Enhanced Teaching Requirements: A Case Study of Instructional Growth on Student Academic Performance and Satisfaction in an Online Classroom

Mingzhen Bao, Ph.D.; Adam L. Selhorst, Ph.D.; Teresa Taylor Moore, Ph.D.; and Andrea Dilworth, Ph.D.

Abstract

Online and brick-and-mortar universities are continually looking for a model that maximizes the student experience with the goal of enhancing retention and graduation rates among all student populations. Online education with its asynchronous nature and adult student populations need to hold faculty accountable for student performance in the classroom. This case study examined the effect of enhanced faculty requirements developed for online teaching on student academic performance and satisfaction. The enhanced requirements focused on increased faculty communication, subject-matter expertise, discipline mentoring, immediate assistance, and relationship building. Researchers compared student performance and satisfaction in courses taught under regular requirements with those taught by the same instructor under enhanced requirements. Results indicated that the enhanced requirements increased student satisfaction and performance measured by the end-of-course survey and the course academic metrics (e.g., GPA, course completion rate, and pass rate).

Introduction

Online education (OE) began as a supplement to aid traditional classroom experiences. Today, with the advent of online degrees, OE is becoming the most sought after form of learning in adult student populations (Allen & Seaman, 2011, 2013; Gannon-Cook, 2010; Harasim, 2000; Mueller, Mandernach, & Sanderson, 2013; National Center for Education Statistics, 2016). Regardless of modality, faculty seem to be a key factor of student academic performance in higher education, and faculty expectations and delivery can vary greatly across instructors (Coppola, Hiltz, & Rotter, 2002; Umbach & Wawrzynski, 2005). The conveniences and flexibility of OE are evident, but due to the asynchronous nature of the student-faculty relationship, challenges are presented in online faculty expectation-setting (Kennedy, 2005; Liu, Bonk, Magjuka, Lee, & Su, 2013; Smith, 2009; Taylor-Massey, 2015; Trotter, 2008). As universities are continually looking for a model that maximizes the student experience with the goal of enhancing retention and graduation rates among all student populations, OE needs to hold faculty accountable for student performance in the classroom. This case study will examine the effect of enhanced faculty requirements developed for online teaching on student academic performance and satisfaction.

To address the challenges in faculty teaching expectations, the Quality Matters Higher Education Rubric that supports the continuous improvement of course design includes general instructor-related standards. The instructor’s self-introduction needs to be professional and available online, and the instructor’s plan for interacting with learners during the course needs to be clearly stated (Standards from the Quality Matters Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition). Hilke (2012) developed an online instructor skill set which described online instruction in the areas of content expertise, teaching strategies, social presence, and communications through writing, audio, and video. Similarly, Bailie (2014) stated that online instruction fell into three pillars: significant communication, presence, and timeliness. Universities formed committees consisting of professors, administrators, and policymakers to alter their faculty roles, including teaching expectations, to better serve students, programs, and institutions (Bell-Rose, 2016; Fogg, 2004). Shaw, Clowes, and Burrus (2017) compared faculty expectations from student and institutional perspectives and found that many of them were not aligned. Students appreciated faculty sharing expert knowledge and indicated that the institution should do more to promote a more standardized experience for students with all instructors held accountable to the same high standards. Students appreciated faculty accessibility and responsiveness. While institutions did state requirements for timeliness of responses from faculty to students, students indicated that because of the nature of online education, they wanted faculty to be available outside of the typical academic schedule. This was further supported by research from Bao, Selhorst, Moore, and Dilworth (2018) illustrating improved student achievement and satisfaction when instructors were contractually required to enhance their communications, engagement, and responsiveness.

It must be noted that institutions use various titles under which the responsibilities of online faculty are published. Universities such as Penn State World Campus, Purdue Online Learning, and Arizona State University offer instructor performance best practices and expectations that online faculty are encouraged to implement in the classroom. Washington State University’s Global Campus has produced a memorandum of understanding (WSU Global Campus Teaching Standards, 2018). Part of the document is specifically geared toward faculty interaction, stating that faculty should access the courses a minimum of three times per week and respond to student questions and concerns within 24 hours. As it relates to this study, the authors consider best practices and faculty expectations to be mostly interchangeable. While general information is provided, best practices encompass activities in which faculty are encouraged to engage. Oftentimes, best practices are subjective and loosely understood by faculty as recommendations in online courses. There is no specific set of rules such as time frame for responses to communications, number of responses to students, or how often faculty should be engaging with students in the course. On the other hand, faculty requirements are objectively stated and clearly defined with specific criteria that faculty must follow in their online teaching.

