Assessing Community-Engaged Learning Impacts using Ripple Effects Mapping

Benjamin J. Muhlstein and Roslynn G.H. McCann, Ph.D.

Abstract

Communicating Sustainability, an upper-level undergraduate service-learning live broadcast course, was created at Utah State University to help students gain critical skills in communicating and participating in local sustainability efforts. Community-engaged learning was a key component applied in gaining and using these skills. This study sought to capture the impacts of this course on both its students and the community partners who worked with those students using Ripple Effects Mapping. Key findings include: powerful impacts on student learning, growth, and ability to engage in local movements, as well as clearly defined benefits for community partners. Included in this study are implications on how to apply Ripple Effects Mapping (REM) to measure impacts in other service-learning or project-based courses.

Introduction

World resource depletion has resulted in an increased conservation focus of many local, regional, and national movements. In 2017, for example, the United States (U.S.) received 18% of its power from renewable resources, an exponential growth from previous years (Morris, 2018). Up to 80 percent of the U.S. could be powered by renewable resources by 2050 (Mai, Sandor, Wiser, Schneider, 2012). Across the nation, hundreds of mayors are leading their cities towards positive actions against climate change (Climate Mayors, 2017). In the conservative state of Utah alone, three cities and one county have signed on to 100 percent renewable energy resolutions, and two cities have enacted plastic bag bans. Over 240 U.S. cities, counties and two states have enacted plastic bag bans, and Seattle has also banned single-use plastic cutlery and straws (Winslow, 2018). Organizations, institutions, and programs have emerged across the nation focusing on ‘regeneration,’ ‘sustainability,’ ‘permaculture’ and more, providing hopeful solutions to our current destructive and extractive lifestyles. How can higher education teach students sustainability in a way that prepares them to successfully act on and further these and other environmental efforts? And, is it possible to do so in a manner that also provides them with needed skills and knowledge for the future?

With these questions in mind, Communicating Sustainability, an upper-level undergraduate service-learning live broadcast course was created at Utah State University (USU). Key in the development of this course was the belief that students could learn critical skills in communicating and participating in sustainability efforts and could apply those skills during the course to effect change. To this end, service-learning became a key component and learning tool used in the class. Students overview fundamental concepts of sustainability, learn key marketing techniques effective in changing behavior, and either work individually if enrolled alone at a broadcast site, or are placed into small groups (two to four) in which they work with a community partner to enact environmental behavior change at the organizational level. Partners range from small non-profits to large, internationally reaching, for-profit corporations. Through this class, students should become more capable of carrying out the kind of change needed to create a more sustainable future.

The course has now been taught via live broadcast every spring since 2014. With six years of students and projects, it was time to find out what impacts the service-learning model was resulting in. To that end, we used Ripple Effects Mapping (REM) to measure the impacts of participating in this course/project on students and community partners. We held three sessions over the fall of 2018, all of them implementing the REM method described in more detail below. Two of the sessions involved students, one with past students (from 2014-2018) and one with students (then) currently taking the course (fall 2018). The final session included community partners (participation in one or more years between 2014 and 2018). The REM model applied to measure the impact of our course is the focus of this article, and should prove very helpful for others teaching service-learning courses and looking to evaluate the impact of this type of approach.

Communicating Sustainability

Communicating Sustainability is a certified community-engaged learning course through USU. The course goal is to “enact environmental behavior change through application of successful education and communication strategies,” and this goal is operationalized by six objectives:

- Identify definitions, common misconceptions, and key principles of sustainability.

- Think critically about sustainable living, including why people do and do not engage in sustainable behaviors.

- Explain models or theoretical frameworks that can be used for analyzing the questions: “Why do people act the way they do?” “What are the barriers to environmental behavior?” “How can we motivate people to act environmentally?”

- Use theoretical frameworks and marketing techniques to design comprehensive communication strategies to change behavior.

- Identify and apply effective facilitation, conflict management, messaging, and negotiation strategies.

- Consult with a community partner to develop and implement a comprehensive sustainability plan.

In lieu of exams and essays, student grades consist of in-class discussion and a weekly group meeting (10%), online discussions and timed reading check quizzes (20%), a class introduction presentation about the community partner they will work with (5%), at least three community partner meetings with notes and a reflection video submitted (15%), a first draft of a community-engaged learning report (15%), a newspaper article submission about what they are working on (5%), a final presentation to their community partner (15%), and a complete graphically appealing community-engaged learning report presented to the instructor and community partner (15%). Foundational to the class is a Community-Based Social Marketing framework, where students learn how to identify an issue, select a target behavior, conduct a barrier-benefit analysis, and then apply various marketing techniques including prompts, incentives, norms, convenience, commitment, and communication to enact environmental change at the organizational level. Most of the work occurs in small groups, with the exception of students enrolled alone at a broadcast site, or those wishing to work on their own project with instructor approval on a case-by-case basis. Final grades are based on their comprehension and application of the techniques with their partner, not in physical changes resulting from their work as these can often take longer than the course of one semester to be implemented (McKenzie-Mohr, 2011; Thomson & Brain, 2017). Aside from exceptions with instructor approval, the course instructor links groups with community partners. Partners over time have represented pet shelters, restaurants, ski resorts, grocery stores, schools, city officials, technology companies, on-campus programs and businesses, and more. Projects with these groups have focused on recycling, water conservation, anti-idling campaigns, plastic bag reduction, share the road campaigns, Earth day activities, among other sustainability topics.

