2.4 Annotating Textbooks

Rachel Cox-Vineiz, MA and Erin Thomas, MFA

Annotating: Staying Engaged with a Text

There are two types of readers: passive and active. You get to decide which you are going to be.

Passive Readers

Passive readers are more detached or surface-level in their approach and often distracted while reading. They tend to:

- Read without a clear purpose

- Move through the text without taking time to reflect

- Skip over confusing parts without clarification

- Accept information at face value without questioning

- Forget what they read shortly after the reading is complete

Goal (often unintended): Simply finish the reading.

Result: Minimal understanding, little retention, and weaker engagement.

Active Readers

Active readers are engaged, intentional, and analytical. They interact with the material as they tend to:

- Read with a purpose or a goal in mind

- Pause for reflection about what they’ve read

- Ask questions

- Make predictions

- Highlight or annotate key ideas

- Make connections to prior knowledge

- Summarize or paraphrase sections

Goal: To understand, analyze, and retain the information more deeply. Result: Better comprehension, critical thinking, and recall.

Annotate to Understand

If you want to be an active reader who gains more comprehension and knowledge from reading, annotating is an important tool. To best annotate a textbook, focus on active engagement with the text, keeping your mind alert to what you are reading.

Annotating a text means that you actively engage with it by taking notes as you read, usually by marking the text in some way (underlining, highlighting, using symbols such as asterisks) as well as by writing down brief summaries, thoughts, or questions in the margins of the page. If you are working with a textbook and prefer not to write in it, annotations can be made on sticky notes or on a separate sheet of paper. Regardless of what method you choose, annotating not only directs your focus, but it also helps you retain that information. Furthermore, annotating helps you to recall where important points are in the text if you must return to it for a writing assignment or class discussion.[1]

1. Marking the Text:

- Highlight or Underline: Use these to mark important concepts, definitions, and key terms.

- Circle/Box: Circle vocabulary words or phrases and box out transition words.

- Symbols: Develop a personal system of symbols to represent different ideas (See table below for some suggestions).

- Color code your annotations: Use different colored highlighters or pens for different types of information (e.g., yellow for definitions, orange for questions).

- Use Margins or a Notebook:

- Outlines: Summarize the main ideas of each section.

- Questions: Write down questions you have about the material.

- Personal Responses: Note how the text relates to your own experiences.

- Vocabulary: List unfamiliar words and look them up.

- Focus on what’s important: Try not to mark everything, or the annotations will lose meaning.

2. Additional Tips:

- Create a Key: If using different markings, develop a key to help you remember what each one means.

- Flashcards: For vocabulary, make flashcards to help with memorization.

- Reading Journals: Write a quick summary after reading to capture the main points and questions you may have.

- Be Mindful of Your Learning Style: What note-taking strategies work best for you and your learning style? Develop your own personalized system.

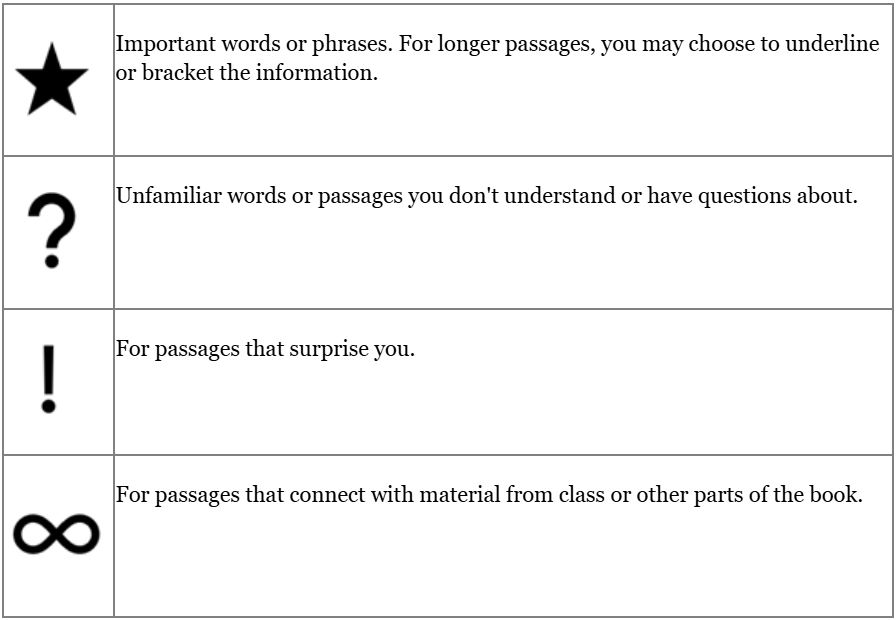

Use Figure 2.4.1 Simple Annotations Table below to help you complete the activity below.

