Why is Measurement Important?

We’ve already talked about what makes an empirical question different from an ethical question. In an empirical question, it’s also important that we can measure, in some form or fashion, the thing we’re interested in learning about. Measurement can be very simple for some things we’re interested in (if you want to know someone’s height, you can just ask them or grab a tape measure) or it can be very complex (can you quantify happiness? What is health?). There are many different ways we measure things in the social sciences, so this is a place where creativity can be very helpful!

This chapter is mainly focused on quantitative research methods, as the level of specificity required to begin quantitative research is far greater than that of qualitative research. In quantitative research, you must specify how you define and plan to measure each concept before you can interact with your participants. Qualitative research does not reach the level of specificity and clarity required for quantitative research because your participants are the experts and definitions will emerge from how participants respond to your questions. For this reason, we will focus mostly on quantitative measurement and conceptualization in this chapter, with subsections addressing qualitative research. In quantitative research, we’re trying to make sense of the world with numbers, so you can imagine how that makes it complicated when you want to study something like parenting quality, infant temperament, or social expectations of masculinity (but not impossible!).

Recognizing and respecting the importance of measurement will be beneficial in research methods and other areas of life. Have you ever baked a cake? If you tried to bake one without measuring tools, whether or not you’ve done it before it would be unlikely to turn out very well (though you’re welcome to try it!). Knowing the goal we’re working towards and how to measure progress or input is essential to many areas of life, so consider how you “measure” most of what you do on a daily basis (for example, how do you know if you’re successful in a class? How do you know when you’re driving too fast? Can you measure how much food to give your dog?). How might that apply when thinking about research?

Measurement is critical to successful baking as well as successful social scientific research projects. In social science, measurement refers to the process by which we describe and ascribe meaning to the key facts, concepts, or other phenomena that we are investigating. At its core, measurement is about clearly and precisely defining one’s terms. Of course, measurement in social science isn’t quite as simple as using a measuring cup or spoon, but there are some basic tenants on which most social scientists agree when it comes to measurement. We’ll explore those, as well as some of the ways that measurement might vary depending on your unique approach to the study of your topic.

What do social scientists measure?

We can imagine what social scientists measure by thinking about what types of topics and populations they might study. Think about the topics you’ve learned in other social work classes or the topics you’ve considered investigating in your own research. Let’s consider Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner’s study (2011) of first graders’ mental health. To conduct that study, Milkie and Warner needed to have some idea about how they were going to measure mental health. What does mental health mean, exactly? How do we know when we’re observing someone whose mental health is good and someone whose mental health is compromised? Understanding how measurement works in research methods helps us answer these sorts of questions.

As you might have guessed, social scientists will measure just about anything that they have an interest in investigating. For example, those who are interested in learning about the correlation between social class and levels of happiness must develop some way to measure both social class and happiness. Those who wish to understand how well immigrants cope in their new locations must measure immigrant status and coping. Those who wish to understand how a person’s gender shapes their workplace experiences must measure gender and workplace experiences. You get the idea. While social scientists can measure just about anything they wish to observe or study, some things are easier to observe or measure than others.

In 1964, philosopher Abraham Kaplan (1964) wrote The Conduct of Inquiry, which has since become a classic work in research methodology (Babbie, 2010). In his text, Kaplan describes different categories of things that behavioral scientists observe. One of those categories, which Kaplan called “observational terms,” is probably the simplest to measure in social science. Observational terms are the sorts of things that we can see with the naked eye simply by looking at them. They are terms that “lend themselves to easy and confident verification” (Kaplan, 1964, p. 54). If we wanted to know how playground conditions differ across neighborhoods, then we could directly observe the variety, amount, and condition of equipment at various playgrounds.

