7.5 Fake News

Erin Thomas, MFA

Argument vs. Opinion

Argument is often confused with opinion, and arguments and opinions may sound similar. Many times a person may think that they are asserting an argument when in reality they are voicing an opinion. When determining if something is an argument or opinion, consider two important differences:

- Arguments have rules; opinions do not. In other words, to form an argument, you must consider whether the argument is reasonable. Is it worth making? Is it valid? Is it sound? Do all of its parts fit together logically? Opinions, on the other hand, have no rules, and anyone asserting an opinion need not think it through for it to count as one; however, it will not count as an argument.

- Arguments have support; opinions do not. If you make a claim and then stop, as if the claim itself were enough to demonstrate its truthfulness, you have asserted an opinion only. An argument must be supported, and the support of an argument has its own rules. The support must also be reasonable, relevant, and sufficient.

Fake News

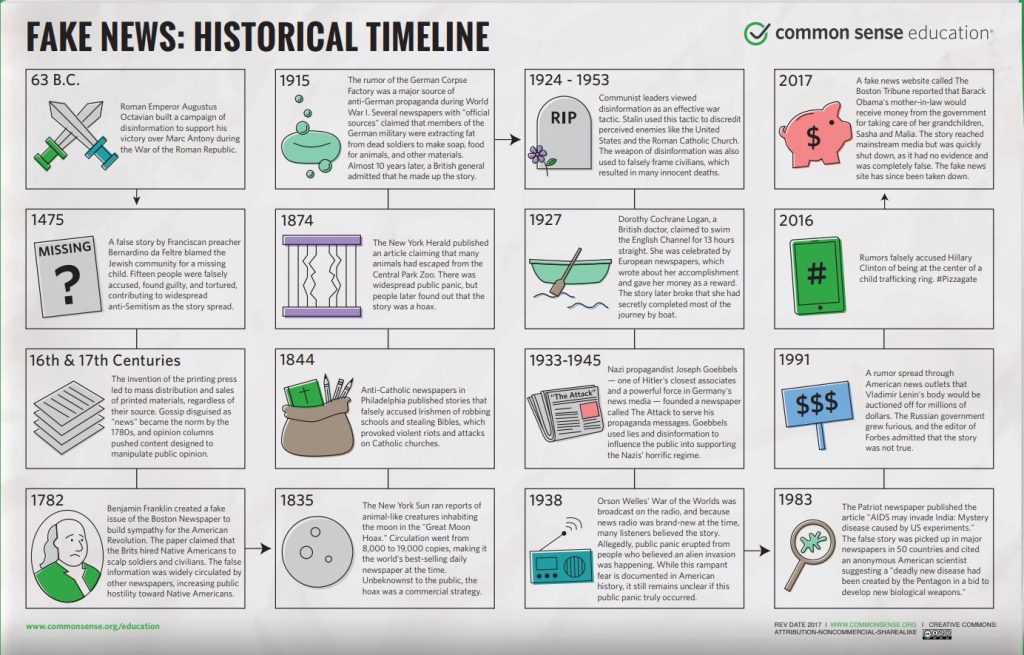

This term became particularly popular during the 2016 election, but misleading journalism is as old as the field of journalism itself. Consult the timeline below to see how fake news has impacted society throughout history. Just before the turn of the 20th century, Yellow Journalism was especially rampant in the U.S., which emphasized sensationalism over honest reporting. Currently, many popular news outlets and podcasters present opinions as facts, or purposefully mislead their audience with information that know to be false. For this reason, it’s essential to be able to tell the difference between an opinion and an argument, and information that is supported by research, and information that lacks evidence.

Although misleading information and reporting are prolific in our society, most Americans don’t feel confident in identifying it. Consider the following information from Statista:

- 26% of Americans are confident in their ability to recognize fake news

- 67% of Americans believe fake news causes “a great deal” of confusion

- 38.2% of Americans (self report) that they have accidently shared fake news[1]

Consequences of Fake News

War of the Worlds

The radio program, “The World of the Worlds” was first broadcast October 30, 1938, in New York. The author Orson Welles, based the broadcast on his novels by the same title. He neglected to begin the program by informing listeners that the content was fictional, and as a result, Americans across the U.S. believed they were under alien attack. This “unintentional” fake news demonstrated how fictional firsthand accounts/interviews and realistic sound effects could manipulate the public into irrational panic over irrational information. For an overview of the novel, consult the “War of the Worlds Overview” below.

Instructions

- Read the “War of the Worlds Overview.”

- Watch “Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News.”

- Watch portions of “Orson Welles – War of the Worlds – Radio Broadcast 1938″ to get an idea of how its original listeners felt.

- Read “The Corpse Factory Hoax” as an example of the damaging impacts of propaganda.

- And just for fun, read the Onion article: “CIA Realizes it’s Been Using Black Highlighters All These Years.”

- Consider the following questions:

- How confident are you in your ability to recognize fake news? Explain.

- When and where have you encountered fake news? How did you know it was fake news? Explain.

