Ethical Considerations

The act of bringing together people’s stories through qualitative research is not an easy one and shouldn’t be taken lightly. In qualitative research we have an ethical responsibility to treat what is shared by participants with a sense of respect as we interpret and find meaning in their words. This includes making conscientious efforts not to twist, change, or subvert the meaning of the data, and informing participants early on about how their data will be analyzed. This section will describe ethical considerations in more detail, including the role of the researcher in the data analysis process.

A deep understanding of cultural context as we make sense of meaning

Similar to the ethical considerations we need to keep in mind as we deconstruct stories, we also need to work diligently to understand the cultural context in which these stories are shared. This requires that we approach the task of analysis with a sense of cultural humility, meaning that we don’t assume that our perspective or worldview as the researcher is the same as our participants. Their life experiences may be quite different from our own, and because of this, the meaning in their stories may be very different than what we might initially expect.

As such, we need to ask questions to better understand words, phrases, ideas, gestures, etc. that seem to have particular significance to participants. We also can use activities like member checking, another tool to support qualitative rigor, to ensure that our findings are accurately interpreted by vetting them with participants prior to the study conclusion. We can spend a good amount of time getting to know the groups and communities that we work with, paying attention to their values, priorities, practices, norms, strengths, and challenges. Finally, we can actively work to challenge more traditional methods research and support more participatory models that advance community co-researchers or consistent oversight of research by community advisory groups to inform, challenge, and advance this process; thus elevating the wisdom of community members and their influence (and power) in the research process.

How are participants present in the analysis process; What power or influence do they have

Remember, research is political. We need to consider that our findings represent ideas that are shared with us by living and breathing human beings and often the groups and communities that they represent. They have been gracious enough to share their time and their stories with us, yet they often have a limited role once we gather data from them. They are essentially putting their trust in us that we won’t be misrepresenting or culturally appropriating their stories in ways that will be harmful, damaging, or demeaning. Elliot (2016)[5] discusses the problems of “damaged-centered” research, which is research that portrays groups of people or communities as flawed, surrounded by problems, or incapable of producing change. Her work specifically references the way research and media have often portrayed people from the Appalachian region, and how these influences have perpetuated, reinforced, and even created stereotypes that these communities face. We need to thoughtfully consider how the research we are involved in will reflect on our participants and their communities.

Now, some research approaches, particularly participatory approaches, suggest that participants should be trained and actively engaged throughout the research process, helping to shape how our findings are presented and how the target population is portrayed. Implementing a participatory approach requires academic researchers to give up some of their power and control to community co-researchers. Ideally these co-researchers provide their input and are active members in determining what the findings are and interpreting why/how they are important. I believe this is a standard we need to strive for. However, this is the exception, not the rule. As such, if you are participating in a more traditional research role where community participants are not actively engaged, whenever possible, it is good practice to find ways to allow participants or other representatives to help lend their validation to our findings. While to a smaller extent, these opportunities suggest ways that community members can be empowered during the research process (and researchers can turn over some of our control). You may do this through activities like consulting with community representatives early and often during the analysis process and using member checking (referenced above and in our chapter on qualitative rigor) to help review and refine results. These are distinct and important roles for the community and do not mean that community members become researchers; but that they lend their perspectives in helping the researcher to interpret their findings.

The bringing together of voices: What does this represent and to whom

Qualitative research generally involves a relatively small number of participants (or even a single person) sharing their stories. As researchers, we then bring together this data in the analysis phase in an attempt to tell a broader story about the issue we are studying. Our findings often reflect commonalities and patterns, but also should highlight contradictions, tensions, and dissension about the topic.

Before beginning your data analysis, think about what the findings for your research proposal might represent. Here are a few questions you might ask yourself about the results of your study:

- What do they represent to you as a researcher?

- What do they represent to participants directly involved in your study?

- What do they represent to the families of these participants?

- What do they represent to the groups and communities that represent or are connected to your population?

For each of these perspectives, there is no single answer. As a student researcher, your study might represent a grade, an opportunity to learn more about a topic you are interested in, and a chance to hone your skills as a researcher. For participants, the findings might represent a chance to share their input or frustration that they are being misrepresented. Community members might view the research findings with skepticism that research produces any kind of change or anger that findings bring unwanted attention to the community. Obviously we can’t foretell all the answers to these questions, but thinking about them can help us to thoughtfully and carefully consider how we go about collecting, analyzing and presenting our data. We certainly need to be honest and transparent in our data analysis, but additionally, we need to consider how our analysis impacts others. It is especially important that we anticipate this and integrate it early into our efforts to educate our participants on what the research will involve, including potential risks.

