5.1 Leadership and Small Group Communication

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast various leadership styles.

- Discuss the types of power that a leader may tap into.

Leadership is one of the most studied aspects of group communication. Scholars in business, communication, psychology, and many other fields have written extensively about the qualities of leaders, theories of leadership, and how to build leadership skills. It’s important to point out that although a group may have only one official leader, other group members play important leadership roles. Making this distinction also helps us differentiate between leaders and leadership (Hargie, 2011). The leader is a group role that is associated with a high-status position and may be formally or informally recognized by group members. Leadership is a complex of beliefs, communication patterns, and behaviors that influence the functioning of a group and move a group toward the completion of its task. A person in the role of leader may provide no or poor leadership. Likewise, a person who is not recognized as a “leader” in title can provide excellent leadership. In the remainder of this section, we will discuss some approaches to the study of leadership, leadership styles, and leadership and group dynamics.

Leadership Styles

Given the large amount of research done on leadership, it is not surprising that there are several different ways to define or categorize leadership styles. In general, effective leaders do not fit solely into one style in any of the following classifications. Instead, they are able to adapt their leadership style to fit the relational and situational context (Wood, 1977). Among the many leadership style approaches found in scholarly and trade publications, this text focuses on four leadership styles, as identified in Path-Goal Theory: directive, participative, supportive, and achievement oriented (House & Mitchell, 1974, 1996).

Directive Leaders

Directive leaders help provide psychological structure for their group members by clearly communicating expectations, keeping a schedule and agenda, providing specific guidance as group members work toward the completion of their task, and taking the lead on setting and communicating group rules and procedures. Although this is most similar to the autocratic leadership style mentioned before, it is more nuanced and flexible. The originators of this model note that a leader can be directive without being seen as authoritarian. To do this, directive leaders must be good motivators who encourage productivity through positive reinforcement or reward rather than through the threat of punishment.

A directive leadership style is effective in groups that do not have a history and may require direction to get started on their task. It can also be the most appropriate method during crisis situations in which decisions must be made under time constraints or other extraordinary pressures. When groups have an established history and are composed of people with unique skills and expertise, a directive approach may be seen as “micromanaging.” In these groups, a more participative style may be the best option.

Participative Leaders

Participative leaders work to include group members in the decision-making process by soliciting and considering their opinions and suggestions. When group members feel included, their personal goals are more likely to align with the group and organization’s goals, which can help productivity. This style of leadership can also aid in group member socialization, as the members feel like they get to help establish group norms and rules, which affects cohesion and climate. When group members participate more, they buy into the group’s norms and goals more, which can increase conformity pressures for incoming group members. As we learned earlier, this is good to a point, but it can become negative when the pressures lead to unethical group member behavior. In addition to consulting group members for help with decision making, participative leaders also grant group members more freedom to work independently. This can lead group members to feel trusted and respected for their skills, which can increase their effort and output.

The participative method of leadership is similar to the democratic style discussed earlier, and it is a style of leadership practiced in many organizations that have established work groups that meet consistently over long periods of time. US companies began to adopt a more participative and less directive style of management in the 1980s after organizational scholars researched teamwork and efficiency in Japanese corporations. Japanese managers included employees in decision making, which blurred the line between the leader and other group members and enhanced productivity. These small groups were called quality circles, because they focused on group interaction intended to improve quality and productivity (Cragan & Wright, 1991).

Supportive Leaders

Supportive leaders show concern for their followers’ needs and emotions. They want to support group members’ welfare through a positive and friendly group climate. These leaders are good at reducing the stress and frustration of the group, which helps create a positive climate and can help increase group members’ positive feelings about the task and other group members. As we will learn later, some group roles function to maintain the relational climate of the group, and several group members often perform these role behaviors. With a supportive leader as a model, such behaviors would likely be performed as part of established group norms, which can do much to enhance social cohesion. Supportive leaders do not provide unconditionally positive praise. They also competently provide constructive criticism in order to challenge and enhance group members’ contributions.

