5.2 Inferring Words Using Affixes and Roots

Rachel Cox-Vineiz, MA

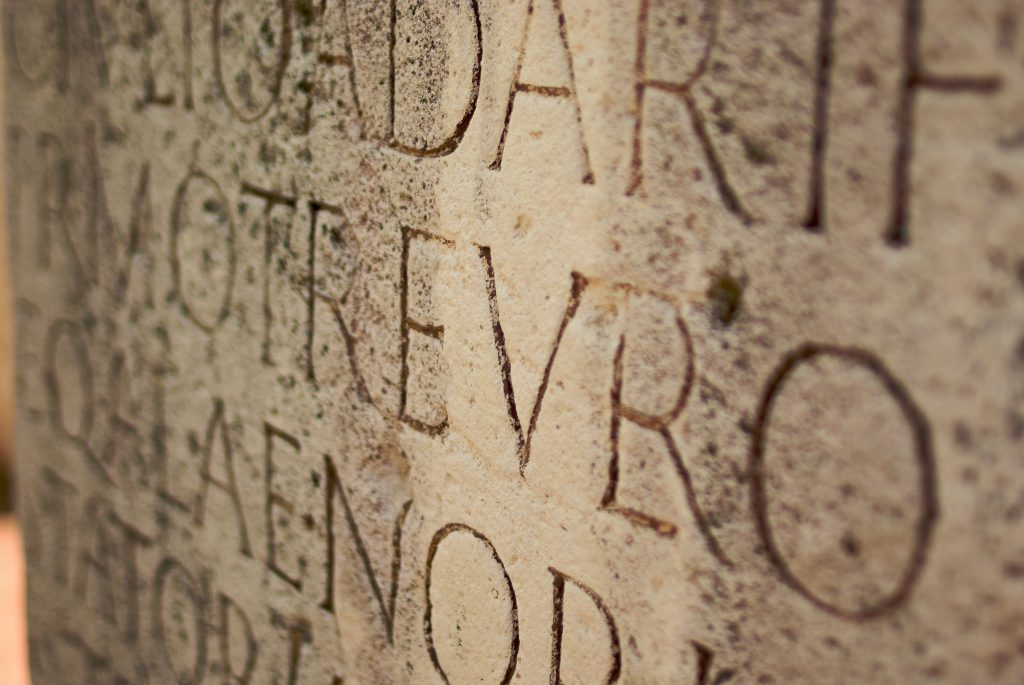

Word Roots & Affixes: Unlocking the Power of Latinates

One of the most powerful ways to build your vocabulary and strengthen your reading comprehension is to understand how words are put together. Words are made up of morphemes, which are the smallest parts of a word that carry meaning. These include roots, prefixes, and suffixes.

Root Words

A root word holds the basic meaning of a word. Sometimes a root word can stand alone — these are called base words — while others, called bound morphemes, need prefixes or suffixes to form a complete word. For example, the word legal can stand alone, meaning “permissible by law.” When you add prefixes and suffixes, you can create new words like illegal or legalize, all connecting back to the idea of law. In contrast, a bound root like ject (which means “to throw”) cannot stand alone. But combined with affixes, it forms words like eject, reject, and interject.

English has a long history of borrowing words from other languages. In particular, many English roots come from Latin and Greek. Even though spelling and pronunciation have changed over time, the core meanings remain. For instance, the Latin root aqua (meaning “water”) is the base for words like aquarium and aquatic.

Sometimes a root word changes slightly when it appears in a new form. For example, the root words describe and noise look different when they appear in description and noisy. These changes happen because certain sounds fit better with specific prefixes or suffixes, or simply because the language has evolved naturally over time.

