2.3 Highlighting Textbooks

Rachel Cox-Vineiz, MA and Erin Thomas, MFA

Highlighting: An Effective Study Skill

Why Highlighting?

Why do students highlight? Usually, it’s to mark important parts of the text for later study. But instead of thinking critically, they often spend more energy sorting and deciding what to highlight, rather than truly understanding the material.

Many may rely on these highlights as their main study tool, rereading them and mistaking familiarity for true understanding. Repeatedly seeing the same words can create an illusion of competence—feeling like we know the material when we don’t. Even if we remember the highlighted points, it doesn’t mean we grasp the bigger picture or can apply, analyze, or evaluate the information—key skills professors test for.

Fight the Temptation!

Highlighting can be a great studying tool–it depends on what you highlight and how you use it. Some students find it helpful because it keeps them engaged with the text. If that’s you, great—keep doing what works! But be mindful of the temptation to highlight everything on a page or in a paragraph, which defeats the purpose and makes it harder to identify key points later. Read ahead for tips on how to highlight effectively and engage more deeply while studying.

Guidelines for Effective Highlighting

- Read First, Then Highlight – Develop the habit of reading a paragraph or section before highlighting. This allows you to determine the most important points rather than marking text impulsively.

- Be Selective – Highlight only essential information, such as main ideas, key terms, and supporting details. Avoid highlighting entire sentences.

- Ensure Accuracy – Double-check that what you highlight accurately conveys the main ideas and supporting information. Don’t mistake examples or contrasting ideas for the main point.

- Be Consistent – Decide on a system for highlighting (e.g., using different colors for main ideas vs. key terms) and stick with it to make review easier.

- Use Color-Coding – Assign different colors for main ideas, definitions, and examples.

- Utilize Digital Tools – If reading online, use annotation features in PDF readers or e-textbook platforms like Vital Source.

- Review Your Highlights – Reread only the highlighted sections later and quiz yourself on the key concepts.

- Test Your Understanding – After highlighting, try to summarize the key points in your own words. If your highlights don’t make sense on their own, adjust them before moving on.

Effective Reading Strategies to Use Alongside Highlighting

Highlighting should also be combined with other reading strategies to ensure deep understanding. Below are guidelines and strategies to help you highlight effectively and enhance your reading comprehension. While highlighting can help identify key points, using other strategies will improve comprehension and retention:

- Set a Purpose for Reading – Know what you need to learn and check if you’ve met that goal after reading.

- Preview the Text – Before reading, scan headings, bold words, charts, and end-of-chapter questions to get an overview of the material.

- Ask and Answer Questions – Turn headings into questions and answer them while reading.

- Annotate – Take brief notes in the margins or a separate notebook to summarize key concepts.

- Summarize – Pause after each section to briefly summarize the key ideas in your own words.

By following these strategies, you can turn highlighting from a passive habit into an active study tool that enhances your understanding and retention of course material.

Instructions

- In this exercise, you will highlight a selection of a textbook.

- Preferably, you will select 2-3 pages of a text from one of your subject-matter courses, or you use can use the sample textbook selection shown below: “The Great Depression: 23.9 The Origins of the Great Depression.”[1]

-

Follow the instructions above to highlight the text.

- Answer the following questions about the text you have highlighted:

- Reread your the text, only reading the highlighted items. Did you highlight enough to remember the key points of the chapter?

- Can you follow the chapter’s line of reasoning, logic, or argument by reading only the items you highlighted?

- Are your highlights distracting? (usually this happens when you’ve highlighted the wrong information or too much information)?

- Are your highlights confusing? (usually this happens when you’ve highlighted too many details instead of main ideas)

- Do you remember the system you used for highlighting? Is it consistent or did it get more irregular as you went?

- In class only: Compare your highlights with the highlights of a classmate. Explain what you notice:

- Did your classmate highlight most of the same ideas?

- Did your classmate highlight more or less than you did?

- Ask your classmate about the system that they used to highlight. Is it similar or different to yours? Explain.

Sample Textbook Chapter

23.7: The Origins of the Great Depression

On Thursday, October 24, 1929, stock market prices suddenly plummeted. Ten billion dollars in investments (roughly equivalent to about $100 billion today) disappeared in a matter of hours. Panicked selling set in, stock values sank to sudden lows, and stunned investors crowded the New York Stock Exchange demanding answers. Leading bankers met privately at the offices of J. P. Morgan and raised millions in personal and institutional contributions to halt the slide. They marched across the street and ceremoniously bought stocks at inflated prices. The market temporarily stabilized but fears spread over the weekend and the following week frightened investors dumped their portfolios to avoid further losses. On October 29, Black Tuesday, the stock market began its long precipitous fall. Stock values evaporated. Shares of U.S. Steel dropped from $262 to $22. General Motors stock fell from $73 a share to $8. Four fifths of J. D. Rockefeller’s fortune—the greatest in American history—vanished.

Although the crash stunned the nation, it exposed the deeper, underlying problems with the American economy in the 1920s. The stock market’s popularity grew throughout the decade, but only 2.5 percent of Americans had brokerage accounts; the overwhelming majority of Americans had no direct personal stake in Wall Street. The stock market’s collapse, no matter how dramatic, did not by itself depress the American economy. Instead, the crash exposed a great number of factors that, when combined with the financial panic, sank the American economy into the greatest of all economic crises. Rising inequality, declining demand, rural collapse, overextended investors, and the bursting of speculative bubbles all conspired to plunge the nation into the Great Depression.

