6.5 Identifying a Claim

Erin Thomas, MFA

What is an Argument?

Believe it or not, experts throughout history have spent a lot of time defining the “rules of argument” because discussing issues is a fundamental part of what it means to be a human. They have created various paradigms of how to argue fairly, so arguments are productive and people are able to discuss issues without getting angry. Also, a fundamental part of exchanging ideas with another person is learning. We can’t learn from a claim unless we clearly identify what that claim is.

“Logical fallacies” are one way that people violate the fair rules of discussion. A common logical fallacy is the “straw man,” defined as:

Straw man fallacy: can take different forms and may involve: Taking an opponent’s words out of context (i.e., choosing words that misrepresent their intention) Exaggerating or oversimplifying an opponent’s argument and then attacking this distorted version.

Unfortunately in the political arena, candidates frequently break the rules of argument and misinterpret the meaning and intentions of their opponents on purpose. This has normalized uncivil discourse, which has had a souring impact on how we exchange ideas in society at large. So, the first step in civil discourse is this: clearly understand an argument or the claim posed by a text or speech.

Defining Argument

The word “argument” often implies a confrontation, a clash of opinions and personalities, or just a plain verbal fight. It implies a winner and a loser, a right side and a wrong one. Because of this understanding of the word “argument,” many students think the only type of argument writing is the debate-like position paper, in which the author defends his or her point of view against other, usually opposing, points of view.

These two characteristics of argument—as controversial and as a fight—limit the definition because arguments come in different disguises, from hidden to subtle to commanding. It is useful to look at the term “argument” in a new way. What if we think of argument as an opportunity for conversation, for sharing with others our point of view on an issue, for showing others our perspective of the world? What if we think of argument as an opportunity to connect with the points of view of others rather than defeating those points of view?

At school, at work, and in life, argument is one of main ways we exchange ideas with one another. Academics, business people, scientists, and other professionals all make arguments to determine what to do or think or to solve a problem by enlisting others. Not surprisingly, argument dominates writing, and training in argument writing is essential for all college students. Anytime you make a claim and then support the claim with reasons, you are making an argument. Consider the following:

- A teenager convincing parents to borrow the car may include reasons such as a track record of responsibility, a high score on the driver’s test, and promises to follow all driving parental rules and regulations, such as wearing a seatbelt.

- An employee persuading the boss to give her a raise may include concrete evidence, such as sales records, no missed days, or personal testimonies from satisfied customers.

- A gardener selling crops at a farmer’s market convinces buyers that his produce is better because he used heirloom seeds and organic soil and watered regularly.

Arguments in an academic setting typically include rhetorical appeals: logos, pathos, and ethos, which are explained Chapter 7: Assessing Bias and Reliability combined with research to back up claims. Arguments, no matter how passionate or well-reasoned, are typically not considered valid in college without evidence in the form of facts and statistics. Often academic writing is divided into two categories: argumentative and non-argumentative. According to this view, to be argumentative, writing must have the following qualities: It has to defend a position in a debate between two or more opposing sides, it must be on a controversial topic, and the goal of such writing must be to prove the correctness of one point of view over another.

In your English courses, you may have an opportunity to compose a Literature Review, a compilation of the most recent research on the topic. This type of paper is not “argumentative” in the strictest sense because they are written with a factual and dispassionate tone. However, a Literature Review is the first section of a research study, which is intended as a mode of communication between a community for scholars to share ideas. Researchers advance their research theses to disseminate the latest research and promote new ways of thinking about topics. Biologists, for example, do not gather data and write up analyses of the results because they wish to fight with other biologists, even if they disagree with the ideas of other biologists. They wish to share their discoveries and get feedback on their ideas. When historians put forth an argument, they do so often while building on the arguments of other historians who came before them. Literature scholars publish their interpretations of different works of literature to enhance understanding and share new views, not necessarily to have one interpretation replace all others.