Table 5.2.1: Examples of Roots

| Root | Meaning | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| civ | citizen, settled | civil, civilization, civic, uncivilized |

| friend | friend | friendly, unfriendly, friendship, befriend |

| doc | to teach | document, indoctrinate, doctor, documentary |

| val | worth, health, strength | value, evaluate, valor, valid |

| terr | earth, land | terrain, extraterrestrial, subterranean, territory |

| port | carry | transportation, portable, import/export, portal |

| gen | birth, race, produce | general, gender, generate, genre, generic |

| cycle | circle | bicycle, motorcyclist, cyclical, cyclist |

Affixes: Prefixes and Suffixes

In addition to roots, English words often include prefixes and suffixes. However, not every word contains a prefix or a suffix.

Prefixes are affixes that come at the beginning of a word and usually change its meaning. For example, adding dis- or un- to a word makes it negative: disbelief means “not belief,” and uncertain means “not certain.” Not every word has a prefix, and sometimes what looks like a prefix isn’t one. In the word internal, for instance, “inter” is part of the root and not a prefix meaning “between.”

Suffixes are affixes that are added to the end of a word and often change its part of speech or its tense. For example, the verb act becomes the noun action with the suffix -ion, and beautiful becomes beautifully with -ly. Some words have no suffix, some have one or more, and some include both prefixes and suffixes. A word can even have multiple prefixes (in/sub/ordination) or multiple suffixes (beautiful/ly).

It’s also important to remember that words can change spelling when combining roots and suffixes, and sometimes what appears to be a familiar prefix or root does not carry its usual meaning. For example, in the word missile, “mis” is not the prefix meaning “wrong.”

Learning to identify and understand roots, prefixes, and suffixes helps you decode unfamiliar words, improve your vocabulary, and become a more confident reader and writer. Once you start noticing these parts, you’ll be amazed at how many connections you can make — and how much easier it becomes to understand and remember new words.

Instructions

Assignment 1

Instructions: Read the following passage from “The Origins Great Depression” in The American Yawp. Use the prefix, root, and suffix information to guess the meanings of the underlined words. Remember that not every word will have a prefix or a suffix.

On Thursday, October 24, 1929, stock market prices suddenly plummeted. Ten billion dollars in investments (roughly equivalent to about $100 billion today) disappeared in a matter of hours. Panicked selling set in, stock values sank to sudden lows, and stunned investors crowded the New York Stock Exchange demanding answers. Leading bankers met privately at the offices of J. P. Morgan and raised millions in personal and institutional contributions to halt the slide. They marched across the street and ceremoniously bought stocks at inflated prices. The market temporarily stabilized but fears spread over the weekend and the following week frightened investors dumped their portfolios to avoid further losses. On October 29, Black Tuesday, the stock market began its long precipitous fall. Stock values evaporated. Shares of U.S. Steel dropped from $262 to $22. General Motors stock fell from $73 a share to $8. Four fifths of J. D. Rockefeller’s fortune—the greatest in American history—vanished.

Although the crash stunned the nation, it exposed the deeper, underlying problems with the American economy in the 1920s. The stock market’s popularity grew throughout the decade, but only 2.5 percent of Americans had brokerage accounts; the overwhelming majority of Americans had no direct personal stake in Wall Street. The stock market’s collapse, no matter how dramatic, did not by itself depress the American economy. Instead, the crash exposed a great number of factors that, when combined with the financial panic, sank the American economy into the greatest of all economic crises. Rising inequality, declining demand, rural collapse, overextended investors, and the bursting of speculative bubbles all conspired to plunge the nation into the Great Depression.

Despite resistance by Progressives, the vast gap between rich and poor accelerated throughout the early twentieth century. In the aggregate, Americans were better off in 1929 than in 1920. Per capita income had risen 10 percent for all Americans, but 75 percent for the nation’s wealthiest citizens. The return of conservative politics in the 1920s reinforced federal fiscal policies that exacerbated the divide: low corporate and personal taxes, easy credit, and depressed interest rates overwhelmingly favored wealthy investors who, flush with cash, spent their money on luxury goods and speculative investments in the rapidly rising stock market.

