6.6 Mapping the Argument

Erin Thomas, MFA

Bringing it Full Circle

So far in this text, we have completed several exercises on note-taking with lectures and textbook chapters. Now that we’ve reviewed the rhetorical structure of arguments in greater depth, you can take notes with more purpose.

For instance, it’s more important to take notes of certain kinds of evidence.

- Most often, descriptions are not included in chapter tests, while reasons often are.

- Sometimes examples are important details to record for tests, and other times they are mentioned simply as an illustration.

- Key facts and statistics are important to record, while it’s more important to remember the findings of a research study than how the study was conducted when citations of research are used as evidence.

Also, when you are representing the type of evidence used in your notes, you can identify examples with the expression: ex: Often, you will list reasons numerically under a topic heading: 1, 2, 3. And when you are noting key facts and statistics, it’s important to be exact and write these verbatim with numbers and percentages.

Therefore, a better understanding of types of evidence can help you decide what to remember and take notes on, in addition to helping you decide how you are going to take notes.

Understanding the rhetorical pattern of an argument helps you understand how the evidence connects. Often it’s difficult to get the right answer on a multiple choice test if you don’t understand what the pattern of argument is communicating about the evidence. Understanding a pattern of argument can also help you structure your notes.

- Often, definitions follow a specific term.

- Time process and sequence as well as cause-effect are often represented with arrows.

- Classification and comparison-contrast are well represented in simple tables.

- Listing is best represented numerically.

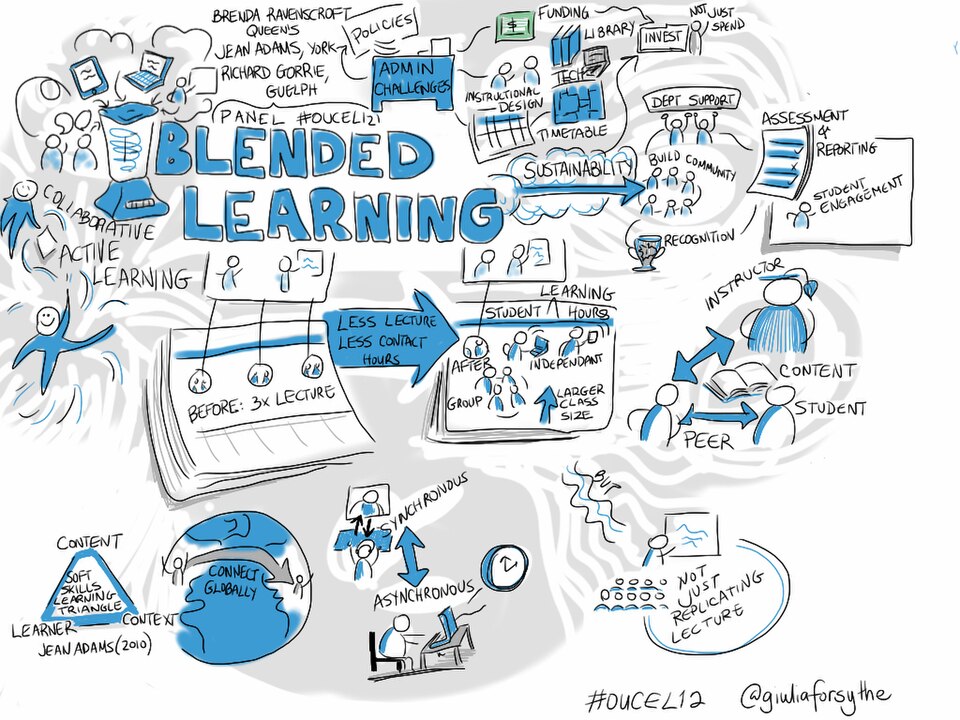

Below is a visual diagram on the topic of blended learning, depicting the history and research on the topic through images. For more examples of handwritten visual diagrams, use the search terms: “visual notes.”

