8.2 Types of Nonverbal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Define kinesics.

- Define haptics.

- Define vocalics.

- Define proxemics.

- Define chronemics.

- Provide examples of types of nonverbal communication that fall under these categories.

Just as verbal language is broken up into various categories, there are also different types of nonverbal communication. As we learn about each type of nonverbal signal, keep in mind that nonverbals often work in concert with each other, combining to repeat, modify, or contradict the verbal message being sent.

Kinesics

The word kinesics comes from the root word kinesis, which means “movement,” and refers to the study of hand, arm, body, and face movements. Specifically, this section will outline the use of gestures, head movements and posture, eye contact, and facial expressions as nonverbal communication.

Gestures

There are three main types of gestures: adaptors, emblems, and illustrators (Andersen, 1999). Adaptors are touching behaviors and movements that indicate internal states typically related to arousal or anxiety. Adaptors can be targeted toward the self, objects, or others. In regular social situations, adaptors result from uneasiness, anxiety, or a general sense that we are not in control of our surroundings. Many of us subconsciously click pens, shake our legs, or engage in other adaptors during classes, meetings, or while waiting as a way to do something with our excess energy. Public speaking students who watch video recordings of their speeches notice nonverbal adaptors that they didn’t know they used. In public speaking situations, people most commonly use self- or object-focused adaptors. Common self-touching behaviors like scratching, twirling hair, or fidgeting with fingers or hands are considered self-adaptors. Use of object adaptors can also signal boredom as people play with the straw in their drink or peel the label off a bottle of beer. Smartphones have become common object adaptors, as people can fiddle with their phones to help ease anxiety.

Emblems are gestures that have a specific agreed-on meaning. These are still different from the signs used by hearing-impaired people or others who communicate using American Sign Language (ASL). Even though they have a generally agreed-on meaning, they are not part of a formal sign system like ASL that is explicitly taught to a group of people. A hitchhiker’s raised thumb, the “OK” sign with thumb and index finger connected in a circle with the other three fingers sticking up, and the raised middle finger are all examples of emblems that have an agreed-on meaning or meanings with a culture. Emblems can be still or in motion; for example, circling the index finger around at the side of your head says “He or she is crazy,” or rolling your hands over and over in front of you says “Move on.”

Illustrators are the most common type of gesture and are used to illustrate the verbal message they accompany. For example, you might use hand gestures to indicate the size or shape of an object. Unlike emblems, illustrators do not typically have meaning on their own and are used more subconsciously than emblems. These largely involuntary and seemingly natural gestures flow from us as we speak but vary in terms of intensity and frequency based on context. Although we are never explicitly taught how to use illustrative gestures, we do it automatically. Think about how you still gesture when having an animated conversation on the phone even though the other person can’t see you.

Head Movements and Posture

I group head movements and posture together because they are often both used to acknowledge others and communicate interest or attentiveness. In terms of head movements, a head nod is a universal sign of acknowledgement in cultures where the formal bow is no longer used as a greeting. An innate and universal head movement is the headshake back and forth to signal “no.” This nonverbal signal begins at birth, even before a baby has the ability to know that it has a corresponding meaning. Babies shake their head from side to side to reject their mother’s breast and later shake their head to reject attempts to spoon-feed (Pease & Pease, 2004). This biologically based movement then sticks with us to be a recognizable signal for “no.”

There are four general human postures: standing, sitting, squatting, and lying down (Hargie, 2011). Within each of these postures there are many variations, and when combined with particular gestures or other nonverbal cues they can express many different meanings. Most of our communication occurs while we are standing or sitting. One interesting standing posture involves putting our hands on our hips and is a nonverbal cue that we use subconsciously to make us look bigger and show assertiveness. When the elbows are pointed out, this prevents others from getting past us as easily and is a sign of attempted dominance or a gesture that says we’re ready for action. In terms of sitting, leaning back shows informality and indifference, straddling a chair is a sign of dominance (but also some insecurity because the person is protecting the vulnerable front part of his or her body), and leaning forward shows interest and attentiveness (Pease & Pease, 2004).

Eye Contact

We also communicate through eye behaviors, primarily eye contact. While eye behaviors are often studied under the category of kinesics, they have their own branch of nonverbal studies called oculesics, which comes from the Latin word oculus, meaning “eye.” The face and eyes are the main point of focus during communication, and along with our ears our eyes take in most of the communicative information around us. The saying “The eyes are the window to the soul” is actually accurate in terms of where people typically think others are “located,” which is right behind the eyes (Andersen, 1999).

