Semester in the Parks

Jacqualine Grant, Ph.D. and John MacLean, Ph.D.

Abstract

High-impact educational practices (HIP) such as Common Intellectual Experiences (CIE) enhance student engagement and positively affect student learning. At Southern Utah University we created a new HIP-focused program to enrich our students and faculty: Semester in the Parks (SIP). Students lived outside of Bryce Canyon National Park in the gateway community of Bryce Canyon City while they worked for Ruby’s Inn Resort and learned about the national parks. Faculty commuted to this off campus venue and redesigned their courses to incorporate national parks thinking and experiential learning opportunities. The CIE of a national parks-focused semester enhanced student engagement and developed the pedagogical ability of faculty. Program assessment revealed positive gains in student and faculty self-report measures but also identified the need for other assessment tools and comparison groups. We conclude that CIE, even those set in nontraditional classroom locations, have great potential to enhance student growth and faculty professional development.

Introduction

High-Impact Educational Practices (HIPs) are undergraduate educational experiences that enhance student engagement (Kuh et al. 2005) and positively affect student learning and development (Brownell and Swaner, 2009; Kilgo et al. 2015). HIPs range from narrowly defined opportunities, such as Undergraduate Research Experiences, to loosely defined activities, such as Common Intellectual Experiences (Kuh, 2008). Because of their flexibility, Common Intellectual Experiences (CIEs) are readily adapted for university programs that are focused on student recruitment and academic enrichment. CIEs can be horizontally integrated within a semester or vertically integrated over the course of a student’s career, but are defined by their intentional design as a strategically linked group of experiences (University of Colorado Denver, n.d.). Single semester CIEs are often built around a shared “big idea” or unifying concept, which makes CIEs the ideal HIPs for multi-course, interdisciplinary programs.

In 2015, we were presented with an opportunity to develop a new HIP-focused program at Southern Utah University (SUU): Semester in the Parks (SIP). Of the ten HIPs identified by the Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U), we selected CIEs as our framework because all courses in the SIP program were linked by a unifying theme: America’s National Parks. The SIP program resulted from several years of brainstorming about how to create a curriculum that embodied experiential, engaged, and integrated learning while also capitalizing on SUU’s geographic surroundings and fostering SUU’s fantastic community partnerships. What follows is our description of how SIP developed, how it contributed to teaching excellence on our campus, and what we have learned from the program through student evaluations. We conclude with descriptions of challenges such a program faces during its implementation, as well as recommendations to consider as other institutions develop their own CIEs.

What is the Semester in the Parks Program?

In 2015, SUU began serious talks about how to commemorate the Centennial Celebration of the National Park Service’s creation in 1916. One longstanding aspiration had been to engage SUU students in experiential learning opportunities at Bryce Canyon National Park (BCNP). At about the same time, we learned that SUU students may be able to help meet a need of Ruby’s Inn Resort, one of our most important community partners. Ruby’s Inn Resort comprises a major part of Bryce Canyon City, the gateway community to BCNP. The resort employs several hundred seasonal workers during the summer, and many come from international locations. Our partners at the resort expressed the desire to employ more SUU students, especially in the fall season when many of the international workers leave. Ruby’s Inn Resort and the Centennial’s need for SUU student workers created the perfect opportunity for an innovative academic program that would begin in Fall 2016.

The SIP program allowed students to live and work at Ruby’s Inn Resort for one semester as they earned a full credit load through field-based courses taught by SUU faculty, who each commuted to BCNP approximately once per week. Students paid their regular tuition, plus a fee of $1200 for the Fall 2016 program and $1500 for the Fall 2017 program. Their fees helped to fund five excursions to other national parks, monuments, and lands each semester. These weekend field excursions complemented their coursework and provided experiential learning opportunities.

Courses were delivered to students as a once-per-week, three- to four-hour session, which is comparable to a typical on-campus class encompassing three one-hour weekly periods. However, all courses were completely redesigned to take advantage of the national park and its surroundings. Faculty were encouraged to teach field-based lessons whenever possible, but when weather forced classes to go indoors, a partnership with the Bryce Canyon Natural History Association allowed them to use the High Plateaus Institute (HPI) Building. The HPI was the first visitor center at the park and now serves as an educational building administered by the Bryce Canyon Natural History Association.

