Promoting Second Language Socialization Through Course Projects

Elena Shvidko, Ph.D.

Abstract

For many international students who are second language (L2) learners, successful integration in the new academic and socio-cultural environment is inseparable from their language socialization. Classroom teachers are well positioned to support students’ adaptation, and through course materials, projects, and activities they can encourage students’ successful socialization and promote their learning. Based on the principles of L2 socialization theory, this article describes how the projects of the course taught in the Intensive English Language Institute aimed at achieving two objectives: 1) foster students’ cross-cultural interaction and participation in various activities in- and outside the classroom, and 2) increase students’ opportunities to communicate in the target language, thus allowing them to develop more advanced linguistic forms.

Introduction

Studying in a foreign country offers a range of experiences that can enrich students’ academic, linguistic, and cultural lives. However, along with the benefits that international students obtain from pursuing their education abroad (e.g., Baker‐Smemoe, Dewey, Bown, & Martinsen, 2014; Lee, Therriault, & Linderholm, 2012; Milian, Birnbaum, Cardona, & Nicholson, 2015), they may also encounter a number of challenges, faced almost on a daily basis. These challenges may be particularly noticeable at the very beginning of their college experience. Indeed, the first few semesters can be intellectually and emotionally difficult to all students—both domestic and international (Shvidko, 2014). The latter, however, encounter additional hurdles related to language barriers, culture shock, and intercultural misunderstandings (Andrade, 2006; Hsieh, 2007; Poyrazli, Kavanaugh, Baker, & Al‐Timimi, 2004).

Having once been an international student myself, I experienced that studying at a foreign university can be absolutely overwhelming, at times even discouraging, and it certainly requires a great deal of patience, hard work, determination, and perseverance. Along with the learners’ own efforts, however, their adaptation to a new academic and social environment is impossible without support from others, including those at the university (Bista & Foster, 2016; Shapiro, Farrelly, & Tomaš, 2015). This is particularly true for instructors, as they are the ones who interact with students on a regular basis, and can establish a positive environment in their classes that will promote international students’ learning and enrich their academic, linguistic, and socio-cultural experiences.

Establishing an environment that is conducive to learning, as well as supporting students’ academic and social enculturation, is not limited to the teacher creating a warm interpersonal atmosphere in the classroom, although it is certainly an integral part of a successful teaching-learning venture (e.g., Fassinger, 2010; Frisby & Martin, 2010; Frisby & Myers, 2008; Shvidko, 2018). Additionally, the structure of the course, including its syllabus, materials, projects, and activities, may stimulate students’ successful socialization to their local academic and socio-cultural community, which can ultimately promote their learning.

Many international students on university campuses are also second language (L2) learners. Therefore, their adaptation to a new setting is inseparable from their language socialization (Duff & Talmy, 2011; Morita, 2004; Willett, 1995). In the field of applied linguistics, L2 socialization is defined as “the acquisition of linguistic, pragmatic and other cultural knowledge through social experience [which] is often equated with the development of cultural and communicative competence” (Duff, 2010a, p. 427). By this definition, L2 learning is viewed through a social lens, or in other words, through the examination of learners’ participation in social interaction with other members of the environment (either instructional contexts or naturalistic settings), through which learners develop an appropriate level of competency, enabling them to successfully function in the target community.

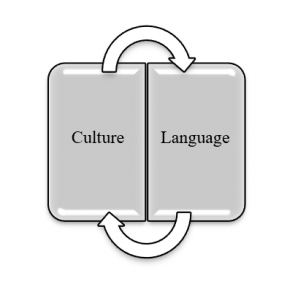

Furthermore, as seen from this definition, during the process of a learner’s socialization, linguistic and cultural competencies facilitate each other. On the one hand, language is a tool for access to resources available in a particular community, comprised of the “knowledge of values, practices, identities, ideologies, and stances” (Duff & Talmy, 2011, p. 98). On the other hand, language learning appears to be a result of increased access to the resources and local conventions—that is, the more exposure learners have to the resources, the more linguistic forms they acquire. Thus, from the language socialization perspective, linguistic and cultural knowledge are interdependent components, as illustrated in Figure 1:

Accordingly, the process of L2 socialization can be viewed from two perspectives: (1) socialization through language; and (2) socialization to language (Ochs & Schieffelin, 1984). As seen, language is as a possessor and creator of cultural meanings and a provider of access to resources, but it is also a developing entity. In other words, as students increase their L2 proficiency, they gain a wider range of opportunities to use various social, cultural, and educational capitals provided by the target community. At the same time, learners’ participation in social and cultural activities in their target communities increases their opportunities to communicate in their L2, thus allowing them to develop more sophisticated linguistic forms.