Student Benefits of Service-Learning

Service-learning has existed in one form or another since the beginning of the twentieth century, but the pedagogy of this approach was popularized in the 1970s and early ’80s via cognitive psychologists (Morton, 1995; Kraft, 1996). The form of service-learning used in Communicating Sustainability is community-engaged learning. The National Commission on service-learning defines community-engaged learning as, “… a teaching and learning approach that integrates community service with academic study to enrich learning, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities” (NCSL, 2002, p. 3). With this definition in mind, community-engaged learning matched the model sought in Communicating Sustainability. Service-learning, properly implemented, is documented to have strong impacts on student academics, heightened civic engagement, higher multicultural awareness, development of career skills and more (Astin, Vogelgesang, Ikeda, & Yee, 2000; Schalge, Pajunen, & Brotherton, 2018; Warren, 2012). All of these skills are important for those seeking to play an active role in enacting positive environmental change.

Community Partner Experiences

Although evidence of the benefits to students in service-learning abound, the benefits to community partners vary in the literature, and frequently positive experiences occur alongside negative ones (Stoecker, Tryon, & Hilgendorf, 2009). As several authors have indicated, these results may often stem from a lax implementation of service-learning (Stoecker et al., 2009). Without a concise plan of what the service-learning should look like and a dedicated application of the approach, unintended consequences are likely. For this reason, the responsibility of creating student groups, choosing community partners, and outlining project expectations must be carefully planned by the instructor. As Eby (1998) discovered, “…if done poorly service-learning can teach inadequate conceptions of need and service, it can divert resources of service agencies and can do real harm in communities” (p. 8). As a result, however strong the impacts are with students, it is critical to ensure that community partners are also receiving beneficial impacts. With these imperatives in mind, we had three main goals in conducting our research:

- Discover what specific benefits or effects community partners were experiencing through Communicating Sustainability service-learning projects.

- Confirm that published benefits to students were achieved for this course.

- Determine any ripple effects stemming from class projects for both students and community partners and if these ripples conform with the stated goal and objectives of the course.

Ripple Effects Mapping

Ripple Effects Mapping uses a participatory process of Appreciative Inquiry (defined below) and collective mind mapping to discover, analyze and visually map program impacts (Emery, Higgins, Chazdon, & Hansen, 2015). This method for evaluating impacts has seen increasing use by Land-Grant University Extension programs based at the community-level. Some of the benefits of using this method include: it’s simple and relatively inexpensive to implement, it is capable of capturing both intended and unintended consequences, it produces a visual map which is helpful for reporting and it creates positive energy towards continued action (Kollock, Flage, Chazdon, Paine,& Higgins, 2012).

While variations of REM exist, all of them contain a few key features (Hansen, Higgins, & Sero, 2018). These include: Appreciative Inquiry, a participatory approach, and radiant thinking (mind mapping). After an introduction of facilitators and participants, every session of REM continues with Appreciative Inquiry, which fosters a positive way of thinking about the world (Hammond, 2013). The reasoning behind using this positive tone is explained well by Hansen and others (2018), “Appreciative Inquiry works because we know that people move in the direction of the stories they tell about themselves. You will make better progress by focusing on what is working well and then look for ways to apply those lessons to efforts that may be stalled or not having the impact you anticipated would occur” (p. 5).

After Appreciative Inquiry interviews in groups of two or three, the entire group moves into radiant thinking or mind mapping. There are several ways that REM variants achieve this, with some writing the mind map onto a large piece of butcher paper or board, others projecting mind mapping software, and others applying both methods at once (Emery et al., 2015). All of the methods require that participants drive the discussion. A moderator will guide the conversation, but only to keep participants on topic, ask for clarification, and offer probing questions to flesh out details. The moderator may also mind-map the discussion in real-time, though many use another person or two to do that job. As participants engage and reflect on their experiences, they quite often feel more connected to the topic and ready to further collaborative discussion (Vitcenda, 2014). Finally, as participants reflect over the mind map that their discussion created, additional stories or details may emerge. Participants leave this process energized towards further action, and REM coordinators leave with a wealth of stories and impacts, which then can be coded for further analysis and reported to stakeholders. The analysis process for Ripple Effects Mapping is flexible depending on researcher needs. Some projects have included a qualitative data coding process to identify emergent themes, others identify emerging themes and compare to existing frameworks, while others simply enter the created mind maps into a mapping software and then display them in a way to best emphasize their success (Emery et al., 2015). We used qualitative data analysis methods (inductive analysis) to identify themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and then cross-compared the themes with Community Capitals Framework (CCF). Community Capitals Framework was developed as a tool for community planning, measurement, and development. It has become one of the primary research approaches in community analysis and is often used in connection with REM (Emery & Flora, 2006).

