Finding Literature

One of the drawbacks (or joys, depending on your perspective) of being a researcher in the 21st century is that we can do much of our work without ever leaving the comfort of our beds. This is certainly true of familiarizing yourself with the literature. Most libraries offer incredible online search options and access to important databases of academic journal articles. Be sure to check out the resources you have through your student status! Your professor might have ideas for where to start, but reaching out directly to a librarian is a severely under-used step. You might be amazed at what they know and what they can teach you – they’ve been trained specifically on the curation and retrieval of knowledge!

Whether you’re totally new to finding scholarly sources, or you’ve been doing this for a while, you’ll need to follow the same basic steps for retrieving information and sources to set up a research study. A literature search usually follows these steps:

- Building search queries

- Finding the right database

- Skimming the abstracts of articles

- Looking at authors and journal names

- Examining references

- Searching for meta-analyses and systematic reviews

After you’ve gathered helpful sources, you’ll begin the other processes we’ll discuss in this chapter, namely reading and using your sources (including citing them correctly!).

Step 1: Building a search query with keywords

What do you type when you are searching for something online? Are you a question-asker? Do you type in full sentences or just a few keywords? What you type into a database or search engine like Google is called a query; typing instructions into an AI Large-Language Model (LLM), like ChatGPT, is called a prompt, but it’s a similar idea. Well-constructed queries or prompts get you to the information you need faster, while unclear queries will force you to sift through dozens of irrelevant articles before you find the ones you want.

Searching with queries

First, let’s talk about querying a database or search engine. The words you use in your search query will determine the results you get. Unfortunately, different studies often use different words to mean the same thing. A study may describe its topic as substance abuse, rather than addiction. You might think “marriage therapy” but the study you actually want used “couples therapy.” Think of different keywords that are relevant to your topic area and write them all down. Often in social science research, there is a bit of jargon to learn in crafting your search queries. For example, if you wanted to learn about children who take on parental roles in families, you may need to include “parentification” as part of your search query. As undergraduate researchers, you are not expected to know these terms ahead of time. Instead, start with the keywords you already know. Once you read more about your topic, start including new keywords, many of which you’ll pick up from your early findings, that will return the most relevant search results for you. Experts in the specific topics you’re interested in (your professor for this or other classes, for example) may also have suggestions to help you get on the right track with the jargon you should expect to find.

Google, and some other search tools, is a “natural language” search engine, which means it tries to use its knowledge of how people to talk to better understand your query. Google’s academic database, Google Scholar, incorporates that same approach. However, other databases that are important for social science research—such as Academic Search Complete, PSYCinfo, and PubMed—will not return useful results if you ask a question, type a sentence, or use a phrase as your search query. Unlike Google Scholar, these databases are best used by typing in keywords. Instead of typing “the effects of cocaine addiction on the quality of parenting,” you might type in “cocaine AND parenting” or “addiction AND child development.” Note: you would not actually use the quotation marks in your search query for these examples.