I teach at the Intensive English Language Institute (IELI), which is part of the Department of Languages, Philosophy, and Communication Studies at Utah State University. The program is designed specifically for English language learners, with the aim of helping students develop their linguistic and academic skills and intercultural competence. IELI students come from various linguistic, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds, and with different levels of English language proficiency. As a supporter of L2 socialization theory (Duff & Talmy, 2011; Watson-Gegeo & Nilsen, 2003), I try to expose my students to a variety of socio-cultural information, hoping that as they increase their proficiency in English, they will strive to obtain a wider range of opportunities to use various social and cultural resources offered by the university and the local community. Many of my students have been in the United States for only a few months, and for some of them, being in college is a brand-new life experience. Therefore, when I develop my courses, I strive to implement materials that will allow students to interact with the social and cultural affordances available at the university and in the community.

The Example of Promoting L2 Socialization through a Course Project

In Fall 2017, I taught IELI 2330 – “Spoken Discourse and Cross-Cultural Communication.” This class is designed for students of the intermediate level of English proficiency and geared toward helping them develop interpersonal communication skills through small-group work interactions. In this course, students also have the opportunity to interact with American classroom assistants (undergraduate students at USU) who help them to accomplish academic tasks assigned throughout lessons, and to facilitate group interaction. In the course described below, there were 15 international students from several countries, including China, Jordan, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia, and four undergraduate classroom assistants.

Following the principle of the interdependence of language and culture in L2 socialization described earlier, I designed the course as follows. There were five units in the course: Building a Learning Community, Education, Globalization, The Environment, and Fashion and Styles. Each unit lasted three weeks.

Week 1: Background

During the first week, the students built some background knowledge about the topic. They also read or listened to passages that stimulated their thinking about the focal topic and provided them with new vocabulary.

Week 2: Zooming In

During the second week, the students were introduced to the project of the target unit, which involved the investigation of a local socio-cultural context related to the topic of the unit. Thus, the focus of each unit was narrowed to one particular contextual level. For example, for Unit 1, the students were asked to create a group profile, which gave them the opportunity to get to know members of their group and others in the class (i.e., group level). For Unit 2, the students gave a formal PowerPoint group presentation on one of the following types of resources available to them on USU’s campus: social and cultural, academic and professional, athletic and recreational, and student services (i.e., university level). The project for Unit 3 took the students to the next contextual level—the city—by requiring them to prepare and lead a discussion on the topic “The city of Logan in the era of globalization.” Unit 4 gave the students the opportunity to expand their knowledge about the national parks in Utah, as they worked on a poster presentation on one of Utah’s five national parks (i.e., state level). For Unit 5, the students had to present several outfits that people in the U.S. could wear in certain social situations, including church, first date, wedding, sporting event, and dance party (i.e., country level).

Week 3: Project Week

Finally, during the third week of a given unit, the students worked on and presented their projects. A summary of the units, projects, and project genres is given in Table 1.

| Unit | Project | Project Genre |

|---|---|---|

| Building a Learning Community | “Our Group Profile” | Varies (e.g., skit, group portrait, photo slideshow) |

| Education | “Exploring USU” | Formal PowerPoint Presentation |

| Globalization | “The city of Logan in the Era of Globalization” | Leading a Discussion |

| The Environment | “Utah’s National Parks” | Poster Presentation |

| Fashion and Styles | “The American Fashion Show” | Narrated Fashion Show |

As seen in Table 1, the described course also aimed at giving the students the opportunity to create projects in various genres: a group profile, a PowerPoint presentation, a discussion, a poster, and a narrated fashion show. Therefore, in addition to mastering the skill of working in a group, the students were also able to practice various communicative and rhetorical strategies related to each genre.

Below I describe how the course projects facilitated students’ socialization through and to the target language.

Socialization through Language

The projects were created with the purpose of giving students the opportunity to socialize to the environment around them through completing meaningful authentic tasks in the target language. As seen from the description above, each project required the students to gather information about one particular level of their local academic and socio-cultural environment—their own group, campus, city, state, and nation—and become acquainted with it. Because all projects involved interactional practices that allowed the students to communicate not only with each other and their classroom assistants, but also with other people outside the classroom, students were offered a rich opportunity for socialization.