The REM framework seemed well suited to our service-learning impact measurement goals. While REM has been used for a myriad of program evaluations, many of them focused on community Extension programs (Olfert et al., 2018). To our knowledge, our efforts represent the first implementation of REM to evaluate impacts from a community-engaged learning course. As an additional goal of this project, we sought to verify REM as a viable method of impact assessment for community-engaged learning.

Study Design

The design for this study included: outlining the questions, goals, and structure of the REM sessions through suggestions in the Advanced facilitator guide for in-depth ripple effects mapping by Hansen, Sero, and Higgins (2018), obtaining approval from USU’s Internal Review Board, organizing and contacting potential attendees, preparing and running REM sessions, and analyzing the resulting recordings and mind maps using inductive analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Our questions were influenced by typical REM procedure, beginning with Appreciative Inquiry (Hansen et al., 2018). As such, questions were generally positively worded and aimed at reflection. Our questions and methods were reviewed and approved by Utah State University’s Internal Review Board before the REM sessions were held, and examples of these questions can be seen below.

- What was your most satisfying moment working on the project?

- How has your work in Communicating Sustainability changed the way you think or do things?

- What was something unexpected that occurred from participating in this/these project(s)?

- What impact do you feel this project has had on the community? (Utah State University campus, the broader community, or both)

To determine who would attend the REM sessions, we first created a database of previously completed projects in Communicating Sustainability. The database contained basic information about students, their community partners, and projects from spring 2014 through spring 2018. This presented us with 45 different projects, 37 unique community partners, and 108 students. After completing the database, we systematically selected students and partners to contact. If current contact information for community partners was unavailable, or if the primary partner no longer worked with the company, they were excluded from the study. This process led to a total of 23 potential community partners. Many were located in Logan, where USU’s main campus is situated and most students attend the class, but a handful were from regional sites around the state. We attempted a variety of methods to contact these including personal contact, calling and email. Of those contacted, three more indicated or were found to no longer work in the same position, or contact information was incorrect. Initially, we had ten respond to a doodle poll confirming their possible attendance. Of these, six made it to the actual REM session. Many of these partners had worked with several different groups, representing ten projects between them. The community partners attending represented both on-campus businesses and off-campus organizations located in or near Logan, Utah. Students participating in the session were also selected through a similar process. After eliminating those that no longer lived within an hour’s drive of USU’s Logan campus, where the sessions would be held, and those that we lacked contact information for, we reached out to a total of 22 potential previous students. Several did not respond to contact attempts and several more indicated they would not be able to make the dates selected. Nine students attended that REM session. Students from this group worked with on-campus businesses and organizations as well as off-campus for-profit businesses. We also held an abbreviated REM session for current students during one of their final classes of the semester, with 17 of 19 students enrolled attending. All sessions followed the Ripple Effects Mapping process that has already been described, with a main facilitator, an assistant mapping ideas on a large whiteboard, and another assistant documenting key quotes stated in the audio-recorded session.

Analysis

Our analysis involved transcription, coding, and comparison with the Community Capitals Framework. All three mind maps were entered into Xmind mapping software (Xmind 8, 2017), organized for clarity, and had key quotes added. Transcriptions were manually typed verbatim, and names were changed to protect identity as was required by the IRB protocol. Transcriptions were checked by two researchers on the project for precision. Following entering and editing the maps in Xmind and transcribing the sessions verbatim, we coded the transcriptions using inductive analysis and then grouped major themes and corresponding quotes into capitals from CCF (See Table 1 for the Seven CCF capitals). From these groups, with comparison to our session mind maps, we narrowed the major themes that guided our results.

| The Seven Community Capitals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Cultural | Human | Social | Political | Financial | Built |

| Includes a community’s environment, rivers, lakes, forests, wildlife, soil, weather, and natural beauty. | This includes the diversity, traditions, and beliefs of the community. | This includes the skills and abilities of the residents as well as their ability to work in community projects. | This reflects the connections among people and organizations or the social glue that makes things happen. | This is the ability to influence standards, rules, regulations, and enforcement. | This includes the financial resources available to invest in community capacity building. | This is the infrastructure that supports the community. Built capital is often a focus of community development efforts. |