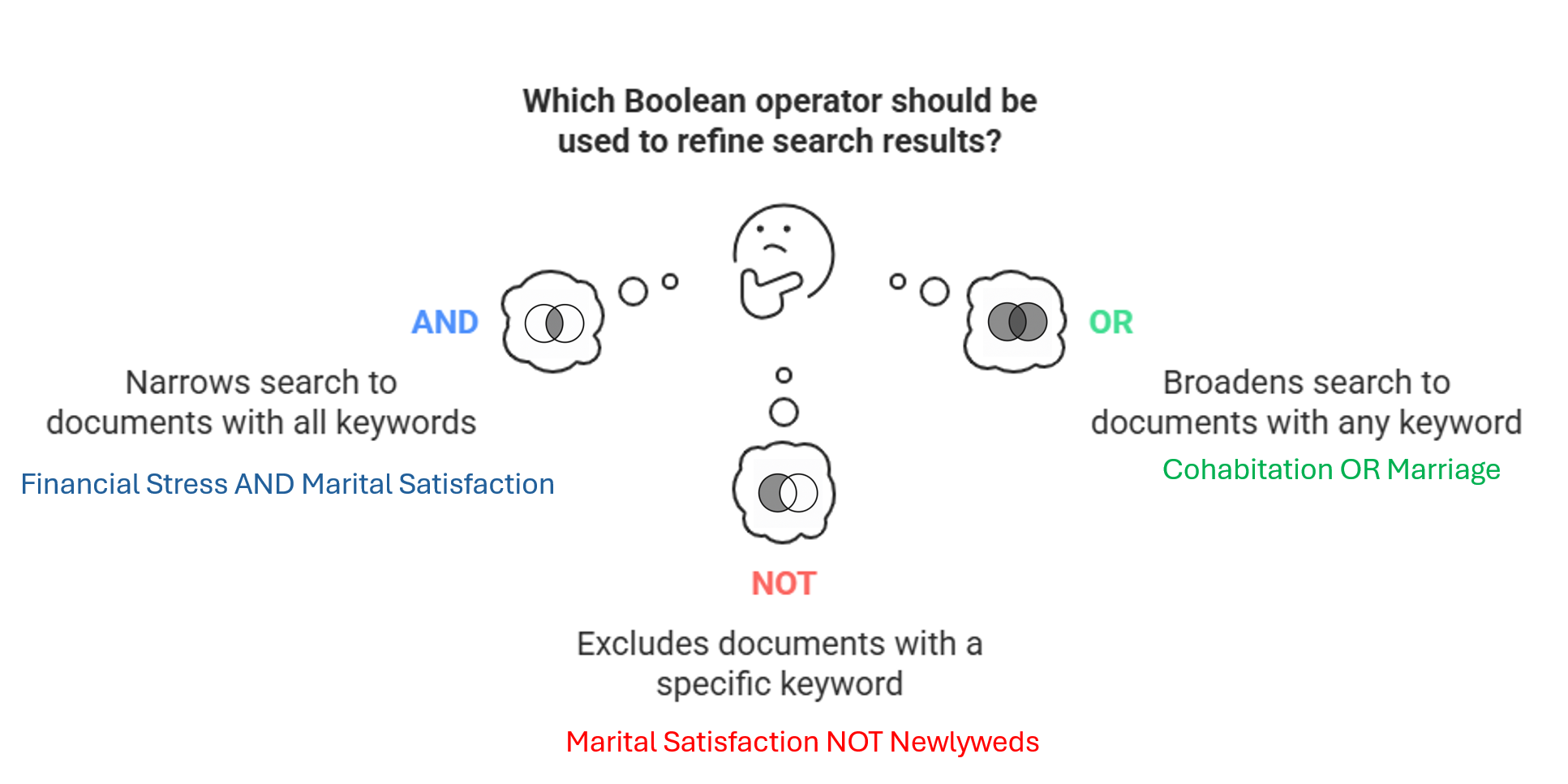

These operators (AND, OR, NOT) are part of what is called Boolean searching. Boolean searching works like a simple computer program. Your search query is made up of words connected by operators. Searching for “cocaine AND parenting” returns articles that mention both cocaine and parenting. There are lots of articles on cocaine and lots of articles on parenting, but fewer articles that discuss both topics together. In this way, the AND operator reduces the number of results you will get from your search query because both terms must be present. The NOT operator also reduces the number of results you get from your query. For example, perhaps you wanted to exclude issues related to pregnancy. Searching for “cocaine AND parenting NOT pregnancy” would exclude articles that mentioned pregnancy from your results. Conversely, the OR operator would increase the number of results you get from your query. For example, searching for “cocaine OR parenting” would return not only articles that mentioned both words but also those that mentioned only one of your two search terms. This relationship is visualized below.

