What is Research Design?

Before making decisions about study design, it is important to ask yourself a few critical questions:

Research Aims

- What is the overall goal of your research: to explore, describe, explain, or predict?

- What knowledge paradigm does your research question best align with?

- Does your question focus on cause-and-effect relationships, or is it more focused on finding meaningful themes and exploring them in depth?

Unique Contributions

- What questions do you want to answer that have not been addressed by prior studies?

- What research methods have been used in other studies on your chosen topic? What are their strengths and limitations?

- How will your study build upon other studies (address new questions, apply a new methodological approach, think about the topic from a fresh angle)?

Practical Considerations

- How much time and money do you have to conduct the study?

- Do you have special skills, knowledge, or experience with certain approaches to research?

- Do you have other researchers you can collaborate with who have complementary skills or knowledge?

After considering your research aims, the unique contributions your study will make, and practical considerations like time, money, and expertise, you will need to think about what your study will actually look like. Who will we analyze? How will we recruit participants? How will we collect data, and how will we measure the variables we are interested in studying? What ethical considerations should we make (we have already learned about research ethics, but we will continue to consider it when discussing each type of research design)? How will we store and analyze our data?

These decisions determine the quality of your research, so they’re important to keep in mind when designing a study. These principles can also help you evaluate the quality of other studies you read about. When reading or evaluating any research study it’s worth asking yourself how you feel about the sampling, measurement, and ethics of the study. However, it’s important to remember that no study is perfect – researchers must consider different priorities and make design decisions that align with the overall purpose of the study. Every study has limitations, or design aspects that aren’t perfect. These design decisions can be made due to practical reasons such as cost, time, or convenience, or because of other priorities like treating participants ethically or using measurement tools that are widely known and used by other researchers. However, each study also has its strengths which allow it to uniquely contribute to the field of research. When many imperfect studies come together, each with its own strengths and limitations, we learn much more than we could from any single study.

It is important to remember that there is almost never one single “right” answer in research design. Different researchers, with different philosophies and ideas, will approach the same questions in very different ways based on their own schools of thought – remember learning about knowledge paradigms and ways of knowing in Chapter 1? Each researcher must make their own decisions, justify the decisions to themselves, and then defend the decisions to others. One of the great features of science is that over time some ideas will hold up and others will fall away as those who engage with the ideas find what’s useful and filter out what’s not.

