Who, What, When, Where, and How?

When designing a study, it’s important to understand what or who you’re studying, when you’re measuring it (and how often), and where you’ll be collecting your data. These decisions will determine other aspects of your study design, such as your sample and method of data collection.

Unit of Analysis

The unit of analysis is a key part of any research study—it tells us what or who we’re studying. Are we looking at individuals, like one person’s experiences or behaviors? Or are we focused on groups, like families, schools, communities, or entire countries? Getting clear about the unit of analysis helps make sure your research question, data, and analysis all line up.

Sometimes the unit of analysis is obvious. For example, if you’re studying how students cope with stress, you’re probably focusing on individual students. But other times it’s more complicated. For example, if you’re comparing how different schools support student mental health, then your unit of analysis isn’t the student—it’s the school.

Why does this matter? Because the unit of analysis affects how you collect and interpret your data. If your unit is the individual but you accidentally collect data at the group level—or vice versa—you might draw the wrong conclusions.

Here’s an example from family science: let’s say you want to study how conflict affects marital satisfaction. If your unit of analysis is the individual, you might look at each partner’s perspective separately. But if your unit is the couple, you’d need to combine or compare both partners’ responses to make conclusions about the relationship as a whole. Your findings and interpretation could be very different depending on that choice.

Time Scale

Time is an important aspect of research. When are we measuring what we’re measuring, how often will we measure it, and are measuring something happening right (prospective) or something that happened in the past (retrospective)? Two common types of research are cross-sectional and longitudinal. Cross-sectional studies are studies that take place at one point in time only. Longitudinal studies are those that take place at multiple time points. This might be by getting data from the same respondents at multiple times (before and after an event, for example, or once a month for a year), which is called a panel study, or it could be by getting data from different respondents but at multiple times (repeating a survey every year with different samples each time, for example), which is called a repeated cross-section.

The choice of time matters greatly in research. To understand why, let’s look at an example that is familiar to many family scientists: marital satisfaction. This has obviously been an important topic to family scientists for a long time. Many early studies of marital satisfaction showed a pattern – satisfaction was high in early years, declined over time until about a decade in, stayed low for a few years, then started to increase again. This curvilinear relationship came to be known as the U-shaped curve and was an accepted fact by many marriage researchers. In fact, you’ve probably read about this now-famous U-shaped curve in your introductory family science textbooks. Unfortunately, though, that shape is probably not right – rather, it’s an effect of the way time was handled in many of those early research studies on the topic because they were using cross-sectional data.

Picture, for a moment, how you might conduct a cross-sectional version of a study looking at the association between marital satisfaction and marital duration. You might take one big sample at one time of people of lots of marital durations. In this sample, you’d have newlyweds all the way to people celebrating their 40th anniversaries all reporting on their marital satisfaction at this one same point in time. In this case, if you then plotted the scores against time, you might, indeed, see a U-shaped curve. Those who haven’t been married very long and those who have been married the longest likely have higher scores than those in the middle ranges. However, does this mean that marital satisfaction actually changes each year in this same pattern over the time a couple is married? Likely not! We’re just getting a snapshot of what different people, at different lengths of marriage, are experiencing.

Instead, if we tracked individual marriages over time and assessed their satisfaction at year 1, then year 2, then year 5, 15, and 25, we’d actually be able to see how the satisfaction in a specific relationship shifts over time. That’s a longitudinal panel study – same people measured over and over. Some researchers have actually done this, and the results look very different from the U-shaped curve that has been popularized.

In 2001, VanLaningham and colleagues took this question head-on using the Marital Instability over the Life Course study, a panel study with measurements taken in 1980, 1983, 1988, 1992, and 1997. First, they treated their data as cross-sectional by using only the very first wave from 1980. With those data, they did indeed find a U-shaped curve, much as many studies before them had done. However, when they brought in the additional waves and treated it longitudinally, a very different picture emerged: it was still curvilinear (meaning the line wasn’t totally straight), but instead of a drop after the first years and then rising after a low point in the middle years, satisfaction dropped after the first years, then flattened out in the middle years and dropped some more in the later years!

So what happened? The best explanation of the U-curve in cross-sectional studies tends to be that there was a “cohort effect” emerging, that is, the people who were representing the marriages at different durations in the cross-sectional studies were parts of different cohorts – those who were representing the latest marriages in 1980, for example, were by definition older and had been married in times when marriage had different meanings and expectations than those who were married for fewer years. The cross-sectional data were picking up on changes of tracking changes to the groups who were married, rather than changings within marriage among the same people.

It’s not all bleak news for marriage though! Some even newer data suggests that we should apply some additional techniques to our longitudinal data to further look at individual differences (Proulx et al., 2017), and there are of course many experiences and characteristics that also play into marital quality and satisfaction over time. This example shows, however, that we need to be careful to use the right methods for the right questions, and not over-interpret what’s happening in cross-sectional data if longitudinal data might give us a different picture.