Programmatic Logistics of SIP

Four guiding principles helped the leadership team design the SIP program:

- Help students gain an experiential education in alignment with SUU’s mission

- Help faculty gain professional development by working together to create innovative ways of delivering content that are informed by the national parks settings

- Facilitate students and faculty working with community partners for the mutual benefit of all parties

- Allow students and faculty from any discipline to participate

The SIP program was housed in SUU’s Provost Office for one year until moving to its permanent home in the School of Integrative and Engaged Learning. Each fall semester, the Provost’s Office disseminated a description of the program and a call for faculty applications that was open to the entire campus. Faculty applications were required to show how existing courses would be enhanced if taught at BCNP instead of at SUU. The leadership team reviewed the faculty applications and selected a suite of courses they deemed appropriate for the next fall semester. To ensure that students and faculty from across disciplines could participate, the offerings were almost exclusively General Education (GE) courses. Faculty participants earned a $1500 stipend to compensate them for time spent in the spring semester biweekly planning meetings. The program also reimbursed travel. Funds were provided by the Office of Academic Affairs to support SIP as an academic innovation that could raise the profile of SUU on a national scale.

The first year of SIP was built around GE courses that complemented each other and offered unique perspectives about national parks. The courses also allowed for integrated teaching and learning opportunities. Faculty development was fostered by the selection of faculty with a mix of field expertise. The Fall 2016 SIP program offered 16 credits in the following courses: BIOL 2500 Environmental Biology (3 GE credits in Life Science), COMM 1010 Introduction to Communication (3 GE credits in Humanities), GEO 1050/1055 Geology of National Parks (4 GE credits in Physical Science), LM 1010 Information Literacy (1 GE credit in Integrated Learning), ORPT 2040 Americans in the Outdoors (2 elective credits), and UNIV 3500 Interdisciplinary Engagement (3 elective credits).

Five out of the six faculty who taught in the 2016 SIP program reapplied for Fall 2017, which helped them to build on the significant effort of course redesign in 2016. One course (COMM 1010) was replaced with two GE courses (CJ 1010 and HIST 1700), and ORPT 2040 increased from two to three credits as part of its transition to a GE course. UNIV 3500 was reduced to one credit to cap the Fall 2017 SIP program at 18 credits, 17 of which were GE.

After the suite of courses was selected, the leadership team advertised the SIP program to students on and off of SUU’s campus. SIP targeted between 15 and 20 second-year college students, to obtain the desired student maturity level and to attract students in need of GE requirements. The Academic Coordinator and Program Director interviewed each applicant in face-to-face or video-conferencing meetings. SIP accepted 12 students at the freshmen, sophomore, and junior level for both years. Both cohorts of students included a high percentage of Utah residents, as well as students from other universities and countries.

In southern Utah, the fees required by this program can be an obstacle to student participation. Therefore, we worked with Ruby’s Inn Resort to provide employment opportunities and low-cost employee housing for our students. Because many SUU students struggle to find employment in our rural economy, the guaranteed employment at Ruby’s Inn also served as a recruiting tool. Ruby’s Inn Resort employed students in their housekeeping department for approximately 20 hours per week, which allowed them to earn back most of the fees related to the SIP Program. Students typically worked on weekday mornings before attending class in the afternoon.

Learning Objectives for the SIP CIE

One set of SIP learning objectives was adopted from SUU’s Outdoor Engagement Center (OEC) because of its connection to public lands and outdoor education. For this set of objectives, both students and faculty were expected to strengthen their: (1) ability to be competent in the outdoors; (2) practice of environmental stewardship; (3) knowledge of the cultural and natural world; (4) academic/professional abilities; (5) skills in tackling challenging, unscripted problems; and (6) self-confidence. These objectives transcended the content and skills that traditional, classroom-based courses cover. SIP focused on how the combination of courses, field excursions, employment, and community-building activities would enrich students’ lives in an immersive and life-changing experience at BCNP.