The pro-business policies of the 1920s were designed for an American economy built on the production and consumption of durable goods. Yet by the late 1920s, much of the market was saturated. The boom of automobile manufacturing, the great driver of the American economy in the 1920s, slowed as fewer and fewer Americans with the means to purchase a car had not already done so. More and more, the well-to-do had no need for the new automobiles, radios, and other consumer goods that fueled gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the 1920s. When products failed to sell, inventories piled up, manufacturers scaled back production, and companies fired workers, stripping potential consumers of cash, blunting demand for consumer goods, and replicating the downward economic cycle. The situation was only compounded by increased automation and rising efficiency in American factories. Despite impressive overall growth throughout the 1920s, unemployment hovered around 7 percent throughout the decade, suppressing purchasing power for a great swath of potential consumers.

For American farmers, meanwhile, hard times began long before the markets crashed. In 1920 and 1921, after several years of larger-than-average profits, farm prices in the South and West continued their long decline, plummeting as production climbed and domestic and international demand for cotton, foodstuffs, and other agricultural products stalled. Widespread soil exhaustion on western farms only compounded the problem. Farmers found themselves unable to make payments on loans taken out during the good years, and banks in agricultural areas tightened credit in response. By 1929, farm families were overextended, in no shape to make up for declining consumption, and in a precarious economic position even before the Depression wrecked the global economy.

Despite serious foundational problems in the industrial and agricultural economy, most Americans in 1929 and 1930 still believed the economy would bounce back. In 1930, amid one of the Depression’s many false hopes, President Herbert Hoover reassured an audience that “the depression is over.” But the president was not simply guilty of false optimism. Hoover made many mistakes. During his 1928 election campaign, Hoover promoted higher tariffs as a means for encouraging domestic consumption and protecting American farmers from foreign competition. Spurred by the ongoing agricultural depression, Hoover signed into law the highest tariff in American history, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, just as global markets began to crumble. Other countries responded in kind, tariff walls rose across the globe, and international trade ground to a halt. Between 1929 and 1932, international trade dropped from $36 billion to only $12 billion. American exports fell by 78 percent. Combined with overproduction and declining domestic consumption, the tariff exacerbated the world’s economic collapse.

This page titled 23.9: The Origins of the Great Depression is shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by American YAWP (Stanford University Press) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.

Assignment: Root and Affix Template

| Word | Prefix | Root | Suffix | Guess the Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ex. deportation | de- (remove, away) | -port- (carry, bear) | -ation (act of) | to remove |

| institutional | in- (in, on) | -stitut- (set up, place) | -ional (relating to) | |

| contributions | con- (with, together) | -tribut- (give, assign) | -ions (act or result of) | |

| precipitous | pre- (before) | -cip- (head, cast down) | -itous (full of) | |

| speculative | specul- (look, see) | -ate (cause to be) | -ive (tending to) | |

| conspired | con- (with, together) | -spir- (breathe) | -ed (past tense) | |

| resistance | re- (back, again) | -sist- (stand) | -ance (state of being) | |

| accelerated | ac- (to, toward) | -celer- (swift, speed) | -ated (past tense, cause to be) | |

| per capita | per- (through, for each) | -capita (head) | N/A | |

| exacerbated | ex- (out, thoroughly) | -acerb- (harsh, bitter) | -ated (past tense, cause to be) | |

| consumption | con- (with, together) | -sumpt- (take, take up) | -ion (act or result of) | |

| saturated | satur- (full, enough) | -ate (cause to be) | -ed (past tense) | |

| domestic | dom- (house) | -est- (related to) | -ic (relating to) | |

| production | pro- (forward) | -duct- (lead) | -ion (act or result of) | |

| replicating | re- (again, back) | -plic- (fold, bend) | -ating (present participle, action) | |

| automation | N/A | automat- (self-acting) | -ion (act or result of) | |

| agricultural | agri- (field, land) | -cult- (till, grow) | -ural (relating to) | |

| compounded | com- (together, with) | -pound- (put, place) | -ed (past tense) | |

| overextended | over- (too much, above) | -extend- (stretch out) | -ed (past tense) | |

| foundational | found- (bottom, base) | -ation (act or state of) | -al (relating to) | |

| competition | com- (together, with) | -pet- (seek, strive) | -ition (act or state of) |

Assignment 2

Instructions: Read the following passage from “Lived Experience of the Great Depression” and “Migration and the Great Depression” in The American Yawp. Use the prefix, root, and suffix information to guess the meanings of the underlined words. Remember that not every word will have a prefix or a suffix.

