Step 1: Determine Program Needs

Before you start searching for a horse to acquire, you must determine what type of horse your program needs, as not every horse will be a good fit for your program. The first step is to create a detailed list of needs and wants to reference as you search. This list will help you stay focused on your goal of finding a suitable lesson horse. This will save you and the sellers time as you are more readily able to weed out unsuitable horses.

To determine the ideal horse, there are many factors that you should consider including your current program offerings and future program goals. Knowing what the horse needs to do in your program will allow you to determine the traits you will and will not accept in a prospective horse. Additionally, you must consider your resources, including the time available, budget constraints, and staff capabilities. Before diving into the specifics of horse traits and how they influence selection, it is essential to define your program’s goals and characteristics.

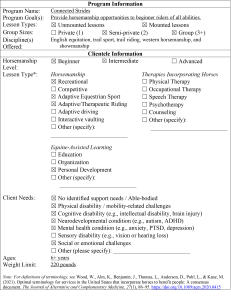

Start by filling out the Program Information Form (see Appendix 1; see Figure 1 for an example) to describe your program’s characteristics. Consider the demographics your program currently serves, as well as future demographics you plan to serve if you foresee program growth.

Figure 1. Program Information Example

With your program information in mind, it is time to consider the various horse traits that will affect your selection. Each trait that we will discuss should be thoughtfully and realistically considered to determine the qualities that will best meet your clientele and program needs. It is important to remember that as you set the parameters for each trait, you will inevitably make assumptions as to how the trait will influence the horse’s behavior and capability. These assumptions, while necessary, don’t always hold true for all horses.

For example, you may set your age parameters for between eight and twelve years old because these horses are more likely to have appropriate physical capability and solid training. If you come across a seven-year-old that is sound and well-trained, you may adjust your age range and consider that younger horse. The key is to understand why you selected each trait, so that, in appropriate circumstances, you can adjust your search accordingly. Though it is important to note that there are certain traits you should not compromise on, such as soundness, behavior, and training.

We will next discuss the various traits that should be considered when selecting horses for your program.

Age

When determining the age range to search for, you should consider how age will impact the horse’s health, longevity, mental maturity, physical maturity, and life experiences. It is typically the low- and high-end ages that have drawbacks related to these factors, though age does not always equate to training and life experience. Many programs have a lower and upper age limit policy, often excluding young and old horses from consideration. During this discussion, we will assume that the horse has been trained and in work its whole life.

Young

A young horse (<6 years of age) is still developing mentally and physically. Some argue that mental maturity doesn’t occur until the age of six, yet many horses start their basic training the day they are born and are started under saddle as young as two years old[1]. Breed and temperament have a large effect on the horse’s propensity to pick up on training concepts. Some young horses will be energetic and reactive, while others are more docile and responsive.

Because the young horse is gaining experience and expanding its understanding of the human world, they may be inconsistent in their responses and behavior. A handler who is confident and experienced will be able to work with the horse through various training exercises and experiences, while an inexperienced handler may be unable to support the horse and progress them in their training. This is why middle-aged and older horses are often more suitable for beginners.

Equally as important as mental maturity is the physical development of the horse. Typically, much of a horse’s growth is completed by about two years of age, with full skeletal maturity being reached between the ages of four to six (i.e., closure of their growth plates)[2].

There are differing opinions regarding the optimal age for starting a horse under saddle and in hard work. The key to long-term success and health is to treat each horse as an individual. Their physical training should be completed in a progressive manner, consistent with their growth and capabilities. Working a horse too hard, too fast, regardless of its age, can lead to both short-term and long-term injuries. When looking at young horses, you should question how much stress has been placed on their still-developing joints. Consult with a trusted veterinarian to determine if this is a concern.

The upside of purchasing a young horse for your program is their potential longevity. They typically have healthier, sounder joints because they haven’t worked as hard and long as an older horse. You often know their history as they have had fewer owners in their short lifetime. The amount of training and effort you put into the young horse will pay dividends, as they will often work for your program for many years to come. Though it can be difficult to determine if a young horse will thrive in a lesson environment.

