Informed Consent

As should be clear by now, conducting research on humans presents a number of unique ethical considerations. Human research subjects must be given the opportunity to consent to their participation, after being fully informed of the study’s risks, benefits, and purpose. Further, subjects’ identities and the information they share should be protected by researchers. Of course, the definitions of consent and identity protection may vary by individual researcher, institution, or academic discipline. In this section, we’ll look at a few specific topics that individual researchers and social workers must consider before conducting research with human subjects.

All social work research projects involve the voluntary participation of all human subjects. In other words, we cannot force anyone to participate in our research without their knowledge and consent, unlike the experiment in Truman Show. Researchers must therefore design procedures to obtain subjects’ informed consent to participate in their research. Informed consent is defined as a subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in research based on a full understanding of the research and of the possible risks and benefits involved. Although it sounds simple, ensuring that one has actually obtained informed consent is a much more complex process than you might initially presume.

The first requirement to obtain informed consent is that participants may neither waive nor even appear to waive any of their legal rights. In addition, if something were to go wrong during their participation in research, participants cannot release the researcher, the researcher’s sponsor, or any institution from any legal liability (USDHHS, 2009). Unlike biomedical research, for example, social science research does not typically involve asking subjects to place themselves at risk of physical harm. Because of this, social researchers often do not have to worry about potential liability, however their research may involve other types of risks.

For example, what if a social researcher fails to sufficiently conceal the identity of a subject who admits to participating in a local swinger’s club? In this case, a violation of confidentiality may negatively affect the participant’s social standing, marriage, custody rights, or employment. Social research may also involve asking about intimately personal topics, such as trauma or suicide that may be difficult for participants to discuss. Participants may re-experience traumatic events and symptoms when they participate in your study. Even after fully informing the participants of all risks before they consent to the research process, there is the possibility of raising difficult topics that prove overwhelming for participants. In cases like these, it is important for a social researcher to have a plan to provide supports, such as referrals to community counseling or even calling the police if the participant is a danger to themselves or others.

It is vital that social researchers craft their consent forms to fully explain their mandatory reporting duties and ensure that subjects understand the terms before participating. Researchers should also emphasize to participants that they can stop the research process at any time or decide to withdraw from the research study for any reason. Importantly, it is not the job of the social researcher to act as a clinician to the participant whether or not the research is themselves a trained therapist. While a supportive role is certainly appropriate for someone experiencing a mental health crisis, social workers and other therapists must ethically avoid dual roles. Referring a participant in crisis to other mental health professionals who may be better able to help them is preferred. If the researcher is themselves not a clinician, it is even more important that they have a plan in place for referrals and supportive measures if needed.

In addition to legal issues, most IRBs are also concerned with details of the research, including: the purpose of the study, possible benefits of participation, and, most importantly, potential risks of participation. Further, researchers must describe how they will protect subjects’ identities, explain all details regarding data collection and storage, and provide contact details for additional information about the study and the subjects’ rights. All of this information is typically shared in an informed consent form that researchers provide to subjects. In some cases, subjects are asked to sign the consent form indicating they have read it and fully understand its contents. In other cases, subjects are simply provided a copy of the consent form and researchers are responsible for making sure subjects have read and understand the form before proceeding with any kind of data collection. The IRB application will specify if a signature is required or not.

In this interactive activity, you will use an H5P hotspot tool to explore the essential components of a consent form. The hotspot is designed as a Consent Form Checklist, where each checkmark represents a key element that should be included in an ethically sound consent form. As you select each checkmark, you will gain insight into its purpose, why it is necessary, and how it protects both researchers and participants. By the end of this activity, you will have a clearer understanding of what makes a well-constructed consent form. Start by clicking on the checklist items and see what essential details you uncover!

* The image for the activity was created using ChatGPT; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight.