A supportive leadership style is more likely in groups that are primarily relational rather than task focused. For example, support groups and therapy groups benefit from a supportive leader. While maintaining positive relationships is an important part of any group’s functioning, most task-oriented groups need to spend more time on task than social functions in order to efficiently work toward the completion of their task. Skilled directive or participative leaders of task-oriented groups would be wise to employ supportive leadership behaviors when group members experience emotional stress to prevent relational stress from negatively impacting the group’s climate and cohesion.

Achievement-Oriented Leaders

Achievement-oriented leaders strive for excellence and set challenging goals, constantly seeking improvement and exhibiting confidence that group members can meet their high expectations. These leaders often engage in systematic social comparison, keeping tabs on other similar high-performing groups to assess their expectations and the group’s progress. This type of leadership is similar to what other scholars call transformational or visionary leadership and is often associated with leaders like former Apple CEO Steve Jobs, talk show host and television network CEO Oprah Winfrey, former president Bill Clinton, and business magnate turned philanthropist Warren Buffett. Achievement-oriented leaders are likely less common than the other styles, as this style requires a high level of skill and commitment on the part of the leader and the group. Although rare, these leaders can be found at all levels of groups ranging from local school boards to Fortune 500 companies. Certain group dynamics must be in place in order to accommodate this leadership style. Groups for which an achievement-oriented leadership style would be effective are typically intentionally created and are made up of members who are skilled and competent in regards to the group’s task. In many cases, the leader is specifically chosen because of his or her reputation and expertise, and even though the group members may not have a history of working with the leader, the members and leader must have a high degree of mutual respect.

“Getting Plugged In”

Steve Jobs as an Achievement-Oriented Leader

“Where can you find a leader with Jobs’ willingness to fail, his sheer tenacity, persistence, and resiliency, his grandiose ego, his overwhelming belief in himself?” (Deutschman, 2012) This closing line of an article following the death of Steve Jobs clearly illustrates the larger-than-life personality and extraordinary drive of achievement-oriented leaders. Jobs, who founded Apple Computers, was widely recognized as a visionary with a brilliant mind during his early years at the helm of Apple (from 1976 to 1985), but he hadn’t yet gained respect as a business leader. Jobs left the company and later returned in 1997. After his return, Apple reached its height under his leadership, which was now enhanced by business knowledge and skills he gained during his time away from the company. The fact that Jobs was able to largely teach himself the ins and outs of business practices is a quality of achievement-oriented leaders, who are constantly self-reflective and evaluate their skills and performance, making adaptations as necessary.

Achievement-oriented leaders also often possess good instincts, allowing them to make decisions quickly while acknowledging the potential for failure but also showing a resiliency that allows them to bounce back from mistakes and come back stronger. Rather than bringing in panels of experts, presenting ideas to focus groups for feedback, or putting a new product through market research and testing, Jobs relied on his instincts, which led to some embarrassing failures and some remarkable successes that overshadowed the failures. Although Jobs made unilateral decisions, he relied heavily on the creative and technical expertise of others who worked for him and were able to make his creative, innovative, and some say genius ideas reality. As do other achievement-oriented leaders, Jobs held his group members to exceptionally high standards and fostered a culture that mirrored his own perfectionism. Constant comparisons to other technological innovators like Bill Gates, CEO of Microsoft, pushed Jobs and those who worked for him to work tirelessly to produce the “next big thing.” Achievement-oriented leaders like Jobs have been described as maniacal, intense, workaholics, perfectionists, risk takers, narcissists, innovative, and visionary. These descriptors carry positive and negative connotations but often yield amazing results when possessed by a leader, the likes of which only seldom come around.

- Do you think Jobs could have been as successful had he employed one of the other leadership styles? Why or why not? How might the achievement-oriented leadership style be well suited for a technology company like Apple or the technology field in general?

- In what circumstances would you like to work for an achievement-oriented leader, and why? In what circumstances would you prefer not to work with an achievement-oriented leader, and why?

