7.3 Evaluating Logos and Ethos

Erin Thomas, MFA

Logic and Credentials

Using Logos

Literally translated, logos means “word.” In this case, it refers to information, or more specifically, the writer’s appeal to logic and reason. A successful logical appeal provides organized information as well as evidence to support the overall argument. If the writer fails to establish a logical appeal, then the argument will lack both sense and substance.

For example, consider the example of a political speech about social security benefits. How convincing would the argument be without providing any statistics, data, or concrete plans for how the politician proposed to protect Social Security benefits? Without any factual evidence for the proposed plan, an educated audience would be less likely to find it plausible.

When evaluating a writer’s logical appeal, ask the following questions:

Does the writer organize the information clearly?

- Ideas are connected by transition words and phrases

- Ideas have a clear and purposeful order

Does the writer provide evidence to back the claims?

- Specific examples

- Relevant source material

Does the writer use sources and data to back claims rather than base the argument purely on emotion or opinion?

- Does the writer use concrete facts and figures, statistics, dates/times, specific names/titles, graphs/charts/tables?

- Are the sources that the writer uses credible?

- Where do the sources come from? (Who wrote/published them?)

- When were the sources published?

- Are the sources well-known, respected, and/or peer-reviewed (if applicable) publications?

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Logos:

Pay particular attention to numbers, statistics, findings, and quotes used to support an argument. Be critical of the source and do your own investigation of the facts. Remember: What initially looks like a fact may not actually be one. Maybe you’ve heard or read that half of all marriages in America will end in divorce. It is so often discussed that we assume it must be true. Careful research will show that the original marriage study was flawed, and divorce rates in America have steadily declined since 1985 (Peck, 1993). If there is no scientific evidence, why do we continue to believe it? Part of the reason might be that it supports the common worry of the dissolution of the American family.

An Appeal to Ethos

Literally translated, ethos means “character.” In this case, it refers to the character of the writer or speaker, or more specifically, credibility. Writers need to establish credibility so that the audience will trust them and, thus, be more willing to engage with the argument. If writers fail to establish a sufficient ethical appeal, then the audience will not take the argument seriously.

For example, if someone writes an article that is published in an academic journal, in a reputable newspaper or magazine, or on a credible website, those places of publication already imply a certain level of credibility. If the article is about a scientific issue and the writer is a scientist or has certain academic or professional credentials that relate to the article’s subject, that also will lend credibility to the writer. Finally, if this writer demonstrates knowledge about the subject by providing clear explanations of points and by presenting information in an honest and straightforward way, this also helps establish credibility.

When evaluating a writer’s ethical appeal, ask the following questions:

Does the writer come across as reliable?

- Viewpoint is logically consistent throughout the text

- Does not use hyperbolic (exaggerated) language

- Has an even, objective tone (not malicious but also not sycophantic)

- Does not come across as subversive or manipulative

Does the writer come across as authoritative and knowledgeable?

- Explains concepts and ideas thoroughly

- Addresses any counter-arguments and successfully rebuts them

- Uses a sufficient number of relevant sources

- Shows an understanding of sources used

What kind of credentials or experience does the writer have?

- Look at byline or biographical info

- Identify any personal or professional experience mentioned in the text

- Where has this writer’s text been published?[1]

Instructions

- Read the excerpted “The Good Neighbor Policy,” a speech given by President Franklin D. Roosevelt stating America’s neutrality as tensions rose in Europe during 1936.

- Skim to get an overall idea about the topic of the text, consulting the section headings to understand how the argument progresses.

- Next, highlight or annotate the text as you read to identify the major supporting points of the argument.

- In order to understand more about Roosevelt’s “ethos,” you can search for more information about him on the Internet.

- Consider the following questions as you evaluate the ethos and logos of the argument.

-

- Who is the author?

- Does this author have experience or expertise on the topic of the text?

- What is the claim?

- What reasons does the author offer to support his claim?

- What types of evidence are used?

- Does the author offer sufficient evidence?

- Is the evidence convincing?

- What action is called for?

-

FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT

32nd President of the United States: 1933 ‐ 1945

Address at Chautauqua, N.Y.

August 14, 1936

On the same day that Joe Rantz and his crew won the Olympic Gold in Germany, President Frankline D. Roosevelt (FDR) spoke to a crowd in Chautauqua, New York about worsening international tensions surrounding the rise of Nazism and the militarization of Germany. The U.S. was still suffering from the Great Depression, but FDR indicated that he was more concerned about global conflict than the future of the U.S. economy. He expressed his desire to stay neutral should war break out in Europe. The following are excerpts of this speech delivered on August 14, 1936. This speech is now known as the “Good Neighbor Policy.”

Introduction of the Good Neighbor Policy

In the field of world policy I would dedicate this Nation to the policy of the good neighbor- the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others—the neighbor who respects his obligations and respects the sanctity of his agreements in and with a world of neighbors.

This declaration represents my purpose; but it represents more than a purpose, for it stands for a practice. To a measurable degree it has succeeded; the whole world now knows that the United States cherishes no predatory ambitions. We are strong; but less powerful Nations know that they need not fear our strength. We seek no conquest; we stand for peace.

