Quality Qualitative Data

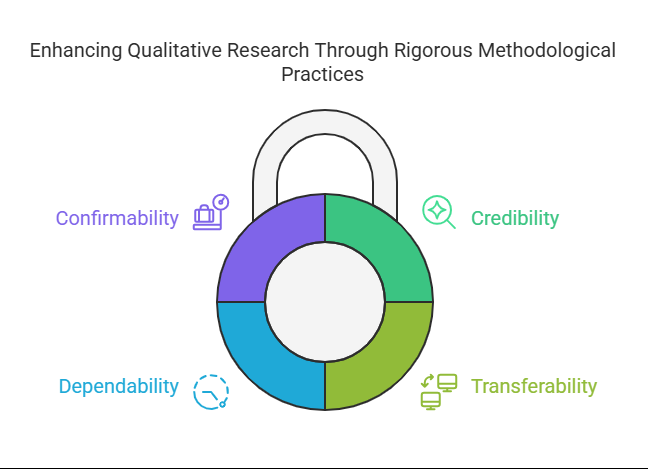

In qualitative research, the ideas of reliability and validity used in quantitative studies are often adjusted to better fit the nature of qualitative inquiry. Because qualitative research focuses on understanding human experiences, perceptions, and social interactions, researchers emphasize ensuring their findings are trustworthy rather than relying on statistical measures. Lincoln and Guba (1985) developed a widely accepted framework that adapts these concepts for qualitative research. Their framework includes four key elements: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. These criteria help ensure that qualitative research is thorough, meaningful and accurately represents participants’ experiences.

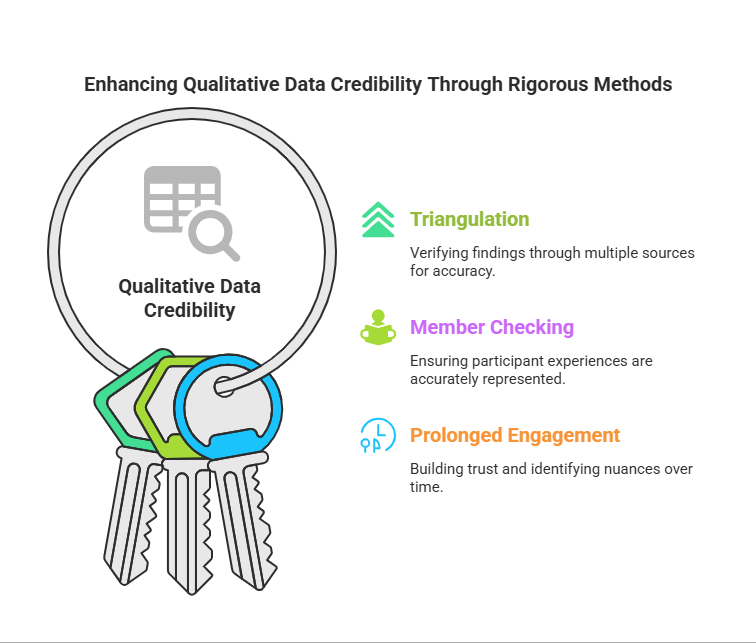

Credibility

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

Credibility refers to how accurate the findings are from the participants’ perspective. It refers to the degree to which the findings of a study accurately represent the experiences and meanings conveyed by the participants. Researchers enhance credibility through various techniques such as triangulation, member checking, and prolonged engagement. Since credibility in qualitative research is so important, let’s discuss each of these in more detail.

Triangulation in research is like fact-checking from multiple sources to make sure the findings are accurate and reliable. Instead of relying on just one method, one perspective, or one set of data, researchers use different approaches to cross-check their results.

For example, if you were trying to understand a person’s daily routine, you wouldn’t just ask them—you might also observe their actions, check their schedule, and talk to people who know them. If all these sources tell a similar story, you can be more confident that your findings are accurate.

In research, triangulation can happen in different ways:

- Method Triangulation – Using different ways to collect data (e.g., interviews, surveys, observations).

- Data Triangulation – Gathering information from different people, places, or times.

- Investigator Triangulation – Having multiple researchers analyze the same data to reduce bias.

- Theoretical Triangulation – Looking at the data through different theories or perspectives.

By using triangulation, researchers help ensure that their findings are trustworthy, well-rounded, and not based on just one point of view.

Member checking allows participants to review and validate interpretations, ensuring that their experiences are accurately portrayed. Researchers go back to the people they’ve studied (the participants) to ask if their findings or interpretations accurately reflect the participants’ experiences or views. It’s a way for researchers to ensure their conclusions are correct and trustworthy. In simple terms, it’s like double-checking with the people involved to make sure the story you’re telling about them is accurate.

For example, imagine you’re a researcher studying how students feel about online learning. After interviewing several students, you write a report of their experiences and feelings. Before finalizing the report, you return to the students and ask, “Is this an accurate reflection of what you told me? Did I miss anything important?” This gives the students the chance to indicate if something needs to be changed or added. After this interaction, the researcher can revise the report to more accurately represent the student’s experiences with online learning. This step helps ensure your research findings truly represent the participants’ perspectives.