Beyond BCNP, visits to other national parks and public lands helped connect students to the proposed learning objectives. For instance, in Fall 2016, students visited what would soon become Bears Ears National Monument (under revision in 2018), Cedar Breaks National Monument, Capitol Reef National Park, Great Basin National Park, Zion National Park, Pipe Spring National Monument, and Grand Canyon National Park. Fall 2017 field excursions included Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Gold Butte National Monument, and Dixie National Forest. These expeditions added to students’ growing perspectives of the complex interactions between humans and the lands around us. The field trips became an integral component of the educational experience because of their ties to SUU’s essential learning outcomes and the OEC’s learning objectives.

Integration in SIP

One benefit of CIEs is the opportunity for integration across disciplines. SIP encouraged students to integrate course material through two mechanisms. In 2016, students collaboratively wrote an e-book in answer to the question: Why do we have national parks? Students incorporated concepts and content from all five courses in their answer. In 2017, SIP used a different approach: integration around themed weeks. Each week’s theme corresponded with one of National Geographic’s “Top Ten Issues Facing National Parks” (National Geographic, 2010). All of the students’ courses investigated the weekly theme from their own perspectives, which helped students discover the complicated and interrelated nature of the national parks and their surroundings. Sometimes integration was deliberate, as during the week when the theme was “Adjacent Development”. During this week, students visited the Coal Hollow Mine with biology and geology instructors. The coal mine is less than 12 miles from the BCNP boundary, and it provided a lesson about the geological origins of coal, the biological ramifications of coal mining operations, economic drivers of the coal industry, and potential environmental effects on BCNP. Such integrated field-based learning opportunities defined the SIP experience.

You can’t fix what you don’t measure: SIP Assessment

HIPs are established mechanisms that lead to positive outcomes for students, but because each campus has its own culture and goals, it is important to assess any HIP applications to the programs within one’s own institution (Brownell and Swaner, 2009). As SUU continues to build its brand as the University of the Parks, it aims to become a model for responsible innovation and program planning on our campus. Program-level assessment is vital to campus efforts to promote innovation through information-based decision-making. A second SIP goal is to promote faculty development –in this case, by exposure to the concepts of backward curriculum design (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005), which relies on assessment of student learning. To accomplish these goals, the SIP leadership team developed a series of survey questions (available upon request from JM) to guide program development.

The SIP leadership team identified three areas for growth in students and faculty in the program: (1) student growth related to the OEC’s learning outcomes, described above; (2) student achievement related to the university’s essential learning outcomes, which are assigned to each GE course in the SIP program; and (3) faculty professional development related to outdoor education competency. The three program-level areas for growth in students and faculty were assessed through three independent surveys approved through SUU’s Institutional Review Board (SUU IRB Approval #24-052017a).