In this study, faculty teaching requirements will be examined, and requirement changes surrounding increased presence, communication, and feedback are expected to facilitate discipline mentoring, immediate assistance, and relationship building, which ultimately increase student academic performance and satisfaction in online courses. Examining teaching requirements in the context of three broad categories of presence, communication, and feedback helps conceptualize the requirement changes. Instructor presence is concerned with how visible instructors are to students in the course and their availability to students. Instructor communication encompasses contact with the students in the course. This can be one-to-one communication, one-to-many, and include tools such as emails, chats, and phone conversations. Instructor feedback focuses on the responses to students from instructors regarding their work in the course.

Instructor Presence

The social presence theory, posited by Short, Williams, and Christie (1976), discusses the salience with which people interact. The theory notes that the medium used as an impact on social presence may impact students utilizing OE (Schutt, Allen, & Laumakis, 2009). Baker (2010) used the social presence theory to investigate the impact of instructor immediacy and presence in online courses. He discovered that student learning cognition and motivation were impacted by instructor immediacy and presence in the online classroom. Similarly, Skramstad, Schlosser, and Orellana (2012) examined student perceptions of their instructors’ presence and timeliness in online communications. He found that, in online classrooms, positive student perceptions were illustrated in the majority of tests groups.

Furthermore, Ladyshewsky (2013) suggested that social presence in the online classroom had implications on student retention. He found that an increase in the instructor postings resulted in increased student course satisfaction. Lehman and Conceicao (2014) noted the importance of instructors to create presence, community, and trust in a course. While research illustrates the importance of instructor presence, many faculty are not trained on methods of enhancing presence in the online environment. Paquette (2016) found that when instructors were trained, they were better able to use social presence cues in the classroom. Additionally, this led to the enhanced use of social presence cues by the students in these courses.

Instructor Communication

Easton (2003) found the role of online instructors to be ambiguous and ill-defined. She posited that while communication skills of online instructors mirror those of traditional faculty, the expectations from students varied between the faculty populations. Instructor communication in OE traditionally takes place through interactions in discussion boards, announcements, written guidance, online lectures, emails, office hours, and asynchronous videos. In the online environment, these communication strategies are used not only to educate but also to build a more personalized relationship with each student.

Instructor outreach is a vital expectation for online faculty due to the asynchronous nature of course delivery. Whether through discussions, announcements, or more personalized emails, student-faculty interaction has a significant impact on student performance (Lundberg & Schreiner, 2004). Outreach serves not only to educate but also to identify students not engaged or those lacking understanding. Traditionally, students have been expected to initiate contact with instructors. However, due to the adult population of online students, proactive faculty may be able to foster stronger student relationships and create a level of comfort necessary for the online classroom.

Online office hours also provide a venue for student-faculty communication in OE. However, due to the various challenges associated with distance students, Rees (2016) claimed that traditional office hours did not seem effective. As most adult learners select OE for its flexibility, creating rigid office hours seems to impede that goal. Lowenthal, Snelson, and Dunlap (2017) suggested that the creation of live synchronous web meetings could create a viable alternative for students enrolled in asynchronous courses and enhance student performance in the classroom. Their study found that student participation increased from 10% to 50% in virtual office hours with flexible options over traditional methods.

Instructor-created audio and video messages are another way online instructors attempt to enhance the interpersonal element of communication. Ice, Curtis, Phillips, and Wells (2007) studied the effectiveness of audio feedback on the student learning experience. They found the use of audio communications coupled with written feedback was more appealing to students than text-based comments alone. Similarly, Aragon and Wickramasinghe (2016) found that instructor-made short videos focused on key concepts had a positive impact on student learning.

Instructor Feedback

In the online environment, providing substantive and useful feedback is vital to student growth and academic performance. It is more important to understand the nature of the student population in regard to instructor feedback. Huang, Ge, and Law (2017) categorized how students processed feedback. Some students were identified as self-motivated with a profound interest in the subject matter and sought a deeper understanding of course material. Others sought to meet minimal requirements for tasks. For many online adult learners, it would be helpful for instructors to tailor instructional feedback in a manner that motivated the students and pushed them for higher performance in the classroom.

Sadler (2010) posited that feedback provided a statement of performance through the assessment of student work as well as suggestions as to how a better response could have been prepared. Planar and Moya (2016) studied personalized and formative feedback in the online environment from the perspectives of the student, the instructor, and in consideration of the media by which the feedback was presented. They found that “feedback needs to constitute a dialogue between the person who facilitates it and the one who receives it. It must explicitly promote self-regulation and a proactive attitude on the part of the student towards it; at the same time, it needs to focus on the learning process and involve class colleagues” (p.198). In the online environment where students may be unable to discuss work with instructors synchronously, quality feedback becomes an especially important expectation for the faculty member.

The following case study examined teaching requirement changes surrounding presence, communication, and instructional feedback. It was hypothesized that if faculty requirements were enhanced, student academic performance and satisfaction in the online classroom would improve.