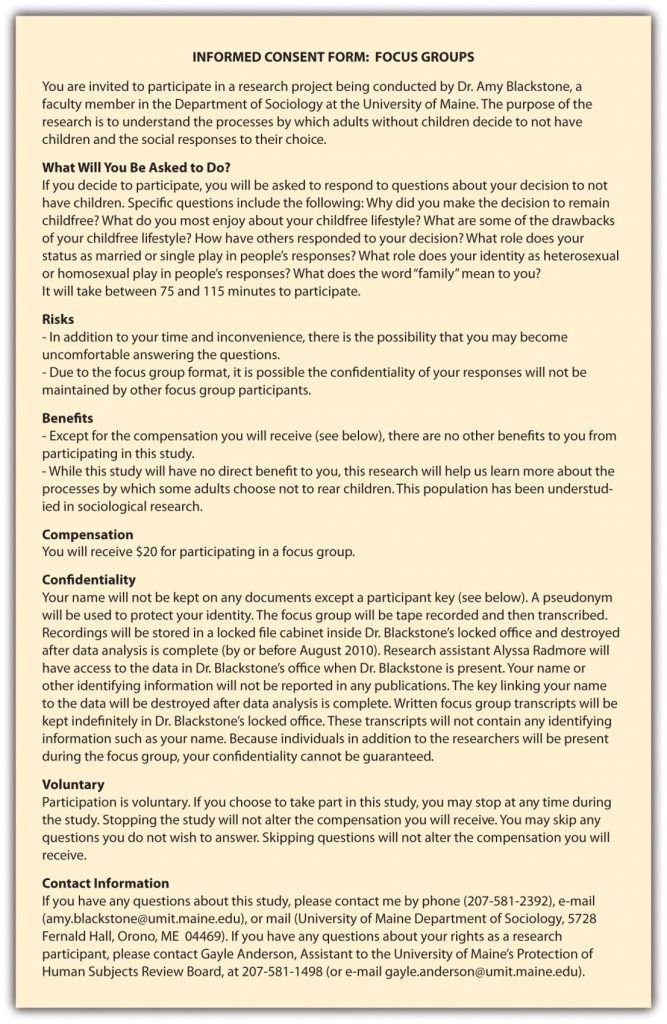

The image below showcases a sample informed consent form taken from a research project on child-free adults. Note that this consent form describes a risk that may be unique to the particular method of data collection being employed: focus groups.

When preparing to obtain informed consent, it is important to consider that not all potential research subjects are considered equally competent or legally allowed to consent to participate in research. Subjects from vulnerable populations may be at risk of experiencing undue influence or coercion. The rules for consent are more stringent for vulnerable populations (US Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.) For example, minors must have the consent of a legal guardian in order to participate in research. In some cases, the minors themselves are also asked to participate in the consent process by signing special, age-appropriate consent forms or giving verbal assent. Vulnerable populations raise many unique concerns because they may not be able to fully consent to research participation. Researchers must be concerned with the potential for underrepresentation of vulnerable groups in studies. On one hand, researchers must ensure that their procedures to obtain consent are not coercive, as the informed consent process can be more rigorous for these groups. On the other hand, researchers must also work to ensure members of vulnerable populations are not excluded from participation simply because of their vulnerability or the complexity of obtaining their consent. While there is no easy solution to this double-edged sword, an awareness of the potential concerns associated with research on vulnerable populations is important for identifying whatever solution is most appropriate for a specific case.

Protection of Identities

As mentioned earlier, the informed consent process requires researchers to outline how they will protect the identities of subjects. This aspect of the process, however, is one of the most commonly misunderstood aspects of research.

In protecting subjects’ identities, researchers typically promise to maintain either the anonymity or confidentiality of their research subjects. Anonymity is the more stringent of the two. When a researcher promises anonymity to participants, not even the researcher is able to link participants’ data with their identities. Anonymity may be impossible for some social researchers to promise because of the several of the modes of data collection employed. Face-to-face interviewing means subjects will be visible to researchers and will hold a conversation, making anonymity impossible. In other cases, the researcher may have a signed consent form or obtain personal information on a survey and will therefore know the identities of their research participants. If the research will require two or more incidents of data collection (for example, a survey once a month for a year to see change over time), then to be able to link a respondent’s responses to themselves, something identifiable will almost certainly be required.

In the case that anonymity is impossible to achieve, a researcher should be able to at least promise confidentiality to participants. Offering confidentiality means that some of the subjects’ identifying information is known and may be kept, but only the researcher can link identity to data with the promise to keep this information private. Confidentiality in research and clinical practice are similar in that you know who your clients are but others do not, and you promise to keep their information and identity private. As you can see under the “Risks” section of the consent form shown above, sometimes it is not even possible to promise that a subject’s confidentiality will be maintained. This is the case if data collection takes place in public or in the presence of other research participants, like in a focus group study. Researchers also cannot promise confidentiality in cases where research participants pose an imminent danger to themselves or others, or if they disclose abuse of children or other vulnerable populations. These situations fall under an individuals duty to report (depending on their roles and the laws in their location), which requires the researcher to prioritize their legal obligations over participant confidentiality.

