1.3 Learning and Attention

Erin Thomas, MFA

What is Attention?

As explained previously, learning cannot happen without attention, so what is attention exactly? The short answer is a complex interplay between the information gathered by your senses: taste, smell, touch, hearing, and sight; and how your frontal cortex processes this information. Information moves through your brain through the frontal cortex, which is the newest and most human part of your brain, to long-term memory. Attention describes the process your brain uses to decide what information is relevant, and what information is not relevant. Unless information gets our attention, we will not be able to comprehend or remember it.

Consider this definition of attention by Wayne Wu from the Open Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science:

When agents pay attention, they do so selectively across modalities of mind such as perception and cognition. For example, they visually search for a friend in a crowd to signal to them or interpret a painting by scrutinizing it. They listen to an interlocutor to understand what is being said or secretly surveil a conversation to hear if they are being talked about. They memorize phone numbers to dial later or recall past events to answer a question. They reason through trains of thought or are pulled along by random ideas when the mind wanders. Sometimes attention is firmly controlled, as when focusing on work to meet a looming deadline. Other times attention is lured away, as when social media habits lead to involuntarily doom scrolling in an app.[1]

If you are having trouble remembering what you read or studying for your exams, you are struggling with an issue of attention. Therefore, learning how to capture and maintain your attention is key to your success as a student. Section 1.2 provides the C.I.T.E. learning style assessment. Once more, the purpose of this questionnaire is not to describe how you will learn best in every situation, but to give you some ideas of study approaches that may help you control your attention more effectively.

In this course, we will refer to the process of paying attention as “noticing.” Once we notice, we begin the process of holding our attention. One of the best ways to do this is to take an interest, so an effective brain hack is to consciously trick yourself into believing that the school subjects that you find the dullest are the most engaging and riveting. To fully understand how noticing results in learning, we must examine how memory works.

Memory

The personal computer was designed on the concept of the human brain: an operating system runs your apps in real time and a hard drive stores information in bites for later reference. Likewise, memory is classified as short-term or “working memory” and long-term memory. In order to turn information to learning, it needs to travel from your working memory to long-term memory. The first step in this process is noticing, and then by taking an interest, you help your brain transfer this information into storage.

Graham J. Hitch and Alan D. Baddeley in the Open Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science define working memory as follows:

Working memory refers to the psychological limit on our capacity to attend to and manipulate stored temporary information in goal-directed thought and behavior. A classic example is mental calculation, where the task involves holding numbers in mind at the same time as shifting attention to operate on component digits and arrive at a result. Temporary storage involves maintaining novel information over time intervals of seconds or at most a few minutes and can be usefully contrasted with our capacity to store vast amounts of previously acquired information in long-term memory over intervals up to a lifetime. Attention is the process we use to focus on a selection of information in working memory, the external environment, or long-term memory.[2]

Like an operating system, your working memory is extremely limited, while as explained by Hitch and Baddeley, the information in long-term memory can last a lifetime. One of our biggest challenges as students is learning how to control and direct our working memory. The following five key concepts help us understand more fully how working memory functions:

- Capacity: working memory can only store 3 to 7 items at a time. Also, it can only store this information for minutes to milliseconds before it is forgotten.

- Dual-task inference (distraction): because working memory is limited, when we try to complete two different tasks at the same time, they interfere with each other.

- Attention: this is the mechanism through which the information in working memory is selected and processed.

- High turn-over: information in working memory that is not paid attention to will quickly be forgotten.

- Reciprocal relationship with long term memory: working memory determines what is stored in long-term memory. However, if information is stored in long-term memory, it helps us retain that same information when we encounter it again in working memory.[3]

The Central Executive

We are constantly bombarded by information, which requires our brain to sort the relevant from the irrelevant in milliseconds . . . You are at a baseball game. The person next to you is eating popcorn and a corn dog. The sun is beating down on the back of your neck, and you realize it’s time to pull out your sunscreen. Your cousin is up to bat next, and you are watching the pitcher wind up. Suddenly, you notice a foul ball coming towards your head from the field adjacent — you duck just in time. This is thanks to the central executive, which sorts through all the sensory information to isolate the one input necessary to ensure your survival.