Methods

Course Model and Instructor Participant

Online undergraduate courses utilized for the study are worth three credits and are five weeks in length. Courses apply a standardized design, composed of weekly readings, discussion boards, assignments, and quizzes. Individualized instruction includes supplemental course content, interaction with students, and nature of feedback. An instructor in the Journalism and Mass Communication program participated in the study and incorporated enhanced teaching requirements to her courses between May and November 2017. Prior to this, she had been teaching the same courses for two years, applying regular requirements to the classroom.

Regular and Enhanced Teaching Requirements

Regular teaching requirements require instructors to post weekly guidance and announcements before the beginning of each week, answer student emails and questions within 48 hours, submit discussion grades within 72 hours after the end of each week, and provide assignment grades and feedback within six days after the submission due date.

Enhanced requirements focus on subject-matter expertise, discipline mentoring, immediate assistance, and student engagement. The instructor is required to apply the following to her classroom (see Table 1). Approaches to implement the enhanced requirements are to either replace or merge the regular requirements with the enhanced version.

| Instructor Presence |

|

|---|---|

| Instructor Communication |

|

| Instructor Feedback |

|

Training Provided to the Instructor

Before May 2017, enhanced teaching requirements were discussed twice among the instructor, her program chair, and college leadership. Virtual office hours were scheduled on three different weekdays and times to accommodate adult learners. Mentorship provided by the program chair included sharing with the instructor the overall goals of the program to create a more engaging space for students. The instructor received guidance on how to effectively include videos within the course and how to creatively share professional work with students to bridge the gap between classroom studies and a career in the field. After the enhanced courses were launched, the instructor continued to conduct weekly meetings with the chair to share classroom updates and reflect teaching behaviors and student learning experience. The chair also observed the enhanced courses regularly to ensure the alignment of teaching performance with enhanced requirements.

Operationalization of Student Performance and Satisfaction

Student academic performance was measured with average GPA, course completion, pass, and next-course progression rates. Pass rate describes the percentage of students who receive D- (60% of course grades) and above. Next-course progression rate lists the percentage of students continuing on to the next course. Student satisfaction was collected through the end-of-course survey.

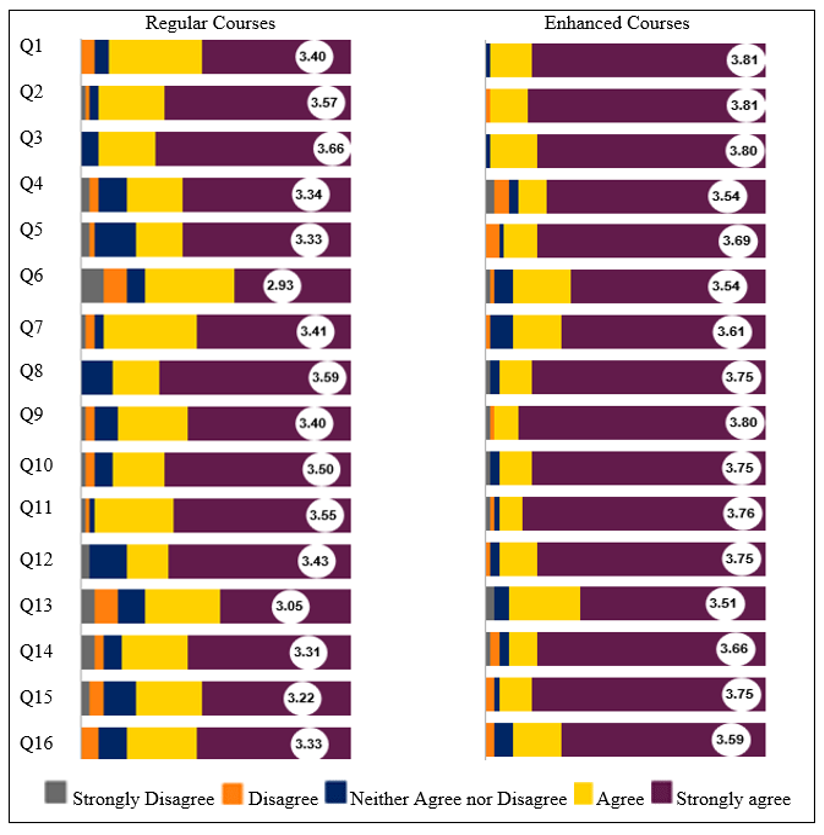

The end-of-course survey includes 16 questions. Questions 1, 5-6, 8-15 describe faculty’s instructional performance, Questions 2 and 7 focus on course content, and Questions 3-4, 16 assess overall learning experience (see Table 2). The enhanced faculty requirements are related to the survey questions under the instructional performance category in a way that faculty engagement may influence the overall perceived teaching quality. However, there is no one-to-one mapping between the enhanced requirements and the survey questions. Responses are measured on a five-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree gauging up to 4. The survey is available for students to complete during the last seven days of each course before final grades are released. Students receive emails indicating when the survey is available. The emails share the purpose of the survey, which is to help the University understand how well the course enables students to learn, and how the University can improve the way the course is presented in the future. Participation does not affect course grade, and the survey is conducted voluntarily.