- Do some research on another achievement-oriented leader. Discuss how that leader’s traits are similar to and/or different from those of Steve Jobs.

Leadership and Power

Leaders help move group members toward the completion of their goal using various motivational strategies. The types of power leaders draw on to motivate have long been a topic of small group study. A leader may possess or draw on any of the following five types of power to varying degrees: legitimate, expert, referent, information, and reward/coercive (French Jr. & Raven, 1959). Effective leaders do not need to possess all five types of power. Instead, competent leaders know how to draw on other group members who may be better able to exercise a type of power in a given situation.

Legitimate Power

The very title of leader brings with it legitimate power, which is power that flows from the officially recognized position, status, or title of a group member. For example, the leader of the “Social Media Relations Department” of a retail chain receives legitimate power through the title “director of social media relations.” It is important to note though that being designated as someone with status or a position of power doesn’t mean that the group members respect or recognize that power. Even with a title, leaders must still earn the ability to provide leadership. Of the five types of power, however, the leader alone is most likely to possess legitimate power.

Milgram’s Studies on Obedience to Authority

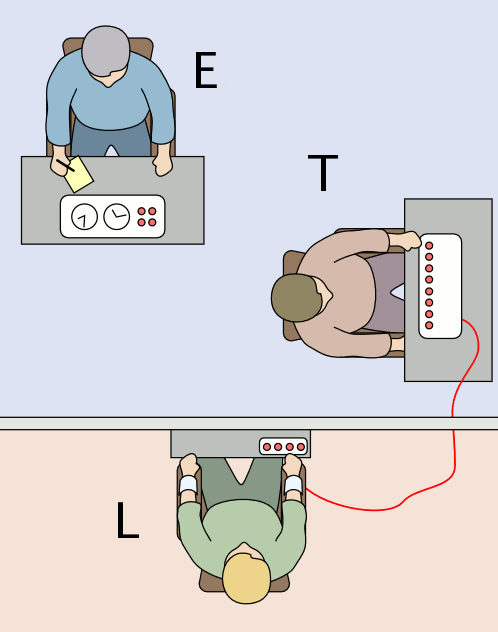

The powerful ability of those in authority to control others was demonstrated in a remarkable set of studies performed by Stanley Milgram (1963). Milgram was interested in understanding the factors that lead people to obey the orders given by people in authority. He designed a study in which he could observe the extent to which a person who presented himself as an authority would be able to produce obedience, even to the extent of leading people to cause harm to others.

Like his professor Solomon Asch, Milgram’s interest in social influence stemmed in part from his desire to understand how the presence of a powerful person—particularly the German dictator Adolf Hitler who ordered the killing of millions of people during World War II—could produce obedience. Under Hitler’s direction, the German SS troops oversaw the execution of 6 million Jewish people as well as other “undesirables,” including political and religious dissidents, gay people, mentally and physically disabled people, and prisoners of war. Milgram used newspaper ads to recruit men (and in one study, women) from a wide variety of backgrounds to participate in his research. When the research participant arrived at the lab, he or she was introduced to a man who the participant believed was another research participant but who was actually an experimental confederate. The experimenter explained that the goal of the research was to study the effects of punishment on learning. After the participant and the confederate both consented to participate in the study, the researcher explained that one of them would be randomly assigned to be the teacher and the other the learner. They were each given a slip of paper and asked to open it and to indicate what it said. In fact both papers read teacher, which allowed the confederate to pretend that he had been assigned to be the learner and thus to assure that the actual participant was always the teacher. While the research participant (now the teacher) looked on, the learner was taken into the adjoining shock room and strapped to an electrode that was to deliver the punishment. The experimenter explained that the teacher’s job would be to sit in the control room and to read a list of word pairs to the learner. After the teacher read the list once, it would be the learner’s job to remember which words went together. For instance, if the word pair was blue-sofa, the teacher would say the word blue on the testing trials and the learner would have to indicate which of four possible words (house, sofa, cat, or carpet) was the correct answer by pressing one of four buttons in front of him. After the experimenter gave the “teacher” a sample shock (which was said to be at 45 volts) to demonstrate that the shocks really were painful, the experiment began. The research participant first read the list of words to the learner and then began testing him on his learning.