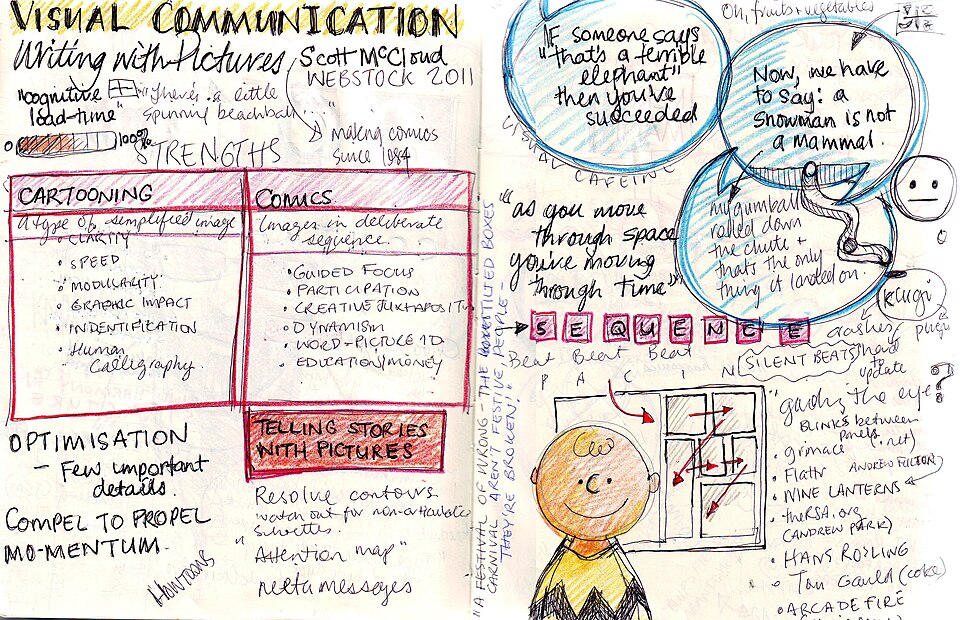

Here is another example … on the topic of visual communication itself.