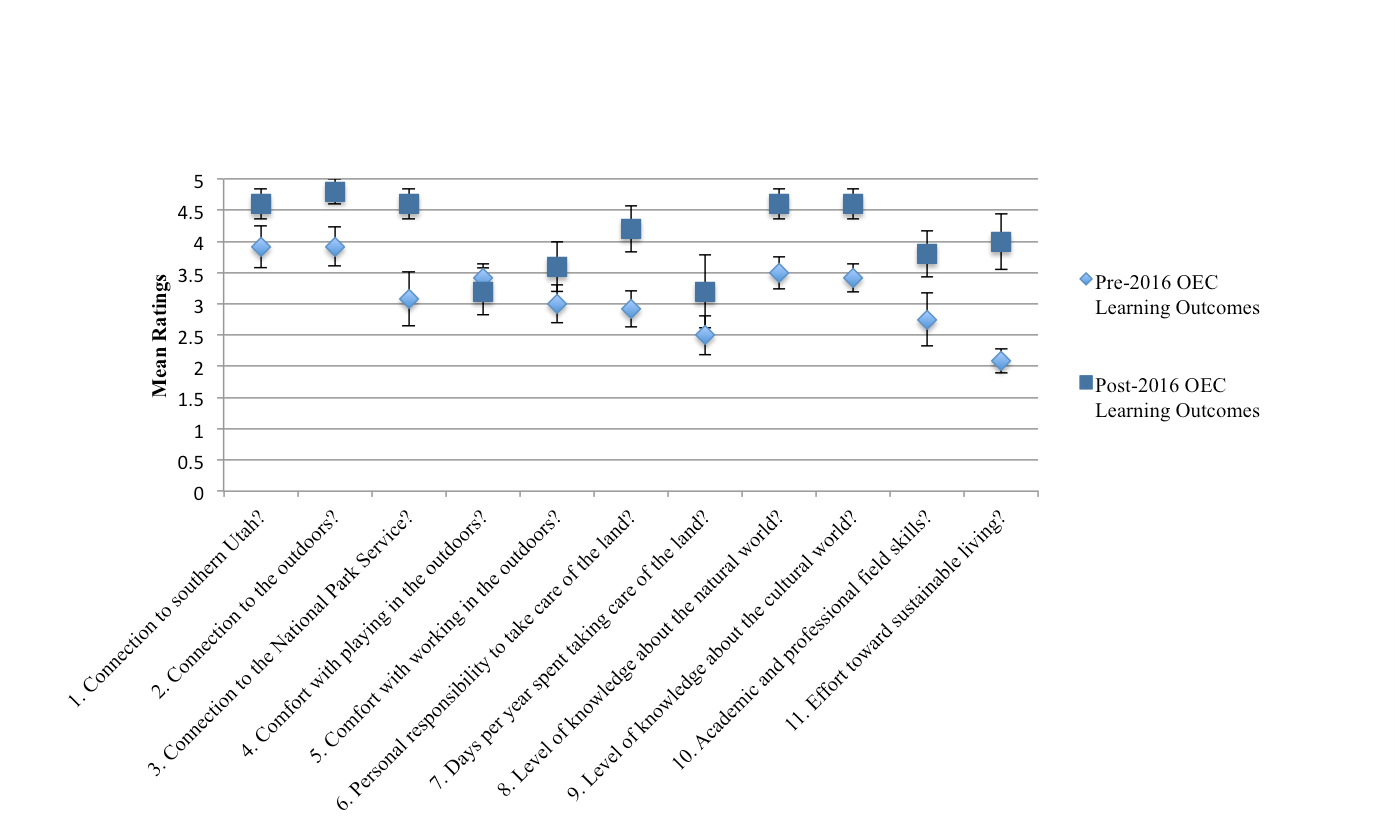

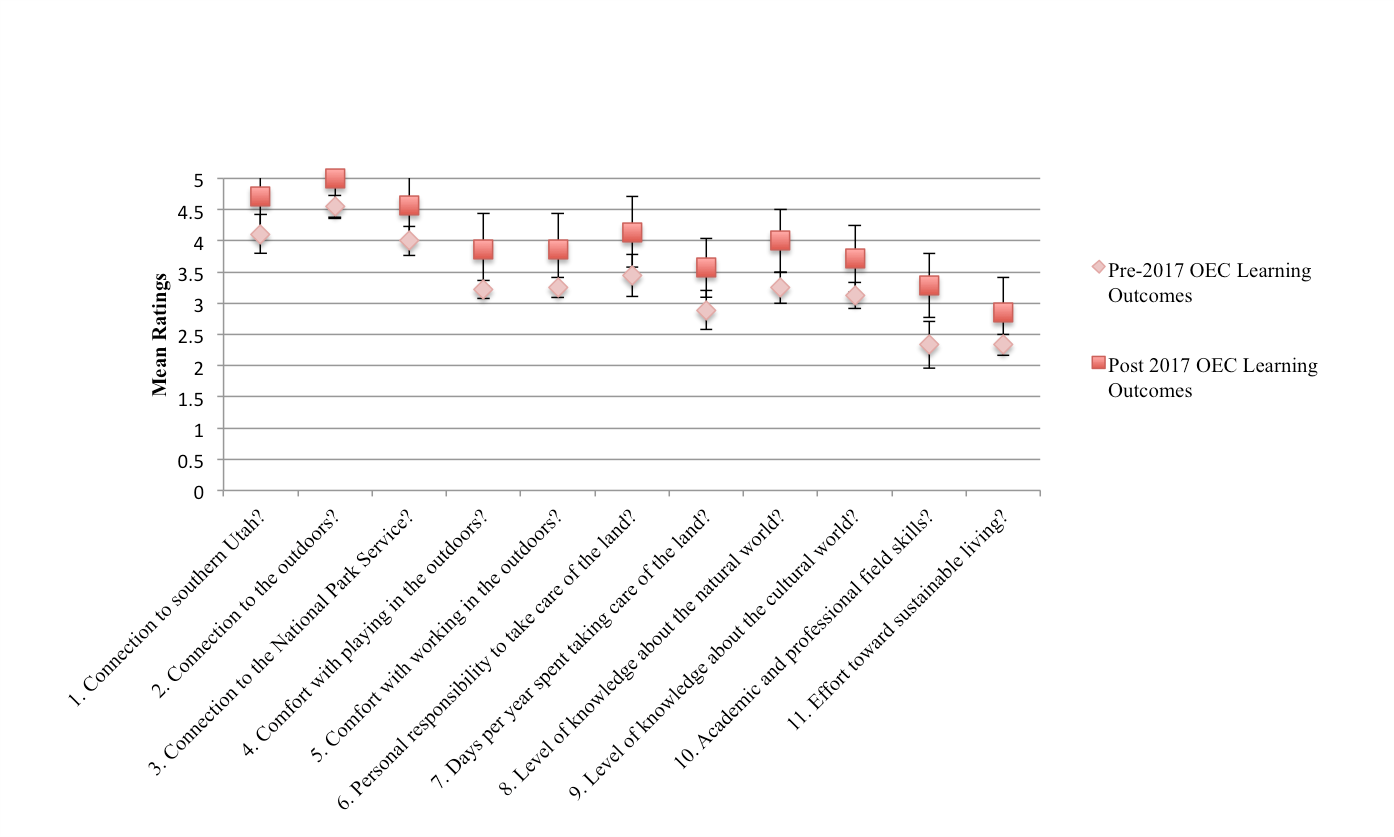

OEC learning outcomes data were collected in 2016 and 2017 to measure student growth in response to program completion. We used the same set of survey questions to measure pre- and post-semester responses of students’ self-perceptions of ability in each of eleven categories, which reflected the OEC’s learning outcomes. The SIP student OEC survey is available upon request from JM.