Middle-Aged

A middle-aged horse (7-12 years old) is the sweet spot in the age range. These horses typically have a variety of life experiences, which enable them to remain consistent in their training and behavior, without significant health issues arising from work or age, although some may require additional training. They often have plenty of life ahead of them, so that the time, training, and resources you put into them will pay off in the number of years they can successfully work in your program. The downside is that they will usually cost more than an older horse, but the anticipated longevity may be worth that price difference.

Older

An older horse (13-18 years old) is the been-there-done-that horse. They are usually predictable and well-versed in their job. This may be a suitable age range to search in, provided you conduct comprehensive health checks (which should realistically be completed for any horse of any age). They may require some form of physical maintenance as they age (e.g., daily medications, joint injections, consistent bodywork). You should balance their potential for longevity with their behavior and training. If taken care of well and blessed with good genetics, they can potentially work in your program for many years.

Old

An old horse (19 years or older) is a seasoned soul who typically has training to match their years. Old horses, if they have the right temperament and are serviceably sound, are frequently marketed as beginner or kid horses as they step out of hard work and into a slower-paced life. While some special horses may live for five to ten more years while continuing light work, most are reducing their workload and rapidly slowing down. Unfortunately, due to their age, their level of training doesn’t equate to their current physical ability as their joints degrade and health declines. It is challenging to predict how many years an old horse will be able to work comfortably in a lesson program, and therefore, the cost versus benefit can be difficult to weigh.

You may find that people are looking for homes for their retired horses and would like to donate them to your program. Be mindful when you consider these donation offers. A free horse can result in additional expenses, especially in veterinary care. As with any horse acquisition, but especially important for older horses, ensure you have a retirement plan in place.

Behavior & Training

The level of training a horse has, as well as their behavior on the ground and under saddle, are among the most important characteristics to consider when selecting a lesson horse. Programs should have specific expectations regarding a horse’s behavior and training. While you can certainly take an untrained horse or one with behavioral problems and retrain it, this process requires time, expertise, and patience. You should realistically consider what assets you have available to improve a horse’s behavior and training to know what kind of horse you can accept into your program.

To begin, look at your program information form. Based on the types of lessons you offer and the clientele you serve, how will a horse need to behave, and what skills will they need to perform to be successful and safe? During the assessment portion of this book, we will delve deeper into specific skills. For now, we will cover some basics related to unmounted, mounted, and other behaviors.

Unmounted Behaviors

A horse should be calm and attentive to their handler while on the ground. This begins from the moment a handler enters the horse’s living environment to catch them. Key behaviors to consider are catching and haltering, leading (including at the trot and through gates), standing tied, grooming, picking up feet, backing up, leading through obstacles, responses to activity and loud noises, and lunging.

Watch out for horses that exhibit dangerous behaviors, such as biting, kicking, rearing, bolting, barging, running into the handler, or pulling back while tied. These horses are not suitable for a lesson program.

Mounted Behaviors

A horse should be relaxed and responsive under saddle. No matter the discipline, horses should stand calmly for tacking, accept the bridle easily, and remain still while the rider mounts and dismounts. They should be responsive to up and down transitions through the walk, trot/jog, and canter/lope, while maintaining the tempo set by the rider.

Additionally, consider behaviors such as how the horse steers (whether using an indirect, direct, opening, or neck rein), their ability to collect, their frame, backup or rein back, pivot, turn on the forehand, turn on the haunches, lead changes, riding through obstacles, and responses to activity and loud noises. If your program includes lead line lessons, also consider how the horse responds to a horse leader and side walkers.

Again, steer clear of horses that exhibit dangerous behaviors, such as biting, kicking, rearing, bolting, bucking, and cinchy behavior while saddling. These horses are not suitable for a lesson program.

Other Behaviors

A horse’s behavior outside of the lesson environment is also key to their success in your program. Consider how the horse behaves with other horses, if they are used to living in a stall or turned out in a paddock, how they stand for the farrier, and how they are for veterinary work, including deworming and vaccines.

You need a horse that can settle into your barn routines and housing styles comfortably. For example, if your horses live together in a large herd, you should avoid horses that are highly combative with other horses, as they could injure themselves or others. Also, a horse that is difficult to trim or perform routine veterinary work on may be too much of a liability for your program.