The shock panel, as shown in Figure 6.9, “The Shock Apparatus Used in Milgram’s Obedience Study,” was presented in front of the teacher, and the learner was not visible in the shock room. The experimenter sat behind the teacher and explained to him that each time the learner made a mistake the teacher was to press one of the shock switches to administer the shock. They were to begin with the smallest possible shock (15 volts) but with each mistake the shock was to increased by one level (an additional 15 volts).

Once the learner (who was, of course, actually an experimental confederate) was alone in the shock room, he unstrapped himself from the shock machine and brought out a tape recorder that he used to play a prerecorded series of responses that the teacher could hear through the wall of the room. As you can see in Table 5.1.1,”The Schedule of Confederate’s Protest in the Milgram Experiments,” the teacher heard the learner say “ugh!” after the first few shocks. After the next few mistakes, when the shock level reached 150 volts, the learner was heard to exclaim “Get me out of here, please. My heart’s starting to bother me. I refuse to go on. Let me out!” As the shock reached about 270 volts, the learner’s protests became more vehement, and after 300 volts the learner proclaimed that he was not going to answer any more questions. From 330 volts and up the learner was silent. The experimenter responded to participants’ questions at this point, if they asked any, with a scripted response indicating that they should continue reading the questions and applying increasing shock when the learner did not respond.

| 75 volts | Ugh! |

|---|---|

| 90 volts | Ugh! |

| 105 volts | Ugh! (louder) |

| 120 volts | Ugh! Hey, this really hurts. |

| 135 volts | Ugh!! |

| 150 volts | Ugh!! Experimenter! That’s all. Get me out of here. I told you I had heart trouble. My heart’s starting to bother me now. Get me out of here, please. My heart’s starting to bother me. I refuse to go on. Let me out! |

| 165 volts | Ugh! Let me out! (shouting) |

| 180 volts | Ugh! I can’t stand the pain. Let me out of here! (shouting) |

| 195 volts | Ugh! Let me out of here! Let me out of here! My heart’s bothering me. Let me out of here! You have no right to keep me here! Let me out! Let me out of here! Let me out! Let me out of here! My heart’s bothering me. Let me out! Let me out! |

| 210 volts | Ugh!! Experimenter! Get me out of here. I’ve had enough. I won’t be in the experiment any more. |

| 225 volts | Ugh! |

| 240 volts | Ugh! |

| 255 volts | Ugh! Get me out of here. |

| 270 volts | (agonized scream) Let me out of here. Let me out of here. Let me out of here. Let me out. Do you hear? Let me out of here. |

| 285 volts | (agonized scream) |

| 300 volts | (agonized scream) I absolutely refuse to answer any more. Get me out of here. You can’t hold me here. Get me out. Get me out of here. |

| 315 volts | (intensely agonized scream) Let me out of here. Let me out of here. My heart’s bothering me. Let me out, I tell you. (hysterically) Let me out of here. Let me out of here. You have no right to hold me here. Let me out! Let me out! Let me out! Let me out of here! Let me out! Let me out! |

Before Milgram conducted his study, he described the procedure to three groups—college students, middle-class adults, and psychiatrists—asking each of them if they thought they would shock a participant who made sufficient errors at the highest end of the scale (450 volts). One hundred percent of all three groups thought they would not do so. He then asked them what percentage of “other people” would be likely to use the highest end of the shock scale, at which point the three groups demonstrated remarkable consistency by all producing (rather optimistic) estimates of around 1% to 2%.