The process of socialization through language started with the classroom environment, when the students were working on the first unit of the course. I envisioned this unit as a way of helping the students get to know each other and develop collaborative strategies in their teams. By creating their group profiles, the students were learning about each other’s backgrounds, hobbies, interests, and learning styles, while planning and organizing their work together and developing their group creativity. A sense of community was evident when the students were presenting their profiles in front of the class. As a teacher, I felt that the scene was set for there to be effective work throughout the semester.

While working on the project for Unit 2, the students received another opportunity for socialization through language. The unit assignments exposed them to plentiful resources that Utah State University offers to help students develop their academic, professional, and social skills, as well as to stay healthy—both physically and emotionally. The students became familiar with the resources offered by the USU library, writing center, Academic Success Center, Information Technology, Disability Resource Center, and Counseling and Psychological Services, to name a few. For many students, this was their first encounter with USU clubs, organizations, programs, events, services, recreational facilities, outdoor programs, and volunteering opportunities, and the students found it a very helpful experience.

The project for Unit 3 helped the students to become acquainted with the city of Logan and to realize that even in this relatively small town, they can see products, businesses, and social and educational opportunities that demonstrate the effects of globalization. For example, for one of their homework assignments, which the students seemed to particularly enjoy, they had to go to a local grocery store and take pictures of the products that represented the concept of globalization. The students found products that were familiar to them, either because similar products of American brands were sold in their countries (e.g., various kinds of chips, soda, and chocolate) or because they were manufactured in their countries and exported to the U.S. For many students, this unit was an eye-opening experience as they realized that nowadays, even in small towns such as Logan, it is possible to see the interconnectedness of economies, businesses, cultures, and education systems. By accomplishing the unit assignments, the students also socialized to the local environment of the town.

Another opportunity for socialization through language was provided in Unit 4, which exposed the students to the beauty of the state of Utah. As an avid hiker, I could not pass up the chance to introduce my students to the parks as places for hiking, camping, and other outdoor opportunities. Thus, to expose the students to the variety of landscapes and natural resources available in each park, I discussed all of Utah’s national parks during the introduction lesson to this unit and showed them some photos, videos, and maps. However, because the final project of the unit was done under the topic “The Environment,” I wanted the students to mostly focus on exploring the environmental features of the parks. Therefore, as the students were creating a poster for the park assigned to their team, they primarily worked with the materials related to park’s historical facts and environmental factors, including vegetation, wildlife, and governmental efforts to protect the park’s ecosystem. Overall, this unit provided the students with a great deal of new information about the system of national parks in the U.S. At the same time, for many students in my class, this was their first semester in the U.S., and quite understandably, they were not aware of the various recreational opportunities available in Utah. Therefore, this project expanded the students’ knowledge about the natural resources offered in the state.

The final unit of the course started with the discussion of why American people tend to dress casually. To help the students socialize to this cultural phenomenon, I asked them to read an article offering a historical perspective by discussing several milestones that marked this “casual turn.” This article was illuminating in many ways, and certainly afforded the students a better understanding of the roots of clothing casualness in American society. While preparing for the project of the unit—the narrated fashion show, for which the students had to create and present an outfit for a particular social setting, the students collected information from various sources, including searching through the web, consulting with their classroom assistants, speaking with other people (e.g., friends and roommates), and making informal observations outside the classroom. Cultural differences were most apparent in this unit, as the students realized that people’s views of what should be considered appropriate to wear in particular social situations in their home countries and the U.S. may not always align. The American classroom assistants provided a lot of useful information to the students as well. For example, one of the assistants explained that a female wedding guest should not look better than the bride. Other assistants shared helpful information about their own clothing preferences in relation to various social occasions. As a result of this project, the students became better acquainted with a range of clothing styles in the U.S. and began to better understand what kinds of clothes Americans wear in different social situations.

Thus, while working on the meaningful tasks geared toward practicing their oral communication skills, the students were also becoming familiar with several levels of their academic and socio-cultural environment: their own classroom, the university, the city, the state, and the country. Although I do not claim that the process of socialization was complete or equally effective for all students in the class, I do believe rich opportunities for this process were provided to the students, and based on my observations, were used by everyone in the class.