There may be debates within any field of study, but those debates can be healthy and constructive if they mean even more scholars come together to explore the ideas involved in those debates. Thus, be prepared for your college professors to have a much broader view of argument than a mere fight over a controversial topic.[1]

Evaluating Claims

In almost every college class, we are asked to read someone else’s writing, explain what that person is arguing, and point out the strengths and weaknesses of their argument. This chapter offers tools for figuring out the structure of an argument and describing it. In later chapters, we will talk about responding to arguments and analyzing how arguments play on emotion and gain the audience’s trust. When you are just trying to get the basic ideas about something you have read straight, how do you go about it? An argument is composed of intricate clusters of words. How do you get to the heart of it?

In this chapter we look at how to take notes not just on the meaning of each part of the argument but also on its relation to the other parts. Then we use these notes to analyze the argument, so it is more clear how each supporting detail points us toward the claim. We see how each element implies, supports, limits, or contradicts other elements. As a result, we begin to see where the argument is vulnerable and how it might be modified.[2]

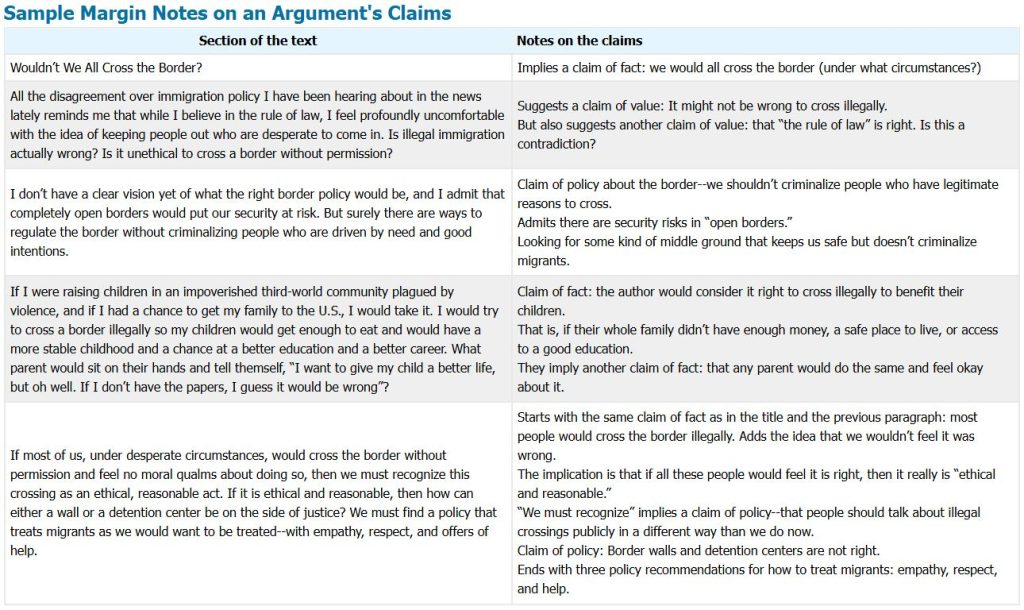

A first step toward summarizing and responding to an argument is to first make margin notes on the claims. Let’s take the following argument as an example:

Sample Argument: “Wouldn’t We All Cross the Border?”

All the disagreement over immigration policy I have been hearing about in the news lately reminds me that while I believe in the rule of law, I feel profoundly uncomfortable with the idea of keeping people out who are desperate to come in. Is illegal immigration actually wrong? Is it unethical to cross a border without permission?

I don’t have a clear vision yet of what the right border policy would be, and I admit that completely open borders would put our security at risk. But surely there are ways to regulate the border without criminalizing people who are driven by need and good intentions.

If I were raising children in an impoverished third-world community plagued by violence, and if I had a chance to get my family to the U.S., I would take it. I would try to cross a border illegally so my children would get enough to eat and would have a more stable childhood and a chance at a better education and a better career. What parent would sit on their hands and tell themself, “I want to give my child a better life, but oh well. If I don’t have the papers, I guess it would be wrong”?