Throughout all skills, you should consider how a horse behaves to various stimuli. Are they spooky? Do they get distracted? Do they stand calmly? Are they light and responsive to cues? A good horse will be responsive to the handler, but not overly sensitive. Because beginners are inconsistent and unclear in their cues at times, lesson horses should be able to handle a margin of error without growing anxious or reactive.

Remember, the behaviors and training that you expect will depend on your specific program. An adaptive horsemanship program that serves only walk/trot riders with physical disabilities may require a different type of horse than a program preparing youth to compete at their first horse show. What one trainer can retrain, another cannot. No matter how good a trainer you are, it takes time to train behaviors and skills solidly enough that a beginner can be successful with the horse. The less time you have, the more trained the horse should be before purchase. This will allow you to maintain their training without a major undertaking.

Of course, not all behaviors can be retrained sufficiently to be safe for a beginner or someone with a disability. If a horse demonstrates dangerous behaviors, regardless of its other qualities, steer clear. It is not worth compromising when it comes to the safety of your clients.

Breed

There are hundreds of different horse breeds and even more mixed breeds. A horse’s breed will give you some insight into their temperament and conformation. It may even be an indicator of the style of riding and training the horse has been exposed to.

That said, each horse is an individual, and you should see them as such. Even within a common breed such as the quarter horse, there is a wide range of temperament, sizes, and athletic abilities. A western pleasure-bred quarter horse is vastly different than a racing-bred quarter horse. While most horsemen have some degree of bias towards or against some breeds, keep an open mind in your searches and don’t immediately discount a horse just because they are or are not a certain breed.

Color

Horses come in a variety of colors, yet the coat color does not impact the horse’s ability to be a good lesson horse. An exception is the horse’s skin color. Horses with pink skin, such as cremellos, perlinos, or those with white face or leg markings, are prone to sunburn. They may need to wear a UV protective mask or sheet or be slathered with horse-safe sunscreen to prevent sunburns. Pink skin around the eyes is extra sensitive and can lead to future health issues such as cancer[3]. If you acquire a horse with pink skin, be prepared for the additional management steps that may be required.

Another health condition to be aware of is melanomas, which are often found in gray horses. Gray horses have a higher propensity for melanomas than other dark colored horses due to a genetic component. These typically grow under the tail head and around the genital areas, but can appear anywhere. While often benign, if malignant, they will cause serious problems by metastasizing to the lymph nodes or other organs[4]. While not necessarily a reason in and of itself to avoid gray horses, you should be mindful that you thoroughly examine the horse to ensure you catch any existing melanomas before purchasing, as this may influence your decision.

Conformation

Conformation is the way a horse is built and is key to the horse’s long-term soundness. When examining conformation, we want to consider the relationship between form and function. The way a horse is built, the straightness of their legs, and the length of their back all play key roles in how the horse will move and hold up over time. While some characteristics of good conformation apply to any horse, different disciplines will look for specific builds that make the horse more athletic and suitable for their job. When evaluating horses from a beginner lesson framework, we look for those that are foundationally correct in their build and movement, enabling them to support an unbalanced rider effectively.

When analyzing a horse’s conformation, the horse should stand square with its front and hind legs aligned. Then, look at the horse from the right and left side views, front view, and hind view. Each angle will reveal something different about the horse’s conformation. To start, we will discuss the overall balance.

Balance

A balanced horse will be able to support an unbalanced rider more effectively. To determine the horse’s balance, start by looking at them from the side. The horse should fit into a square as drawn from the withers to the ground and the point of shoulder to the point of buttock[5].

Next, divide the horse’s body into three parts: the shoulder, back, and hindquarters. If you draw a circle around each part, they should be roughly the same size. Deviations from this balance can result in various propensities. If a horse has a proportionally long back, it may be weak and less suited to carry a rider, while a short back can be hard to saddle fit. A shoulder that is too large may be difficult to turn. A small hindquarter can lead to underpowered movement.

Legs

When examining the horse’s legs, look at them from the side, front, and back views. Correctly built legs will be straight and aligned with the rest of the body, allowing them to move in a straight line. Deviations from the ideal will result in excess strain on the structures in the legs, including joints, tendons, and ligaments. You should also consider the hooves and examine the structure and angles. A well-built hoof and pastern will share an angle between 40 to 55 degrees[6].