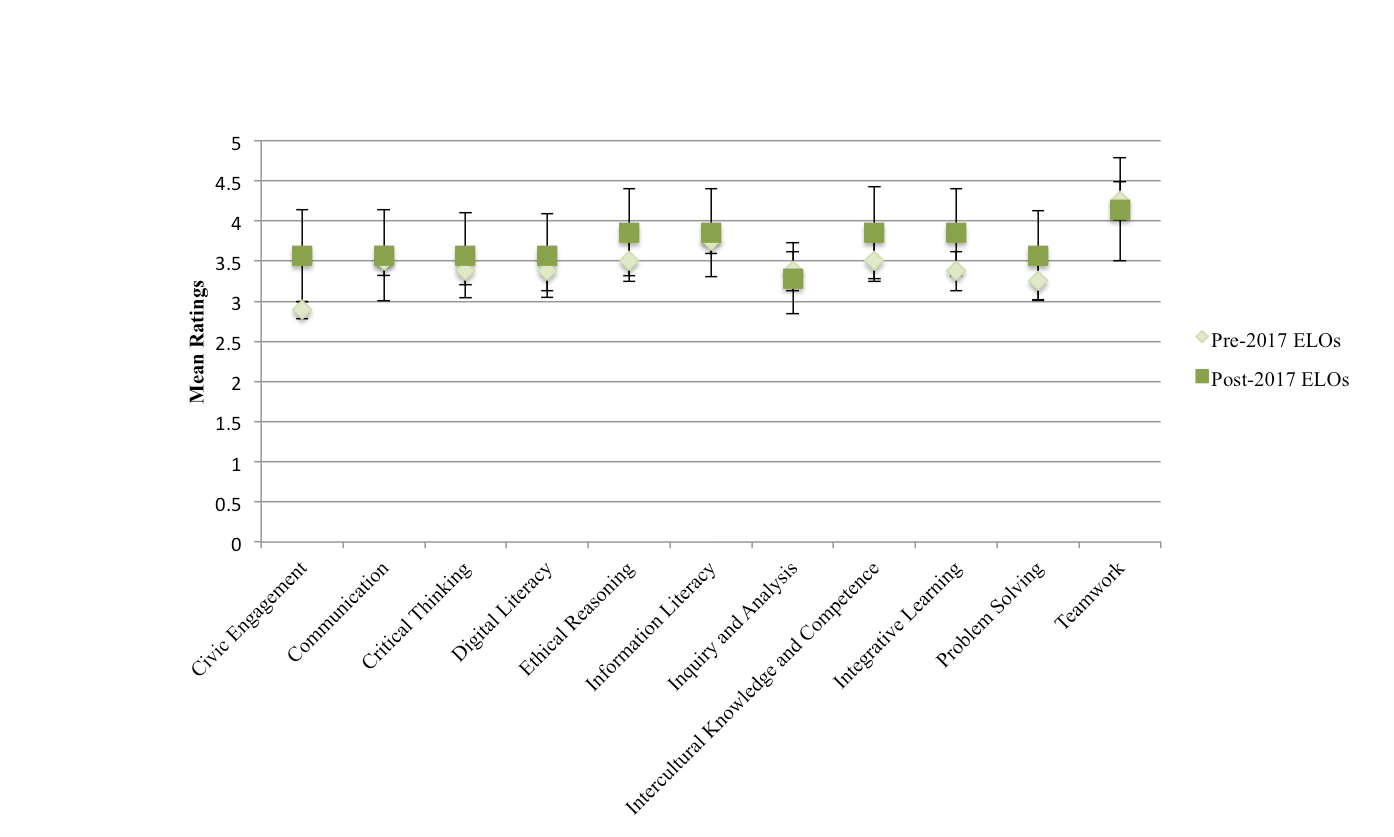

In 2017, we began to assess the essential learning outcomes (ELOs) assigned to each GE course in the SIP suite. We used a set of identical survey questions at the beginning and the end of the semester to obtain pre- and post-semester student self-reported gains in each of eleven ELOs. SUU’s ELOs are derived from ELOs defined by the AAC&U (2011). Separate assessments of each ELO were completed by each course instructor within SIP (Table 1). The SIP student ELO survey is available upon request from JM.

| ELO | Course in which ELO was emphasized |

|---|---|

| Civic Engagement | HIST 1700 |

| Communication | ORPT 2040 |

| Critical Thinking | BIOL 2500, ORPT 2040 |

| Digital Literacy | LM 1010 |

| Ethical Reasoning | HIST 1700 |

| Information Literacy | LM 1010 |

| Inquiry & Analysis | GEO 1050/1055 |

| Intercultural Knowledge | CJ 1010 |

| Knowledge of Human Culture and the Physical Natural World | BIO 2500, CJ 100, GEO 1050/1055, ORPT 2040 |