Prospective vs. Retrospective Research

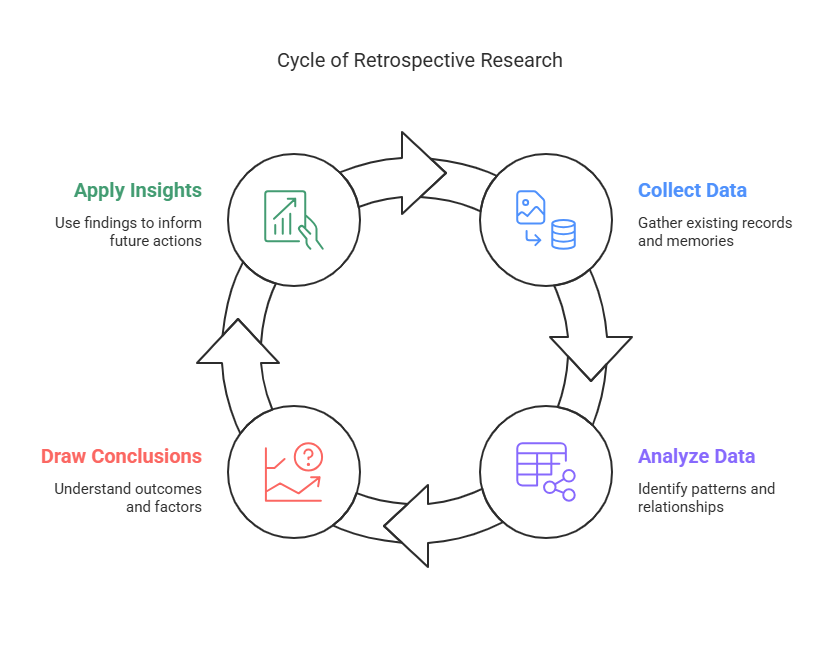

Another aspect of time that is important to consider is whether you’ll be collecting prospective or retrospective data. That is, are you collecting data as it is happening (prospective) or after it’s happened (retrospective)? A lot of studies are, by necessity, retrospective. Retrospective research is a research method that examines past events to gain a deeper understanding of current outcomes. It utilizes existing data, records, or participants’ memories to explore the relationships between factors and outcomes that have already occurred. If you’re being asked to report on your childhood experiences as a young adult, you’re giving a retrospective account of the experiences. Sometimes, the experience may not be particularly long ago but can still be retrospective – asking a couple to recount how they met, even if that was last year, is still retrospective. You can probably already guess what the risks are with retrospective data: memory! Human memories are inherently fallible. If you’re asking someone to report on something in specific detail (like how many hours they spent vacuuming or doing other household chores last week, as an example), you may or may not get the story of exactly how things went.