Very few horses will have perfectly designed legs, but you should still be critical in your search. As you evaluate each leg, consider the type of stress the deviations will place on the horse. Search for horses with ideal, or close to ideal, leg conformation and avoid those with extreme deviations such as buck knees, calf knees, bowlegs, knock knees, bench knees, sickle hocks, post-legged, cow hocked, or bowed hocks, to name a few[7].

Barrel & Ribs

The width of the horse’s barrel greatly impacts the rider. Some horses have ribs that spring out, creating a larger surface area for riders to sit on[8]. A wide-barreled horse can be a good mount for a rider who has low tone and needs a wider base for balance. On the other hand, a more narrowly built horse is better suited for a rider who has high tone, a narrow build, or tight hips. It is important to have a variety of wide and narrow horses to suit your clients.

Health & Soundness

The health and soundness of the horse is the most important characteristic to consider when determining suitability for a lesson program. If a horse is unhealthy and unsound, they will not thrive in your program or be safe around your clients. It is also morally unfair to make a horse work while in pain.

As you look at horses to add to your herd, a comprehensive exam of the horse’s soundness and health will give you the information needed to determine if the horse has conditions that will need to be managed. The presence of a minor soundness issue may not exclude the horse from selection. Some horses, with proper care (e.g., joint injections, chiropractic care, massage therapy, medication) and a limited workload that suits their physical abilities, can thrive in a slow-paced lesson environment. Though the horse’s comfort and well-being must remain the priority.

Horses with known, unmanaged, or progressive soundness issues such as chronic lameness, degenerative joint conditions, and unresolved soft tissue injuries should be avoided. Additionally, horses with health issues such as a history of colic, severe dental disease, asthma, equine metabolic syndrome, pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction, and others should be carefully considered[9]. A trusted veterinarian should be consulted when considering acquiring a horse with known or suspected health issues. They can guide you in understanding the treatment process and risks associated with the horse’s condition.

While there is always a risk of injury, illness, or death, horses with known issues have a much higher risk. It is only a matter of time before the horse must be removed from your program, not only for their safety, but also for our ethical obligation to the horse. Because of this, you should not acquire a horse, even if it is a donation, that has significant unmanaged health problems. As a program, you must decide if you can manage a horse with some maintenance or if you need to continue your search for a healthier candidate.

Height

The height of your clients will influence the height of horses you need. Children and short clients will usually find more success on shorter horses because they can better wrap their legs around the barrel. For taller clients, taller horses with longer barrels will give them a better base of support.

In equine-assisted services lessons, such as adaptive riding or physical, occupational, or speech therapies incorporating horses, many riders require support from side walkers. Side walkers are individuals who walk alongside the horse and rider, providing various levels of physical support to the rider, including performing rider holds such as ankle and thigh holds. Horses must be of reasonable height to allow for the side walkers to perform their job.

Additionally, some therapists will manipulate the rider’s position while on horseback to meet their therapy goals. A horse too short or too tall will impede the side walker and therapist’s jobs. Typically, horses between 12.2-15.2 hands high will be ideal for EAS lessons that require additional personnel.

Muscling

Horses that are well-built with developed muscle across their topline, shoulders, and hindquarters will have the strength to carry a variety of riders and perform various athletic roles. Most importantly, for ridden horses, the topline should be well developed and strong. The topline includes the horse’s neck, back, loin, and croup[10].

Because the rider sits on the horse’s back, the horse must have a strong enough topline to support the rider’s weight. While muscle can be developed, it takes time and consistent quality work. When examining a prospective horse’s topline development, consider if they already have a strong back or if it will need to be improved upon. Some horses are genetically prone to carry more muscle, while others are lean.

The horse’s topline can also be an indicator of their current work routine and nutrition. If a horse is ridden in a hollow, disengaged frame or is missing proper nutrients, their topline will reflect this through a lack of proper muscle development. For example, horses that brace through their neck or are ridden in a false frame develop uneven muscle tone through their neck, possibly leading to an inverted neck where the underside of the neck is overdeveloped and the top of the neck is underdeveloped.