Eye contact serves several communicative functions ranging from regulating interaction to monitoring interaction, to conveying information, to establishing interpersonal connections. In terms of regulating communication, we use eye contact to signal to others that we are ready to speak or we use it to cue others to speak. I’m sure we’ve all been in that awkward situation where a teacher asks a question, no one else offers a response, and he or she looks directly at us as if to say, “What do you think?” In that case, the teacher’s eye contact is used to cue us to respond. During an interaction, eye contact also changes as we shift from speaker to listener.

Aside from regulating conversations, eye contact is also used to monitor interaction by taking in feedback and other nonverbal cues and to send information. Our eyes bring in the visual information we need to interpret people’s movements, gestures, and eye contact. A speaker can use his or her eye contact to determine if an audience is engaged, confused, or bored and then adapt his or her message accordingly. Our eyes also send information to others. People know not to interrupt when we are in deep thought because we naturally look away from others when we are processing information. Making eye contact with others also communicates that we are paying attention and are interested in what another person is saying. As we will learn in Chapter 9: “Listening”, eye contact is a key part of active listening.

Eye contact can also be used to intimidate others. We have social norms about how much eye contact we make with people, and those norms vary depending on the setting and the person. Staring at another person in some contexts could communicate intimidation, while in other contexts it could communicate flirtation. As we learned, eye contact is a key immediacy behavior, and it signals to others that we are available for communication. Once communication begins, if it does, eye contact helps establish rapport or connection. We can also use our eye contact to signal that we do not want to make a connection with others. For example, in a public setting like an airport or a gym where people often make small talk, we can avoid making eye contact with others to indicate that we do not want to engage in small talk with strangers.

Eye contact sends and receives important communicative messages that help us interpret others’ behaviors, convey information about our thoughts and feelings, and facilitate or impede rapport or connection. This list reviews the specific functions of eye contact:

- Regulate interaction and provide turn-taking signals

- Monitor communication by receiving nonverbal communication from others

- Signal cognitive activity (we look away when processing information)

- Express engagement (we show people we are listening with our eyes)

- Convey intimidation

- Express flirtation

- Establish rapport or connection

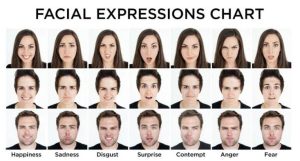

Facial Expressions

Our faces are the most expressive part of our bodies. Think of how photos are often intended to capture a particular expression “in a flash” to preserve for later viewing. Even though a photo is a snapshot in time, we can still interpret much meaning from a human face caught in a moment of expression, and basic facial expressions are recognizable by humans all over the world. Much research has supported the universality of a core group of facial expressions: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust. The first four are especially identifiable across cultures (Andersen, 1999). However, the triggers for these expressions and the cultural and social norms that influence their displays are still culturally diverse. If you’ve spent much time with babies you know that they’re capable of expressing all these emotions. Getting to see the pure and innate expressions of joy and surprise on a baby’s face is what makes playing peek-a-boo so entertaining for adults. As we get older, we learn and begin to follow display rules for facial expressions and other signals of emotion and also learn to better control our emotional expression based on the norms of our culture.

Haptics

Think of how touch has the power to comfort someone in moment of sorrow when words alone cannot. This positive power of touch is countered by the potential for touch to be threatening because of its connection to sex and violence. To learn about the power of touch, we turn to haptics, which refers to the study of communication by touch. A lack of nonverbal communication competence related to touch could have negative interpersonal consequences; for example, if we don’t follow the advice we’ve been given about the importance of a firm handshake, a person might make negative judgments about our confidence or credibility. A lack of competence could have more dire negative consequences, including legal punishment, if we touch someone inappropriately (intentionally or unintentionally). Touch is necessary for human social development, and it can be welcoming, threatening, or persuasive. Research projects have found that female restaurant servers received larger tips when they touched patrons, and that people were more likely to sign a petition when the petitioner touched them during their interaction (Andersen, 1999).