Protecting research participants’ identities is not always a simple prospect, especially for those conducting research on stigmatized groups or illegal behaviors. Sociologist Scott DeMuth learned how difficult this task was while conducting his dissertation research on a group of animal rights activists. As a participant observer, DeMuth knew the identities of his research subjects. When some of his research subjects vandalized facilities and removed animals from several research labs at the University of Iowa, a grand jury called on Mr. DeMuth to reveal the identities of the participants in the raid. When DeMuth refused to do so, he was jailed briefly and then charged with conspiracy to commit animal enterprise terrorism and cause damage to the animal enterprise (Jaschik, 2009).

Publicly, DeMuth’s case raised many of the same questions as Laud Humphreys’ work 40 years earlier. What do social scientists owe the public? By protecting his research subjects, is Mr. DeMuth harming those whose labs were vandalized? Is he harming the taxpayers who funded those labs, or is it more important that he emphasize the promise of confidentiality to his research participants? DeMuth’s case also sparked controversy among academics, some of whom thought that, as an academic himself, DeMuth should have been more sympathetic to the plight of the faculty and students who lost years of research as a result of the attack on their labs. Many others stood by DeMuth, arguing that the personal and academic freedom of scholars must be protected whether we support their research topics and subjects or not. DeMuth’s academic adviser even created a new group, Scholars for Academic Justice (http://sajumn.wordpress.com), to support DeMuth and other academics who face persecution or prosecution as a result of the research they conduct. What do you think? Should DeMuth have revealed the identities of his research subjects? Why or why not?

The informed consent allows the researchers to meet the principle of respect for persons. This principle requires that the autonomy of the participants must be respected. They must be able to make the decision to participate after being informed of the potential risks in a way they understand, and they must know they are allowed to leave a study at any time should they choose to do so.

Part of making sure that participants understand what they’re getting into is the language and format of the consent. Depending on who is being studied, an informed consent document may need to be written in a certain way or translated to participants’ native languages. Researchers may also need to read the consent documents to participants, and should always be available to answer questions about the document before someone signs it or begins participating in the research.

Incentives

Incentives help get participants into your study and can keep them motivated through dry research projects (there’s only so long one can select that they “strongly agree” to a list of statements). Incentives are a tricky part of research: you often can’t do low-benefit research without them unless it’s exceedingly low effort (someone might answer two questions at the end of a phone call without expecting payment, but who wants to take a 30-minute survey with no incentive or sit through an hour-long interview?), but they must be ethical in how they’re applied. Consider what you’re asking your participants to give up to take part in the research (for example, if they have to take time out of their workday or drive a distance to participate, can you compensate them for the time or gas?) as well as what might motivate them to stick around long enough to answer well (a meal voucher at the end of a short interview might get college students to answer the questions). What you want to avoid is an incentive that is so enticing that someone will participate in a study they don’t actually feel good about because they can’t turn it down (offering a parent in poverty a hundred dollars to answer some invasive questions, for example).

Deception

Is it ever ethical to lie to participants? What if it’s just a little white lie?

The answer may surprise you.

In most cases, we need to be completely transparent with research participants. They need to know exactly what they are doing and why. However, it can compromise the results of a study if participants begin to act in a certain way because they know that the researchers are expecting something of them (this is sometimes called the Hawthorne Effect). This is where the research needs can sometimes come into conflict with the ethical needs of participants. In this case, the IRB would need to be consulted to see exactly what they will allow, but in general, in cases where the entirety of the project cannot be outlined to participants ahead of participation (or true deception, like lying about the purpose of the study, is required), the informed consent should still include as much as possible (including any more-than-minimal risks to the participants) and then the researchers should have a plan in place for debriefing the participants, that is, telling them the truth, as soon as possible. If questioned directly by the participants, the researchers should still answer honestly.

Risk-Benefit Analysis

In addition to describing what the research entails and the participant’s right to leave a study or where to get more information, informed consent also needs to address the risks and benefits of the study (and in this case, an incentive is not a benefit). Remember, beneficence means that the risks are worth the potential good to come from the study; it doesn’t mean that no risks exist, just that they’ve been minimized as much as possible and are appropriate to the potential rewards to be gained. Justice means that all groups, and then participants, selected for inclusion in the study bear the possibility of risks and reward fairly.