| Instructional Performance | Q1 Clear instruction was given on how assignments would be graded. |

|---|---|

| Q5 I would recommend this instructor to another student. | |

| Q6 Instructions for completing assignments are clear. | |

| Q8 The instructor adds her/his perspective, such as knowledge and experience, to the course content. | |

| Q9 The instructor communicates and promotes high expectations. | |

| Q10 The instructor fosters critical thinking throughout the course. | |

| Q11 The instructor promotes active classroom participation of students. | |

| Q12 The instructor provides useful feedback for improving students’ quality of work. | |

| Q13 The instructor provides feedback in a timely manner. | |

| Q14 The instructor provides useful feedback for improving students’ quality of work. | |

| Q15 The instructor’s feedback aligns with her/his communicated expectations. | |

| Course Content | Q2 Course assignments require me to think critically. |

| Q7 The course content (assignments/readings/study materials) is engaging. | |

| Overall Learning Experience | Q3 Hard work is required to earn a good grade in this course. |

| Q14 I would recommend this course to another student. | |

| Q16 The quality of my educational experience has met my expectations. |

Results and Analyses

There were 48 courses taught by the instructor between 2015 and 2017. The enhanced requirements were used in 20 courses between May and November 2017. The regular version was used in 28 courses between January 2015 and April 2017, and 20 of them were randomly selected in the study. Thus, student performance and satisfaction data in 20 regular courses and 20 enhanced courses were analyzed using Repeated Measures in SPSS. In both instances, course content, size, and level were taken into consideration. The instructor taught all levels of major courses with a focus on JRN 201 and JRN 341 that consisted of 58.4% of her teaching load (28 out of 48 courses). Course enrollment was comparable between regular courses (mean = 6.21, sd = 3.10) and enhanced courses (mean = 6.95, sd = 2.82). Courses taught by other instructors between 2015 and 2017 were presented as a control group. No instructor in the control group resigned during the study period. Thus, they were all active and taught over time, though some might teach more sections than others. There were 41 courses taught by the instructors in the control group between May and November 2017. 216 courses were taught between January 2015 and April 2017, and 41 were randomly selected in the study.