The results of the actual experiments were themselves quite shocking. Although all of the participants gave the initial mild levels of shock, responses varied after that. Some refused to continue after about 150 volts, despite the insistence of the experimenter to continue to increase the shock level. Still others, however, continued to present the questions, and to administer the shocks, under the pressure of the experimenter, who demanded that they continue. In the end, 65% of the participants continued giving the shock to the learner all the way up to the 450 volts maximum, even though that shock was marked as “danger: severe shock,” and there had been no response heard from the participant for several trials. In sum, almost two-thirds of the men who participated had, as far as they knew, shocked another person to death, all as part of a supposed experiment on learning.

Studies similar to Milgram’s findings have since been conducted all over the world (Blass, 1999), with obedience rates ranging from a high of 90% in Spain and the Netherlands (Meeus & Raaijmakers, 1986) to a low of 16% among Australian women (Kilham & Mann, 1974). In case you are thinking that such high levels of obedience would not be observed in today’s modern culture, there is evidence that they would be. Recently, Milgram’s results were almost exactly replicated, using men and women from a wide variety of ethnic groups, in a study conducted by Jerry Burger at Santa Clara University. In this replication of the Milgram experiment, 65% of the men and 73% of the women agreed to administer increasingly painful electric shocks when they were ordered to by an authority figure (Burger, 2009). In the replication, however, the participants were not allowed to go beyond the 150 volt shock switch.

Although it might be tempting to conclude that Milgram’s experiments demonstrate that people are innately evil creatures who are ready to shock others to death, Milgram did not believe that this was the case. Rather, he felt that it was the social situation, and not the people themselves, that was responsible for the behavior. To demonstrate this, Milgram conducted research that explored a number of variations on his original procedure, each of which demonstrated that changes in the situation could dramatically influence the amount of obedience. These variations are summarized in Figure 5.1.2.

| Experimental Replication | Description | Percent Obedience |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | Initial study: Yale University men and women | 65 |

| Experiment 10 | The study is conducted off campus, in Bridgeport CT | 48 |

| Experiment 3 | The teacher is in the same room as the learner | 40 |

| Experiment 4 | The participant must hold the learner’s hand on the shock pad | 20 |

| Experiment 7 | The experimenter communicates by phone from another room | 20 |

| Experiment 13 | An “ordinary man” (presumably another research participants refuse to give shock | 20 |

| Experiment 17 | Two other research participants refuse to give shock | 10 |

| Experiment 11 | The teacher chooses his own preferred shock level | 0 |

| Experiment 15 | One experimenter indicates that the participant should not shock | 0 |

This figure presents the percentage of participants in Stanley Milgram’s (1974) studies on obedience who were maximally obedient (that is, who gave all 450 volts of shock) in some of the variations that he conducted. In the initial study, the authority’s status and power was maximized—the experimenter had been introduced as a respected scientist at a respected university. However, in replications of the study in which the experimenter’s authority was decreased, obedience also declined. In one replication the status of the experimenter was reduced by having the experiment take place in a building located in Bridgeport, Connecticut, rather than at the labs on the Yale University campus, and the research was ostensibly sponsored by a private commercial research firm instead of by the university. In this study, less obedience was observed (only 48% of the participants delivered the maximum shock). Full obedience was also reduced (to 20%) when the experimenter’s ability to express his authority was limited by having him sit in an adjoining room and communicate to the teacher by telephone. And when the experimenter left the room and had another student (actually a confederate) give the instructions for him, obedience was also reduced to 20%.

In addition to the role of authority, Milgram’s studies also confirmed the role of unanimity in producing obedience. When another research participant (again an experimental confederate) began by giving the shocks but then later refused to continue and the participant was asked to take over, only 10% were obedient. And if two experimenters were present but only one proposed shocking while the other argued for stopping the shocks, all the research participants took the more benevolent advice and did not shock. But perhaps most telling were the studies in which Milgram allowed the participants to choose their own shock levels or in which one of the experimenters suggested that they should not actually use the shock machine. In these situations, there was virtually no shocking. These conditions show that people do not like to harm others, and when given a choice they will not. On the other hand, the social situation can create powerful, and potentially deadly, social influence.