Prolonged engagement is a technique used in qualitative research where the researcher spends an extended period of time in the research setting or with participants to build trust, identify patterns and subtle nuances, reduce researcher bias, and distinguish between genuine behaviors and those influenced by the researcher’s presence (also known as the Hawthorne effect). Instead of gathering data quickly, the researcher immerses themselves in the environment to ensure accurate data collection. By investing time in the setting, researchers gain a deeper, more authentic understanding of participants’ experiences.

For example, imagine a researcher studying how homeless youth navigate daily life. If they only conduct a one-time interview, they might receive surface-level answers because participants do not fully trust them yet or because the researcher lacks context about their real challenges. Instead, through prolonged engagement, the researcher spends several months volunteering at a youth shelter, building relationships with participants. Observing interactions over time gives them insight into real-life struggles beyond what is expressed in interviews. Because the researcher invests significant time in the setting, they develop a more complete and trustworthy understanding of the participants’ experiences.

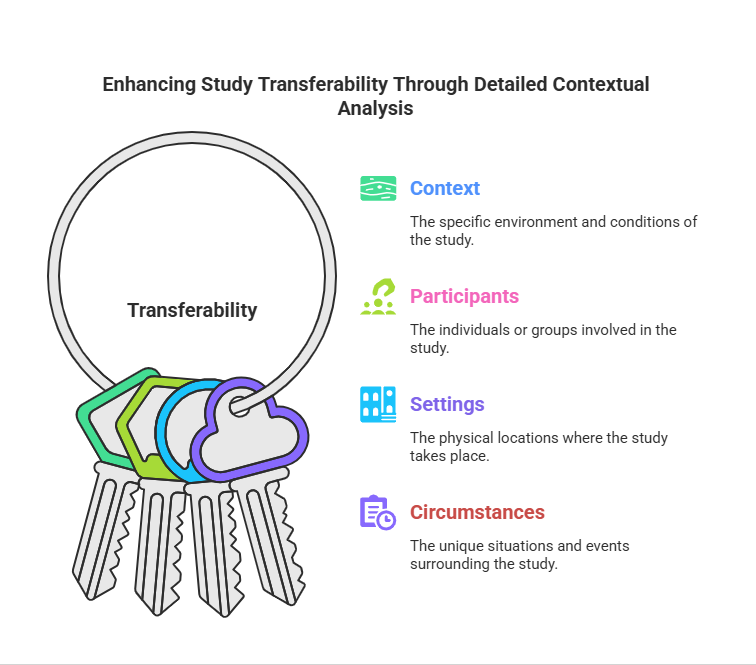

Transferability

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

In qualitative research, transferability refers to how well study findings can be applied to other settings or groups. The key to enhancing the transferability of a study is to provide a thick description of the specific contexts, participants, settings, and circumstances of the study (Braum & Clarke, 2013). While quantitative research seeks universal patterns, qualitative research prioritizes understanding specific experiences, meanings, and perspectives (Tracey, 2010). The user of the research plays a key role in evaluating whether the findings apply to their own setting, rather than the researcher making claims about broad applicability (Shenton, 2004). This means that the reader must determine whether their own context and conditions are sufficiently similar to those of the original study to justify applying its findings to their situation. Transferability allows qualitative research to be meaningful beyond its immediate setting, provided that the researcher offers enough detail for readers to determine its relevance to their own circumstances.

For example, imagine a researcher studying burnout among child life specialists in large pediatric hospitals and providing detailed descriptions of factors such as patient caseload, interdisciplinary team dynamics, emotional demands, and institutional support. If another researcher or a child life program coordinator in a smaller community hospital or outpatient setting reads the study, they can assess whether similar challenges exist in their own work environment and whether the findings are relevant to their specialists.

The original study does not claim to be universally applicable but by offering thick descriptions and contextual details, it allows others to determine whether the findings resonate with their specific settings and professional experiences.

Dependability

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

Dependability in qualitative research concerns the consistency of a study’s findings over time and across different conditions (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Merriam and Tisdell (2016) explain that because qualitative research is dynamic and interpretive, dependability does not require exact replication but instead emphasizes stability and coherence in the research process. To enhance dependability, researchers maintain audit trails, which are comprehensive records detailing the research design, data collection methods, coding procedures, and analytical decisions (Shenton, 2004). These detailed records enable other researchers to follow the reasoning behind the study’s findings and confirm that conclusions were derived through a logical and systematic process (Nowell et al., 2017).