If most of us, under desperate circumstances, would cross the border without permission and feel no moral qualms about doing so, then we must recognize this crossing as an ethical, reasonable act. If it is ethical and reasonable, then how can either a wall or a detention center be on the side of justice? We must find a policy that treats migrants as we would want to be treated–with empathy, respect, and offers of help.

In 2.4 Annotating Textbooks, we reviewed how to make marginal notes as you read, and paraphrasing an argument on your second read can help you identify the main claims. As you make notes, it is worth identifying the different kinds of claims: policy, fact, and value, which are explained below. Compare the graphic below with the original text, “Wouldn’t We All Cross the Border” above.

Notice that attempting to summarize each claim can actually take more space than the original text itself if we are summarizing in detail. Completing a detailed table isn’t necessary for each text we are assigned to evaluate, but it can help when the argument is hard to follow, the text is extremely technical, or when it’s important to be precise.[3]

Types of Claims

Claims of Policy

The most familiar kind of argument demands action. It is easy to see when the writer is asking readers to do something. Here are a few phrases that signal a claim of policy, a claim that is pushing readers to do something:

- We should _____________.

- We ought to _____________.

- We must _____________.

- Let’s _____________.

- The best course is _____________.

- The solution is to _____________.

- The next step should be _____________.

- We should consider _____________.

- Further research should be done to determine _____________.

Here are a few sample claims of policy:

- Landlords should not be allowed to raise the rent more than 2% per year.

- The federal government should require a background check before allowing anyone to buy a gun.

- Social media accounts should not be censored in any way.

A claim of policy can also look like a direct command, such as “So if you are an American citizen, don’t let anything stop you from voting.”

Note that not all claims of policy give details or specifics about what should be done or how. Sometimes an author is only trying to build momentum and point us in a certain direction. For example, “Schools must find a way to make bathrooms more private for everyone, not just transgender people.”

Claims of policy don’t have to be about dramatic actions. Even discussion, research, and writing are kinds of action. For example, “Americans need to learn more about other wealthy nations’ health care systems in order to see how much better things could be in America.”

Claims of Fact

Arguments do not always point toward action. Sometimes writers want us to share their vision of reality on a particular subject. They may want to paint a picture of how something happened, describe a trend, or convince us that something is bad or good.

In some cases, the writer may want to share a particular vision of what something is like, what effects something has, how something is changing, or of how something unfolded in the past. The argument might define a phenomenon, a trend, or a period of history.

Often these claims are simply presented as fact, and an uncritical reader may not see them as arguments at all. However, very often claims of fact are more controversial than they seem. For example, consider the claim, “Caffeine boosts performance.” Does it really? How much? How do we know? Performance at what kind of task? For everyone? Doesn’t it also have downsides? A writer could spend a book convincing us that caffeine really boosts performance and explaining exactly what they mean by those three words.

Some phrases writers might use to introduce a claim of fact include the following:

- Research suggests that _____________.

- The data indicate that _____________.

- _____________is increasing or decreasing.

- There is a trend toward _____________.

- _____________causes _____________

- _____________leads to _____________.

Often a claim of fact will be the basis for other claims about what we should do that look more like what we associate with the word “argument.” However, many pieces of writing in websites, magazines, office settings, and academic settings don’t try to move people toward action. They aim primarily at getting readers to agree with their view of what is fact. For example, it took many years of argument, research, and public messaging before most people accepted the claim that “Smoking causes cancer.”

Here are a few arguable sample claims of fact:

- It is easier to grow up biracial in Hawaii than in any other part of the United States.

- Raising the minimum wage will force many small businesses to lay off workers.

- Fires in the western United States have gotten worse primarily because of climate change.

- Antidepressants provide the most benefit when combined with talk therapy.