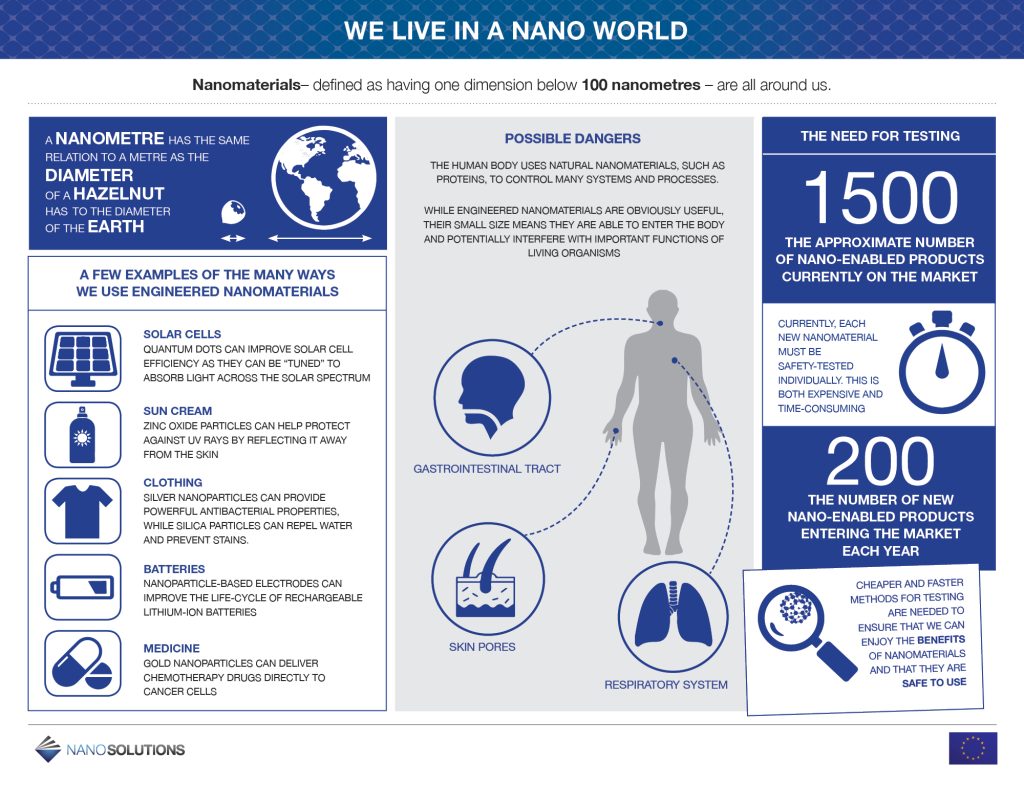

An infographic is a visual representation of the relationship between certain kinds of evidence and often is designed around a pattern of argument. For more examples of digital visual diagrams, use the search terms: “infographics.” The infographic below explains the concept of a nanometer.

Diagramming an Argument

Once we know what the main point of a text is, we can list the supporting details. Then we can determine the relationships (rhetorical patterns) of the supporting details and decide how to represent those relationships visually. There are many ways to create visual notes, some are messy and others are more orderly. Some are created by hand and others electronically. However, as you plot the relationships between the ideas and organize them in a visual field, you use more parts of your brain to process the information, which increases your retention. Many students find that visual notes are an excellent way to study for a test.

Instructions

- In this exercise, you will represent the evidence and pattern of argument of an article using visual relationships.

- You can do this by adding visual elements to your notes as is done in the example above.

- You may instead to do this on a poster board.

- You may even decide to “go big or go home” and make an infographic of the information (just for kicks), but this is not required.

- The important thing to remember is that you are “mapping” the argument. Try to capture the key ideas and represent the relationships between the key ideas through spacing, tables, arrows, lists, graphics, etc.

- You can use the article below, “Isolationism vs. Interventionism,” or you can select a chapter from one of your subject-area classes.

- Power tip: Before you begin your visual, make sure you are noting the signal words in the text you select and that you have reread it to understand the argument pattern. Consider highlighting or annotating to help you do this.

Isolationism vs. Interventionism

U.S. involvement in WWII seems inevitable from our contemporary perspective. As we read of the history of military aggression that led up to the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, we identify a chain of events that seems predestined. However, right up until the “day of infamy” when Japanese bombers sunk four battleships, Americans were locked in an intense debate between isolationism and interventionism.1

Post WWI Isolationist Sentiment

Although the U.S. had only entered World War I at the very end – nineteen months before the Treaty of Versailles – 70% Americans believed that joining the conflict was a mistake. As a result of the fighting, the poisonous gas, and the dismal conditions of the trenches, and the influenza pandemic, over 116,000 American soldiers had perished.2

President Woodrow Wilson was actively involved in the Paris Peace Conference held in 1919, crafting Fourteen Points to guide the negotiations of disarmament. Key among the Fourteen Points was the call for an international peace-keeping congress focused on promoting global freedom and independence of nations.3 President Wilson believed that the establishment of this body was critical to avoiding war in the future. The nations involved in the Paris Peace Conference formed the League of Nations, which predates the current United Nations, but the U.S. Senate voted against joining the League to Wilson’s great disappointment.4

Instead, the US government enacted a series of legislations to discourage U.S. involvement in future foreign wars. These included treaties to constrain the construction of new military boats. The Kellogg-Briand Peace Pact outlawed war. In further efforts to isolate itself, the U.S. passed the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924, which lowered the influx of immigrants by 20% through quotas, which favored wealthier immigrants from northern and western Europe and limited access to immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, specifically targeting Jews and Catholics.5 Thus, the concept of isolationism began.

