7.1 Rhetorical Analysis

Erin Thomas, MFA

What is Rhetorical Analysis?

Simply defined, rhetoric is the art or method of communicating effectively to an audience, usually with the intention to persuade; thus, rhetorical analysis means analyzing how effectively writers or speakers communicate their messages or arguments to an audience. [1]

Through rhetorical analysis, readers, viewers, and listeners evaluate the effectiveness of messages. Messages are not only written texts, but include speeches, films, photographs, memes, social media posts, and advertisements. Essentially, a message is any human creation that conveys cultural information. A sculpture is a message; a dance routine is also a message.

Since this is a reading class, we are primarily evaluating written messages, which require you to read critically. Reading critically entails more than being impacted by a piece of writing. It refers to understanding the structure and content of the writing and how both of these convey meaning to and affect the audience. Critical reading does not mean that you are looking for what is wrong with a work. Instead, thinking critically means approaching a work as if you were a critic or commentator whose job it is to analyze a text beyond its surface. One of the first steps in this process is evaluating the author’s purpose. For example, does the author want to persuade, inspire, entertain, provoke humor, or simply inform the audience?

Without readers, a text doesn’t mean anything. Global classics like Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Cervante’s Don Quixote, and Arabian Nights are just ink on paper unless readers come along to make sense of the symbols on the pages. It’s the reading of the words that makes them meaningful and valuable. But, with complex texts like these, what they mean and exactly how they contribute to our understanding of life is not straightforward. It takes careful consideration of many of the text’s elements, including what we like to call the rhetorical situation.[2]

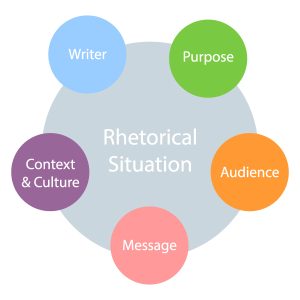

The Rhetorical Situation

The “rhetorical situation” is a term used to describe the context of in which a writer communicates, whether in written or oral form. To define a “rhetorical situation,” ask yourself this question: “who is talking to whom about what, how, and why?” Before analyzing a message, it is important to identify the the five main components of the rhetorical situation, which are listed below:

- Purpose

- Writer

- Audience

- Message

- Context/Culture

PURPOSE refers to the why an author is writing. The purpose is determined by what the writer wants the audience to do/think/decide/act as a result of reading the text.

WRITER refers to the biases, past experiences, and knowledge an author brings to the writing situation. These elements will influence how a writer crafts the message, whether positively or negatively. This examination also includes the writer’s role within society and position relative to the target audience.

AUDIENCE refers to the readers/listeners/viewers/users. Audience Analysis is possibly the most critical part of understanding the rhetorical situation as messages are crafted specifically to communicate with particular groups of people, often there is both a primary and secondary audience to a message.

MESSAGE refers to the information communicated, or the content within a text. The content should be aligned to the purpose and targeted to the audience in terms of content, style, and where and how it is presented.

CONTEXT refers to the situation that creates the need for the writing. In other words, what has happened or needs to happen that creates the need for communication? The context is influenced by timing, location, current events, and culture, which can be organizational or social.[3]

You can the questions in the Rhetorical Situation Critical Reading Questions table below to help you critically evaluate the rhetorical situation in a text or another type of message.

Rhetorical Situation Critical Reading Questions

| Purpose | Writer | Audience | Message | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Why did the writer create the message: to persuade, inform, manipulate, sell, or entertain? | 1. What is the writer’s background? 2. What is the writer’s educational or experiential expertise in the topic? 3. What is the writer’s role within society and how does this relate to the audience? 4. What is the writer’s bias? |

1. What are the demographics of the target audience (age, gender, economic level, nationality, political agenda)? 2. What is the primary/ secondary audience? 3. How will the audience react to the message? |

1. How can the message be accessed (hardcopy vs. electronically public vs. behind a pay wall). 2. What is the content of the message? 3. How is it structured? 4. What kind of message is it (blog, ad, post, essay, poem, novel, news article)? |

1. What circumstance prompted the writer to create the message? 2. How does it relate to current/ historical events? 3. How does it reflect its cultural moment? 4. How does it respond to other messages? |

The Rhetorical Situation and You

To understand how you use the rhetorical situation to evaluate messages every day, read the following excerpt from Backpacks vs. Briefcases: Steps toward Rhetorical Analysis by Laura Bolin Carroll.

