What Is a Literature Review?

Reading research is important because it allows you to understand what has been explored regarding your topic before. It allows you to see how the major voices are, what questions have been asked and answered, how things have been defined, and what questions remain. Once you’ve done all that reading, your next step is to communicate what you’ve learned and use that to argue for the importance of the research question you want to answer. To do this, you need to write a literature review.

Pick up nearly any book on research methods and you will find a description of a literature review. At a basic level, the term implies a survey of factual or nonfiction books, articles, and other documents published on a particular subject. Definitions may be similar across the disciplines, with new types and definitions continuing to emerge. Generally speaking, a literature review is a:

- “comprehensive background of the literature within the interested topic area” (O’Gorman & MacIntosh, 2015, p. 31).

- “critical component of the research process that provides an in-depth analysis of recently published research findings in specifically identified areas of interest” (Houser, 2018, p. 109).

- “written document that presents a logically argued case founded on a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge about a topic of study” (Machi & McEvoy, 2012, p. 4).

Literature reviews are indispensable for academic research. “A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research…A researcher cannot perform significant research without first understanding the literature in the field” (Boote & Beile, 2005, p. 3). In the literature review, a researcher shows she is familiar with a body of knowledge and thereby establishes her credibility with a reader. The literature review shows how previous research is linked to the author’s project by summarizing and synthesizing what is known while identifying gaps in the knowledge base, facilitating theory development, closing areas where enough research already exists, and uncovering areas where more research is needed. (Webster & Watson, 2002, p. xiii). Literature reviews are often necessary for real world applications of social research. Grant proposals, advocacy briefs, and evidence-based practice rely on a review of the literature to accomplish goals.

You’ve probably written an assignment called a literature review before. Unfortunately, when it comes to research, “literature review” is actually a pretty bad name for this important text. The name “literature review” tends to conjure a list of papers that writers feel they must describe one by one in a never-ending list: “So-and-so from Fancy University found this finding, and then such-and-such from Other College found…”

That’s. So. Boring.

There really is a better way. We can make the case for our questions in, if not necessarily “interesting,” at least a compelling way. We can write what could be thought of as a “narrative review” to make the case for the novelty and importance of our question through telling a story of what we know, what we don’t know, and why it’s important that we know it. This is really meant to be more of a persuasive essay that guides the reader through a brief history of what’s known in the area of interest before convincing them that the new question of the current study is novel and important, rather than just a list of all the papers that have been done by themselves. Unlike an annotated bibliography or a research paper you may have written in other classes, your literature review will outline, evaluate, and synthesize relevant research and relate those sources to your own research question. It is much more than a summary of all the related literature. A good literature review lays the solidifies the importance of the problem your study aims to address, defines the main ideas of your research question, and demonstrates their interrelationships.

Literature review basics

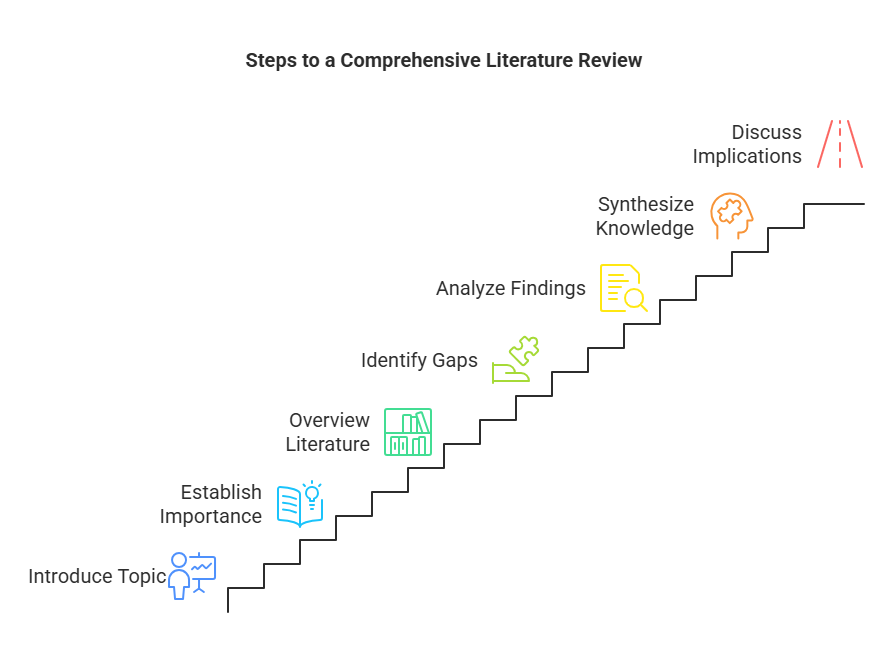

All literature reviews, whether they focus on qualitative or quantitative research, will at some point:

- Introduce the topic and define its key terms.