The Stirrings of WWII

In a decimated and morally broken Germany, Adolf Hitler rose to power in 1933. Conflict in Europe officially began as he marched and armed the Rhineland, a territory along the border with France that Germany lost during WWI. In 1936, Hitler joined Mussolini in the Spanish Civil War, establishing fascism. War in Asia had officially begun earlier when the Japanese Imperial Army invaded the Chinese region of Manchuria.6

With things heating up in both Europe and Asia, most Americans believed that the U.S. should not intervene, but focus on the economic problems at home during the Great Depression. Consequently, Congress passed a series of Neutrality Acts, aimed at keeping the country out of the war by preventing U.S. citizens from doing business with, providing loans to, or embarking on ships of foreign nations involved in the conflict.7

In 1940, Hitler invaded Western Europe, beginning with Netherlands and Belgium. Poland fell after three weeks, France held out only marginally longer. With much of Europe under his dominion, Hitler set his sights on Britain, launching Operation Sea Lion to conquer the British Isles.8

Americans could no longer ignore the urgency of the situation, and Congress passed the Neutrality Act of 1939, which allowed the sale of weapons to the Allied powers involved in the war.9 However, isolationist sentiment was still strong, and U.S. citizens spanning political parties and social identities10 joined the America First Committee (AFC) to lobby for the U.S. to build up its defenses and avoid involvement. They argued that a policy of neutrality, a strong army, and the natural boundaries created by the Atlantic and Pacific would protect America from enemy fire. The AFC actively recruited citizens to its position through news articles, radio broadcasts, and large political gatherings.11

Famous isolationists include Aviator Charles Lindbergh, who was one of the featured speakers. In 1941, he delivered this address: “We are assembled here tonight because we believe in an independent destiny for America. Such a destiny does not mean that we will build a wall around our country and isolate ourselves from contact with the rest of the world. But it does mean that the future of America will not be tied to these eternal wars in Europe. It means that American boys will not be sent across the ocean to die so that England or Germany or France or Spain may dominate the other nations.”12

Another example of an isolationist was US Senator Burton K. Wheeler, a progressive and a pacifist for several reasons. He was raised by a Quaker mother and was deeply impacted by his experiences in Montana as an attorney in WWI when the state banned public demonstrations and restricted the free speech of citizens opposed to the war. He also felt concerned that America was pivoting to be the “world’s policeman.” Wheeler asserted that Britain could fight the war alone and openly voiced his support of their campaign to stop Hitler – just as long as the U.S. was not involved.13

On the other hand, Interventionists argued that protecting Western European democracies, would ultimately protect American from Nazi Germany’s reach. If all of Europe fell, the entire continent would remain under the power of a Fascist dictator, who would control all commerce and negotiations with the U.S. Although America was protected by the oceans, it would be isolated from trade. President Franklin D. Roosevelt explained that it would be like “living at the point of a gun.”14 In counter to the AFC, interventionists created The Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, which focused at “awakening the people of this country to the perils which confront them.” In a rally in New York City, prominent interventionists Edgar Ansel Mowrer, a foreign reporter; Ferdinand Percora, a New York Supreme Court Justice, and Tallulah Bankkead, an actress, buried the heads of two stuffed ostriches at the beach to illustrate FDR’s claim that Wheeler and Lindbergh were sticking their heads in the sand.15

Among the interventionists, were several pro-British groups, and the CDAAA was the most prominent. They advocated to repeal the Neutrality Acts in order to supply Britain with goods and military arms. Willian Allen White, a news editor and author, was the chair of the CDAA. During an interview with the Chicago Daily News, he asserted: “Here is a life and death struggle for every principle we cherish in America: For freedom of speech, of religion, of the ballot and of every freedom that upholds the dignity of the human spirit… Here all the rights that common man has fought for during a thousand years are menaced… The time has come when we must throw into the scales the entire moral and economic weight of the United States on the side of the free peoples of Western Europe who are fighting the battle for a civilized way of life.”16