Claims of Value

In other cases, the writer is not just trying to convince us that something is a certain way or causes something, but is trying to evaluate the relative value or morality of something. They are rating it, trying to get us to share her assessment of its value. Think of a movie or book review or an Amazon or Yelp review. Even a “like” on Facebook or a thumbs up on a text message is a claim of value.

Claims of value are fairly easy to identify. Some phrases that indicate a claim of value include the following:

- _____________is terrible/disappointing/underwhelming.

- _____________is mediocre/average/decent/acceptable.

- We should celebrate _____________.

- _____________is great, wonderful, fantastic, impressive, makes a substantial contribution to _____________.

A claim of value can also make a comparison. It might assert that something is better than, worse than, or equal to something else. Some phrases that signal a comparative claim of value include these:

- _____________is the best _____________.

- _____________is the worst _____________.

- _____________is better than _____________.

- _____________is worse than _____________.

- _____________is just as good as _____________.

- _____________is just as bad as _____________

The following are examples of claims of value:

- The Bay Area is the best place to start a biotech career.

- Forest fires are becoming the worst threat to public health in California.

- Human rights are more important than border security.

- Experimenting with drag is the best way I’ve found to explore my feelings about masculinity and femininity.

- It was so rude when that lady asked you what race you are.

Note that the above arguments all include claims of fact but go beyond observing to praise or criticize what they are observing.[4]

Identifying the Main Claim

Now that we have this list of claims in the margin of the text, we know some of the things that the author wants us to believe. How do we sort them and put them in relation to each other? In this case, we found claims of policy, fact, and value, some of which were repeated in different parts of the argument. Which claim is the main point? How do other claims support this one?

We can try asking ourselves the following questions to see if we already have a sense of what the argument’s goal is.

- What does the writer want us to believe?

- What does the writer most want to convince us of?

- Where is the writer going with this?

- If the writer had to make their point in just one sentence, what would they say?

A good first place to look for the focus, of course, is the title. Often the title will declare the main claim outright. After examining how the title review the parts of the article where main ideas are expressed.

Here, the title question “Wouldn’t We All Cross the Border?” implies the answer “Yes.” We can look for the same idea in the text and check whether it seems to be the main one. The third paragraph describes why the author would cross the border and then generalizes to claim that others would do the same. At the start of the last paragraph, the writer declares that “ …most of us, under desperate circumstances, would cross the border without permission and feel no moral qualms about doing so.” Note that this is a claim of fact about what people would do and how they would feel about it.

Next, we can complete the following steps.

- Examine the topic sentence and main idea of each paragraph.

- Analyze the restatement of the main ideas in the conclusion.

When we review the other sections, we find several other claims of policy. Introductions set expectations, and here, the first paragraph alludes to public debates on immigration policy. It suggests that it may not be right to stop people from coming into America, and it may not be wrong to cross the border, even illegally. These early references to what is right suggest that the argument aims to do more than describe how people might feel under different circumstances. The argument is going to weigh in on what border policy should be. The second paragraph confirms this sense as it builds up to the still vague sentence, “ Surely there are ways to regulate the border without criminalizing people who are driven by need and good intentions.”

In the last paragraph, we learn what these ways might involve. Three different claims of policy emerge:

- “… We must recognize this crossing as an ethical, reasonable act.”

- “How can either a wall or a detention center be on the side of justice?” (The implication, of course, is that they cannot be.)

- “ We must find a policy that treats migrants as we would want to be treated–with empathy, respect, and offers of help.”

Arguments sometimes emphasize their main point in the very last sentence, in part to make it memorable. However, the end of the argument can also be a place for the author to go a little beyond their main point.

The phrase “empathy, respect, and offers of help” sounds important, but we should note that the rest of the argument isn’t about how to help migrants. However, the idea that we should respond more positively to migrants has recurred throughout. The idea that migrants are not in the wrong–that they are not criminals–is clearly key, and so is the idea that we should change border policy accordingly.