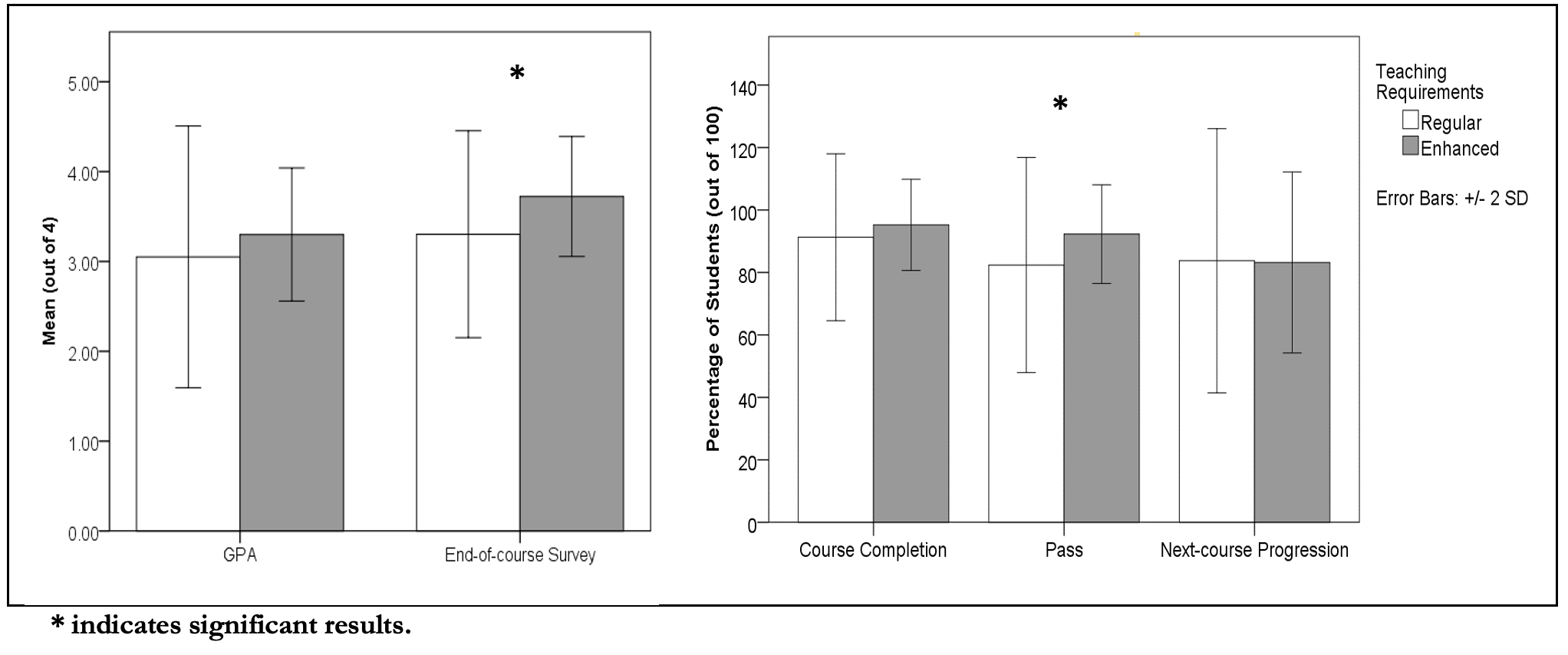

Improvement in courses taught under the enhanced requirements was noticed in average GPA, course completion rate, pass rate, and end-of-course survey score (Table 3, Figure1). Descriptively, average GPA and the end of course survey score were .25 points and .43 points higher for students taught under the enhanced requirements (out of 4 points, respectively). The course completion rate was up over 4%, and the pass rate was 8.4% higher in the enhanced courses. The next-course progression rate was down 0.5% in the enhanced courses. Statistically, improvement in the enhanced courses was significant in the pass rate (p = .02, ηp2 = .255) with a power of .677, and the end-of-course survey (p = .004, ηp2 = .363) with a power of .877. In the control group, student academic performance and satisfaction taught under regular requirements were not significantly changed over the time between 2015 and 2017 except that the next course progression rate was significantly lower between May and November 2017 than before (p = .028, ηp2 = .116) with a power of .607.

| Teaching Requirements | Case Study | Controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular (before) | Enhanced (after) | Regular (before) | After (after) | |

| Average GPA (out of 4) | 3.05 | 3.30 | 2.81 | 2.75 |

| Course Completion Rate (%) | 91.27 | 95.24 | 93.10 | 95.96 |

| Pass Rate (%) | 82.38 | 90.79 a | 84.00 | 86.37 |

| Next-course Progression Reat (%) | 83.76 | 83.20 | 85.65 | 78.22 a |

| End-of-course Survey Score (out of 4) | 3.30 | 3.73 b | 3.60 | 3.40 |

| a = p<.05, b = p<.01. | ||||

It was noted in the end-of-course survey results that student satisfaction with instructional performance was improved in the enhanced courses (Figure 2, Questions 1, 5-6, 8-15 in Table 2). It was also worthwhile to notice that students were more satisfied with course contents, assignments, study materials (Questions 2 and 7 in Table 2) and overall learning experience (Questions 3-4, 16 in Table 2) in the enhanced courses, which shed light on the impact of teaching behaviors on student engagement, use of course materials, and learning satisfaction. To further examine if student satisfaction in enhanced courses was aligned with the enhanced teaching requirements, some of the students’ verbal comments in the survey were quoted below (see Table 4). It was noted that students in the enhanced courses appreciated the instructor for the timely guidance, detailed feedback, subject-matter expertise, multimedia resources, and clear communications that she brought to the classroom. Consistently, they shared positive comments on the courses and overall learning experience in enhanced courses. Comparatively, fewer comments were received by instructors in the control group between May and November 2017. The authors noticed that positive comments from the control group on instruction and the courses were less targeted. Other comments in the control group identified opportunities for improvement in the areas of detailed feedback, clear instructions, and prompt email replies.

| Enhanced Courses | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Instructional Performance | I appreciate Dr. X’s positive and constructive feedback. | Y is a great instructor. I love taking any course he is teaching. |

| I know what her [Dr. X’s] expectations are, and she helps us along in any way possible | Thank you for everything. I highly recommend this course and especially Instructor Z to anyone interested in the field of Journalism. | |

| She reaches out more than other teachers. I look forward to the next class with her | The instructor fails to give good feedback on how the students can improve their work. | |

| My instructor was awesome and very informative and fair. | The instructor does not give clear instructions on assignments. | |

| Dr. X is one of the best instructors that I have experienced in my academic endeavors. She is fair, understanding, engaged, unbiased, inclusive, considerate, passionate, timely, and added to a human element to an online class. I cannot say how moved I am by her attention to each student and their needs, including one with hearing impairment for an assignment. Dr. X was awesome in explaining to us how to approach our task. I truly value this experience and wish her well! | There was a little issue of the instructor replying to us for the first part of the course through emails, but it got better as the class went on. | |

| Course and Overall Learning Experience | Love this class. | Great course. |

| I enjoyed this course, Great course and learned a lot. | I’m satisfied with this class. This instructor has made my experience as a student fantastic. | |

| This class was really fun and insightful. | ||

| This class was great, Dr. X. is the best. |

Discussion and Conclusions

Following the analysis of regular and enhanced teaching requirements, distinct differences were seen in student metrics. First, the pass rate for students taught under the enhanced requirements was significantly higher than the rate for students taught under regular requirements. With an 8.4% difference between students in groups of 40 total courses, this provides strong evidence that the enhanced requirements designed to improve faculty-student communication, faculty presence, and instructor feedback have a real-world impact on the student academic performance in the enhanced courses.