Indirect observables, on the other hand, are less straightforward to assess. They are “terms whose application calls for relatively more subtle, complex, or indirect observations, in which inferences play an acknowledged part. Such inferences concern presumed connections, usually causal, between what is directly observed and what the term signifies” (Kaplan, 1964, p. 55). If we conducted a study that required information on participant income, we’d probably have to ask participants about their income in an interview or a survey. Thus, we have observed income, even if it has only been observed indirectly. Birthplace might be another indirect observable. We can ask study participants in the place that they were born, but chances are we won’t have directly observed any of those people being born in the locations they report.

Sometimes the measures that we are interested in are more complex and more abstract than observational terms or indirect observables. Think about some of the concepts you’ve learned about in other social classes—for example, ethnocentrism. What is ethnocentrism? Well, from completing an introductory psychology or family science class you might know that it has something to do with the way a person judges another’s culture. But how would you measure it? Here’s another construct: bureaucracy. We know this term has something to do with organizations and how they operate but measuring such a construct is trickier than measuring something like a person’s income. The theoretical notions of ethnocentrism and bureaucracy represent ideas whose meanings we have come to agree on. Though we may not be able to observe these abstractions directly, we can observe their components.

Kaplan referred to these more abstract things that behavioral scientists measure as constructs. Constructs are “not observational either directly or indirectly” (Kaplan, 1964, p. 55), but they can be defined based on observables. For example, the construct of bureaucracy could be measured by counting the number of supervisors that need to approve routine spending by public administrators. The greater the number of administrators that must sign off on routine matters, the greater the degree of bureaucracy. Similarly, we might be able to ask a person the degree to which they trust people from different cultures around the world and then assess the ethnocentrism inherent in their answers. We can measure constructs like bureaucracy and ethnocentrism by defining them in terms of what we can observe. We might think of some of these things we can observe as “symptoms” of the construct we’re interested in, similarly to how we might observe symptoms of an illness, like fever, rash, and headache to diagnose the condition. Note that these can also be positive, however: smiling, playing, and laughter might be “symptoms” of a construct called “happiness” for example.

Thus far, we have learned that social scientists measure what Kaplan called observational terms, indirect observables, and constructs. These terms refer to the different things that social scientists may be interested in measuring, but how do they measure these things?

How do social scientists measure?

Measurement in social science is a process. It occurs at multiple stages of a research project: in the planning stages, in the data collection stage, and sometimes even in the analysis stage. Recall that previously we defined measurement as the process by which we describe and ascribe meaning to the key facts, concepts, or other phenomena that we are investigating. Once we’ve identified a research question, we consider the key ideas we hope to learn from our project. In describing those key ideas, we begin the measurement process.

Let’s say that our research question is the following: How do new college students cope with the adjustment to college? In order to answer this question, we’ll need some idea about what coping means. We may come up with an idea about what coping means early in the research process, as we begin to think about what to look for (or observe) in our data-collection phase. Once we’ve collected data on coping, we also have to decide how to report on the topic. Perhaps, for example, there are different types or dimensions of coping, some of which lead to more successful adjustment than others. Regardless of how we decide to proceed and what we decide to report, measurement is important at each of these key phases in the research process.

As the preceding example demonstrates, measurement is a process because it occurs at multiple stages of conducting research. Additionally, the process of measurement itself involves multiple stages, including identifying, defining, and observing your key terms, as well as deciding whether your observations are useful. An additional step in the measurement process involves deciding what elements your measures contain. A measure’s elements might be very straightforward and clear, particularly if they are directly observable. Other measures are more complex and might require the researcher to account for different themes or types. These sorts of complexities require careful attention to a concept’s level of measurement and its dimensions. We’ll explore these complexities in greater depth at the end of this chapter, but first let’s look more closely at the early steps involved in the measurement process, starting with conceptualization.

Conceptualization

Begin to consider the “things” you might want to measure for your research question. Choose one to focus on for now if you have multiple. If you’re currently leaning toward a qualitative research question, temporarily consider a quantitative question within your topic so that you have examples to work with for this chapter.