Results

Student Results

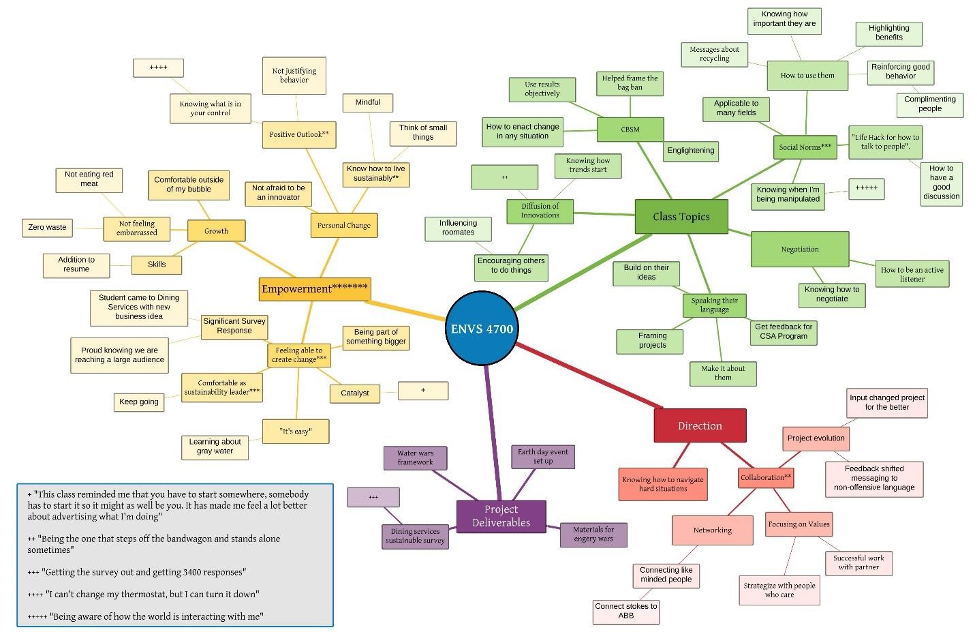

Given the many benefits students have been found to experience with community-engaged learning courses – from increased multicultural awareness to better grades (Novak, Markey, & Allen 2007) – we expected to find students in Communicating Sustainability having experienced some of these. In particular, our study was looking for benefits that would increase student ability to enact community sustainability, as well as providing them with “real world” experiences (Warren, 2012). In viewing the student mind maps (Figures 1 and 2) we can immediately see these, and many more benefits are being achieved. Analysis of the student mind maps and session transcriptions led to two main themes, which we will discuss below. These themes were selected from the Community Capitals Framework by analyzing topics discussed in each session and then categorizing them under one of the seven Community Capitals of natural, cultural, human, social, political, financial, and built (see Table 1). From this process, human and social capitals emerged as primary themes.

Growth of Human Capital

The theme that was most prominent in the student REM sessions was the development of human capital. This capital describes the skills, abilities, knowledge, and other capabilities a person may have (Emery & Flora, 2006). Early on during each session, students described how much they had grown from the course. Cynthia, a participant in our previous student session, summarized her feelings this way, “So [the course] not only [helped us in] gaining new skills but really developing and finding skills within yourself that you already had.”

Many of the skills and knowledge learned had an immediate use within the projects students were carrying out. As Mary explained, “[What we were taught applied to class] …and not in a preachy way ‘this will be useful one day.’ It was, ‘This will be useful and go and do it right now.’” Another student, Charles, described how these skills were applicable outside of his education:

Another really helpful thing is that we had to write a lot of reports in that class and we had to make them visually appealing, not only for the class, but for the community partner as well. So right now, I work for a consulting company and I have to write reports for the customers each week. That is a huge part of it and I am really lucky having already developed [that skill] because my boss just sends me to do my job and I actually know how to write a report. Which, I knew esoterically before, but had never practiced it. So that was actually a really helpful skill.

Another key development related to human capital was confidence, both in their new abilities and applying these outside of class and in their communities. As Jane mentioned, “I feel like that is kind of what this class has instilled in me… that the worst thing that could happen is a person could say no. You just move forward from that…” Others also added their feelings about this, “The course was stressful…but then it went so well, and now I am way more involved with the community than I would have been otherwise because I know can manage in that time and balance that with school work. That was definitely empowering.” Another stated it this way, “[The class]…really has catapulted me to be much more involved in the community. Much more than I ever was or probably ever would have been. I feel … now I just feel like really involved and inspired to make changes and keep doing stuff… and that is directly as a result of the class, 100 percent.” Students grew more comfortable trying new skills, but also in applying them outside of their education. The ripples of these new skills and abilities is best seen from our previous student map (Figure 1). As seen in multiple areas of Figure 1, students applied course content towards resumes, jobs and other applications. Students claimed job advancements, new positions and help getting into graduate school among other benefits gained from the skills they learned in the course. All of which ripples into various other community capitals.