Student satisfaction, as measured by the end-of-course survey, also showed significant differences. Students under the enhanced requirements rated the course 0.43 points higher on a 4-point scale on the survey than students under regular requirements, significant at p<0.01. There was a small fear by researchers that the enhanced requirements might negatively alter the student satisfaction within the courses due to a perceived increase in course workload. Additionally, high functioning adult students often wish to be left alone to do work at their pace with little intervention. However, data illustrates a significant increase in satisfaction across all courses, quelling these fears.

In addition to the student pass rate and the end-of-course survey score, a trend for increased course completion and increased course GPA was also seen across groups. Significance was likely lowered by the small sample size in the study. However, we believe this data provides further evidence supporting the enhanced requirements. Course progression (students beginning their next course within two weeks of this course completion) was significantly decreased in the control group throughout May and November 2017. The decrease was not noticed in the enhanced courses. As the University utilized in the study offers 50 course starts per year, the flexibility of students’ schedules allows students to take two or more weeks off between courses. It does appear that enhanced teaching requirements do not lead to students progressing at a slower pace.

Researchers wondered if the instructor’s general teaching improvements over time might contribute to the student improvements in the case study. The results indicated that there was no significant student improvement in regular courses taught by instructors over time in the control group between 2015 and 2017. The instructor in the case study reflected that the training she received before the enhanced courses was less about learning new skills, and more about understanding the connections among heightened faculty engagement and consistently implementing the requirements across all her courses. She admitted that she acquired the skills of managing virtual office hours and video lectures before the case study, as the University provided professional development webinars to all instructors on a regular basis with topics to improve instruction. The key part was actively practicing the enhanced requirements both in and out of class and ensuring her teaching performance was aligned with the requirements, which was not a priority prior to the case study, nor for other instructors teaching regular courses.

Based on the data presented, the study appears to support the hypothesis that enhanced requirements increase student satisfaction and performance as measured by the survey and the pass rate. Administrators at asynchronous online universities with largely adult populations may see improved student satisfaction and academic performance in the classroom by adopting enhanced teaching requirements among faculty. However, the question remains as to time availability for faculty, consisting of adjunct instructors and full-time faculty with research and service commitments. Teaching roles, such as lecturers and faculty-of-practice instructors, might increase communication and thus increase student performance. Further research addressing this question may be needed.

Finally, the sample size in this case study consisted of one faculty member. While this does provide consistency across all sections of courses, it is not clear if similar results would arise in other cases. As such, further expansion of the enhanced requirements to additional faculty and disciplines could help to provide an answer to this question. Faculty communication, presence, and instructional feedback appear to have a significant impact on student academic performance and satisfaction in asynchronous online classrooms with adult students. While further investigation is needed to address the extent of these improvements, enhanced requirements provide promising results with higher course pass rates and student satisfaction for online universities.

References

Allen, I. E, & Seaman, J. (2011). Going the distance: Online education in the United States. The Online Learning Consortium. Retrieved from https://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/goingthedistance.pdf

Allen, I. E, & Seaman, J. (2013). Changing course: Ten years of tracking online education in the United States. The Online Learning Consortium. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED541571.pdf

Aragon, R. & Wickramasinghe, I. (2016). What has an impact on grades? Instructor-made videos, communication, and timing in an online statistics course. Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, 6(2), 84–95.

Bailie, J.L. (2014). Do instructional protocols placed on online faculty correlate with learner expectations? Journal of Instructional Pedagogies. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1060080.pdf

Baker, C. (2010). The impact of instructor immediacy and presence for online student affective learning, cognition, and motivation. The Journal of Educators Online, 7(1). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ904072.pdf

Bao, M., Selhorst, A., Moore, T., & Dilworth, A. (2018). An analysis of enhanced faculty engagement on student success and satisfaction in an online classroom. International Journal of Contemporary Education, 1(2), 25-32.

Bell-Rose, S. (2016). A path forward for faculty in higher education. Higher Education Today. Retrieved from https://www.higheredtoday.org/2016/12/19/path-forward-faculty-higher-education/

Coppola, N., Hiltz, S. R., & Rotter, N. G. (2002). Becoming a virtual professor: Pedagogical roles and asynchronous learning networks. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(4), 169–189.