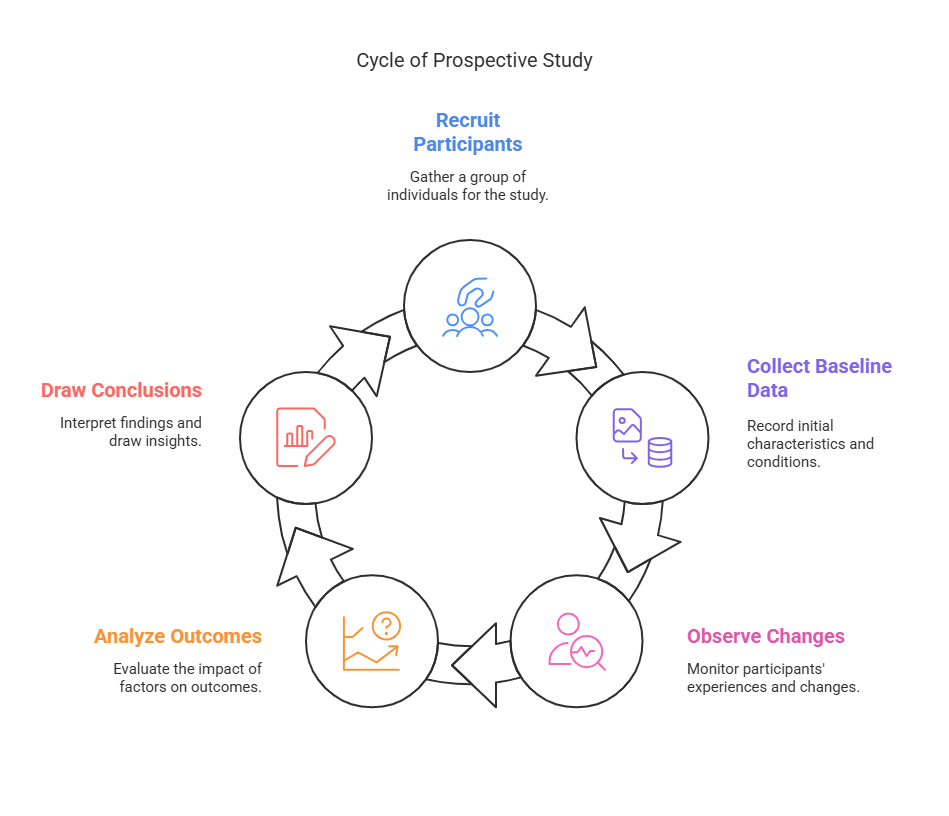

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

In contrast, measuring things as they happen is prospective. Sometimes, this actually looks like data being collected during an experience (like in an experience-sampling study, where someone is asked to enter data onto a device – like an app on their phone – at planned or random times throughout the day), or it can also mean collecting data throughout a longer period that then, when everything is said and done, happens to contain the experience of interest (like a study that starts on children in first grade and collects measures of their family life and mental health throughout their school years – at the end of high school, the researchers could look back and see which children experienced parental divorce and when, then examine how their mental health changed at those times). If we take our example above of housework, asking someone to record what they’re doing for each 15-minute period of a day for two days (this is a version of a time diary) will give very different data than the retrospective survey above. In fact, this exact comparison, of survey to time diary, produced some very important and impactful findings regarding household labor distribution across the transition to parenthood in a 2015 study called “The Production of Inequality: The Gender Division of Labor Across the Transition to Parenthood.”

The choice of prospective vs. retrospective data is sometimes made for a researcher – if an event has already taken place, they can’t go back in time to set up the study beforehand! However, if there is an option to use or collect data as something is happening, a researcher should balance what may be gained vs. what resources would be required. Sometimes retrospective data is actually completely sufficient for a study’s purposes!

Environment

Once you’ve decided who and what you’re analyzing and when, you must consider where your study will take place, also known as the research environment. “Environment” could mean the physical space in which the research is done (do you meet your interview participants at their home? A coffee shop? Your on-campus lab?) or even an online space, if you’re collecting data via an online survey or remote interview. Online studies are only growing, of course, but special considerations must be made for online research, such as the inability to explain the informed consent to participants – it must be clear enough for them to be able to read and understand it themselves. If your research will take place in a physical setting, being thoughtful about access (this relates to the ethical principle of justice), comfort, power, and convenience will be important. Consider if a setting is realistic, but also how controllable it is. If you need a lot of control for a study (you need each person’s experience to be exactly the same, like in an experiment), then having the study take place in a lab might be important. If you don’t care as much about control, or have a way to control the setting elsewhere, having a study team actually go to a participants’ home may be the most accessible method. Safety must also be considered though – there’s a lot that goes into research decisions!

Research Methods

Now that you know who and what you’re studying and when and where your study will take place, it’s time to determine how your study will take place, including the specific techniques and procedures you will use to carry out your study. These include decisions about sampling, variables and measurement, data collection, and data analysis. Research methods should align with your research question, objectives, and methodology. Some researchers consider things like the unit of analysis, time scale, and methodology part of their research design. However, in this book we will use the term research methods to refer to the following:

Sampling

A sampling strategy is how researchers recruit participants for their study. Ideally, the sample should represent the bigger group they’re interested in—like choosing college students from different majors if studying student stress. Sometimes researchers use random sampling, while other times they use whoever is available (called convenience sampling). The method they choose depends on their goals and resources. What matters most is being clear about who was included and why, so others can understand how well the findings might apply to the larger population.

Variables and Measurement

Variables are the things researchers are trying to study—like stress levels, test scores, or physical activity. Measurement is how they figure out the amount or presence of these variables. A good measurement tool gives results that are both accurate (measuring what it’s supposed to) and reliable (producing similar results each time). Sometimes, measurements are objective (like heart rate), and sometimes they’re based on opinions or feelings (like survey answers). It’s important that researchers pick tools that match their research goals and make sure they use them correctly, so the data they collect is solid and trustworthy.

Data Collection

Data collection is how researchers gather the information they need. Different methods are used depending on the kind of question being asked. For example, interviews are great for deep, personal insights; surveys work well for reaching lots of people quickly; observations are useful for watching behaviors in real settings; and biological measures (like blood pressure or cortisol levels) are used when researchers need physical data. Each method has its pros and cons, and choosing the right one helps researchers get the kind of data that best fits their study.

Data Analysis

Data analysis is how researchers make sense of the information they’ve collected. In studies with numbers (quantitative), they might use statistics to look for patterns, compare groups, or test whether something caused a change. In studies with words and experiences (qualitative), they might read through interview transcripts and look for common themes or ideas. Sometimes, researchers use a mix of both. The goal is to find meaning in the data and answer the research question in a clear and honest wayReferences

References

Proulx, C. M., Ermer, A. E., & Kanter, J. B. (2017). Group-based trajectory modeling of marital quality: A critical review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9, 307-327. 10.1111/jftr.12201

VanLaningham, J., Johnson, D. R., & Amato, P. (2001). Marital happiness, marital duration, and the u-shaped curve: Evidence from a five-wave panel study. Social Forces, 78(4), 1313-1341.