| Problem Solving | GEO 1050/1055 |

| Teamwork | BIOL 2500 |

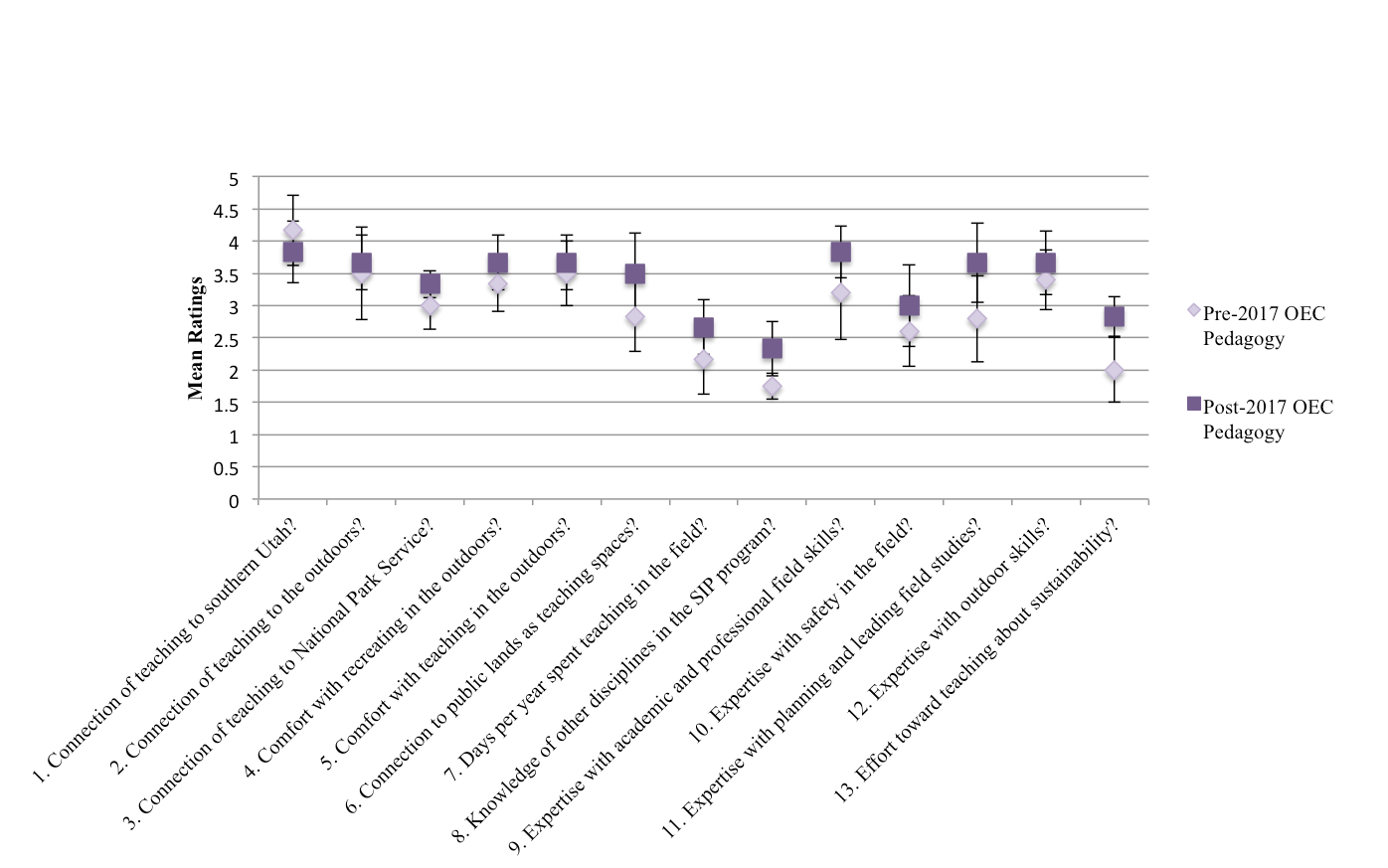

In 2017, we began to assess faculty professional development in relation to the OEC’s learning outcomes to determine how participation in SIP was affecting faculty perception of their abilities to teach in the outdoors. We used a set of identical survey questions at the beginning and end of the semester to obtain pre- and post-semester faculty self-reported gains in each of 13 areas related to teaching practices and outdoor skills and competencies. The SIP faculty OEC survey is available upon request from JM.

Results & Discussion

In 2016 and 2017, student self-reported perceptions related to OEC learning objectives trended toward positive gains in learning across eleven ELOs, with larger gains reported in the 2016 cohort than the 2017 cohort (Figures 1 and 2).

In 2016, the cohort reported a non-significant loss in the mean rating of their comfort in playing in the outdoors (ELO #4), but this loss was not observed in the 2017 cohort.

In 2017, student self-reported perceptions related to SUU’s ELO trended toward positive gains in learning across eleven ELOs (Figure 3). A non-significant loss in the mean rating of achievement was reported for two ELOs: Inquiry and Analysis and Teamwork.

In 2017, faculty self-reported perceptions related to the OEC’s ELO trended toward positive gains in development across thirteen ELOs (Figure 4). A non-significant loss in the mean rating of achievement was reported for Category #1: Connection of teaching to southern Utah.

Despite neutral to positive gains in most areas, the data indicate areas of potential improvement, which should help to inform future iterations of SIP. To improve the validity of SIP assessments, it will be important to develop other tools that do not exclusively rely on self-reporting measures. Program assessment will also be improved by the inclusion of comparison groups and by comparing with similar CIE programs at other institutions.