Touch is also used in many other contexts—for example, during play (e.g., arm wrestling), during physical conflict (e.g., slapping), and during conversations (e.g., to get someone’s attention) (Jones, 1999). We also inadvertently send messages through accidental touch (e.g., bumping into someone). One of my interpersonal communication professors admitted that she enjoyed going to restaurants to observe “first-date behavior” and boasted that she could predict whether or not there was going to be a second date based on the couple’s nonverbal communication. What sort of touching behaviors would indicate a good or bad first date?

During a first date or less formal initial interactions, quick fleeting touches give an indication of interest. For example, a pat on the back is an abbreviated hug (Andersen, 1999). In general, the presence or absence of touching cues us into people’s emotions. So as the daters sit across from each other, one person may lightly tap the other’s arm after he or she said something funny. If the daters are sitting side by side, one person may cross his or her legs and lean toward the other person so that each person’s knees or feet occasionally touch. Touching behavior as a way to express feelings is often reciprocal. A light touch from one dater will be followed by a light touch from the other to indicate that the first touch was OK. While verbal communication could also be used to indicate romantic interest, many people feel too vulnerable at this early stage in a relationship to put something out there in words. If your date advances a touch and you are not interested, it is also unlikely that you will come right out and say, “Sorry, but I’m not really interested.” Instead, due to common politeness rituals, you would be more likely to respond with other forms of nonverbal communication like scooting back, crossing your arms, or simply not acknowledging the touch.

Vocalics

We learned earlier that paralanguage refers to the vocalized but nonverbal parts of a message. Vocalics is the study of paralanguage, which includes the vocal qualities that go along with verbal messages, such as pitch, volume, rate, vocal quality, and verbal fillers (Andersen, 1999).

Pitch helps convey meaning, regulate conversational flow, and communicate the intensity of a message. Even babies recognize a sentence with a higher pitched ending as a question. Of course, no one ever tells us these things explicitly; we learn them through observation and practice. We do not pick up on some more subtle and/or complex patterns of paralanguage involving pitch until we are older. Children, for example, have a difficult time perceiving sarcasm, which is usually conveyed through paralinguistic characteristics like pitch and tone rather than the actual words being spoken (Andersen, 1999).

Paralanguage provides important context for the verbal content of speech. For example, volume helps communicate intensity. A louder voice is usually thought of as more intense, although a soft voice combined with a certain tone and facial expression can be just as intense. We typically adjust our volume based on our setting, the distance between people, and the relationship. In our age of computer-mediated communication, TYPING IN ALL CAPS is usually seen as offensive, as it is equated with yelling.

Speaking rate refers to how fast or slow a person speaks can lead others to form impressions about our emotional state, credibility, and intelligence. As with volume, variations in speaking rate can interfere with the ability of others to receive and understand verbal messages. A slow speaker could bore others and lead their attention to wander. A fast speaker may be difficult to follow, and the fast delivery can actually distract from the message. Speaking a little faster than the normal 120–150 words a minute, however, can be beneficial, as people tend to find speakers whose rate is above average more credible and intelligent (Buller & Burgoon, 1986). When speaking at a faster-than-normal rate, it is important that a speaker also clearly articulate and pronounce his or her words.

Our tone of voice can be controlled somewhat with pitch, volume, and emphasis, but each voice has a distinct quality known as a vocal signature. Voices vary in terms of resonance, pitch, and tone, and some voices are more pleasing than others. People typically find pleasing voices that employ vocal variety and are not monotone, are lower pitched (particularly for males), and do not exhibit particular regional accents. Many people perceive nasal voices negatively and assign negative personality characteristics to them (Andersen, 1999).

Verbal fillers are sounds that fill gaps in our speech as we think about what to say next. They are considered a part of nonverbal communication because they are not like typical words that stand in for a specific meaning or meanings. Verbal fillers such as “um,” “uh,” “like,” and “ah” are common in regular conversation and are not typically disruptive. As we learned earlier, the use of verbal fillers can help a person “keep the floor” during a conversation if they need to pause for a moment to think before continuing on with verbal communication. Verbal fillers in more formal settings, like a public speech, can hurt a speaker’s credibility.

The following is a review of the various communicative functions of vocalics:

- Repetition. Vocalic cues reinforce other verbal and nonverbal cues (e.g., saying “I’m not sure” with an uncertain tone).