Performance History

Every discipline, competition area, or leisure activity requires various mental and physical efforts from the horse. Each discipline has various conformation, behavior, and training stereotypes that will translate to the horse’s ability to perform as a lesson horse, some more easily than others. For example, a trail horse may not do well in an arena, and a horse that’s only been ridden in an arena won’t be the ideal candidate for a trail riding operation. A pleasure horse may fit into your beginner program well, while a racehorse would have too much go.

It’s hard to know exactly how the horse will behave in a lesson simply based on their performance history, but it gives you a solid starting point. You should ask questions to understand how the horse performed in a specific activity and the experiences they had, including traveling to shows and other locations. Knowing how a horse performs in a stressful show environment and a chaotic warm-up pen will give valuable insight into the horse’s behavior. The more experiences the horse has had, the more well-rounded they will be.

Additionally, each discipline stresses the horse’s body in different ways. Horses that have a lot of miles on them from competing may develop arthritis sooner than a horse in the comparably light work of a recreational setting. You should be mindful of what the horse has done so that you can look deeper into the health of the horse’s joints and body.

Quality of Gait

The quality of a horse’s gait is greatly influenced by conformation and breed, though training can also play a role. The way a horse moves will significantly impact a rider’s success. It is easier for a rider to learn how to follow a horse’s movement in the walk, trot/jog, canter/lope when the horse has a smooth, even gait. Horses with choppy, short strides will naturally be bouncier, making it harder for the rider to follow the motion of the horse and increasing the concussion on the horse’s back.

As a horse moves, its back, shoulders, and hips oscillate, impacting the rider’s seat and movement. There are three directions of movement: forward and back, left and right (lateral), and rotational (which is when your hips move in a circular motion). Each horse will have a predominant movement pattern in each gait, which will influence how the rider absorbs and is impacted by the horse’s movement.

The way the horse impacts the rider is of special interest to therapists who incorporate the horse’s movement into their treatment plans. Different types of movement will lead to different outcomes for their patients. A rider focused on moving their hips in the same motion as walking will do well on a horse with a lot of rotational movement. Front-to-back movement will translate into the core and back stabilizing muscles, increasing their effort. Left and right movement will impact the rider’s core and side muscles. Programs that rely on the horse’s movement as a treatment strategy will want to have a diverse set of movement patterns.

Also, some riders who are sensory seeking will prefer horses with choppier, bouncier gaits. Riders who are overwhelmed with too much sensory input will do better with smoother-moving horses.

If your lesson program is focused on a specific discipline, such as western pleasure or dressage, the horse’s quality of gaits will influence your rider’s success. Western pleasure horses are known for smooth, slow gaits, while dressage typically seeks horses with bigger, flashier gaits. For your clients to be successful, it is essential to consider a horse that can move in the way required for the discipline, while also being manageable for a beginner.

The horse’s speed or tempo must also be considered when looking at the quality of their gaits. Ideally, a horse will have the ability to increase and decrease their tempo within a gait and perform smooth gait transitions. This will lead to more accurate, pleasurable rides. For example, when a rider first learns to trot, the horse should move slowly and smoothly. As a rider becomes stronger and develops their balance, a horse that can move into a bigger trot will allow the rider to practice intra-gait transitions, such as going from a trot to an extended trot.

A horse’s speed also affects riders who use side walkers and horse leaders to support them during lessons. A horse with a fast walk and trot can outpace the personnel, making it difficult to stay in proper, safe support positions. Thus, a slower horse would be more ideal for lead line lessons.

Finally, let’s discuss gaited horses. A gaited horse has a fifth gait (in addition to the walk, trot, canter, and gallop). Some gaited horses are not trained to trot and canter and can only perform their extra gait when asked to increase speed. The smoothness that gaited horses bring can help riders who are weak and struggle with following a horse’s movement and engaging their core. They can be phenomenal trail riding horses as they are smooth, comfortable, and can cover ground quickly. The downside of gaited horses is that they may not have defined trot and canter gaits, which may be needed for some lesson programs.

Temperament

A quality temperament, or a pleasant personality, is almost as important as health and soundness. Not every horse is suited for the mental and physical strain of lesson work. Horses with a pleasant temperament who are calm, unfazed by changes, consistent, curious, and enjoy engaging with people are more suited to the lesson environment than horses that are anxious, sensitive, and reactive.

Lesson horses deal with many different handlers and riders throughout not only their life, but on a day-to-day basis. Some horses react poorly to this inconsistency, resulting in behavioral problems, reactivity, and burnout.