Conclusions

Common Intellectual Experiences (CIEs) are often loosely defined, which has hampered quantitative assessment of their impact (Kuh, 2008). However, like other High-Impact Educational Practices (HIPs), CIEs can be assessed to measure student development and program effectiveness (Brownell and Swaner, 2009; Kilgo et al. 2015). We adapted a suite of courses to suit our CIE program, Semester in the Parks, and provided a positive experience focused on recruitment and academic enrichment for our students. Our single-semester CIE was built around the unifying concept that national parks enhance our lives and our learning from multiple perspectives.

It is important to recognize several challenges encountered during the creation of formal, outdoor-based CIEs at academic institutions. First and foremost are the often conflicting perceptions of what constitutes academic rigor by student and faculty participants. Students in both offerings of SIP struggled with what they perceived as excessively high academic expectations, while faculty struggled with what they perceived as a loss of content and low academic expectations. We conclude that it is important for CIE administrators and leaders to help faculty understand how student perceptions are influenced by off-campus, outdoor-based curricula. We highly recommend that academic expectations are made explicit to all parties at the start of the program.

Other challenges to consider involve the logistics of running a field-based program without the support of a university managed field station. In this case, we were able to identify and strengthen partnerships with a local business owner, Ruby’s Inn Resort, to provide our students with housing and employment during the semester. We were also able to work with BCNP and the Bryce Canyon Natural History Association to provide all participants with classroom space during inclement weather, as well as opportunities for academic partnerships. We recommend that CIE team leaders work closely with all possible community and park partners because it is these types of partnerships that help overcome seemingly unsurpassable obstacles, such as a complete lack of teaching and living facilities.

Building student and faculty communities through Common Intellectual Experiences (CIEs) is one type of high-impact educational practice that can assist universities with student engagement, satisfaction, and retention. Students responded to our CIE program, Semester in the Parks, with positive gains in self-report metrics related to outdoor engagement and place-based learning outcomes. This should encourage other institutions to develop CIEs as a mechanism to enrich their students’ experiences. Our CIE also helped faculty develop their knowledge of other academic disciplines, their personal expertise with field skills and field studies, and their ability to integrate sustainability into the classroom. We conclude that CIEs –even those set in nontraditional classroom locations—are effective for student growth and faculty professional development.

Acknowledgments

We thank President Scott Wyatt, Provost Brad Cook, Associate Provost James Sage, and Dean Patrick Clarke of the School of Integrative and Engaged Learning for their financial support of the Semester in the Parks program. We are indebted to the following faculty contributors for their assistance with planning and teaching: Bryan Burton (2017), Anne Diekema (2016 & 2017), Briget Eastep, Kelly Goonan (2016 & 2017), Anne Smith (2016 & 2017), Jon Smith (2016), Dan Swanson (2017), and Earl Mulderink (2017). We thank the 24 student participants for their help in identifying program strengths and weaknesses, and Jan Neth for organizational support. SUU staff Kate Crowe, Emma Hahn, Blaine Edwards, Jason Ramirez, and Curt Hill deserve our thanks for their assistance with off campus student dynamics. Finally, we thank Deanna Moore and Lance Syrett from Ruby’s Inn Resort, BCNP employees, Linda Mazzu and Kathleen Gonder, and Gale Pollock and Larry Davis from the Bryce Canyon Natural History Association for helping SUU get the SIP program up and running. This is paper UOTP0001 in the University of the Parks series from Southern Utah University.

References

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2011). The LEAP Vision for Learning: Outcomes, Practices, Impact, and Employers’ Views. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Brownell, J.E., L.E. Swaner. (2009). High-Impact Practices: Applying the learning outcomes literature to the development of successful campus programs. Peer Review, 11, 26-30.

Kilgo, C.A., Ezell Sheets, J.K., Pascarella, E.T. (2015). The link between high-impact practices and student learning: some longitudinal evidence. Higher Education, 69, 509-525.

Kuh, G.D., Kinzie J., Schuh, J.H., Whitt, E.J. (2005). Assessing conditions to enhance educational effectiveness: The inventory for student engagement and success. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kuh, G.D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

National Geographic. (2010). Top Ten Issues Facing National Parks. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/top-10/national-parks-issues/.

University of Colorado Denver. (n.d.) High-Impact Practices Operational Definitions. Retrieved from http://www.ucdenver.edu/student-services/resources/ue/HIP/Pages/form.aspx.

Wiggins, G.P., McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design. Danvers, MA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.