What is the central executive? It’s basically the CEO in the frontal cortex of your brain, deciding what you are going to pay attention to and what you are going to ignore. The human brain hasn’t changed much since prehistoric times, and it is especially designed to save us from a rampaging buffalo. If we fail our history exam, our life is not necessarily in danger, but we may have to pay more tuition for next semester. For the sake of financial survival and our future career, we need to purposely engage our brain CEO to help us sort out the information that is going to be on the test. And because it isn’t an oncoming buffalo or baseball, we need to let our brain know when to pay attention.

The central executive isn’t a thing but rather a process that controls your working memory. However, in order to better understand how working memory operates, we are going to give the central executive a name: Regina. She sits at an enormous floating office desk covered with stacks of paper. Meanwhile, pieces of paper shoot in through her office door. She deftly snatches these pieces of paper, glances at them, and decides in milliseconds if she is going to toss the paper behind her head into an enormous heap. The information at the bottom of the heap disintegrates into the ether below Regina’s feet, where there is only air.

Occasionally, she will glance longer at a piece of paper and quickly store it in a file cabinet on her right, from which a courier collects files and carries them to long-term memory. In the seconds she pauses on relevant information, pieces of paper keep shooting through the door, landing on the floor and disintegrating immediately.

The pieces of paper that land on the floor are unattended information, the pieces of paper Regina touches are given some level of attention, and the papers Regina files are those that you will remember. Regina has a hard job, and if you are scrolling on your phone during history class, the chances that you remember anything about the Paris Peace Treaty after WWII are next to nothing. If you are only interested in watching Netflix or sports on ESPN, Regina will only remember baseball stats or who Ginny is dating. In order to get Regina to pay attention during history, you have to pay attention, notice, and take an interest.

However, there is a reciprocal relationship between short-term and long-term memory. If you pay attention during one history class, it’s much easier to pay attention during the next one. If you have heard something before, Regina is much more likely to pay attention. This is why reading is so essential: the more we read, the easier it is to learn from reading. We encounter words, patterns, and concepts again and again, which reinforces the neural networks between the working memory in our frontal cortex and our long-term memory.

NRRC Framework

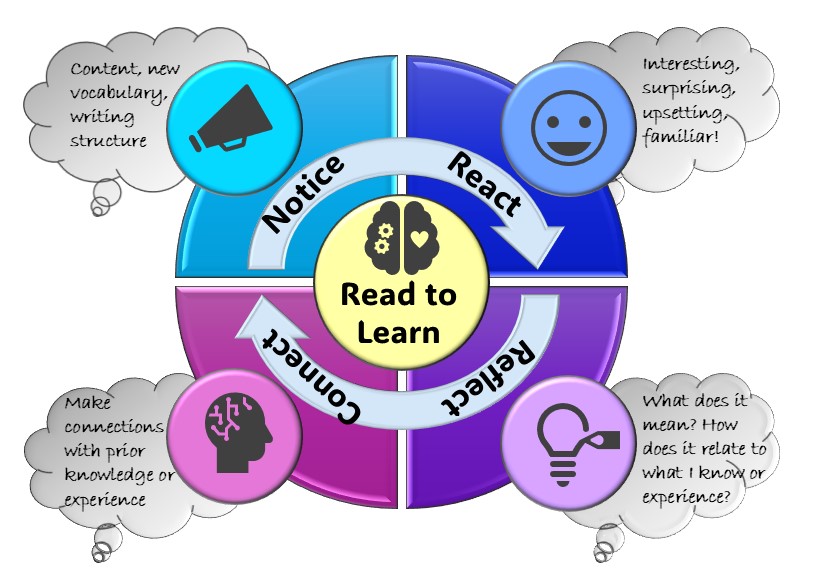

In this course, we will use the NRRC Framework, which provides a simple illustration of the actions we can take to more successfully move important information from our working memory to our long-term memory. NRRC stands for Notice, React, Connect, and Reflect:

- Notice: Noticing is the act of focusing your attention on information. You can notice different attributes of information or a text, such as the content, new vocabulary, or structure. It is impossible to notice all these elements simultaneously, so in this course, we will use re-reading as a strategy to reinforce our understanding.