Development of Social Capital

The second main theme we found relates to social capital; while not necessarily a goal of the course, it was nevertheless a significant outcome for many students. Social capital refers to the connections that glue together a community (Emery & Flora, 2006). As Kim, a previous student found, “…so just all of those connections really run deep. It almost feels like we are family, so like we said earlier I am not afraid to approach [a past student of Communicating Sustainability] and say ‘Hey, do you want to help with this plastic bag ban?’ And so, it really feels like we are just this big family that can support each other with whatever, whether we have met each other or not.” Students found that the connections they made were often significant and that they presented them with more contacts and opportunities. Several previous students have found themselves working with each other on projects in the community and others have found contacts through their projects. Deanna found and received several opportunities through her connections in class. When she needed one of her projects reviewed she sent it to her previous community partner, “…he read through my report right away and gave a lot of really good feedback. Because of the relationship we have, I feel that he took it more seriously than if we didn’t know each other that well. This was helpful in developing the project for the city.” Connections are being made between many different groups, as will be further explored in the business results. Connections made through the class have led students to have better projects, feel more comfortable with the sustainable lifestyle they wanted and led them to seek additional causes they can support. Notably, some previous students are volunteering their time in working with current students to achieve project goals. This is beneficial both to community partners and students.

Additional Notable Impacts

One of the benefits of holding separate sessions for previous and current students was that it allowed a view of impacts that are more immediate versus those that tend to come with time. While the themes discussed above apply to both sessions, the stories of the change current students were experiencing were quite powerful. Thus, even in the short term, this course was providing impetus to change and grow. As John, a then current student told,

This class has helped me with impetus to change [be]cause I have had sustainability convictions that I’ve wanted to implement, but I’ve always felt embarrassed to do it. Like when [we were challenged] to give something up to do something sustainable I picked not to eat red meat. I’ve always wanted to stop eating red meat and that was the catalyst to so that I don’t eat red meat anymore… At my house my wife won’t cook red meat anymore, my wife and my kids will still eat red meat like at a restaurant and stuff. But… It’s kind of interesting to be willing to stand up. I was really nervous to tell my mom. We were at my mom’s house and it was later and we were getting ready to go and it was an hour drive home and she asked, “do you want some hot dogs”. I said, sure [my kid] is hungry. She [was] fixing some hot dogs and she asked me, “do you want one” and I [told her], I don’t eat beef anymore. She said, “you don’t?” (Laughing) I mentioned, ‘no, it’s just something that I wanted to do” and she was okay….

From the impacts on student human and social capitals, we saw further ripples into other capitals by past and current students, including financial, cultural, and natural capitals. To give a few examples: some students gained jobs and higher positions which affects their financial capital.

Kim, from our previous students’ session shared her experience,

I felt like I was underlooked, underappreciated, underutilized, underpaid you name it… In turn when I interviewed for this position as a trainer I had to create a presentation and then present it, which heads up, at that point, not even a big deal at all! I could do that in my sleep after compared to what I had just done. I got four dollars more an hour, and now I have an office and appreciation. Additionally, the money we generate through the recycling program is given back to the employees every year at Christmas.

This is a great example of how these ripples can spread away from the participants and into the community. Also, many of the students, current and past, have changed their habits to be more sustainable and have introduced this to others leading to changes in the cultural capital and natural capital of the area. While these longer-term ripples are easily found among past students, the beginnings of these ripples were captured in the current student session. One group sent out a survey about sustainable practices for USU Dining Services and received over 3,400 responses, from which Dining Services is implementing top desired changes. Others, as mentioned earlier, have begun to not only embark in more sustainable living practices but to share those practices with others. Many of these ripples were recorded in the Community Partner results below.