- If you had lived in 1938, do you think you would have believed the U.S. was being attacked by aliens? Explain.

- Based on your reading, of “The Corpse Factory Hoax,” why is propaganda dangerous? List two reasons suggested by the text. What are ways you can identify propaganda. Explain.

- Using the criteria you have learned in Chapter 7: Assessing Bias and Reliability to evaluate sources, explain how you can tell the article in the Onion is fake news.

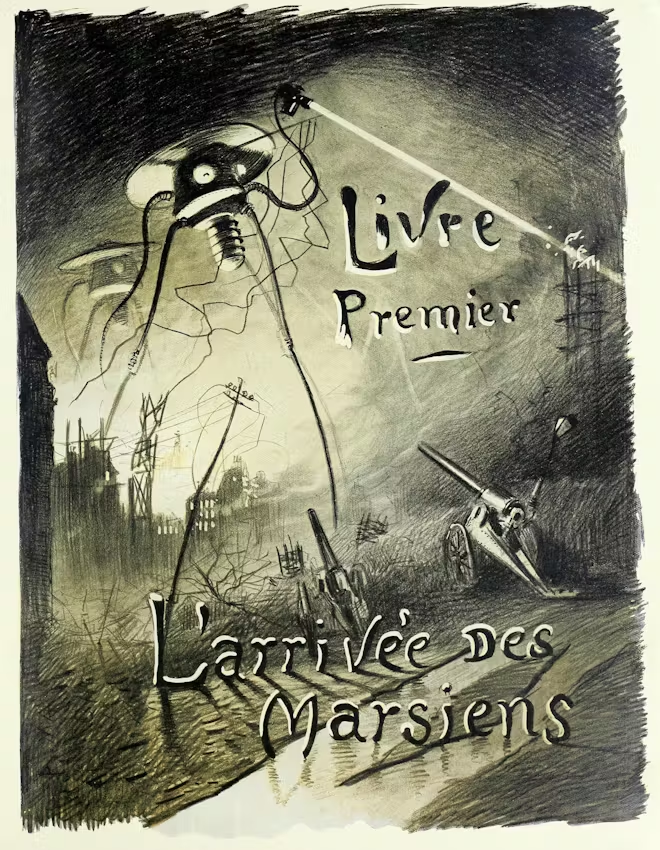

War of the Worlds Overview

Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.

— H. G. Wells (1898), The War of the Worlds

The War of the Worlds is a science fiction novel by English author H. G. Wells. It was written between 1895 and 1897,[2] and serialized in Pearson’s Magazine in the UK and Cosmopolitan magazine in the US in 1897. The War of the Worlds is one of the earliest stories to detail a conflict between humankind and an extraterrestrial race.[3] The novel is the first-person narrative of an unnamed protagonist in Surrey and his younger brother who escapes to Tillingham in Essex as London and Southern England are invaded by Martians because their world is becoming uninhabitable.

The novel is set in the mid-1980s in the summer. An object thought to be a meteor lands near the narrator’s home. It turns out to be an artificial cylinder launched towards Earth months earlier. Several Martians emerge from the cylinder and struggle with Earth’s gravity and atmosphere. When humans approach the cylinder waving a white flag, the Martians incinerate them using a heat ray. The crowd flees. That evening a large military force surrounds the cylinder.

The next night, the narrator sees a three-legged Martian “fighting-machine” (tripod), armed with a heat-ray and a chemical weapon. Tripods have wiped out the human soldiers around the cylinder and destroyed. The main character flees home to find that his landlord is dead, so he offers shelter to a lone soldier whose troop was wiped out, and they try to escape together. As refugees try to cross the River Wey, the army destroys a tripod with artillery fire, and the Martians retreat.

The Martians attack again, and people begin to flee London. The narrator’s brother reaches the coast and buys passage to Europe on a refugee ship. Tripods attack, but a torpedo ram, destroys two before being destroyed itself, and the evacuation fleet escapes. Soon, resistance collapses, and Martians roam the shattered landscape unhindered.

The plot is similar to other works of invasion literature from the same period and has been variously interpreted as a commentary on the theory of evolution, imperialism, and Victorian era fears, superstitions and prejudices. Wells later noted that inspiration for the plot was the catastrophic effect of European colonization on the Aboriginal Tasmanians. Some historians have argued that Wells wrote the book to encourage his readership to question the morality of imperialism.[4][5]

It is one of the most commented-on works in the science fiction canon.[6] The War of the Worlds has never been out of print: it spawned numerous feature films, radio dramas, a record album, comic book adaptations, television series, and sequels or parallel stories by other authors. It was dramatized in a 1938 radio program, directed and narrated by Orson Welles, that reportedly caused panic among listeners who did not know that the events were fictional.[7]

- Wells, H. G. (1898). The War of the Worlds. London: William Heinemann. p. iii – via S4U Languages. Facsimile of the original 1st edition.

- Hughes, David Y.; Geduld, Harry M. (1993). A Critical Edition of The War of the Worlds: H.G. Wells’s Scientific Romance. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-32853-5.