Be aware that some horses are “one-person” horses, meaning they thrive with a small handful of individuals and thus do not do well in a lesson environment. Sometimes these horses start this way, and sometimes they develop this quality as they age and become burnt out through lessons. A one-person horse, or a horse just not suited for lesson work, will show stress signs as the number of people in their orbit increases. This may be seen as physical breakdowns such as sore backs, ribs, and unsoundness. Alternatively, it may be seen as a behavioral breakdown, where the horse loses its skills and becomes inconsistent in its responses, even exhibiting conflict behaviors such as biting, kicking out, bucking, or rearing. These behaviors often begin as small signs, such as not standing still, before escalating into more serious behaviors.

This makes it highly valuable to get a feel for a horse’s temperament to determine if they are likely to succeed in your lesson program. Every horse has a base temperament or personality that, despite training, won’t ever fully change. It is difficult to overcome a horse’s natural tendencies, so you should pay attention to what those tendencies are.

You can get a glimpse of a horse’s natural temperament by gathering information on how they handle multiple riders, different environments, and unexpected objects in their space. How does the horse react when they are unsure? Most horses will consistently react by fleeing or freezing. If a horse’s tendency is woah rather than go, this is a positive sign for their success as a lesson horse. More sensitive horses tend to be reactive and feed off the rider’s energy, resulting in a horse less suited for beginner lessons.

Additional traits to consider include if the horse is curious or fearful, engaged or stoic, tense or relaxed, docile or sensitive, bold or timid, dominant or submissive, affectionate or independent, social or aloof, inquisitive or wary, and expressive or reserved.

Sex

There are three sex options to consider when purchasing horses: stallion, gelding, and mare.

Stallions

Intact males are not recommended for adaptive lesson programs or beginner lesson programs due to their propensity to behave unpredictably around mares. While some stallions are well-behaved and adequately trained, there is an increased level of risk due to the stallion’s stud-ish tendencies. Care must be taken if stallions and mares are housed on the same property to ensure comingling does not occur.

Geldings

Castrated males are often level-headed, consistent horses due to the lack of the hormonal surges from testosterone. Some people are biased towards geldings because they exhibit more consistent day-to-day behavior, without the hormonal cycle swings seen in mares. Many geldings and mares get along well enough and can be housed in the same paddock, though this is not always the case. Some geldings will bond with a mare and become protective, disrupting herd dynamics. Geldings may even mount mares in season. It is essential to consider the geldings’ and mares’ herd behavior when housing them together.

Mares

Intact females can get a bad rap due to their fluctuation of hormones throughout the estrous cycle. Some people describe them as “moody,” “mare-ish,” and “fussy.” While their moods might change during stages of their cycle or in the spring when their cycle is starting again after the break of winter, mares can be wonderful lesson horses and should certainly not be discounted. If you do have a mare that has drastic mood swings or becomes sore, especially in the back and loin area at different times of their cycle, consult your veterinarian. Some supplements and medications can be used to reduce symptoms and control the estrous cycle. As with the geldings, it is important to consider the mares’ herd behavior when housing them with others.

Weight

The terms “easy” and “hard” keepers are sometimes used to reference the horse’s ability to gain and maintain weight. An easy keeper is a horse that maintains or gains weight with ease. They can thrive on an all-forage diet and don’t require special supplements to maintain a healthy weight. However, there are some horses, often ponies or heavier breeds, that are prone to gaining weight too easily, exceeding a healthy threshold. It is essential to have management strategies in place to prevent unhealthy weight gain.

On the other hand, a hard keeper is a horse that is difficult to maintain at a healthy weight. These horses are often underweight on an all-forage diet and require additional nutrition, such as concentrates or supplements, to maintain a healthy weight range.

Horses should be assessed on the body condition scale to determine if they are at a healthy weight. The ideal weight of a lesson horse is a horse that is between a four and a five on the body condition scale[11]. Underweight horses will lack muscle and energy. Overweight horses can become out of shape and develop secondary health issues due to their excess weight and the stress it places on their joints and body in general. Ideally, a veterinarian should be consulted to ensure each horse has everything needed to maintain a healthy weight while also ensuring proper nutrients are included in their diet.

