18 School Governance and Finance

4

School Governance and Finance

As a student, you may have enjoyed going to school with friends who lived in your neighborhood. But did you know that where you live also can impact how well-funded and well-resourced your school is? Because schools get much of their funding from property taxes, areas with more expensive houses have higher taxes, resulting in more school funding. While the United States believes education should be accessible to all, where you live can determine which resources will or will not be available to benefit your learning.

Governing and financing of schools varies at the federal, state, and local levels. This chapter provides an overview of structures for school governance and finance.

Chapter Outline

Governing Structures in Schools

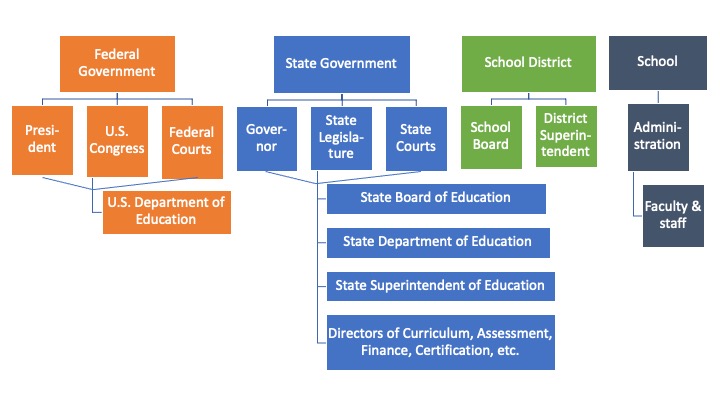

When considering how decisions concerning schools are made, there are various levels of involvement in educational governance at the federal, state and local levels. The federal government has limited powers, but maintains influence through promoting educational policies and reforms. The state government determines standards and policies for the state. The school district, sometimes called the local educational agency, is responsible for reporting and working with the state educational agency. At the local level, schools are combined by geographical lines to make up school districts. Finally, schools themselves follow a local governing structure. Figure 4.1 shows how schools are governed at the federal, state, district, and school level. The following section will discuss the structure and models at each level.

Figure 4.1: School Governance at Federal, State, District, and School Levels (adapted from Powell, 2019)

Federal

The United States federal government does not have direct authority over schools in each state. It does not tell schools what to teach or how. However, it does have the power to lead by:

- promoting policies and reform efforts;

- providing federal assistance appropriated by Congress;

- enforcing civil rights laws pertaining to education; and

- collecting and providing statistics on education (U.S. Department of Education, 2010).

President Andrew Jackson created a cabinet-level Department of Education in 1867, and Congress officially established the United States Department of Education in 1979. The department maintains its power through the distribution of federal education assistance. The head of the U.S. Department of Education is nominated by the president and approved by the Senate (U.S. Department of Education, 2010).

Many educational reforms have been promoted over the years. Table 4.2 outlines major educational acts and their impact on the U.S. education system. An act is an individual, stand-alone law. Major components of these acts and policies were designed to increase student achievement, which is measured through standardized testing. These acts also work to promote desegregation, protect against discrimination, and provide funding for underresourced students.

Table 4.2: Major Federal Acts in Education

| Year | Title/Act | Outcome |

| 1958 | National Defense Education Act (NDEA) | Provided federal school funding tied to testing and assessment requirements. |

| 1964 | Title VI of the Civil Rights Act | Prohibits discrimination “on the basis of race, color, and national origin in programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance.” |

| 1965 | Title 1 of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) | Created federal funding to support local schools in funding children in disadvantaged localities. |

| 1973 | Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act | Prohibited discrimination based on disability. |

| 1975 | Education for all Handicapped Children Act | Required public schools to provide free, appropriate education to students with disabilities. |

| 2002 | No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001 | Reauthorized ESEA (1965), but increased student testing, resources for recruiting teachers, and implementing research-based education programs. |

| 2009 | American Reinvestment and Recovery Act; included Race to the Top Initiative (U.S. Department of Education, 2009) | Earmarked $90 billion for education; designed to spur educational reform through $4.35 billion in competitive grant funds. This act also became the catalyst for the adoption of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). |

| 2015 | Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) reauthorized (ESSA, NCLB, and ESEA all refer to the same law, but differed in authorizations) (U.S. Department of Education, 2019) | Protections for disadvantaged and high-need students (English Language Learners) put in place. Requires states submit plans for academic standards, annual testing, and school report cards. |

It is important to note that all of these acts include federal funding formulas and methods of distributing federal funds. The progression of reform progressively ties funding to standardized assessment and curriculum, while also providing earmarked funds for Title 1 schools, which will be discussed below.

State

At the state level, there are three major positions that make decisions related to education.

- The governor acts as the chief officer and oversees policy. The governor also has the ability to veto and approve legislation.

- The state board of education includes members that act as policy makers and liaisons for educators.

- The chief state school officer, also called the state superintendent, is responsible for administrative oversight of state education agencies. The chief state school officer may be a member of the state board of education, but is directly responsible for making sure policies and state laws are followed.

These positions are elected or appointed in four different governance models. In the first model, the electorate elects the governor, who then appoints the state board of education and the chief state school officer. In the second model, the electorate elects the governor, who appoints the state board of education, who then appoints the chief state school officer. In the third model, the electorate elects the governor and the chief state school officer, then the governor appoints the state board of education. In the fourth model, the electorate elects the governor and the state board of education, who then appoints the state chief state school officer. There are also states that use modified versions of these models. It is important to understand your own state’s structure to see where accountability and authority are positioned.