Here is one way, then, to combine those last two ideas into a summary of the overall claim of the argument:

Claim: Border policy should not criminalize undocumented immigrants.

Instructions

- Skim first, then read “Give Women a Chance in the Air” by Eve Garrett Brady, a feature article about Amelia Earhart published in Evening Star on September 22, 1929.

- As you skim, notice where the major claims are made throughout the article.

- Read the parts in detail that are focused on making claims.

- As you read, you may decide to make annotations in the margins.

- List at least 5 claims made throughout the article using the Claims Template:

- Identify the type of claim: policy, fact, or value

- Quote or summarize the claim

- Cite the paragraph where you found it

- Explain how it connects to the main claim.

- Based on the sub-claims identify the main claim.

Give Women a Chance in the Air, Pleads Amelia Earhart

Eternal Bogie of “Feminine Nerves” Long Since Dispelled, Asserts Famous Airwoman, and Fair Sex Entitled to More Opportunity in the Sky.

.

BY EVE GARRETTE GRADY

THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C., SEPTEMBER 22, 1929.

ARE women being discriminated against in aviation? Is society pushing men forward and holding women back in the great modern conquest of the air? Miss Amelia Earhart, the first woman to fly the Atlantic and perhaps best qualified to speak authoritatively in behalf of her sex, says emphatically that they are. Despite the fact that women are rapidly overcoming the inbred timidities which civilization has imposed upon them, despite their widespread interest in flying and the future it holds for them, they are still bound by the chains of artificial difference between the sexes. She says, “Women can qualify in the air as in any other sport. Their influence and approval are vital to the success of commercial aviation. Women and girls write to me by the thousands to learn the truth about aviation and what women’s chances are. There is nothing in woman’s make-up which would make her inferior to a man as an air pilot. The only barrier to her swift success is her lack of opportunity to receive proper training.

“Society has imposed unjust distinctions in the education of the sexes. Regardless of a woman’s natural inclinations and talents, she has been assigned summarily to certain prescribed courses of study in public and private schools. Sewing and domestic science are made compulsory for schoolgirls whose propensities are wholly in the direction of things mechanical. Women have an abysmal ignorance of mechanics and engineering through no fault of their own. However, the importance which mechanical labor-saving devices have assumed in the average American home is beginning to open the eyes of even the most helplessly feminine woman. She is beginning to realize that to keep in tune with the march of modem progress she must have some very definite mechanical knowledge.”

“She realizes that it is important to her comfort, her efficiency as a worker and a buyer that she learn what makes the wheels go round. It is my firm belief that the woman’s interest in aviation—backed by the strong opinions of an air-minded generation of school-girls—will bring this question of unfair and unjust discrimination between the sexes as regards education with reference to vocational aptitude directly into the open and definitely burn away fallacious barriers.”

Miss Earhart strode up and down the office, her hands boyishly thrust deep in the pockets of her trim tweed suit. I had found her at the trophy-cluttered desk of her publisher, George Palmer Putnam, performing one of the duties of a celebrity and an author, reading huge piles of fan mail.

The aviatrix is tall and slender and wears clothes with distinction. She has the unaffected simplicity of a real person and a disarming, friendly smile. She prefers a coat of tan and a few freckles to rouge and lipstick. One hates to be banal, particularly since her praises have been sung from coast to coast, but it must be set down as my firm conviction that no description of Amelia Earhart is adequate without the statement that she represents that which we like to think of as best and truest in our women. In other words, America’s “first woman flyer” is the real thing.

“Commercial aviation is a bustling industry, but at present it is making little or no effort to enable women to secure the training and experience required of an Industrial pilot on one of the regular airways,” she said. “The Army and Navy training schools, which are among the best, are, of course, closed to women. Some of the large transportation companies conduct their own schools for pilots. They are excellent, but there, too, women are barred.

“Sooner or later the big air lines must enlist women’s intelligent co-operation, because without them aviation cannot hope for success. One has only to study the history of the automobile industry to recognize the truth of what I am saying.”