- React: Reacting to information is critical to signal to your central executive that the information needs to be stored long-term. When you react, you may find information interesting, surprising, unsettling, or familiar. It’s important to have both an intellectual and emotional reaction to information to solidify your retention. Reacting is a core tenet of active reading, which we will address later in Chapter 4: Active Reading of this textbook.

- Reflect: Learning happens both consciously and subconsciously. When we reflect on what we learn, we increase our attention on that information in our frontal cortex, which prepares our brain to move information from working memory to long-term memory. It also reinforces our emotional reaction to information, which promotes storage. As we reflect, we increase our concentration, which blocks out distractions, so we can more fully comprehend. Reflecting prepares the way for the next step, making connections.

- Connect: Integrating information into what you already know makes it much easier to recall. You can do this by making connections with things you have learned or experienced before. When you connect new information with old information, you create literal neural networks and connections in your brain, so once you learn something, make an effort to tie it in!

Throughout this workbook and course, we will refer to the NRRC Framework as a simple way to visualize moving information from your working memory to long-term memory.

Instructions

- Watch the following YouTube videos that introduce some of the ideas in this reading selection. Using multimedia to introduce new ideas can help you retain information/read faster.

- Read this Medium article with quotes from the Science of Remembering and the Art of Forgetting. (Link will open in new window.)

- Consider the following questions:

- Explain three ideas that you learned from these videos and the article.

- How can you apply these ideas to increasing your memory and attention? Explain.

- Complete the following two activities.

- During a 30-60 minute study session, track how many times you look at your phone/surf the Internet. Do this by putting a paperclip or a penny in a jar/cup every time you look at your phone.

- During a 30-60 minute study session, set your alarm in 15 or 30 minute increments. Using the chart, check in with yourself and evaluate your attention. Fill out the attention checklist.

- Consider the following questions:

- How many times did you look at your phone/surf the Internet? What does this tell you about your attention? How can you improve your attention by managing your relationship with technology?

- What did you learn about your attention by filling out the attention checklist. What do you think you can do to improve your focus based on this activity?

Table 1.3.1: Assignment: Attention Checklist Template

| Behavior/thought process | 1st Check

Number |

2nd Check

Number |

What is a strategy I can use to address this? |

|---|---|---|---|

| How many times did I try to start before I actually started studying? | |||

| How many times did I stop and take a break? Or feel like taking a break? | |||

| How many times did I feel hungry or thirsty? | |||

| How many times did I feel restless or fidgety? | |||

| How many times did I lose my place and have to start over or reread? | |||

| How many times did I almost fall asleep? | |||

| How many times did I experience brain fog or feel mentally blurred? | |||

| How many times did I stop and stare at the screen or the book and completely space out? | |||

| How many times did I catch myself having negative thoughts or wanting to give up? |

Media Attributions

- Graphic NRRC © Erin Thomas is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Wu, W. (2024, July 24). Attention. Open Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science. Retrieved July 28, 2025, from https://oecs.mit.edu/pub/xdqgwrkq/release/1 ↵

- Hitch, G. J., & Baddeley, A. D. (2024, September 24). Working memory. Open Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science. Retrieved July 28, 2025, from https://oecs.mit.edu/pub/1rgtz41v/release/1 ↵

- Hitch, G. J., & Baddeley, A. D. (2024, September 24). Working Memory. Open Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science. Retrieved July 28, 2025, from https://oecs.mit.edu/pub/1rgtz41v/release/1 ↵