At the state level, there are many central decisions made for all of the local school districts. First, the state allocates funds to each school district. Later in this chapter, school funding will be discussed, but the state makes up a considerable portion of funds for students. The state also sets standards for assessment and curriculum. It is then up to each locality to decide how the curriculum is implemented. The state is also responsible for licensing public and private schools, charter schools, and teachers and public-school staff (Chen, 2018). In addition, states establish compulsory education laws, which dictate between which ages students must attend school, often from ages five or six through 17 or 18, reflecting the range of the K-12 spectrum.

Local

Most states give responsibility for the operations and accounting to local school systems. These local school systems are defined by school districts. School district boundaries are often determined by geographic lines that may be drawn by county or centers of population. The majority of school districts are then run by school boards. School board members are either appointed by the mayor or city council, or they are elected by the public. The school board then elects a superintendent to oversee the district. The local school district makes decisions on allocation of funding within the district, curriculum, school policies, and employment policies and decisions.

The most local governance structure occurs in individual schools. Each school has its own leadership structure, usually headed by the principal (Chen, 2018). Other members of the school administration include assistant principals, with the number of assistant principals corresponding to the size of the student body. Administrators of individual schools are responsible for supporting their faculty and staff to fulfill district and state educational policies. Administrators are also liaisons between schools, families, and local communities.

Financing of Schools

School funding follows a similar pattern as school governance. The federal government distributes monies to State Education Agencies (SEAs), who then distribute monies to Local Education Agencies (LEAs). The following section will discuss how these funds are distributed and equality issues that arise.

Federal Funding

The federal government is responsible for providing around nine percent of a school’s budget. While this may not seem like very much, in 2013, that amounted to $71 billion dollars in federal funding (Census Bureau, 2015). The amount of federal funding for schools depends on the annual budget proposed by the president and set by Congress through a budget resolution. SEAs then submit plans to the federal government outlining how they will assess student progress and what their learning outcomes are.

In 1965, Congress passed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). In this act, Title I, Part A (Title I) provides federal assistance to LEAs and schools with large percentages of students from low-income, under-resourced families. These funds are to help ensure that all students are able to meet the state academic standards. Schools that receive these funds are often known as Title I schools or districts. The federal government provides funds to SEAs, who then allocate the money to LEAs. The LEAs are then responsible for allocating the funds to each school based on a funding formula. In general, these funds are used for targeted assistance programs, or if more than 40% of the students are eligible for Title I funds, then the funds may be used for school-wide improvement (EdBuild, 2020). The goal of distributing funds in this way is to make schools more equitable; however, these funds only account for nine percent of a school’s funding. The other 91 percent comes from state and local funding.

State and Local Funding

State and local school funding is based on complex funding formulas, with income often sourced from taxes on income, property, or sales. In general, most states use one or a combination of three different types of funding formulas: a student-based formula, a resource-based formula, or a hybrid formula. A student-based formula assumes a set amount that estimates how much it costs to educate one student. Adjustments are then made for students that are low income or receive special services for special education or English Language Learners. A resource-based formula uses the cost of resources or programs to fund specific programs. A hybrid funding formula will rely on multiple formulas. In 2020, 38 states used a student-based or hybrid funding formula. Across the nation, each state sets its own education budget, thus creating variance in funding and equitable education across states.

This funding disparity is further widened at the local level. Local funding makes up around 45 percent of a school’s budget. Once a state distributes funds to LEAs, the LEAs are then in charge of distributing funds to each school. In 47 states, funding for education is raised through property taxes (EdBuild, 2020). Thus, schools within wealthy districts will raise more funds than schools in economically disadvantaged areas. The federal funds distributed to low income areas through Title I do not make up for the inequities in funding.

Critical Lens: Inequitable Funding

Funding public schools based on local property taxes can perpetuate issues of inequity when it comes to accessing resources needed for high-quality education. This NPR article (Lombardo, 2019) explains how predominantly White school districts can receive up to $23 billion more than districts that serve predominantly students of color. Watch this video to learn more about how systemic racism impacts school funding.

School Choice

With so many school models available in the U.S., how do families choose which type of school their child should attend? School choice is a complex issue for families to navigate. What may be best for one student is not always best for another. The choices for students also vary by geographic and socioeconomic boundaries. Many families make school decisions based on the following factors:

- transportation and distance to chosen school;

- cost or tuition of school;

- curriculum and programs available;

- religious affiliation; and

- fit for the individual student.

Families in some areas of the U.S. also have greater access to the different models of schools presented at the beginning of this chapter than others. Small rural towns may only have one school within the immediate area. However, federal reform policies, such as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), have increased the number of charter schools and use of vouchers.

Conclusion

While many individuals and groups call for school reform in order to provide equity to all students, the process is complex. As you have seen in this chapter, federal oversight of schools is somewhat limited, allowing school governance to be different within each district and state. What may seem beneficial for students in one school or community may not be beneficial for students in another school or community; therefore, the federal government leaves many decisions about education to the discretion of state and local agencies. Many school, district, and state policies are also tied to federal, state, and local funding, which all use a variety of funding formulas. In order to create change, it is important that an individual understands how policy and funding decisions are developed and implemented.