- Flynn, John L. (2005). War of the Worlds: From Wells to Spielberg. Galactic Books. ISBN 978-0-976-94000-5. OL 8589510M.

- Ball, Philip (18 July 2018). “What the War of the Worlds means now”. New Statesman. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Wills, Matthew (3 December 2018). “What The War of the Worlds Had to Do with Tasmania”. JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- Parrinder (2000), p. 132.

- Schwartz, A. Brad. “The Infamous “War of the Worlds” Radio Broadcast Was a Magnificent Fluke”. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

This page was last edited on 13 July 2025, at 15:41 (UTC).

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

For an explanation of how the War of the Worlds broadcast caused mass panic, watch the video below.

Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News

In order to get a better sense of what the listeners were experiencing, listen to a portion of the original broadcast using the link below.

Orson Welles – War of the Worlds – Radio Broadcast 1938

Propaganda

Propaganda is a powerful political tool, and we are more susceptible to fake news when it appeals to our biases, political positions, or fears. It’s important as an informed reader to steer clear of propaganda and political manipulation because most often the intention of this kind of misleading information is to mobilize countries, citizens, and factions against each other.

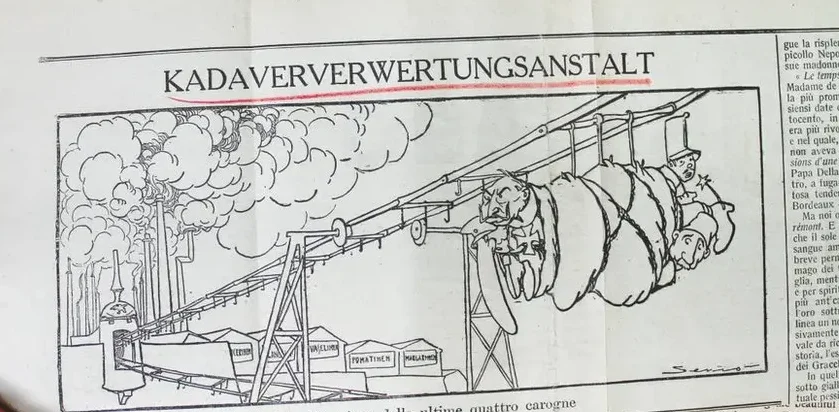

The Corpse Factory Hoax

A powerful example of propaganda is the “corpse factory” hoax. In 1917, Britain was desperate to engage China on the Allied side of WWI. The North China Daily News published the claim that the Kaiser’s armed forces were “extracting glycerin out of dead soldiers.” Rumors had already been circulating about factories that processed dead bodies for two years, so a news release that built upon already established suspicions was all-the-more credible. Later, British papers, eager to spur China to action, picked up the momentum. The Times and Daily Mail fabricated anonymous firsthand accounts of individuals who had actually visited the Kadaververwertungsanstalt corpse factory. The articles even quoted sources: a Belgian newspaper and the German Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger dated on April 10, 1917.

The German newspaper quoted a real German reporter named Kal Rosner, who was describing the noxious odor, “as if lime was being burnt,” from a factory that processed the corpses of horses and mules. “Kadaver,” the word used by Rosner, means animal bodies in German, not human bodies as “cadaver” means in English.

“Loathsome and ridiculous!” asserted the German government, but the Chinese ambassador was unconvinced and appalled by the supposed barbarity of using fallen soldiers as raw material for soap and margarine. Consequently, China declared war and joined the Allied forces against Germany on August 14, 1917.

Origins of the Hoax

For many years, it was unknown where the “corpse factory” hoax originated, but British intelligence likely had a hand in it. In 1925, Sir Austin Chamberlain admitted that there was “never any foundation” to the false news. The head of intelligence, MP John Charteris, admitted during a lecture tour in the U.S. that he had come up with the story. According to the New York Times, Charteris had combined two photographs: one of dead horses being prepared to be processed in a factory and another of a train of fallen soldiers being transported for burial. After combining the information from the photographs, Charteris sent the altered image to the North China Daily News in Beijing.

The British secret service, M17, paid writers during WWI to create articles for national papers. Major Hugh Pollard, a special correspondent for the Daily Express, secretly worked for M17. Following the conclusion of WWI, Pollard admitted to a cousin that his department at M17 had started the rumor and had written the accounts. The long-term impacts of this false news are chilling. During WWII, when Germany actually committed unbelievable acts of violence and brutality, the Nazis claimed it was just another tall tale fabricated by the British.

This article was adapted by Erin Thomas from: BBC News. (17 February, 2017). The corpse factory and the birth of fake news. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-38995205

Media Attributions

- Opinion-vs-Argument-full-graphic © Kalyca Schultz is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Fake News historical timeline © Common Sense Education is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- war of the worlds © Henrique Alvim Corrêa is licensed under a Public Domain license

- corpse factory © Leonard Raven-Hill is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Newspaper article

- Watson, Amy. (2023, July 14). Fake news in the U.S.-statistics & facts. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/3251/fake-news/#topicOverview ↵