Expert Power

Expert power comes from knowledge, skill, or expertise that a group member possesses and other group members do not. For example, even though all the workers in the Social Media Relations Department have experience with computers, the information technology (IT) officer has expert power when it comes to computer networking and programming. Because of this, even though the director may have a higher status, she or he must defer to the IT officer when the office network crashes. A leader who has legitimate and expert power may be able to take a central role in setting the group’s direction, contributing to problem solving, and helping the group achieve its goal. In groups with a designated leader who relies primarily on legitimate power, a member with a significant amount of expert power may emerge as an unofficial secondary leader.

Referent Power

Referent power comes from the attractiveness, likeability, and charisma of the group member. As we learned earlier, more physically attractive people and more outgoing people are often chosen as leaders. This could be due to their referent power. Referent power also derives from a person’s reputation. A group member may have referent power if he or she is well respected outside of the group for previous accomplishments or even because he or she is known as a dependable and capable group member. Like legitimate power, the fact that a person possesses referent power doesn’t mean he or she has the talent, skill, or other characteristic needed to actually lead the group. A person could just be likable but have no relevant knowledge about the group’s task or leadership experience. Some groups actually desire this type of leader, especially if the person is meant to attract external attention and serve as more of a “figurehead” than a regularly functioning group member. For example, a group formed to raise funds for a science and nature museum may choose a former mayor, local celebrity, or NASA astronaut as their leader because of his or her referent power. In this situation it would probably be best for the group to have a secondary leader who attends to task and problem-solving functions within the group.

Information Power

Information power comes from a person’s ability to access information that comes through informal channels and well-established social and professional networks. We have already learned that information networks are an important part of a group’s structure and can affect a group’s access to various resources. When a group member is said to have “know how,” they possess information power. The knowledge may not always be official, but it helps the group solve problems and get things done. Individuals develop information power through years of interacting with others, making connections, and building and maintaining interpersonal and instrumental relationships. For example, the group formed to raise funds for the science and nature museum may need to draw on informal information networks to get leads on potential donors, to get information about what local science teachers would recommend for exhibits, or to book a band willing to perform for free at a fundraising concert.

Reward and Coercive Power

The final two types of power, reward and coercive, are related. Reward power comes from the ability of a group member to provide a positive incentive as a compliance-gaining strategy, and coercive power comes from the ability of a group member to provide a negative incentive. These two types of power can be difficult for leaders and other group members to manage, because their use can lead to interpersonal conflict. Reward power can be used by nearly any group member if he or she gives another group member positive feedback on an idea, an appreciation card for hard work, or a pat on the back. Because of limited resources, many leaders are frustrated by their inability to give worthwhile tangible rewards to group members such as prizes, bonuses, or raises. Additionally, the use of reward power may seem corny or paternalistic to some or may arouse accusations of favoritism or jealousy among group members who don’t receive the award.

Coercive power, since it entails punishment or negative incentive, can lead to interpersonal conflict and a negative group climate if it is overused or used improperly. While any leader or group member could make threats to others, leaders with legitimate power are typically in the best position to use coercive power. In such cases, coercive power may manifest in loss of pay and/or privileges, being excluded from the group, or being fired (if the group work is job related). In many volunteer groups or groups that lack formal rules and procedures, leaders have a more difficult time using coercive power, since they can’t issue official punishments. Instead, coercive power will likely take the form of interpersonal punishments such as ignoring group members or excluding them from group activities.