Community Partner Results

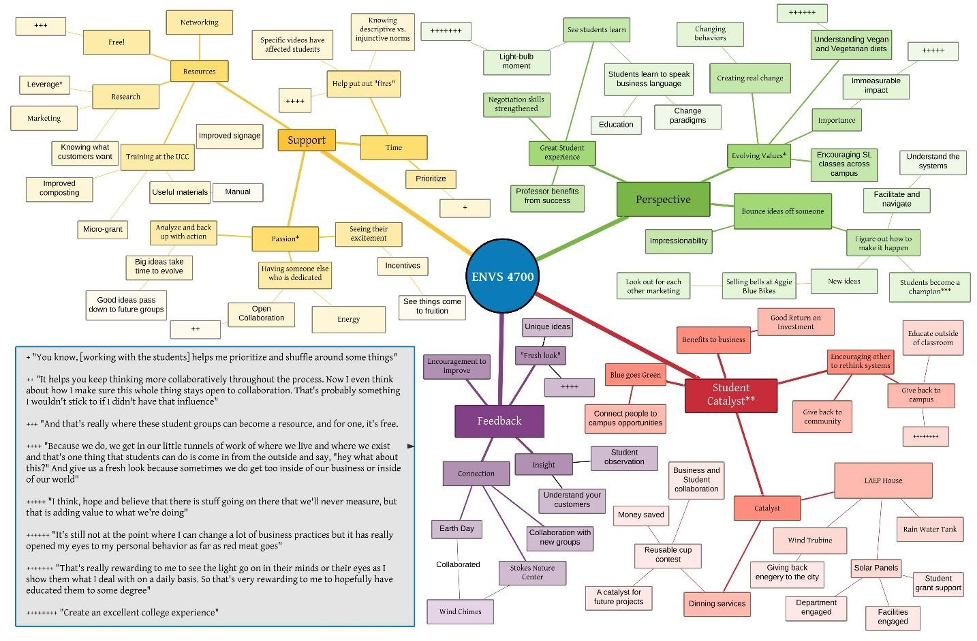

The session with our community partners was the most anticipated, due to the disputed nature of benefits for community partners engaged in service-learning projects in general. It was hoped the course would benefit not just the students, but also the community at large through the partners and respective businesses the students work with. The mind map of the community partner session is shown in Figure 3. While not every student project produced significant monetary results for a business, businesses are receiving benefits just by working with students. Our analysis led to two central themes being recognized, financial and cultural capitals.

Students Affecting Business Financial and Social Capital

Regarding financial capital, students are both providing resources and proving to be a resource for community partners. Provided resources came in many different forms. Discussed in the group were grants received, trainings for employees, market research, money saved, and more. Many of these provided financial capital for these businesses through either money saved or gained in a variety of methods. Often this financial capital is just one of the resources students bring. The resources come in other ways, revealed in our session, where students brought “ideas unrestrained.” This allowed for a reinvigoration for working on sustainability issues. “You get bogged down by the day to day survival mode,” reported one partner, “but then [the students] come in with all this energy and excitement, and that’s what I really love.” And another, “That sometimes breathes a breath of fresh air into the whole thing, and you kind of get reinvigorated by that. That’s one of the things that I think is so important…We take time to listen to them and find out what their cool ideas are.” In this fashion, a student’s passion is a type of resource to these partners. As one partner put it, “And that’s really where these student groups can become a resource, and for one, it’s free.” While not strictly monetary, students are helping businesses improve their financial capital.

An additional resource brought to businesses is the social connections related to these projects that build bridging links in the community. Collaboration frequently can make a project have much greater success. One such project revolved around upcycling unrecyclable bicycle parts to be wind chimes. At first, the community partner was unsure anyone would enjoy these new products. The students provided a connection to several other groups through which they found,

“…people loved those wind chimes! And we ran through them, and people couldn’t believe that we were giving it to them for free.” This type of success can be seen through collaboration, which is often facilitated by the students. In this example, the students partnered with a different nonprofit to make the wind chimes, strengthening a connection between two community organizations. As one other partner mentioned, “It helps you keep thinking more collaboratively throughout the process. Now, I even think about how I make sure this whole thing stays open to collaboration. That’s probably something I wouldn’t stick to if I didn’t have that influence.”

Cultural Capital and Long-term Impacts

The financial and social capital brought to the businesses through these projects were the shortest-term ripples that we identified. With the possible exception of the collaborations, most projects lasted for the duration of one semester, and that is not a long time to make lasting impacts. There have been a few exceptions where students have continued with the projects after the semester, but as one partner mentioned, “And then that really is the challenge, to [find] somebody that can give continuity to whatever [the project is].” This reality makes long term impacts from a project difficult to produce. The business owners in our session struggled to find someone to keep projects moving once students leave. Acknowledging this downfall of design, which can be addressed by assigning future student groups to continue or grow past projects while still being open to new partnerships, students are still leaving long term impacts on businesses, particularly in cultural capital.

Analyzing the mind map, we found that one of the major advantages working with students identified was a change in perspective. As one business partner put it, “I think from working with the student groups on the Share the Road and the Road Respect thing, it made me think more deeply about how I behave as a cyclist and setting a good example for other cyclists… I don’t think I would have ever come around to the bells if it wasn’t for the student groups.” In that case, not only were her personal habits affected, but she was able to change business tactics as well and start selling bike bells. Another, who works in the food industry, had a similar experience:

I’m a Utah boy born and bred, but it’s been very eye-opening and educational for me to meet with people about vegetarian and flexitarian diets. I never really understood the environmental impact of the meat industry. It’s still not at the point where I can change a lot of business practices, but it has really opened my eyes to my personal behavior as far as red meat goes. It’s amazing because you’d think that I’d know that, but when someone comes in, [it] brings that a little closer to home as opposed to something that people are doing in Princeton or UC Santa Barbara, it’s like another universe for us.