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

Probably the most frustrating part about literature searching is looking at the number of search results for your query. How could anyone be expected to look at hundreds of thousands of articles on a topic? Don’t worry! You don’t have to read all those articles to know enough about your topic area to produce a good research study. A good search query should bring you to at least a few relevant articles to your topic, which is more than enough to get you started. However, an excellent search query can narrow down your results to a much smaller number of articles, all of which are specifically focused on your topic area. As you begin sifting through the results, you can also start narrowing in your queries, and with both processes happening you’ll likely find you can retrieve some very relevant sources without having to read a thousand papers.

Here are some tips for reducing the number of articles in your topic area:

- Use quotation marks to indicate exact phrases, like “mental health” or “substance abuse.”

- Search for your keywords in the ABSTRACT. A lot of your results may be from articles about irrelevant topics simply that mention your search term once. If your topic isn’t in the abstract, chances are the article isn’t relevant. You can be even more restrictive and search for your keywords in the TITLE. Academic databases provide these options in their advanced search tools.

- Use multiple keywords in the same query. Simply adding “addiction” onto a search for “substance abuse” will narrow down your results considerably.

- Use a SUBJECT heading like “substance abuse” to get results from authors who have tagged their articles as addressing the topic of substance abuse. Subject headings are likely to not have all the articles on a topic but are a good place to start.

- Narrow down the years of your search. Unless you are gathering historical information about a topic, you are unlikely to find articles older than 10-15 years to be very useful. They are less useful because they no longer tell you the current knowledge on a topic. All databases have options to narrow your results down by year.

- Talk to a librarian. They are professional knowledge-gatherers, and there is often a librarian assigned to your department. Their job is to help you find what you need to know.

Prompting AI

AI can also be a valuable resource for locating articles to help you begin gathering information on your topic. AI-powered tools or search engines can identify relevant academic papers, journal articles, and other credible sources. It can be useful for assistance in filtering results based on specific keywords and publication dates, or areas of focus. When used correctly, it can be a helpful resource and can save you time and effort in the initial stages of research.