“Getting Real”

Leadership as the Foundation of a Career

As we’ve already learned, leaders share traits, some more innate and naturally tapped into than others. Successful leaders also develop and refine leadership skills and behaviors that they are not “born with.” Since much of leadership is skill and behavior based, it is never too early to start developing yourself as a leader. Whether you are planning to start your first career path fresh out of college, you’ve returned to college in order to switch career paths, or you’re in college to help you advance more quickly in your current career path, you should have already been working on your leadership skills for years; it’s not something you want to start your first day on the new job. Since leaders must be able to draw from a wealth of personal experience in order to solve problems, relate to others, and motivate others to achieve a task, you should start to seek out leadership positions in school and/or community groups. Since you may not yet be sure of your exact career path, try to get a variety of positions over a few years that are generally transferrable to professional contexts. In these roles, work on building a reputation as an ethical leader and as a leader who takes responsibility rather than playing the “blame game.” Leaders still have to be good team players and often have to take on roles and responsibilities that other group members do not want. Instead of complaining or expecting recognition for your “extra work,” accept these responsibilities enthusiastically and be prepared for your hard work to go unnoticed. Much of what a good leader does occurs in the background and isn’t publicly praised or acknowledged. Even when the group succeeds because of your hard work as the leader, you still have to be willing to share that praise with others who helped, because even though you may have worked the hardest, you didn’t do it alone.

As you build up your experience and reputation as a leader, be prepared for your workload to grow and your interpersonal communication competence to become more important. Once you’re in your career path, you can draw on this previous leadership experience and volunteer or step up when the need arises, which can help you get noticed. Of course, you have to be able to follow through on your commitment, which takes discipline and dedication. While you may be excited to prove your leadership chops in your new career path, I caution you about taking on too much too fast. It’s easy for a young and/or new member of a work team to become overcommitted, as more experienced group members are excited to have a person to share some of their work responsibilities with. Hopefully, your previous leadership experience will give you confidence that your group members will notice. People are attracted to confidence and want to follow people who exhibit it. Aside from confidence, good leaders also develop dynamism, which is a set of communication behaviors that conveys enthusiasm and creates an energetic and positive climate. Once confidence and dynamism have attracted a good team of people, good leaders facilitate quality interaction among group members, build cohesion, and capitalize on the synergy of group communication in order to come up with forward-thinking solutions to problems. Good leaders also continue to build skills in order to become better leaders. Leaders are excellent observers of human behavior and are able to assess situations using contextual clues and nonverbal communication. They can then use this knowledge to adapt their communication to the situation. Leaders also have a high degree of emotional intelligence, which allows them to better sense, understand, and respond to others’ emotions and to have more control over their own displays of emotions. Last, good leaders further their careers by being reflexive and regularly evaluating their strengths and weaknesses as a leader. Since our perceptions are often skewed, it’s also good to have colleagues and mentors/supervisors give you formal evaluations of your job performance, making explicit comments about leadership behaviors. As you can see, the work of a leader only grows more complex as one moves further along a career path. But with the skills gained through many years of increasingly challenging leadership roles, a leader can adapt to and manage this increasing complexity.

- What leadership positions have you had so far? In what ways might they prepare you for more complex and career-specific leadership positions you may have later?

- What communication competencies do you think are most important for a leader to have and why? How do you rate in terms of the competencies you ranked as most important?

- Who do you know who would be able to give you constructive feedback on your leadership skills? What do you think this person would say? (You may want to consider actually asking the person for feedback).

Key Takeaways

- Leaders fulfill a group role that is associated with status and power within the group that may be formally or informally recognized by people inside and/or outside of the group. While there are usually only one or two official leaders within a group, all group members can perform leadership functions, which are a complex of beliefs, communication patterns, and behaviors that influence the functioning of a group and move a group toward the completion of its tasks.

-

Leaders can adopt a directive, participative, supportive, or achievement-oriented style.

- Directive leaders help provide psychological structure for their group members by clearly communicating expectations, keeping a schedule and agenda, providing specific guidance as group members work toward the completion of their task, and taking the lead on setting and communicating group rules and procedures.

- Participative leaders work to include group members in the decision-making process by soliciting and considering their opinions and suggestions.

- Supportive leaders show concern for their followers’ needs and emotions.

- Achievement-oriented leaders strive for excellence and set challenging goals, constantly seeking improvement and exhibiting confidence that group members can meet their high expectations.