It’s Not All About the Business

Not every community-engaged project is going to experience high success as student motivations, and partner dynamics vary greatly. Regardless, our community partners showed that the intended results are not always the most important. As Sandy and Holland (2006) found, many community partners were more interested in the learning the students would receive during the project than the outcomes of the project itself. As one of their researched community partners put it, “We are co-educators. That is not our organization’s bottom line, but that’s what we do” (p. 34). Reminiscent of that sentiment, community partners in our study enjoyed working with the students, enjoyed the feedback, the flow of ideas and perspectives and even teaching students what it means to be in their profession. In discussing the role of students, one partner put it this way, “My piece represents outside the classroom. So, anything that I can do to support inside the classroom and educate outside the classroom are all big pieces…That’s really rewarding to me to see the light go on in their minds or their eyes as I show them what I deal with on a daily basis. So that’s very rewarding to hopefully have educated them to some degree.” Community partners are glad to be a part of the education students receive and have a desire to teach them.

Our partners primarily experienced financial, social, and cultural capital benefits, but the additional benefits as well outlined above. Though not principle themes, partners implemented physical features such as composters and water tanks through these projects. While the impacts of this study are not generalizable to other service-learning courses, the results did prove that our partnerships have been valuable in providing benefits to both students and community partners.

Discussion

One of the central goals of this project was to determine if students were receiving the benefits that are claimed for in service-learning literature. The results from the Ripple Effects Mapping sessions reaffirm the positive results of other studies conducted related to service-learning.

Students saw benefits to their learning, positive gains in employment, increased skill and abilities, better communication, connections, and networks. All of these are supported in the literature (Warren, 2012). We also saw an increase in social responsibility and activity. Additionally, students claimed to have taken more enjoyment out of this course than others, due in part to many of these benefits. These are the benefits that drive the popularity of service-learning and provide ample reason to continue its use.

While we had some inkling coming into this study what the results would be for the students, we had less of an idea where community partners would stand. What can be found in literature points to both positive and negative results, influenced largely by the type of relationship created through the projects (Morton, 1995; Sandy & Holland, 2006). What the REM session revealed was that semester-long projects produce select long-term results. That aside, we unexpectedly discovered that some projects are not ending at the end of a semester. As mentioned earlier, there are a few cases of students remaining and working with a project longer term, but increasingly more common are larger projects that are passed on for future students to continue. As one partner mentioned, “I think that the work you put in now is like you were saying, they’re baby steps, but it’s all on the way to bigger things as long as you keep working with students… Maybe they [the students] think it’s a failure, but it’s not. They’re just baby steps.” These continued projects, according to our participants, show potential for better, longer-lasting results and are a model the course instructor is furthering. Several of our partners have continued projects, which have benefitted from continued help from successive groups of students. In combination with the results found in the student sessions, we can see that while each project may only be a baby step for the community partner, students and partners alike are gaining from this process. Most importantly, with each step, there are additional unseen ripples expanding outward into the community.

Throughout this process, REM has proven itself to be useful in capturing impacts from student projects. In particular, capturing the stories and changes that have occurred in the personal lives of students and partners proved both useful and powerful. Through REM, we were able to confirm first-hand the power that Appreciative Inquiry has in propelling participants towards further action. Immediately following the past student session, those same participants started planning a clothing swap, which they saw as a solution to waste in student housing. We even heard from the current student session, which took place after the community partner session, regarding how their partner was further encouraged to work with them and had a few new ideas to try out. Although the results we have published are focused on the positives that we collected, we were also able to collect ideas on how the course could be further improved, which should help create larger impacts for those participating in the future. This includes suggestions by community partners of a one-page outline of the student projects and expectations for the partnership over the course of the semester, among others.

Conclusion

Our research sought to identify the benefits received by both students and community partners who have participated in Communicating Sustainability at USU through Ripple Effects Mapping. Largely, what we discovered matches current research into the benefits of service-learning. While

Ripple Effects Mapping did not uncover many hidden benefits of service-learning, it did prove very useful in measuring these impacts in a mind-mapping display with associated participant quotes. Through this process, we have discovered that Communicating Sustainability is indeed having the impacts desired. We were able to demonstrate to the University’s Center for Civic Engagement and Service-Learning, upper administration, and other educators that this course is making lasting and valuable impacts, for the students and for the community. Students are leaving this course better prepared to enact positive environmental change.