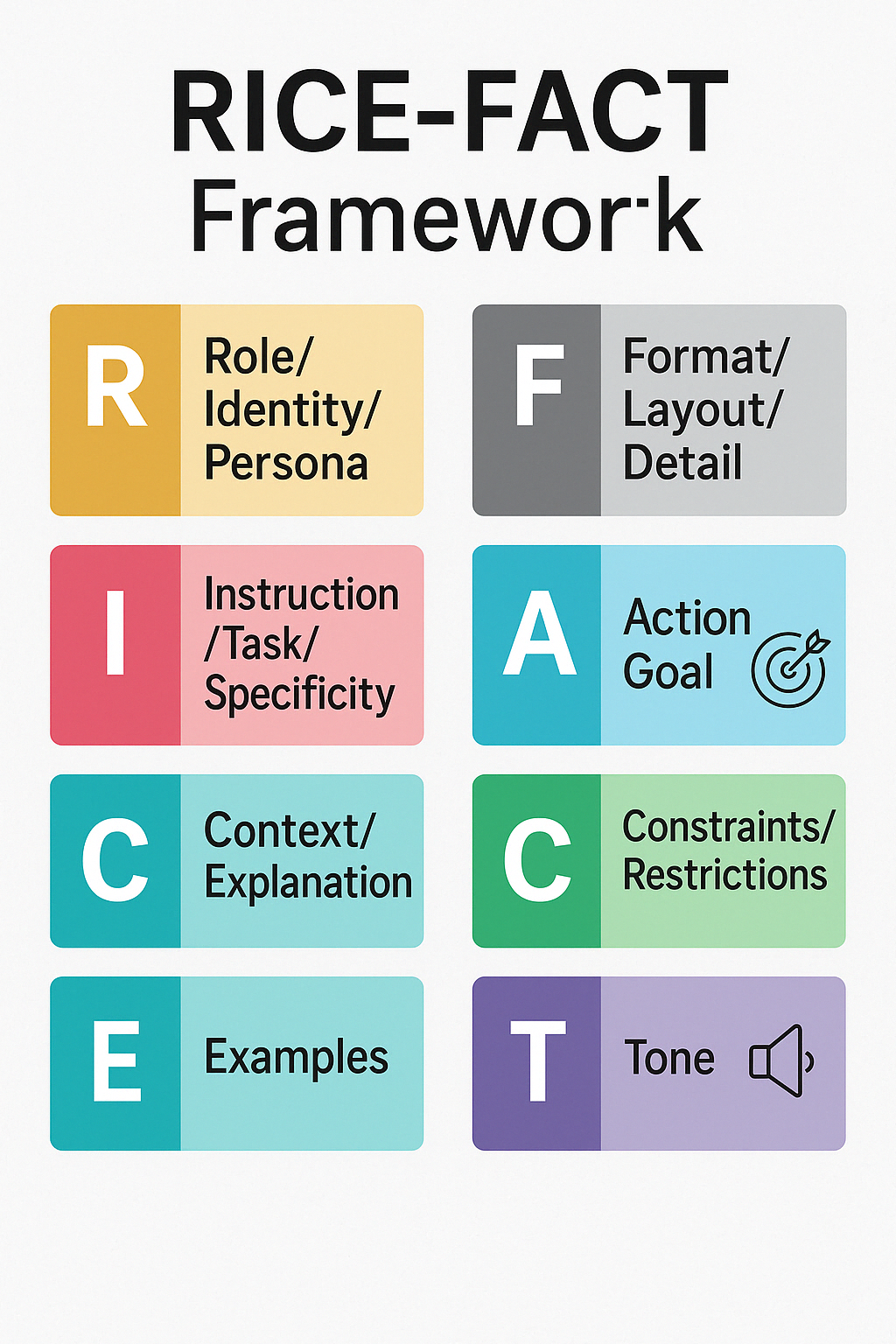

To prompt an AI model, you may find success by giving it a bit more detail than you would when querying a regular database. For example, telling it what role it should assume (an undergraduate student preparing for a research proposal), what you’re looking for and boundaries around what is acceptable (providing only peer-reviewed studies, for example), and even some examples of what would be correct can be helpful. This is not a book on AI-assisted research, so if you are interested in really developing your skills in this area, be sure to seek out the latest advice and research in this area to help you use these tools most effectively. If you’re just getting started, though, a model like RICE-FACT can help you engineer prompts that are most likely to return helpful information.

RICE-FACT: A Social Science Example

Show

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

“As a developmental psychologist, write a detailed summary explaining how adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) influence adolescent behavior and academic performance. The summary should be written in paragraph form, include examples from peer-reviewed studies, and focus on implications for school counselors. Avoid discussing biological/genetic influences and keep the tone professional but accessible to non-specialists.”

-

R: Developmental psychologist persona frames the AI’s approach.

-

I: Instruction to explain how ACEs influence adolescent behavior and academics.

-

C: Context focuses on the needs of school counselors.

-

E: Examples from peer-reviewed studies guide what kind of support is expected.

-

F: Paragraph format provides structure.

-

A: The goal is to write a summary for practical use.

-

C: The constraint to avoid biological/genetic factors narrows the scope.

-

T: Tone is professional but accessible to a lay audience.

By applying the RICE-FACT framework, we ensure the AI’s response is focused, relevant, and aligned with the task at hand—especially in the nuanced work of social science.