-

Leaders and other group members move their groups toward success and/or the completion of their task by tapping into various types of power.

- Legitimate power flows from the officially recognized power, status, or title of a group member.

- Expert power comes from knowledge, skill, or expertise that a group member possesses and other group members do not.

- Referent power comes from the attractiveness, likeability, and charisma of the group member.

- Information power comes from a person’s ability to access information that comes through informal channels and well-established social and professional networks.

- Reward power comes from the ability of a group member to provide a positive incentive as a compliance-gaining strategy, and coercive power comes from the ability of a group member to provide a negative incentive (punishment).

Exercises

- Think of a leader that you currently work with or have worked with who made a strong (positive or negative) impression on you. Which leadership style did he or she use most frequently? Cite specific communication behaviors to back up your analysis.

- Getting integrated: Teachers are often viewed as leaders in academic contexts along with bosses/managers in professional, politicians/elected officials in civic, and parents in personal contexts. For each of these leaders and contexts, identify some important leadership qualities that each should possess, and discuss some of the influences in each context that may affect the leader and his or her leadership style.

References

Bormann, E. G., and Nancy C. Bormann, Effective Small Group Communication, 4th ed. (Santa Rosa, CA: Burgess CA, 1988), 130–33.

Cragan, J. F., and David W. Wright, Communication in Small Group Discussions: An Integrated Approach, 3rd ed. (St. Paul, MN: West Publishing, 1991), 120.

Deutschman, A., “Exit the King,” The Daily Beast, September 21, 2011, accessed August 23, 2012, http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2011/08/28/steve-jobs-american-genius.html.

Fiedler, F. E., A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967).

French Jr., J. R. P., and Bertram Raven, “The Bases of Social Power,” in Studies in Social Power, ed. Dorwin Cartwright (Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, 1959), 150–67.

Hargie, O., Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (London: Routledge, 2011), 456.

House, R. J., and Terrence R. Mitchell, “Path-Goal Theory of Leadership,” Journal of Contemporary Business 3 (1974): 81–97.

House, R. J., and Terrence R. Mitchell, “Path-Goal Theory of Leadership: Lessons, Legacy, and a Reformulated Theory,” The Leadership Quarterly, 7, no. 3 (1996): 323-352. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(96)90024-7.

Lewin, K., Ronald Lippitt, and Ralph K. White, “Patterns of Aggressive Behavior in Experimentally Created ‘Social Climates,’” Journal of Social Psychology 10, no. 2 (1939): 269–99.

Pavitt, C., “Theorizing about the Group Communication-Leadership Relationship,” in The Handbook of Group Communication Theory and Research, ed. Lawrence R. Frey (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999), 313.

Wood, J. T., “Leading in Purposive Discussions: A Study of Adaptive Behavior,” Communication Monographs 44, no. 2 (1977): 152–65.

A group role that is associated with a high-status position and may be formally or informally recognized by group members

The complexity of beliefs, communication patterns, and behaviors that influence the functioning of a group and move toward the completion of its task

Leaders who help provide psychological structure for their group members by clearly communicating expectations, keeping a schedule and agenda, providing specific guidance as group members work toward the completion of their task, and taking the lead on setting and communicating group rules and procedures

Leaders who work to include group members in the decision-making process by soliciting and considering opinions and suggestions

Leaders who show concern for their followers’ needs and emotions

Leaders who strive for excellence and set challenging goals, constantly seeking improvement and exhibiting confidence that group members can meet their high expectations

Power that flows from the officially recognized position, status, or title, of a group member

Power that comes from knowledge, skill, or expertise that a group member possesses and other group members do not

Power that comes from the attractiveness, likeability, and charisma of the group member

Power that comes from a person’s ability to access information that comes through informal channels and well-established social and professional networks

Power that comes from a group member to provide a positive incentive as a compliance-gaining strategy

Power that comes from the ability of a group member to provide a negative incentive; for example, “vote for me, or else…”