- Establish the importance of the topic.

- Provide an overview of the important literature on the concepts in the research question and other related concepts.

- Identify gaps in the literature or controversies.

- Point out consistent and inconsistent finding across studies.

- Arrive at a synthesis that organizes what is known (and unknown) about a topic, rather than just summarizing.

- Discuss possible implications and directions for future research.

Let’s Break it Down?

Show

Steps to a Strong Literature Review

*This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

-

Introduce the topic and define its key terms

Briefly explain what your research is about, and clearly define important terms so the reader understands the focus, scope, and relevance of your study. Be especially mindful of conceptually defining your variables of interest—that is, providing clear explanations of what each variable means within the context of your research. This helps avoid confusion and ensures consistency throughout your study. Additionally, provide a concise statement of your research question or hypothesis to clarify the direction and purpose of your work. This allows the reader to understand how your study builds on or addresses gaps in the existing literature. -

Establish the importance of the topic

Explain why the topic matters—highlight its relevance to society, a field of study, or a specific problem.

Showing its significance engages the reader and justifies why your research question is worth exploring. -

Provide an overview of the important literature on the concepts in the research question and other related concepts

Summarize major studies and theories that have shaped current understanding of your topic and related ideas.

This builds context and shows that you understand the foundation of your research area. -

Identify gaps in the literature or controversies

Point out what is missing, under-researched, or debated among scholars to show where your research fits in.

Identifying these gaps gives your study purpose and shows it contributes something new. -

Point out consistent and inconsistent findings across studies

Highlight areas where studies agree or disagree, helping to reveal patterns or contradictions in the field.

This critical analysis shows that you are not just summarizing but evaluating the literature. -

Arrive at a synthesis that organizes what is known (and unknown) about a topic, rather than just summarizing

Combine findings into a coherent narrative that shows how different pieces of research relate and build on each other.

A strong synthesis tells a story of the research landscape and highlights your analytical thinking. -

Discuss possible implications and directions for future research

Suggest how the findings can be applied or what future researchers should explore based on what’s currently known and unknown.

This final step shows that you’re thinking forward and contributes to the ongoing scholarly conversation.

Dr. Christie Knight

There are many different types of literature reviews, including those that focus solely on methodology, those that are more conceptual, and those that are more exploratory. Regardless of the type of literature review or how many sources it contains, strong literature reviews have similar characteristics. Your literature review is, at its most fundamental level, an original work based on an extensive critical examination and synthesis of the relevant literature on a topic. It is arranged by key themes or findings, which should lead up to or link to the research question.

A literature review is a mandatory part of any research project. It demonstrates that you can systematically explore the research in your topic area, read and analyze the literature on the topic, use it to inform your own work, and gather enough knowledge about the topic to conduct a research project. Literature reviews should be reasonably complete, and not restricted to a few journals, a few years, or a specific methodology or research design. A well-conducted literature review should indicate to you whether your initial research questions have already been addressed in the literature, whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of findings of the literature review. The review can also provide potential answers to your research question, help identify theories that have previously been used to address similar questions, as well as provide evidence to inform policy or decision-making (Bhattacherjee, 2012).

In addition, literature reviews are beneficial to you both as a researcher and as a future professional in the field. By reading what others have argued and found in their work, you become familiar with how people talk about and understand your topic. During the process, you will refine your writing skills and your understanding of the topic you have chosen. The literature review also impacts the question you want to answer. As you learn more about your topic, you will clarify and redefine the research question guiding your inquiry. By completing a literature review, you ensure that you are neither repeating a study that has been done numerous times in the past, not repeating mistakes of past researchers. The contribution your research study will have depends on what others have found before you. Try to place the study you wish to do in the context of previous research and ask, “Is this contributing something new?” and “Am I addressing a gap in knowledge or controversy in the literature?” Remember how we talked about a dinner party conversation back when we first discussed research questions? This is where you get the chance to summarize what you’ve “heard” (read) and how that relates to what you’re about to say, which is your research idea.

In summary, you should conduct a literature review to:

- Locate gaps in the literature of your discipline

- Avoid “reinventing the wheel,” by repeating past studies or mistakes

- Carry on the unfinished work of other scholars

- Identify other people working in the same field

- Increase the breadth and depth of knowledge in your subject area

- Read the key works in your field

- Provide intellectual context for your own work

- Acknowledge opposing viewpoints

- Put your work in perspective

- Demonstrate you can find and understand previous work in the area

You’ve hopefully already started searching and reading literature on your topic; as you continue to read and develop your research question, also be developing the argument for why your question is novel and important – that will be the core of your literature review.