Take a moment and think about what we mean by risks and benefits. Potential risks and benefits are often pretty obvious in something like medical or drug studies; the risks are often physical, and the benefits likely are too. Because we often think of those obvious risks and benefits, it can be hard to consider what risks or benefits might be apparent in a much less invasive study, such as a survey. Note here that we’re talking about risks and benefits to the participants themselves; what might harm them if they participate, and in what ways may they personally benefit? Occasionally, students confuse this analysis with thinking about things we call “threats to validity,” which are the potential events that could harm the study itself (like people dropping out). We’ll talk about those risks later.

What Do You Think?

There are two study ideas below. Pretend you are part of the IRB reviewing these studies and consider the risks and benefits inherent to each. Write down a list of the risks and benefits you see. Once you’ve done that list for both studies and exhausted what you think could be included, determine if you think the risks of each study are appropriate for the benefits. This is the question of beneficence in action.

After you’ve completed your analysis, look below for one person’s assessment. It might be helpful to compare your assessment to your classmates, too, for an even broader look at this issue!

Study 1: Online Commitment Study

Respondents will be recruited online from social media sites to answer questions, also online, about their perceptions of commitment between themselves and their long-term dating partners.

What risks do you see present in Study 1?

What benefits do you see present in Study 1 (if any)?

Study 2: Parental Reunification Intervention Trial

Respondents are recruited from the intake of a social services office to participate in a randomized experiment. Parents who have had their child(ren) removed due to abuse or neglect allegations are eligible to participate. They may be given either an 8-week parenting workshop or 6 one-on-one sessions with a family coach, depending on the random assignment, then they will be assessed for suitability to receive their child(ren).

What risks do you see present in Study 2?

What benefits do you see present in Study 2 (if any)?

Study 1 – Some Considerations

Some studies seem so benign that it’s hard to identify risks. Study 1 may have felt that way for you. Participating in an online survey from the comfort of your home still carries risks, though!

For one, there’s always a risk of a data breach; researchers can and should do their very best to protect their participants’ data, but we should always warn participants of the risk. We can mitigate that through careful practices (password-protected computers, encrypted collection programs, locked file cabinets and offices, and removing identifying information as soon as possible), but it’s still a risk. Similarly, a participant being identified is sometimes a risk worth mentioning too; if you’re studying something potentially embarrassing or socially damaging, being careful to uphold confidentiality (or better yet, anonymity if you can) is very important.

There’s also risks of emotional distress from considering a research topic, or even, in special cases like in the study described here, risks to providing honest answers if others in the household or family might see the answers and be angered or the relationship damaged. We want honest answers, but we also need to recognize that some people won’t be honest if they’re fearful for their relationship or own safety.

How about benefits to Study 1? There actually may not be any, at least not to the participant themselves. You may be asking yourself “how can a study promise no benefits?” It’s a good question; studies with few or no benefits often have to be either extremely easy to complete (with extremely low risk) or have a motivating incentive. For the IRB to even approve a study like this they need to believe that their are benefits to society from the potential information to be gained; we should never do a study “just because.” To understand the potential benefits to society, and to explain these benefits, a strong literature review is necessary.

Study 2

What about Study 2? This study’s risks and benefits are more obvious that Study 1. In Study 2, there’s a risk that participants may not receive the branch of treatment most effective for them (it’s a randomized trial), and there’s also a risk that if an educator or coach sees evidence that the parent is a danger to the child they would have to report it. The benefit, though, is potentially great: parents may improve in their parenting abilities and readiness to receive their children (in fact, that’s the goal) from participating in the program and the study.

It’s important to consider both risks and benefits to studies. Remember that beneficence doesn’t mean that there are no risks, and not every study is required to have tangible benefits. Rather, there needs to be an appropriate balance between risks and benefits for each participant, and the participants should stand to receive both fairly (that’s justice).

References

- Jaschik, S. (2009, December 4). Protecting his sources. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from: http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/12/04/demuth ↵

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2009). Code of federal regulations (45 CFR 46). The full set of requirements for informed consent can be read at https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html ↵

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Recommendations for vulnerable populations. Office for Human Research Protections. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp-committee/recommendations/recommendations-for-vulnerable-populations/index.html

Image Attributions

- consent by Catkin CC-0

- Anonymous by kalhh CC-0

- Informed consent form: focus groups figure copied from Blackstone, A. (2012) Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods. Saylor Foundation. Retrieved from: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_principles-of-sociological-inquiry-qualitative-and-quantitative-methods/ Shared under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/) ↵