Laura Bolin Carroll

First Impressions

Imagine the first day of class in first year composition at your university. The moment your professor walked in the room, you likely began analyzing her and making assumptions about what kind of teacher she will be. You might have noticed what kind of bag she is carrying—a tattered leather satchel? a hot pink polka-dotted backpack? a burgundy brief case? You probably also noticed what she is wearing—trendy slacks and an untucked striped shirt? a skirted suit? jeans and a tee shirt?

It is likely that the above observations were only a few of the observations you made as your professor walked in the room. You might have also noticed her shoes, her jewelry, whether she wears a wedding ring, how her hair is styled, whether she stands tall or slumps, how quickly she walks, or maybe even if her nails are done. If you don’t tend to notice any of these things about your professors, you certainly do about the people around you—your roommate, others in your residence hall, students you are assigned to work with in groups, or a prospective date. For most of us, many of the people we encounter in a given day are subject to this kind of quick analysis.

Now as you performed this kind of analysis, you likely didn’t walk through each of these questions one by one, write out the answer, and add up the responses to see what kind of person you are interacting with. Instead, you quickly took in the information and made an informed, and likely somewhat accurate, decision about that person. Over the years, as you have interacted with others, you have built a mental database that you can draw on to make conclusions about what a person’s looks tell you about their personality. You have become able to analyze quickly what people are saying about themselves through the way they choose to dress, accessorize, or wear their hair.

We have, of course, heard that you “can’t judge a book by its cover,” but, in fact, we do it all the time. Daily we find ourselves in situations where we are forced to make snap judgments. Each day we meet different people, encounter unfamiliar situations, and see media that asks us to do, think, buy, and act in all sorts of ways. In fact, our saturation in media and its images is one of the reasons why learning to do rhetorical analysis is so important. The more we know about how to analyze situations and draw informed conclusions, the better we can become about making savvy judgments about the people, situations and media we encounter.

Implications of Rhetorical Analysis

Media is one of the most important places where this kind of analysis needs to happen. Rhetoric—the way we use language and images to persuade—is what makes media work. Think of all the media you see and hear every day: Twitter, television shows, web pages, billboards, text messages, podcasts. Even as you read this chapter, more ways to get those messages to you quickly and in a persuasive manner are being developed. Media is constantly asking you to buy something, act in some way, believe something to be true, or interact with others in a specific manner. Understanding rhetorical messages is essential to help us to become informed consumers, but it also helps evaluate the ethics of messages, how they affect us personally, and how they affect society. Take, for example, a commercial for men’s deodorant that tells you that you’ll be irresistible to women if you use their product. This campaign doesn’t just ask you to buy the product, though. It also asks you to trust the company’s credibility, or ethos, and to believe the messages they send about how men and women interact, about sexuality, and about what constitutes a healthy body. You have to decide whether or not you will choose to buy the product and how you will choose to respond to the messages that the commercial sends.

Or, in another situation, a Facebook group asks you to support health care reform. The rhetoric in this group uses people’s stories of their struggles to obtain affordable health care. These stories, which are often heart-wrenching, use emotion to persuade you—also called pathos. You are asked to believe that health care reform is necessary and urgent, and you are asked to act on these beliefs by calling your congresspersons and asking them to support the reforms as well.

Because media rhetoric surrounds us, it is important to understand how rhetoric works. If we refuse to stop and think about how and why it persuades us, we can become mindless consumers who buy into arguments about what makes us value ourselves and what makes us happy. For example, research has shown that only 2% of women consider themselves beautiful (“Campaign”), which has been linked to the way that the fashion industry defines beauty. We are also told by the media that buying more stuff can make us happy, but historical sur- veys show that US happiness peaked in the 1950s, when people saw as many advertisements in their lifetime as the average American sees in one year (Leonard).