Now consider the “thing” you’re interested in. That “thing” may be gender roles adherence, relationship stability, parenting stress, or any number of other aspects of family and individual life that you’re interested in. Whatever it is, it’s one of the variables you’re interested in measuring for your research question. A variable, which we’ll speak about more in a moment, is a numeric measure of something, and it varies (hence the name) among your research participants.

In this section, we’ll look at one of the first steps in the measurement process, which is conceptualization. This has to do with defining our terms as clearly as possible while not taking ourselves too seriously in the process. Our definitions mean only what we say they mean—nothing more and nothing less. First, we will talk about how to define our terms and later we will examine how to not take ourselves (or our terms) too seriously.

For anything we’re hoping to measure in either quantitative or qualitative research, we must consider our conceptualization of the thing, especially if it’s a construct. This is more challenging than it might seem, and we need to keep our conceptualization open to revision as we think, read, and discuss our ideas.

Concepts and conceptualization

So far, the word concept has come up quite a bit, and it is important to be sure we have a shared understanding of that term. A concept is the notion or image that we conjure up when we think of some cluster of related observations or ideas. For example, masculinity is a concept. What do you think of when you hear that word? Presumably, you imagine some set of behaviors and perhaps even a particular style of self-presentation. Of course, we can’t necessarily assume that everyone conjures up the same set of ideas or images when they hear the word masculinity. While there are many possible ways to define the term and some may be more common or have more support than others, there is no universal definition of masculinity. What counts as masculine may shift over time, from culture to culture, and even from individual to individual (Kimmel, 2008). This is why defining our concepts is so important.

You might be asking yourself why you should bother defining things if there is never a single, always-correct definition for concepts. It is important to understand definitions of concepts because when we conduct empirical research, our terms mean only what we say they mean. Without a shared understanding of this term, we have no way to know if we’re picturing the same concept. Without understanding how a researcher has defined their key concepts, it would be nearly impossible to understand the meaning of that researcher’s findings and conclusions. Thus, any decision we make based on empirical research findings should be based on full knowledge of how the research was designed and how its concepts were defined and measured.

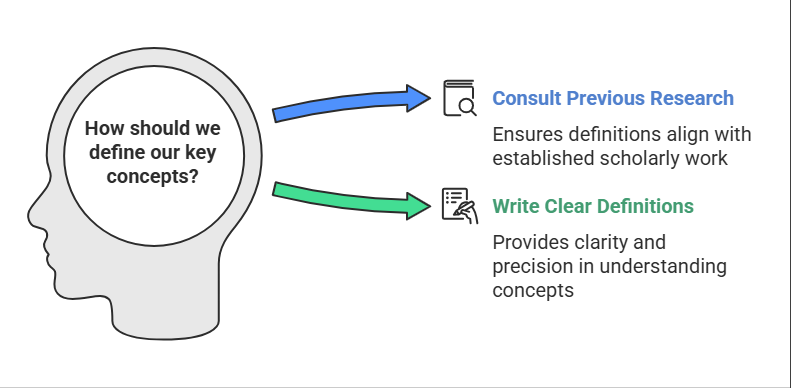

So, how do we define our concepts? This is the part of the measurement process known as conceptualization. The way that we define, or conceptualize, our concepts depends on how we plan to approach out research. We will begin with quantitative conceptualization and then discuss qualitative conceptualization.

In quantitative research, conceptualization involves writing out clear, concise definitions for our key concepts. Think about what comes to mind when you read the term masculinity. How do you know masculinity when you see it? Does it have something to do with men or with social norms? If so, perhaps we could define masculinity as the social norms that men are expected to follow. That seems like a reasonable start, and at this early stage of conceptualization, brainstorming about the images conjured up by concepts and playing around with possible definitions is appropriate. However, this is just the first step.

