses. Under British rule, Carnival was restricted to the Monday and Tuesday before Lent. The islands’ governors, however, could not put down the celebrations altogether, and during the 19th century they became increasingly exuberant—sometimes even violent. The early 20th century saw Carnival transformed into a more respectable event. This was accomplished through the institution

of competitions for Carnival participants,

with perhaps the most coveted title—Calypso

Monarch—going to the performer of the best

new calypso song.

Music was always very important to Carnival. The calypso tradition developed among enslaved Africans, and has roots in the sung storytelling of West Africa. Here, however, we will focus on the dance music associated with Carnival—in particular, that performed on the nation’s indigenous instrument, the steelpan.

Steelpans developed out of an older tradition of dance music known as tamboo bamboo. Both traditions had something important in common: The instruments could be constructed at no cost out of readily available materials. Tamboo bamboo was performed using hollow bamboo sticks, which were stamped on the ground to create complex rhythmic patterns. The various dimensions of the sticks meant that they produced different tones. Tamboo bamboo developed after drums were banned by the British in 1834, but the practice was itself banned a century later as part of the ongoing attempt to quell the Carnival festivities.

Although the origins of steelpans—like those of most musical traditions developed by disenfranchised populations—are shrouded in mystery, it is certain that impoverished Afro-Trinidadian youth began building drums out of discarded biscuit tins in the late 1930s. The first experimenters entered into intense competition with one another, and each sought to create a drum that could play more individual pitches than that created by his rival. Notes could be produced by hammering raised bumps into the bottom of the tin, the size of which determined the pitch. Oil barrels, which were readily available due to the presence of a US naval base on the island, soon replaced biscuit tins as the material of choice. Before long, these musicians had developed drums that could play complete melodies—and were extremely noisy.

At first, the British government reacted to steelpans with the same disdain they had cast upon tamboo bamboo and drums in the past. There was general concern that the new instrument would fuel street violence and lead to civil unrest. In 1946, however, a steelpan musician named Winston “Spree” Simon played the British national anthem, “God Save the King,” for the governor. By performing a European melody on the instrument (and a patriotic one at that), Simon proved that steel pans could be respectable. The British immediately saw the instrument’s potential for the promotion of national pride and set about establishing the steelpan as a national instrument.

The process began in 1949, when a Government Steelband Committee was formed to promote steelpan music. The Committee in turn formed the Trinidad and Tobago Steelband Association and founded the Trinidad All Steel Percussion Orchestra. In 1952, a steelband category was added to the national Trinidad Music Festival, which had been established in 1948 to celebrate and encourage the European concert tradition. When steelbands participated in the Music Festival, they played European classics arranged for steelpans. Finally, in 1963, the Panorama competition was founded to celebrate the independence of Trinidad and Tobago. Panorama is a highlight of the annual Carnival celebrations, and it continues to honor the band who gives the best performance of a recent dance hit.

Over the first few decades of its existence, the steelpan became an extraordinarily flexible instrument. It had to be, seeing as it was used to play both nuanced symphonic classics and energetic dance music. An individual instrument has a full set of chromatic pitches (analogous to the keys on a keyboard) spanning at least one octave. Pans come in a variety of sizes, from the small tenor or lead pan to the bass pan, which requires multiple physical drums with just a few pitches each. A steelband will contain dozens of pans in a variety of sizes. The pans are played using rubber-tipped mallets, which are often “rolled” (repeatedly struck in a rapid pattern) on the instrument to create a sustained pitch.

Steelpan musicians have always valued their ability to play classical music. From the beginning, the performance of concert music demonstrated the sophistication of the instrument and the musicians—who at first were all members of the black community—in front of an international audience that was skeptical of their worth. In fact, the desire to play classical music well steered the development of the instrument, and many of its contemporary features, such as the suspension of the pans from metal frames, exist to facilitate concert performance. However, steelbands (or steel orchestras, as they are often called) don’t take on classical repertoire primarily to prove themselves. The musicians play concert music because they love it and because it is deeply meaningful to them.

Invaders: Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 5, Fourth Movement

Symphony No. 5, Movement IV

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

Performance: Invaders, World Steelband Music Festival (1992)

We will examine a performance from the 1992 World Steelband Music Festival, which developed out of the Trinidad Music Festival in 1964 (one year after Trinidad and Tobago gained independence). This festival celebrates the diverse capabilities of the instrument, for each competing band must perform both an arrangement of a calypso and a selection from the European concert repertoire. However, this structure has not been without conflict. In the years following independence, some representatives of the Afro-Trinidadian community insisted that steelbands should only play indigenous music, not that of the colonizers. Other factions were unwilling to sacrifice music they loved in order to make a political statement, and believed that European influence could make Afro-Trinidadian music better. These kinds of political concerns still preoccupy performers in the European tradition in all parts of the world.

In 1992, the Invaders chose the fourth movement of Bethoven’s Symphony No. 5 for their Festival performance. The Invaders are one of the oldest steelbands in Trinidad, tracing their lineage back to the earliest days of steelpan development. They have been equally successful performing concert repertoire and dance music, taking prizes at both the World Steelband Music Festival and Panorama.