- Complementing. Vocalic cues elaborate on or modify verbal and nonverbal meaning (e.g., the pitch and volume used to say “I love sweet potatoes” would add context to the meaning of the sentence, such as the degree to which the person loves sweet potatoes or the use of sarcasm).

- Accenting. Vocalic cues allow us to emphasize particular parts of a message, which helps determine meaning (e.g., “She is my friend,” or “She is my friend,” or “She is my friend”).

- Substituting. Vocalic cues can take the place of other verbal or nonverbal cues (e.g., saying “uh huh” instead of “I am listening and understand what you’re saying”).

- Regulating. Vocalic cues help regulate the flow of conversations (e.g., falling pitch and slowing rate of speaking usually indicate the end of a speaking turn).

- Contradicting. Vocalic cues may contradict other verbal or nonverbal signals (e.g., a person could say “I’m fine” in a quick, short tone that indicates otherwise).

Proxemics

Proxemics refers to the study of how space and distance influence communication. We only need look at the ways in which space shows up in common metaphors to see that space, communication, and relationships are closely related. For example, when we are content with and attracted to someone, we say we are “close” to him or her. When we lose connection with someone, we may say he or she is “distant.” In general, space influences how people communicate and behave. Smaller spaces with a higher density of people often lead to breaches of our personal space bubbles. If this is a setting in which this type of density is expected beforehand, like at a crowded concert or on a train during rush hour, then we make various communicative adjustments to manage the space issue. Unexpected breaches of personal space can lead to negative reactions, especially if we feel someone has violated our space voluntarily, meaning that a crowding situation didn’t force them into our space. To better understand how proxemics functions in nonverbal communication, we will more closely examine the proxemic distances associated with personal space and the concept of territoriality.

proxemic Distances

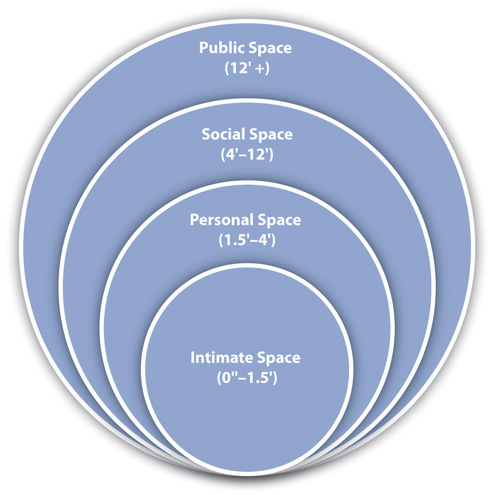

We all have varying definitions of what our “personal space” is, and these definitions are contextual and depend on the situation and the relationship. Although our bubbles are invisible, people are socialized into the norms of personal space within their cultural group. Scholars have identified four zones for US Americans, which are public, social, personal, and intimate distance (Hall, 1968). You can see how these zones relate to each other and to the individual in Figure 8.2.1 “Proxemic Zones of Personal Space”. Even within a particular zone, interactions may differ depending on whether someone is in the outer or inner part of the zone.

Figure 8.2.1 Proxemic Zones of Personal Space

public Space (12 Feet or More)

Public and social zones refer to the space four or more feet away from our body, and the communication that typically occurs in these zones is formal and not intimate. Public space starts about twelve feet from a person and extends out from there. This would typically be used when a person is engaging in a formal speech and is removed from the audience to allow the audience to see or when a high-profile or powerful person like a celebrity or executive maintains such a distance as a sign of power or for safety and security reasons. In terms of regular interaction, we are often not obligated or expected to acknowledge or interact with people who enter our public zone. It would be difficult to have a deep conversation with someone at this level because you have to speak louder and don’t have the physical closeness that is often needed to promote emotional closeness and/or establish rapport.

Social Space (4-12 Feet)

Communication that occurs in the social zone, which is four to twelve feet away from our body, is typically in the context of a professional or casual interaction, but not intimate or public. This distance is preferred in many professional settings because it reduces the suspicion of any impropriety. It is also possible to have people in the outer portion of our social zone but not feel obligated to interact with them, but when people come much closer than six feet to us then we often feel obligated to at least acknowledge their presence. In many typically sized classrooms, much of your audience for a speech will actually be in your social zone rather than your public zone, which is actually beneficial because it helps you establish a better connection with them.