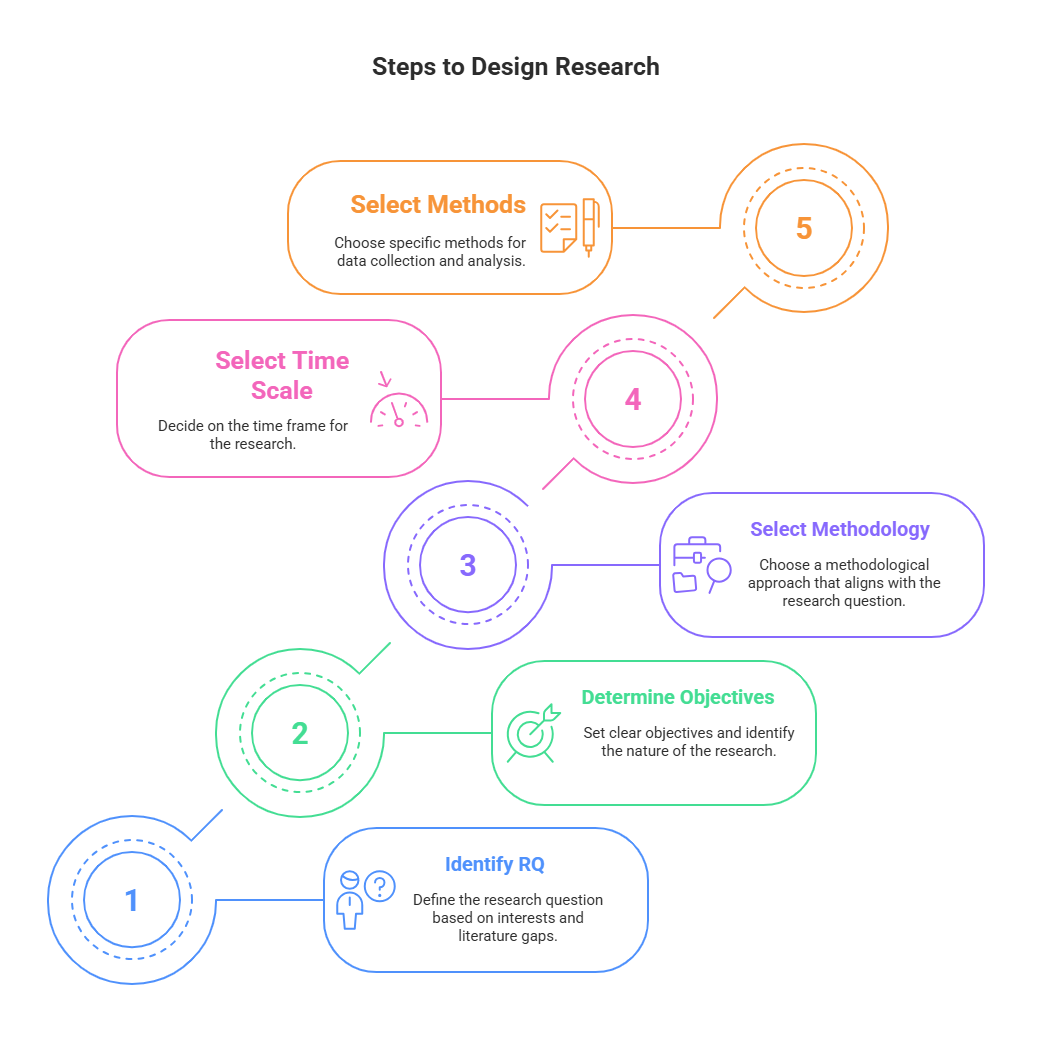

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

Research Design Decisions

Research Methodology

Research methodology is the big-picture plan behind how a study is done. It’s based on a particular way of thinking about the world, like whether we believe there’s one “truth” to discover or many different perspectives. This approach helps guide all the decisions in a study—like what kind of data to collect and how to make sense of it. For example, if a researcher wants to understand people’s personal experiences, they might choose interviews and analyze the stories people share. If they want to test how one thing affects another, they might run an experiment and use statistics. The methodology keeps the study focused and consistent from start to finish.

Ethical Considerations

Ethics are all about making sure research is done in a way that’s fair and respectful to the people involved. If a study includes human participants, it usually needs approval from a group called an Institutional Review Board (IRB), which checks to see if the study protects people’s rights and safety. But getting IRB approval isn’t enough by itself—researchers also need to use good judgment. For example, they should clearly explain what the study is about, get informed consent, protect people’s identities, and avoid doing anything that could cause harm. Ethical research is about being responsible and treating people with care.

Unit of Analysis

The unit of analysis is the “thing” you’re studying in your research. It could be a single person, a group, an organization, a city, or even an event. For example, if you’re studying how students cope with stress, your unit of analysis is individual students. If you’re comparing how different schools handle mental health services, your unit of analysis might be schools instead. Choosing the right unit of analysis is important because it affects how you collect and analyze your data. It also helps make sure your research question matches what you’re actually studying.

Timescale

The timescale of a study refers to how often data are collected over time. A cross-sectional study collects data at just one point in time. It’s like taking a snapshot—it gives you a quick look at what’s happening right now. These studies are usually faster and cheaper to do, but they can’t show how things change over time.

In contrast, a longitudinal study collects data from the same participants over a longer period, like checking in every few months or years. This approach is more like a video than a snapshot—it lets researchers track changes and look at cause-and-effect relationships. However, longitudinal studies can take a lot more time and resources.

Choosing between cross-sectional and longitudinal designs depends on your research question. If you want to know what’s happening now, go with cross-sectional. If you’re trying to understand change or development, longitudinal is the better choice.

Timeline and Budget

Planning a research study also means figuring out how long it will take and how much it will cost. A timeline breaks the project into steps—like background research, getting approval, collecting data, analyzing results, and writing it all up. A budget lists all the expected costs, such as paying participants, buying software, printing surveys, and covering travel expenses. Even small studies benefit from a basic plan. It helps researchers stay organized, avoid surprises, and make sure they can actually finish what they start.

Research Methods

Research methods are the specific tools and techniques researchers use to carry out their study. Once a research question and overall approach (methodology) are decided, methods help put that plan into action. This includes figuring out who to study (sampling), what to measure and how to measure it (variables and measurement), how to gather the information (data collection methods), and how to make sense of the results (data analysis techniques). Research methods include the following:

Sampling

A sampling strategy is how researchers choose the people (or things) they want to study. Ideally, the sample should represent the bigger group they’re interested in—like choosing college students from different majors if studying student stress. Sometimes researchers use random sampling, while other times they use whoever is available (called convenience sampling). The method they choose depends on their goals and resources. What matters most is being clear about who was included and why, so others can understand how well the findings might apply to the larger population.

Variables and Measurement

Variables are the things researchers are trying to study—like stress levels, test scores, or physical activity. Measurement is how they figure out the amount or presence of these variables. A good measurement tool gives results that are both accurate (measuring what it’s supposed to) and reliable (producing similar results each time). Sometimes, measurements are objective (like heart rate), and sometimes they’re based on opinions or feelings (like survey answers). It’s important that researchers pick tools that match their research goals and make sure they use them correctly, so the data they collect is solid and trustworthy.

Data Collection

Data collection is how researchers gather the information they need. Different methods are used depending on the kind of question being asked. For example, interviews are great for deep, personal insights; surveys work well for reaching lots of people quickly; observations are useful for watching behaviors in real settings; and biological measures (like blood pressure or cortisol levels) are used when researchers need physical data. Each method has its pros and cons, and choosing the right one helps researchers get the kind of data that best fits their study.

Data Analysis

Data analysis is how researchers make sense of the information they’ve collected. In studies with numbers (quantitative), they might use statistics to look for patterns, compare groups, or test whether something caused a change. In studies with words and experiences (qualitative), they might read through interview transcripts and look for common themes or ideas. Sometimes, researchers use a mix of both. The goal is to find meaning in the data and answer the research question in a clear and honest way.

Different research questions call for different combinations of methods. For example, a psychology study might use surveys and statistical tests, while a public health project might include interviews and observational data. Good research methods are carefully chosen to match the goals of the study and ensure the results are trustworthy, meaningful, and clear. We’ll discuss these issues in detail throughout the rest of this book!