Instructions

- In this exercise, you will annotate a selection of a textbook.

- Preferably, you will select 2-3 pages of a text from one of your subject-matter courses, or you can use the sample textbook selection shown below: “The Great Depression: 23.11 The Lived Experience of the Great Depression” and “The Great Depression: 23:12 Migration and the Great Depression.” [2]

- Follow the instructions above to annotate the text. Select at least three specific symbols/strategies from the instructions to use.

- Answer the following questions about the text you have highlighted:

- Review your annotations. Do they help you remember the key points of the chapter?

- Did you note places you had questions? How can annotating your questions help you understand/retain course material?

- Did annotating help you make connections between the material in the book or lecture?

- Do you remember the system you used for annotating? Is it consistent or did it get more irregular as you went?

- In class only: Compare your annotations with the annotations of a classmate. Explain what you notice:

- Ask your classmate about the system that they used to annotate. Is it similar to or different from yours? Explain.

Sample Textbook Chapter

23.11: The Lived Experience of the Great Depression

In 1934 a woman from Humboldt County, California, wrote to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt seeking a job for her husband, a surveyor, who had been out of work for nearly two years. The pair had survived on the meager income she received from working at the county courthouse. “My salary could keep us going,” she explained, “but—I am to have a baby.” The family needed temporary help, and, she explained, “after that I can go back to work and we can work out our own salvation. But to have this baby come to a home full of worry and despair, with no money for the things it needs, is not fair. It needs and deserves a happy start in life.”1

As the United States slid ever deeper into the Great Depression, such tragic scenes played out time and time again. Individuals, families, and communities faced the painful, frightening, and often bewildering collapse of the economic institutions on which they depended. The more fortunate were spared the worst effects, and a few even profited from it, but by the end of 1932, the crisis had become so deep and so widespread that most Americans had suffered directly. Markets crashed through no fault of their own. Workers were plunged into poverty because of impersonal forces for which they shared no responsibility. With no safety net, they were thrown into economic chaos.