For this performance, the Invaders add percussion instruments taken from the symphony orchestra, including a set of timpani. They dress in a manner that reflects concert hall practice (tuxedos for men, elegant matching jackets for women) and are led by a conductor. None of these elements would be present if the Invaders were competing at Panorama, but they are all considered appropriate for a performance of Beethoven. They do not read from sheet music, as orchestral musicians would, but have instead memorized their parts. The Invaders play all the notes just as Beethoven wrote them. The sound of the ensemble, however, is quite unlike anything Beethoven could have imagined.

Trinidad All Stars: Ultimate Rejects, “Full Extreme”

Our second performance, from the 2017 Panorama competition, it quite different. At Panorama, it is typical for a steelband to perform an arrangement of a hit song from the previous year. These arrangements are more than just transcriptions for steelband: That is to say, the members of the ensemble do not simply play the notes of the song on their instruments. Instead, steelband arrangers use the song as a starting point from which to craft elaborate variations. The resulting composition is usually about ten minutes long (in contrast to the three-minute popular song on which it is based) and demonstrate the full range of the ensemble’s capabilities.

Although steelbands used to perform arrangements of calypso songs, in recent years they have turned to a new genre of Carnival music: soca. Soca is a variety of electronic dance music. Unlike calypso, soca songs value danceability over lyric content. They are closely associated with Carnival, and often celebrate the spirit of freedom and joy that imbues the festivities. During Carnival, the new songs for that year are blasted from speakers carried through the streets on truck beds. Although recorded soca has largely displaced live steelband performances in Carnival parades, the musical practices continue not only to coexist but to influence one another.

In 2017, the Trinidad All Stars took first place in the Panorama competition with their arrangement of the soca song “Full Extreme,” which was released that same year by the band Ultimate Rejects. The song is characterized by its lively beat and repetitive melodic and textural refrains. The lyrics, which reflect a local English, dialect, celebrate the party spirit that cannot be quenched even by recession and disaster. The music video reinforces this message, as costumed carnivalgoers dance despite the oppressive presence of uniformed police. The refrain “We jammin still” captures the power of Carnival to overcome centuries of attempted repression.

This is the music video for the 2017 Ultimate Rejects song “Full Extreme.”

The extended performance of “Full Extreme” by the Trinidad All Stars fully captures the soca song’s energy, even though it includes no text. Central to the performance, of course, is the arrangement itself. Steelpan arrangers are highly regarded in the pan community, and the best are competitively recruited by the bands who hope to win Panorama. This 2017 arrangement of “Full Extreme” was created by Leon “Smooth” Edwards. Edwards was born in the capital of Trinidad and Tobago, Port of Spain, where he became involved with steelpan music at a young age. He played with the Trinidad All Stars from 1968 until 2002, continuing to participate in Carnival even after immigrating to the United States in 1988. Edwards began arranging in 1975, and won his first Panorama as an arranger in 1980. “Full Extreme” was his ninth win.

“Full Extreme”

Composer: Ultimate Rejects, arranged by Leon “Smooth” Edwards

Performance: Trinidad All Stars, Panorama Preliminary (2017)

In Edwards’ arrangement, you can hear the basic melodic elements of the Ultimate Rejects’ song. However, his arrangement is considered “good” because of the many ways in which it departs from the original, which is too repetitive to be very interesting in a purely instrumental version. In particular, Edwards makes use of the chromatic capabilities of the steelpan, writing passages that require players to strike almost every note on the instrument. He also contributes variations on the melody of the song. Finally, he occasionally interrupts the rhythmic groove, with has the effect of heightening the rhythmic excitement of his arrangement. The Trinidad All Stars’ performance is strong not only because they play all the correct notes at the correct times but because they exude energy throughout. The best steelpan players—like the best performers in many traditions—become physically involved in the music.

There are a number of additional noteworthy differences between the All Stars’ performance of “Full Extreme” and the Invaders’ performance of Beethoven. The players wear a coordinated uniform, but it is t-shirts, not tuxedos. They contains a drum set and various timekeeping instruments, not timpani. Before the performance begins, we can hear the succession of metallic strikes that set the music in motion. (Appropriately, the rhythm section in this type of steelband is referred to as the “engine room.”) The level of dedication and professionalism, however, is the same, as steelbands practice intensely—and in secret—in the months leading up to Carnival.

Resources for Further Learning

Beckerman, Michael B. New Worlds of Dvorák: Searching in America for the Composer’s Inner Life. W.W. Norton & Company, 2003.

Block, Adrienne Fried. Amy Beach, Passionate Victorian: The Life and Work of an American Composer, 1867-1944. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Dudley, Shannon. Carnival Music in Trinidad: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. Oxford University Press, 2003.

Ferris, Marc. Star-Spangled Banner: The Unlikely Story of America’s National Anthem. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014.

Hang, Xing. Encyclopedia of National Anthems. Scarecrow Press, 2003.

Riley, Matthew, and Anthony D. Smith. Nation and Classical Music: From Handel to Copland. Boydell Press, 2016.

Shadle, Douglas W. Orchestrating the Nation: The Nineteenth-Century American Symphonic Enterprise. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Taruskin, Richard. Music in the Nineteenth Century: The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Online

Patriotic Melodies Collection, Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/collections/patriotic-melodies/