With rampant unemployment and declining wages, Americans slashed expenses. The fortunate could survive by simply deferring vacations and regular consumer purchases. Middle- and working-class Americans might rely on disappearing credit at neighborhood stores, default on utility bills, or skip meals. Those who could borrowed from relatives or took in boarders in homes or “doubled up” in tenements. The most desperate, the chronically unemployed, encamped on public or marginal lands in “Hoovervilles,” spontaneous shantytowns that dotted America’s cities, depending on bread lines and street-corner peddling. Poor women and young children entered the labor force, as they always had. The ideal of the “male breadwinner” was always a fiction for poor Americans, but the Depression decimated millions of new workers. The emotional and psychological shocks of unemployment and underemployment only added to the shocking material depravities of the Depression. Social workers and charity officials, for instance, often found the unemployed suffering from feelings of futility, anger, bitterness, confusion, and loss of pride. Such feelings affected the rural poor no less than the urban.

On the Great Plains, environmental catastrophe deepened America’s longstanding agricultural crisis and magnified the tragedy of the Depression. Beginning in 1932, severe droughts hit from Texas to the Dakotas and lasted until at least 1936. The droughts compounded years of agricultural mismanagement. To grow their crops, Plains farmers had plowed up natural ground cover that had taken ages to form over the surface of the dry Plains states. Relatively wet decades had protected them, but, during the early 1930s, without rain, the exposed fertile topsoil turned to dust, and without sod or windbreaks such as trees, rolling winds churned the dust into massive storms that blotted out the sky, choked settlers and livestock, and rained dirt not only across the region but as far east as Washington, D.C., New England, and ships on the Atlantic Ocean. The Dust Bowl, as the region became known, exposed all-too-late the need for conservation. The region’s farmers, already hit by years of foreclosures and declining commodity prices, were decimated. For many in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas who were “baked out, blown out, and broke,” their only hope was to travel west to California, whose rains still brought bountiful harvests and—potentially—jobs for farmworkers. It was an exodus. Oklahoma lost 440,000 people, or a full 18.4 percent of its 1930 population, to outmigration.

Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother became one of the most enduring images of the Dust Bowl and the ensuing westward exodus. Lange, a photographer for the Farm Security Administration, captured the image at a migrant farmworker camp in Nipomo, California, in 1936. In the photograph a young mother stares out with a worried, weary expression. She was a migrant, having left her home in Oklahoma to follow the crops to the Golden State. She took part in what many in the mid-1930s were beginning to recognize as a vast migration of families out of the southwestern Plains states. In the image she cradles an infant and supports two older children, who cling to her. Lange’s photo encapsulated the nation’s struggle. The subject of the photograph seemed used to hard work but down on her luck, and uncertain about what the future might hold.

The Okies, as such westward migrants were disparagingly called by their new neighbors, were the most visible group who were on the move during the Depression, lured by news and rumors of jobs in far-flung regions of the country. By 1932, sociologists were estimating that millions of men were on the roads and rails traveling the country. Economists sought to quantify the movement of families from the Plains. Popular magazines and newspapers were filled with stories of homeless boys and the veterans-turned- migrants of the Bonus Army commandeering boxcars. Popular culture, such as William Wellman’s 1933 film, Wild Boys of the Road, and, most famously, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939 and turned into a hit movie a year later, captured the Depression’s dislocated populations.