Socialization to Language

Along with giving the students the opportunity to learn about various levels of their academic and socio-cultural environment, the course was also designed to help them socialize to the target language. Thus, for each unit of the course, the students had to work with thematic videos, discuss listening and reading passages, interview people outside the classroom, and complete various assignments in class. As the students worked on their course projects and interacted with each other, with their classroom assistants, and with other people outside the classroom, they were acquiring new lexical items and grammatical structures. It can be argued, therefore, that through these interactional practices and meaningful tasks, the students were actively socializing to the target language.

This socialization to language started with Unit 1. While working on this unit, the students were asked to create a list of group values and behaviors that could be agreed upon by everyone in the group. First, the students had to choose the top three values from a given list (or they could add their own) that they believed would be important for their group. The list included several words that were new to many students, such as accountability, insightfulness, ambition, open-mindedness, equality, and curiosity. Then, for each of the three group values, the students discussed two appropriate behaviors that supported this value (such as respecting others’ opinions), as well as two inappropriate behaviors that did not support this value (such as interrupting others). At the end of this activity, each group developed a kind of contract that included the list of values and behaviors that everyone agreed to follow. At the same time, during the process of negotiation, the students were also actively learning new English vocabulary.

While working on Unit 2, we discussed several issues related to intercultural differences in academic settings, such as interacting with college professors, receiving grades on course assignments, collaborating with peers, and participating in class discussions. The students were presented with several case studies that they discussed with each other and their classroom assistants. Reflecting on the cases and discussing them in class allowed the students to learn new vocabulary. Another topic discussed in the unit, which related particularly to the students’ academic and cultural status, was fitting in on campus. During the lesson devoted to this topic, the students worked with an authentic listening passage from National Public Radio, rich with new vocabulary items that the students then used in subsequent discussions on the topic.

A similar exposure to new vocabulary was offered to the students through the discussions and readings of Unit 3 that helped them learn such words as import, consumer, investigate, overseas, label, and produce. In addition, while preparing to lead a group discussion—the final project of the unit—the students learned how to present an argument and support it with convincing pieces of evidence. The design of the project gave the students a chance to formulate their own opinion and support it with examples. In other words, whereas the students were given the general topic for the project—the city of Logan in the era of globalization—they were asked to form their own argument related to this topic: that is, whether or not they believed Logan was experiencing the effects of globalization. Each group was asked to investigate a certain category in relation to this topic: food (local restaurants and food in grocery stores), social life (Logan’s clubs, organizations, social events and activities), businesses (companies and stores), and education and religion (churches, schools, and educational programs). The objective was to answer the question: What are some effects of globalization on the city of Logan when it comes to this category? The opportunity for language development in this project was ample –especially in final group discussions, during which the students had to present their argument, support it with collected data, promote a group discussion, and answer questions from classmates.

Another opportunity for socialization to language was given in Unit 4, which was particularly rich in new vocabulary items. As the students were working on the project for this unit—creating a poster about one national park in Utah—they encountered a number of words specific to the topic “the environment.” Some of these words included flora, fauna, ecosystem, wildlife, waste, habitat, conservation, revitalization, and preserve. More vocabulary items were discovered in the readings about the national parks, which the students worked with while creating their posters. Many of these words were highly specialized terms, such as hoodoos, erosion, sandstone, plateaus, and perennials, yet they allowed the students to talk knowledgeably about the topic.

Similarly, Unit 5 contained a great deal of specialized vocabulary, mostly related to clothes and styles. In order to create a narrated fashion show for the final project of this unit, demonstrating several outfits that people in the U.S. would wear in diverse social occasions, the students not only had to learn various names of clothes but also adjectives describing styles and outfits, such as casual, conservative, dressy, elegant, sloppy, sporty, stylish, and trendy. It was rewarding to see that many students were using these words during their presentations.

Along with the vocabulary specific to each topic of the unit, the students were also introduced to the phrases necessary for successful interaction in their groups. For example, they learned phrases for several speech acts, including expressing their opinion (e.g., “The way I see it is…”; “Wouldn’t you say that…?”; “As I see it…”), supporting their opinion (e.g., “I think this because…”; “It’s a bit complicated, but I think…”; “The reason is…”), agreeing (e.g., “That’s exactly how I feel”; “You have a point there”; “I was just about to say that”), disagreeing (e.g., “I agree with you in some ways, but…”; “Here’s another way to think about it…”; “True, but how about…?”), and encouraging active participation (e.g., “That’s my opinion. How about the rest of you?”; “Any thoughts on what I just said?”; “Any other opinions?”). In addition to learning the grammatical structures of these phrases, the students were also becoming familiar with the importance of the cultural appropriateness of each of these speech acts with reference to academic settings.

