7.4 Evaluating Pathos

Erin Thomas, MFA

Engaging Pathos

Literally translated, pathos means “suffering.” In this case, it refers to emotion, or more specifically, an appeal to the audience’s emotions. When writers establish an effective pathetic appeal, they make the audience care. If the audience does not care about the message, then they will not engage with the argument being made.

In 7.3 Evaluating Logos and Ethos, we discussed the importance of a political speech on social security using facts and figures to support the argument. However, to make this point more appealing to the audience, so that they will feel more emotionally connected to what the politician says, a story can enhance the impact. For example, Mary, an 80-year-old widow who relies on her Social Security benefits to supplement her income. The politician recounts visiting Mary the other day, sitting at her kitchen table and eating a piece of her delicious homemade apple pie. He explains how he held Mary’s delicate hand and promised that her benefits would be safe if she were elected. Ideally, the audience will feel sympathy or compassion for Mary because then they will feel more open to considering the politician’s views on Social Security (and maybe even other issues).

When evaluating a writer’s pathetic appeal, ask the following questions:

Does the writer try to engage or connect with the audience by making the subject matter relatable in some way?

- Does the writer have an interesting writing style?

- Does the writer use humor at any point?

- Does the writer use narration, such as storytelling or anecdotes, to add interest or to help humanize an issue within the text?

- Does the writer use descriptive or attention-grabbing details?

- Are there hypothetical examples that help the audience to imagine themselves in certain scenarios?

- Does the writer use any other examples in the text that might emotionally appeal to the audience?

- Are there any visual appeals to pathos, such as photographs or illustrations?

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Pathos:

Up to a certain point, an appeal to pathos can be a legitimate part of an argument. For example, a writer or speaker may begin with an anecdote showing the effect of a law on an individual. This anecdote is a way to gain an audience’s attention for an argument in which evidence and reason are used to present a case as to why the law should or should not be repealed or amended. In such a context, engaging the emotions, values, or beliefs of the audience is a legitimate and effective tool that makes the argument stronger.

An appropriate appeal to pathos is different from trying to unfairly play upon the audience’s feelings and emotions through fallacious, misleading, or excessively emotional appeals. Such a manipulative use of pathos may alienate the audience or cause them to “tune out.” Even if an appeal to pathos is not manipulative, such an appeal should complement rather than replace reason and evidence-based argument. In addition to making use of pathos, the author must establish her credibility (ethos) and must supply reasons and evidence (logos) in support of her position. An author who essentially replaces logos and ethos with pathos alone does not present a strong argument.

Developing Pathos through Figurative Language

Often writers use words and expressions in nonliteral ways to develop imagery or inspire pathos. Through this “figurative language,” writers describe characters, settings, and events. These words help create visual pictures and moods for the reader. Words used figuratively don’t always signify exact dictionary definitions, but make comparisons that help readers understand the emotional impact of a description more fully[1]. Much of the casual, idiomatic language used within a culture is figurative or symbolic. Consider the popular Gen Z term, “slay,” which means expertly complete a task or do something extremely well. This differs from the dictionary definition of slay, which is to kill something violently. It might be reasonable to suppose the popularity of gaming within Gen Z culture gave rise to this symbolic use of the word slay because succeeding in video games often includes killing game-zombies or other animated antagonists. Three other examples of Gen Z use of figurative language include the following:

- Glow Up: A improvement of appearance, confidence, or mental/physical health, which is derived from the term “healthy glow.”

- Flex: To show off or brag, which is derived from flexing muscles.

- Tea: juicy gossip, which refers to the old English custom of sitting down to afternoon tea to talk about the neighbors.

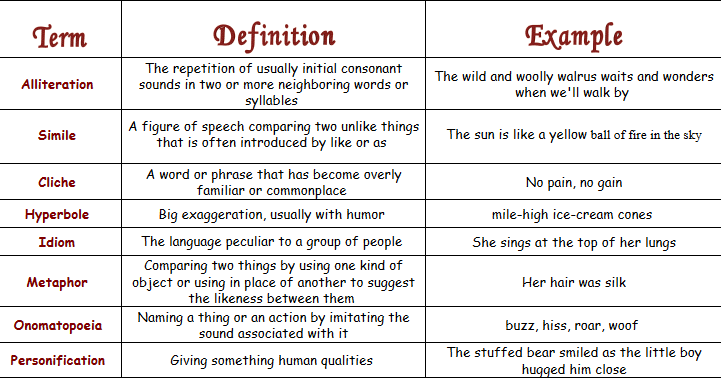

There are many types of figurative language, and the table below defines the most common ones. Students pursuing English degrees or a writing career may want to become more familiar with each category of figurative language; however, most of us shouldn’t worry if we can explain the exact difference between a metaphor and a simile. When developing pathos through figurative language, writers pay attention not only to the meaning of words, but the effect of the sound and pattern of words that they write. Therefore, you should focus on the following:

- Notice the general use of figurative language or description.

- Identify the overall emotional impact of this figurative language.

- Evaluate how a writer is using this language to impact or persuade you.