“Twenty years ago the idea that woman could learn to drive automobiles was considered preposterous. The eternal bogies, feminine nerves and physical weakness, were advanced as final and conclusive arguments when all others failed. And strangely enough, today, in the face of superlative proof to the contrary, one sees these same threadbare, bromidic arguments solemnly dusted off and brought forth again to be used against woman aviators.” Miss Earhart smiled. “I doubt if men will ever believe that there is no such thing as feminine nerves as opposed to nerves of the masculine variety. Yet, If anything, virtually all of woman’s experience and training has been of the sort to give her nerves of iron. No man could endure for a half hour what is just part of a day’s work to a woman—cooking a dinner with one hand, rocking a cradle with the other, at the same time keeping a watchful eye on sonny and sister, who are probably very much underfoot. Certainly, the performance of young business women in our great cities is a daily tribute to their ability to thrive under the tension of noise, big business and high-pressure work.”

Miss Earhart has noted a growing interest in aviation on the part of sportswomen throughout America. “The woman who likes to play a good game of golf or enjoys riding to the hounds has found flying one of the most enthralling of all sports. Now that manufacturers are marketing little sport planes with light engines—particularly easy for a woman to handle—aviation country clubs are springing up everywhere. It is only a question of time until woman golf teams will adopt travel by air from one country club to another for competitive matches as a matter of course. It should prove to be a highly advantageous mode of traveling for tournament players, because it is diverting and relieves the player of a great deal of the last-minute tension and nervousness which transportation by train or automobile aggravates.”

“Since the opening of the Transcontinental Air Transport Service, traveling by plane has begun to have a tremendous vogue among women. The cleanliness of traveling by plane instantly appeals to them —no dirt, no cinders, no mussy, disheveled clothes. Women are innately fastidious, you know. They are also attracted by the friendliness of air traveling. Plane passengers consider that they have a common bond of experience. They waive the customary formalities of the more earthy means of transportation, it all becomes much more interesting; at least, the women think so.”

“The fact that air transportation is the swiftest is also beginning to have as much weight with women as with men. A number of smart women on the West coast find that by slipping off to New York by airplane, they not only steal a march by being the first to appear with the news of the latest Fall fashions, but the novelty of being an ‘air shopper’ has its practical advantages. Of course, movie people who are obliged almost to commute from coast to coast consider the transcontinental air service an answer to their prayers.”

“Many women feel, and quite rightly, that they are advancing world progress by confining their efforts to aviation’s fringes. Although many of them have never been in an airplane—many say they wouldn’t be paid to enter one—still they are turning their hands to the task of making landing fields more attractive—most of them are extremely barren, If not actually unsightly—and, what is more important, working out air-road marks for flyers. It is nice when one is flying 100 miles an hour over strange country to know the names of the different towns and cities over which one hovers. A number of women’s clubs have done excellent work in this respect I cannot praise too highly one club where the women themselves got out and painted the name of their town on one of its buildings in huge bright letters as a guide and greeting to flyers.”

“I think there is no doubt about the average schoolgirl being air-minded. I receive so many letters from girls of 15 who bewail the fact that they are obliged to bootleg their airplane rides because their parents forbid them to go up. Although I cannot exactly commend it, their conduct shows a very definite trend. Many of them say they want to make aviation their ‘life work.’ All are anxious and willing to study to prepare themselves to be expert flyers. Still, I regret to say, they are being retarded, held back. But the pendulum is swinging. Women are determined to be an integral part of aviation. Speed the day when the announcement is made of the first aviation training school ‘exclusively for girls.’”

Born in Atchison, Kansas, Amelia Earhart lived there until she reached high school age. When the United States entered the World War she was at Ogontz School, in the suburbs of Philadelphia. Her sympathies were aroused by seeing four soldiers on crutches while she was visiting her sister in Toronto. She dropped school and started training under the Canadian Red Cross. Her first assignment was at Spadina Military Hospital. At the end of her hospital career Miss Earhart Joined her father and mother in Los Angeles. It was in California that she first became actively Interested in aviation. In 1920 she established the woman’s record for altitude. She holds the first international pilot’s license issued to a woman.