Personal Space (1.5-4 Feet)

Personal and intimate zones refer to the space that starts at our physical body and extends four feet. These zones are reserved for friends, close acquaintances, and significant others. Much of our communication occurs in the personal zone, which is what we typically think of as our “personal space bubble” and extends from 1.5 feet to 4 feet away from our body. Even though we are getting closer to the physical body of another person, we may use verbal communication at this point to signal that our presence in this zone is friendly and not intimate.

Intimate Space

As we breach the invisible line that is 1.5 feet from our body, we enter the intimate zone, which is reserved for only the closest friends, family, and romantic/intimate partners. It is impossible to completely ignore people when they are in this space, even if we are trying to pretend that we’re ignoring them. A breach of this space can be comforting in some contexts and annoying or frightening in others. We need regular human contact that isn’t just verbal but also physical. There are also social norms regarding the amount of this type of closeness that can be displayed in public, as some people get uncomfortable even seeing others interacting in the intimate zone. While some people are comfortable engaging in or watching others engage in PDAs (public displays of affection) others are not.

So what happens when our space is violated? Although these zones are well established in research for personal space preferences of US Americans, individuals vary in terms of their reactions to people entering certain zones, and determining what constitutes a “violation” of space is subjective and contextual. We’ve all had to get into a crowded elevator or wait in a long line. In such situations, we may rely on some verbal communication to reduce immediacy and indicate that we are not interested in closeness and are aware that a breach has occurred. Interestingly, as we will learn in our discussion of territoriality, we do not often use verbal communication to defend our personal space during regular interactions. Instead, we rely on more nonverbal communication like moving, crossing our arms, or avoiding eye contact to deal with breaches of space.

Territoriality

Territoriality is an innate drive to take up and defend spaces. This drive is shared by many creatures and entities, ranging from packs of animals to individual humans to nations. Whether it’s a gang territory, your preferred place to sit in a restaurant, or your usual desk in the classroom, we claim certain spaces as our own. There are three main divisions for territory: primary, secondary, and public (Hargie, 2011). Sometimes our claim to a space is official. These spaces are known as our primary territories because they are marked or understood to be exclusively ours and under our control. A person’s house, yard, room, desk, side of the bed, or shelf in the medicine cabinet could be considered primary territories.

Secondary territories don’t belong to us and aren’t exclusively under our control, but they are associated with us, which may lead us to assume that the space will be open and available to us when we need it without us taking any further steps to reserve it. This happens in classrooms regularly. Students often sit in the same desk or at least same general area as they did on the first day of class. There may be some small adjustments during the first couple of weeks, but by a month into the semester, I don’t notice students moving much voluntarily. When someone else takes a student’s regular desk, she or he is typically annoyed.

Public territories are open to all people. People are allowed to mark public territory and use it for a limited period of time, but space is often up for grabs, which makes public space difficult to manage for some people and can lead to conflict. To avoid this type of situation, people use a variety of objects that are typically recognized by others as nonverbal cues that mark a place as temporarily reserved—for example, jackets, bags, papers, or a drink.

Chronemics

Chronemics refers to the study of how time affects communication. Time can be classified into several different categories, including biological, personal, physical, and cultural time (Andersen, 1999). Biological time refers to the rhythms of living things. Humans follow a circadian rhythm, meaning that we are on a daily cycle that influences when we eat, sleep, and wake. When our natural rhythms are disturbed, by all-nighters, jet lag, or other scheduling abnormalities, our physical and mental health and our communication competence and personal relationships can suffer.

Personal time refers to the ways in which individuals experience time. The way we experience time varies based on our mood, our interest level, and other factors. Think about how quickly time passes when you are interested in and therefore engaged in something. I have taught fifty-minute classes that seemed to drag on forever and three-hour classes that zipped by. Individuals also vary based on whether or not they are future or past oriented. People with past-time orientations may want to reminisce about the past, reunite with old friends, and put considerable time into preserving memories and keepsakes in scrapbooks and photo albums. People with future-time orientations may spend the same amount of time making career and personal plans, writing out to-do lists, or researching future vacations, potential retirement spots, or what book they’re going to read next.

Physical time refers to the fixed cycles of days, years, and seasons. Physical time, especially seasons, can affect our mood and psychological states. Some people experience seasonal affective disorder that leads them to experience emotional distress and anxiety during the changes of seasons, primarily from warm and bright to dark and cold (summer to fall and winter).