These years witnessed the first significant reversal in the flow of people between rural and urban areas. Thousands of city dwellers fled the jobless cities and moved to the country looking for work. As relief efforts floundered, many state and local officials threw up barriers to migration, making it difficult for newcomers to receive relief or find work. Some state legislatures made it a crime to bring poor migrants into the state and allowed local officials to deport migrants to neighboring states. In the winter of 1935–1936, California, Florida, and Colorado established “border blockades” to block poor migrants from their states and reduce competition with local residents for jobs. A billboard outside Tulsa, Oklahoma, informed potential migrants that there were “NO JOBS in California” and warned them to “KEEP Out.”

Sympathy for migrants, however, accelerated late in the Depression with the publication of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. The Joad family’s struggles drew attention to the plight of Depression-era migrants and, just a month after the nationwide release of the film version, Congress created the Select Committee to Investigate the Interstate Migration of Destitute Citizens. Starting in 1940, the committee held widely publicized hearings. But it was too late. Within a year of its founding, defense industries were already gearing up in the wake of the outbreak of World War II, and the “problem” of migration suddenly became a lack of migrants needed to fill war industries. Such relief was nowhere to be found in the 1930s.

Americans meanwhile feared foreign workers willing to work for even lower wages. The Saturday Evening Post warned that foreign immigrants, who were “compelled to accept employment on any terms and conditions offered,” would exacerbate the economic crisis. On September 8, 1930, the Hoover administration issued a press release on the administration of immigration laws “under existing conditions of unemployment.” Hoover instructed consular officers to scrutinize carefully the visa applications of those “likely to become public charges” and suggested that this might include denying visas to most, if not all, alien laborers and artisans. The crisis itself had stifled foreign immigration, but such restrictive and exclusionary actions in the first years of the Depression intensified its effects. The number of European visas issued fell roughly 60 percent while deportations dramatically increased. Between 1930 and 1932, fifty-four thousand people were deported. An additional forty-four thousand deportable aliens left “voluntarily.”

This page titled 23.12: The Lived Experience of the Great Depression is shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by American YAWP (Stanford University Press) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.

This page titled 23.13: Migration and the Great Depression is shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by American YAWP (Stanford University Press) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.

Assignment: Root and Affix Template

| Word | Prefix | Root | Suffix | Guess the Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ex. description | de- (down, away) | -script- (write) | -ion (act or result of) | Put something in words |

| tenements | N/A | tene- (hold, possess) | -ment (means or result of) + -s (plural) | |

| desperate | de- (away, undo) | -sper- (hope) | -ate (cause to be, full of) | |

| chronically | N/A | chron- (time) | -ic (relating to) + -ally (in a manner) | |

| psychological | N/A | psych- (mind) | -o- (connecting vowel) + -log- (study) + -ical (relating to) | |

| mismanagement | mis- (wrong, bad) | -manage- (control, handle) | -ment (means or result of) | |

| conservation | con- (with, together) | -serv- (keep, save) | -ation (act or process of) | |

| encapsulated | en- (in, on) | -capsul- (small box) | -ate (cause to be) + -d (past tense) | |

| photograph | photo- (light) | -graph- (write, draw) | N/A | |

| reversal | re- (back, again) | -vers- (turn) | -al (act of) | |

| legislatures | legis- (law) | -lat- (carry, bring) | -ure (act or result of) + -s (plural) | |

| competition | com- (with, together) | -pet- (seek, strive) | -ition (act or state of) | |

| accelerated | ac- (to, toward) | -celer- (swift, speed) | -ate (cause to be) + -d (past tense) | |

| restrictive | re- (back, again) | -strict- (draw tight) | -ive (tending to, doing) | |

| exclusionary | ex- (out, away from) | -clus- (shut, close) | -ionary (relating to) |

Assignment 3

Instructions: Read the following passage from “The Election of Franklin Roosevelt” in U.S. History by P. Scott Corbett. Use the prefix, root, and suffix information to guess the meanings of the underlined words. Remember that not every word will have a prefix or a suffix.