After some time in California, Miss Earhart decided to return to the East. She sold her plane for a ear. After a Summer at Harvard, she joined her sister in teaching and doing settlement work in Boston. Her Interest was soon reawakened in aviation and she became a member of the Boston chapter of the National Aeronautical Association and was ultimately made vice president. After her return from the transatlantic trip she was made president—the first woman president of a body of the N.A.A.

Until her epoch-making flight. Miss Earhart continued as a worker at Dennison House, Boston’s second oldest settlement. At present, Miss Earhart lives in New York. That is, when she is not flying about the country as assistant to the general traffic manager of Transcontinental Air Transport, with which organization Col. Charles A. Lindbergh is also associated. She is also aviation editor of a monthly magazine.

It is characteristic of her that in her book, “20 Hrs. 40 Min.” which tells the Intimate story of her flight across the Atlantic in the Friendship, that she should say time and time again throughout the narrative that the entire credit of the magnificent exploit should go to Wilmer Stultz and Louis Gordon, the men who piloted her.

Not long ago, Miss Earhart explored the bottom of the ocean off Block Island as a deep-sea diver. The first time she went down her diving suit leaked, but, nothing daunted, she

made another try the next day. When she came up, after being down more than 20 minutes, she said: “It is nothing at all. Plenty of women have been deeper and stayed longer.”

(Copyright, 1929.)

Assignment: Claims Template

| Main Claim | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Claim (Policy, Fact, or Value) | Quote/summary of claim from “Give Women a Chance in the Air” | Paragraph # | How is it connected to the main claim? |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

Media Attributions

- Scarecrow_(6328014509) © Mohd. Farid is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Notes on claims © Anna Mills is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Amelia-in-evening-clothes_(cropped) © Unknown author is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1929_Women’s_National_Air_Derby © Anonymous; SDASM Archives is licensed under a Public Domain license

- DeVries, K.,Browning, E., Boylan, K., Burton, K., & Kurtz, J. (2018). Let's Get Writing. Virginia Western Educational Foundation, Inc. https://pressbooks.pub/vwcceng111/chapter/chapter-3-argument/ ↵

- Mills, A. (2025). How Arguments Work. UC Davis. https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Composition/Advanced_Composition/How_Arguments_Work_-_A_Guide_to_Writing_and_Analyzing_Texts_in_College_(Mills)/00%3A_Front_Matter/01%3A_TitlePage. ↵

- Mills, A. (2025). How Arguments Work. UC Davis. https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Composition/Advanced_Composition/How_Arguments_Work_-_A_Guide_to_Writing_and_Analyzing_Texts_in_College_(Mills)/00%3A_Front_Matter/01%3A_TitlePage. ↵

- Mills, A. (2025). How Arguments Work. UC Davis. https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Composition/Advanced_Composition/How_Arguments_Work_-_A_Guide_to_Writing_and_Analyzing_Texts_in_College_(Mills)/00%3A_Front_Matter/01%3A_TitlePage. ↵

- Mills, A. (2025). How Arguments Work. UC Davis. https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Composition/Advanced_Composition/How_Arguments_Work_-_A_Guide_to_Writing_and_Analyzing_Texts_in_College_(Mills)/00%3A_Front_Matter/01%3A_TitlePage. ↵

- Garrett Grady, E. (1929, September 22). Give Women a Chance in the Air, Pleads Amelia Earhart. The Sunday Star, 6. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1929-09-22/ed-1/seq-102/#date1=1928&index=13&rows=20&words=Amelia+Earhart&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=&date2=1932&proxtext=Amelia+Earhart&y=15&x=17&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1&loclr=blogser. ↵