In the whole of the Western Hemisphere our good-neighbor policy has produced results that are especially heartening.

Relationship with Canada

The noblest monument to peace and to neighborly economic and social friendship in all the world is not a monument in bronze or stone, but the boundary which unites the United States and Canada—3,000 miles of friendship with no barbed wire, no gun or soldier, and no passport on the whole frontier.

Mutual trust made that frontier. To extend the same sort of mutual trust throughout the Americas was our aim.

Relationship with Latin America and the Caribbean

We have negotiated a Pan-American convention embodying the principle of non-intervention. We have abandoned the Platt Amendment which gave us the right to intervene in the internal affairs of the Republic of Cuba. We have withdrawn American marines from Haiti. We have signed a new treaty which places our relations with Panama on a mutually satisfactory basis. We have undertaken a series of trade agreements with other American countries to our mutual commercial profit. At the request of two neighboring Republics, I hope to give assistance in the final settlement of the last serious boundary dispute between any of the American Nations.

Throughout the Americas the spirit of the good neighbor is a practical and living fact. The twenty-one American Republics are not only living together in friendship and in peace; they are united in the determination so to remain.

FDR’s hope for peace in Europe

Peace, like charity, begins at home; that is why we have begun at home. But peace in the Western world is not all that we seek.

It is our hope that knowledge of the practical application of the good-neighbor policy in this hemisphere will be borne home to our neighbors across the seas. For ourselves we are on good terms with them—terms in most cases of straightforward friendship, of peaceful understanding.

We are not isolationists except in so far as we seek to isolate ourselves completely from war. Yet we must remember that so long as war exists on earth there will be some danger that even the Nation which most ardently desires peace may be drawn into war.

FDR’s experience in WWI

I have seen war. I have seen war on land and sea. I have seen blood running from the wounded. I have seen men coughing out their gassed lungs. I have seen the dead in the mud. I have seen cities destroyed. I have seen two hundred limping, exhausted men come out of line—the survivors of a regiment of one thousand that went forward forty-eight hours before. I have seen children starving. I have seen the agony of mothers and wives. I hate war.

FDR’s commitment to stay neutral

I have passed unnumbered hours, I shall pass unnumbered hours, thinking and planning how war may be kept from this Nation.

I wish I could keep war from all Nations; but that is beyond my power. I can at least make certain that no act of the United States helps to produce or to promote war. I can at least make clear that the conscience of America revolts against war and that any Nation which provokes war forfeits the sympathy of the people of the United States.

Reasons for war

Many causes produce war. There are ancient hatreds, turbulent frontiers, the “legacy of old forgotten, far-off things, and battles long ago.” There are new-born fanaticisms, convictions on the part of certain peoples that they have become the unique depositories of ultimate truth and right.

A dark old world was devastated by wars between conflicting religions. A dark modern world faces wars between conflicting economic and political fanaticisms in which are intertwined race hatreds.

Choosing peace

Before this selection, FDR explained that war would bring profit to the U.S., but that peace was more important.

If we face the choice of profits or peace, the Nation will answer—must answer—”We choose peace.” It is the duty of all of us to encourage such a body of public opinion in this country that the answer will be clear and for all practical purposes unanimous … I have thought and worked long and hard on the problem of keeping the United States at peace. But all the wisdom of America is not to be found in the White House or in the Department of State; we need the meditation, the prayer, and the positive support of the people of America who go along with us in seeking peace.

We can keep out of war if those who watch and decide have a sufficiently detailed understanding of international affairs to make certain that the small decisions of each day do not lead toward war and if, at the same time, they possess the courage to say “no” to those who selfishly or unwisely would let us go to war.

Conclusion

Of all the Nations of the world today we are in many ways most singularly blessed. Our closest neighbors are good neighbors. If there are remoter Nations that wish us not good but ill, they know that we are strong; they know that we can and will defend ourselves and defend our neighborhood.

We seek to dominate no other Nation. We ask no territorial expansion. We oppose imperialism. We desire reduction in world armaments.

We believe in democracy; we believe in freedom; we believe in peace. We offer to every Nation of the world the handclasp of the good neighbor. Let those who wish our friendship look us in the eye and take our hand.[2]

Media Attributions

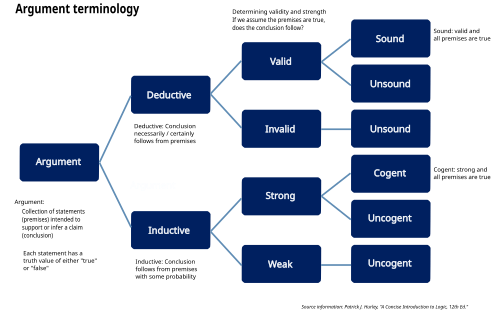

- Argument_terminology_used_in_logic_(en).svg © Nyq is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Browning, E., Boylan, K., Burton, K., DeVries, K., & Kurtz, J. (2018). Let's Get Writing. Virginia Western Educational Foundation, Inc. https://pressbooks.pub/vwcceng111/chapter/chapter-2-rhetorical-analysis/ ↵

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, Address at Chautauqua, N.Y. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/208921 ↵