The Path to War

As Hitler continued his tirade across Europe, public opinion began to change. In the beginning of 1940, 88% of Americans opposed joining the war. In June, the number of citizens who supported helping the British had risen just a few points to 35%. Then the fall France jolted the nation awake. The Nazis focused the strength of their airforce on blitz bombing of London, Liverpool, and Manchester every night from September to May to break the morale of the British people. Despite being out-planed, the Royal Air Force fought back courageously, showing that Hitler could be repelled.17 At the beginning of Hitlers onslaught, many U.S. citizens changed their minds. More than half, 52% of Americans, felt it was worth the risk of war to provide aid to Britian. As the bombing campaign intensified, this increased to 68% by April of 1941.18

Meanwhile, the war in the Pacific progressed. During 1939-1940, the U.S. began to cut its ties with Japan by ending its treaties and cutting off Japanese access to American steel, rubber, and oil. Despite being short resources, Japan continued to invade nations across the Pacific, naming the empire the “Greater East Asia Prosperity Sphere.” In response, the U.S. called upon Japan to relinquish the conquered territory in China. Military planners in Japan, as a consequence, considered American involvement in the war unavoidable, and launched the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor to give the Japanese forces time to prepare. The lives of 2400 Americans, many of them servicemen, were lost in the bombing, and the resistance of the isolationists collapsed. FDR declared war a few hours later with full support of Congress.19

Notes:

- The National WWII Museum New Orleans. (n.d.) The great debate. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/great-debate

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (n.d.) The United States: Isolation-Intervention. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-united-states-isolation-intervention

- United States and the League of Nations. (2025, July 22). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_and_the_League_of_Nations

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (n.d.) The United States: Isolation-Intervention. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-united-states-isolation-intervention

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (n.d.) The United States: Isolation-Intervention. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-united-states-isolation-intervention

- Locke, J. & Wright B. (Eds.)(n.d.) World War II. The American yawp. Stanford University Press. https://www.americanyawp.com/text/24-world-war-ii/

- The National WWII Museum New Orleans. (n.d.) The great debate. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/great-debate

- Locke, J. & Wright B. (Eds.)(n.d.) World War II. The American yawp. Stanford University Press. https://www.americanyawp.com/text/24-world-war-ii/

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (n.d.) The United States: Isolation-Intervention. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-united-states-isolation-intervention

- America First Committee. (2025, July 22). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/America_First_Committee

- The National WWII Museum New Orleans. (n.d.) The great debate. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/great-debate

- Children in History. (n.d.) American World War II interventionists. https://www.histclo.com/essay/war/ww2/cou/us/iso/int/w2u-int.html

- Johnson, M. (2019, September 12). The man behind Montana’s contradictory, confusing, and occasionally crazy political culture. What it Means to be American. https://www.whatitmeanstobeamerican.org/identities/the-man-behind-montanas-contradictory-confusing-and-occasionally-crazy-political-culture/

- The National WWII Museum New Orleans. (n.d.) The great debate. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/great-debate

- Children in History. (n.d.) American World War II interventionists. https://www.histclo.com/essay/war/ww2/cou/us/iso/int/w2u-int.html

- Children in History. (n.d.) American World War II interventionists. https://www.histclo.com/essay/war/ww2/cou/us/iso/int/w2u-int.html

- Locke, J. & Wright B. (Eds.)(n.d.) World War II. The American yawp. Stanford University Press. https://www.americanyawp.com/text/24-world-war-ii/

- The National WWII Museum New Orleans. (n.d.) The great debate. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/great-debate

- Locke, J. & Wright B. (Eds.)(n.d.) World War II. The American yawp. Stanford University Press. https://www.americanyawp.com/text/24-world-war-ii/

Media Attributions

- blended learning © Giulia Forsythe is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Visual_communication_NGLI © JamJar is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 1._Infographic_–_We_live_in_a_nano_world © InsightPublishers is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license