Another strategy for ensuring dependability is peer debriefing, where researchers discuss their methods and findings with colleagues or external experts to identify potential biases and refine interpretations (Creswell & Poth, 2018). These discussions strengthen the overall credibility and trustworthiness of the study by ensuring that findings are not solely influenced by the researcher’s subjective perspective (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

For example, if a researcher is conducting a study on parental stress among families with children with autism. To ensure dependability, they would need to keep detailed notes on their interview process, thematic coding decisions, and any methodological adjustments made throughout the study. They would also need to maintain an audit trail that includes transcriptions, coding memos, and reflexive journal entries documenting how their interpretations evolved. Additionally, they should engage in peer debriefing by discussing emerging themes with fellow researchers who specialize in family stress, autism spectrum disorder, or parenting research. These colleagues provide feedback, challenge assumptions, and help ensure that the study’s findings are consistent, well-reasoned, and free from unexamined bias.

By incorporating audit trails and peer debriefing, the researcher enhances the dependability of their study, making it possible for others to trace the decision-making process and evaluate the trustworthiness of the findings.

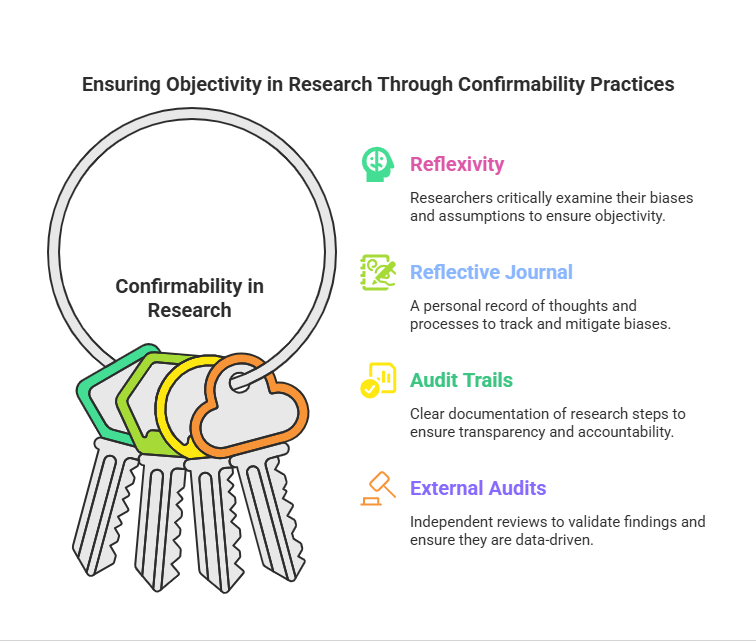

Confirmability

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

Confirmability in qualitative research refers to the extent to which a study’s findings are shaped by participants’ experiences rather than the researcher’s personal biases or motivations (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Since all researchers inevitably bring their own perspectives and preconceptions to a study, ensuring confirmability requires transparency in data collection, analysis, and interpretation (Nowell et al., 2017).

One essential technique for enhancing confirmability is reflexivity, where researchers critically examine their own biases, assumptions, and potential influence on the research process (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). A common reflexivity practice is maintaining a reflective journal in which researchers document their thoughts, decisions, and any possible biases throughout the study (Shenton, 2004). Audit trails can also help establish confirmability by providing a clear record of the steps taken to arrive at the study’s conclusions (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Researchers may also wish to employ external audits to ensure confirmability. External audits allow an independent reviewer to evaluate the research process to ensure that findings are based on data rather than researcher assumptions (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

For example, imagine a researcher conducting a study on how parents of LGBTQ+ youth navigate family acceptance, societal pressures, and support systems. To ensure confirmability, the researcher keeps a reflective journal, documenting their own thoughts, assumptions, and potential biases to minimize personal influence on the findings. They also maintain a detailed audit trail, including interview transcripts, coding notes, and decision-making records, ensuring transparency in how themes and conclusions were developed. Additionally, the researcher invites an independent colleague specializing in LGBTQ+ family dynamics to conduct an external audit, reviewing the research process to verify that the findings accurately represent the participants’ experiences rather than being shaped by the researcher’s personal perspectives.

By using reflexivity, audit trails, and external audits, the researcher ensures that their study authentically reflects the voices of parents and LGBTQ+ youth rather than being influenced by personal beliefs or societal expectations. These strategies enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of the research, making it a valuable contribution to understanding family experiences within the LGBTQ+ community.

Establishing Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

You will have noticed that trustworthiness plays a key component in the acceptance of qualitative research as being reliable and valid. While qualitative research cannot make the same claims as quantitative research regarding reliability and validity, by incorporating credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability into the research process, qualitative scholars attempt to ensure that their studies are methodologically sound and ethically responsible. Unlike quantitative research, which relies on statistical tests to verify reliability and validity, qualitative research depends on thorough documentation, participant involvement, and thoughtful interpretation to establish trustworthiness. Understanding these concepts allows researchers to design studies that are transparent, replicable in spirit, and deeply meaningful in their findings. Understanding these concepts enables researchers to design transparent studies which are methodologically sound and rich in meaning. While qualitative research does not aim to establish universal truths, its rigor ensures that the knowledge produced is credible, insightful, and applicable across various contexts.

References

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. SAGE.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851.