Easton, S. (2003). Clarifying the instructor’s role in online distance learning. Communication Education, 52(2), 87–105.

Fogg, P. (2004). For these professors, “practice” makes perfect. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/For-These-Professors/31149

Gannon-Cook, R. (2010). What Motivates Faculty to Teach in Distance Education? Lanham, MD: University Press of America, Inc.

Harasim, L. (2000). Shift happens: Online education as a new paradigm in learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 3(1-2), 41-61.

Hilke, J. (2012). Competency standards for teaching online. Retrieved from https://courses.frederick.edu/CDL/InstructorCompetencies.pdf

Huang, K., Ge, X., & Law, V. (2017). Deep and surface processing of instructor’s feedback in an online course. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 20(4), 247–260.

Ice, P., Curtis, R., Phillips, P., & Wells, J. (2007). Using asynchronous audio feedback to enhance teaching presence and students’ sense of community. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(2). 3-25.

Kennedy, D. (2005). Standards for online teaching: lessons from the education, health and IT sectors. Nurse Education Today, 25(1), 23-30.

Ladyshewsky, R. K. (2013). Instructor presence in online courses and student satisfaction. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 7(1), Article 13.

Lehman, R. M., & Conceicao, S. C. O. (2014). Motivating and retaining online students. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Liu, X., Bonk, C.J., Magjuka, R.J., Lee, S., Su, B. (2005). Exploring four dimensions of online instructor roles: a program level case study. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(4). Retrieved from https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/sites/default/files/v9n4_liu_1.pdf

Lowenthal, P. R., Snelson, C., & Dunlap, J. C. (2017). Live synchronous web meetings in asynchronous online courses: Reconceptualizing virtual office hours. Online Learning, 21(4), 177-194.

Lundberg, C. A. & Schreiner, L. A. (2004). Quality and frequency of faculty-student interaction as predictors of learning: An analysis by student race/ethnicity. Journal of College Student Development 45(5), 549-565.

Mueller, B., Mandernach, B. J., & Sanderson, K. (2013). Adjunct versus full-time faculty: Comparison of student outcomes in the online classroom. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(3), 341-352.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2016). Digest of Education Statistics 2014. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016006.pdf

Paquette, P. (2016). Instructing the instructors: Training instructors to use social presence cues in online courses. Journal of Educators Online, 13(1), 80-108.

Planar, D., & Moya, S. (2016). The effectiveness of instructor personalized and formative feedback provided by instructor in an online setting: Some unresolved issues. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 14(3), 196–203.

Rees, J. (2016). Office Hours are Obsolete. Retrieved from https://chroniclevitae.com/news/534-office-hours-are-obsolete

Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: Developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 535–550.

Schutt, M., Allen, S., & Laumakis, M. (2009). The effects of instructor immediacy behaviors in online learning environments. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 10(2), 249–252.

Shaw, M.E., Clowes, M.C., & Burrus, S.W.M. (2017). A comparative typology of student and institutional expectations of online faculty. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. Retrieved from https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/summer202/shaw_clowes_burrus202.html

Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Skramstad, E., Schlosser, C., & Orellana, A. (2012). Teaching presence and communication timeliness in asynchronous online courses. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 13(3), 183-188.

Smith, R.D. (2009). Virtual voices: Online teachers’ perceptions of online teaching standards. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 17(4), 547-571.

Standards from the Quality Matters Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. Retrieved from https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Taylor-Massey, J. (2015) Redefining teaching: The five roles of the online instructor. Valued: Education + Your Life. Retrieved from http://blog.online.colostate.edu/blog/online-teaching/redefining-teaching-the-five-roles-of-the-online-instructor/

Trotter, A. (2008). Voluntary online-teaching standards come amid concerns over quality. Education Week, 27(26), 1-2.

Umbach, P.D. & Wawrzynski, M.R. (2005). Faculty do matter: The role of college faculty in student learning and engagement. Research in Higher Education, 46(2), 153–184.

WSU Global Campus Teaching Standards (2018). Academic Outreach and Innovation. Retrieved from https://li.wsu.edu/documents/2018/09/wsu-global-campus-teaching-standards.pdf/

Allen, I. E, & Seaman, J. (2011). Going the distance: Online education in the United States. The Online Learning Consortium. Retrieved from https://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/goingthedistance.pdf

Allen, I. E, & Seaman, J. (2013). Changing course: Ten years of tracking online education in the United States. The Online Learning Consortium. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED541571.pdf

Aragon, R. & Wickramasinghe, I. (2016). What has an impact on grades? Instructor-made videos, communication, and timing in an online statistics course. Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, 6(2), 84–95.