At times, you may be unfamiliar with the meaning of all the words that are being used or unsure of the exact emotion being elicited; in these cases, you can start by deciding if the language is positive or negative.

Political Arguments

Political arguments are unlike arguments made in an academic setting. While in an academic setting facts and statistics are highly valued, political arguments make extensive use of connotative, emotive, and manipulative language. While academic arguments attempt to persuade their audiences through their intellect, many political arguments attempt to persuade mostly through emotion, which typically results in less reliable and more biased arguments.

An academic argument is like a steak. All meat. It might have a little salt and a little pepper, but it’s served on a plain plate without much embellishment. It takes a lot time to eat a big steak. You have to cut off a small piece and chew it carefully to truly appreciate it. After eating a steak, you are full for several hours.

In contrast, a political argument is like a juicy hamburger. The patty might be full of fillers and artificial ingredients. Compared to the dressings, the meat part is small. You have a large bun made mostly of simple carbohydrates for instant energy. It’s topped with processed “American” cheese. It’s loaded with ketchup, mustard, greasy onions, lettuce, tomato, and pickles. A hamburger has instant crowd appeal, but so many fixings, it starts to slide apart; you have to grasp it with both hands to keep it together and sometimes the meat gets lost in all the toppings. An honest political argument will have a balanced mix of bun, meat, and dressings. An irresponsible political argument is all bun, little meat, and lots of sloppy extras … a pile of entirely too much mayonnaise to be appetizing in the long run.

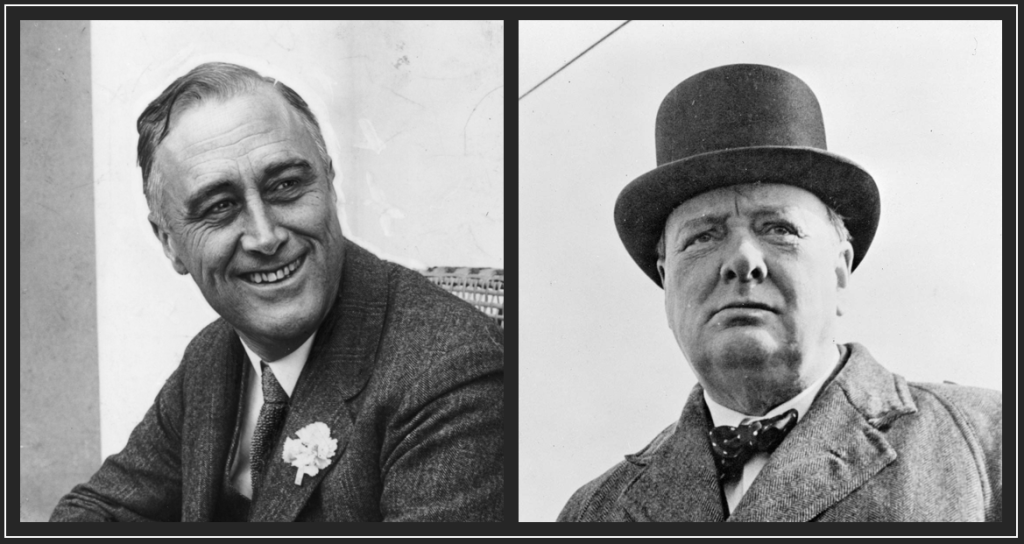

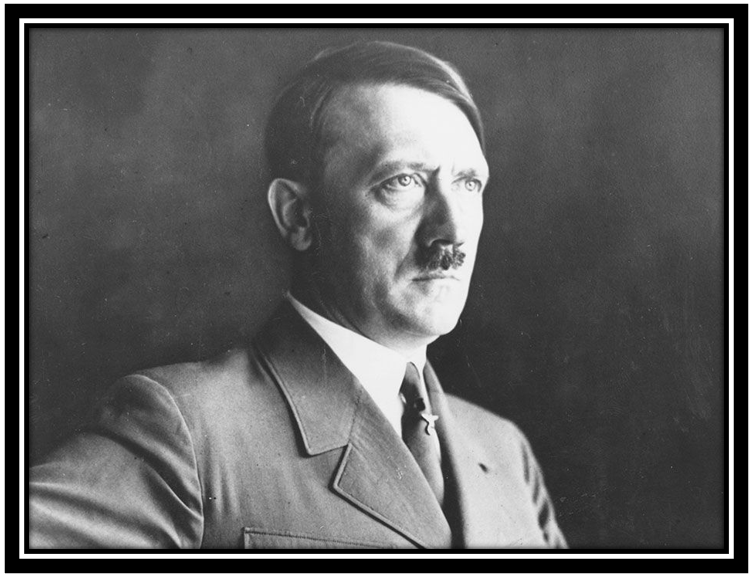

In a previous assignment, you read “A Hush over Europe” by former Prime Minister of England, Winston Churchill, and “The Good Neighbor Policy” by former President of the United States of America, Franklin D. Roosevelt. In this assignment, you will compare these two speeches with excerpts of some speeches by Adolf Hitler, Kaiser of Nazi Germany.