Also, while not reported here, we received feedback through the process to continue improving the course. This important fact should not be overlooked, as seen in the literature, service-learning mismanaged may not provide the benefits desired (Morton, 1995; Schalge et al., 2018). It should be our duty as educators to consistently monitor the impacts we have so as to better prepare those we teach. Due to small sample sizes, our results are not generalizable; rather, we encourage other programs to trial REM as an economical and effective method to ensure that their programs are also achieving their desired results. The following summarizes the REM model for measuring the impact of a service-learning class:

- Build a database of potential participants

- Design the session goal, objectives, and major guiding questions

- Submit for Institutional Review Board approval

- Contact participants with a request to attend and possible dates, stating clearly the intention, time commitment, and incentives (such as free dinner and beverages) to attending, and begin scheduling sessions

- Conduct sessions, record important quotes, have a facilitator map themes in real-time on a large display board, audio record the sessions

- Transcribe the sessions

- Enter/clean and organize mind map in software

- Analyze results through coding or other analysis

- Report your findings back to stakeholders and administrators.

References

Astin, A. W., Vogelgesang, L. J., Ikeda, E. K., & Yee, J. A. (2000). How service learning affects students. Higher Education, 144. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slcehighered/144

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Climate Mayors. (2017). Members. Retrieved from http://climatemayors.org/about/members/

Eby, J. (1998). Why service-learning is bad. Service Learning, General, Paper 27. http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slceslgen/27

Emery, M., Higgins, L., Chazdon, S., & Hansen, D. (2015). Using ripple effect mapping to evaluate program impact: Choosing or Combining the Methods That Work Best for You. Journal of Extension, 53(2), n2.

Emery, M. and C.B. Flora. 2006. Spiraling-up: Mapping community transformation with Community Capitals Framework. Community Development: Journal of the Community Development Society, 37: 19-35. Retrieved from http://www.ncrcrd.iastate.edu/pubs/flora/spiralingup.htm.

Hammond, S. A. (2013). The thin book of appreciative inquiry. Thin Book Publishing.

Hansen, D., Sero, R., & Higgins, L. (2018). Advanced facilitator guide for in-depth ripple effects mapping. Washington State University Extension. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2376/13110

Kollock, D. H., Flage, L., Chazdon, S., Paine, N., & Higgins, L. (2012). Ripple effect mapping:

A”radiant” way to capture program impacts. Journal of Extension, 50(5), 1-5.

Kraft, R. J. (1996). Service learning: An introduction to its theory, practice, and effects. Education and urban society, 28(2), 131-159.

Mai, T.; Sandor, D.; Wiser, R.; Schneider, T (2012). Renewable electricity futures study: Executive summary. NREL/TP-6A20-52409-ES. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Morris, D. (2018) Renewable energy surges to 18% of U.S. power mix. Fortune. Retrieved from http://fortune.com/2018/02/18/renewable–energy–us–power–mix/

McKenzie-Mohr, D. (2011). Fostering sustainable behavior: An introduction to community-based social marketing. New society publishers.

Morton, K. (1995). The irony of service: Charity, project and social change in service-learning.

Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 2(1), 19-32.

National Commission on Service-Learning. (2002) Learning in deed: The power of servicelearning for American schools [PDF file]. Retrieved from http://ed253jcu.pbworks.com/f/LearningDeedServiceLearning_American+Schools.PDF

Novak, J.M., Markey, V., & Allen, M. (2007). Evaluating cognitive outcomes of service-learning

in higher education: A meta-analysis. Communication Research Reports, 24(2), 149-157 Olfert, M., Hagedorn, R., White, J., Baker, B., Colby, S., Franzen-Castle, L., … & White, A.

(2018). An impact mapping method to generate robust qualitative evaluation of community-based research programs for youth and adults. Methods and Protocols, 1(3), 25.

Sandy, M., & Holland, B. A. (2006). Different worlds and common ground: Community partner perspectives on campus-community partnerships. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 13(1), 30-43.

Schalge, S., Pajunen, M., & Brotherton, J. (2018). “Service‐learning makes it real.” Assessing value and relevance in anthropology education. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 42(1), 6-18.

Stoecker, R., Tryon, E. A., & Hilgendorf, A. (Eds.). (2009). The unheard voices: Community organizations and service learning. Temple University Press.

Thomson, I. & Brain, R. (2017). A primer in Community-Based Social Marketing. Utah State University Extension. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2664&context=extension_cu rall

Vitcenda, M. (2014). Ripple Effects Mapping making waves in the world of evaluation.

University of Minnesota Extension. Retrieved from http://www.extension.umn.

edu/community/news/ripple-effect-mapping-making-waves-in-evaluation/

Warren, J. L. (2012). Does service-learning increase student learning?: A meta-analysis. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 18(2), 56-61.

Winslow, B. (2018) Moab bans single-use plastic bags. Retrieved from https://fox13now.com/2018/09/12/moab–bans–single–use–plastic–bags/

Xmind. (2017) Xmind 8 (version 3.7.2) [Software]. Available from https://www.xmind.net/xmind8–pro/