Bailie, J.L. (2014). Do instructional protocols placed on online faculty correlate with learner expectations? Journal of Instructional Pedagogies. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1060080.pdf

Baker, C. (2010). The impact of instructor immediacy and presence for online student affective learning, cognition, and motivation. The Journal of Educators Online, 7(1). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ904072.pdf

Bao, M., Selhorst, A., Moore, T., & Dilworth, A. (2018). An analysis of enhanced faculty engagement on student success and satisfaction in an online classroom. International Journal of Contemporary Education, 1(2), 25-32.

Bell-Rose, S. (2016). A path forward for faculty in higher education. Higher Education Today. Retrieved from https://www.higheredtoday.org/2016/12/19/path-forward-faculty-higher-education/

Coppola, N., Hiltz, S. R., & Rotter, N. G. (2002). Becoming a virtual professor: Pedagogical roles and asynchronous learning networks. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(4), 169–189.

Easton, S. (2003). Clarifying the instructor’s role in online distance learning. Communication Education, 52(2), 87–105.

Fogg, P. (2004). For these professors, “practice” makes perfect. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/For-These-Professors/31149

Gannon-Cook, R. (2010). What Motivates Faculty to Teach in Distance Education? Lanham, MD: University Press of America, Inc.

Harasim, L. (2000). Shift happens: Online education as a new paradigm in learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 3(1-2), 41-61.

Hilke, J. (2012). Competency standards for teaching online. Retrieved from https://courses.frederick.edu/CDL/InstructorCompetencies.pdf

Huang, K., Ge, X., & Law, V. (2017). Deep and surface processing of instructor’s feedback in an online course. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 20(4), 247–260.

Ice, P., Curtis, R., Phillips, P., & Wells, J. (2007). Using asynchronous audio feedback to enhance teaching presence and students’ sense of community. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(2). 3-25.

Kennedy, D. (2005). Standards for online teaching: lessons from the education, health and IT sectors. Nurse Education Today, 25(1), 23-30.

Ladyshewsky, R. K. (2013). Instructor presence in online courses and student satisfaction. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 7(1), Article 13.

Lehman, R. M., & Conceicao, S. C. O. (2014). Motivating and retaining online students. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Liu, X., Bonk, C.J., Magjuka, R.J., Lee, S., Su, B. (2005). Exploring four dimensions of online instructor roles: a program level case study. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(4). Retrieved from https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/sites/default/files/v9n4_liu_1.pdf

Lowenthal, P. R., Snelson, C., & Dunlap, J. C. (2017). Live synchronous web meetings in asynchronous online courses: Reconceptualizing virtual office hours. Online Learning, 21(4), 177-194.

Lundberg, C. A. & Schreiner, L. A. (2004). Quality and frequency of faculty-student interaction as predictors of learning: An analysis by student race/ethnicity. Journal of College Student Development 45(5), 549-565.

Mueller, B., Mandernach, B. J., & Sanderson, K. (2013). Adjunct versus full-time faculty: Comparison of student outcomes in the online classroom. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(3), 341-352.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2016). Digest of Education Statistics 2014. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016006.pdf

Paquette, P. (2016). Instructing the instructors: Training instructors to use social presence cues in online courses. Journal of Educators Online, 13(1), 80-108.

Planar, D., & Moya, S. (2016). The effectiveness of instructor personalized and formative feedback provided by instructor in an online setting: Some unresolved issues. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 14(3), 196–203.

Rees, J. (2016). Office Hours are Obsolete. Retrieved from https://chroniclevitae.com/news/534-office-hours-are-obsolete

Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: Developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 535–550.

Schutt, M., Allen, S., & Laumakis, M. (2009). The effects of instructor immediacy behaviors in online learning environments. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 10(2), 249–252.

Shaw, M.E., Clowes, M.C., & Burrus, S.W.M. (2017). A comparative typology of student and institutional expectations of online faculty. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. Retrieved from https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/summer202/shaw_clowes_burrus202.html

Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Skramstad, E., Schlosser, C., & Orellana, A. (2012). Teaching presence and communication timeliness in asynchronous online courses. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 13(3), 183-188.

Smith, R.D. (2009). Virtual voices: Online teachers’ perceptions of online teaching standards. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 17(4), 547-571.

Standards from the Quality Matters Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. Retrieved from https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Taylor-Massey, J. (2015) Redefining teaching: The five roles of the online instructor. Valued: Education + Your Life. Retrieved from http://blog.online.colostate.edu/blog/online-teaching/redefining-teaching-the-five-roles-of-the-online-instructor/

Trotter, A. (2008). Voluntary online-teaching standards come amid concerns over quality. Education Week, 27(26), 1-2.

Umbach, P.D. & Wawrzynski, M.R. (2005). Faculty do matter: The role of college faculty in student learning and engagement. Research in Higher Education, 46(2), 153–184.

WSU Global Campus Teaching Standards (2018). Academic Outreach and Innovation. Retrieved from https://li.wsu.edu/documents/2018/09/wsu-global-campus-teaching-standards.pdf/