In addition, we should consult previous research and theory to understand the definitions that other scholars have already given for the concepts we are interested in. This doesn’t mean we must use their definitions, but understanding how concepts have been defined in the past will help us to compare our conceptualizations with other predominant conceptualizations. Understanding prior definitions of our key concepts will also help us decide whether we plan to challenge those conceptualizations or rely on them for our own work. Finally, working on conceptualization is likely to help in the process of refining your research question to one that is specific and clear in what it asks.

If we turn to the literature on masculinity, we will surely come across work by Michael Kimmel, one of the preeminent masculinity scholars in the United States. After consulting Kimmel’s prior work (2000; 2008), we might tweak our initial definition of masculinity. Rather than defining masculinity as “the social norms that men are expected to follow,” perhaps instead we’ll define it as “the social roles, behaviors, and meanings prescribed for men in any given society at any one time” (Kimmel & Aronson, 2004, p. 503). Our revised definition is more precise and complex because it goes beyond addressing one aspect of men’s lives (norms), and addresses three aspects: roles, behaviors, and meanings. It also implies that roles, behaviors, and meanings may vary across societies and over time. To be clear, we’ll also have to specify the particular society and time period we’re investigating as we conceptualize masculinity.

As you can see, conceptualization isn’t as simple as applying any random definition that we come up with to a term. The process may involve some initial brainstorming, but conceptualization goes beyond that. Once we’ve brainstormed about the images associated with a particular word, we should also consult prior work to understand how others define the term in question. After we’ve identified a clear definition that we’re happy with, we should make sure that every term used in our definition will make sense to others. Are there terms used within our definition that also need to be defined? If so, our conceptualization is not yet complete. Additionally, there is another aspect of conceptualization to consider known as concept dimensions. We’ll consider concept dimensions and additional words of caution in the next subsection.

Let’s Break it Down

Show

Conceptualization

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight.

Conceptualization means clearly defining what you mean by an idea or term, so everyone understands it the same way.

For example:

Let’s say your study is about marital satisfaction.

Before you measure it, you need to explain what you mean by “marital satisfaction.” Are you talking about how happy someone is in their marriage? How often they argue? How emotionally close do they feel?

So you look at past research and find that many scholars define marital satisfaction as:

“A person’s overall contentment with their marriage, including communication, emotional support, and shared goals.”

That definition becomes your conceptualization.

Dr. Christie Knight

Qualitative conceptualization

Conceptualization proceeds differently in qualitative research compared to quantitative research. Since qualitative researchers are interested in the understandings and experiences of their participants, it is less important for them to find one fixed definition for a concept before starting to interview or interact with participants. The researcher’s job is to accurately and completely represent how their participants understand a concept, not to test their own definition of that concept.

If you were conducting qualitative research on masculinity, you would likely consult previous literature like Kimmel’s work mentioned above. From your literature review, you may come up with a working definition for the terms you plan to use in your study, which can change over the course of the investigation. However, the definition that matters is the definition that your participants share during data collection. A working definition is merely a place to start, and researchers should take care not to think it is the only or best definition out there.

In qualitative inquiry, your participants are the experts on the concepts that arise during the research study. Your job as the researcher is to accurately and reliably collect and interpret their understanding of the concepts they describe while answering your questions. Conceptualization of qualitative concepts is likely to change over the course of qualitative inquiry, as you learn more information from your participants. Indeed, getting participants to comment on, extend, or challenge the definitions and understandings of other participants is a hallmark of qualitative research. This is the opposite of quantitative research, in which definitions must be completely set in stone before the inquiry can begin.

A word of caution about conceptualization

Whether you have chosen qualitative or quantitative methods, you should have a clear definition of the term masculinity and be sure that the terms we use in the definition are also clear… and then we’re done, right? Not so fast. You’ve likely met more than one man in your life, and you’ve probably noticed that they are not the same, even if they live in the same society during the same historical time period. This could mean there are dimensions of masculinity. In terms of social scientific measurement, concepts can be said to have multiple dimensions when there are multiple elements that make up a single concept. With respect to the term masculinity, dimensions could based on regional, age-based, or perhaps power-based definitions of the term. In any of these cases, the concept of masculinity would be considered to have multiple dimensions. While it is not required to spell out every possible dimension of the concepts you wish to measure, it may be important depending on the goals of your research. The point here is to be aware that some concepts have dimensions and to think about whether and when dimensions may be relevant to the concepts you intend to investigate.