Cultural time refers to how a large group of people view time. Polychronic people do not view time as a linear progression that needs to be divided into small units and scheduled in advance. Polychronic people keep more flexible schedules and may engage in several activities at once. Monochronic people tend to schedule their time more rigidly and do one thing at a time. A polychronic or monochronic orientation to time influences our social realities and how we interact with others.

Additionally, the way we use time depends in some ways on our status. For example, doctors can make their patients wait for extended periods of time, and executives and celebrities may run consistently behind schedule, making others wait for them. Promptness and the amount of time that is socially acceptable for lateness and waiting varies among individuals and contexts.

Key Takeaways

-

Kinesics refers to body movements and posture and includes the following components:

- Gestures are arm and hand movements and include adaptors like clicking a pen or scratching your face, emblems like a thumbs-up to say “OK,” and illustrators like bouncing your hand along with the rhythm of your speaking.

- Head movements and posture include the orientation of movements of our head and the orientation and positioning of our body and the various meanings they send. Head movements such as nodding can indicate agreement, disagreement, and interest, among other things. Posture can indicate assertiveness, defensiveness, interest, readiness, or intimidation, among other things.

- Eye contact is studied under the category of oculesics and specifically refers to eye contact with another person’s face, head, and eyes and the patterns of looking away and back at the other person during interaction. Eye contact provides turn-taking signals, signals when we are engaged in cognitive activity, and helps establish rapport and connection, among other things.

- Facial expressions refer to the use of the forehead, brow, and facial muscles around the nose and mouth to convey meaning. Facial expressions can convey happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and other emotions.

- Haptics refers to touch behaviors that convey meaning during interactions. Touch operates at many levels, including functional-professional, social-polite, friendship-warmth, and love-intimacy.

- Vocalics refers to the vocalized but not verbal aspects of nonverbal communication, including our speaking rate, pitch, volume, tone of voice, and vocal quality. These qualities, also known as paralanguage, reinforce the meaning of verbal communication, allow us to emphasize particular parts of a message, or can contradict verbal messages.

- Proxemics refers to the use of space and distance within communication. US Americans, in general, have four zones that constitute our personal space: the public zone (12 or more feet from our body), social zone (4–12 feet from our body), the personal zone (1.5–4 feet from our body), and the intimate zone (from body contact to 1.5 feet away). Proxemics also studies territoriality, or how people take up and defend personal space.

- Chronemics refers the study of how time affects communication and includes how different time cycles affect our communication, including the differences between people who are past or future oriented and cultural perspectives on time as fixed and measured (monochronic) or fluid and adaptable (polychronic).

- Personal presentation and environment refers to how the objects we adorn ourselves and our surroundings with, referred to as artifacts, provide nonverbal cues that others make meaning from and how our physical environment—for example, the layout of a room and seating positions and arrangements—influences communication.

Exercises

- Provide some examples of how eye contact plays a role in your communication throughout the day.

- One of the key functions of vocalics is to add emphasis to our verbal messages to influence the meaning. Provide a meaning for each of the following statements based on which word is emphasized: “She is my friend.” “She is my friend.” “She is my friend.”

- Getting integrated: Many people do not think of time as an important part of our nonverbal communication. Provide an example of how chronemics sends nonverbal messages in academic settings, professional settings, and personal settings.

References

Allmendinger, K., “Social Presence in Synchronous Virtual Learning Situations: The Role of Nonverbal Signals Displayed by Avatars,” Educational Psychology Review 22, no. 1 (2010): 42.

Andersen, P. A., Nonverbal Communication: Forms and Functions (Mountain View, CA: Mayfield, 1999), 36.

Baylor, A. L., “The Design of Motivational Agents and Avatars,” Educational Technology Research and Development 59, no. 2 (2011): 291–300.

Buller, D. B. and Judee K. Burgoon, “The Effects of Vocalics and Nonverbal Sensitivity on Compliance,” Human Communication Research 13, no. 1 (1986): 126–44.

Evans, D., Emotion: The Science of Sentiment (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 107.

Floyd, K., Communicating Affection: Interpersonal Behavior and Social Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 33–34.

Fox, J. and Jeremy M. Bailenson, “Virtual Self-Modeling: The Effects of Vicarious Reinforcement and Identification on Exercise Behaviors,” Media Psychology 12, no. 1 (2009): 1–25.