Accounting for our influence in the analysis process

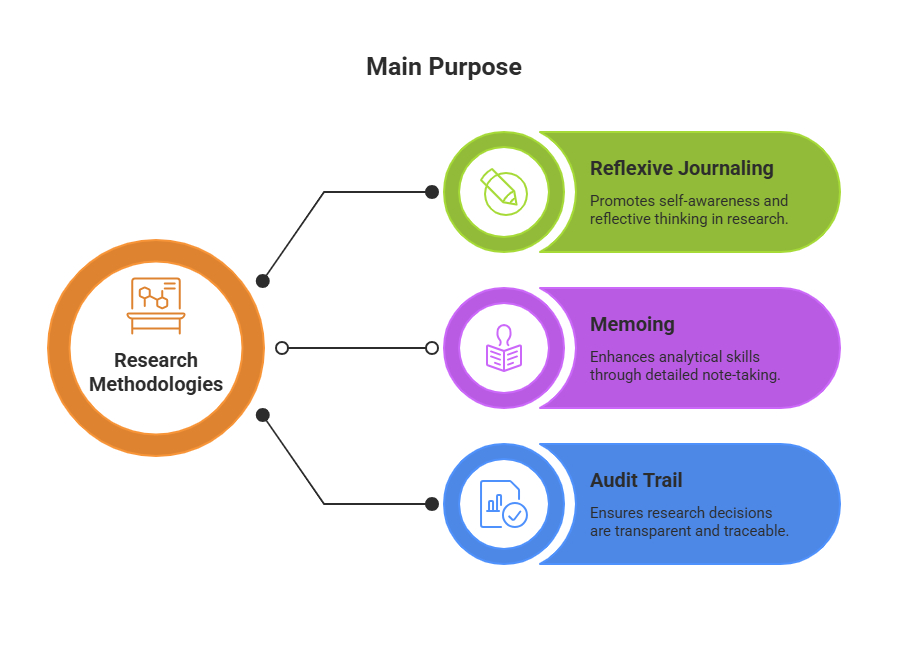

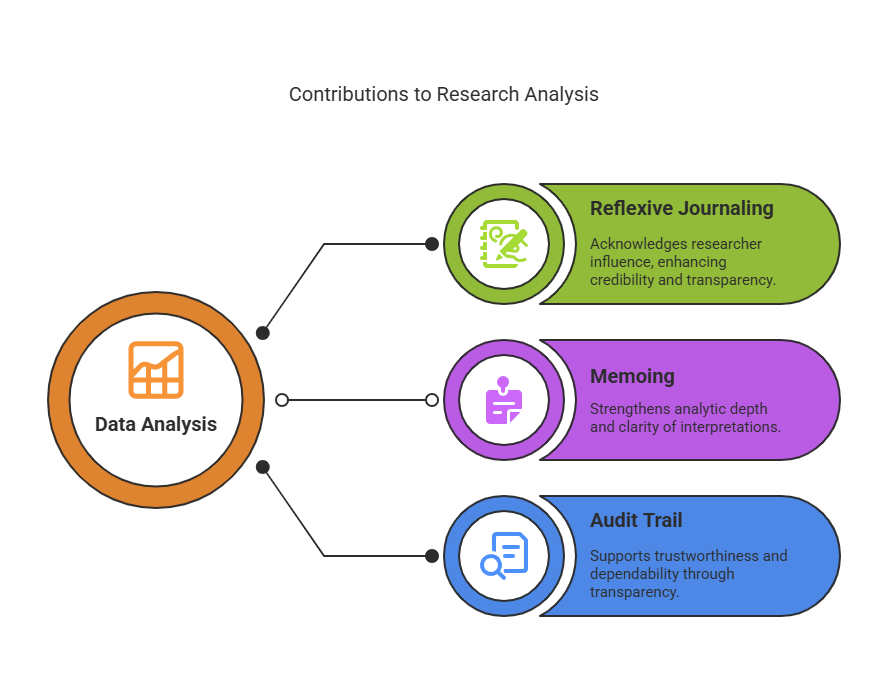

Along with our ethical responsibility to our research participants, we also have an accountability to research consumers, the scientific community at large, and other stakeholders in our qualitative research. As qualitative researchers (or quantitative researchers, for that matter), people should expect that we have attempted, to the best of our abilities, to account for our role in the research process. This is especially true in analysis. Our finding should not emerge from some ‘black box’, where raw data goes in and findings pop out the other side, with no indication of how we arrive at them. Thus, an important part of rigor is transparency and the use of tools such as writing in reflexive journals, memoing, and creating an audit trail to assist us in documenting both our thought process and activities in reaching our findings.