Thus, while promoting students’ cross-cultural interaction and their participation in various activities in and outside the classroom, the course projects also aimed at increasing students’ opportunities to communicate in their L2, thus allowing them to develop more advanced linguistic forms. From this perspective, these projects and assignments encouraged students’ socialization to the target language.

Limitations

The course projects described above were designed with the aim of helping students become more familiar with the academic, social, and cultural resources in their local environment through completing a series of authentic linguistic assignments (i.e., socialization through language), as well as promoting their language development by having them explore these resources (i.e., socialization to language). The development of students’ oral communication and linguistic skills (socialization to language) was evident throughout the semester and evaluated by both my informal observations and by the use of rubrics developed for each project of the course. However, the formal assessment of the degree to which the students became socialized to their local environment (socialization through language) was beyond the scope of this study. This is not to say that as the instructor, I failed to observe students’ growing sense of enthusiasm and motivation, which resulted from their increased familiarity with various resources offered in their surroundings (including their university, city, and state). I nevertheless acknowledge the importance of triangulating these informal observations and anecdotal evidences by assessing learner socialization through a more rigid research methodology. From this perspective, this study offers a promising area for future research.

Suggestions

Although I fully realize that the presented design may be different from other university courses, I believe faculty can incorporate the elements of socialization into their syllabi to help language learners advance their language proficiency and become more integrated in their local academic and socio-cultural environments. Such efforts do not necessarily have to result in full-fledged projects, as demonstrated above. Rather, the implementation of various features of local environments in a course syllabus could have important implications for students’ language socialization. Below, I provide several suggestions for instructors on how to promote such socialization.

Guest speakers

Nowadays, many universities offer a wide range of programs, services, and resources that are designed to help students succeed in their studies and social life. Instructors can invite representatives of these programs and services to their classes to expose students to opportunities that can improve their academic and social experience at the university. Such visits can be arranged at different times in the semester: at the beginning of a semester (e.g., a representative from a writing center, a library, or student organizations), in the middle of a semester (e.g., a representative from counseling services or volunteering organizations), and toward the end of a semester (e.g., a representative from an academic success center or a career center).

Surveys on campus

Instructors can also ask students to conduct small-scale surveys on campus to gather data either for a subsequent classroom activity or for their own research projects. Students can informally ask others on campus (e.g., other students, faculty or staff members) to express their opinion or provide information on certain topics. Such surveys can be implemented in virtually any course, regardless of the discipline.

Library tours

University libraries provide some of the richest resources and materials to help students succeed academically. Unfortunately, some students –particularly those from different cultures—may not fully utilize libraries in their studies. Instructors can organize library tours at the beginning of a semester to help students become familiar with the range of resources and materials offered by libraries and feel more comfortable using them in their academic activities. While tours led by a library staff member can be particularly resourceful, self-guided tours may benefit students as well.

Photo scavenger hunts

As most students enjoy using their smartphones, teachers can implement photo scavenger hunts that would require students to use university and community resources. For example, instructors can provide a list of titles and call numbers of books from a university library and ask students to locate them on the library shelves and document their findings by taking photos. Students can also be asked to take photos of various objects on campus or in the community that represent certain concepts discussed in the course (e.g., globalization, an effective marketing technique, certain architecture designs, engineering projects).

Classroom activities and homework assignments

There are numerous ways to implement local resources in classroom activities and homework assignments: from exploring the university website with a particular focus in mind, to writing a summary about a certain program on campus, to attending a university-sponsored event, to conducting an interview with another professor or a university staff member. Along with the particular pedagogical objectives (determined by the instructor) upon which each of these activities and assignments focus, they can also help promote students’ language development, as well as cultivate their desire to become an integral part of their academic and socio-cultural community.

Conclusion

Second language learning is inseparable from the social environment in which the learning takes place, whether it is a natural setting or a classroom. In this environment, learners acquire new forms of being, including “a repertoire of linguistic, discursive, and cultural traditions” (Duff & Kobayashi, 2010, p. 79), which allow them to “survive and prosper” (Atkinson, 2011, p. 144) in this new ecology. In this process, teachers play a crucial role (Kanagy, 1999, Morita, 2004; Seror, 2008; Zappa-Hollman, 2007), by either providing or withholding “opportunities for meaningful enculturation” (Duff, 2010b, p. 181). I believe teachers are well positioned to provide necessary support and opportunities for newcomers—international students on our campuses—in order to help them develop linguistic, pragmatic, and cultural competencies, so they can successfully participate in a wide range of activities available in their local academic and socio-cultural communities.