Dr. Christie Knight

Remember: if you use AI for any part of your research study, you have two important responsibilities. First, you MUST check all output. AI models are not actually thinking, they are simply following the prompts given to predict the most likely result. Because of this, AI models can and do hallucinate (make up fake data, sources, or results) or they may misrepresent a source. It is your responsibility as a student and scholar to read any source you cite in a paper or project; if an AI model gives you a source, you still must read it yourself before you can ethically use it. Secondly, you should disclosure your use of the AI model, including what you did and how you evaluated it, in your assignment. Some classes, professors, and universities completely prohibit the use of AI in assignments. Be sure to read your syllabus closely (and check with your professor if you’re still unsure) before using AI for an assignment, and if it is allowed, also carefully read the disclosure requirements. If your syllabus doesn’t state exactly how to disclose, a good model to follow is the MInE example (as described by Overono & Ditta [2024]): state the Model that was used (ChatGPT 4.o for example), the Input (what prompt you used and how you interacted with the model), and the Evaluation you performed on the results, both how you checked the output (read the sources it found yourself, for example) and your own evaluation of the ethics of how you used the model.

Step 2: Finding the right database

There are a number of databases in which you might find important and helpful resources for your research. For example, you’ve probably seen results on Google Scholar, Academic Search Complete, PubMed, and others. Each has distinct advantages and disadvantages, and you might want to talk to your professor about their thoughts on the best database for your needs.

Because Google Scholar is a natural language search engine, you are more likely to get what you want without having to fuss with wording. It can be linked via Library Links to your university login, allowing you to access journal articles with one click on the Google Scholar page. Google Scholar also allows you to save articles in folders and provides a (somewhat correct) APA citation for each article. Google Scholar will automatically display not only journal articles, but also books, government and foundation reports, and gray literature, so you need to make sure that the source you are using is reputable. Look for the advanced search feature to narrow down your results further.

Academic Search Complete is likely available through your school’s library, usually under page titled databases. It is similar to Google Scholar in its breadth, as it contains a number of smaller databases from a variety of social science disciplines. You have to use Boolean searching techniques, and there are a number of advanced search features to further narrow down your results.

PubMed is interesting because it indexes articles related to medical science, as well as other health-related research. It houses research that has been completed with funding support from the National Institutes of Health in the United States. You might think to yourself “but my research isn’t directly health-related,” but don’t discount PubMed as an option for you. Many social scientists have ties to the National Institutes of Health at some point in their training and careers, and this means that their work can often be found on this database! If you do find a source on PubMed, be sure to examine it to see what journal it was published in, then do all the same analysis of that journal that you would with any source you find (and when you go to make the reference for the source, use the journal information you found to format that correctly).

Additionally, many universities have their own database search through their library systems; these have been curated to be helpful to your needs as a student and scholar, plus they have the added bonus of having support (the library’s staff) available directly to you as a student! Take advantage of those resources whenever you can. These often combine other databases into one convenient search, so it can be one of the most helpful places to search!

Step 3: Skimming abstracts and obtaining full texts

Once you’ve settled on your search query and database, you should start to see articles that might be relevant to your topic. Rather than read every article, skim through the abstract to judge whether this article is relevant to your specific topic – you might be surprised how often searching “parent” or “marriage” can actually turn up results in computer science if you’ve not narrowed it down very well! If you feel the article does in fact fit your topic and will be interesting or helpful to you, make sure to download the full text PDF to your computer so you can read it later. Part of the tuition and fees your university charges you goes to paying major publishers of academic journals for the privilege of accessing their articles. Because access fees are incredibly costly, your school likely does not pay for access to all the journals in the world. While you are in school, you should never have to pay for access to an academic journal article. Instead, if your school does not subscribe to a journal you need to read, try using inter-library loan to get the article. On your university library’s homepage, there is likely a link to inter-library loan. Just enter the information for your article (e.g. author, publication year, title), and a librarian will work with librarians at other schools to get you the PDF of the article that you need. After you leave school, getting a PDF of an article becomes more challenging. However, you can always ask an author for a copy of their article (look for their email address under the “author information” part of the article). They will usually be happy to hear someone is interested in reading and using their work, and they don’t get paid for their papers anyway so you’re not asking them to give up any financial incentives or anything. Finally, look to see if the paper you’ve found is on PubMed or another repository of publicly-funded research; as mentioned above, you might be surprised at how many studies relevant to non-medical subjects are on Pubmed!