Synthesizing the literature

To write an effective literature review, you need to know what you’ve read and have organized the ideas in a way that makes sense to you. There are a lot of ways to organize the information you find as you read. If you already have a good method, then please feel free to continue using that. If you’re new to this process, experiment with ways of taking notes and organizing information. Basically, you need a way to record what is in each source and consider how each source relates to the others and to your ideas.

You will be working to create a synthesis of the literature. This is what separates a true literature review from a list. A synthesis demonstrates a critical analysis of the papers as well as an integration of their results. Each source you collect should be critically evaluated using the methods discussed earlier, then you should record your notes on the source, paying attention to details like specific findings as well as how they got those findings.

Let’s Break it Down

Show

Synthesis of Literature

* This image was created using ChatGPT; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

A strong literature review doesn’t just list one study after another. That kind of review simply summarizes each source separately. Instead, a well-written review synthesizes the research—it connects ideas and tells a story about what we know (and don’t know) about the topic.

In a synthesis, you won’t see a lot of direct quotes. Instead, you’ll see the writer combine findings from different studies, pointing out patterns, agreements, or disagreements across the research. They might cite several sources at once to show that many researchers found similar results, or compare studies to highlight differences in methods or conclusions.

Dr. Christie Knight

Begin the synthesis process by creating a grid, table, or an outline where you will summarize your literature review findings, using common themes you have identified and the sources you have found. The summary, grid, or outline will help you compare and contrast the themes, so you can see the relationships among them as well as areas where you may need to do more searching. Whichever method you choose, this type of organization will help you to both understand the information you find and structure the writing of your review. If one exact model doesn’t work for you, find one that does! Writing this out by hand on a whiteboard may be helpful so that you can draw arrows between findings. Writing your sources on sticky notes might be useful so you can organize and re-organize them according to different characteristics. Using a computer program to create a grid may work well for you. Find what works with your brain!

As you read through the material you gather, look for common themes as they may provide the structure for your literature review. Also look for holes – what information are you missing to be able to make some connections? What questions come up as you look at the themes emerging? Remember, it is not unusual to go back and search academic databases for more sources of information as you read the articles you’ve already collected.

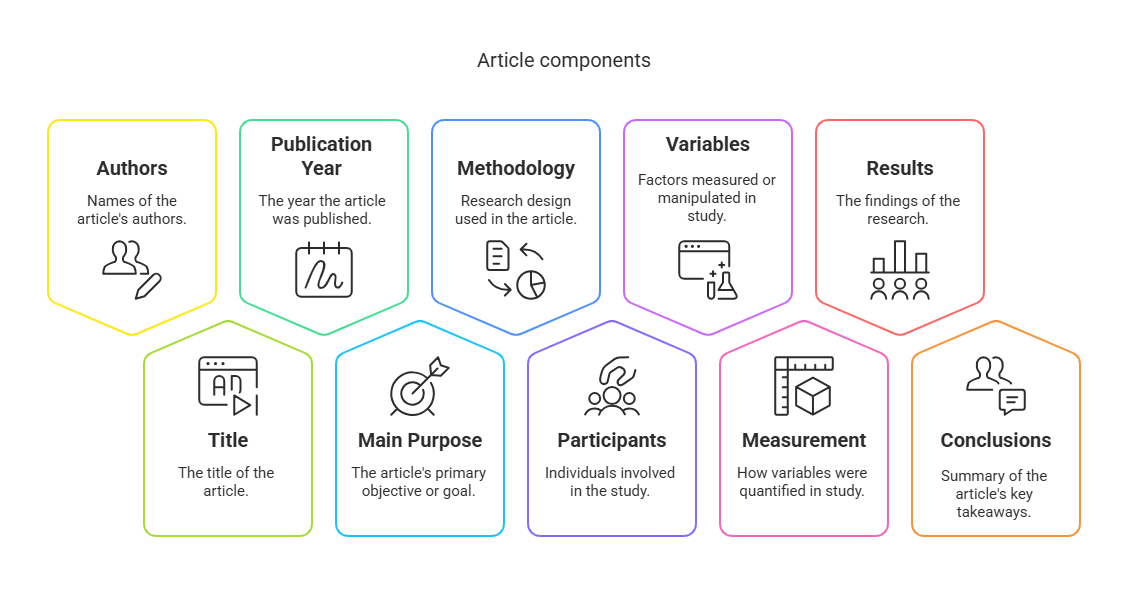

However you do it, take detailed notes on each article and use a consistent format for capturing all the information each article provides. Examples of fields you may want to capture in your notes include:

- Authors’ names

- Article title

- Publication year

- Main purpose of the article

- Methodology or research design

- Participants

- Variables

- Measurement

- Results

- Conclusions

*This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

Other fields that will be useful when you begin to synthesize the sum of your research include:

- Specific details of the article or research that are especially relevant to your study

- Key terms and definitions

- Statistics

- Strengths or weaknesses in research design

- Relationships to other studies

- Possible gaps in the research or literature (for example, many research articles conclude with the statement “more research is needed in this area”)

- Finally, note how closely each article relates to your topic. You may want to rank these as high, medium, or low relevance. For papers that you decide not to include, you may want to note your reasoning for exclusion, such as small sample size, local case study, or lacks evidence to support conclusions.

*This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

Planning Your Literature Review

Literature reviews can be organized sequentially or by topic, theme, method, results, theory, or argument. It’s important to develop categories that are meaningful and relevant to your research question as you analyze the papers you’ve read. After you have collected the articles you intend to use (and have put aside the ones you won’t be using), it’s time to extract as much as possible from the facts provided in those articles. You are starting your research project without a lot of hard facts on the topics you want to study, and by using the literature reviews provided in academic journal articles, you can gain a lot of knowledge about a topic in a short period of time.

When making your notes documents, you should copy and paste any fact or argument you consider important, such as definitions of concepts, statistics about the size of the social problem, and empirical evidence about the key variables in the research question, among countless others. Facts for your literature review are principally found in the introduction, results, and discussion section of an empirical article or at any point in a non-empirical article. Again, any information you may want to use in your literature review should go into your notes document. During this process, it is imperative that you cite the original article or source that the information came from. This way, you will not make the mistake of plagiarizing when you use these notes to write your research paper and you will be able to refer to the article with ease. Nothing is worse than pulling facts from your notes, only to realize that you forgot to note where those facts came from. In addition, if you found a statistic that the author used in the introduction, it almost certainly came from another source that the author cited in a footnote or internal citation. You will want to check the original source to make sure the author represented the information correctly as well as cite the original, primary source of that statistic. Moreover, you may want to read the original study to learn more about your topic and discover other sources relevant to your inquiry.

Assuming you have pulled all of the facts out of multiple articles, it’s time to start thinking about how these pieces of information relate to each other. Start grouping each fact into categories and subcategories. For each topic or subtopic you identified during your critical analysis of each paper, determine what those papers have in common. Likewise, determine which ones in the group differ. If there are contradictory findings, you may be able to identify methodological or theoretical differences that could account for the contradiction. For example, one study may sample only high-income earners or those in a rural area. Determine what general conclusions you can report about the topic or subtopic, based on all of the information you’ve found.

This is a good time to start a separate document containing a topical outline to combine your facts from each source and organize them by topic or category. As you include more facts and more sources into your topical outline, you will begin to see how each fact fits into a category and how categories are related to each other. Your category names may change over time, as may their definitions. This is a natural reflection of the learning you are doing. A complete topical outline is a long list of facts, arranged by category about your topic. As you step back from the outline, you should be able to identify the topic areas in which you have gathered sufficient information to draw strong conclusions. You should also be able to identify areas in which you will need to conduct further research to gain a better understanding of the topic. The topical outline should serve as a transitional document between the notes you write on each source and the literature review you submit in your class.

At this point, it is important to note that both the notes documents and the topical outline contain plagiarized information that is copied and pasted directly from the primary sources. Don’t worry just yet thought – these are just notes that are meant to guide you and are not being turned in to your professor as your own ideas. To avoid any possibility of plagiarism in your actual literature review, you must paraphrase each piece of information or synthesize it with others and properly attribute it to its primary source. More importantly, you should keep your voice and ideas front-and-center in what you write as this is your analysis of the literature. Make strong claims and support them thoroughly using facts you found in the literature. For now, though, you’re just organizing what you’ve found so far and making connections based on what you’ve learned.

References

Boote, D., & Beile, P. (2005). Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educational Researcher, 34(6), 3-15.

Bhattacherjee, A., (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices. Textbooks Collection. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/oa_textbooks/3

Houser, J., (2018). Nursing research reading, using, and creating evidence (4th ed.). Jones & Bartlett.

Machi, L., & McEvoy, B. (2012). The literature review: Six steps to success (2nd ed). Corwin.

O’Gorman, K., & MacIntosh, R. (2015). Research methods for business & management: A guide to writing your dissertation (2nd ed.). Goodfellow Publishers.

Webster, J., & Watson, R. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly, 26(2), xiii-xxiii. https://web.njit.edu/~egan/Writing_A_Literature_Review.pdf