I encourage university instructors to be conscientious about pedagogical practices, strategies, and approaches used in their classrooms, because they influence not only students’ classroom participation and success in the course, but also their socialization—in either a positive or a negative way.

References

Andrade, M. S. (2006). International students in English-speaking universities: Adjustment factors. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(2), 131-154.

Atkinson, D. (2011). A sociocognitive approach to second language acquisition: How mind, body, and world work together in learning additional languages. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 143-166). Hoboken, NJ: Taylor and Francis.

Baker‐Smemoe, W., Dewey, D. P., Bown, J., & Martinsen, R. A. (2014). Variables affecting L2 gains during study abroad. Foreign Language Annals, 47(3), 464-486.

Bista, K., & Foster, C. (Ed.). (2016). Campus support services, programs, and policies for international students. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Duff, P. (2010a). Language socialization. In: N. Hornberger & Lee McKay (Eds.). Sociolinguistics and language education (pp. 427-452). Multilingual Matters, UK.

Duff, P. (2010b). Language socialization into academic discourse communities. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 30, 169-192.

Duff, P. & Kobayashi, M. (2010). The intersection of social, cognitive, and cultural processes in language learning: A second language socialization approach. In: R. Batstone (Ed.), Sociocognitive perspectives on language use and language learning (pp. 75-93). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Duff, P. A., & Talmy, S. (2011). Language socialization approaches to second language acquisition. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 95-116). Hoboken, NJ: Taylor and Francis.

Fassinger, P. A. (2000). How classes influence students’ participation in college classrooms. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 35(2), 38-47.

Frisby, B. N., & Martin, M. M. (2010). Instructor–student and student–student rapport in the classroom. Communication Education, 59(2), 146-164.

Frisby, B. N., & Myers, S. A. (2008). The relationships among perceived instructor rapport, student participation, and student learning outcomes. Texas Speech Communication Journal, 33, 27-34.

Hsieh, M. H. (2007). Challenges for international students in higher education: One student’s narrated story of invisibility and struggle. College Student Journal, 41(2), 379-392.

Kanagy, R. (1999). Interactional routines as a mechanism for L2 acquisition and socialization in an immersion context. Journal of Pragmatics, 31, 1467–1492.

Lee, C. S., Therriault, D. J., & Linderholm, T. (2012). On the cognitive benefits of cultural experience: Exploring the relationship between studying abroad and creative thinking. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26(5), 768-778.

Milian, M., Birnbaum, M., Cardona, B., & Nicholson, B. (2015). Personal and professional challenges and benefits of studying abroad. Journal of International Education and Leadership, 5(1), 1-12.

Morita, N. (2004). Negotiating participation and identity in second language academic communities. TESOL Quarterly, 38(4), 573-602.

Ochs, E. & Schieffelin, B. (1984). Language acquisition and socialization. In: R. A. Schweder & R. A. LeVine (Eds.). Culture theory: essays on mind, self, and emotion (pp. 276-320). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Poyrazli, S., Kavanaugh, P. R., Baker, A., & Al‐Timimi, N. (2004). Social support and demographic correlates of acculturative stress in international students. Journal of College Counseling, 7(1), 73-82.

Shvidko, E. (March, 2014). How well do we utilize campus resources to help L2 writers? TESOL SLW News. Retrieved from: http://newsmanager.commpartners.com/tesolslwis/issues/2014-03-05/5.html

Shvidko, E. (2018). Writing conference feedback as moment-to-moment affiliative relationship building. Journal of Pragmatics, 127, 20-35.

Seror, J. (2008). Socialization in the margins: Second language writers and feedback practices in university content courses. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Shapiro, S., Farrelly, R., & Tomaš, Z. (2014). Fostering international student success in higher education. Alexandria, VA: TESOL Press.

Watson-Gegeo, K. A., & Nielsen, S. (2003). Language socialization in SLA. In: C. Doughty & M. Long. (Eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 155–177). Oxford: Blackwell.

Willett, J. (1995). Becoming first graders in an L2: An ethnographic study of L2 socialization. TESOL Quarterly, 29(3), 473–503.

Zappa-Hollman, S. (2007). Academic presentations across post-secondary contexts: The discourse socialization of non-native English speakers. Canadian Modern Language Review, 63, 455-485.