Our worlds are full of these kinds of social influences. As we interact with other people and with media, we are continually creating and interpreting rhetoric. In the same way that you decide how to process, analyze or ignore these messages, you create them. You probably think about what your clothing will communicate as you go to a job interview or get ready for a date. You are also using rhetoric when you try to persuade your parents to send you money or your friends to see the movie that interests you. When you post to your blog or tweet you are using rhetoric. In fact, according to rhetorician Kenneth Burke, rhetoric is everywhere: “wherever there is persuasion, there is rhetoric. And wherever there is ‘meaning,’ there is ‘persuasion.’ Food eaten and digested is not rhetoric. But in the meaning of food there is much rhetoric, the meaning being persuasive enough for the idea of food to be used, like the ideas of religion, as a rhetorical device of statesmen” (71–72). In other words, most of our actions are persuasive in nature. What we choose to wear (tennis shoes vs. flip flops), where we shop (Whole Foods Market vs. Wal-Mart), what we eat (organic vs. fast food), or even the way we send information (snail mail vs. text message) can work to persuade others.

Chances are you have grown up learning to interpret and analyze these types of rhetoric. They become so commonplace that we don’t realize how often and how quickly we are able to perform this kind of rhetorical analysis. When your teacher walked in on the first day of class, you probably didn’t think to yourself, “I think I’ll do some rhetorical analysis on her clothing and draw some conclusions about what kind of personality she might have and whether I think I’ll like her.” And, yet, you probably were able to come up with some conclusions based on the evidence you had.

However, when this same teacher hands you an advertisement, photograph or article and asks you to write a rhetorical analysis of it, you might have been baffled or felt a little overwhelmed. The good news is that many of the analytical processes that you already use to interpret the rhetoric around you are the same ones that you’ll use for these assignments.[4]

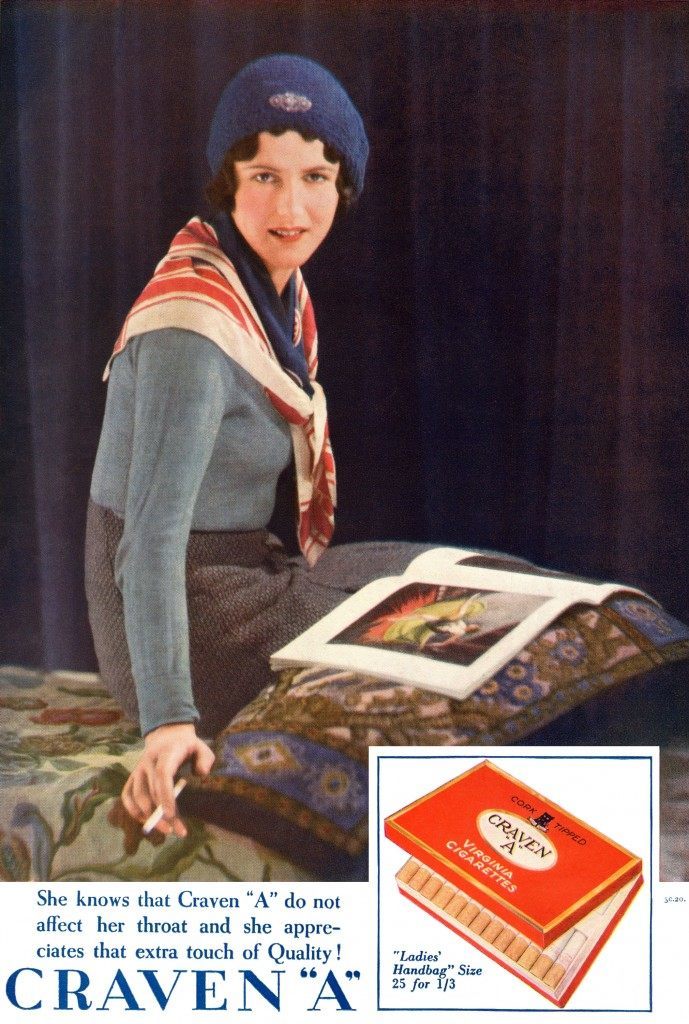

In this next assignment you will use the rhetorical situation to examine three smoking ads from the 1930s using the rhetorical situation. This is a preliminary exercise to prepare you to use rhetorical analysis to examine a text. As Laura Bolin Carroll suggests, don’t be nervous. You are a pro at this already.

Instructions

- First, answer the following questions from Backpacks and Briefcases:

- According to the text, what are common situations in which we interpret messages on a daily basis?