Guerrero, L. K. and Kory Floyd, Nonverbal Communication in Close Relationships (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2006): 176.

Hall, E. T., “Proxemics,” Current Anthropology 9, no. 2 (1968): 83–95.

Hargie, O., Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice, 5th ed. (London: Routledge, 2011), 63.

Heslin, R. and Tari Apler, “Touch: A Bonding Gesture,” in Nonverbal Interaction, eds. John M. Weimann and Randall Harrison (Longon: Sage, 1983), 47–76.

Jones, S. E., “Communicating with Touch,” in The Nonverbal Communication Reader: Classic and Contemporary Readings, 2nd ed., eds. Laura K. Guerrero, Joseph A. Devito, and Michael L. Hecht (Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 1999).

Kim, C., Sang-Gun Lee, and Minchoel Kang, “I Became an Attractive Person in the Virtual World: Users’ Identification with Virtual Communities and Avatars,” Computers in Human Behavior, 28, no. 5 (2012): 1663–69

Kravitz, D., “Airport ‘Pat-Downs’ Cause Growing Passenger Backlash,” The Washington Post, November 13, 2010, accessed June 23, 2012, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/11/12/AR2010111206580.html?sid=ST2010113005385.

Martin, J. N. and Thomas K. Nakayama, Intercultural Communication in Contexts, 5th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 276.

McKay, M., Martha Davis, and Patrick Fanning, Messages: Communication Skills Book, 2nd ed. (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 1995), 59.

Pease, A. and Barbara Pease, The Definitive Book of Body Language (New York, NY: Bantam, 2004), 121.

Strunksy, S., “New Airport Service Rep Is Stiff and Phony, but She’s Friendly,” NJ.COM, May 22, 2012, accessed June 28, 2012, http://www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/2012/05/new_airport_service_rep_is_sti.html.

Tecca, “New York City Airports Install New, Expensive Holograms to Help You Find Your Way,” Y! Tech: A Yahoo! News Blog, May 22, 2012, accessed June 28, 2012, http://news.yahoo.com/blogs/technology-blog/york-city-airports-install-expensive-holograms-help-way-024937526.html.

Thomas, A. R., Soft Landing: Airline Industry Strategy, Service, and Safety (New York, NY: Apress, 2011), 117–23.

The study of hand, arm, body and face movements

Touching behaviors and movements that indicate internal states typically related to arousal or anxiety; for example, clicking pens, shaking legs, etc.

Gestures that have a specific agreed upon meaning; for example, a hitchhiker’s raised thumb which in the US would mean, “I need a ride.”

Gestures used to illustrate the verbal message they accompany; for example, using hand gestures to indicate the size or shape of an object

The study of eye behaviors on communication, especially eye contact; sometimes considered a subset of kinesics

The study of communication by touch

The study of paralangage, which includes vocal qualities such as pitch, volume, rate, vocal quality, and verbal fillers

A tonal quality that helps convey meaning, regulate conversational flow, and communicate the intensity of a message

Sounds that fill gaps speech between words

A function of vocalics in that vocalic cues reinforce other verbal and nonverbal cues; for example, saying “I’m not sure” with an uncertain tone

A function of vocalics in that vocalic cues elaborate on or modify verbal and nonverbal meaning; for example, using pitch and volume to say “I love pickles” would add context to the meaning of the sentence, such as the degree to which the person loves pickles or the use of sarcasm

A function of vocalics in that vocalic cues allow us to emphasize particular parts of a message, which helps determine meaning; for example, “She is my friend” or “She is my friend”

A function of vocalics in that vocalic cues can take the place of other verbal of nonverbal cues; for example, saying “uh huh” instead of “I am listening and understand what you’re saying.”

A function of vocalics in that vocalic cues help regulate the flow of conversations; for example, falling pitch and slowing rate of speaking usually indicate the end of a speaking turn

A function of vocalics in that vocalic cues may contradict other verbal or nonverbal signals; for example, a person could say, “I’m fine” in a quick short tone that indicates otherwise

The study of how space and distance influence communication

An innate drive to take up and defend spaces

The study of how time affects communication; includes how different time cycles affects communication and the differences between people who are past or future oriented, etc.

Cultures where people do not view time as a linear progression and tend to be more flexible with expected scheduling

Cultures where people tend to schedule their time rigidly and value punctuality