Despite resistance by Progressives, the vast gap between rich and poor accelerated throughout the early twentieth century. In the aggregate, Americans were better off in 1929 than in 1920. Per capita income had risen 10 percent for all Americans, but 75 percent for the nation’s wealthiest citizens.1 The return of conservative politics in the 1920s reinforced federal fiscal policies that exacerbated the divide: low corporate and personal taxes, easy credit, and depressed interest rates overwhelmingly favored wealthy investors who, flush with cash, spent their money on luxury goods and speculative investments in the rapidly rising stock market.

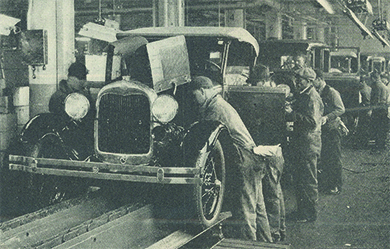

The pro-business policies of the 1920s were designed for an American economy built on the production and consumption of durable goods. Yet by the late 1920s, much of the market was saturated. The boom of automobile manufacturing, the great driver of the American economy in the 1920s, slowed as fewer and fewer Americans with the means to purchase a car had not already done so. More and more, the well-to-do had no need for the new automobiles, radios, and other consumer goods that fueled gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the 1920s. When products failed to sell, inventories piled up, manufacturers scaled back production, and companies fired workers, stripping potential consumers of cash, blunting demand for consumer goods, and replicating the downward economic cycle. The situation was only compounded by increased automation and rising efficiency in American factories. Despite impressive overall growth throughout the 1920s, unemployment hovered around 7 percent throughout the decade, suppressing purchasing power for a great swath of potential consumers.2

For American farmers, meanwhile, hard times began long before the markets crashed. In 1920 and 1921, after several years of larger-than-average profits, farm prices in the South and West continued their long decline, plummeting as production climbed and domestic and international demand for cotton, foodstuffs, and other agricultural products stalled. Widespread soil exhaustion on western farms only compounded the problem. Farmers found themselves unable to make payments on loans taken out during the good years, and banks in agricultural areas tightened credit in response. By 1929, farm families were overextended, in no shape to make up for declining consumption, and in a precarious economic position even before the Depression wrecked the global economy.3

Despite serious foundational problems in the industrial and agricultural economy, most Americans in 1929 and 1930 still believed the economy would bounce back. In 1930, amid one of the Depression’s many false hopes, President Herbert Hoover reassured an audience that “the depression is over.”4 But the president was not simply guilty of false optimism. Hoover made many mistakes. During his 1928 election campaign, Hoover promoted higher tariffs as a means for encouraging domestic consumption and protecting American farmers from foreign competition. Spurred by the ongoing agricultural depression, Hoover signed into law the highest tariff in American history, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, just as global markets began to crumble. Other countries responded in kind, tariff walls rose across the globe, and international trade ground to a halt. Between 1929 and 1932, international trade dropped from $36 billion to only $12 billion. American exports fell by 78 percent. Combined with overproduction and declining domestic consumption, the tariff exacerbated the world’s economic collapse.5

But beyond structural flaws, speculative bubbles, and destructive protectionism, the final contributing element of the Great Depression was a quintessentially human one: panic. The frantic reaction to the market’s fall aggravated the economy’s other many failings. More economic policies backfired. The Federal Reserve overcorrected in their response to speculation by raising interest rates and tightening credit. Across the country, banks denied loans and called in debts. Their patrons, afraid that reactionary policies meant further financial trouble, rushed to withdraw money before institutions could close their doors, ensuring their fate. Such bank runs were not uncommon in the 1920s, but in 1930, with the economy worsening and panic from the crash accelerating, 1,352 banks failed. In 1932, nearly 2,300 banks collapsed, taking personal deposits, savings, and credit with them.6

The Great Depression was the confluence of many problems, most of which had begun during a time of unprecedented economic growth. Fiscal policies of the Republican “business presidents” undoubtedly widened the gap between rich and poor and fostered a standoff over international trade, but such policies were widely popular and, for much of the decade, widely seen as a source of the decade’s explosive growth. With fortunes to be won and standards of living to maintain, few Americans had the foresight or wherewithal to repudiate an age of easy credit, rampant consumerism, and wild speculation. Instead, as the Depression worked its way across the United States, Americans hoped to weather the economic storm as best they could, waiting for some form of relief, any answer to the ever-mounting economic collapse that strangled so many Americans’ lives.

- Balderrama, Francisco E., and Raymond Rodríguez. Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s, rev. ed. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

- Brinkley, Alan. The End of Reform: New Deal Liberalism in Recession and War. New York: Knopf, 1995.

- ———. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression. New York: Knopf, 1982.

- Cohen, Lizabeth. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Cowie, Jefferson, and Nick Salvatore. “The Long Exception: Rethinking the Place of the New Deal in American History.” International Labor and Working-Class History 74 (Fall 2008): 1–32.

- Dickstein, Morris. Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression. New York: Norton, 2009.

This page titled 23.9: The Origins of the Great Depression is shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by American YAWP (Stanford University Press) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.

Media Attributions

- NY Stock Exchange © Unknown Author is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Assembly line Ford © Literary Digest 1928-01-07 Henry Ford Interview / Photographer unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Corbett, P. S., Janssen, V., Lund, J. M., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. (2017). The Great Depression. In U.S. History (Unit 25.2). OpenStax. https://oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/15521 ↵