- What are two ways that you create messages?

- Second, Use the Rhetorical Situation Template to evaluate the two smoking ads below.

- Carefully consider each of questions for each ad.

- You may notice that both of the ads mention throat irritation. For more information about the historical context of these ads, enter: smoking, ads, 1930’s, and throat irritation into Google to get an AI Overview of the historical context. If you are unable to access this information, consider the sample AI overview below. You may also decide to skim and scan other sources that come up in your search to get a better understanding of the context.

- Using your research on the historical background to provide context, fill out the table below. If you don’t have enough context to answer the questions, use the information in the image to search for more information on the web. For example, you may decide to search for more information on the cigarette brands featured in the ads.

Historical Context: Gemini Overview

Tobacco Industry Marketing and Throat Irritation:

- Promoting “Less Irritating” Cigarettes: Brands like Lucky Strike ran campaigns claiming their cigarettes were “less irritating” to the throat, often citing physician endorsements to back their claims, despite lacking scientific evidence.

- Focusing on “Mildness” and “Non-irritating”: Companies marketed cigarettes as “nonirritating” and “mild” to address concerns about throat discomfort.

- Using Doctors in Advertisements: Tobacco advertisements frequently depicted doctors, including “throat doctors,” to suggest their product’s safety and effectiveness, creating a false image of tobacco safety.

- Introducing Menthol and Filtered Cigarettes: Menthol and filtered cigarettes emerged in the 1930s, with ads promoting their ability to prevent or relieve coughing, throat irritation, and “tongue bite”.

Medical Understanding of Throat Problems from Smoking:

- Growing Concerns: While the full extent of smoking’s dangers was not widely known, the discomforts associated with smoking, such as coughing, prompted some public anxiety and led some people to question the safety of cigarettes.

- Early Research: Some early scientific studies began to point to a link between smoking and health problems. For example, a 1929 study linked lung cancer to smoking, and subsequent research in the 1930s confirmed the connection. However, this research did not immediately translate into widespread public knowledge about the long-term dangers of smoking.

Type your textbox content here.[5]

Ad 1

Ad 2

Assignment: Rhetorical Situation Template

| Rhetorical Situation | Purpose | Writer | Audience | Message | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questions | Why did the writer create the message: to persuade, inform, manipulate, sell, or entertain? | 1. What is the writer’s background? 2. What is the writer’s educational or experiential expertise in the topic? 3. What is the writer’s role within society and how does this relate to the audience? 4. What is the writer’s bias? |

1. What are the demographics of the target audience (age, gender, economic level, nationality, political agenda)? 2. What is the primary/ secondary audience? 3. How will the audience react to the message? |

1. How can the message be accessed (hardcopy vs. electronically public vs. behind a pay wall). 2. What is the content of the message? 3. How is it structured? 4. What kind of message is it (blog, ad, post, essay, poem, novel, news article)? |

1. What circumstance prompted the writer to create the message? 2. How does it relate to current/ historical events? 3. How does it reflect its cultural moment? 4. How does it respond to other messages? |

| Ad 1 |

|

||||

| Ad 2 |

|

Media Attributions

- Rhetorical Situation © Suzan Last is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Craven-A-ad-from-1930-689×1024 © Unknown Author is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bizarre Tobacco Advertising (2) © clotho98 is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Browning, E., Boylan, K., Burton, K., DeVries, K., & Kurtz, J. (2018). Let's Get Writing. Virginia Western Educational Foundation, Inc. https://pressbooks.pub/vwcceng111/chapter/chapter-2-rhetorical-analysis/ ↵

- Richardson, G. (2019). The Reading Handbook. MHCC Library Press. https://open.ocolearnok.org/woscreadinghandbook/chapter/figurative-language/ ↵

- Last, S. (2022). Technical Writing Essentials (H5P ed.). University of Victoria. https://opentextbc.ca/technicalwritingh5p/ ↵

- Backpacks vs Briefcases: Steps Toward Rhetorical Analysis.Authored by: Laura Bolin Carroll. Provided by: Writing Spaces.Located at: http://writingspaces.org/sites/default/files/carroll–backpacks-vs-briefcases.pdf.License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike ↵

- Google. (2024, July 4). Gemini [Large language model]https://gemini.google.com/app ↵