A word of caution, when perusing the horse market, keep in mind that if a horse is severely underweight, as they gain weight and muscle, there may be personality changes. What was once a calm, low-energy horse may explode with energy as they gain the nutrients needed to sustain their body. This is a risk you must be willing to take if you choose to purchase a horse that needs some weight rehabilitation.

In addition to management considerations, weight will play a crucial role in the types of clients you can serve. A generally accepted standard is that horses can carry 20% of their ideal body weight in rider and equipment[12]. If you serve many large adults, you need to be thoughtful about the horse’s weight-carrying capacities. Additionally, horses that are unfit, under- or over-weight, or have injuries and other health issues, will not be able to carry as much weight. They may be able to only carry 15% or less of their body weight sustainably. As a program, you should have a client weight limit and ensure that you have enough horses to serve your clients.

Putting it All Together

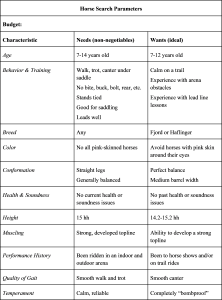

Now, based on your program needs, which you can see by referencing your Program Information form (see Appendix 1), describe a horse that will meet your program goals using the Horse Search Parameters form (see Appendix 2; see Figure 2 for an example). Describe each characteristic and place it into the need or want category. Needs are characteristics that are non-negotiable, while there is some flexibility regarding wants. For now, leave the budget and donation/lease/purchase section blank.

The completed form should be referenced when searching for new horses. It will assist you in making objective decisions when purchasing, leasing, or accepting a donation of a horse. Having a horse in your program that does not meet your needs will drain resources, so any horse you accept should have a designated role in your program.

Figure 2. Horse Search Parameters Example

Finally, armed with a clear goal, you are now ready to proceed to Step 2.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Understanding the stages of mental maturity in horses: When and why it matters. (n.d.). Back the Right Horse. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://backtherighthorse.com/understanding-the-stages-of-mental-maturity-in-horses-when-and-why-it-matters/#google_vignette ↵

- Dittmer, K. E., Gee, E. K., & Rogers, C. W. (2021). Growth and bone development in the horse: When is a horse skeletally mature? Animals, 11(12), 3402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11123402; Horses Inside Out. (2023, July 10). Skeletal maturity in horses: Growth plate ossification and age considerations. Horses Inside Out. Updated June 5, 2024. https://www.horsesinsideout.com/post/skeletal-maturity-in-horses-growth-plate-ossification-and-age-considerations ↵

- Kuhlwein, D. (2025, June 16). Sun damage in horses. Equine Chronicle. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://www.equinechronicle.com/sun-damage-in-horses/ ↵

- Young, A. (2024, December 18). Melanoma in horses. Center for Equine Health, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://ceh.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/health-topics/melanoma-horses ↵

- Melbye, D. (2024). Conformation of the horse. University of Minnesota Extension. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://extension.umn.edu/horse-care-and-management/conformation-horse ↵

- Melbye, D. (2024). Conformation of the horse. University of Minnesota Extension. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://extension.umn.edu/horse-care-and-management/conformation-horse ↵

- Melbye, D. (2024). Conformation of the horse. University of Minnesota Extension. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://extension.umn.edu/horse-care-and-management/conformation-horse ↵

- Melbye, D. (2024). Conformation of the horse. University of Minnesota Extension. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://extension.umn.edu/horse-care-and-management/conformation-horse ↵

- Ricard, M. (2024, July 18). Top 30 most common equine diseases: Guide to conditions affecting horse health. Mad Barn. Updated April 28, 2025. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://madbarn.com/common-equine-diseases/ ↵

- Lamprecht, E., Mueller, R., & Keegan, A. (n.d.). Identifying & evaluating your horse’s topline. Nutrena Feeds. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://nutrenaworld.com/identifying-evaluating-your-horses-topline/ ↵

- Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. (n.d.). The body condition score. Iowa State University. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://www.extension.iastate.edu/equine/body-condition-score ↵

- University of Minnesota Extension. (n.d.). Guidelines for weight-carrying capacity of horses. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://extension.umn.edu/horse-care-and-management/guidelines-weight-carrying-capacity-horses ↵