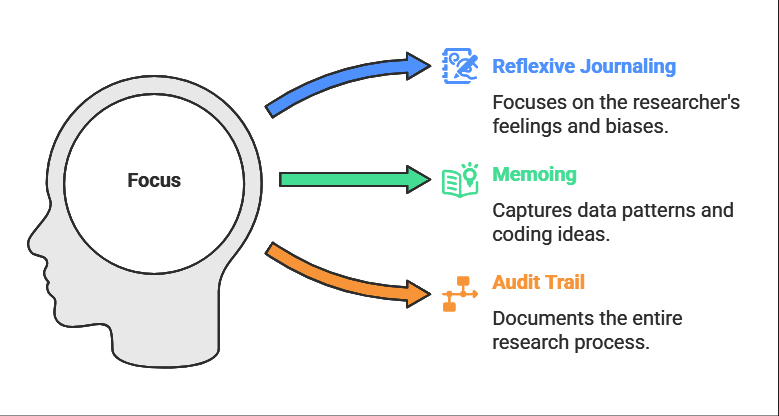

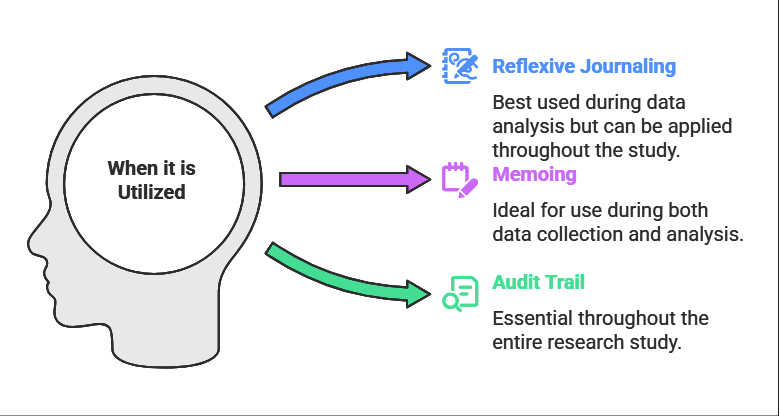

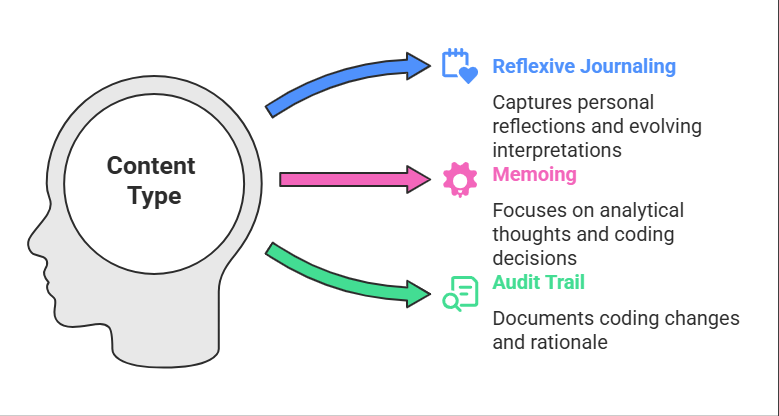

Reflexive Journaling

Reflexive journals allow researchers to record their thoughts, feelings, and assumptions. These journals aren’t just about taking notes—they’re about capturing the evolving interpretations and insights that naturally emerge during a study. The use of reflexive journals is vital during data analysis. Researchers use these journals to track how their personal background, values, and interactions with participants that may shape coding decisions, theme development, and overall interpretations. This form of documentation promotes transparency and enhances the credibility of the findings by acknowledging the human element inherent in qualitative inquiry. Reflexive journaling contributes to trustworthiness and is a crucial component of the analytical process. With this in mind, researchers should consider reflexive journaling an essential practice within qualitative data analysis.

Memoing

Memoing is akin to reflexive journaling as they both offer the researcher a space to capture insights, interpretations, and questions about the data they are collecting. The primary difference is their purpose. Memoing is a space for the researcher to notice patterns and examine themes from data collected during interviews, observations, or other sources. As mentioned above, reflexive journaling involves observing your feelings, experiences, and beliefs, and how these things might influence the way you interpret the data. Memoing, on the other hand, focuses on understanding the information and is tightly linked to the analytical work of coding, categorizing, and theme development. Memoing helps researchers think more deeply and carefully about what they’re learning. It lets them put the pieces together in a clear way that makes sense, using both the information they’ve collected and their growing ideas about what it all means.

Audit Trail

An audit trail in qualitative research is a detailed, transparent record of the decisions, steps, and processes taken throughout a study, particularly during data analysis. It serves as a form of documentation that allows others, such as peer reviewers, advisors, or future researchers, to trace how findings were derived from the data. The audit trail includes records of coding schemes, theme development, analytic memos, reflexive journal entries, changes to the research question, and the rationale behind interpretive choices. By maintaining a comprehensive audit trail, researchers demonstrate that their analysis was systematic, thoughtful, and grounded in evidence. This transparency supports the trustworthiness and dependability of the research, providing evidence that findings are not arbitrary or solely driven by researcher bias. In short, an audit trail strengthens the credibility of qualitative analysis by making the research process visible and verifiable to others.

Distinguishing between these tools can be confusing. I hope the following images can help clarify the primary purposes, focus, utilization during data collection, content type, and contributions to data analysis of each of these tools.

*This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

References

Elliott, L. (2016, January, 16). Dangers of “damage-centered” research. The Ohio State University, College of Arts and Sciences: Appalachian Student Resources. https://u.osu.edu/appalachia/2016/01/16/dangers-of-damage-centered-research/ ↵

Image Attributions

Image 1 (black box) is from Chapter 19. A survey of approaches to qualitative data analysis – Graduate Research Methods in Social Work