Instructions

- Both Churchill and Roosevelt were well-educated and known for their speaking skills. They led two democratic nations and used persuasive language, facts, and imagery to convince their audiences. In both “A Hush over Europe” and “The Good Neighbor Policy,” many of reasons that both speakers use as support for their arguments are verifiable facts. Other reasons are opinions, but they are opinions that may be held to be “true” by large groups of people. Both speakers made significant use of imagery and emotional language to persuade their target audiences. Select either “A Hush over Europe” or “The Good Neighbor Policy” and underline electronically/print to complete this exercise.

-

- Underline the verifiable facts in this argument.

- Draw a wavy line under the opinions.

- Circle emotive or connotative language and imagery.

- Answer the following question: Does this political argument have a good balance of the following qualities? Is it a responsible political argument? Explain your answer in at least 2-3 sentences.

- Before Adolf Hitler declared himself the supreme leader of Germany, he was a prime example of a demagogue. Consider this definition from Wikipedia:

Demagogue: a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, especially through oratory that whips up the passions of crowds, appealing to emotion by scapegoating out-groups, exaggerating dangers to stoke fears, lying for emotional effect, or other rhetoric that tends to drown out reasoned deliberation and encourage fanatical popularity. Demagogues overturn established norms of political conduct, or promise or threaten to do so. Type your textbox content here.

- In the years leading up to his domination over Germany, he prepared the minds of German people by appealing to fear and nationalism. By the time he delivered these excerpted speeches, he spoke plainly about his intentions for war. Most of the arguments he presents as “facts” in these excerpts would be considered as “opinions,” but unlike the assertions of Roosevelt and Churchill, these opinions would generally be rejected by civilized societies. Print or refer to the excerpts of Hitler’s speeches below to work by hand or electronically.

- Underline the verifiable facts in this argument.

- Draw a wavy line under the opinions.

- Circle emotive or connotative language and imagery.

- Answer the following question: Does this political argument have a good balance of the following qualities? Is it a responsible political argument? Explain your answer in at least 2-3 sentences.

-

ADOLF HITLER

Dictator of Germany from 1933 to 1945

Speech at Munich on March 15, 1929 to the German citizens (voters) and military

Killing is Essential to Survival

If men wish to live, then they are forced to kill others. The entire struggle for survival is a conquest of the means of existence, which in turn results in the elimination of others from these same sources of subsistence. As long as there are peoples on this earth, there will be nations against nations and they will be forced to protect their vital rights in the same way as the individual is forced to protect his rights. One is either the hammer or the anvil.

Militarization of Germany/Rejection of Peace Treaties

We confess that it is our purpose to prepare the German people again for the role of the hammer. We admit freely and openly that if our movement is victorious, we will be concerned day and night with the question of how to produce the armed forces, which are forbidden us by the peace treaty [Treaty of Versailles]. We solemnly confess that we consider everyone a scoundrel who does not try day and night to figure out a way to violate this treaty, for we have never recognized this treaty…We will take every step which strengthens our arms, which augments the number of our forces, and which increases the strength of our people. We confess further that we will dash anyone to pieces who should dare hinder us in this undertaking…Our rights will be protected only when the German Reich [country] is again supported by the point of the German dagger…

Speech at Nuremberg, September 14, 1935 at Hitler Youth Rally

Authoritarianism Equals Strength

Nothing is possible unless one will commands, a will which has to be obeyed by others, beginning at the top and ending only at the very bottom. This is the expression of an authoritarian state – not of a weak, babbling democracy – of an authoritarian state where everyone is proud to obey, because he knows: I will likewise be obeyed when I must take command.

Speech in Austria, April 9, 1938 German Voters

Germany’s conquest of Europe is Holy

To justify the annexation of Austria, Hitler called for a public vote on whether the unification should stand. This is an excerpt from a speech he gave on April 9, 1938, the day before the vote. As Hitler points out in his speech, he himself was born, and grew up, in Austria.

When one day we shall be no more, then the coming generations shall be able to look back with pride upon this day, the day on which a great Volk affirmed the German community. In the past, millions of German men shed their blood for this Reich. How merciful a fate to be allowed to create this Reich today without a suffering. Now, rise, German Volk, subscribe to it, hold it tightly in your hands! I wish to thank Him who allowed me to return to my homeland so that I could return it to my German Reich! May every German realize the importance of the hour tomorrow, assess it and then bow his head in reverence before the will of the Almighty who has wrought this miracle in all of us within these past few weeks.

Vocabulary:

- Volk: Folk. Hitler used this word to refer to the all Germans in the world

- Reich: Kingdom. This is the word Hitler used to refer to the country of Germany.

UNC Pembroke. (n.d.) Illuminating through inquiry. https://www.scribd.com/document/691110170/2b-Hitler-039-s-Speeches

Media Attributions

- figurative-language © Grace Richardson is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Cultivated_hamburger,_2013 © Mosa Meat is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Roosevelt and Churchill

- Hitler

- Richardson, G. (2019). The Reading Handbook. MHCC Library Press. https://open.ocolearnok.org/woscreadinghandbook/chapter/figurative-language/ ↵