What do you do with all of those PDFs? You could put them into folders on cloud storage drive, arranged by topic, or save them to a flashdrive with an organization pattern than makes sense to you. For those who are more ambitious (or konw you’ll be writing a lot of papers on a topic), you may want to use a reference manager. An excellent one to start with is Zotero, though you can also explore others like Mendeley, EndNote, or RefWorks. References managers keep papers organized, allow you to take notes or attach other helpful documents; later in your writing process, they can also generate and format your citations and references.

No matter how you store the full-texts you find, at the very least, take notes on each article you read and think about how it might be of use in your study.

Step 4: Searching for author and journal names

As you scroll through the list of articles in your search results, you should begin to notice that certain authors appear more than once. If you find an author that has written multiple articles on your topic, consider searching the AUTHOR field for that particular author. You can also search the web for that author’s Curriculum Vitae or CV (an academic resume) that will list their publications. Many authors maintain personal websites or host their CV on their university department’s webpage. Just type in their name and “CV” into a search engine.

You can also narrow down your results by journal name if you find a journal that seems particularly relevant to your area. As you are scrolling, you might notice that many of the articles you’ve skimmed come from the same journals. Searching with that journal name in the JOURNAL field will allow you to narrow down your results to just that journal. For example, if you are searching for articles related to parenting and internal processes of families, you might find Family Process helpful. You can also navigate to the journal’s webpage and browse the abstracts of the latest issues.

Step 5: Examining references

As you begin to read your articles, you’ll notice that the authors cite additional articles that are likely relevant to your topic area. Using their lists of resources to then find papers helpful to you is called archival searching. Unfortunately, this process will only allow you to see relevant articles from before the publication date. That is, the reference section of an article from 2014 will only have references from pre-2014. If you’d rather see what other sources have cited the study you’re reading since it was published, you can use Google Scholar’s “cited by” feature to do a future-looking archival search. Look up an article on Google Scholar and click the “cited by” link. This is a list of all the articles that cite the article you just read. Google Scholar even allows you to search within the “cited by” articles to narrow down ones that are most relevant to your topic area. For a brief discussion about archival searching check out Hammond & Brown (2008).

Step 6: Searching for systematic reviews and other sources

Another way to bolster your literature searching is to look for articles that synthesize the results of other articles. Systematic reviews provide a summary of the existing literature on a topic. If you find one on your topic, you will be able to read one person’s summary of the literature and go deeper by reading their references (though remember, they’ll only have what was published before them, so you might still need to search out the newest information if it’s been a few years). Similarly, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses have long reference lists that are useful for finding additional sources on a topic. They use data from each article to run their own quantitative or qualitative data analysis. In this way, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses provide a more comprehensive overview of a topic. To find these kinds of articles, include the term “meta-analysis,” “meta-synthesis,” or “systematic review” to your search terms. Another way to find systematic reviews is through the Cochrane Collaboration or Campbell Collaboration. These institutions are dedicated to producing systematic reviews for the purposes of evidence-based practice.

Putting it all together

Familiarizing yourself with research that has already been conducted on your topic is one of the first stages of conducting a research project and is crucial for coming up with a good research design. You do not have to go it alone, though – look for resources on your campus (or online through your school’s website) to help you, including library staff but also writing centers, tutoring services, and academic success staff. Ask around to see what’s there to help you!

References

- Hammond, C. C. & Brown, S. W. (2008, May 14). Citation searching: Searching smarter & find more. Computers in libraries. Retrieved from: http://www.infotoday.com/cilmag/may08/Hammond_Brown.shtml

- Overono, A. L., & Ditta, A. S. (2024). The use of AI disclosure statements in teaching: Developing skills for psychologist of the future. Teaching of Psychology, 52(3), 273-278. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00986283241275664