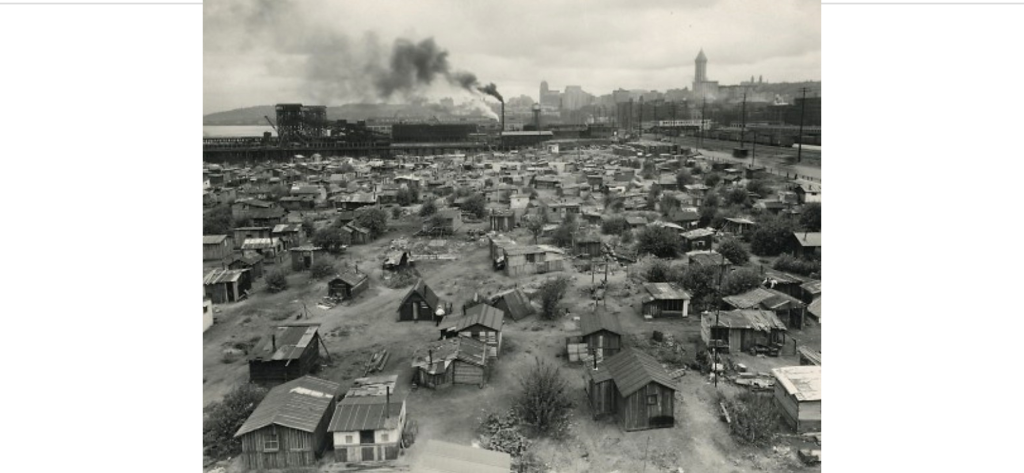

With rampant unemployment and declining wages, Americans slashed expenses. The fortunate could survive by simply deferring vacations and regular consumer purchases. Middle- and working-class Americans might rely on disappearing credit at neighborhood stores, default on utility bills, or skip meals. Those who could borrowed from relatives or took in boarders in homes or “doubled up” in tenements. The most desperate, the chronically unemployed, encamped on public or marginal lands in “Hoovervilles,” spontaneous shantytowns that dotted America’s cities, depending on bread lines and street-corner peddling. Poor women and young children entered the labor force, as they always had. The ideal of the “male breadwinner” was always a fiction for poor Americans, but the Depression decimated millions of new workers. The emotional and psychological shocks of unemployment and underemployment only added to the shocking material depravities of the Depression. Social workers and charity officials, for instance, often found the unemployed suffering from feelings of futility, anger, bitterness, confusion, and loss of pride. Such feelings affected the rural poor no less than the urban.2

23.12: Migration and the Great Depression

On the Great Plains, environmental catastrophe deepened America’s longstanding agricultural crisis and magnified the tragedy of the Depression. Beginning in 1932, severe droughts hit from Texas to the Dakotas and lasted until at least 1936. The droughts compounded years of agricultural mismanagement. To grow their crops, Plains farmers had plowed up natural ground cover that had taken ages to form over the surface of the dry Plains states. Relatively wet decades had protected them, but, during the early 1930s, without rain, the exposed fertile topsoil turned to dust, and without sod or windbreaks such as trees, rolling winds churned the dust into massive storms that blotted out the sky, choked settlers and livestock, and rained dirt not only across the region but as far east as Washington, D.C., New England, and ships on the Atlantic Ocean. The Dust Bowl, as the region became known, exposed all-too-late the need for conservation. The region’s farmers, already hit by years of foreclosures and declining commodity prices, were decimated.3 For many in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas who were “baked out, blown out, and broke,” their only hope was to travel west to California, whose rains still brought bountiful harvests and—potentially—jobs for farmworkers. It was an exodus. Oklahoma lost 440,000 people, or a full 18.4 percent of its 1930 population, to outmigration.4

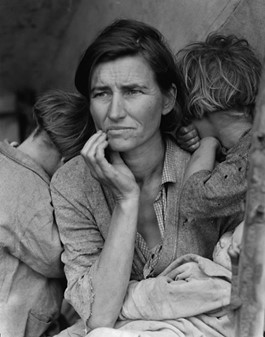

Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother became one of the most enduring images of the Dust Bowl and the ensuing westward exodus. Lange, a photographer for the Farm Security Administration, captured the image at a migrant farmworker camp in Nipomo, California, in 1936. In the photograph a young mother stares out with a worried, weary expression. She was a migrant, having left her home in Oklahoma to follow the crops to the Golden State. She took part in what many in the mid-1930s were beginning to recognize as a vast migration of families out of the southwestern Plains states. In the image she cradles an infant and supports two older children, who cling to her. Lange’s photo encapsulated the nation’s struggle. The subject of the photograph seemed used to hard work but down on her luck, and uncertain about what the future might hold.

The Okies, as such westward migrants were disparagingly called by their new neighbors, were the most visible group who were on the move during the Depression, lured by news and rumors of jobs in far-flung regions of the country. By 1932, sociologists were estimating that millions of men were on the roads and rails traveling the country. Economists sought to quantify the movement of families from the Plains. Popular magazines and newspapers were filled with stories of homeless boys and the veterans-turned- migrants of the Bonus Army commandeering boxcars. Popular culture, such as William Wellman’s 1933 film, Wild Boys of the Road, and, most famously, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939 and turned into a hit movie a year later, captured the Depression’s dislocated populations.