Before we move on to the additional steps involved in the measurement process, it would be wise to remind ourselves not to take our definitions too seriously. Conceptualization must be open to revisions, even radical revisions, as scientific knowledge progresses. While I’ve suggested consulting prior scholarly definitions of our concepts, you should not assume that prior, scholarly definitions are more real than the definitions we create. Likewise, we should not think that our own made-up definitions are any more real than any other definition. It would also be wrong to assume that just because definitions exist for some concept that the concept itself exists beyond some abstract idea in our heads. Assuming that our abstract concepts exist in some concrete, tangible way is known as reification.

To better understand reification, take a moment to think about the concept of social structure. This concept is central to critical thinking. When social scientists talk about social structure, they are talking about an abstract concept. Social structures shape the way we exist in the world and the way we interact with one another, but they do not exist in any concrete or tangible way. A social structure isn’t the same thing as other sorts of structures, such as buildings or bridges. Sure, both types of structures are important to how we live our everyday lives, but one we can touch, and the other is just an idea that shapes our way of living.

Here’s another way of thinking about reification: Think about the term family. If you’re a family science student, how many times have you been asked to define this term in your class work so far? Has your definition changed at all as you’ve completed your studies? If you were interested in including the concept of family in your research study, it would be wise to consult prior theory and research to understand how the term has been conceptualized by others, but we should also question past conceptualizations. For example, think about how the definition of family was different 50 years ago. Researchers from that time conceptualized family using now outdated social norms, so the research of social scientists from 50 years ago was based on what we would consider a limited and problematic notion of family. Their definitions of family were as real to them as our definitions are to us today. If researchers never challenged the definitions of terms like family, our scientific knowledge would be filled with the prejudices and blind spots from years ago. It makes sense to come to some social agreement about what various concepts mean. Without that agreement, it would be difficult to navigate through everyday living, but we should not forget that we have assigned those definitions, so they are inherently imperfect and subject to change through critical inquiry.

Can I use AI for this?

Show

AI and Conceptual Clarity: Supportive Tool, Not Final Authority

AI can help develop conceptual definitions by summarizing theoretical perspectives, identifying key themes from academic literature, and synthesizing different viewpoints. AI is particularly useful in providing a broad overview of how a variable is generally understood within a field. But as always, there are precautions you need to take if you decide to use AI to help you formulate conceptual definitions. Flip through the following cards to better understand these precautions.

Dr. Christie Knight

Think about the “thing” variable you were asked to consider earlier in this page. What is your conceptualization of this variable at this time? Why do you define it the way you do? From experience? From reading? From something someone else said? Think about an alternative conceptualization that others could have for this variable. Keep these in mind (better yet, write them in your research notes) as you start to think about how you might measure those variables in your study design.

References

Babbie, E. (2010). The practice of social research (12th ed.). Wadsworth.

Kaplan, A. (1964). The conduct of inquiry: Methodology for behavioral science. Chandler Publishing Company.

Kimmel, M. (2000). The gendered society. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kimmel, M. (2008). Masculinity. In W. A. Darity Jr. (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social sciences (2nd ed., Vol. 5, p. 1–5). Macmillan Reference USA.

Kimmel, M., & Aronson, A. B. (2004). Men and masculinities: A-J. ABL-CLIO.

Milkie, M. A., & Warner, C. H. (2011). Classroom learning environments and the mental health of first grade children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 4–22.

Image attributions

measuring tape by unknown CC-0

human observer by geralt CC-0