By the 1932 presidential election, Hoover’s popularity was at an all-time low. Despite his efforts to address the hardships that many Americans faced, his ineffectual response to the Great Depression left Americans angry and ready for change. Franklin Roosevelt, though born to wealth and educated at the best schools, offered the change people sought. His experience in politics had previously included a seat in the New York State legislature, a vice-presidential nomination, and a stint as governor of New York. During the latter, he introduced many state-level reforms that later formed the basis of his New Deal as well as worked with several advisors who later formed the Brains Trust that advised his federal agenda.

Roosevelt exuded confidence, which the American public desperately wished to see in their leader (Figure). And, despite his affluence, Americans felt that he could relate to their suffering due to his own physical hardships; he had been struck with polio a decade earlier and was essentially paralyzed from the waist down for the remainder of his life. Roosevelt understood that the public sympathized with his ailment; he likewise developed a genuine empathy for public suffering as a result of his illness. However, he never wanted to be photographed in his wheelchair or appear infirm in any way, for fear that the public’s sympathy would transform into concern over his physical ability to discharge the duties of the Oval Office.

Franklin Roosevelt brought a new feeling of optimism and possibility to a country that was beaten down by hardship. His enthusiasm was in counterpoint to Herbert Hoover’s discouraging last year in office.

Roosevelt also recognized the need to convey to the voting public that he was not simply another member of the political aristocracy. At a time when the country not only faced its most severe economic challenges to date, but Americans began to question some of the fundamental principles of capitalism and democracy, Roosevelt sought to show that he was different—that he could defy expectations—and through his actions could find creative solutions to address the nation’s problems while restoring public confidence in fundamental American values. As a result, he not only was the first presidential candidate to appear in person at a national political convention to accept his party’s nomination but also flew there through terrible weather from New York to Chicago in order to do so—a risky venture in what was still the early stages of flight as public transportation. At the Democratic National Convention in 1932, he coined the famous phrase: “I pledge myself to a new deal for the American people.” The New Deal did not yet exist, but to the American people, any positive and optimistic response to the Great Depression was a welcome one.

Excerpted from U.S. History by P. Scott Corbett, Ventura College Volker Janssen, California State University, Fullerton, John M. Lund, Keene State College, Todd Pfannestiel, Clarion University, Paul Vickery, Oral Roberts University, and Sylvie Waskiewicz. License: CC BY-NC

Assignment: Root and Affix Template

| Word | Prefix | Root | Suffix | Guess the Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ex. description | de- (down, away) | -script- (write) | -tion -ion (act or result of) | Put something in words |

| popularity | N/A | -popul- (people) | -arity (state or quality of) | |

| ineffectual | in- (not) + e- / ex- (out or from) | -fect- (do, make) | -ual (relating to) | |

| nomination | N/A | nomin- (name) | -ation (act or process of) | |

| sympathy | sym- (with, together) | -path- (feeling, suffering) | -y (state or quality) | |

| transform | trans- (across, beyond) | -form- (shape) | N/A | |

| discharge | dis- (away, apart) | -charge- (load, burden) | N/A | |

| counterpoint | counter- (against, opposing) | -point- (prick, dot) | N/A | |

| convey | con- (with, together) | -vey (carry, way) | N/A | |

| capitalism | N/A | capit- (head, chief) | -al (relating to) + -ism (doctrine, system | |

| democracy | N/A | demo- (people) | -cracy (rule, government) | |

| fundamental | N/A | fund- (bottom, base) | -a- (connecting vowel) + -ment (result, product) + -al (relating to) | |

| transportation | trans- (across, beyond) | -port- (carry) | -ation (act or process of) |

Media Attributions

- Latin_Letters © Tfioreze is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U.S. History, Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1941, The Rise of Franklin Roosevelt. (n.d.). OER Commons. Retrieved August 8, 2025, from https://oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/15531/overview ↵