These years witnessed the first significant reversal in the flow of people between rural and urban areas. Thousands of city dwellers fled the jobless cities and moved to the country looking for work. As relief efforts floundered, many state and local officials threw up barriers to migration, making it difficult for newcomers to receive relief or find work. Some state legislatures made it a crime to bring poor migrants into the state and allowed local officials to deport migrants to neighboring states. In the winter of 1935–1936, California, Florida, and Colorado established “border blockades” to block poor migrants from their states and reduce competition with local residents for jobs. A billboard outside Tulsa, Oklahoma, informed potential migrants that there were “NO JOBS in California” and warned them to “KEEP Out.”5

Sympathy for migrants, however, accelerated late in the Depression with the publication of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. The Joad family’s struggles drew attention to the plight of Depression-era migrants and, just a month after the nationwide release of the film version, Congress created the Select Committee to Investigate the Interstate Migration of Destitute Citizens. Starting in 1940, the committee held widely publicized hearings. But it was too late. Within a year of its founding, defense industries were already gearing up in the wake of the outbreak of World War II, and the “problem” of migration suddenly became a lack of migrants needed to fill war industries. Such relief was nowhere to be found in the 1930s.

Americans meanwhile feared foreign workers willing to work for even lower wages. The Saturday Evening Post warned that foreign immigrants, who were “compelled to accept employment on any terms and conditions offered,” would exacerbate the economic crisis.6 On September 8, 1930, the Hoover administration issued a press release on the administration of immigration laws “under existing conditions of unemployment.” Hoover instructed consular officers to scrutinize carefully the visa applications of those “likely to become public charges” and suggested that this might include denying visas to most, if not all, alien laborers and artisans. The crisis itself had stifled foreign immigration, but such restrictive and exclusionary actions in the first years of the Depression intensified its effects. The number of European visas issued fell roughly 60 percent while deportations dramatically increased. Between 1930 and 1932, fifty-four thousand people were deported. An additional forty-four thousand deportable aliens left “voluntarily.”7

Exclusionary measures hit Mexican immigrants particularly hard. The State Department made a concerted effort to reduce immigration from Mexico as early as 1929, and Hoover’s executive actions arrived the following year. Officials in the Southwest led a coordinated effort to push out Mexican immigrants. In Los Angeles, the Citizens Committee on Coordination of Unemployment Relief began working closely with federal officials in early 1931 to conduct deportation raids, while the Los Angeles County Department of Charities began a simultaneous drive to repatriate Mexicans and Mexican Americans on relief, negotiating a charity rate with the railroads to return Mexicans “voluntarily” to their mother country. According to the federal census, from 1930 to 1940 the Mexican-born population living in Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas fell from 616,998 to 377,433. Franklin Roosevelt did not indulge anti-immigrant sentiment as willingly as Hoover had. Under the New Deal, the Immigration and Naturalization Service halted some of the Hoover administration’s most divisive practices, but with jobs suddenly scarce, hostile attitudes intensified, and official policies less than welcoming, immigration plummeted and deportations rose. Over the course of the Depression, more people left the United States than entered it.8

- Mrs. M. H. A. to Eleanor Roosevelt, June 14, 1934, in Robert S. McElvaine, ed., Down and Out in the Great Depression: Letters from the Forgotten Man (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983), 54–55.

- See especially Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), chap. 5).

- Robert S. McElvaine, ed., Encyclopedia of the Great Depression (New York: Macmillan, 2004), 320.

- Donald Worster, Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 48

- James N. Gregory, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 22.

- Cybelle Fox, Three Worlds of Relief (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), 126.

- Ibid., 127.

- Aristide Zolberg, A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America (New York: Sage, 2006), 269.

This page titled 23.12: The Lived Experience of the Great Depression is shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by American YAWP (Stanford University Press) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.

This page titled 23.13: Migration and the Great Depression is shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by American YAWP (Stanford University Press) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.

Media Attributions

- Annotating Table © Erin Thomas is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Hooverville © Warner, H.M. is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- destitute mother © Dorothea Lange is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Okies © Dorothea Lange is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Browning, E. (2018). Chapter 1 -- Critical Reading. In Let's Get Writing! Virginia Western Community College. https://pressbooks.pub/vwcceng111/chapter/chapter-1-critical-reading/ "Let's Get Writing" by Elizabeth Browning is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Corbett, P. S., Janssen, V., Lund, J. M., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. (2017). The Lived Experience of the Great Depression. In U.S. History (Unit 23.11). Migration and the Great Depression. In U.S. History (Unit 23.12). OpenStax. https://oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/15521 ↵